Abstract

Purpose

To test whether CD4+ T cells proliferate in mixed cell reactions with autologous lacrimal gland acinar cells and whether these cells can autoadoptively transfer disease.

Methods

Purified acinar cells were gamma-irradiated and co-cultured with peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL). Activated CD4+ T cells were sorted by FACS and unfractionated activated PBL (UF) from an autologous mixed cell reaction (AMCR), CD4+ enriched and CD4+ depleted T cells were injected into the donor rabbit’s remaining lacrimal gland (LG). After 4 weeks ocular examinations were performed and the rabbits were euthanized; LG were removed for histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and real time RT-PCR studies.

Results

CD4+ T cells increased in the AMCR from 20% to 80%. Tear production decreased in the induced disease/UF (ID/UF) group and declined even more in the ID/CD4+ enriched group. Tear breakup times decreased and rose bengal staining increased in all groups. All LG exhibited significant histopathology and increased mRNAs for TNF-α. The ID/UF group exhibited the largest increases of CD4+ and RTLA+ cells. The ID/CD4+ enriched group contained fewer infiltrating CD4+ cells, but more eosinophils, severely altered acinar morphology, and increased fibrosis. LG of the ID/CD4+ depleted group exhibited large increases of CD18+, MHC II+ and CD4+ cells. mRNAs for IL-2, IL-4, and CD4 increased in the ID/CD4+enriched group compared to the CD4+depleted group.

Conclusions

Autoreactive CD4+ effector cells activated ex vivo and autoadoptively transferred, caused what appears to be a distinct dacryoadenitis. The CD4+depleted cell fraction also contained pathogenic effector cells capable of inducing disease.

Keywords: Dry eye, Sjögren’s syndrome, lacrimal gland, CD4+ T lymphocytes

Background

Antigen specific CD4+ T cells play major roles in a variety of autoimmune diseases. In mouse models for the progressive autoimmune disease of rheumatoid arthritis, transfer and depletion of CD4+ T cells and the use of TCR-transgenic (TCR-Tg) animals showed that joint antigen-specific CD4+ T cells with a Th1-like phenotype mediate the induction or aggravation of joint inflammation (1–3). Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the lacrimal gland (LG) associated with severe dry eye disease and, frequently, visual impairment. The infiltrates in Sjögren’s syndrome are focally organized in the periductal and perivascular stroma and consist mainly of CD4+ T cells and B cells (4, 5). The infiltrates produce IgG antibodies against epithelial autoantigens and a combination of Th1 and Th2 cytokines that mediate a cascade of cellular responses. These infiltrates have been reported to produce cytotoxic factors (6) and mediators that induce viable parenchymal cells to become functionally quiescent.

Patients with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) frequently present with dry eye symptoms and with lacrimal gland immunohistopathology consistent with an autoantibody and CD4+ T cell-mediated process. However, these symptoms are typically more severe than those of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, and the lacrimal immunohistopathology considerably more robust.

Most cases of dry eye disease, however, appear to be associated with a dacryoadenitis that occurs independently of autoantibody-positive autoimmune disease (7–11). It is likely that CD4+ T cells also participate in this pathophysiological process. Very large numbers of MHC II expressing immune cells and parenchymal cells are frequently present in cadaver lacrimal glands (12). Even less is known about the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of the more prevalent disease than about Sjögren’s syndrome (13–15). The phenotypes of the cells that infiltrate affected biopsy and postmortem lacrimal glands have not been characterized. Animal models of age-related lacrimal gland immunopathologies appear to present a mast-cell mediated process that does not necessarily recapitulate the process which occurs in humans(16, 17). Because Sjögren’s dacryoadenitis is characterized by the formation of ectopic lymphoid tissues organized for production of IgG autoantibodies, while the more common histopathological syndrome is not, it is possible that the pathophysiological mechanisms of the two diseases differ in important respects. If so, it may be possible to design specific therapies for each disease.

When isolated and placed in primary culture, acinar cells from rabbit LGs appear to take on functions of antigen presenting cells. Rabbit acinar cells grown in vitro express MHC II molecules and stimulate autologous PBLs to proliferate when they are co-cultured (i.e. autologous mixed cell reactions, aka AMCR). Lymphocyte proliferation in this model depends on direct contact between PBL and acinar cells, and it is inhibited by antibodies to rabbit MHC Class II (18). The cells activated in such AMCRs include pathogenic effector cells, which induce (i.e., autoadoptive transfer) a robust dacryoadenitis when returned to the original donor animal. The lesions in the LG resemble those of Sjögren’s syndrome in that they are focally organized around interlobular ducts and venules. Lesions contain CD4+ T cells in a fourfold excess over CD8+ cells. The CD4+ T cells are thought to be associated with both decreased exocrine function, as assessed by decreased Schirmer scores, increased ocular surface pathology, decreased tear breakup times (BUT), and increased rose bengal staining (19–21).

The present study was undertaken to test the hypotheses that CD4+ T cells are the major lymphocyte population that proliferate in AMCR and that CD4+ lymphocytes purified from these AMCR are capable of autoadoptively transferring disease independently of other cells present in the mixed cell reaction. While the findings described below validated these hypotheses, they unexpectedly also revealed that the CD4+ depleted lymphocyte population also was pathogenic and, moreover, that each sample of activated lymphocytes, i.e., unfractionated, CD4+ enriched, and CD4+ depleted, induced a distinct combination of immunopathological manifestations in the ocular surface tissues and lacrimal glands. For this manuscript we selected representative T cell markers and Th1, Th2, regulatory and innate rabbit cytokines which had known primer and probe sequences for our real time RT-PCR mRNA studies. By monitoring these various parameters in lacrimal glands mRNA from normal and animals with distinctively different dacryoadenitides provided us with an opportunity to identify possible relationships of various cytokines and cell markers with the different induced diseases.

Methods

Animals, Reagents, and Ocular Assessments

Female New Zealand white rabbits, each weighing between 3.4 and 4 kg, were obtained from Irish Farms (Norco, CA). The animals were maintained and used in compliance with institutional guidelines and in accord with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Clinical examinations were performed on all eyes before any experimental procedures to establish baseline data and to exclude any animals with ocular defects. All eyes were reassessed after 4 weeks for tear production (Schirmer test), tear stability (tear breakup time, BUT) and surface defects (rose bengal staining). Schirmer tests were performed without anesthesia on both eyes of all animals. After instillation of fluorescein, BUT was evaluated by examination with a slit-lamp biomicroscope equipped with a blue filter. Rose bengal staining was scored with a standardized grading system (21). Schirmer strip paper was purchased from Rose Stone Enterprises (Alta Loma, CA). FUL-GLO fluorescein strips and rose bengal strips were purchased from Akorn Inc. Laboratories (Buffalo Grove, IL). Monoclonal antibodies specific for rabbit T cells (formerly CD5, a general T cell marker), CD4, CD8, and CD18 and MHC II were purchased from Antigenix America (Huntington Station, NY), and antibodies specific for RTLA (rabbit T lymphocyte antigen) were obtained from Cedarlane Laboratories (Hornby, Ontario, Canada). Species-specific secondary antibodies were obtained from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). ABC reagent and AEC were obtained from Vector Laboratories, Inc. (Burlingame, CA).

Autologous Mixed Cell Reaction and Induction of Disease

Descriptions of lacrimal gland excision, acinar cell purification, mixed cell reaction, and induction of autoimmune dacryoadenitis procedures have been previously published (18, 22). Briefly, acinar cells and PBL were isolated and cultured separately for 2 days. Mixed cell reactions were performed in 12-well plates, using an equal number (1×106 cells/mL) of autologous PBL and γ-irradiated pLGEC (2500 RAD), then co-cultured for 5 days. Mixed cell reactions also were performed in 96-well plates under the same conditions, but using 1×105 cells of each type, to monitor PBL proliferation. [3H]-thymidine was added after 4 days of co-culture, and cells were harvested 24 hours later using a Brandel model 290 PHD™ sample harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD). An LS 6000IC beta scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, CA) was used to measure [3H]-thymidine incorporation. A minimum of 6 wells were counted to obtain representative data for each animal. Lymphocytes from mixed cell reactions with stimulation indices greater than 2 were considered to be activated. Cell surface staining was done with PBLs before and after mixed cell reaction with mAB specific for rabbit T cell, B cell, CD4 and CD8 (Antigenix America) antibodies and analyzed by FACS. Activated lymphocytes from the parallel 12-well plates were labeled with PE-conjugated anti-rabbit CD4 antibody, and FACS was used to separate CD4+ enriched and CD4+ depleted cell preparations. Sorted cells are estimated to have >98% purity. In one experiment, the CD4+ enriched lymphocytes were injected directly into the remaining lacrimal glands of their original donor animals (Induced Disease/CD4+ enriched group, hereafter referred as ID/CD4+ enriched; n=9). In another experiment, CD4+ depleted cell preparations were injected into the remaining lacrimal glands of the original donor animals (i.e. ID/CD4+ depleted group, n=6). In a third experiment, 1×106 unfractionated activated lymphocytes from AMCRs were injected directly into the remaining lacrimal glands (ID/UF group, n=6). All results were compared to a normal control group of rabbits (n=6). Rabbits were sacrificed 4 weeks after injection of lymphocytes. The injected LGs were removed and divided into portions for paraffin-embedding, cryosectioning, and extraction of mRNA.

Histopathology and Immunocytochemistry

Lacrimal gland tissues fixed in 10% formalin were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histology. Some of the tissue was embedded in OCT and cryosectioned at 7 µm for immunostaining as described previously (23). Briefly, sections were fixed in chilled acetone, air dried, and rehydrated in phosphate-buffered saline. Sections were blocked in 5% Bovine serum albumin for 15 minutes then incubated at room temperature for 1 hr with the primary antibody diluted as follows: mouse anti-rabbit CD4 (1:200), mouse anti-rabbit CD8 (1:200), mouse anti-rabbit CD18 (1:1000), goat anti-rabbit RTLA (1:300) and mouse anti-rabbit MHC II (1:100). Sections were rinsed and incubated for 60 minutes with appropriate secondary antibodies. After rinsing, sections were quenched in 0.3% H2O2 in 40% methanol for 15 minutes and incubated in ABC reagent for 30 minutes, rinsed three times, and developed with AEC. Sections were again rinsed, counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted for microscopic examination. The positive cells showed an intense brown color in the blue hematoxylin background. Entire sections were scanned and analyzed with Analysis 3.0 (Olympus Soft Imaging System Lake Wood, CO), an automated cellular imaging system. This combination of a proprietary, color-based imaging technology with an automated microscope provides quantitative data, including percent positive with intensity scoring and area measurement.

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Primers and probes were selected using Primer Express™ software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and synthesized by Applied Biosystems (Table 1). All probes incorporated the 5′ reporter dye 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) and the 3′ quencher dye 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was performed with an ABI PRISM® 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan universal PCR master mix containing the internal dye ROX, as a passive reference. The PCR reaction volume of 10 µl contained 1×TaqMan universal PCR master mix, 300 nM forward and reverse primers, 250 nM probe, and 1 µL of cDNA template. The FAM signal was measured against the ROX signal to normalize for non-PCR-related fluorescence fluctuations. The cycle threshold (CT) value represented the refraction cycle number at which a positive amplification reaction was measured and set at 10 times the standard deviation of the mean baseline emission calculated for PCR cycles 3–15. CT for the housekeeping gene, GAPDH, was determined as an internal control in each sample. The GAPDH mRNA levels in all samples were similar, confirming that starting concentrations of cDNA were similar. The abundance of each target mRNA in each individual sample was expressed relative to the abundance of mRNA in that sample. Differences in the amount of input material were corrected for by using the difference between the target mRNA CT and the GAPDH CT to calculate the relative abundance of the target mRNA (24).

Table 1.

Rabbit Specific Primer and Probe Sequences for Real Time RT-PCR

| Target | Sequences | Accession # | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fwd→ | 5'-TCAACCCTGTGGCCCAGAT-3' | ||||

| TNFα | Rev | ← 5'-CGTGGGCTAGAGGCTTGTCA-3' | M12845 | ||

| Probe | 5'-ACCCTCAGATCAGCTTCTCGGGCC-3' | ||||

| Fwd | 5'-GGCTCAGGTCCTTGAAGTCTCA-3' | ||||

| CD4 | Rev | 5'-GCAGGCACTGGAAGTAGATTCTC-3' | M92840 | ||

| Probe | 5'-CGCCTCAGCAAAGCCACCATGAA-3' | ||||

| Fwd | 5'-GCAAGGACAGTGACCTCGAGTT-3 | ||||

| CD8 | Rev | 5'-CCCCCATGCCAAGTGTAGTC-3' | L22293 | ||

| Probe | 5'-CTGGCCTCATGGCATCCCGAGAA-3' | ||||

| Fwd | 5'-TCCAGACGAGGGCATCCA-3' | ||||

| IL-1β | Rev | 5'-CTGCCGGAAGCTCTTGTTG-3' | D21835 | ||

| Probe | 5'-CTGCGCATCTCCTGCCAACCCT-3' | ||||

| Fwd | 5'-TCTTGTCTTGCATTGCACTAACTCT-3' | ||||

| IL-2 | Rev | 5'-GATCCAGTTGTTCCTGTGTTTCC-3' | AF068057 | ||

| Probe | 5'-TCCTTACAAGCAGTGCACCTACTTCAAGTTCTACA-3' | ||||

| Fwd | 5'-CGACATCATCCTACCCGAAGTC-3' | ||||

| IL-4 | Rev | 5'-CAGCTTGGTGCATGGAGTCTT-3' | AF169169 | ||

| Probe | 5'-TCAAAACCCTGAACATCCTCACAGAGA-3' | ||||

| Fwd | 5'-TTGTCGGAGATGATCCAGTTTTAC-3' | ||||

| IL-10 | Rev | 5'-TGGCTGGACTGTGGTTCTCA-3' | AF068058 | ||

| Probe | 5'-TGAAGGACGTGATGCCGCAAG-3' | ||||

Statistical Analysis

Data collected from clinical analysis and Olympus Soft Imaging System were subjected to paired t test or signed rank sum test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inst, Cary, NC). mRNA abundance data were subjected to ANOVA and rank sum tests using Sigmaplot 11 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

FACS Analysis

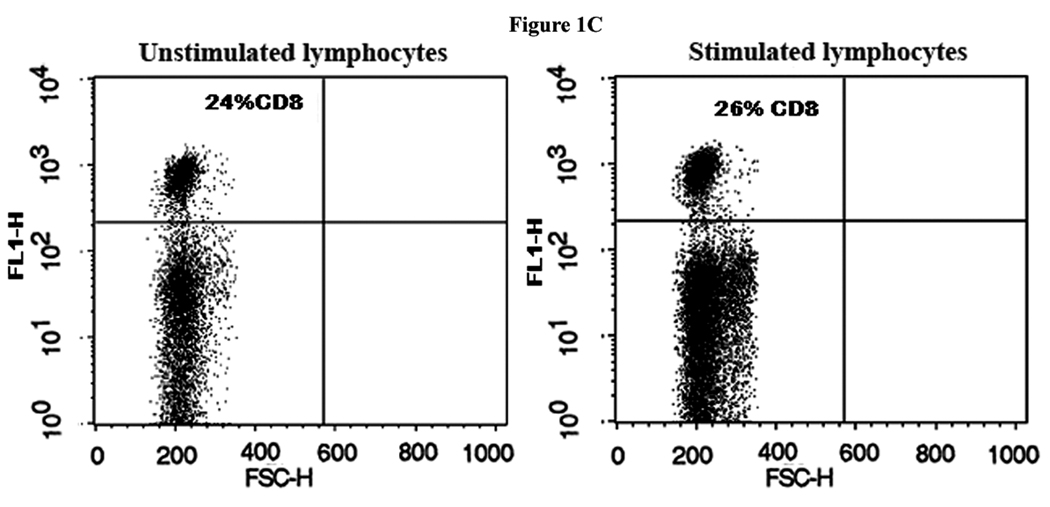

FACS analysis revealed that the T cell population increased approximately twofold in the mixed cell reaction when compared to the unstimulated lymphocytes (Fig. 1A).There was some variability in total number of T cells in different rabbits before and after stimulation. CD4+ T cells constituted 20% of the total T cells counted in PBL samples before activation in the mixed cell reactions and 80% after activation (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the proportion of CD8+ T cells did not change in the mixed cell reaction (Fig. 1C), whereas the B cell population either decreased or remained the same after stimulation in the mixed cell reaction (data not shown).

Figure 1. Marked expansion of CD4+ T cells in autologous mixed cell reaction (AMCR).

(A) Mononuclear cells were stained with an anti-T cell PE- labeled antibody before (unstimulated) and after (stimulated) culture in an AMCR. (B) Same as for (A) except the cells were stained with an anti-CD4 PE-labeled antibody. (C) Same as for (A) except the cells were stained with an anti-CD8 FITC-labeled antibody.

Tear Production

As has been reported previously (21), tear production in the OS eye returns to normal within 4 weeks after surgical removal of the inferior lacrimal gland, while injection of lymphocytes that had been activated in AMCR decreases tear production bilaterally. As shown in Fig. 2A, OD tear production decreased twice as much in the ID/CD4+ enriched group as in the ID/UF group. In contrast, OS tear production decreased to the same extent in the ID/CD4+ enriched group as the ID/UF group. The OD and OS tear production in the ID/CD4+ depleted group varied more among individual animals. While values were decreased in some animals, the mean values were not significantly different from the normal group.

Figure 2. Clinical Ocular Parameters.

A comparison of basal tear production, tear break-up time and rose bengal staining for both the OD (injected LG) and OS (excised inferior LG) eyes challenged with ID, ID/CD4+-enriched or ID/CD4+- depleted cell preparations is presented 30 days post-injection. The procedure for these clinical examinations was described previously (21). Each group consisted of at least six animals and one group was normal animals. (A). Compared to the normal group basal tear production for the OD eyes of the ID/UF group was reduced by an average of 35%, the ID/CD4+-enriched group by 71%, and the ID/CD4+depleted group by 12%. Compared to normal tear production, the ID/UF group’s OS eyes declined by 26%, the ID/CD4+- enriched group by 35%, and the ID/CD4+depleted group by 6%. (B). Compared to the tear break-up time of normal animals, the OD eyes of ID/UF group declined by 46%, ID/CD4+-enriched by 66%, and the ID/CD4+-depleted group by 54%. Values for the OS eyes of the ID/UF group declined by 48%, ID/CD4+-enriched group by 64%, and the ID/CD4+depleted group by 67%. (C). OD rose bengal scores for the ID/UF group increased by 5.5 fold, ID/CD4+enriched group by 6.1 fold, and the ID/CD4+depleted group by 3.7 fold. The OS rose bengal scores increased five- to sixfold.

Tear Break-up Time

The tear BUT of both OD and OS values decreased markedly from normal levels in all three groups (Fig. 2B). However, the values for the ID/CD4+ enriched group decreased significantly more than the values for the ID/UF group, both in OD eyes, where the Schirmer scores were also decreased more severely, and in OS eyes, where the Schirmer scores were decreased to the same extent as in the ID/UF group. In notable contrast to the absence of significant changes in tear production, tear BUT for both OD and OS decreased in the ID/CD4+ depleted group; the OD scores decreased to a mean value that did not differ significantly from the values for either the ID/UF group or the ID/CD4+ enriched group; the OS scores decreased to the same extent as the values of both eyes for the ID/CD4+ enriched group.

Rose Bengal Staining

The rose bengal staining scores increased to similar levels in all ID groups; scores for OD and OS were not significantly different in any of the three groups (Fig. 2C).

Histopathology

The H&E stained paraffin sections were examined in a double blind fashion. Lacrimal glands from normal animals displayed occasional small aggregates of infiltrating immune cells. Lacrimal glands of the ID/UF group were infiltrated with immune cells that were frequently concentrated around ducts and venules as well as numerous plasma cells, (Fig. 3A). Some LG lobules contained degenerating acini, while other lobules in the same gland appeared normal.

Figure 3. Histopathology with H&E.

(A) Normal LG showed acinar cells (ac) with pale apical cytoplasm due to accumulated secretory vesicles and nuclei at the basal side of the cells; d represents ducts. (B) Section from an ID/UF group lacrimal gland 4 weeks post-injection contained large lymphocytic foci (black arrows) around venules and within the connective tissue around ducts. (C) Rabbits injected with CD4+ enriched preparations (ID/ CD4+ enriched) had multiple large foci of lymphocytic infiltrates (black arrows), morphologically altered acinar cells (aa), and ducts (d) and blood vessels were surrounded by expanded fibrous connective tissue (fct). In the inset of (C) the black arrowhead identifies an eosinophil within the lumen. In addition to the numerous eosinophils within the acinar lumens, it appears that activated macrophages (black arrow) are present, as well as other blood cells. (D) Rabbits injected with CD4+ depleted lymphocyte preparations ID/CD4+ depleted had lymphocytic infiltration similar to ID/UF rabbits and less severe infiltration and fibrosis than ID/CD4+ enriched rabbits.

The LG of the ID/CD4+ enriched group exhibited the most severe histopathology (Fig. 3B). These lymphocytic infiltrates were larger than in the other groups and in some glands were detected throughout the gland, especially around ducts and venules and between acini. In many of the glands acinar morphology was dramatically altered, i.e., at times appearing involuted and duct-like; at other times appearing to undergo a mucoid transformation. Eosinophils were frequently evident within the lumens of acini, and occasionally neutrophils and macrophages were also present. Diseased glands induced with ID/CD4+ enriched preparations also contained large numbers of plump, pink-stained cells that have been seen in previous studies, albeit less abundant, when disease was induced with ID/UF.

The LG of the ID/CD4+ depleted group also were infiltrated by immune cells; but the histopathology was not as extensive as seen in the ID/CD4+ enriched group (i.e., lymphocytes were primarily located around ducts and venules). Rather, the lymphocytic foci were more comparable to those seen in the ID/UF group, as were the cytopathologic changes in the parenchyma. Most lobules appeared normal, although there was some evidence of involuted or collapsed acini that acquired a duct-like appearance. This latter observation was far less frequent in the ID/UF and ID/CD4+ depleted groups than in the ID/CD4+ enriched specimens.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen sections of LG from normal, ID/UF, ID/CD4+ enriched, and ID/CD4+ depleted groups were immunostained for CD4, CD8, MHC-II, RTLA and CD18. The quantitative data (i.e. percentages of cells expressing each marker) are summarized in Table 1. Strikingly, the number of CD4+ cells increased most (i.e. from 0.3% to 4.4%) in the ID/UF group, least in the ID/CD4+ enriched group (i.e. from 0.3% to 1.2%), and to an intermediate extent in the ID/CD4+ depleted group (i.e. from 0.3% to 2.95%). The number of CD8+ cells did not change significantly from the normal group in any of the experimental groups. The number of RTLA+ cells also increased most (from 1.6% to 6.2%) in the ID/UF group. The numbers of RTLA+ cells were similar to the total sum of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in the ID/UF group and the ID/CD4+ depleted group but were significantly greater in the normal group and the ID/CD4+ enriched group. Compared to the number of RTLA+ cells in the normal group, the numbers of RTLA+ cells increased roughly fourfold in the ID/UF group, 2.3-fold in the ID/CD4+ enriched group, and 1.7-fold in the ID/CD4+ depleted group. In contrast, the total number of bone marrow-derived cells expressing CD18, increased between 32-fold and 43-fold, with no significant difference between the three ID groups. The number of MHC II+ cells also increased more dramatically than the number of RTLA+ cells, roughly 85-fold in the ID/UF group and roughly 132-fold in the ID/CD4+ enriched and ID/CD4+ depleted groups.

Cytokine and CD Antigen mRNA Abundances

The sequences of rabbit genes for a number of cytokines and CD molecules made it possible to design primer and probe combinations for real time RT-PCR analyses to test for possible immunopathological differences between the dacryoadenitides induced by CD4+-enriched- and CD4+-depleted lymphocytes. The results are presented in Figure 4. ANOVA and tests for multiple comparisons indicated that mRNAs for IL-1β, CD4, CD8, IL-2 ,and IL-10 were significantly more abundant in one of the 9 glands from the ID/CD4+ enriched group, as well as in one of the 6 glands from the ID/CD4+ depleted group. These glands were considered atypical and were excluded from intergroup comparisons. mRNA extracts were available from only three ID/UF samples; because the sample size was so small, the calculated means and sems were not included in tests for multiple comparisons.

Figure 4. Abundances of CD molecule and cytokine mRNAs.

Abundances of target mRNAs relative to the abundance of GAPDH mRNA in each gland were determined by real time RT-PCR. Values presented are means ± sems for 5 normal glands, 3 glands from ID/UF animals, 8 glands from ID/CD4+ enriched animals, i.e., CD4(+), and 5 glands from ID/CD4+ depleted animals, i.e., CD4(−). Also presented are values for one additional gland each from the ID/CD4+ enriched group and the ID/CD4+ depleted group which were atypical with respect to several of the measured transcripts.

The typical glands from the ID/CD4+ enriched group differed from typical glands of the ID/CD4+ depleted group in having significantly higher abundances of mRNAs for the T cell surface markers, CD4 and CD8, and for, IL-2, a Th1 cytokine. mRNAs for IL-1β, which typically is associated with innate immune responses; IL-4, a Th2 cytokine; also appeared (0.055 ≤ P ≤0.076) to be more abundant in the typical glands from the ID/CD4+-enriched group than the typical glands from the ID/CD4+ depleted group. In contrast, the ID/CD4+ enriched and ID/CD4+ depleted groups did not differ from each other with respect to the abundances of mRNAs for TNF-α, a Th1 cytokine, and IL-10, which is a Th2 and regulatory cytokine.

DISCUSSION

The experiments described in Fig. 1 validated the hypothesis that CD4+ cells proliferate in AMCR with isolated lacrimal gland acinar cells. This is the result predicted if the acinar cells, which express MHC Class II molecules when they are isolated and placed in primary culture, function as surrogate antigen presenting cells. However, it is not possible to formally exclude the competing hypothesis that professional antigen presenting cells present in the acinar cell preparation provide the proximate antigenic signal to T cell antigen receptors.

The additional experiments in this study also accorded with the hypothesis that the CD4+ cells that proliferated in AMCR with isolated acinar cells would autoadoptively transfer disease independently of other cells that might be activated in the AMCR. However, they also led to the surprising findings that: (a) the CD4+ depleted cell fraction from the AMCR also contains pathogenic effector cells; (b) dacryoadenitides transferred by unfractionated cells from the AMCR, the CD4+ enriched fraction, and the CD4+ depleted fraction are immunopathophysiologically distinct; and (c) the adenitis autoadoptively transferred by the CD4+ depleted fraction is associated with significant ocular surface disease even though it does not impair lacrimal exocrine function as assessed by Schirmer’s test.

Of the three dacryoadenitides, the disease autoadoptively transferred by the CD4+ enriched fraction was associated with the most severe decrease in the Schirmer score, the most severe parenchymal cytopathology, the most prominent accumulation of eosinophils, and the most extensive periductal/perivascular fibrosis. In accord with the observed eosinophilic infiltration, the disease autoadoptively transferred by the CD4+ enriched fraction involved recruitment of CD18+ cells, a characteristic feature of bone marrow-derived cells. The combination of fibrosis, eosinophilic infiltration, and increased abundance of mRNA for the TH1 cytokine, TNF-α, particular suggests that the immunopathophysiological process in this disease resembles graft-versus-host disease (25, 26).

The dacryoadenitis autoadoptively transferred by unfractionated cells from the AMCR was characterized by the largest increase of the numbers of T cells, expressing RTLA, infiltrating the glands, but also by an increase in the number of CD18+ cells not statistically different from the numbers in other dacryoadenitides. The makeup of populations of bone marrow-derived cells recruited to the glands remain to be determined. However, the magnitude of the increase of CD4+ cells unaccompanied by an increased number of CD8+ cells, and the less extensive eosinophilic infiltration suggest that the immunopathophysiological process in this disease might most closely resemble that of Sjögren’s syndrome(14, 27).

The pathophysiological process transferred by the CD4+ depleted fraction involved a large increase of CD18+ cells infiltrating the gland, but no significant increase in the number of RTLA+ cells. Notably, the proportion of CD4+ cells increased to essentially 100% of the RTLA+ population, while the proportion of CD4−CD8− cells decreased dramatically. Moreover, mRNAs for CD4 and IL-4, as well as for CD8, were significantly less abundant than in the disease induced by the CD4+ enriched fraction. These features suggest an immunopathophysiological process that involves bone marrow-derived cells and CD4+ T cells that do not clearly express TH2 characteristics. Furthermore, while this dacryoadenitis was, like the others, associated with significant ocular surface pathology, it was associated with at best a mild decrease in the Schirmer scores in OD and no change of the Schirmer scores in OS. Thus, this process differs from both Sjögren’s dacryoadenitis and graft-versus-host-disease dacryoadenitis in its apparent lack of impact on lacrimal fluid production. It seems plausible that this might resemble the typical dacryoadenitis associated with aging, the incidence of which greatly exceeds the incidence of clinical dry eye disease (8, 9). If so, it represents the first time such an adenitis has been induced in an experimental model.

This study suggests several directions for further work. It should be possible to use laser capture microdissection methods to sample lymphocytic aggregates, acinar- and ductal parenchymal tissue near the aggregates, and parenchymal tissue further separated from the aggregates for RT-PCR studies addressing the cytokine and CD antigen expression profiles of each. Given that it is possible to cannulate the main excretory ducts of the rabbit lacrimal gland, it should be possible to determine whether the protein or electrolyte composition of lacrimal gland fluid changes in the model of dry eye disease without exocrine insufficiency. Thus, it would be possible to test the standard assumption that a deficiency of tear quality is responsible for the ocular surface signs and symptoms of those patients who present with dry eye complaints but no evident decrease of lacrimal exocrine function.

It should be possible to design studies to identify the specific inflammatory mediators that cause exocrine dysfunction or quiescence in the models that resemble Sjögren’s syndrome and graft-versus-host disease. It also should be possible to apply the approaches that have now been developed to study the cornea and conjunctiva and learn whether the inflammatory processes associated with experimentally induced dry eye disease differ between the lacrimal glands and the ocular surface tissues. Finally it should be possible to learn whether current and prospective therapies are more effective against one or another of the pathophysiologically distinct dacryoadenitides. Conversely, it is now realistic to contemplate devising new therapies that specifically target each of the dacryoadenitides.

In addition to providing new models for studying the immunopathophysiology and therapy of dacryoadenitis and dry eye disease, this study may also be relevant to aspects of their etiologies. They demonstrate that parenchymal cells critically influence the behavior of CD4+ T cells and bone marrow-derived cells as well. Lacrimal gland immunopathophysiology in the rabbit fails to model disease in humans in that parenchymal cells in the rabbit lacrimal gland can rarely be found expressing MHC Class II. Thus, the antigen presenting function they take on when isolated and placed in primary culture provides useful models for cytophysiological and immunophysiological studies, but it is not likely to be an important mechanism in lacrimal gland disease in the rabbit. The contrary is likely the case in human lacrimal glands, and in rodent models. There may be closer similarity between other aspects of the immunopathophysiological mechanisms in humans and rabbits, particularly in the roles of paracrine mediators that the parenchymal cells express. Rather direct evidence already has emerged that one of these, prolactin, influences the activities of T cells present in the gland(28) , while others, including TGF-β and IL-10 influence the phenotypic expression of at least one bone marrow-derived lineage, monocytes maturing into dendritic cells(29).

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of inflammatory cells in lacrimal glands.

| Group | CD 4 | CD8 | MHC II | RTLA | CD 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Mean Positive Percentage ± SE |

0.3 ± 0.02 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| ID/UF Mean Positive Percentage ± SE |

4.4 ± 0.91 (p1=0.003) |

0.67 ± 0.24 | 8.49 ± 0.39 (p1=0.001) |

6.2 ± 0.9 (p1=0.003) |

8.7 ± 0.61 (p1=0.001) |

| ID/CD4+ enriched Mean Positive Percentage ± SE |

1.2 ± 0.26 (p1=0.01) (p2=0.003) |

1.04 ± 0.32 | 13.1 ± 1.73 (p1=0.001) (p2=0.02) |

3.7 ± 0.63 (p1=0.05) |

6.4 ± 0.59 (p1=0.001) (p2=0.003) |

| ID/CD4+ depleted Mean Positive Percentage ± SE |

2.95 ± .93 (p1=0.01) (p3=0.05) |

0.84 ± 0.54 | 13.34 ± 2.09 (p1=0.001) (p2=0.01) |

2.75 ± 0.3 | 6.71 ± 1.07 (p1=0.001) (p3=0.05) |

- p1: Represents the p value for significance between “Normal” and the other three groups.

- p2: Represents the p value for significance between ID/UF and ID/CD4+ enriched and ID/CD4+ depleted groups.

- p3: Represents the p value for significance between ID/CD4+ enriched and ID/CD4+ depleted groups.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Deming Sun for his scientific advice, Laurie LaBree Dustin for statistical analysis, and Ernesto Barren for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants EY12689, EY05801, EY10550, and EY03040; an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.; and a grant to Mel Trousdale from Allergan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interest

None

Author’s contributions

PBT participated in the acquisition of data, data analysis, interpretation and manuscript preparation. DMS participated in the acquisition of data and data analysis. YW participated in the acquisition of PCR data. SS participated in acquisition of data, DS participated in the acquisition of data, and manuscript preparation. JDG participated in the acquisition and interpretation of FACS data. JES participated in the evaluation and interpretation of histopathology data. AKM and MDT participated in the design of the study, interpretation of the data and manuscript preparation.

Contributor Information

Padmaja B. Thomas, Email: pthomas@doheny.org.

Deedar M. Samant, Email: dsamant@doheny.org.

Yanru Wang, Email: yanruwan@gmail.com.

Shivaram Selvam, Email: Selvam@me.gatech.edu.

Douglas Stevenson, Email: dstevenson@doheny.org.

John D. Gray, Email: jdgray@usc.edu.

Joel E. Schechter, Email: schechte@usc.edu.

Austin K. Mircheff, Email: amirchef@usc.edu.

References

- 1.Bardos T, Mikecz K, Finnegan A, Zhang J, Glant TT. T and B cell recovery in arthritis adoptively transferred to SCID mice: antigen-specific activation is required for restoration of autopathogenic CD4+ Th1 cells in a syngeneic system. J Immunol. 2002;168:6013–6021. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berlo SE, van Kooten PJ, Ten Brink CB, Hauet-Broere F, Oosterwegel MA, Glant TT, Van Eden W, Broeren CP. Naive transgenic T cells expressing cartilage proteoglycan-specific TCR induce arthritis upon in vivo activation. J Autoimmun. 2005;25:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maffia P, Brewer JM, Gracie JA, Ianaro A, Leung BP, Mitchell PJ, Smith KM, McInnes IB, Garside P. Inducing experimental arthritis and breaking self-tolerance to joint-specific antigens with trackable, ovalbumin-specific T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:151–156. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pepose JS, Akata RF, Pflugfelder SC, Voigt W. Mononuclear cell phenotypes and immunoglobulin gene rearrangements in lacrimal gland biopsies from patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1599–1605. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pflugfelder SC, Wilhelmus KR, Osato MS, Matoba AY, Font RL. The autoimmune nature of aqueous tear deficiency. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:1513–1517. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsubota K, Toda I, Yagi Y, Ogawa Y, Ono M, Yoshino K. Three different types of dry eye syndrome. Cornea. 1994;13:202–209. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damato BE, Allan D, Murray SB, Lee WR. Senile atrophy of the human lacrimal gland: the contribution of chronic inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:674–680. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.9.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obata H. Anatomy and histopathology of the human lacrimal gland. Cornea. 2006;25:S82–S89. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000247220.18295.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obata H, Yamamoto S, Horiuchi H, Machinami R. Histopathologic study of human lacrimal gland. Statistical analysis with special reference to aging. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:678–686. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30971-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roen JL, Stasior OG, Jakobiec FA. Aging changes in the human lacrimal gland: role of the ducts. Clao J. 1985;11:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson J, Gibson AA, Wilson T, Forrester JV, Whaley K, Dick WC. Histology of the lacrimal gland in keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Br J Ophthalmol. 1973;57:852–858. doi: 10.1136/bjo.57.11.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mircheff AK, Gierow JP, Lee LM, Lambert RW, Akashi RH, Hofman FM. Class II antigen expression by lacrimal epithelial cells. An updated working hypothesis for antigen presentation by epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2302–2310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolstad AI, Jonsson R. Genetic aspects of Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:353–359. doi: 10.1186/ar599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonsson MV, Delaleu N, Brokstad KA, Berggreen E, Skarstein K. Impaired salivary gland function in NOD mice: association with changes in cytokine profile but not with histopathologic changes in the salivary gland. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2300–2305. doi: 10.1002/art.21945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen CQ, Peck AB. Unraveling the pathophysiology of Sjogren syndrome-associated dry eye disease. Ocul Surf. 2009;7:11–27. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70289-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Draper CE, Singh J, Adeghate E. Effects of age on morphology, protein synthesis and secretagogue-evoked secretory responses in the rat lacrimal gland. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;248:7–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1024159529257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rios JD, Horikawa Y, Chen LL, Kublin CL, Hodges RR, Dartt DA, Zoukhri D. Age-dependent alterations in mouse exorbital lacrimal gland structure, innervation and secretory response. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:477–491. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo Z, Azzarolo AM, Schechter JE, Warren DW, Wood RL, Mircheff AK, Kaslow HR. Lacrimal gland epithelial cells stimulate proliferation in autologous lymphocyte preparations. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:11–22. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo Z, Song D, Azzarolo AM, Schechter JE, Warren DW, Wood RL, Mircheff AK, Kaslow HR. Autologous lacrimal-lymphoid mixed-cell reactions induce dacryoadenitis in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:23–31. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas PB, Zhu Z, Selvam S, Samant DM, Stevenson D, Mircheff AK, Schechter JE, Song SW, Trousdale MD. Autoimmune dacryoadenitis and keratoconjunctivitis induced in rabbits by subcutaneous injection of autologous lymphocytes activated ex vivo against lacrimal antigens. J Autoimmun. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Z, Stevenson D, Schechter JE, Mircheff AK, Atkinson R, Trousdale MD. Lacrimal histopathology and ocular surface disease in a rabbit model of autoimmune dacryoadenitis. Cornea. 2003;22:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Z, Stevenson D, Ritter T, Schechter JE, Mircheff AK, Kaslow HR, Trousdale MD. Expression of IL-10 and TNF-inhibitor genes in lacrimal gland epithelial cells suppresses their ability to activate lymphocytes. Cornea. 2002;21:210–214. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200203000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trousdale MD, Zhu Z, Stevenson D, Schechter JE, Ritter T, Mircheff AK. Expression of TNF inhibitor gene in the lacrimal gland promotes recovery of tear production and tear stability and reduced immunopathology in rabbits with induced autoimmune dacryoadenitis. J Autoimmune Dis. 2005;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1740-2557-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji Q, Chang L, VanDenBerg D, Stanczyk FZ, Stolz A. Selective reduction of AKR1C2 in prostate cancer and its role in DHT metabolism. Prostate. 2003;54:275–289. doi: 10.1002/pros.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jabs DA, Wingard J, Green WR, Farmer ER, Vogelsang G, Saral R. The eye in bone marrow transplantation. III. Conjunctival graft-vs-host disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1343–1348. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020413046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogawa Y, Yamazaki K, Kuwana M, et al. A significant role of stromal fibroblasts in rapidly progressive dry eye in patients with chronic GVHD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi M, Mimura Y, Hamano H, Haneji N, Yanagi K, Hayashi Y. Mechanism of the development of autoimmune dacryodenitis in the mouse model for primary Sjogren's syndrome. Cell Immunol. 1996;170:54–62. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mircheff AKWY, Nakamura T, Thomas PB, Trousdale MD, Warren DW, Schechter JE. Hormones and Environment in Inflammatory Lacrimal Gland Disease ARVO. Fort Lauderdale. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Saint Jean M, Nakamura T, Wang Y, Trousdale MD, Schechter JE, Mircheff AK. Suppression of lymphocyte proliferation and regulation of dendritic cell phenotype by soluble mediators from rat lacrimal epithelial cells. Scand J Immunol. 2009;70:53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]