Abstract

Objective: This study evaluated time to response in the treatment of panic disorder with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) combined with alprazolam orally disintegrating tablets (ODT), or SSRI/SNRI alone.

Design: Subjects were randomized to eight weeks open-label treatment with alprazolam ODT (4 weeks treatment followed by 3–4 week taper) combined with an SSRI or SNRI, or treatment with SSRI/SNRI alone.

Setting: The study was conducted under naturalistic conditions at 62 primary care and 34 psychiatric practices.

Participants: Male or female subjects ≥18 years of age diagnosed with panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia.

Measurements: The primary efficacy measure was time to response, defined as ≥50-percent decrease from baseline Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) total score. Secondary measures included change from baseline in HAM-A scores and the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I) and Patient Global Impression (PGI) scales.

Results: The intent-to-treat (ITT) population comprised 245 subjects. There was no statistical difference between treatment groups in time to response in the ITT population; however, a prospectively defined per protocol analysis revealed a statistically significant earlier onset of effect in subjects receiving SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT (P<0.05). Mean change from baseline in HAM-A total score and clinician and patient measures of global improvement also showed statistically significant early advantages for combination therapy compared with SSRI/SNRI monotherapy.

Conclusion: Combined treatment of panic disorder with alprazolam ODT and an SSRI/SNRI may be associated with more rapid improvement in anxiety symptoms compared with an SSRI/SNRI alone.

Keywords: panic disorder, SSRI, SNRI, alprazolam, naturalistic

INTRODUCTION

Panic disorder is a chronic and disabling condition characterized by recurrent, acute attacks of extreme fear or foreboding, followed by persistent worry about future attacks and/or a significant change in behavior resulting from an attack.1,2 Epidemiologic studies suggest lifetime prevalence rates of 2 to 5 percent;3–5 however, the incidence of panic disorder among patients who present to primary care may be substantially higher.6,7

Although several classes of medications have proven useful in the treatment of panic disorder,8 in recent years selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as well as serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have emerged as first-line agents, having an improved side effect profile compared with tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and a reduced potential for physical dependence and withdrawal phenomena relative to benzodiazepines.9,10 Results from controlled clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of SSRIs11–14 and the SNRI venlafaxine15 in panic disorder, and a number of these medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication.

SSRIs and SNRIs have disadvantages, however, such as a relatively slow onset of action and the potential to exacerbate symptoms of anxiety early during treatment.9,16 Since benzodiazepines act comparatively rapidly to relieve symptoms of anxiety, it is not uncommon for clinicians to co-prescribe benzodiazepines with SSRIs or SNRIs in the treatment of anxiety disorders,17 despite rather limited published evidence for the efficacy and safety of this therapeutic strategy. Results from two small, placebo-controlled studies have suggested that initiating treatment with a benzodiazepine combined with an SSRI is generally safe and may be associated with an accelerated anxiolytic response,18,19 but it is not clear whether these findings are generalizable to the broader population of patients treated in psychiatric and primary care practices.

The current study was conducted in a relatively large sample of subjects with a primary diagnosis of panic disorder, treated in a naturalistic setting. Its purpose was to evaluate time to response in symptoms of anxiety and overall safety of alprazolam orally disintegrating tablets (Niravam™) combined with an SSRI or SNRI, compared to treatment with SSRI/SNRI alone.

METHODS

This Phase IV multicenter, randomized, open-label, naturalistic study was conducted at 62 primary care and 34 psychiatric practices in the US from November 7, 2005, through June 7, 2006.

Subjects. Male or female ambulatory subjects ≥18 years of age with a primary diagnosis of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, were potentially eligible for inclusion in this study if, in the investigator's judgment, an SSRI or SNRI would be prescribed as standard practice. Diagnosis was confirmed prior to randomization by the Mental Health Screener® (MHS), a validated scale20 administered via a computer-assisted Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS). Subjects with positive results for both panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) on the MHS were, for the purposes of this study, considered to have a primary diagnosis of panic disorder. The MHS was used to ensure that diagnoses of panic disorder and psychiatric comorbidity were performed consistently in both primary care and psychiatric sites.

Subjects were excluded from the study if they had received treatment with an SSRI or SNRI within one week (6 weeks for fluoxetine) of study entry, or if they had received treatment within the last two, four, or 10 days with, respectively, a short-acting, intermediate-acting, or long-acting benzodiazepine.

Subjects also were excluded if they met criteria for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, alcohol abuse/dependence, or any other psychiatric or medical condition that, in the opinion of the investigator, would compromise study participation. Subjects who were considered at current risk for suicide were ineligible for participation, as were those with contraindication(s) or history of hypersensitivity to any SSRI, SNRI, or benzodiazepine. Use of any prescription hypnotic, or any antidepressant, anxiolytic, or benzodiazepine other than the study medication(s) was prohibited. Individuals who had initiated cognitive therapy within 60 days of the current study were not eligible to participate and initiation of cognitive therapy during the study was prohibited. Individuals who had participated in another clinical trial within 30 days or women who were pregnant, nursing, or of child-bearing potential and not using a medically accepted method of contraception also were excluded from participation.

The study protocol was approved by a central institutional review board on behalf of all participating centers, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Study Design. Eligible subjects were to be prescribed an SSRI/SNRI (considered standard care by the investigator), and then randomized via IVRS in a 1:1 ratio to eight weeks of treatment with or without alprazolam orally disintegrating tablets (ODT), administered in accordance with US prescribing information. After four weeks of treatment, the alprazolam ODT dose was to be tapered over the next 3 to 4 weeks, with the taper completed at the end of the eight-week study period.

Subjects were personally responsible for obtaining the prescribed SSRI/SNRI and adhering to the prescribed dosing regimen. Subjects randomized to receive alprazolam ODT were provided with a unit dose pack (to ensure that dosing began on the day of randomization), together with a prescription and prescription card to be used at the pharmacy of their choice. Subjects' adherence to therapy was measured by self report.

Assessments. A determination of study eligibility, including demographic characteristics and medical history, was made at the initial visit. Investigator assessments of subjects at Weeks 2, 4, and 8 (or upon early termination) of the study were conducted using the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I),21 which rates overall change from baseline on a seven-point scale from “very much better” to “very much worse.” The Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A)22 was administered at baseline and weekly for eight weeks using the validated IVRS.23,24 The HAM-A includes 14 items (divided between psychic and somatic domains), with severity of each item rated on a scale of 0 to 4 (maximum total score of 56). The IVRS system was used to provide consistency in evaluation across the large number of participating sites and lessen the impact of investigator bias potentially associated with an open-label study. Additionally, since many of the participating sites do not routinely conduct psychiatric clinical trials, use of the clinician-rated HAM-A (or other instrument specific to panic disorder) was deemed impractical. Also via the IVRS, subjects were queried at baseline and weekly about the presence or absence of panic attacks during the previous week, and weekly regarding their overall assessment of improvement using the seven-point Patient Global Impression (PGI) scale.

The primary efficacy variable was time to response in the symptoms of anxiety, with response defined as a decrease from baseline of ≥50 percent in HAM-A total score. Other efficacy variables included mean change from baseline in HAM-A total score, mean change from baseline in HAM-A insomnia, psychic, and somatic subscores, and proportion of HAM-A responders. Measures of overall improvement included the investigator-rated CGI-I scale, the subject-rated PGI, and the absence of panic attacks.

Safety assessments were conducted at each visit and the incidence and severity of any adverse events, including those spontaneously reported during phone contact with subjects, were recorded on the subject's case report form. Daily dosage of the SSRI/SNRI was collected at initiation of the treatment and at the last visit. Daily dosage of alprazolam ODT was collected at initiation of treatment, just prior to the beginning of the taper and at the last visit, if the subject had not completed the taper.

Statistical analysis. The primary efficacy variable in this study was time to response in the symptoms of anxiety, with response defined prospectively as a decrease of ≥50 percent from baseline in IVRS HAM-A total score. Time to response was defined as the first time point at which the response criterion was observed, and the distribution for each treatment group was calculated using Kaplan-Meier estimates.25 The treatment groups were compared using the Generalized Wilcoxon nonparametric survival statistic.26 The sample size was calculated to detect with 80-percent power a 13-percent difference between treatment groups in early time to response.

The secondary variables, including mean change from baseline in HAM-A total score and subscores, were analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)27 model, on change from baseline with treatment as a fixed effect and the corresponding baseline total or subscale HAM-A score as a covariate. Distribution of CGI-I and PGI scores were analyzed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests28 to compare scores between treatment groups. Pearson Chi-Square tests29 were used to compare the difference between the treatment groups in proportion of responders and presence of any panic attacks in the past week.

Unless otherwise specified, all statistical tests were two-sided, with a significance level of α=0.05. The safety population comprised all subjects who received at least one dose of the medication(s) they were assigned to receive (an SSRI/SNRI with or without alprazolam ODT). Efficacy analyses were based on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population of subjects who received at least one dose of prescribed medication(s) and had at least one assessment post-baseline; unless otherwise specified, efficacy data are presented by week for observed cases. A prospectively defined “per protocol” analysis of subjects with no major protocol violations was performed only for the primary endpoint of time to response.

RESULTS

Study population. A total of 275 subjects met study eligibility criteria and were randomized via IVRS to treatment with alprazolam ODT in combination with an SSRI/SNRI or treatment with an SSRI/SNRI alone. Three subjects randomized to SSRI/SNRI monotherapy did not receive study medication; thus the safety population comprised 137 subjects randomized to treatment with SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT, and 135 subjects randomized to treatment with SSRI/SNRI alone. Efficacy analyses were performed on the ITT subset of subjects that received study medication and had at least one post-baseline assessment, which included 125 subjects treated with SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT and 120 subjects treated with SSRI/SNRI alone. The per protocol population, which excluded subjects with major protocol violations (such as those not meeting eligibility criteria, those not prescribed an SSRI or SNRI, and those taking a prohibited medication concomitantly) consisted of 104 subjects treated with SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT and 106 subjects treated with SSRI/SNRI alone.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects in the ITT population were generally similar between treatment groups and are summarized in Table 1. Most subjects were moderately to severely ill at baseline, with mean HAM-A total scores of 28.5 in the SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT group and 26.9 in the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group. Psychiatric history and current clinical status were similar between groups, with the exception that at baseline a significantly higher proportion of subjects randomized to the SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT treatment group were positive for both panic disorder and GAD on the MHS compared to the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group (79% vs. 65%, χ2(1)=6.16, P<0.05), and a greater proportion of subjects in the combination treatment group had positive diagnoses for comorbid mood disorder—predominantly major depressive disorder—compared to the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group (86% vs. 76%, χ2 (1)=4.48, P<0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the ITT population at baseline

| SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT N=125 | SSRI/SNRI alone N=120 | |

|---|---|---|

Age (years)

|

|

|

| Gender (% female) |

|

|

Ethnic origin (%)

|

|

|

Diagnosis of panic disorder (%)

|

|

|

Duration of panic disorder (years)

|

|

|

Comorbid disorders (%)

|

|

|

HAM-A (mean score ± SD)

|

|

|

| Panic attack(s) in previous week (%) |

|

|

P<0.05 SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT versus SSRI/SNRI alone

Two-thirds of all randomized subjects (67% in each of the treatment groups) completed the study. Reasons for premature discontinuation are presented in Table 2. Loss to follow-up and withdrawal of consent were the most common reasons, while relatively few subjects in either treatment group withdrew for lack of efficacy or adverse events. There were no important differences between treatment groups in proportions of subjects or reasons for early drop-out.

Table 2.

Subject disposition

| SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT N (%) | SSRI/SNRI alone N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized |

|

|

| Completed study |

|

|

Discontinued study

|

|

|

Medication doses. The SSRIs and SNRIs that were prescribed to subjects in the ITT population included citalopram (n=4), escitalopram (n=96), fluoxetine (n=11), paroxetine (n=16), paroxetine controlled release (n=13), sertraline (n=60), duloxetine (n=7), venlafaxine (n=15), and venlafaxine extended release (n=14). Mean endpoint doses for the SSRIs/SNRIs (Table 3) were generally consistent with labeling information for panic disorder (or for GAD or major depression, for those SSRIs/SNRIs without an FDA-approved indication for panic disorder).

Table 3.

Mean ending doses of SSRIs and SNRIs in the ITT population

| SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT N=125 | SSRI/SNRI alone N=120 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean Dose (mg/day) | n | Mean Dose (mg/day) | |

SSRIs

|

|

|

|

|

SNRIs

|

|

|

|

|

| Othera | 6 | -- | 3 | -- |

| Not Availableb | 14 | -- | 9 | -- |

Subjects not receiving an SSRI/SNRI

Subjects for whom an endpoint dose was not recorded, including subjects receiving duloxetine plus alprazolam ODT (n=1), escitalopram plus alprazolam ODT (n=7), paroxetine plus alprazolam ODT (n=1), paroxetine CR plus alprazolam ODT (n=1), sertraline plus alprazolam ODT (n=2), venlafaxine plus alprazolam ODT (n=1), venlafaxine XR plus alprazolam ODT (n=1), escitalopram alone (n=6), fluoxetine alone (n=1), and sertraline alone (n=2)

Mean, median, and distribution of alprazolam ODT doses used in the ITT population (N=125) are summarized in Table 4. There were no statistically significant differences between psychiatric and primary care sites with respect to dosing. The mean starting dose was 1.09mg/day, given in divided doses; more than 90 percent of subjects received starting doses of alprazolam ODT of 1.50mg/day. At Week 4, the mean dose of alprazolam ODT was 1.01mg/day, given in divided doses. At study completion (or early termination), 71 subjects (57%) in the ITT population had been completely tapered off alprazolam ODT; the mean dose of alprazolam ODT at endpoint for those subjects not fully tapered was 1.00mg/day. Analysis of the subset of the 112 subjects still in the study at the start of the taper showed that 68 (61%) successfully completed the taper by Week 8. Analysis of subjects who completed the study showed that 62 of 92 (67%) study completers were tapered off alprazolam ODT by Week 8. There was no correlation between alprazolam ODT dose at Week 4 and successful completion of taper by Week 8.

Table 4.

Distribution of alprazolam ODT doses at Baseline, Week 4, and Endpoint

| Starting Dose ITT N=125 | Week 4 Dose ITT N=125 | Endpoint Dose ITT N=125 | Endpoint Dose Completers N=92 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (mg/day)a |

|

|

|

|

| Median (mg/day)a |

|

|

|

|

Range, n (%)

|

|

|

|

|

Means and medians calculated for subjects receiving any dose >0

Subjects for whom a dose was not recorded

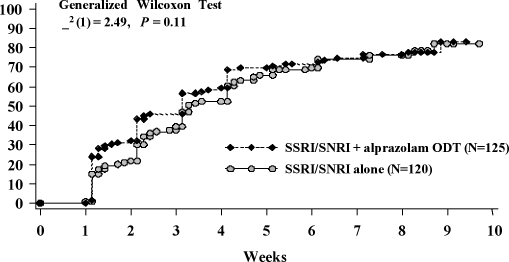

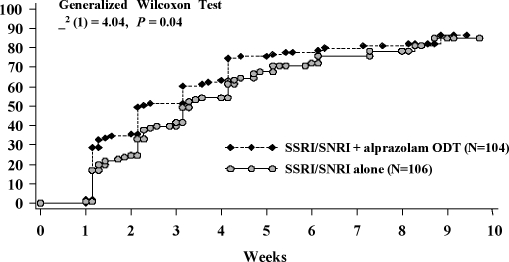

Efficacy. There was no statistically significant difference between treatment groups in time to response in anxiety symptoms in the ITT population using the Generalized Wilcoxon survival test and Kaplan-Meier estimate of response (Figure 1). A prospectively defined analysis of the per protocol population, however, showed that combination treatment with alprazolam ODT and an SSRI/SNRI was significantly associated (χ2 (1)=4.04, P<0.05) with an accelerated time to response compared with SSRI/SNRI monotherapy (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of time to response in the ITT population

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of time to response in per protocol population

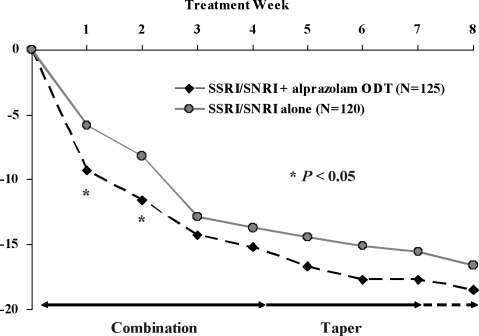

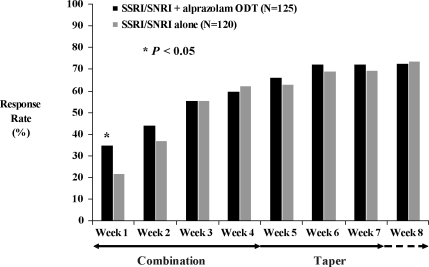

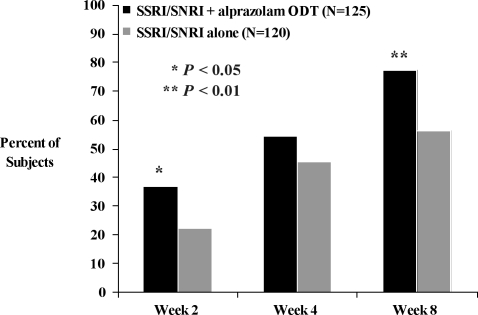

Analyses of secondary efficacy variables in the ITT population provided further evidence that combination treatment with alprazolam ODT and an SSRI/SNRI resulted in earlier improvement in anxiety symptoms compared with SSRI/SNRI alone. Statistically significant differences in mean change from baseline in HAM-A total scores (Figure 3) were apparent at Weeks 1 (-9.3 vs. -5.8, F(1,218)=5.76, P<0.05) and 2 (-11.6 vs. -8.2, F(1,208)=4.45, P<0.05), and a significantly higher proportion of subjects met response criteria at Week 1 (Figure 4) among those treated with an SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT compared with SSRI/SNRI alone (35% vs. 22%, χ2(1)=4.44, P<0.05). Statistically significant improvement in the HAM-A psychic factor subscore (which includes the items for anxiety, tension, fears, insomnia, cognitive difficulties, and depressed mood) also was observed at week 1 in subjects treated with the combination of SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT compared with SSRI/SNRI alone (-4.9 vs. -2.9, F(1,218)=7.29, P<0.01). There was no statistically significant difference between treatment groups in mean change from baseline in the HAM-A somatic factor subscore (which includes items for muscular, sensory, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genito-urinary, and autonomic symptoms), although there was a strong trend (-5.6 vs. -3.7, F(1,208)=3.86, P=0.051) in favor of the combination group at Week 2.

Figure 3.

Mean change from baseline in HAM-A total score

Figure 4.

Proportion of subjects with Ž 50% improvement from baseline in HAM-A total score

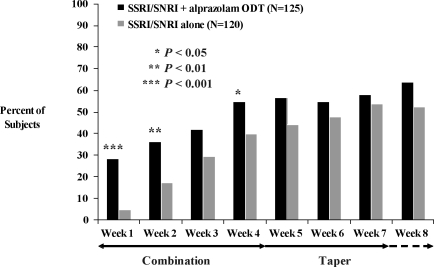

Both investigator- and subject-rated measures of global improvement favored combination treatment with alprazolam ODT and SSRI/SNRI versus SSRI/SNRI monotherapy (Figure 5). A significantly greater proportion of subjects treated with combination therapy versus monotherapy were considered much improved or very much improved on the CGI-I at Week 2 (37.0% vs. 22.4%, χ2 (1)=5.67, P<0.05) and at Week 8 (77.4% vs. 56.3%, χ2 (1)=9.53, P<0.01). Similarly, a greater proportion of subjects treated with SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT reported improvement on the PGI over the first weeks of treatment compared with those treated with SSRI/SNRI alone. At Week 1, 28.4 percent of subjects treated with the combination of SSRI/SNRI and alprazolam ODT reported feeling much better or very much better, compared with just 4.9 percent of subjects treated with SSRI/SNRI monotherapy (χ2 (1)= 20.63, P<0.001). A significant difference between groups on the PGI in the proportion of subjects who said they were feeling much better or very much better remained at Week 2 (36.4% vs. 17.3%, χ2(1)=9.83, P<0.01) and Week 4 (54.9% vs. 39.8%, χ2(1)=4.46, P<0.05).

Figures 5A and B.

Proportion of subjects rated “Very Much Improved” or “Much Improved” on A) the physician-rated CGI-I and B) the subject-rated PGI

The proportion of subjects with panic attacks in the previous week decreased markedly from baseline to Week 8. Among subjects receiving SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT, 92 percent experienced panic attacks in the week prior to study entry, compared with 30 percent in the week prior to the Week 8 visit. Among subjects treated with an SSRI/SNRI alone, 87 percent reported panic attacks in the week prior to baseline compared with 37 percent in the week prior to the Week 8 visit. There was no statistically significant difference between treatment groups at any time point in the proportion of subjects who experienced panic attacks.

Despite the protocol-directed taper of alprazolam ODT over the last four weeks of the study, there was no evidence on any measure of an increase in anxiety symptoms among subjects in the combination treatment group during the taper.

Safety and tolerability. Treatment with an SSRI/SNRI with or without alprazolam ODT was generally well tolerated in this study. Discontinuation due to treatment emergent adverse events occurred in just 5.1 percent of subjects receiving alprazolam ODT in combination with an SSRI/SNRI, and in 1.4 percent of subjects receiving an SSRI/SNRI alone. Overall, 37 percent of subjects receiving alprazolam ODT in combination with an SSRI/SNRI reported experiencing at least one adverse event, compared with 25 percent of subjects receiving an SSRI/SNRI alone (χ2(1)=4.59, P<0.05). Somnolence and headache were the only adverse events reported by greater than five percent of subjects in either treatment group, occurring, respectively, in 6.6 percent and 5.8 percent of subjects receiving alprazolam ODT in combination with an SSRI/SNRI, compared with 1.5 percent and 3.7 percent of subjects receiving SSRI/SNRI alone. Most adverse events occurred early in the study; over the last four weeks (during the alprazolam ODT taper) no single adverse event was reported by more than one subject in either treatment group, except headache, which was reported by two subjects in the combination group. The great majority (92%) of adverse events were classified as mild to moderate in nature. Serious adverse events, all of which required hospitalization or increased length of stay in hospital, occurred in three subjects receiving alprazolam ODT in combination with an SSRI/SNRI (intentional overdose of multiple medications; kidney infection, lobar nephronia; recurrent lower sternal postoperative infection, renal failure) and in two subjects receiving SSRI/SNRI alone (temporal arteritis; exacerbation of chronic bronchitis). None of these events was deemed by the investigator to be related to alprazolam ODT, and all subjects recovered.

DISCUSSION

Results from this large, naturalistic study suggest that in patients with panic disorder, initiating treatment with alprazolam ODT in combination with an SSRI/SNRI may produce a more rapid improvement in anxiety symptoms than treatment with an SSRI/SNRI alone. Compared with subjects treated with SSRI/SNRI monotherapy, those who received an SSRI/SNRI in combination with alprazolam ODT showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences in early improvement of anxiety symptoms as measured by a number of variables, including mean change from baseline in HAM-A total score, mean change from baseline in HAM-A psychic factors subscore (i.e., anxiety, tension, fears, insomnia, cognitive difficulties, and depressed mood items), proportion of HAM-A responders at Week 1, and investigator- and subject-rated measures of global improvement.

That there was no significant difference between treatment groups in the primary efficacy variable of time to response in the ITT population may reflect the imbalance at baseline in the proportion of subjects in the combination treatment group who met MHS diagnostic criteria for comorbid GAD and/or mood disorders compared with the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group, since psychiatric comorbidity is generally associated with poorer clinical response.30 It is also possible that differences between groups that occurred during the first week of treatment but prior to the first assessment were not detected. Alternatively, the failure to detect a difference in time to response in the ITT population may be a result of the naturalistic design of the study, which relied upon investigators to prescribe an appropriate SSRI/SNRI and subjects to adhere to the prescribed regimen. A prospectively defined per protocol analysis that excluded subjects with major protocol violations (e.g., subjects who were prescribed non-SSRI/SNRI antidepressants or other psychotropics) did, in fact, provide evidence of a statistically significant beneficial effect on early response in the SSRI/SNRI plus alprazolam ODT treatment group.

An advantage of this study's naturalistic design, and particularly its use of validated scales with the IVRS to confirm diagnoses and assess symptom severity, is that it permitted the participation of investigators in both primary care and specialty settings who are less experienced in clinical research but whose patient pool and approach to treatment may be more broadly representative of clinical practice.

The dosing strategy employed in this trial of four-weeks treatment with alprazolam ODT followed by a gradual 3- to 4-week taper appeared to be very well tolerated, with a low rate of premature discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events and no evidence of rebound anxiety during the taper. Few subjects reported benzodiazepine-related withdrawal symptoms; however, this observation must be interpreted with caution, as a specific instrument to elicit subtle withdrawal symptoms31 was not used in this study. Additionally, given the naturalistic treatment setting, it is likely that some number of subjects who were lost to follow-up experienced adverse events that dissuaded them from continued study participation.

The findings of the current study are consistent with results from two smaller, placebo-controlled trials in which combined treatment with a benzodiazepine and SSRI produced a more rapid stabilization of panic symptoms than SSRI alone.18,19 It is difficult, however, to compare across studies the magnitude of benefit of combination therapy, since the earlier trials used the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS)32 for primary efficacy analyses, an instrument which was not available in a validated self-rated form for use in this trial. It also was not possible to determine in the present study whether combination treatment with an SSRI/SNRI and alprazolam ODT reduced the frequency of panic attacks relative to treatment with SSRI/SNRI alone, as the IVRS assessed only the dichotomous presence or absence of attacks in the preceding week. Previous results from a large, placebo-controlled trial have shown that, compared with placebo, alprazolam is associated with a significant reduction in panic attack frequency as early as the first week of treatment, whereas antidepressant (imipramine) treatment did not significantly reduce the frequency of panic attacks until Week 6.33

Other limitations of the current study include its open-label design and lack of placebo control. That is, both investigators and subjects were aware of the medication regimen to which subjects were assigned. It is, therefore, possible that assignation to receive alprazolam ODT in combination with an SSRI/SNRI was associated with an increased expectation of good response compared with assignment to receive an SSRI/SNRI alone, and that the observed benefit reflects this non-specific investigator/subject expectation rather than specific medication effects. If this were the case, however, the expectation of greater efficacy would likely persist throughout the treatment period, or an expectation of loss of efficacy might be introduced once the alprazolam ODT taper had begun. As in the earlier trials,18,19 the differential benefit between combination therapy and monotherapy did not persist beyond the initial weeks of treatment; however, the early treatment gains in overall reductions in anxiety symptoms were maintained throughout the taper period.

The mean doses of alprazolam ODT used in this study tended toward the lower end of the therapeutic dose range for panic disorder,9 and, on the basis of therapeutic equivalence, were lower than the doses of clonazepam used in placebo-controlled trials demonstrating an early benefit of combination treatment with benzodiazepine and SSRI.18,19 Some of the antidepressant doses also tended toward the lower end of their recommended ranges. Although a cautious approach to dosing may be more representative of routine clinical practice that this study sought to evaluate, it is possible that higher doses of alprazolam ODT might have resulted in even more robust efficacy in early amelioration of target symptoms without substantial added side effect burden. This hypothesis could be tested in future studies using treatment algorithms to characterize a dose response relationship, although such an approach is arguably less generalizable than results obtained under purely naturalistic conditions. Nonetheless, the early clinical benefits observed in this study with low dose alprazolam ODT added to an SSRI/SNRI underscores the potential utility of combination regimens when initiating treatment of panic disorder.

Despite the use of relatively low doses of alprazolam ODT in this study, a considerable number of subjects did not complete the protocol-directed taper by Week 8. Unfortunately, specific reasons for unsuccessful taper were not elicited on subjects' case report forms. Thus, it is not clear whether those who did not complete the taper required continued treatment with alprazolam ODT to manage adverse effects of the prescribed SSRI/SNRI or to treat underlying anxiety in the case of SSRI/SNRI non-response. Alternatively, some individuals with panic disorder may simply require an extended period of down titration to avoid any distressing effects of benzodiazepine discontinuation. Taper failures might also be attributed to investigators' decisions to follow their standard clinical practice, which may have deviated from the protocol-directed taper over the last four weeks of the study. It is reassuring, however, that among subjects who did not complete the taper by Week 8, there was no evidence that increasing doses of alprazolam ODT were required. Further elucidation of an optimal dose range and length of taper to balance therapeutic benefits and adverse events of alprazolam ODT when used in combination with SSRIs/SNRIs would be welcome.

Future studies might also be directed toward establishing whether initiating treatment of panic disorder with the combination of an SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine, as was done in this trial, is preferable to short-term or “as needed” adjunctive treatment with a benzodiazepine to mitigate antidepressant-related adverse effects as they occur and/or to treat breakthrough symptoms.

In summary, initiating treatment of panic disorder with an SSRI/SNRI in combination with a brief course of alprazolam ODT, followed by a gradual taper, is safe and well tolerated, and may be associated with a more rapid onset of clinical improvement compared with SSRI/SNRI treatment alone. Such a regimen takes advantage of the rapid onset of anti-anxiety effect of alprazolam, and the safety of long-term treatment with SSRIs/SNRIs.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge each of the investigators who contributed data to this study, and Mary Susan Prescott, MS, who provided editorial assistance in development of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

David J. Katzelnick, Dr. Katzelnick is from Healthcare Technology Systems, Inc. and is Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin.

Johnaqa Saidi, Dr. Saidi is from Complete Care Medical Group Family Practice, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Mark R. Vanelli, Dr. Vanelli is from the Department of Psychiatry, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

James W. Jefferson, Dr. Jefferson is from Healthcare Technology Systems, Inc. and is Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin.

James M. Harper, Dr. Harper is from Department of Biometrics, Omnicare Clinical Research, King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.

Kay E. McCrary, Dr. McCrary is from Schwarz Pharma, Inc., Mequon, Wisconsin.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Revision (DSM-IV-R) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon WJ. Clinical practice: Panic disorder. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:2360–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp052466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al. The epidemiology of DSM-IV panic disorder and agoraphobia in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:363–74. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leon AC, Olfson M, Broadhead WE, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in primary care. Implications for screening. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:857–61. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.10.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA. 1995;274:1511–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitte K. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of psycho- and pharmacotherapy in panic disorder with and without agoraphobia. J Affect Disord. 2005;88:27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Work Group on Panic Disorder. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(5 Suppl):1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy-Byrne P, Stein M, Bystrisky A, et al. Pharmacotherapy of panic disorder: Proposed guidelines for the family physician. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:282–90. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.11.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stahl SM, Gergel I, Li D. Escitalopram in the treatment of panic disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1322–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollack MH, Otto MW, Worthington JJ, et al. Sertraline in the treatment of panic disorder: A flexible-dose multicenter trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1010–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wade AG, Lepola U, Koponen HJ, et al. The effect of citalopram in panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:549–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.6.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballenger JC, Wheadon DE, Steiner M, et al. Double-blind, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study of paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:36–42. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradwejn J, Ahokas A, Stein DJ, et al. Venlafaxine extended-release capsules in panic disorder: Flexible-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:352–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louie AK, Lewis TB, Lannon RA. Use of low-dose fluoxetine in major depression and panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:435–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruce SE, Vasile RG, Goisman RM, et al. Are benzodiazepines still the medication of choice for patients with panic disorder with or without agoraphobia? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1432–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:681–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.7.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:276–82. doi: 10.1177/02698811030173009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobak KA, Taylor LH, Dottl SL, et al. A computer-administered telephone interview to identify mental disorders. JAMA. 1997;278:905–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, et al. Computerized assessment of depression and anxiety over the telephone using interactive voice response. MD Comput. 1999;16:64–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, et al. Computer-administered clinical rating scales. A review. Psychopharmacology. 1996;127:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s002130050089. (Berl) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalbfleish JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1980. pp. 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winer BJ. Statistical Principles in Experimental Design. Second Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landis JR, Heyman ER, Koch GG. Average partial association in three-way contingency tables: a review and discussion of alternative tests. Inter Stat Rev. 1978;46:237–54. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. Second Edition. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1980. pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW, et al. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: A 12-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1179–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rickels K, Case WG, Schweizer E, et al. Benzodiazepine dependence: Management of discontinuation. Psychopharm Bull. 1990;26:63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, et al. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1571–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cross-National Collaborative Panic Study, Second Phase Investigators. Drug treatment of panic disorder: Comparative efficacy of alprazolam, imipramine, and placebo. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:191–202. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]