Abstract

Among various DNA damages, double-strand breaks (DSBs) are considered as most deleterious, as they may lead to chromosomal rearrangements and cancer when unrepaired. Nonhomologous DNA end joining (NHEJ) is one of the major DSB repair pathways in higher organisms. A large number of studies on NHEJ are based on in vitro systems using cell-free extracts. In this paper, we summarize the studies on NHEJ performed by various groups in different cell-free repair systems.

1. Introduction

Maintenance of genomic integrity and stability is of prime importance for the survival of an organism. Upon exposure to different damaging agents, DNA acquires various lesions such as base modifications, single-strand breaks (SSBs), and double-strand breaks. Organisms have evolved specific repair pathways in order to efficiently correct such DNA damages. Examples include base excision repair (base level changes), nucleotide excision repair (distortions in the DNA); and single-strand break repair. DSBs are considered as the most deleterious type of DNA damages, among different lesions. It can result in chromosomal rearrangements like translocations and cancer or cell death when unrepaired [1, 2].

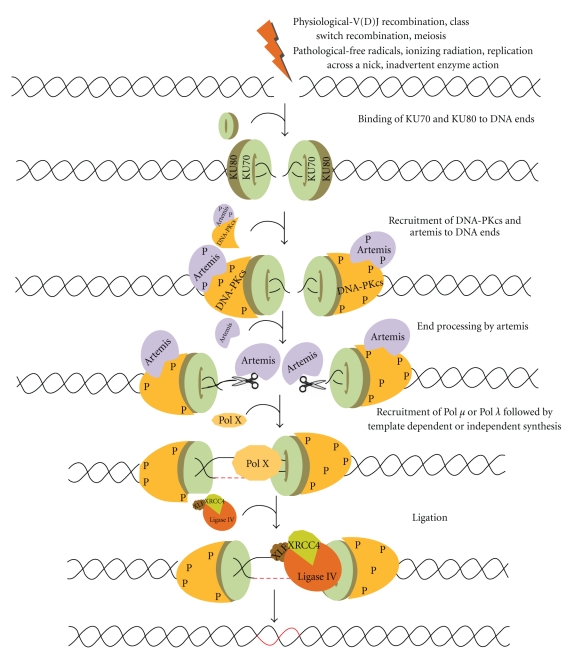

DSBs can be generated by pathological or physiological agents. Pathological agents can be exogenous such as ionizing radiation, or chemotherapeutic agents like bleomycin (Figure 1). They can also be endogenous like oxidative free radicals, replication across a nick, inadvertent enzyme action at fragile sites (Figure 1), mechanical shearing at anaphase bridges, metabolic by products, and so forth [3–5]. Physiological processes such as V(D)J recombination, class switch recombination (CSR); and meiosis also introduce DSBs in our genome.

Figure 1.

Double-strand breaks (DSBs) are generated exogenously by ionizing radiation, or endogenously by free radicals or during V(D)J recombination in pre-B (bone marrow) and pre-T cells (thymus) by RAG complex or also during class switch recombination in activated B cells (in the peripheral lymphoid tissues such as spleen, lymph nodes, and Peyer's patches). NHEJ involves the binding of Ku70 and Ku80 heterodimeric complex to the DNA ends, and DNA-PKcs in association with ARTEMIS. ARTEMIS is a 5′-3′ exonuclease in an unphosphorylated form while it is an endonuclease in a phosphorylated form. Artemis protein acts as an exonuclease and helps in resection of the ends. Polymerase X family members are then recruited for DNA synthesis, which includes both template dependent and independent DNA synthesis. The resulting DNA ends are ligated by a specific DNA LIGASE IV with stimulatory factors (XRCC4-LIGASE IV-XLF complex) that restores the integrity of DNA.

DSB repair pathways in mammals can be broadly classified into two categories, namely, homologous recombination (HR) and nonhomologous DNA end joining. NHEJ needs little or no homology and is usually imprecise, while HR requires a region of extensive homology [6–8]. HR occurs in S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and is accurate as it uses the sister chromatid as a template to repair the damaged strand [8–10]. The protein machinery involved in HR includes RAD50, MRE11, NBS1, RAD51, and RAD54 [6, 11, 12]. On the other hand, NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle and is error prone [4, 10, 13]. The errors introduced during NHEJ in higher eukaryotes pose little threat to the organism as only a small percentage of the genome encodes for proteins whereas entering into S or G2 phase with unrepaired DNA strands is a major risk.

2. NHEJ Proteins

Genetic studies using radiosensitive mammalian cell lines deficient in DSB rejoining in conjunction with biochemical evidences have led to the discovery of many NHEJ proteins. Ku proteins, which play a major role in NHEJ, were originally discovered as a target for autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune diseases [14–16]. Subsequently, studies using various DNA end structures provided the evidence that Ku proteins recognize the DNA ends [17]. The first evidence for the involvement of Ku proteins in NHEJ came from the discovery that Ku80 subunit was defective in X-ray sensitive mammalian cell mutants in the XRCC5 group [18–20]. Ku70 was identified initially as an interaction partner for Ku80 by biochemical assays [16, 21]. Later, in vivo studies confirmed this observation [22]. DNA-PKcs was first identified during a biochemical screen for kinases that were stimulated by double-stranded DNA [17]. Chinese hamster ovary cell lines lacking XRCC7 showed 10-fold higher sensitivity to radiation and later the protein coded by the gene was identified as DNA-PK [16, 23, 24]. The critical finding that Ku protein is the regulatory component of DNA-PKcs unified both areas of research and gave a new dimension to the NHEJ field. The in vivo role of Ku and DNA PKcs was later confirmed by many studies [2, 25–29].

More or less at the same time, a distinct DNA ligase, named DNA Ligase IV, having ATP dependent ligase activity was purified from HeLa cell nuclei with substrate specificity to both single- and double-stranded breaks [30]. Later, the same ligase was identified as the enzyme responsible for NHEJ both in mammals and yeast [31–33]. Another, NHEJ protein, XRCC4 was identified based on radiosensitivity shown by mammalian cells deficient for XRCC4 gene [21, 34–36]. Later using biochemical assays it was reported that XRCC4, small nuclear phosphoprotein, forms a tight, specific complex with DNA Ligase IV and stimulates its activity by many folds [32, 33]. More recently, it was identified that an XRCC4-like protein, XLF (also known as Cernunnos), is an interaction partner of the DNA Ligase IV/XRCC4 complex, facilitating the ligation of the ends [37, 38].

In early 2000, Artemis, a novel protein involved in V(D)J recombination and DSB repair, was identified [39]. It was reported that a mutation in the Artemis was responsible for the SCID phenotype [39]. Later, using an elegant biochemical assay system, it was shown that phosphorylated Artemis in conjunction with DNA-PKcs complex has the ability to cleave the hairpin intermediate of V(D)J recombination, besides its ability to cleave 5′-overhangs, 3′-overhangs, and other DNA structures [40–43]. In addition, Artemis on its own possesses an exonuclease activity [42]. Polymerases involved in NHEJ, Pol μ and Pol λ, both belonging to the polX family were also identified later [44, 45].

3. Mechanism of NHEJ

The key players of NHEJ recognize the broken DNA ends and further process and ligate them [4, 6, 13, 46]. To begin with, the DNA with DSBs is recognised by the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimeric complex, which then recruits DNA-PKcs in association with Artemis [47–49] (Figure 1). DNA-PKcs and Ku complex play an important role in forming a synaptic complex that brings the two DNA ends together and also interacts with the Ku heterodimer. DNA-PKcs further autophosphorylates itself and phosphorylates Artemis as well. Artemis-DNA-PKcs complex can cleave 5′-overhangs and 3′-overhangs while Artemis alone can function as an exonuclease [40–42]. After processing, the ends are filled using Pol μ and Pol λ [44, 45]. Finally, the ends are ligated by XLF:XRCC4:DNA Ligase IV complex [31, 32, 37] (Figure 1). Since NHEJ is not precise, although the integrity is maintained, it may lead to mutations which may further help in evolution of the organism.

4. Alternative NHEJ

In the absence of key NHEJ proteins, a less-characterized pathway has been shown to play an important role in joining of DSBs, which is now classified as alternative NHEJ or backup NHEJ or microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ). Although recent studies indicate that this pathway is distinct and error prone, the exact mechanism is yet to be uncovered. A classic paper which introduced the term alternative NHEJ describes it as a possible source of chromosomal translocation and the authors showed coamplification of c-Myc and IgH locus from pro-B lymphomas in mice deficient for p53 and Xrcc4 [50]. Another interesting study showed a reduced level of class switch recombination and increased number of chromosomal breaks at IgH locus in mouse B cells, which were deficient for XRCC4 and Ligase IV [51]. Another study showed the occurrence of robust alternative end joining in the absence of XRCC4 and upon removal of certain portions of murine RAG proteins [52]. Besides, a residual joining mediated by microhomology towards the end of DSBs was also identified in Xrcc4 defective cells [53]. The protein machinery for this kind of backup joining in the absence of key NHEJ proteins is still not very clear although studies suggest the role of MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex in a subset of alternative NHEJ junctions [54, 55]. Another study has deciphered the role of PARP1 in repairing switch regions through a microhomology-mediated pathway while PARP2 suppresses IgH/c-myc translocations during immunoglobulin class switch recombination [56]. DNA Ligase IIIα and WRN have also been shown to contribute to the repair of DSBs by alternative NHEJ [57]. Therefore, canonical NHEJ requires XRCC4-Ligase IV complex while alternative NHEJ is characterized by joining mediated through microhomology regions, which is prominent in the absence of canonical NHEJ proteins. Recently, an interesting study has shown the role of XRCC4-LigaseIV in suppressing alternative end joining during chromosomal translocations [58]. Another study has shown the role of alternative end joining in robust IgH locus deletions and translocations in the combined absence of Ku70 and LigaseIV [59].

We further discuss NHEJ catalysed by crude extracts which includes joining mediated by classical NHEJ, single-strand annealing, alternative NHEJ, or microhomology-mediated end joining.

5. NHEJ Assays

Since NHEJ is the major pathway of DSB repair in higher organisms, extensive studies have been done to understand its mechanism. Various in vitro and in vivo assays have been designed to study NHEJ in different cell lines, which were derived from different cancers. In this section, we will discuss different types of NHEJ assays used in the literature, so far. Intracellular (ex vivo) assays have been generally based on transfection of mammalian cells with restriction enzyme linearized plasmid DNA [60–62]. Following transfection, cells were allowed to grow for several hours and plasmid DNA was harvested using either alkaline lysis or a high-salt-based nondenaturing method. The NHEJ products were analysed by Southern hybridization. The joining junctions were then characterized by PCR amplification followed by cloning and sequencing. In one of the first studies, the authors' transfected linear SV40 genome with mismatched ends into cultured monkey kidney cells and checked for the presence of recombinants [60, 61, 63]. Some other studies used vectors that overexpress I-SceI endonuclease within the cells to induce DSBs on a plasmid containing I-SceI site, which has an advantage that the DSBs can be induced within the cells [64, 65].

The intracellular assays, although widely used, have many shortcomings. Generally, the quantity of NHEJ products obtained are very low and hence, various end-joined products such as dimer, trimer, and other forms of multimers cannot be visualized on a gel even after Southern hybridization. PCR amplification could be used for detecting the NHEJ products; however, it may not be able to distinguish between different types of joined products. Besides, while extracting DNA out of the cell, many linear products could be lost and hence one would not get the actual efficiency of joining. Nevertheless, it is an excellent system because the role of different proteins can be studied as one could generate knockout for different NHEJ genes in cell lines.

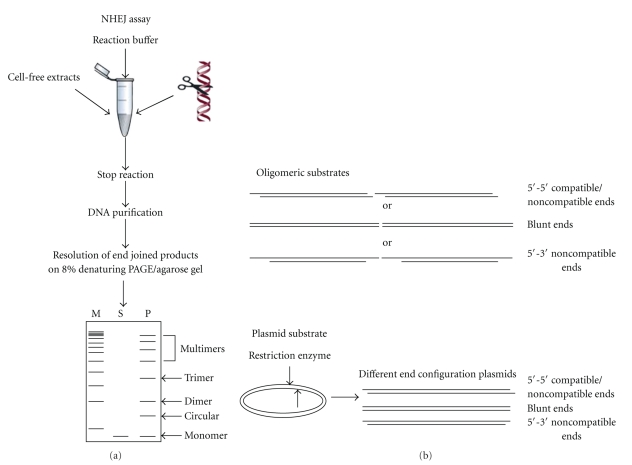

In vitro assays, on the other hand, use a different strategy. They use a cell-free system containing different cellular proteins or selected purified proteins [41, 66–71]. Such assays have been instrumental in studying NHEJ both at the biochemical and molecular level. Cell-free system includes either total protein, cytoplasmic, or nuclear extracts prepared generally from cell lines or rarely from tissues [67–69, 72, 73]. Cell-free system is better because it provides greater flexibility in selecting the types of DSB end configurations. The sequences at or adjacent to DSBs can be easily manipulated to study different junctional features of NHEJ. In vitro assays have used two types of DNA substrates, plasmids and oligomers. Although plasmid substrates are most commonly used, genomic DNA has also been studied [41, 68, 73–76] (Figure 2). DSBs are generated either by restriction enzyme digestion, by treatment with chemicals such as bleomycin, or by irradiation with x-rays or γ-rays [68, 73, 74, 77–79]. The joining products can be visualised on agarose gel following purification of products or after Southern hybridization, depending on the quantity of the substrates used [67, 68, 73, 74]. An oligomer based system has also been used recently for studying NHEJ [41, 76, 80]. In this assay, appropriate oligomers can be designed, synthesized, and annealed to generate substrates containing different DSBs (Figure 2(b)). These substrates can be end-labelled with [γ −32P] ATP, incubated with the extracts or purified proteins, and then resolved on a polyacrylamide gel (Figure 2(a)). In both cases, all the joining products can be visualised and the efficiency of the joining between the substrates can be easily compared as it is proportional to the intensity of bands. The standard NHEJ products observed are dimers, trimers, multimers, and circular products [67, 68, 74]. Similar to intracellular studies, NHEJ junctions can be PCR amplified, cloned, and sequenced. The extent of joining can also be determined by using quantitative PCR [75]. Oligomeric DNA substrates provide more flexibility with respect to end configurations of DSBs as compared to plasmid substrates, where restriction enzyme sites are used to generate DSBs. However, size of the oligomers could be a limiting factor in certain studies.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of NHEJ reaction using cell-free extracts. (a) Cell-free extract is incubated with one of the 5′-end-labelled DNA substrate (oligomer) or restriction enzyme-digested plasmid DNA as shown in the figure along with NHEJ buffer. The reaction is stopped by adding proteinase K and EDTA, DNA is purified by phenol:chloroform extraction, precipitated with glycogen and ethanol, resuspended in TE, and run on 8% denaturing PAGE or agarose gel. After end joining, dimers, trimers, and multimers can be seen. “M” is marker, “S” is substrate, and “P” indicates products. (b) Oligomeric or plasmid DNA substrates

6. Preparation of Cell-Free Extracts from Different Sources

Manley et al. described the protocol for the preparation of cell-free extracts of in vitro cultured cells for the first time [81]. They precipitated the proteins using ammonium sulphate following lysis of the cells using hypotonic buffer and mechanical pressure. Later, many studies adopted modifications to Manley's protocol to prepare cell extracts from different sources. In one of the studies, the concentration of ammonium sulphate was changed in order to reduce the nonspecific nuclease activity present in the extracts [82]. Wood et al. introduced several changes to the cell extract preparation while studying nucleotide excision repair [83]. Later, the protocol was modified to prepare cell-free extracts from tissues (testicular cells) to study DSB repair pathways [68, 84]. Another method of preparation of cell-free extracts involves cellular lysis, followed by removal of cell debris by ultracentrifugation [74]. Although both methods are different in many ways, the overall repair efficiency of the cell-free extracts is similar. One of the major drawbacks of these methods is with respect to the number of cells required for the extract preparation. Both require very high number of cells (>1–5 × 108). In contrast, a recent study has scaled down the number of cells required to 5–10 × 106 [85]. The NHEJ efficiency was found to be optimum after testing in different cell lines including MO59K (glioblastoma), HepG2 (liver), HeLa (cervix), MCF-7 (breast), A549 (lungs), HCT116 (colon), and RT112 (bladder). This microscale assay can be used for clinical samples and thus the role of DNA DSB repair in tumorigenesis can be studied [85].

7. NHEJ Using Different Cell-Free Systems

Many studies have used different cell-free systems to study NHEJ. One of the first studies to report NHEJ in vitro using cell-free extracts was done using fertilized or activated Xenopus eggs. End joining was observed using different plasmid substrates containing DSBs with varying end configurations [71, 86]. NHEJ has also been reported from germinal vesicles (oocyte nuclei) of Xenopus where ligation of compatible ends was tested and the efficiency of joining was compared among different stages of oocyte development. Authors found that interestingly only the stage VI oocytes showed NHEJ, which was in presence of dNTPs. Deletions were also seen at the junctions of the end-joined products [87].

Mammalian cells have been extensively used for in vitro and in vivo end joining reactions. Nuclear extracts from MRC5V1 (immortalised control fibroblasts cell line) were found to catalyze the efficient joining of compatible overhangs as compared to blunt ends [67, 88]. Nuclear extracts from HeLa cells could join linear plasmid substrates, in both head-to-head and tail-to-tail configurations [69]. Another study compared the NHEJ activity of both nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from three human and one mouse cell line. Interestingly, they observed that the extent of deletion and mechanism of joining was similar to Xenopus oocytes [89]. A study using extracts prepared from human lymphoblastoid cell line, GM00558B, described a precise and LIGASE IV-dependent NHEJ on a BamHI digested plasmid DNA. For the first time, authors showed a direct role for Ku70, Ku80, and DNA-PKcs in NHEJ using an in vitro cell-free system [74]. Sequence analysis of NHEJ junctions by another study showed that deletions occur exclusively between short direct repeats in nuclear extracts prepared from AT5BIVA (derived from ATM patient) and MRC5V1 (derived from a normal individual) [88]. SupT1 cells (human T cell lymphoblastic lymphoma) catalyzed efficient joining without deletions or insertions, when complementary ligatable ends were used for the study. However, interestingly, even in the case of noncomplementary ends, the joining took place without deletions [73]. Chinese hamster ovary cell line was used to demonstrate that 125I-Triplex forming oligonucleotide containing radiation-induced DSBs was repaired at approximately 10-fold lower efficiency as compared to restriction enzyme generated DSBs [90].

In an independent study, different cell lines were employed while standardizing the clinical samples for analysing NHEJ and it was observed that the efficiency of NHEJ varied among the cells [85]. Cell-free assay was also used to compare the efficiency of 11 sporadic breast cancer cell lines (BCCLs) with normal fibroblasts and it was found that only 2 BCCLs showed a reduced NHEJ in vitro [91].

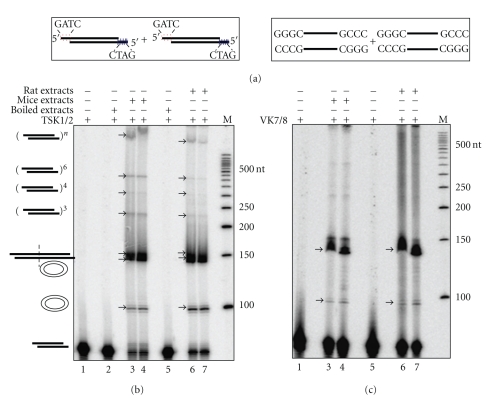

Attempts were also made to study NHEJ in tissues using cell-free extracts. In one of the first studies using a mice testicular cell-free system, it was shown that NHEJ is efficient in male germ cells [68, 84]. Based on plasmid rejoining assay, the authors reported end-joining leading to dimers, trimers, and other forms of multimers, while circularization was absent [68]. The joining of complementary and noncomplementary ends took place with minimum alterations [84]. In continuation to this study, we have recently compared the efficiency of NHEJ in mice and rat testicular extracts, using an oligomer-based assay system. We noticed that there was no major difference in the joining efficacy when mice or rat testicular extracts were used (Figure 3). More recently, we compared the NHEJ efficiencies between testis and other somatic tissues using cell-free extracts. Interestingly, we found that similar to testis, lungs also showed efficient NHEJ (unpublished, SS & SCR). Efficiency of NHEJ was moderate in case of brain, thymus, and spleen while it was weaker in case of kidney, liver, and heart. An independent study showed an efficient NHEJ activity in rat neurons, while it was also shown that efficiency of NHEJ in rat neurons can go down in an age-dependent manner [92, 93]. NHEJ activity of nuclear extracts prepared from cortical neurons of patients suffering from Alzheimer's disease (AD) was also compared with that of normal human subjects and it was reported that DNA-PKcs activity was significantly lower in AD brains when compared to healthy controls [94].

Figure 3.

Comparison of efficiencies of NHEJ in rat and mice testis. Cell-free extract was prepared from age-matched rat and mice testes and protein profile was normalized between both animals. 5 μg of protein was incubated with 4 nM of 5′-end labelled with [γ −32P] DNA containing both compatible and blunt termini against each lane (a) which are represented schematically along with buffer containing 30 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 50 μM dNTPs, and 0.1 μg BSA. End joining reaction using (b) compatible end and (c) blunt end DNA. Lane 1 shows negative control that contains substrate alone, Lane 2 shows heat-inactivated control which is mice testis cell-free extract-boiled for 10 min and used for the reaction, and Lanes 3 and 4 are the end joining reactions with cell-free extract from mice testis. Lane 5 is the heat-inactivated control which is boiled rat testicular extract as described previously. Lanes 6 and 7 are the end joining reactions with rat testicular cell-free extracts. “M” indicates 5′-end-labelled 50 bp ladder. The efficiency of joining is similar in both mice and rat testicular extracts. Different types of end-joined products formed are indicated.

NHEJ activity was also studied in vivo by transfecting adenovirus DNA fragments into A549 (lung carcinoma cell line) and it was found that the joining was efficient irrespective of the ends [72]. Previously, monkey kidney cell lines have been used for studying NHEJ using transfection assays [60, 61, 63, 95]. Thus, the mechanistic aspects of NHEJ have been studied using different cell lines both in vitro and in vivo.

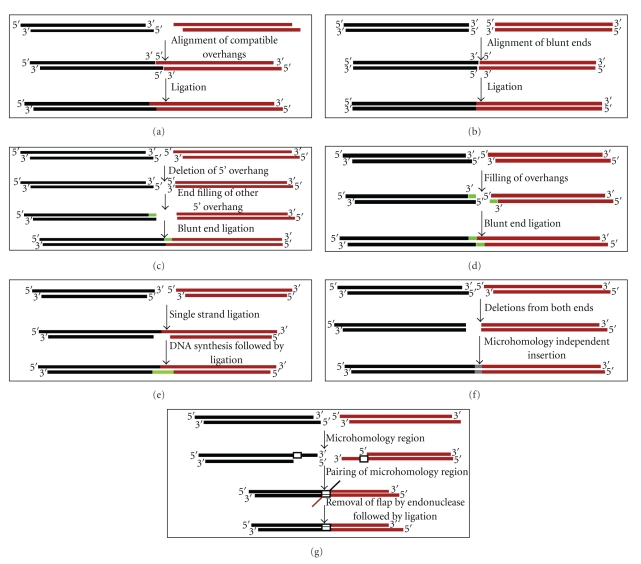

8. NHEJ Mechanisms in Cell-Free System

Various studies described above helped in unravelling the mechanistic aspects of NHEJ (Figure 4). Using monkey kidney cells transfected with SV40 T-antigen containing episome, it was noted that single-strand extensions are stable and few nucleotides present at the terminal end of a DSB are important for the joining [60, 63]. The authors proposed three independent mechanisms for the end-joining based on the sequence at the junctions, which were single-stranded DNA ligation, template-directed ligation, and postrepair ligation [60]. Later, other studies helped in deciphering the fine mechanistic details of NHEJ pathway. If the ends were compatible, joining was predominantly conservative and mostly required only LigaseIV or LigaseIV-XRCC4 complex (Figure 4(a)) [68, 75]. In this case, following the alignment, the ends were simply ligated. However, the involvement of a separate protein for alignment is still not clear. The joining mechanism was mostly the same for DSBs with blunt ends as well (Figure 4(b)). In this case also, the joining generally did not involve any modifications at the junctions, although the efficiency was many fold lower as compared to compatible ends. In case of noncomplementary ends with 5′-5′ overhangs, ligation was dependent on end-filling of one end and deletion of the other (Figure 4(c)) [96]. Alternatively, joining could occur after end-filling of each end independently followed by ligation or joining of one overhang with a second overhang which was end filled (Figure 4(d)) [63]. When DSBs with 5′ and 3′ overhangs were used for the study, a different mechanism was used, in which single-strand ligation of protruding 5′ and 3′ ends occurred initially, followed by template dependent strand synthesis (Figure 4(e)). In an interesting study using Xenopus oocytes cell-extracts as a model system, a novel end alignment mechanism, in which alignment of 3′ protruding ends followed polymerisation and ligation of two DNA ends, was described [86]. During joining of certain noncompatible ends, deletion from both ends followed by blunt end ligation has also been proposed (Figure 4(f)) [60, 71].

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of possible mechanisms involved in repair for DNA termini. (a) In case of compatible ends, ligation usually does not involve much modification. Here, the two termini are aligned and ligated by DNA LIGASE IV. (b) Similarly, alignment of DNA ends in case of blunt ends take place and are ligated by DNA LIGASE IV as it does not need end modifications. On the other hand, modifications take place for non-compatible ends. There are different possibilities in case of 5′-5′ substrate which includes (c) deletion of nucleotides from both ends and insertion of nucleotides followed by ligation or (d) deletion of 5′-overhang from one end, end-filling of other 5′-end followed by blunt end ligation. (e) Another possibility includes end filling of both the overhangs followed by ligation. (f) In case of 5′-3′ overhangs, single strand ligation of overhangs is followed by template dependent synthesis and ligation. (g) Microhomology dependent joining can take place in any of the overhangs which is characterized by pairing of microhomology region followed by removal of flap by an endonuclease and then ligation.

A microhomology-mediated joining has also been reported by different groups irrespective of the termini (Figure 4(g)) [84, 88, 96]. This mechanism involves exonuclease digestion of one of the strands till the microhomology region is exposed, followed by the alignment of microhomology sequence. The flap region is deleted by Artemis/DNAPKcs or FEN endonuclease. Template dependent DNA synthesis takes place and nicks are then ligated by using LigaseIV complex [75]. Recent studies have suggested that in case of classical NHEJ, the microhomology box normally consists of 1–4 nucleotides [97]. If the size of microhomology used is more than 6–8 nucleotides, the joining is categorised as an alternative NHEJ as discussed above, which is proposed as the repair mechanism involved in the generation of many chromosomal translocations [51, 97].

9. Future Prospects

Numerous studies have utilized cell lines as a model system to understand the mechanism of NHEJ. Cell lines give an opportunity to study NHEJ at intracellular level. In addition, cell lines grow much faster than the original tissues from where they are derived. Therefore, it is difficult to extrapolate these findings to the in vivo scenario, where most of the cells of somatic tissues do not grow actively. It has been shown that glioma cell lines possess lower DNA repair capacity compared to the ascitic fluid collected from tumour [98]. Moreover, studies have also shown that expression of proteins in a cell line is different from that of the tissue of its origin [99]. Besides, cell lines are derived from tumour tissues and, therefore, their origin itself is controversial as most of the tumours are metastatic [100]. Therefore, studies using primary tissues to understand the mechanism of NHEJ are important in the coming years.

It is known that tissues of various origins have differential sensitivity towards radiation. It appears that there could be a correlation between radiosensitivity and the rate of cell division. The tissues with replicating cells, such as blood, testis, bone marrow, ovaries, and intestine, are highly sensitive, while others are less radiosensitive [101, 102]. γ-H2AX formation could be correlated with radiosensitivity in complex tissues, however, this requires more investigation. Studies on NHEJ and the recently discovered alternative NHEJ, at the tissue level could help in understanding the mechanism of radiosensitivity and susceptibility to cancer in complex tissues and organs.

Although end-alignment issues related to NHEJ have been studied extensively, still many questions are unanswered. Identification of novel proteins in NHEJ may help facilitate addressing such questions. The signalling which follows DNA damage could be another area of interest in the context of human diseases.

Conflict of Interest

Authors disclose that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mridula Nambiar, Nishana M. and other members of SCR laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. to “This work was supported by grant from DAE, India (2008/37/5/BRNS) and IISc start-up grant for S. C. Raghavan, S. Sharma acknowledges SRF from DBT, India.

References

- 1.Lieber MR, Yu K, Raghavan SC. Roles of nonhomologous DNA end joining, V(D)J recombination, and class switch recombination in chromosomal translocations. DNA Repair. 2006;5(9-10):1234–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson DO, Alt FW. DNA double strand break repair and chromosomal translocation: lessons from animal models. Oncogene. 2001;20(40):5572–5579. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hefferin ML, Tomkinson AE. Mechanism of DNA double-strand break repair by non-homologous end joining. DNA Repair. 2005;4(6):639–648. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weterings E, Chen DJ. The endless tale of non-homologous end-joining. Cell Research. 2008;18(1):114–124. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyman C, Kanaar R. DNA double-strand break repair: all’s well that ends well. Annual Review of Genetics. 2006;40:363–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson SP. Sensing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(5):687–696. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takata M, Sasaki MS, Sonoda E, et al. Homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways of DNA double-strand break repair have overlapping roles in the maintenance of chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells. EMBO Journal. 1998;17(18):5497–5508. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonoda E, Sasaki MS, Buerstedde J-M, et al. Rad51-deficient vertebrate cells accumulate chromosomal breaks prior to cell death. EMBO Journal. 1998;17(2):598–608. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieber MR, Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4(9):712–720. doi: 10.1038/nrm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartlerode AJ, Scully R. Mechanisms of double-strand break repair in somatic mammalian cells. Biochemical Journal. 2009;423(2):157–168. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West SC. Molecular views of recombination proteins and their control. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4(6):435–445. doi: 10.1038/nrm1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiruvella KK, Sankaran SK, Singh M, Nambiar M, Raghavan SC. Mechanism of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. The ICFAI Journal of Biotechnology. 2007;1:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeves WH. Use of monoclonal antibodies for the characterization of novel DNA-binding proteins recognized by human autoimmune sera. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1985;161(1):18–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mimori T, Hardin JA, Steitz JA. Characterization of the DNA-binding protein antigen Ku recognized by autoantibodies from patients with rheumatic disorders. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261(5):2274–2278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dynan WS, Yoo S. Interaction of Ku protein and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit with nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Research. 1998;26(7):1551–1559. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker AI, Hunt T, Jackson RJ, Anderson CW. Double-stranded DNA induces the phosphorylation of several proteins including the 90 000 mol. wt. heat-shock protein in animal cell extracts. EMBO Journal. 1985;4(1):139–145. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb02328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smider V, Rathmell WK, Lieber MR, Chu G. Restoration of X-ray resistance and V(D)J recombination in mutant cells by Ku cDNA. Science. 1994;266(5183):288–291. doi: 10.1126/science.7939667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taccioli GE, Gottlieb TM, Blunt T, et al. Ku80: product of the XRCC5 gene and its role in DNA repair and V(D)J recombination. Science. 1994;265(5177):1442–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.8073286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rathmell WK, Chu G. Involvement of the Ku autoantigen in the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(16):7623–7627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeggo PA. DNA-PK: at the cross-roads of biochemistry and genetics. Mutation Research. 1997;384(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu Y, Jin S, Gao Y, Weaver DT, Alt FW. Ku70-deficient embryonic stem cells have increased ionizing radiosensitivity, defective DNA end-binding activity, and inability to support V(D)J recombination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(15):8076–8081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lees-Miller SP, Godbout R, Chan DW, et al. Absence of p350 subunit of DNA-activated protein kinase from a radiosensitive human cell line. Science. 1995;267(5201):1183–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.7855602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan DW, Lees-Miller SP. The DNA-dependent protein kinase is inactivated by autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(15):8936–8941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rooney S, Sekiguchi J, Zhu C, et al. Leaky Scid phenotype associated with defective V(D)J coding end processing in Artemis-deficient mice. Molecular Cell. 2002;10(6):1379–1390. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blunt T, Finnie NJ, Taccioli GE, et al. Defective DNA-dependent protein kinase activity is linked to V(D)J recombination and DNA repair defects associated with the murine scid mutation. Cell. 1995;80(5):813–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karanjawala ZE, Adachi N, Irvine RA, et al. The embryonic lethality in DNA ligase IV-deficient mice is rescued by deletion of Ku: implications for unifying the heterogeneous phenotypes of NHEJ mutants. DNA Repair. 2002;1(12):1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu C, Bogue MA, Lim D-S, Hasty P, Roth DB. Ku86-deficient mice exhibit severe combined immunodeficiency and defective processing of V(D)J recombination intermediates. Cell. 1996;86(3):379–389. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frank KM, Sharpless NE, Gao Y, et al. DNA ligase IV deficiency in mice leads to defective neurogenesis and embryonic lethality via the p53 pathway. Molecular Cell. 2000;5(6):993–1002. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robins P, Lindahl T. DNA ligase IV from HeLa cell nuclei. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(39):24257–24261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson TE, Grawunder U, Lieber MR. Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates non-homologous DNA end joining. Nature. 1997;388(6641):495–498. doi: 10.1038/41365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grawunder U, Wilm M, Wu X, et al. Activity of DNA ligase IV stimulated by complex formation with XRCC4 protein in mammalian cells. Nature. 1997;388(6641):492–495. doi: 10.1038/41358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Critchlow SE, Bowater RP, Jackson SP. Mammalian DNA double-strand break repair protein XRCC4 interacts with DNA ligase IV. Current Biology. 1997;7(8):588–598. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson LH, Jeggo PA. Nomenclature of human genes involved in ionizing radiation sensitivity. Mutation Research. 1995;337(2):131–134. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00018-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeggo PA, Tesmer J, Chen DJ. Genetic analysis of ionising radiation sensitive mutants of cultured mammalian cell lines. Mutation Research. 1991;254(2):125–133. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thacker J, Wilkinson RE. The genetic basis of resistance to ionising radiation damage in cultured mammalian cells. Mutation Research. 1991;254(2):135–142. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahnesorg P, Smith P, Jackson SP. XLF interacts with the XRCC4-DNA Ligase IV complex to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Cell. 2006;124(2):301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buck D, Malivert L, de Chasseval R, et al. Cernunnos, a novel nonhomologous end-joining factor, is mutated in human immunodeficiency with microcephaly. Cell. 2006;124(2):287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moshous D, Callebaut I, de Chasseval R, et al. Artemis, a novel DNA double-strand break repair/V(D)J recombination protein, is mutated in human severe combined immune deficiency. Cell. 2001;105(2):177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002;108(6):781–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma Y, Lu H, Tippin B, et al. A biochemically defined system for mammalian nonhomologous DNA end joining. Molecular Cell. 2004;16(5):701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma Y, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. The Artemis:DNA-PKcs endonuclease cleaves DNA loops, flaps, and gaps. DNA Repair. 2005;4(7):845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yannone SM, Khan IS, Zhou R-Z, Zhou T, Valerie K, Povirk LF. Coordinate 5’ and 3’ endonucleolytic trimming of terminally blocked blunt DNA double-strand break ends by Artemis nuclease and DNA-dependent protein kinase. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36(10):3354–3365. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tseng H-M, Tomkinson AE. A physical and functional interaction between yeast Pol4 and Dnl4-Lif1 links DNA synthesis and ligation in nonhomologous end joining. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(47):45630–45637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahajan KN, Nick McElhinny SA, Mitchell BS, Ramsden DA. Association of DNA polymerase μ (pol μ) with Ku and ligase IV: Role for pol μ in end-joining double-strand break repair. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22(14):5194–5202. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5194-5202.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lieber MR, Lu H, Gu J, Schwarz K. Flexibility in the order of action and in the enzymology of the nuclease, polymerases, and ligase of vertebrate non-homologous DNA end joining: relevance to cancer, aging, and the immune system. Cell Research. 2008;18(1):125–133. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.West RB, Yaneva M, Lieber MR. Productive and nonproductive complexes of Ku and DNA-dependent protein kinase at DNA termini. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1998;18(10):5908–5920. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Falzon M, Fewell JW, Kuff EL. EBP-80, a transcription factor closely resembling the human autoantigen Ku, recognizes single- to double-strand transitions in DNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(14):10546–10552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mimori T, Hardin JA. Mechanism of interaction between Ku protein and DNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261(22):10375–10379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu C, Mills KD, Ferguson DO, et al. Unrepaired DNA breaks in p53-deficient cells lead to oncogenic gene amplification subsequent to translocations. Cell. 2002;109(7):811–821. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan CT, Boboila C, Souza EK, et al. IgH class switching and translocations use a robust non-classical end-joining pathway. Nature. 2007;449(7161):478–482. doi: 10.1038/nature06020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corneo B, Wendland RL, Deriano L, et al. Rag mutations reveal robust alternative end joining. Nature. 2007;449(7161):483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature06168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guirouilh-Barbat J, Rass E, Plo I, Bertrand P, Lopez BS. Defects in XRCC4 and KU80 differentially affect the joining of distal nonhomologous ends. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(52):20902–20907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708541104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dinkelmann M, Spehalski E, Stoneham T, et al. Multiple functions of MRN in end-joining pathways during isotype class switching. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2009;16(8):808–813. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deriano L, Stracker TH, Baker A, Petrini JHJ, Roth DB. Roles for NBS1 in alternative nonhomologous end-joining of V(D)J recombination intermediates. Molecular Cell. 2009;34(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robert I, Dantzer F, Reina-San-Martin B. Parp1 facilitates alternative NHEJ, whereas Parp2 suppresses IgH/c-myc translocations during immunoglobulin class switch recombination. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206(5):1047–1056. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sallmyr A, Tomkinson AE, Rassool FV. Up-regulation of WRN and DNA ligase lll{alpha} in chronic myeloid leukemia: consequences for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Blood. 2008;112(4):1413–1423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simsek D, Jasin M. Alternative end-joining is suppressed by the canonical NHEJ component Xrcc4-ligase IV during chromosomal translocation formation. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2010;17(4):410–416. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boboila C, Jankovic M, Yan CT, et al. Alternative end-joining catalyzes robust IgH locus deletions and translocations in the combined absence of ligase 4 and Ku70. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(7):3034–3039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915067107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roth DB, Wilson JH. Nonhomologous recombination in mammalian cells: role for short sequence homologies in the joining reaction. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1986;6(12):4295–4304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roth DB, Wilson JH. Relative rates of homologous and nonhomologous recombination in transfected DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82(10):3355–3359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grawunder U, Zimmer D, Fugmann S, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. DNA ligase IV is essential for V(D)J recombination and DNA double-strand break repair in human precursor lymphocytes. Molecular Cell. 1998;2(4):477–484. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roth DB, Porter TN, Wilson JH. Mechanisms of nonhomologous recombination in mammalian cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1985;5(10):2599–2607. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.10.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Honma M, Sakuraba M, Koizumi T, Takashima Y, Sakamoto H, Hayashi M. Non-homologous end-joining for repairing I-SceI-induced DNA double strand breaks in human cells. DNA Repair. 2007;6(6):781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willers H, Husson J, Lee LW, et al. Distinct mechanisms of nonhomologous end joining in the repair of site-directed chromosomal breaks with noncomplementary and complementary ends. Radiation Research. 2006;166(4):567–574. doi: 10.1667/RR0524.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thacker J. The role of homologous recombination processes in the repair of severe forms of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Biochimie. 1999;81(1-2):77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.North P, Ganesh A, Thacker J. The rejoining of double-strand breaks in DNA by human cell extracts. Nucleic Acids Research. 1990;18(21):6205–6210. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sathees CR, Raman MJ. Mouse testicular extracts process DNA double-strand breaks efficiently by DNA end-to-end joining. Mutation Research. 1999;433(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nicolas AL, Young CSH. Characterization of DNA end joining in a mammalian cell nuclear extract: junction formation is accompanied by nucleotide loss, which is limited and uniform but not site specific. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1994;14(1):170–180. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pont-Kingdon G, Dawson RJ, Carroll D. Intermediates in extrachromosomal homologous recombination in Xenopus laevis oocytes: characterization by electron microscopy. EMBO Journal. 1993;12(1):23–34. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pfeiffer P, Vielmetter W. Joining of nonhomologous DNA double strand breaks in vitro. Nucleic Acids Research. 1988;16(3):907–924. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Derbyshire MK, Epstein LH, Young CSH, Munz PL, Fishel R. Nonhomologous recombination in human cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1994;14(1):156–169. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bøe S-O, Sodroski J, Helland DE, Farnet CM. DNA end-joining in extracts from human cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;215(3):987–993. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baumann P, West SC. DNA end-joining catalyzed by human cell-free extracts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(24):14066–14070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Budman J, Chu G. Processing of DNA for nonhomologous end-joining by cell-free extract. EMBO Journal. 2005;24(4):849–860. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gu J, Lu H, Tippin B, Shimazaki N, Goodman MF, Lieber MR. XRCC4:DNA ligase IV can ligate incompatible DNA ends and can ligate across gaps. EMBO Journal. 2007;26(4):1010–1023. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Labhart P. Nonhomologous DNA end joining in cell-free systems. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1999;265(3):849–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manova V, Gecheff K, Stoilov L. Efficient repair of bleomycin-induced double-strand breaks in barley ribosomal genes. Mutation Research. 2006;601(1-2):179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pastwa E, Neumann RD, Winters TA. In vitro repair of complex unligatable oxidatively induced DNA double-strand breaks by human cell extracts. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29(16):p. E78. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.16.e78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sharma S, Choudhary B, Raghavan SC. Efficiency of nonhomologous DNA end joining varies among somatic tissues, despite similarity in mechanism. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0472-x. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manley JL, Fire A, Cano A, Sharp PA, Gefter ML. DNA-dependent transcription of adenovirus genes in a soluble whole-cell extract. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1980;77(7):3855–3859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Coudoré F, Calsou P, Salles B. DNA repair activity in protein extracts from rat tissues. FEBS Letters. 1997;414(3):581–584. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wood RD, Robins P, Lindahl T. Complementation of the xeroderma pigmentosum DNA repair defect in cell-free extracts. Cell. 1988;53(1):97–106. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Raghavan SC, Raman MJ. Nonhomologous end joining of complementary and noncomplementary DNA termini in mouse testicular extracts. DNA Repair. 2004;3(10):1297–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Diggle CP, Bentley J, Kiltie AE. Development of a rapid, small-scale DNA repair assay for use on clinical samples. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31(15):p. e83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thode S, Schafer A, Pfeiffer P, Vielmetter W. A novel pathway of DNA end-to-end joining. Cell. 1990;60(6):921–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90340-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lehman CW, Clemens M, Worthylake DK, Trautman JK, Carroll D. Homologous and illegitimate recombination in developing Xenopus oocytes and eggs. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1993;13(11):6897–6906. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.6897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thacker J, Chalk J, Ganesh A, North P. A mechanism for deletion formation in DNA by human cell extracts: the involvement of short sequence repeats. Nucleic Acids Research. 1992;20(23):6183–6188. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.23.6183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Daza P, Reichenberger S, Göttlich B, Hagmann M, Feldmann E, Pfeiffer P. Mechanisms of nonhomologous DNA end-joining in frogs, mice and men. Biological Chemistry. 1996;377(12):775–786. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1996.377.12.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Odersky A, Panyutin IV, Panyutin IG, et al. Repair of sequence-specific 125I-induced double-strand breaks by nonhomologous DNA end joining in mammalian cell-free extracts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(14):11756–11764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mérel P, Prieur A, Pfeiffer P, Delattre O. Absence of major defects in non-homologous DNA end joining in human breast cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2002;21(36):5654–5659. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ren K, Peña de Ortiz S. Non-homologous DNA end joining in the mature rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;80(6):949–959. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vyjayanti VN, Rao KS. DNA double strand break repair in brain: reduced NHEJ activity in aging rat neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;393(1):18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shackelford DA. DNA end joining activity is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006;27(4):596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roth DB, Wilson JH, editors. Genetic Recombination. Washington, DC, USA: American Society for Microbiology; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mason RM, Thacker J, Fairman MP. The joining of non-complementary DNA double-strand breaks by mammalian extracts. Nucleic Acids Research. 1996;24(24):4946–4953. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McVey M, Lee SE. MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director’s cut): deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends in Genetics. 2008;24(11):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Short SC, Martindale C, Bourne S, Brand G, Woodcock M, Johnston P. DNA repair after irradiation in glioma cells and normal human astrocytes. Neuro-Oncology. 2007;9(4):404–411. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carlomagno F, Burnet NG, Turesson I, et al. Comparison of DNA repair protein expression and activities between human fibroblast cell lines with different radiosensitivities. International Journal of Cancer. 2000;85(6):845–849. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000315)85:6<845::aid-ijc18>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sandberg R, Ernberg I. Assessment of tumor characteristic gene expression in cell lines using a tissue similarity index (TSI) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(6):2052–2057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408105102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bentzen SM. Preventing or reducing late side effects of radiation therapy: radiobiology meets molecular pathology. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(9):702–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hall EJ, Giacca AJ. Clinical Responses of Normal Tissues. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]