Abstract

Background

Pregnancy and the postpartum period have been suggested as important contributors to overweight and obesity among women. This paper presents the design, rationale, and baseline participant characteristics of a randomized controlled intervention trial to enhance weight loss in postpartum women who entered pregnancy overweight or obese.

Methods

Active Mothers Postpartum (AMP) is based on the rationale that the birth of a child can be a teachable moment. AMP's primary objectives are to promote and sustain a reduction in body mass index (BMI) up to 2 years postpartum via changes in diet and exercise behavior, with a secondary aim to assess racial differences in these outcomes. Women in the intervention arm participate in ten physical activity group sessions, eight healthy eating classes, and six telephone counseling sessions over a 9-month period. They also receive motivational tools, including a workbook with recipes and exercises, a pedometer, and a sport stroller.

Results

Four hundred fifty women aged ≥18 (mean 30.9), with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (mean 33.0) at baseline (6 weeks postpartum) were enrolled; 45% of the final sample are black and 53% are white. Baseline characteristics by study arm and by race are presented.

Conclusions

Our intervention is designed to be disseminated broadly to benefit the public health. Behavior change interventions based on principles of social cognitive theory, stage of readiness, and other models that coincide with a teachable moment, such as the birth of a child, could be important motivators for postpartum weight loss.

Introduction

Pregnancy-related weight gain and obesity

Pregnancy is a potential contributing factor to overweight and obesity among women.1–3 Up to 20% of postpartum women are 11–14 pounds heavier 6–18 months postpartum than they were before the pregnancy.4 In a Swedish study, 40%–50% of obese women believed their obesity began as a result of pregnancy,5 and 73% had retained more than 10 kg after a pregnancy.6

Women who enter pregnancy overweight or obese are at greatest risk of retaining weight at 12 months postpartum.7 In one study, weight loss trajectories of overweight women were comparable to those of normal weight women in the first 6 months postpartum. However, overweight women were significantly less likely to continue losing weight and had gained weight 6–12 months postpartum while normal weight women had continued to lose.7 There is increasing evidence that postpartum weight retention is associated with race: black women appear to be twice as likely as white women to retain weight postpartum,8 a difference not accounted for by socioeconomic status9 or prepregnancy weight.10–12

Behavioral factors postpartum also contribute to weight retention. In the Stockholm Pregnancy and Weight Study, body weight changes were more strongly associated with postpartum lifestyle factors than with prepregnancy characteristics, such as body weight. Women who retained more weight 1 year postpartum were less likely to report regular meals and exercise and reported more between-meal snacking.13–15 Accordingly, interventions for weight loss that address such behavioral factors have been shown to affect short-term weight loss in the general population and are also likely to be of use postpartum women.16,17

The Cochrane Collaboration has published a review of postpartum weight loss interventions including physical activity and diet change.18 The review included six studies including a total of 245 women. Preliminary evidence from this review suggests that dieting and exercise together appear to be more effective than diet alone in helping women to lose weight after childbirth, but the review concludes that additional studies, with larger sample sizes, are required to confirm the effectiveness and safety of such interventions.

Postpartum transition as teachable moment to promote weight loss

The transition from pregnancy to postpartum could significantly impact three psychological domains suggested to characterize a teachable moment (TM).19 The TM heuristic posits that health events and life transitions that jointly (1) increase perceptions of vulnerability to health risks, (2) prompt concordant emotional responses, and (3) impact self-concept may offer a powerful motivational context for promoting behavior change. The TM concept is appealing because timing formal interventions to coincide with these naturally occurring events might increase the efficacy of lower-intensity interventions, which are best suited for widespread dissemination.

The transition from pregnancy to postpartum may be a TM for encouraging weight loss for several reasons. First, a sizable proportion of women gain more weight than they expected during pregnancy and may view themselves at considerable risk of retaining the weight in the long term. Subsequently, the natural weight loss that occurs in the days and weeks postdelivery could boost women's self-confidence in their ability to lose weight and could be capitalized on by a formal weight loss intervention. Second, hormonal changes could prompt heightened emotionality, which in turn could lead to comfort eating and sedentariness. Finally, the demands of caring for an infant and perhaps other children may also make meal planning and time management difficult. Formal interventions that build skills related to dietary practices and physical activity, increase motivation for change, and boost self-confidence could be attractive to postpartum women who would not otherwise consider formal weight loss interventions.

Materials and Methods

Study design and objectives

This paper presents the design, rationale, and baseline participant characteristics of Active Mothers Postpartum (AMP), a randomized controlled behavioral intervention trial to enhance weight loss in postpartum women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy. The goals of the trial are to facilitate the loss of retained pregnancy weight to prevent future obesity, to encourage the lifestyle changes that will lead to postpartum weight loss, and to assess whether the postpartum period can be a TM for interventions that promote weight loss and healthy weight maintenance through the adoption of weight-related lifestyle changes. A secondary aim is to assess these outcomes for racial differences.

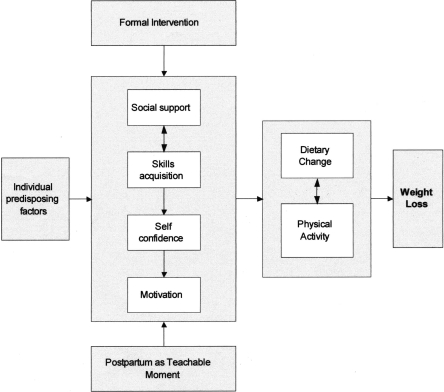

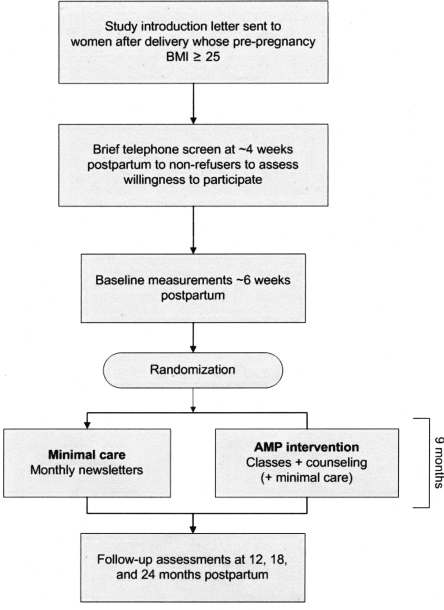

The intervention components for this study are based on principles of social cognitive theory,20 stage of readiness,22 and motivation models. The key assumptions are (1) behavior change is motivated by feelings of self-efficacy, which are enhanced when individuals have the necessary skills to make lifestyle changes, (2) ongoing support can increase self-efficacy and enhance the acquisition of skills needed to sustain behavior change, and (3) motivation and goal setting elicited directly from the participant via motivational interviewing are most conducive to successful behavior change.22 Figure 1 provides a conceptual overview of the study, and Figure 2 provides an overview of the study design.

FIG. 1.

Conceptual model.

FIG. 2.

Study design.

In preparation for the study we administered a survey to overweight and obese postpartum women, gauging their interest in and desire for a lifestyle intervention in this period and assessing the optimal scope, content, and delivery mechanism for such a program. This feasibility study concluded that, indeed, women are receptive to interventions for physical activity and dietary change in the initial months postpartum.23 Intervention materials were also pilot tested with 10 postpartum women (who were not part of the study), and feedback from both the survey and the women in the pilot guided the overall development of the intervention.

Study population and recruitment

Four hundred fifty women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy were enrolled between September 2004 and April 2006. Women were recruited from the three largest obstetrics clinics in the Durham, North Carolina, area and through posters, featuring an 800 number, in such public areas as grocery stores, the smaller obstetrics clinics, and libraries.

Regular prenatal patients at the participating clinics who had experienced a live birth were reviewed weekly by each clinic's staff. Women determined from their medical record to be aged ≥18 and have been overweight or obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25 kg/m2) before pregnancy were sent an introductory letter via priority mail, on their clinic letterhead and signed by the lead physician of their clinic, that described the study. If age and prepregnancy weight data were not available, the woman was sent a letter, and these elements were determined during the telephone screen. Women were offered a toll-free number to decline participation. After 7–10 days, they were contacted for a screening survey.

Following a description of the study and verbal consent for the survey, a brief set of questions was administered to assess eligibility. Inclusion criteria were kept as broad as possible; only women who did not speak English, were < age 18, or had any health conditions that prevented them from walking a mile unassisted (consistent with Wing and Jeffery24) were excluded.

If a woman was eligible and interested in the study, a member of the study staff arranged to meet her at her 6-week postpartum obstetrics appointment and obtained measured height and weight using a Seca portable stadiometer and Tanita BWB-800 scale. If the measured BMI was ≥25, the participant was considered eligible, and written informed consent for participation in the intervention trial was obtained. Women were also asked for permission to review their medical chart to obtain information about any medical conditions that might preclude them from participating. From data abstracted from this chart review, the study physician confirmed eligibility or exclusion.

Randomization

Women completed baseline assessments after signing the written consent form but prior to randomization. These assessments were administered by telephone and included a survey of demographics, psychosocial variables, current weight-related behaviors (conducted by a contracted survey firm), and two 24-hour dietary recall interviews (conducted by the Nutrition Laboratory at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro). Once the baseline assessments were complete, women were enrolled in the study and randomized 1:1 to the intervention or control arms (stratified black vs. other and primiparous vs. multiparous) using a block randomization procedure. Participants were contacted by letter and phone to receive their arm assignment, compensation for completing the baseline surveys, and, in the case of intervention participants, information about upcoming classes and their first telephone counseling session.

To obtain a final sample size of 450, 2821 deliveries were reviewed during the recruitment period, of which we were unable to reach 897 for screening, 1262 did not meet inclusion criteria, 148 refused to complete the screening process. Of the 514 who were eligible and consented to participate, 64 failed to complete the baseline assessments. We did not oversample or set specific recruitment goals based on race, but randomization was stratified to ensure appropriate balance by race across the study arms. All recruitment and enrollment procedures were approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

The primary objectives of the intervention are to promote and sustain a 10% reduction in BMI through the late postpartum period via changes in diet and exercise behavior, including reduction of calorie intake, reduction of calories from fat, increased fruit and vegetable consumption, and moderate physical activity 30 minutes per day at least 5 days a week.

Minimal care arm

Women randomized to the control arm receive a biweekly newsletter with topics of interest to new mothers and monetary rewards for completing the three follow-up surveys.

AMP intervention

In addition to the components in the minimal care arm, women in the AMP intervention arm are asked to participate in 10 physical activity group sessions (ACTIVMOMS classes), eight healthy eating classes (Mom's Time Out [MTO] sessions), and six telephone counseling sessions over the 9-month intervention period. The women in this group are provided with a study notebook with exercises, recipes, and other intervention-related information, a sport stroller, and a pedometer. The sport stroller is introduced when the infant is able to support the head (6 months postpartum), approximately halfway through the intervention period, thereby helping to ensure sustained interest in the AMP program. The intervention components are designed to enhance the sustainability of healthy behavior changes beyond the intervention period.

ACTIVMOMS classes

The exercise intervention is in the form of a structured physical activity class built on the established postpartum exercise program at the Duke Center for Living (CFL). Women are strongly encouraged to attend 10 ACTIVMOMS physical activity classes over the 9-month intervention period. Instructors teach participants to develop a sustainable plan to be moderately physically active 30 minutes per day at least 5 days per week. The ACTIVMOMS sessions include specific exercises designed to enhance recovery from pregnancy-related changes in body structure and function, including aerobic, strength, flexibility, and pelvic floor exercises. Using a stroller or a front-facing baby carrier, ACTIVMOMS classes enable mothers to exercise with their babies in a Mom-and-Tot format, but this is not required. The classes are taught by certified postpartum exercise instructors and are small (four or five mother-infant pairs), providing women with individual attention. ACTIVMOMS classes are offered two to six times a week, including Saturdays and different times of day, to accommodate various schedules of both working and stay-at-home mothers. Barriers to exercise and physical activity shared by all new mothers are emphasized and discussed as a group.

Mom's Time Out sessions

The diet intervention is in the format of interactive, educational sessions referred to as Mom's Time Out (MTO). Several MTO sessions are offered each month at convenient times, usually adjacent to the ACTIVMOMS classes. Educational activities help women develop strategies to overcome common barriers to weight loss in the postpartum period, such as lack of time, energy, and motivation.25 Women are taught practical skills shown to facilitate weight loss,26 including making food choices that decrease consumption of high-fat, high-sugar snack foods and beverages (such as soft drinks and sweet iced tea); learning appropriate portion sizes; cooking easy low-fat meals; making appropriate meal choices at fast-food restaurants; and avoiding overeating in stressful situations. During each class, using portable kitchen equipment (an electric frying pan, crockpot), women participate in preparing and sharing a healthy recipe to gain hands-on skills for healthier meal preparation and eating behaviors. Two sessions are in the form of field trips—to the food court at the local mall and to the grocery store—to learn how to shop for low-cost, nutritious foods. Women also gain skills related to developing structured meal plans and grocery lists, scheduling regular meals to reduce between-meal snacking, slowing the pace of eating, and identifying cues of fullness.

Telephone counseling

Every 6 weeks, women in the intervention group receive one of six motivational interviewing sessions from a trained counselor, lasting about 20 minutes each. These sessions are delivered primarily over the phone but occasionally in person (e.g., when the woman comes to the study office to receive her stroller). These calls are adapted to each woman's situation and goals. Consistent with the principles of Motivational Interviewing,22,27,28 the counselor uses reflective listening techniques, self-motivational statements, and change talk to meet the primary objectives of the sessions, which are to elicit women's personal goals for weight loss, discuss barriers and troubleshoot ways to get around them, and encourage attendance at ACTIVMOMS and MTO sessions. Interviewing is guided by a standardized protocol but is flexible such that participants' needs can drive the content of the calls.

Workbook

Along with other fitness-related items (pedometer, water bottle, resistance band), a workbook (loose-leaf binder) is provided to women in the intervention arm. The workbook is intended to be a take-home reference that summarizes MTO and ACTIVMOMS class content. The workbook contains recipes, written descriptions and pictures of postpartum exercises, and other handouts to encourage healthy eating and physical activity, as well as educational material provided as part of the group sessions. The workbook was usually delivered at the first MTO session; in the case of women who did not attend classes initially, the workbook was mailed after 3 months in order to (1) deliver an intervention component to nonattenders and (2) encourage future attendance.

Measures

Table 1 provides an overview of the measures used in the study.

Table 1.

Overview of Measures Collected

| Measures | Chart screen 2 weeks postpartum | Phone screen 4 weeks postpartum | Baseline 6 weeks postpartum | 1 month postintervention 12 months postpartum | 6 months postintervention 18 months postpartum | 12 months postintervention 24 months postpartum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and health-related (predisposing) factors | X | X | X | |||

| Teachable moment factors | X | |||||

| Intervention participation | X | |||||

| Nutrition Data System (NDS) | X | X | ||||

| Brief food frequency questions | X | X | X | X | ||

| 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (PAR) | X | X | ||||

| Brief physical activity questionsa | X | X | X | X | ||

| Measured weight and height | X | X | X | X |

Brief physical activity questions are taken from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).33

Demographic and health-related (predisposing) factors

Basic demographic and social measures were collected at baseline. These included such items as age, race, and education; child care arrangements; and plans to work outside home. Pregnancy and heath-related factors collected at baseline included measured BMI, parity, weight gained during pregnancy, and duration and amount of breastfeeding.13 Participants were asked about their overall health status and if they had any “longstanding illness or medical condition.” Smoking status was assessed, and a brief scale indicating problems with incontinence29 was administered. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)30 was also administered; any participant reporting suicidal thoughts was followed up by phone by the study physician to assess the need for referral.

Teachable Moment factors

At baseline, we assessed the affect and risk perceptions of women dealing with issues of weight change in the immediate postpartum period. To assess weight-related affect, items from the positive and negative affect scale (PANAS)31 with face validity for relevance to feelings about weight loss were used. Weight-related risk perceptions, perceived comparative risk for health outcomes, and perceived conditional health risks were also rated, as were global and weight-related self-esteem. Other psychosocial factors assessed included self-efficacy, motivation, and stage of readiness for weight-related behavior change.

Intervention participation

Intervention participation is measured 1 month postintervention in three ways: through program records of attendance at classes and completion of counseling calls; through questions about interaction with other AMP participants; and through questions about time spent engaging with intervention materials, including the informational notebook, pedometer, and sport stroller.

Intermediate outcomes

Dietary intake is measured at baseline and 1 month postintervention using the Minnesota Nutrition Data System (NDS),32 a telephone-administered, multiple-pass, 24-hour dietary recall technique (the primary measure of dietary change). Dietary recalls are collected on 2 randomly selected days over a 2-week period. Prior to the telephone interview, the participant was mailed two-dimensional food portion visuals to assist in determining portion sizes. At 6 and 12 months postintervention, brief assessments of the number of servings of soda and other sweetened beverages, fast food meals, French fries and snack chips, and fruits and vegetables are administered, so we can estimate how well diet has been maintained at points when the longer, more burdensome NDS will not be assessed. Because they assess intake in different ways from the NDS, these questions are also asked at baseline and 1 month postintervention for comparison to the later assessments.

The 7-day Physical Activity Recall (PAR)33 is used to estimate daily energy expenditure at baseline and at 1 month postintervention (the primary outcome measure of physical activity change). The PAR is interviewer administered to capture detail regarding the duration, intensity, and volume of physical activity. Questions separately capture the number and duration of bouts of moderate, hard, and very hard activity in the morning, afternoon, and evening of each of the 7 days of the previous week. At 6 and 12 months postintervention, brief physical activity questions from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)34 are also administered so we can estimate how well physical activity has been maintained at points when the longer, more burdensome PAR will not be assessed. Because they assess activity in different ways from the PAR (minutes per day in activity where “heart rate is increased and you breathe harder”), the questions are also asked at baseline and 1 month postintervention for comparison with the later assessments.

Primary outcome

BMI change from baseline to 12 months postintervention (24 months postpartum) is assessed in person by weighing all participants. Logistic regression will be used to determine if the two arms are significantly different in the proportion of women who lose at least 10% of BMI from baseline to 24 months postpartum, controlling for important baseline covariates, such as BMI and race. We assume that 20% of the 450 enrolled women will be lost to follow-up and not be used in the analyses, leaving 360 women with complete data. With this sample size, we have an 80% power to detect a true arm difference of 5% vs. 13.5%.

Three separate general linear models will be used to test whether the two arms are significantly different in change from baseline to 1 month postintervention in calorie intake, calorie intake from fat, or calorie expenditure, again controlling for important baseline covariates, including the baseline value of the outcome measure modeled.

Secondary analyses

We consider all parts of the intervention (including the classes, the written materials, the stroller, and the counseling sessions) as a whole, and our primary analyses will be intent-to-treat. However, in secondary multivariate analyses, we plan to evaluate the relationship between participation in and engagement with the various parts of the intervention (the physical activity classes, nutrition classes, and counseling calls), the intermediate behavioral outcomes, and the final BMI outcome. Additionally, because of the high African American representation in our community and consequently our sample, any outcomes can be analyzed separately by race.

Results

Randomization resulted in the assignment of 225 women to each arm of the trial, with stratification by race and parity. Black women are well represented, comprising 45.1% of our final sample. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of our study sample are presented by study arm and by race in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline Sociodemographic Variables by Study Arm and by Racea

| Variable | Total (n = 450) | Intervention (n = 225) | Control (n = 225) | White (n = 237) | Black (n = 203) | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 30.9 (5.6) | 30.6 (5.8) | 31.2 (5.3) | 32.2 (5.1) | 29.3 (5.7) | <0.0001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 53% (237) | 52% (118) | 53% (119) | 100% (237) | ||

| Black | 45% (203) | 45% (101) | 45% (102) | 100% (203) | ||

| Other races | 2.2% (10) | 2.7% (6) | 1.8% (4) | |||

| Hispanic | 2.4% (11) | 1.8% (4) | 3.1% (7) | 4.2% (10) | 0.5% (1) | |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 7.1% (32) | 7.1% (16) | 7.1% (16) | 2.5% (6) | 13% (26) | <0.0001 |

| High school graduate | 14% (61) | 13% (29) | 14% (32) | 8.9% (21) | 20% (40) | |

| Some college | 19% (85) | 20% (45) | 18% (40) | 14% (32) | 26% (52) | |

| Associate degree | 5.6% (25) | 4.0% (9) | 7.1% (16) | 5.5% (13) | 5.9% (12) | |

| College degree | 33% (150) | 32% (72) | 35% (78) | 40% (94) | 26% (52) | |

| Graduate degree | 22% (97) | 24% (54) | 19% (43) | 30% (71) | 10% (21) | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single/never married | 17% (76) | 19% (43) | 15% (33) | 3.4% (8) | 34% (68) | <0.0001 |

| Living with partner | 11% (49) | 8.4% (19) | 13% (30) | 3.0% (7) | 20% (41) | |

| Married | 69% (309) | 70% (157) | 68% (152) | 92% (217) | 41% (83) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 3.6% (16) | 2.7% (6) | 4.4% (10) | 2.1% (5) | 5.4% (11) | |

| Household income | ||||||

| Up to $15,000 | 6.2% (28) | 8.4% (19) | 4.0% (9) | 1.7% (4) | 12% (24) | <0.0001 |

| $15,001–$30,000 | 21% (94) | 21% (48) | 20% (46) | 9.3% (22) | 35% (71) | |

| $30,001–$45,000 | 14% (65) | 12% (28) | 16% (37) | 13% (30) | 17% (34) | |

| $45,001–$60,000 | 15% (66) | 13% (30) | 16% (36) | 17% (41) | 11% (22) | |

| $60,001 or more | 41% (185) | 40% (90) | 42% (95) | 56% (133) | 23% (47) | |

| Insurance type | ||||||

| Private/through employer | 73% (327) | 72% (163) | 73% (164) | 88% (209) | 54% (110) | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid | 24% (107) | 24% (54) | 24% (53) | 9.7% (23) | 40% (82) | |

| None | 3.5% (16) | 3.6% (8) | 3.6% (8) | 2.1% (5) | 5.4% (11) | |

| Planning to work at 6 months postpartum | ||||||

| Full-time | 63% (282) | 60% (136) | 65% (146) | 50% (118) | 77% (157) | <0.0001 |

| Part-time | 18% (81) | 20% (44) | 16% (37) | 23% (54) | 13% (26) | |

| Not work for pay | 18% (83) | 19% (43) | 18% (40) | 26% (61) | 9.9% (20) | |

| Current child care arrangement | ||||||

| Stays at home with mom | 73% (330) | 72% (163) | 74% (167) | 80% (189) | 65% (132) | <0.01 |

| Stays at home with relative | 8.7% (39) | 8.9% (20) | 8.4% (19) | 6.8% (16) | 11% (23) | |

| Day care | 4.9% (22) | 4.0% (9) | 5.8% (13) | 4.6% (11) | 5.4% (11) | |

| Combination of above | 12% (55) | 13% (30) | 11% (25) | 8.4% (20) | 17% (34) | |

Data presented are % (n), except where noted.

For difference by race. Chi-square test for differences in proportions; t test for differences in means.

Our study sample is highly educated, with significant differences by race. Racial differences are most pronounced in economic factors, including household income, insurance type, and plans to work for pay. More than half the white participants report household incomes >$60,000 per year, whereas less than a quarter of black participants do. Similarly, the majority of white participants (88%) have private insurance, whereas 40% of black participants are insured through Medicaid.

Health and pregnancy variables are presented in Table 3, also by study arm and by race. The mean BMI of women entering the study is 33.0, although black women tend to be heavier than white women. White women are concentrated in the lighter BMI ranges, with almost half in the 25–29.9 kg/m2 category. White women are more likely to be primiparous and have a lower mean number of children. White women are also more likely to be breastfeeding than black women at 6 weeks postpartum.

Table 3.

Baseline Health and Pregnancy Variables, by Study Arm and by Racea

| Variable | Total (n = 450) | Intervention (n = 225) | Control (n = 225) | White (n = 237) | Black (n = 203) | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | ||||||

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 33.0 (6.4) | 33.1 (6.7) | 32.9 (6.0) | 31.5 (5.3) | 34.8 (7.2) | <0.0001 |

| 25–29.9 | 40% (180) | 39% (88) | 41% (92) | 49% (116) | 27% (55) | <0.0001 |

| 30–34.9 | 31% (141) | 34% (77) | 28% (64) | 31% (74) | 33% (66) | |

| 35–39.9 | 16% (70) | 13% (29) | 18% (41) | 12% (28) | 21% (42) | |

| 40+ | 13% (59) | 14% (31) | 12% (28) | 8.0% (19) | 20% (40) | |

| Weight loss since delivery, mean (SD), kg | 10.4 (5.1) | 10.8 (5.2) | 9.9 (4.9) | 10.7 (5.0) | 10.0 (5.2) | 0.18 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy, mean (SD), kg | 15.0 (8.7) | 15.3 (8.7) | 14.6 (8.8) | 15.6 (7.6) | 14.2 (9.9) | 0.11 |

| Pregnancy | ||||||

| Primiparous | 41% (185) | 41% (93) | 41% (92) | 45% (107) | 35% (71) | 0.03 |

| Live births, mean (SD), including newborn | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.8 (0.9) | 2.1 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Infant feeding | ||||||

| Breastfeeding only | 36% (160) | 38% (85) | 33% (75) | 48% (114) | 21% (43) | <0.0001 |

| Combined breastfeeding and formula | 28% (128) | 26% (58) | 31% (70) | 25% (59) | 32% (64) | |

| Formula feeding only | 36% (162) | 36% (82) | 36% (80) | 27% (64) | 47% (96) | |

| Health | ||||||

| Self-reported health status | ||||||

| Excellent | 20% (88) | 18% (41) | 21% (47) | 22% (53) | 16% (33) | <0.01 |

| Very good | 40% (180) | 40% (90) | 40% (90) | 45% (106) | 34% (68) | |

| Good | 31% (140) | 32% (72) | 30% (68) | 27% (63) | 37% (75) | |

| Fair | 8.9% (40) | 9.3% (21) | 8.4% (19) | 6.3% (15) | 12% (25) | |

| Poor | 0.4% (2) | 0.4% (1) | 0.4% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 1.0% (2) | |

| Self-reported medical conditions | 20% (92) | 20% (45) | 21% (47) | 18% (43) | 23% (46) | 0.24 |

| Currently smoking | 5.8% (26) | 4.4% (10) | 7.1% (16) | 4.2% (10) | 7.9% (16) | 0.10 |

| Postpartum incontinence | 16% (72) | 16% (36) | 16% (36) | 21% (49) | 9.9% (20) | <0.01 |

| Postpartum depression, mean (SD), scale 0–30 | 6.6 (4.5) | 6.8 (4.7) | 6.3 (4.3) | 6.2 (4.3) | 6.9 (4.8) | 0.11 |

| Percent depressed (EPDS ≥13) | 8.7% (39) | 10% (23) | 7.1% (16) | 7.6% (18) | 9.9% (20) | 0.40 |

| Nutritional Data System (NDS) | ||||||

| Caloric intake, mean (SD), kcal/day | 1877 (661) | 1887 (680) | 1867 (643) | 1964 (633) | 1777 (691) | <0.01 |

| Average % calories from fat, mean (SD) | 34% (7.6) | 34% (7.8) | 34% (7.3) | 34% (7.7) | 35% (7.4) | 0.06 |

| Brief food frequency questions | ||||||

| Soda, mean (SD), servings/day | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.9) | 1.0 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Sweetened beverages, mean (SD), per day | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.6 (0.9) | 1.4 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Fast food, mean (SD), servings/week | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Fries or chips, mean (SD), servings/day | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.8) | 1.0 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Fruits/vegetables, mean (SD), servings/day | 3.4 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.4 (1.4) | 3.4 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.5) | 0.37 |

| 7-day Physical Activity Recall (PAR) | ||||||

| Moderate activity, mean (SD), min/day | 33.3 (55.7) | 34.2 (55.6) | 32.5 (55.9) | 31.3 (48.8) | 36.5 (63.8) | 0.34 |

| Hard/very hard activity, mean (SD), min/day | 6.7 (14.6) | 8.2 (17.7) | 5.2 (10.5) | 6.6 (12.7) | 6.9 (16.8) | 0.88 |

| Brief physical activity questions (BRFSS) | ||||||

| Total activity, mean (SD), min/day | 21.1 (36.8) | 19.7 (25.8) | 22.4 (45.1) | 18.7 (23.0) | 24.0 (48.6) | 0.14 |

Data presented are % (n), except where noted.

For difference by race. Chi-square test for differences in proportions; t test for differences in means.

Only 19.6% of participants feel their health is excellent, with notable racial differences, and self-reported medical conditions are high. Current smoking is relatively low. Incontinence is reported by twice as many whites as blacks, and (using a cutoff of 12/13 on the EPDS, range 0–30), postpartum depression is slightly more common in black respondents.

Reported average dietary intake is close to 1900 calories per day, lower in blacks, with 34% of calories from fat. Moderate activity, such as shopping or housework, is limited to about half an hour per day, with vigorous activity extremely limited in both groups. There are no significant racial differences in reported physical activity.

Discussion

AMP is designed to be disseminated broadly to benefit the public health. A high proportion of black participants, representative of our local community, will give us the ability to stratify the outcome analyses to assess the presence of racial differences.

Our study participants are better educated than the U.S. population.35 This is also a characteristic of the local community, which includes the Research Triangle Park and numerous research universities. Racial differences in level of education are statistically significant, however, reflecting similar national disparities.35 Significant racial differences in proportions of single and married mothers and the younger age of black mothers also reflect national data.35,36 The range of socioeconomic backgrounds increases the representativeness of our sample, and we consider the inclusion of participants from less affluent households to be a strength of our study. In general, the sample reflects the greater U.S. population, and outcomes of the study should be generalizable.

The rate of any breastfeeding (either solely or combined with formula) and the racial differences in our sample are similar to national rates, although exclusive breastfeeding is lower than the national average for both white and black participants.37

Perhaps as a result of their postpartum status, self-reported health is relatively poor in this sample of women of childbearing age. The proportions with self-reported medical conditions are also high considering the ages of the respondents. Illnesses reported include asthma, hypertension, and diabetes (data not shown), known weight-related comorbidities that could improve through participation in an intervention such as ours. The overall rate of postpartum depression is similar to the national average.38 Total caloric intake is somewhat lower than in two earlier reports (2200–2400)39,40; this may be because both earlier reports were of exclusively lactating women. The average calories from fat, however, is 10% higher in our sample.39

Study design alternatives

We considered a number of alternative approaches to the study design. For example, we considered including women who were of normal weight before pregnancy but who gained more weight in pregnancy than recommended. We decided against including these, however, because the literature suggests normal weight women (even the high gainers) return to prepregnancy weight without formal intervention.7,41

Another alternative would have been to compare our participants' weight trajectories and eating and activity behaviors with those of nonpregnant controls. A more complex four-arm design including nonpregnant women (who did and did not receive the AMP intervention) would have been optimal to evaluate our TM hypotheses. As the postpartum period requires specific intervention considerations (e.g., the presence of an infant, dietary impact on breastfeeding), however, an intervention for nonpostpartum women would by design have been very different, making direct comparisons more complicated. The substantial increase in complexity and sample size, therefore, convinced us against this alternative.

The length of follow-up was also an important design consideration. Short-term weight loss is usually much easier to achieve than longer-term weight loss.16 Our primary end point (BMI change at 12 months postintervention, i.e., 24 months postpartum) strikes a balance between following the women long enough to assess long-term outcomes and what is feasible within a 5-year study.

Limitations

Although the primary outcome is the difference between two actual weights (24 months postpartum vs. baseline), prepregnancy weight and gestational weight gain, which are covariates in some of the analyses, are based on self-report. Women who had twins or preterm births were not excluded from the study, but singleton/twin status and the birth weight of the baby were collected. Although such variables may have an effect on gestational weight gain, itself an important predictor of postpartum weight change, these factors can be controlled for in multivariable analyses. There were no major differences in baseline characteristics by study arm. Although there were slight variations by arm in the baseline measures of physical activity, the outcome analyses will be adjusted for any imbalances in the baseline values of the outcome measures as well as other important baseline covariates.

Conclusions

Behavior change interventions based on principles of social cognitive theory,20 stage of readiness,21 and other models42–44 that coincide with a TM have the potential to promote postpartum weight loss. The key assumptions are that (1) motivational cues to action are critical catalysts of behavior change, (2) behavior change is facilitated by feelings of confidence, which are enhanced when individuals have the necessary skills to make lifestyle changes, and (3) ongoing support maintains confidence and skills needed to sustain behavior change. We posit that predisposing factors and the TM directly influence the social-cognitive mediators that in turn lead to dietary and activity modifications that enhance the potential for weight loss. Our assessment of critical variables within each of these domains will enable us to examine the potency of the postpartum transition as a cue to action and suggest treatment matching opportunities for future interventions. Investigation of differences in predictors, outcomes, and mediators by race, especially differences in the TM dimensions, may point toward an emphasis on differences in optimal intervention strategies for black and white postpartum women.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the following faculty and staff who contributed to the development and execution of this project: Anne Jacobs-Kenyon, Hannah Harvey, Jessica Revels, Holiday Durham, Lori Carter-Edwards, Miranda West, Debra Freeman, Cheyenne Beach, Marie Harvin, Heather Ayella, and Ashley Mathis.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. This study is funded through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), RO1 DK064986.

References

- 1.Williamson DF. Kahn HS. Remington PL. Anda RF. The 10-year incidence of overweight and major weight gain in U.S. adults. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rooney BL. Schauberger CW. Excess pregnancy weight gain and long-term obesity: One decade later. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gore SA. Brown DM. West DS. The role of postpartum weight retention in obesity among women: A review of the evidence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:149–159. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2602_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunderson EP. Abrams B. Epidemiology of gestational weight gain and body weight changes after pregnancy. Epidemiol Rev. 1999;21:261–275. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohlin A. Rossner S. Maternal body weight development after pregnancy. Int J Obes. 1990;14:159–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossner S. Ohlin A. Pregnancy as a risk factor for obesity: Lessons from the Stockholm Pregnancy and Weight Development Study. Obes Res. 1995;3(Suppl 2):267s–275s. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunderson EP. Abrams B. Selvin S. Does the pattern of postpartum weight change differ according to pregravid body size? Int J Obes. 2001;25:853–862. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowell DT. Weight change in the postpartum period: A review of the literature. J Nurse Midwifery. 1995;40:418–423. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(95)00049-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker JD. Abrams B. Differences in postpartum weight retention between black and white mothers. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:768–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keppel KG. Taffel SM. Pregnancy-related weight gain and retention: Implications of the 1990 Institute of Medicine guidelines. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1100–1103. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.8.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DE. Lewis CE. Caveny JL. Perkins LL. Burke GL. Bild DE. Longitudinal changes in adiposity associated with pregnancy—The CARDIA study. JAMA. 1994;271:1747–1751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boardley DJ. Sargent RG. Coker AL. Hussey JR. Sharpe PA. The relationship between diet, activity, and other factors, and postpartum weight change by race. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:834–838. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00283-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohlin A. Rossner S. Factors related to body weight changes during and after pregnancy: The Stockholm Pregnancy and Weight Development Study. Obes Res. 1996;4:271–276. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1996.tb00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohlin A. Rossner S. Trends in eating patterns, physical activity and socio-demographic factors in relation to postpartum body weight development. Br J Nutr. 1994;71:457–470. doi: 10.1079/bjn19940155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson CM. Strawderman MS. Hinton PS. Pearson TA. Gestational weight gain and postpartum behaviors associated with weight change from early pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Int J Obes Rel Metab Disord. 2003;27:117–127. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeffery RW. Drewnowski A. Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: Current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19(Suppl 1):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. NIH publication no.98–4083. National Institutes of Health. [Sep;1998 ]. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.htm www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.htm

- 18.Amorim AR. Linne YM. Lourenco PM. Diet or exercise, or both, for weight reduction in women after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD005627. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005627.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBride CM. Emmons KM. Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: The case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003;18:156–170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prochaska JO. DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller WR. Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Østbye T. McBride C. Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Interest in healthy diet and physical activity interventions peripartum among female partners of active duty military. Mil Med. 2003;168:320–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wing RR. Jeffery RW. Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:132–138. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beilock SL. Feltz DL. Pivarnik JM. Training patterns of athletes during pregnancy and postpartum. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2001;72:39–46. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2001.10608930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinton PS. Olson CM. Postpartum exercise and food intake: The importance of behavior-specific self-efficacy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:1430–1437. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resnicow K. DiIorio C. Soet JE. Ernst D. Borrelli B. Hecht J. Motivational interviewing in health promotion: It sounds like something is changing. Health Psychol. 2002;21:444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resnicow K. DiIorio C. Soet J, et al. Motivational Interviewing in medical and public health settings. In: Miller W, editor; Rollnick S, editor. Motivational Interviewing. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uebersax JS. Wyman JF. Shumaker SA. McClish DK. Fantl JA. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Neurourol Urodyn. 1995;14:131–139. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox JL. Holden JM. Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson D. Clark LA. Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota. Nutrition data system for research. www.ncc.umn.edu/ www.ncc.umn.edu/

- 33.Sallis JF. Haskell W. Wood PD. Rogers T. Blair SN. Paffenbarger RS. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. www.cdc.gov/brfss/ www.cdc.gov/brfss/

- 35.U.S. Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2007 (Tables 215, 216, 83) www.census.gov/compendia/statab/ www.census.gov/compendia/statab/

- 36.Mathews TJ. Hamilton BE. National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 51, No. 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Mean age of mother, 1970–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li R. Darling N. Maurice E. Barker L. Grummer-Strawn LM. Breastfeeding rates in the United States by characteristics of the child, mother, or family: The 2002 National Immunization Survey. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e31–37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaynes BN. Gavin N. Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 119. AHRQ Publication 05-E006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lovelady CA. Stephenson KG. Kuppler KM. Williams JP. The effects of dieting on food and nutrient intake of lactating women. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:908–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mackey AD. Picciano MF. Mitchell DC. Smiciklas-Wright H. Self-selected diets of lactating women often fail to meet dietary recommendations. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:297–302. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thorsdottir I. Birgisdottir BE. Different weight gain in women of normal weight before pregnancy: Postpartum weight and birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:806–820. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinstein ND. Why it won't happen to me: Perceptions of risk factors and susceptibility. Health Psychol. 1984;3:431–457. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.3.5.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ajzen I. Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]