Abstract

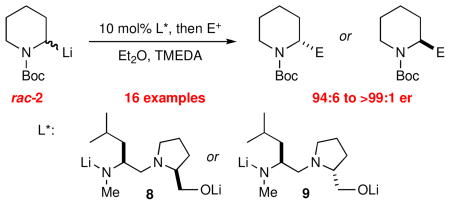

The catalytic dynamic resolution (CDR) of rac-2-lithio-N-Boc-piperidine using chiral ligand 8 or its diastereomer 9, in the presence of TMEDA has led to the highly enantioselective syntheses of either enantiomer of 2-substituted piperidines using a wide range of electrophiles. The CDR has been applied to the synthesis of R- or S-pipecolic acid derivatives, (+)-β-conhydrine, (S)-(+)-pelletierine, (S)-(−)-ropivacaine, and formal synthesis of (−)-lasubine II and (+)-cermizine C.

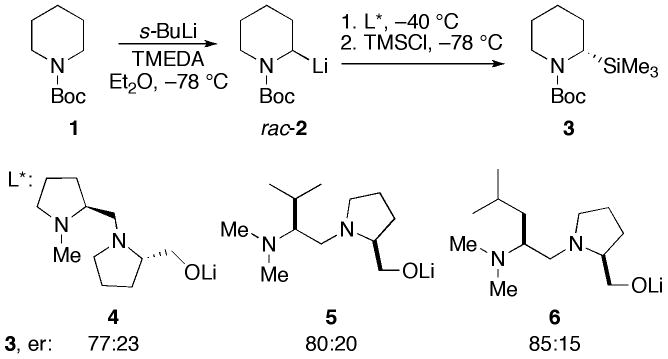

2-Substituted piperidines are found in many alkaloids and medicinal compounds which are derived from pipecolic acid. In 1989, Beak showed that racemic members of this class of compounds can be conveniently prepared by deprotonation and electrophilic quench of N-Boc-piperidine, 1, using s-BuLi and N, N, N′, N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA).1 Although the chiral base s-BuLi/(−)-sparteine efficiently and enantioselectively deprotonates N-Boc-pyrrolidine,2 the same base complex is less effective with N-Boc-piperidine.3 Partial success has recently been reported using O’Brien’s (+)-sparteine surrogate, which affords up to 88:12 er (R:S) in variable yields (depending on the electrophile), but this method is limited to one enantiomer.4

An alternative approach is the use of dynamic resolutions, and the most successful results to date for resolution of 2-lithio piperidines have been reported by the Coldham group.5 In dynamic thermodynamic resolutions (DTRs), chiral ligands coordinate to the metal of a chiral organolithium causing it to undergo carbanion inversion at a selected temperature, and populate one stereoisomer through equilibration. Upon cooling to freeze the equilibrium, reaction with an electrophile gives enantioenriched products.6 Coldham recently reported that N-Boc-2-lithiopiperidine 2 can be resolved by DTR using several monolithiated diamino alkoxide ligands (Scheme 1).5

Scheme 1.

DTR of N-Boc-2-lithiopiperidine 2.5

A catalytic dynamic resolution (CDR) of 2-lithio-N-trimethylallylpyrrolidine was recently reported.7 We now report the discovery of a CDR of rac-2 using new ligands that afford excellent enantioselectivity, for either enantiomer of 2-substituted piperidines.

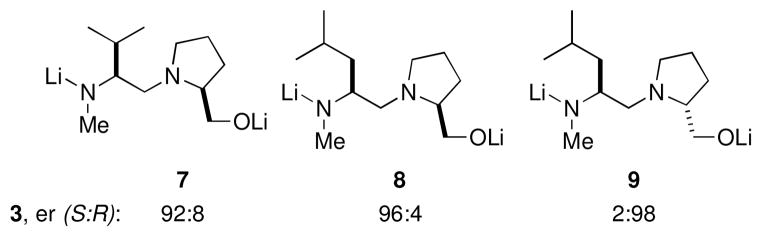

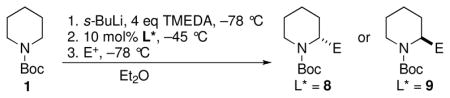

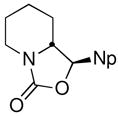

In their report on the stoichiometric DTR of rac-2, Coldham, et al, indicated that the resolution is facilitated by the addition of lithium isopropoxide.5 With this in mind, we investigated the enantioselectivity of dilithio diaminoalkoxides 7–9 in a stoichiometric DTR using the Coldham conditions. We were gratified to find the high er’s shown in Figure 1. Note that diastereomeric ligands 8 and 9 afford very high er, and opposite configurations of 3.

Figure 1.

Dilithio ligands for dynamic resolution.

A successful CDR depends on several factors, including a lower barrier for DTR than for racemization at a given temperature.8 A plot of ΔG‡ vs. temperature for racemization of 2 in the presence of TMEDA and DTR of 2·8 in the presence of TMEDA revealed that the barrier for DTR is lower than for racemization below −27 °C (see Supporting Information). Thus a CDR was attempted by generating the racemic organolithium 2 by deprotonation in Et2O at −78 °C with s-BuLi/TMEDA, followed by addition of 10 mol% of 8, warming to −45 °C for three hours, then cooling to −78 °C and quenching with Me3SiCl. We were gratified to obtain 3 in 74% yield and 96:4 er (Table 1, entry 1). Several other electrophiles were evaluated under the same CDR conditions, with the results summarized in Table 1, entries 2–14. Excellent enantiomer ratios and good yields were obtained in all cases. Procedures to recover the chiral ligand are included in the SI.

Table 1.

CDR of 2 at −45 °C for 3 h using ligand 8 (or 9 where noted).

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | E+ | Product(s) | % Yield | er |

| 1 | Me3SiCl | (S)-3 | 74 | 96:4 |

| 2 | Bu3SnCl | (S)-10 | 66 | 96:4 |

| 3 | Bu3SnCl | (R)-10 | 62 | 97:3a |

| 4 | CO2 | (R)-11 | 78 | 98:2 |

| 5 | MeOCOCl | (R)-12 | 88 | >99:1 |

| 6 | MeOCOCl | (S)-12 | 85 | >99:1a |

| 7 | PhNCO | (R)-13 | 68 | >99:1 |

| 8 | Allyl bromide | (R)-14 | 63 | 95:5b |

| 9 | Allyl bromide | (S)-14 | 59 | 96:4a,b |

| 10 | BnBr | (R)-15 | 65 | >99:1b |

| 11 | Cyclohexanone |

(R)-16 |

60 | 94:6 |

| 12 | PhCHOc |

17 |

74 (62:38 dr) | >99:1 & 98:2 |

| 13 | 1-NpCHOc |

18 |

66 (82:18 dr) | 94:6 & 93:7 |

| 14 | CH3CHOc |

19 |

78 (85:15 dr) | >99:1 for both |

Using ligand 9

via Negishi cross coupling

Major diastereomer illustrated

CDR using ligand 8 and quenching with Bu3SnCl afforded (S)-10 in 66% yield and 96:4 er. With ligand 9, (R)-10 was obtained in 62% yield and 97:3 er. When CO2 was used as electrophile, N-Boc-(R)-(+)-pipecolic acid, (R)-11, was obtained in 78% yield and 98:2 er using 8. Quenching with ClCO2Me afforded enantiopure methyl pipecolate ester (R)-12 using ligand 8 and (S)-12 using ligand 9. Reaction with PhNCO afforded enantiopure anilide (R)-13 using ligand 8.

The electrophilic bimolecular substitutions discussed above (entries 1 to 7), proceed via a polar pathway, presumably with retentive substitution at the metal bearing carbon (SE2ret).9 However, when (S)-2 was trapped directly with either allyl chloride or benzyl bromide, nearly racemic products were obtained. These nonselective reactions probably proceed through a single electron transfer (SET) pathway.10 The enantioselectivity of the allylations was therefore evaluated under Negishi conditions, which have been successfully applied in this system,4 whereby 2 is transmetalated with ZnCl2 and coupled using CuCN·2LiCl. Under these conditions, allyl bromide afforded (R)-14 with ligand 8 in 63% yield and 95:5 er (entry 8). When CDR using ligand 9 was employed, (S)-14 was obtained in 59% yield and 96:4 er (entry 9). A similar protocol using ligand 8 and Negishi coupling with benzyl bromide gave enantiopure (R)-15 in 65% yield (entry 10).

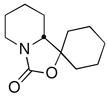

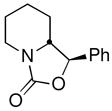

CDR of rac-2, followed by addition to aldehydes and ketones was also investigated, with the results summarized in Table 1, entries 11–14. Not surprisingly,11 the adducts from addition to cyclohexanone, benzaldehyde, and 1-naphthaldehyde cyclized, in situ, to oxazolidinones, the latter two as mixtures of diastereomers. Nevertheless, the configuration at the lithium-bearing carbon of 2 was maintained, with all adducts exhibiting high er’s. Quenching with acetaldehyde provides a convenient way to prepare the enantiopure alcohol 19 in 78% yield as a mixture of diastereomers (85:15 dr, entry 14).

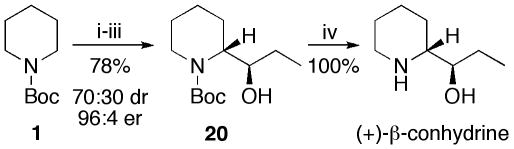

When (S)-2 was quenched with propionaldehyde, the alcohol 20 was obtained as a 70:30 mixture of diastereomers, both of which had 96:4 er. Separation of the diastereomers by column chromatography and hydrolysis of the carbamate from the major diastereomer afforded the alkaloid (+)-β-conhydrine (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of (+)-β-conhydrine

i) s-BuLi (1.2 equiv), Et2O, TMEDA (4.0 equiv), –78 °C, 3 h; ii) 8, (10 mol%), –45 °C, 3 h; iii) EtCHO, –78 °C, 2 h; iv) CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2.

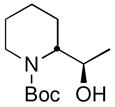

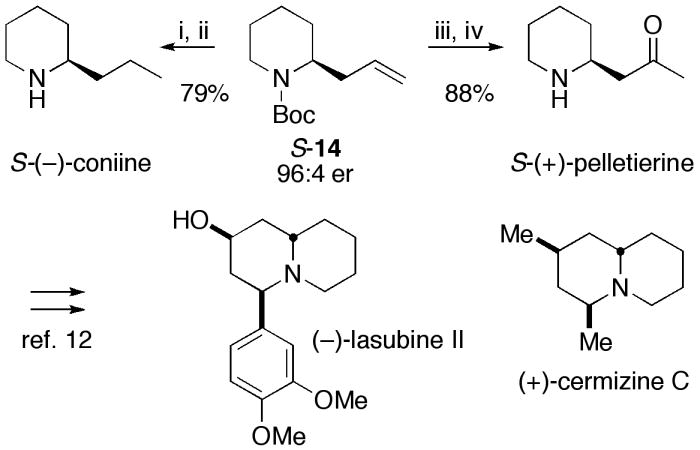

Hydrogenation of (S)-14 and deprotection afforded (S)-(−)-coniine; Wacker oxidation and deprotection afforded (S)-(+)-pelletierine (Scheme 3). Cheng and coworkers have recently prepared (S)-14 from glutaraldehyde in 6 steps, and showed that (S)-14 can be readily converted to (−)-lasubine II and (+)-cermizine C via (S)-(+)-pelletierine.12

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of (S)-(+)-pelletierine and (S)-(−)-coniine. Formal synthesis of (−)-lasubine II and (+)-cermizine C.12

i) Pd(OH)2 (1.0 eq), H2 (1 atm), MeOH, rt, 48 h; ii) CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 2 h, then NaOH, pH 10; iii) PdCl2 (1.0 eq), CuCl (10 mol%), O2, DMF/H2O (10:1), rt, 10 h; iv) CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 2 h, then NaOH.

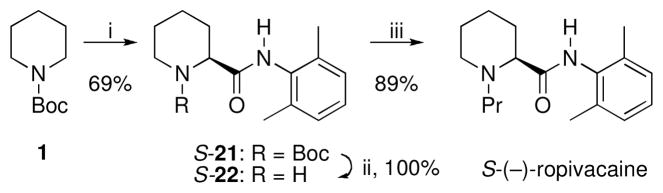

CDR of 2 with ligand 9 and electrophilic quench with 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanate afforded enantiopure (>99:1 er) (S)-21 in 69% yield (Scheme 4). After deprotection, alkylation with 1-bromopropane in the presence of K2CO3 yielded (S)-(−)-ropivacaine in three overall steps and 61% overall yield.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of (S)-(−)-Ropivacaine

i) s-BuLi (1.2 eq), Et2O, TMEDA (4.0 eq), −78 °C, 3 h, then 9, (10 mol%), −45 °C, 3 h, −78 °C, 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanate, 2 h, >99:1 er; ii) CF3COOH, CH2Cl2, rt, 10 h, then NaOH; iii) isopropyl alcohol, 1-bromopropane (3.0 equiv), K2CO3 (3.0 equiv), H2O, 100 °C, 6 h.

In summary, the discoveries of ligands 8 and 9 coupled with their ability to resolve N-Boc-2-lithiopiperidine catalytically have provided an efficient route for the highly enantioselective syntheses of 2-substituted piperidines of either absolute configuration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Arkansas Biosciences Institute and the National Science Foundation (CHE 0616352 and 1011788). Core facilities were funded by the National Institutes of Health (R15569) and the Arkansas Biosciences Institute. The authors are grateful to Professors Dieter Seebach and Iain Coldham for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Full experimental details and spectroscopic data. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Beak P, Lee WK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:1197. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerrick ST, Beak P. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9708. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey WF, Beak P, Kerrick ST, Ma S, Wiberg KB. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1889. doi: 10.1021/ja012169y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stead D, Carbone G, O’Brien P, Campos KR, Coldham I, Sanderson A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7260. doi: 10.1021/ja102043e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coldham I, Raimbault S, Chovatia PT, Patel JJ, Leonori D, Sheikh NS, Whittaker DTE. Chem Commun. 2008:4174. doi: 10.1039/b810988e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Lee WK, Park YS, Beak P. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:224. doi: 10.1021/ar8000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Coldham I, Sheikh NS. In: Topics in Stereochemistry. Gawley RE, editor. Vol. 26. VHCA; Zürich: 2010. p. 253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beng TK, Yousaf TI, Coldham I, Gawley RE. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6908. doi: 10.1021/ja900755a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.A mechanistic study of the DTR and CDR of rac-2 will be published elsewhere.

- 9.Gawley RE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4297. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Rein KS, Chen ZH, Perumal PT, Echegoyen L, Gawley RE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:1941. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gawley RE, Low E, Zhang Q, Harris R. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3344. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gawley RE, Eddings DB, Santiago M. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:4285. doi: 10.1039/b608013h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beak P, Lee WK. J Org Chem. 1993;58:1109. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng G, Wang X, Su D, Liu H, Liu F, Hu Y. J Org Chem. 2010;75:1911. doi: 10.1021/jo902615u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.