Abstract

Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from somatic cells using defined factors has potential relevant applications in regenerative medicine and biology. However, this promising technology remains inefficient and time consuming. We have devised a serum free culture medium termed iSF1 that facilitates the generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. This optimization of the culture medium is sensitive to the presence of Myc in the reprogramming factors. Moreover, we could reprogram meningeal cells using only two factors Oct4/Klf4. Therefore, iSF1 represents a basal medium that may be used for mechanistic studies and testing new reprogramming approaches.

Keywords: Chromatin, Embryonic Stem Cell, Stem Cell, Transcription Factors, Tumor Metabolism, Viral Protein

Introduction

The discovery that four transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc can revert differentiated somatic cells to a pluripotent state resembling embryonic stem cells (ESCs)3 (1–4) not only demonstrates the remarkable plasticity of the mammalian genome, but also offers a unique opportunity to investigate the mechanisms associated with cell fate determination at the molecular level (5, 6). Besides, human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) overcome ethical issues associated with human ESCs and the risk of immune rejection (7, 8). However, the reprogramming process remains largely an art form, with low efficiency and inconsistency among different experimental settings (1, 3, 4, 6). Nowadays, the mouse system remains the model in which many mechanistic/technical breakthroughs are achieved. Therefore, albeit more robust than the human setting, it is important to improve mouse iPSC generation to achieve a better understanding of nuclear reprogramming. Here, we report an optimized method to generate mouse iPSCs consistently with high efficiency that is potentially useful for multiple applications including screening for small molecules, dissection of molecular mechanisms, and testing of new methods.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were derived from day 13.5 embryos (e13.5) hemizygous for the Oct4-GFP transgenic allele (9, 10) and Rosa26 allele and were maintained in fibroblast medium: DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine, and non-essential amino acid. iPSCs and ESCs were routinely expanded on MEF feeder layers (MEFs inactivated with mitomycin C) in both FBS-containing medium (mES) or KSR medium. mES medium consisted of DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS, l-glutamine, NEAA, sodium pyruvate, penicillin/streptomycin, β-mercaptoethanol, and 1000 units/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (Millipore). KSR medium consisted of knock-out DMEM supplemented with 15% knock-out Serum Replacement (SR), l-glutamine, NEAA, penicillin/streptomycin, β-mercaptoethanol, and 1000 units/ml LIF. fSF1 consisted of DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% SR, 1/200 N2, l-glutamine, NEAA, penicillin/streptomycin, 1000 units/ml LIF, and 5 ng/ml basic FGF. iSF1 was like fSF1 but contained high glucose DMEM. Unless otherwise indicated, all reagents were purchased from Invitrogen. The FBS lot number was 709778, which was used in our previous study for supporting reprogramming (11).

Retrovirus Production and Generation of iPSCs

Retroviral vectors (pMX-based) containing the murine cDNAs of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc were purchased from Addgene. These plasmids were transfected into PlatE cells using a calcium phosphate transfection protocol. MEFs within three passages were split when they reached 80–90% confluence and plated at 4000–5000 cells/cm2 12 h before infection. Viral supernatants were collected and filtered 48 h later to infect MEFs supplemented with 4 μg/ml Polybrene. The same procedure was repeated the following day. The day that viral supernatants were removed was defined as day 0 post-infection. In the gradual replacement (GR) strategy, the cells were cultured in fSF1 after the viral supernatants were removed, and then the medium was gradually replaced by KSR in a 4-day stepwise process. iPSC colonies were picked between 10 and 15 days postinfection based on Oct4-GFP expression and typical ESC-like morphology. Picked colonies were subsequently expanded and maintained as ESCs.

Quantification of Reprogramming Efficiency

For the GR method we counted GFP+ colonies under a fluorescent microscope at day 14 postinfection, for iSF1 at day 8 or day 10 postinfection. For confirming these results, infected MEFs were also trypsinized between days 7 and 9 postinfection and then analyzed using a FACS Calibur machine without any gate on the SSC/FSC channels. GFP+ cells were gated with a control signal from the PE channel, and a minimum of 10,000 events were recorded. Cells infected with pMX-FLAG were used as negative control.

Alkaline Phosphatase and Immunofluorescence Staining

Alkaline phosphatase and immunofluorescence staining were performed as previously described (11). The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-Oct4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-SSEA-1 (Abcam), mouse anti-Nanog, and mouse anti-Rex1 (produced by us).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR)

Total mRNA was isolated using TRIzol, and 2 μg was used to synthesize cDNA using ReverTra Ace® (Toyobo) and oligo(dT) (Takara). qPCR was performed using Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara) and analyzed with an ABI 7300 machine. Primers sequences are shown in supplemental Table 1.

Teratoma Formation and Blastocyst Injection

Teratomas were produced by injecting 2 million cells subcutaneously into SCID mice. Tumor samples were collected within 4 weeks, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and processed for paraffin embedding and hematoxylin and eosin staining following standard procedures. Chimeras were produced by injecting iPSCs into blastocysts derived from ICR mice, followed by implantation into pseudopregnant ICR mice.

Bisulfite Sequencing

Genomic DNA (700 ng) from various cell lines was exposed overnight to a mixture of 50.6% sodium bisulfite (Sigma) and 10 mm hydroquinone (Sigma). Afterward, a region from the Nanog proximal promoter was amplified by PCR using primers described previously (11). The PCR products were cloned into pMD18-T vector (Takara), propagated in DH5α, and sequenced.

Whole Genome Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells and purified using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Three micrograms of total RNA was used for the reverse transcription reaction primed with T7-Oligo(dT) promoter (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) using Superscript II (Invitrogen). Biotin-labeled cRNA was synthesized by in vitro transcription using Bioarray RNA Transcript Labeling kit (Affymetrix). After being fragmented, the cRNA were hybridized to a mouse Affymetrix (mouse 430 2.0). Array were scanned with a GeneArray Scanner 7G (Affymetrix). Data in the form of CEL files were background-subtracted and normalized with the Robust Multi-chip Average method and ArrayAssist 5.0 software (Stratagene). Data of microarray are available on Gene Expression Omnibus GSE15267.

Compound Screening

MEFs were seeded on 12-well plates with 20,000 cells/well and infected as described above. One day after infection various compounds were added until cells were analyzed by FACS. The following compounds were used: PD0325901 (1 μm), CHIR99021 (3 μm), SU5402 (2 μm; EMDbiosciences), Y-27632 (10 μm), vitamin E (25 μm; Sigma), vitamin A (1 μm; Sigma), A83-01 (0.5 μm; EMD), SB203580 (2 μm), dorspmorphin (3 μm; Sigma), trichostatin A (20 nm; Sigma), valproic acid (1 mm or 2 mm; EMD), JAK inhibitor (0.3 μm; EMD), 5-Aza-dC (1 μm; Sigma), BIX01294 (1 μm), and Bayk8644 (2 μm; EMD).

RESULTS

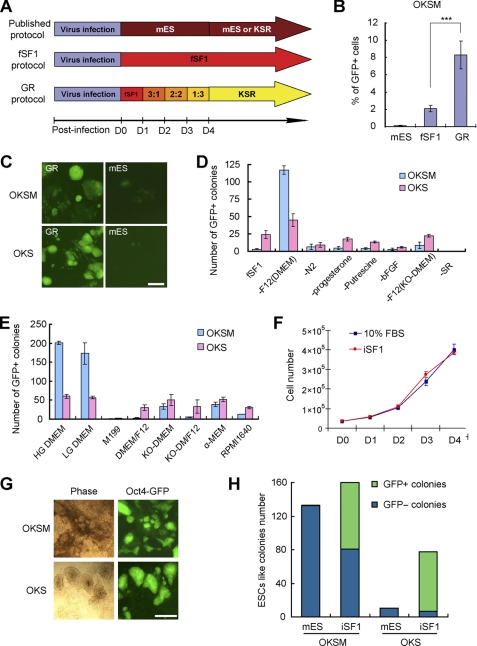

Typically, murine iPSCs can be generated from MEFs in about 2 weeks, and this requires FBS and feeders to reach 0.01∼0.5% efficiency (1–4, 6). This inefficient process and undefined culture conditions are a roadblock for both drug screening and mechanistic insights (6, 12, 13). Thus, it is desirable to use a serum-free medium such as medium containing SR (supplemental Table 2). KSR medium cannot support the proliferation of MEFs (supplemental Fig. 1A). However, iPSC colonies can be obtained efficiently when FBS-containing medium (mES) is switched to KSR at day 4 postinfection (10). After testing candidate factors systematically, we developed a medium (fSF1) containing SR, basic FGF, and N2 (supplemental Table 2). fSF1 allows MEFs (from OG2/Rosa26 mice carrying the Oct4-GFP marker) to grow well and reprogram more efficiently than using mES based on the number of Oct4-GFP+ cells detected by FACS (Fig. 1, A and B, and supplemental Fig. 1, A and B). We also tested a GR of fSF1 with KSR (Fig. 1A), and this GR approach further improved reprogramming as measured by FACS or counting GFP+ colonies using either MEFs or skin fibroblasts as donor cells (Fig. 1, B and C, and supplemental Fig. 1, C and D). As previously reported (14), we failed to reprogram MEFs using N2B27 medium supplemented with PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor), CHIR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor), and LIF (supplemental Fig. 1, E and F).

FIGURE 1.

Optimization of the culture medium for efficient reprogramming induced by defined factors. A, time line of GR strategy is compared with a published protocol (1, 10). D indicates day. B, MEFs infected with Oct4/Sox2/Klf4/Myc (OKSM) were cultured in mES medium, fSF1, and GR protocol for 7 days. The percentage of Oct4-GFP+ cells was measured by FACS; n = 4. ***, p < 0.001. C, representative pictures are shown at day 14 postinfection in OKSM- and OKS-infected MEFs with GR strategy compared with infected MEFs in control mES medium. Scale bar, 250 μm. D, MEFs infected with OKSM or OKS were cultured in modified fSF1 medium eliminating different components. Oct4-GFP+ colonies were counted at day 7 postinfection; n = 3. E, MEFs infected with OKSM or OKS were cultured in modified iSF1 medium containing different basal media. Oct4-GFP+ colonies were counted at day 8 postinfection; n = 2. F, growth curve of MEFs in fibroblast medium containing 10% FBS or iSF1 medium is shown; n = 3. G, representative images of OKSM and OKS iPSC colonies produced in iSF1 at day 14 postinfection are shown. Cells were not split on feeders. Scale bar, 500 μm. H, MEFs infected with OKSM or OKS were cultured in mES or iSF1. The number of GFP+ colonies (green bars) and GFP− colonies (blue bars) were scored at day 8 postinfection; n = 3. All error bars indicate S.D.

We then simplified the GR protocol by formulating a medium that does not require a gradual replacement. For this we tested the relative contribution of all components present in fSF1 and KSR. As shown in Fig. 1D, we discovered that the selection of basal medium is critical. Of eight basal media screened, we found that DMEM, especially the high glucose DMEM, was the most suitable basal medium for reprogramming (Fig. 1E and supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). We then replaced the basal medium of fSF1 with high glucose DMEM and renamed it iSF1 (supplemental Table 2). iSF1 supports MEF growth as well as FBS-containing medium (Fig. 1F) but allows very high efficiency of reprogramming induced either by OKSM (Oct4/Klf4/Sox2/Myc) or OKS (Oct4/Klf4/Sox2) (Fig. 1, D, E, and G). When used throughout the reprogramming protocol, iSF1 also improves the reprogramming kinetics over the GR protocol (supplemental Fig. 2C). By adding or eliminating basic FGF in iSF1, we confirmed that basic FGF is important for optimal iPSC generation efficiency (supplemental Fig. 2D). By comparing the number of incomplete reprogrammed colonies (GFP−) and GFP+ colonies, we found that the improvement induced by iSF1 may differ mechanistically between OKSM and OKS (Fig. 1H). In OKSM-infected MEFs, high efficiency appears to be achieved through the conversion of GFP− colonies to fully reprogrammed ones, whereas in OKS the total number of colonies increased, and most of them were GFP+, thus suggesting that an increased number of cells have initiated the reprogramming.

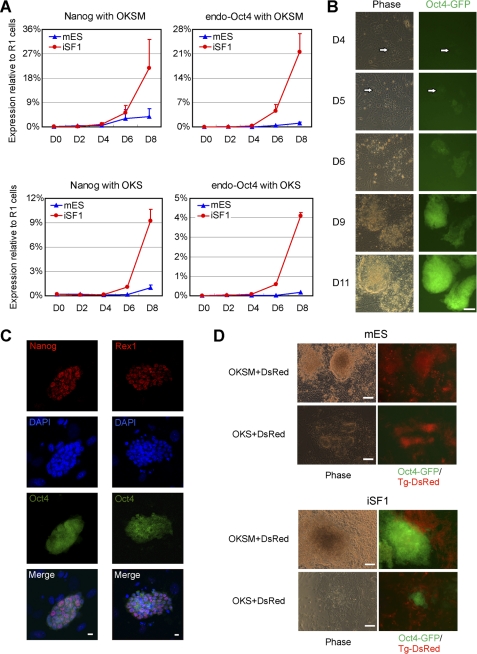

To demonstrate that iSF1 also accelerates the conversion into iPSCs we detected the expression of pluripotent markers in the reprogramming process. iSF1 enhances the expression of Nanog and endogenous Oct4 significantly in MEFs infected with OKSM and OKS (Fig. 2A). iSF1 also allows the appearance of small numbers of GFP+ cells at day 4 postinfection that later on transform into GFP+ colonies (Fig. 2B). Reactivation of pluripotent genes (such as Nanog and Rex1) can be detected by immunofluorescence in iPSC colonies as early as day 10 postinfection (Fig. 2C). Retroviral silencing has been defined as a late event that indicates full reprogramming (15, 16). We used DsRed as a reporter for viral silencing and observed Oct4-GFP+/DsRed-colonies emerging at day 9 postinfection (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Optimized medium iSF1 supports rapid reprogramming induced by defined factors. A, time course detection by qPCR of Nanog and endogenous Oct4 in OKSM- or OKS-infected cells cultured in the indicated medium. Expression values were normalized using GAPDH and refer to the expression level of R1; n = 2. D indicates day. Error bars indicate S.D. B, further examples of iPSC colonies generated from Oct4-GFP+ cells spotted at an early time point. MEFs were infected with OKS. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, immunofluorescence staining showing expression of pluripotency markers Nanog and Rex1 in colonies at day 10 postinfection. Nuclei are stained with DAPI and show that feeder cells do not express Nanog or Rex1. Scale bars, 10 μm. D, MEFs were infected with either OKSM or OKS together with DsRed and then cultured for 9 days with either iSF1 or mES medium. Expression of the Oct4-GFP and the transgene DsRed (Tg-DsRed) was examined by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bars, 100 μm.

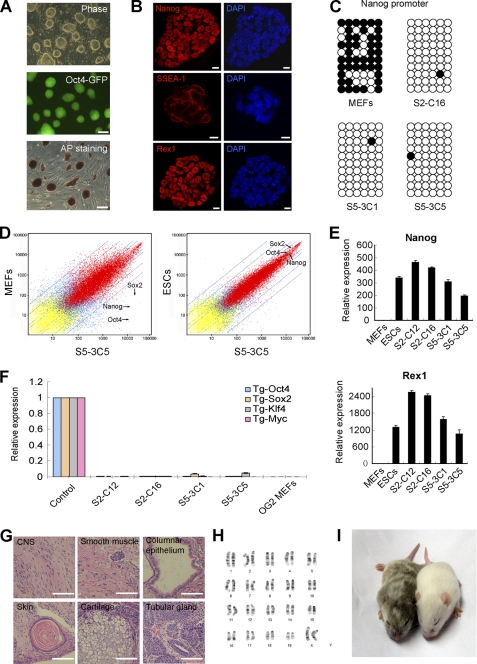

iPSC clones established from cultures in iSF1 maintained strong Oct4-GFP expression (Fig. 3A) and were alkaline phosphatase, Nanog, Rex1, and SSEA-1 positive (Fig. 3, A and B). These cell lines also displayed a demethylated Nanog proximal promoter (Fig. 3C). DNA microarray analysis demonstrated as well that these iPSCs have an expression profile similar to that of mouse ESCs (Fig. 3D). The pluripotent markers Nanog and Rex1 were reactivated and the transgenes potently silenced in all four iPS cell lines tested as measured by qPCR (Fig. 3, E and F). These iPSCs could produce teratomas containing tissues derived from all three germ layers and had normal karyotypes (Fig. 3, G and H). Moreover, when injected into blastocysts, they efficiently produced chimeric mice (Fig. 3I).

FIGURE 3.

iPSCs derived from iSF1 medium resemble mouse ESCs. A, morphology, Oct4-GFP+ expression and alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining of iPSCs produced with iSF1. Scale bars, 100 μm. B, immunofluorescence staining showing expression of pluripotency genes such as Rex1, SSEA-1, and Nanog in iPSCs produced in iSF1. Scale bars, 10 μm. C, Nanog promoter methylation analysis in iPSCs derived from iSF1. Bisulfite sequencing data of 10 clones for each sample are shown. Open circles indicate unmethylated CpG dinucleotides, and filled circles indicate methylated CpG dinucleotides. D, global expression profiles of S5-3C5, MEFs, and R1. Arrows show the expression of pluripotent genes Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog. E, expression levels of Nanog and Rex1 in MEFs, R1, and iPSCs relative to 18 S as assessed by qPCR. Values from MEFs were set to 1. F, expression levels of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc transgenes (relative to 18 S) assessed by qPCR. Values from infected MEFs (isolated at day 6 postinfection) were set to 1. Uninfected MEFs were used as negative control. G, Teratomas differentiated from iPSCs (S5-3C5) containing all three embryonic germ layers: central nervous system (CNS) and skin (ectoderm), muscle and cartilage (mesoderm), columnar epithelium and tubular gland (endoderm). Scale bars, 100 μm. H, karyotype of iPSCs produced with iSF1. We examined three iPSC lines, and all of them showed normal karyotype. I, chimeric mice generated using iPSCs produced with iSF1. iPSC-derived cells are responsible for the agouti coat color. The mouse on the right is the control.

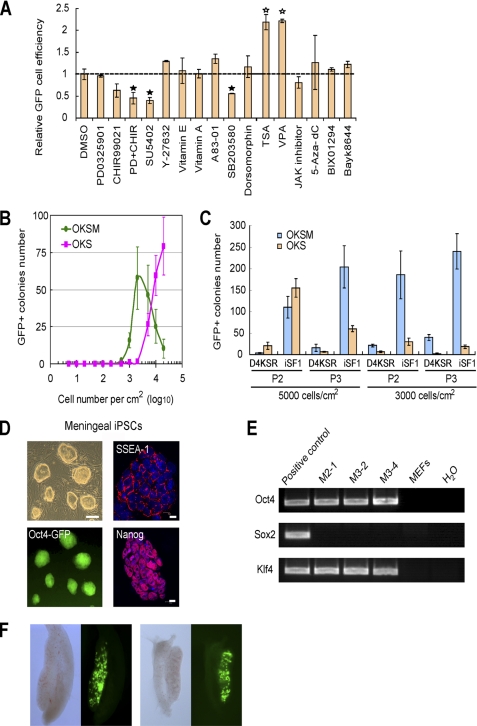

Given the above shown results, iSF1 may be useful as a basal medium for screening compounds (13) that enhance or reduce reprogramming or replace one of the reprogramming factors (17). We tested 16 compounds known to affect reprogramming or pluripotency (5, 12, 14, 18–20), but most of them could not enhance it further in our optimized condition (Fig. 4A). Only trichostatin A and valproic acid, two histone deacetylase inhibitors, were able to increase the reprogramming substantially (Figs. 4A and supplemental Fig. 2, E and F). Interestingly, we also observed that OKS-infected MEFs are more sensitive to the starting culture conditions, such as density and passage, than OKSM-infected MEFs (Fig. 4, B and C). A possible explanation is that Myc may antagonize senescence and apoptosis triggered by late passage or low density. On the other hand, the efficiency of OKSM-mediated iPSC generation is more susceptible to changes in the basal medium (Fig. 1E), again suggesting that the reprogramming process induced by OKSM and OKS may follow different routes. In the most optimal condition and using Oct4-GFP+ colony number at day 8 postinfection as criterion, the efficiency of reprogramming with OKSM is 2.89 ± 1.05%, and with OKS is 0.595 ± 0.135% (Fig. 4B), which is ∼300-fold and 500-fold higher than standard mES medium, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

iSF1 is an optimized medium for reprogramming research. A, screening of 16 compounds suggesting iSF1 screening potential. The efficiency was analyzed by FACS at day 8 postinfection. The broken line shows the value of control sample whose value was set to 1. Open pentagram indicates a >40% improvement; filled pentagram indicates a >40% decrease; n = 2. Error bars, S.D. B, passage 2 MEFs seeded with indicated densities from 5 cells/cm2 to 20,000 cells/cm2 and infected with OKSM or OKS. Oct4-GFP+ colonies were counted at day 8 postinfection; colonies/cm2 are shown; n = 4. C, passage 2 or 3 MEFs seeded in two densities: 3,000 cells/cm2 and 5,000 cells/cm2 and infected with OKSM or OKS. These cells were cultured in two protocols: day 4 changing to KSR from mES (D4KSR), and iSF1. GFP+ colonies were counted at day 8 postinfection. The results show the mean of two independent experiments, each of them in duplicate. D, iPSC clones derived from meningeal cells with Oct4 and Klf4 (OK mg-iPSCs) showing ESC-like morphology, expressing Oct4-GFP, SSEA-1, and Nanog. E, integration analysis confirming the identity of OK mg-iPSC clones. The presence of retroviral transgenes was examined by PCR. F, OK mg-iPSCs contribute to germ line cells of chimeric mouse. Genital ridges of e12.5 chimeras were isolated, and GFP expression indicates the contribution of OK mg-iPSCs. Left panel is female, and right panel is male.

Considering that iSF1 enhances MEFs reprogramming significantly, we wondered whether meningeal cells, which express endogenous Sox2 and reprogram more efficiently than fibroblasts (11), can be transformed into iPSCs with fewer factors in iSF1. Meningeal cells failed to be reprogrammed by Oct4 and Klf4 in standard mES medium (data not shown), which might be because the expression of endogenous Sox2 is lower than neural stem cells (data not shown). However, we could produce iPSCs using only Oct4 and Klf4 in iSF1, whereas no colonies emerged in mES medium in four independent experiments (Fig. 4D). These OK meningeal iPSC clones express Oct4-GFP, SSEA-1, and Nanog, indicating that they are pluripotent (Fig. 4D). Examination of retroviral integration in the genomic DNA confirmed that these clones contained only Oct4 and Klf4 (Fig. 4E). When injected into blastocysts, OK meningeal iPSCs contributed to germ line cells of chimeric mouse as determined by activation of the Oct4-GFP reporter (Fig. 4F). Therefore, optimization of the culture conditions not only accelerates reprogramming, but also reduces the need for some reprogramming factors.

DISCUSSION

Here, we describe an optimized tissue culture condition that allows efficient generation of mouse iPSCs. The combination of SR, basic FGF, and N2 can significantly improve the reprogramming efficiency and also the kinetics. SR contains abundant vitamin C, which enhances reprogramming remarkably especially when added as the more stable 2-phospho-l-ascorbic acid trisodium salt (21). Lipids in SR are also known to regulate ESC self-renewal and might contribute to the reprogramming as well (22). On the other hand, basic FGF and N2 seem to act by promoting cell proliferation (supplemental Fig. 1B), which may allow the acquisition of stochastic changes during the reprogramming (23). SR and basic FGF are routinely used in human iPSC generation, which in general yields much lower efficiencies than the mouse (7, 8). This may be related to different requirements of mouse and human somatic cells to achieve the induced pluripotent status.

Compared with other reported reprogramming media, iSF1 represents a good option for several reasons. It eliminates many undefined factors present in serum although some others still remain in SR. For example the lipid-rich albumin is not chemically defined (22), but its elimination can serve as a screening system for formulating a better defined medium. Furthermore, given the speed of the process and the high efficiency, iSF1 may prove very useful for mechanistic research perhaps using enriched populations sorted by FACS. iSF1 may prove useful as well to test new reprogramming techniques, especially nonintegrating approaches, as for example we could effectively reprogram meningeal cells using only two factors.

One surprising finding is that the basal medium appears to be of critical importance because DMEM is permissive but other media are not. This offers the possibility of screening among the components of such media for elements that influence the reprogramming. In addition, consistent with previous reports (15, 24, 25), many incompletely reprogrammed colonies were observed in OKSM-mediated reprogramming even in the presence of iSF1, whereas OKS mostly generated fully reprogrammed iPSCs. This difference suggests that our protocol is more optimal for OKS than OKSM. The latter may help highlight differential roles of Myc during the reprogramming, which may be both positive and negative depending on the context. Our laboratory is currently testing this idea as well as others mentioned above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Baoming Qin, Jialiang Liang, and Hongling Wu for constructive criticism and Haixiang Zhang, Yu Zhang, Kang Deng, Lin Guo, Hanquan Liang, and Wanfen Peng for technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30630039, 30700410, 30871404, and 90813033; National Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars Grant 30725012; Knowledge Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Grants KSCX2-YW-R-48 and KSCX1-YW-02-1; Bureau of Science and Technology of Guangzhou Municipality Grant 2008A1-E4011; and Ministry of Science and Technology 973 program of China Grants 2006CB943600, 2007CB948002, 2007CB947804, 2007CB947900, 2009CB941102, and 2009CB940902.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1 and 2.

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- GR

- gradual replacement

- iPSC

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- qPCR

- quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- LIF

- leukemia inhibitory factor

- NEAA

- non-essential amino acid

- SR

- Serum Replacement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. (2006) Cell 126, 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin D., Li W., Zhang J., Pei D. (2007) Cell Res. 17, 959–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okita K., Ichisaka T., Yamanaka S. (2007) Nature 448, 313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wernig M., Meissner A., Foreman R., Brambrink T., Ku M., Hochedlinger K., Bernstein B. E., Jaenisch R. (2007) Nature 448, 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikkelsen T. S., Hanna J., Zhang X., Ku M., Wernig M., Schorderet P., Bernstein B. E., Jaenisch R., Lander E. S., Meissner A. (2008) Nature 454, 49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maherali N., Hochedlinger K. (2008) Cell Stem Cell 3, 595–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., Narita M., Ichisaka T., Tomoda K., Yamanaka S. (2007) Cell 131, 861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu J., Vodyanik M. A., Smuga-Otto K., Antosiewicz-Bourget J., Frane J. L., Tian S., Nie J., Jonsdottir G. A., Ruotti V., Stewart R., Slukvin II, Thomson J. A. (2007) Science 318, 1917–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szabó P. E., Hübner K., Schöler H., Mann J. R. (2002) Mech. Dev. 115, 157–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blelloch R., Venere M., Yen J., Ramalho-Santos M. (2007) Cell Stem Cell 1, 245–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin D., Gan Y., Shao K., Wang H., Li W., Wang T., He W., Xu J., Zhang Y., Kou Z., Zeng L., Sheng G., Esteban M. A., Gao S., Pei D. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33730–33735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y., Do J. T., Desponts C., Hahm H. S., Schöler H. R., Ding S. (2008) Cell Stem Cell 2, 525–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y., Shi Y., Ding S. (2008) Nature 453, 338–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva J., Barrandon O., Nichols J., Kawaguchi J., Theunissen T. W., Smith A. (2008) PLoS Biol. 6, e253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa M., Koyanagi M., Tanabe K., Takahashi K., Ichisaka T., Aoi T., Okita K., Mochiduki Y., Takizawa N., Yamanaka S. (2008) Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan E. M., Ratanasirintrawoot S., Park I. H., Manos P. D., Loh Y. H., Huo H., Miller J. D., Hartung O., Rho J., Ince T. A., Daley G. Q., Schlaeger T. M. (2009) Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 1033–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markoulaki S., Hanna J., Beard C., Carey B. W., Cheng A. W., Lengner C. J., Dausman J. A., Fu D., Gao Q., Wu S., Cassady J. P., Jaenisch R. (2009) Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 169–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huangfu D., Maehr R., Guo W., Eijkelenboom A., Snitow M., Chen A. E., Melton D. A. (2008) Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 795–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng B., Ng J. H., Heng J. C., Ng H. H. (2009) Cell Stem Cell 4, 301–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi Y., Desponts C., Do J. T., Hahm H. S., Schöler H. R., Ding S. (2008) Cell Stem Cell 3, 568–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esteban M. A., Wang T., Qin B., Yang J., Qin D., Cai J., Li W., Weng Z., Chen J., Ni S., Chen K., Li Y., Liu X., Xu J., Zhang S., Li F., He W., Labuda K., Song Y., Peterbauer A., Wolbank S., Redl H., Zhong M., Cai D., Zeng L., Pei D. (2010) Cell Stem Cell 6, 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Gonzalo F. R., Izpisúa Belmonte J. C. (2008) PLoS One 3, e1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanna J., Saha K., Pando B., van Zon J., Lengner C. J., Creyghton M. P., van Oudenaarden A., Jaenisch R. (2009) Nature 462, 595–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han J., Yuan P., Yang H., Zhang J., Soh B. S., Li P., Lim S. L., Cao S., Tay J., Orlov Y. L., Lufkin T., Ng H. H., Tam W. L., Lim B. (2010) Nature 463, 1096–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Judson R. L., Babiarz J. E., Venere M., Blelloch R. (2009) Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 459–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.