Abstract

This paper examines the effect of a student’s own school adjustment as well as the contextual level of school adjustment (the normative level of school adjustment among students in a school) on student's self-reported use of alcohol. Using a dataset of 43,465 male and female 8th grade students from 349 schools across the contiguous United States who participated in a national study of substance use in rural communities between 1996 and 2000, multilevel latent covariate models were utilized to disentangle the individual-level and contextual effects of three school adjustment variables (i.e., school bonding, behavior at school, and friend’s school bonding) on alcohol use. All three school adjustment factors were significant predictors of alcohol use both within and between schools. Furthermore, this study demonstrated a strong contextual effect; students who attended schools where the overall level of school adjustment was higher reported lower levels of alcohol use even after taking their own school adjustment into account. The results demonstrate the importance of both a student’s own level of school adjustment and the normative level of school adjustment among students in the school on an adolescent’s use of alcohol. Differences in school adjustment across schools were quite strongly related to an adolescent's own alcohol use, indicating that school adjustment is an important aspect of school climate. Initiatives aimed at improving school climate may have beneficial effects on students’ alcohol use.

Keywords: alcohol use, adolescents, peers, school adjustment, contextual effects, rural, multilevel latent covariate model

INTRODUCTION

The school environment has been described as one of the most influential socialization domains in an adolescent’s life (Catalano, Haggerty, Oesterle, Fleming, & Hawkins, 2004). Several decades of research have demonstrated that a student’s experiences at school and adjustment to school can exert both positive and negative influences on their development. These influences extend beyond school-specific behavior (e.g., academic performance, attendance at school) to prosocial and antisocial development in general, including early involvement with alcohol use.

Ample evidence (reviewed below) suggests that a young student’s own positive school adjustment is a protective factor with respect to alcohol use. However, an individual student’s alcohol use may not only be affected by their own degree of school adjustment but may also be influenced by the degree to which their classmates demonstrate positive school adjustment. As described by Osgood and Anderson (2004), an individual-level variable (e.g., school bonding) may account for differences in alcohol use across schools in two ways – via a compositional effect and via a contextual effect. A compositional effect is simply the effect that would be expected because the students in a particular school have, on the average, better school adjustment than students in other schools, and the average level of alcohol use in that particular school would therefore be lower than in other schools. In other words, in schools where more of the students are well adjusted to school, fewer students will use alcohol. A contextual effect is different. It occurs when the general school environment, in this case, school adjustment, has an effect on individual student's use of alcohol above and beyond what would be expected based on his or her own level of school adjustment. In other words, a significant contextual effect indicates that, given two students who demonstrate the same level of school adjustment but attend two different schools, the student attending a school where pupils tend to be better adjusted to school will demonstrate less alcohol use than the student attending a school where pupils tend to be poorly adjusted to school. Osgood and Anderson (2004) indicate that “contextual effects are consequences of emergent properties of groups or social settings, and thus they cannot be accounted for at the individual-level (pg. 522).” Thus, a compositional effect occurs merely because it is an average of the individual effects, while a contextual effect is an influence of the general school environment on an individual.

While the effect of school adjustment on alcohol use has been well studied at an individual level, little research has assessed the compositional and contextual effects of school adjustment on alcohol use. Several recent papers have pointed out that, while it is known that social environments are clearly important, the relationship between school contexts and substance use has not been adequately explored (Eitle & Eitle, 2004; Maes & Lievens, 2003). In this paper, we address this understudied topic. Specifically, we apply an innovative methodology, multilevel latent covariate modeling (MLCM) (Ludtke, et al., 2008), to a dataset consisting of a national sample of rural schools. We assess the individual, compositional and contextual effects of school adjustment on student alcohol use.

Defining School Adjustment

Although the debate regarding the definition of school adjustment is ongoing, the concept of school adjustment has been broadened in recent years to consider outcomes beyond academic performance (Ladd, 1989, 1996; Libbey, 2004; Perry & Weinstein, 1998). Libbey (2004) provides a thorough review of the conceptualizations of attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement to school utilized in research over the past couple of decades. In an effort to incorporate as much of the existing theory and empirical evidence as possible (yet stay within the limits of what is possible with secondary data analysis), we consider three aspects of school adjustment – the individual’s level of school bonding, friend’s school bonds, (association with peers who are bonded to school), and avoidance of school-related misbehavior (e.g., cheating, skipping school).

The extent to which a student likes or enjoys school and is attached to teachers is a very commonly considered aspect of school adjustment (Eccles, Early, Frasier, Belansky, & McCarthy, 1997; Goodenow & Espin, 1993; Hawkins, Guo, Hill, Battin-Pearson, & Abbott, 2001; Ladd, 1989; Samdal, Nutbeam, Wold, & Kannas, 1998; Simons-Morton & Crump, 2003; Simons-Morton, Crump, Haynie, & Saylor, 1999) and is often referred to as school bonding. Friend’s school bonding is considered because the social development model (Catalano, et al., 2004; Hawkins & Weis, 1985) and peer cluster theory (Oetting & Beauvais, 1987) clearly indicate the importance of bonding to peers and indicate that bonding to peers with prosocial attitudes, including positive attitudes toward school, supports prosocial behaviors. Finally, school related misbehavior or disruptive behavior is a construct that also has been used to conceptualize a student’s overall level of school adjustment (Ryan & Patrick, 2001).

School Adjustment and Adolescent Alcohol Use

Primary socialization theory (Oetting & Donnermeyer, 1998) and the social development model (Catalano, et al., 2004; Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985) offer theoretical frameworks to describe the mechanisms by which positive school adjustment may protect a young adolescent from engagement in alcohol use. Both models are related to the theoretical underpinnings of social control theory (Hirschi, 1971), differential association theory (Matsueda, 1988), and social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) (Fleming, Catalano, Oxford, & Harachi, 2002). The models posit that children learn patterns of behavior from primary socialization sources, including school, family, and peer groups. To the extent that children and adolescents are bonded or attached to pro-social primary socialization sources, their involvement in deviant behavior, including drug use and precocious alcohol use, is attenuated because they are motivated to conform to the norms, expectations, and values of the pro-social sources.

On the other hand, weak bonds to pro-social sources and strong bonds to antisocial sources free young people from adhering to conventional norms that discourage alcohol use, and affected youth are more likely to follow the norms, expectations, and values of antisocial sources (e.g., friends who are not strongly bonded to school). In sum, students with strong school bonds are more likely to delay onset of alcohol use and less likely to escalate use of alcohol (Maddox & Prinz, 2003; Shears, Edwards, & Stanley, 2006).

School Context and Adolescent Alcohol Use

Several theories provide a solid theoretical framework for expecting that the normative school environment with regard to school adjustment factors is an important predictor of substance use and other forms of delinquency. The social development model (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985) hypothesizes that young people learn both pro-social and antisocial patterns of behavior (including use of alcohol) from the school environment. Furthermore, the behavior of an individual student will be pro-social or antisocial (e.g., avoiding or engaging in alcohol use) as a function of the prominent norms, attitudes, and behaviors demonstrated by the school culture. There is some empirical work to support this hypothesis (Battistich & Hom, 1997; Cleveland & Wiebe, 2003; Frankowski, et al., 2007; Henry & Slater, 2007; Kim & McCarthy, 2006).

Drawing from the sociological literature, Elliott and colleagues' integrated perspective on delinquent behavior provides a framework for understanding how one’s environment may influence alcohol use (Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985; Elliott, Ageton, & Canter, 1979). They indicate that risk factors in one’s environment weaken an individual’s bond to conventional, prosocial society. Welsh’s (2000) studies of school climate corroborate this theoretical framework. He asserts that schools, like individuals, have their own characteristic personalities (e.g., climates), describing climate as “the feel of the school as perceived by those who work there or attend class there…the general ‘we feeling’ and interactive life of the school (pg. 92).” Furthermore, Welsh points to Owens’ (1987) works on organizational behavior in education, indicating that the aggregated perceptions of individuals at the school (e.g., students, teachers) comprise the construct of school climate. Research has confirmed that school climate factors such as school belonging, school attachment, and sense of school as a community do vary significantly across schools (Anderman, 2002; Battistich & Hom, 1997; Henry & Slater, 2007) and Welsh (2000; Welsh, Greene, & Jenkins, 1999) indicates that negative school climates can and do exhibit a negative influence on students’ behavior.

Framework for the current study

Building on the empirical and theoretical support for individual and contextual effects of school adjustment factors, this study seeks to determine the extent to which the contextual effect of several school adjustment variables affect alcohol use, beyond or in addition to the effect of a student’s own level of school adjustment. This study builds on previous investigations of school-related contextual effects in that it assesses several different school adjustment factors, uses a very large sample of schools across rural America (a population that is understudied), and employs a novel and innovative statistical methodology.

METHODS

Sample

Participants in this study are 43,465 male and female 8th grade students from 349 schools across the contiguous United States who participated in a national study of substance use in rural and non-rural communities between 1996 and 2000. The sample was constructed to, as closely as possible, yield a stratified, representative, sample of rural schools in the contiguous U.S. Predominantly Mexican-American and African-American communities were oversampled to allow comparisons by ethnicity.

Non-metropolitan (e.g., rural) counties within each of the four FBI crime report regions (West, South, Midwest, Northeast) were classified into four groups (based on 1990 census data) based on population and proximity to a metropolitan area. The level of rurality was further refined by adding accessibility in travel time. A rural community that is very small may, in fact, have easy access to a larger metropolitan community, making it less rural than its population and/or its miles from the larger area would seem to indicate. Because census data do not report distances to major services and travel times to larger population centers, questions measuring accessibility were asked in community assessment surveys. Questions included miles from an interstate exit, drive time to nearest metropolitan area, and distance and obstacles to driving to the nearest big town. Communities were then classified into four levels of rurality: remote, medium rural, small urban, and large urban. A remote community has a population less than 2,500 and is located more than 2 hours driving time from a metropolitan area. A medium rural community either has a population between 2,500 and 20,000 or a population less than 2,500 but is located less than 2 hours driving time from a metropolitan area. A small urban community has a population between 20,000 and 50,000, while a large urban community has a population greater than 50,000.

Where possible, predominantly White communities (defined as over 60% white population) within each of the rurality categories were drawn in proportion to their representation in each of the four regions and each state within those regions. Where it was not possible to match representation for a given state (due to problems in legislative restrictions of the protocol for informed consent or other recruiting difficulties), matched communities in nearby states within the same region were substituted.

Ethnic minority communities were defined as those that included 40% or more Mexican Americans or 40% or more African Americans. Essentially all rural Mexican-American communities are located in the Southwestern U.S.; therefore, the Mexican-American communities within each of the rurality categories were drawn from states in the Southwest in proportion to their representation in those states. The African-American communities were selected in the same way from the Southeastern states that include those communities.

Within each community, surveys were administered at a single public high school and the public junior-high/middle school or schools that were feeders for that school. The sample used in the present analyses consists of these 8th grade students. In the relatively small percentage of cases where there was more than one high school in the community, the high school determined to be the most representative socio-demographically of the community and its feeder schools was chosen.

Procedure

Anonymous surveys were given with passive parental consent, and procedures ensured complete confidentiality. Across schools, the percent of students surveyed ranged from 75–100% of the total student body. In order to ensure that the self-reported data was reasonably trustworthy and represented an accurate picture of the respondents’ behaviors and attitudes, 40 different internal consistency checks were made on each completed survey prior to using the survey data for analyses (e.g., indicating no lifetime use of marijuana but reporting use of marijuana in the last month, endorsement of a fake drug, or illogical estimates of relative harm of drug use). If there were three or more inconsistencies the student’s survey was discarded. Approximately 1% of surveys were discarded for inconsistent responses.

Instrument and Measures

Students were given the Community Drug and Alcohol Survey (CDAS)1. The CDAS is a 99-item survey that asks a variety of questions related to substance use; school adjustment; relationships with family and peers; and other individual risk factors for substance use. Its measures have been through rigorous reliability and validity analysis (Oetting & Beauvais, 1990–1991), and it is one of the instruments listed in SAMHSA’s Measures and Instruments Resource guide.

The dependent variable, alcohol use, was measured with 4 indicators: 1.) “How often in the last month have you had alcohol to drink?” (none, 1–2 times, 3–9 times, 10–19 times, 20 or more times), 2.) “How often in the last month have you gotten drunk?” (same scale as previous item), 3.) “In using alcohol, are you a…?” (non user, very light user, light user, moderate user, heavy user, very heavy user), 4.) “How do you like to drink?” (I don’t drink, just a glass or two, enough to feel it a little, enough to feel it a lot, until I get really drunk). The alcohol use score was obtained by first standardizing each item to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, and then computing the mean of the four items. Coefficient alpha equals .91.

The independent variables include three school adjustment constructs: school bonding, friend’s school bonding, and behavior at school. School bonding was measured with four indicators that, in combination, assess a student’s fondness for school and bonding to teachers. The items include: “I like school”, “School is fun”, “I like my teachers”, and “My teachers like me.” The items were measured on a four point scale ranging from “not at all” to “a lot.” Coefficient alpha equals .87. Friend’s school bonding was defined with three indicators: “Do your friends…1.) like school?”, 2.) “like their teachers?”, and 3.) “think school is fun?” All three items were measured on a four-point ranging from “not at all” to “a lot.” Coefficient alpha equals .89. Finally, behavior at school was measured with two items, “I cheat in school,” “I do things my teachers don’t want me to do.” Both were measured on a four-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “a lot” and were reverse coded for analysis. Coefficient alpha equals .62. For all school adjustment constructs, a scale was formed by taking the average of the indicators.

Several control variables were used at each level. Within schools, we included age, gender (coded as 1 for boys and 0 for girls), and race/ethnicity (dummy coded to compare White students to African American, Mexican American, and students of some other ethnicity respectively). Between schools, we included several variables collected from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) database, including the number of students in the school, the percent of students in the school who received free or reduced lunch, the pupil to teacher ratio, and a dichotomous variable to indicate whether or not the 8th graders were in the same school as high school students. In addition, we included the average age of the 8th grade students who were surveyed, the percent of students in the school who were White, the year that the survey took place (represented as dummy variables to compare 1996 to 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2000 respectively), the level of rurality of the community (represented as dummy variables to compare remote communities to medium rural, small urban, and large urban communities respectively), and two indicators to compare predominantly African American communities (where at least 40% of the residents were African American) and predominantly Mexican-American communities (where at least 40% of the residents were Mexican-American) to predominantly White communities (over 60% White).

Analysis

Multilevel models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) were used to assess the hypotheses of interest. This type of analysis is appropriate because the data collection procedures employed cluster sampling (i.e., students were nested in schools) and because the primary hypotheses of interest concerned the effect of individual and contextual manifestations of school adjustment on students’ use of alcohol.

Traditionally, contextual effects of an individual level variable have been assessed by forming an aggregated mean (e.g., the average level of school bonding of students in a school) and then including this aggregated mean in the level 2 (e.g., school level) model (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). While this traditional approach of decomposing variance to test for contextual effects could have been used to examine the proposed hypotheses, we instead employ a novel and innovative analytic method called multilevel latent covariate modeling (MLCM) (Ludtke, et al., 2008). In this approach the compositional manifestation of each school adjustment variable is modeled as a latent variable.

Simulation studies demonstrate that this approach is superior to the traditional method described by Raudenbush and Bryk (2002). This is because the traditional approach assumes that there is no measurement error in the resultant aggregated mean. That is, that the aggregated mean (e.g., the average level of school bonding among students in a school) is the true and correct indicator of the normative or compositional level of school bonding. As demonstrated by Ludtke and colleagues (2008), the aggregated mean is an approximation of the “true” mean and is often not very reliable. To the extent that the aggregated mean is an unreliable measure of the true group mean, then the estimates of the compositional and contextual effects will be biased. However, the MLCM approach models the between unit variable as a latent variable and Ludtke and colleagues simulations show that this approach results in superior estimates. The between unit variable (e.g., the between unit school bonding variable) is latent in the sense that it may be considered to exist but cannot be directly measured, rather, it must be inferred from the data (e.g., inferred from the individual reports of school bonding from each surveyed student in the school). This approach is akin to modeling a multiple item scale as a latent variable in a structural equation modeling framework rather than taking the mean of the items.

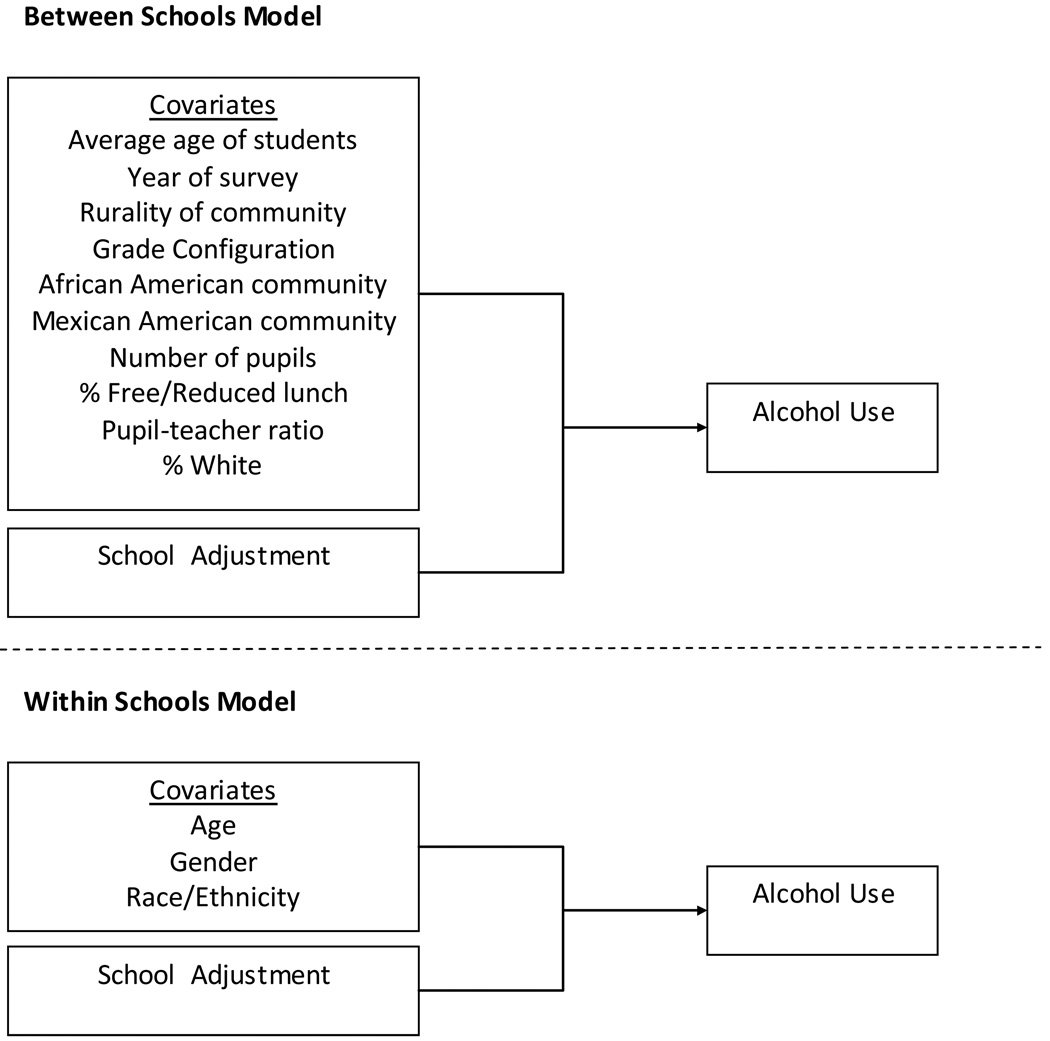

As a result of this innovation, we were able to use MLCM to decompose the school adjustment variables into their respective within and between school components (i.e., Are there differences between students within schools and are there differences between schools?) We were further able to decompose the between school component into the compositional and contextual effect on alcohol use. The contextual effect is derived by subtracting the within schools effect from the compositional effect. All analyses were conducted in Mplus, Version 5.2 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2008). Robust standard errors were employed in order to account for the skewed nature of the alcohol use variables. In order to properly account for missing data (due to some students skipping items and or not completing the entire survey), we created ten multiple imputations in SAS, version 9.3. All variables (i.e., all covariates (both within school and between school), school adjustment measures, drug use, and potential interactions) were included in the imputation model. Each model was estimated across each of the ten imputed datasets, and the results were combined using the procedures outlined by Rubin (1987). Figure I presents a simplified example diagram of the full models that were tested to assess each school adjustment variable of interest.

Figure I.

Simplified diagram of the tested Multilevel Structural Equation Models

RESULTS

Table I presents the descriptive statistics for the school adjustment variables and the alcohol score. We also report the intraclass correlation (ICC), which indicates what proportion of the total variance of a variable occurs between schools. For example, the ICC for alcohol use indicates that about 5.0% of the variance of students’ alcohol use lies between schools. The ICC’s for the school adjustment variables vary between 4.5% (for behavior at school) to 5.7% (friend’s school bonding). These values indicate that most of the variance occurs because of differences between individual students; however, enough variance exists between schools to allow for analysis of multilevel research questions.

Table I.

Within and between-school means (M), standard deviations (SD), and intraclass correlations (ICC)

| Within School |

Between School |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ICC | |

| School Bonding | 0.00 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 5.1% |

| Behavior at School | 0.00 | 0.79 | −0.03 | 0.17 | 4.5% |

| Friends' School Bonding | 0.00 | 0.78 | −0.01 | 0.19 | 5.7% |

| Alcohol Use | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 5.0% |

Table II presents the within school and between school correlation matrix for the school adjustment variables and alcohol use. The within school correlations are presented on the lower diagonal and the between school correlations are presented on the upper diagonal. As expected, we see moderate to large positive correlations for the school adjustment variables both within schools and between schools. We also see moderate negative within school correlations between alcohol use and the school adjustment variables and large negative between school correlations between alcohol use and the school adjustment variables.

Table II.

Within and between-school correlations of school adjustment variables and alcohol use

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. School Bonding | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.91 | −0.57 |

| 2. Behavior at School | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.55 | −0.74 |

| 3. Friends' School Bonding | 0.67 | 0.29 | 1.00 | −0.59 |

| 4. Alcohol Use | −0.29 | −0.38 | −0.24 | 1.00 |

Notes: Within school correlations are on the lower diagonal and between school correlations are on the upper diagonal.

Next, we estimated a baseline model (Model 1) that included only alcohol use and the control variables. The intercept and all level 1 covariates (age, gender, and race/ethnicity) were specified as random effects. The parameter estimates for the regression of alcohol use on the control variables are presented in Table III. The parameter estimates represent each variable’s effect after adjusting for all other variables in the model. All of the within school effects (i.e., the student-level variables) were statistically significant. Older students and males reported higher alcohol use. In addition, Mexican American students, and students reporting an ethnic background other than White, Mexican American or African American reported higher alcohol use (compared to White students) while African-American students reported lower alcohol use (compared to White students). In addition, two school-level variables (i.e., the between school effects) were significant predictors of alcohol use, average age of the surveyed students (a higher average age was associated with higher levels of alcohol use) and percent of students in the school who were White (holding all other variables constant, a higher percentage of White students was associated with a lower level of alcohol use). We calculated the within school and between school R2 using the formulas offered by Snijders and Bosker (1999), these estimates indicate that 4.0% of the variance in the level 1 alcohol scores (individual alcohol use) and 27.0% of the variance in level 2 alcohol scores (i.e, mean alcohol use across schools) were predicted by the covariates in Model 1.

Table III.

Parameter estimates for the initial multilevel structural equation model (Model 1)

| Est | SE | ||

| Fixed Effects | |||

| Intercept | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Within School Effects | |||

| Age | 0.20 | 0.00 | ** |

| Male | 0.07 | 0.00 | ** |

| Other ethnicity (compared to White) | 0.13 | 0.02 | ** |

| African American (compared to White) | −0.10 | 0.01 | ** |

| Mexican American (compared to White) | 0.18 | 0.02 | ** |

| Between School Effects | |||

| Number of pupils in school | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Percent of students who receive free/reduced lunch | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Pupil to teacher ratio | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Proportion of students in school who are White | −0.16 | 0.08 | * |

| Average age of study participants | 0.12 | 0.05 | ** |

| Eighth grade students in the high school | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| School surveyed in 1997 (compared to 1996) | 0.08 | 0.06 | |

| School surveyed in 1998 (compared to 1996) | 0.02 | 0.06 | |

| School surveyed in 1999 (compared to 1996) | −0.01 | 0.06 | |

| School surveyed in 2000 (compared to 1996) | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| Medium rural community (compared to remote community) | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Large rural community (compared to remote community) | −0.02 | 0.03 | |

| Metro community (compared to remote community) | 0.03 | 0.05 | |

| Predominantly African American community (compared to White community) | −0.07 | 0.04 | |

| Predominantly Mexican-American community (compared to White community) | −0.06 | 0.05 | |

| Random Effects | |||

| Intercept | 0.03 | ||

| Age | 0.01 | ||

| Male | 0.02 | ||

| Other ethnicity (compared to White) | 0.03 | ||

| African American (compared to White) | 0.03 | ||

| Hispanic (compared to White) | 0.04 | ||

| Within school residual | 0.72 |

Notes

R2 for alcohol scores: Level 1 (Individual)=4.0%, Level 2 (Schools)=27.0%

p<.05.

p<.01

With the control model developed, we next assessed three separate MLCMs (one for each school adjustment variable). In these models, alcohol use was regressed on all of the covariates reported in Table III (again allowing the intercept and the effects for age, gender, and race/ethnicity to vary across schools). In addition, alcohol use was regressed on the school adjustment variables in both the within schools and between schools model and the within school effect was specified as random. The results of the models are reported in Table IV. In order to conserve space, we present the regression parameters for only the effects of primary interest, including the within school effect of school adjustment (the expected difference in alcohol use between two students in the same school who differ by one unit on school adjustment), the compositional effect of school adjustment (the expected difference between the means of alcohol use for two schools that differ by one unit in their average school adjustment scores), and the contextual effect of school adjustment (the between schools effect minus the within school effect). The contextual effect represents the expected differences in alcohol use between two students who have the same personal level of school adjustment, but who attend schools differing by one unit in the average level of school adjustment among its students (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Table IV.

Within and between school effects of school adjustment variables on alcohol scores

| Within School Effect |

Between School Effect |

Contextual Effect |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | R2 | Est | SE | R2 | Est | SE | |

| School Adjustment Variables | ||||||||

| Model 2: School Bonding | ||||||||

| fixed effect | −0.33 | 0.01 ** | 12.5% | −0.51 | 0.07 ** | 45.8% | −0.19 | 0.07 ** |

| random effect | 0.013 | |||||||

| Model 3:Behavior at School | ||||||||

| fixed effect | −0.41 | 0.01 ** | 18.6% | −0.60 | 0.07 ** | 55.5% | −0.19 | 0.07 ** |

| random effect | 0.012 | |||||||

| Model 4: Friends' School Bonding | ||||||||

| fixed effect | −0.25 | 0.01 ** | 10.2% | −0.47 | 0.06 ** | 49.9% | −0.22 | 0.06 ** |

| random effect | 0.009 | |||||||

Notes

p<.01

After adjusting for pertinent covariates at the student level and school level, each of the three school adjustment scales had a significant negative effect on alcohol use within school. That is, students with stronger school bonding, those who avoided school misbehavior, and those with friend’s who had stronger school bonds, reported lower levels of alcohol use. Likewise, significant negative between schools effects were also observed for each of the three school adjustment variables and alcohol use.

Of most importance to the current analysis, a contextual effect for school adjustment on alcohol use was observed for each of the school adjustment variables. That is, adolescents who attended schools where students tended to have strong school bonds, avoided school-related misbehavior, and had friends with strong school bonds reported lower levels of alcohol use than would have been expected based on their own school adjustment.

Table IV also reports the R2 values for each model, indicating the percent of variance in alcohol use explained within schools and between schools. Avoidance of school-related misbehavior (labeled as “behaves at school” in Table IV) appears to be the most robust predictor, demonstrating an R2 of 18.6% at level 1 (individual level) and 55.5% at level 2 (school level). The control model predicted 4.0% of the level 1 variance and 27.0% of the level 2 variance; therefore, the school behavior construct explained an additional 15% of variance at level 1 and 29% of variance at level 2. While the change in R2 is largest for avoidance of school-related misbehavior, all other school adjustment variables also explained a significant proportion of variance both within and between schools.

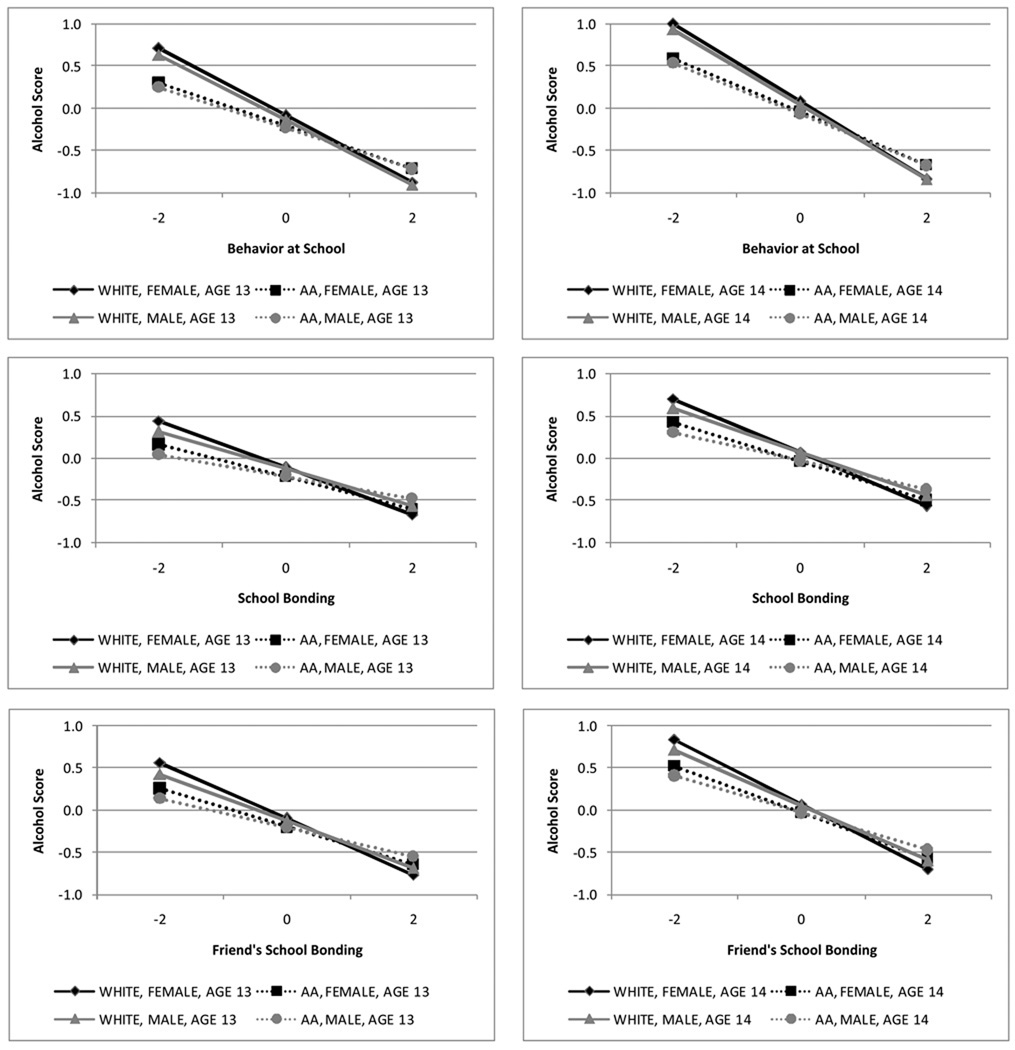

As a final step, we explored the possibility of interactions between school adjustment (at each level) and each of the level 1 (individual level) and level 2 (school level) covariates listed in Table III. Given the exploratory nature of these interaction analyses and the large number of interactions tested, we employed a Bonferroni correction to the p-values. Across the models, none of the cross level or school level interactions were statistically significant; however, several of the level 1 interactions were statistically significant (Figure 2). For school bonding, three level 1 interactions emerged -- age (b=−.05(.01), t=−4.75), male (b=.06(.01), t=3.85) and African American (b=.11(.02), t=4.81) -- indicating that the relationship between school bonding and alcohol use was stronger (i.e., more negative) for older students, female students, and White students (compared to African American students). For school behavior, the age (b=−.06(.01), t=−7.14) and African American (b=.14(.02), t=6.64) interactions were statistically significant, indicating that the relationship between a student's positive behavior at school and alcohol use is more robust among older students and White students (compared to African American students). Finally, three level 1 interactions for having friend’s with strong school bonds were significant -- age (b=−.04(.01), t=−4.07), male (b=.06(.01), t=4.84), and African American (b=.09(.02), t=4.22), indicating that the relationship between friend's school bonding and alcohol use was stronger (i.e., more negative) for older students, female students, and White students (compared to African American students).

Figure II.

Illustration of interaction effects

Notes: AA=African American

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that a young adolescents’ own level of adjustment to school is predictive of his/her involvement with alcohol. These results corroborate past findings demonstrating a strong negative relationship between school adjustment and drug use (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Henry & Slater, 2007; Maddox & Prinz, 2003; McBride, et al., 1995; Resnick, et al., 1997). Furthermore, this study demonstrates that schools do differ in the degree to which their students are adjusted to school. That is, in some schools students tend to be better adjusted than in others. This is consistent with Welsh and colleagues (Welsh, 2000; Welsh, et al., 1999) theory and work indicating that school climate captures a legitimate aspect of schools and that schools, like people, can vary substantially on this personality-like construct. Finally, this study corroborates Henry and Slater’s (2007) and Batistich and Hom's (1997) findings, demonstrating that a strong contextual effect of school adjustment on alcohol use and other problem behaviors also exists, that the school environment has an influence above and beyond what would be expected based on the correlation between a student’s own level of school adjustment and alcohol use. This is an important finding that illuminates the salience of both an adolescent’s own level of school adjustment and the normative environment with regard to school adjustment at the student’s school.

Most of the variance in alcohol use is related to differences between individuals and a relatively small proportion of the variance occurs across schools. Across individuals, school adjustment accounts for an important but relatively modest part of the variance in alcohol use; but there are many other personal characteristics that are involved in alcohol use and a considerable body of research has explored these individual risk and protective factors. School adjustment is only one of these factors, although obviously an important one. Moreover, this study indicates that the relationship between school adjustment and alcohol use is somewhat less robust for African-American students. There are other significant interactions (i.e., for age and gender), but Figure 2 shows that the African American interactions appears in all of the graphs and is quite large compared to the other interactions. The significant interaction effects could have meant that there were few or no effects for some groups and that the results were due to larger differences in one group. But Figure 2 shows that is not the case. There are negative linear relationships for all groups, including African-Americans, not just some of the students. The weaker correlations for African-American students may be related to their lower level of alcohol use. If alcohol use is generally less normative among African-American students, even among those who have lower levels of school adjustment, the correlations may be weaker – deviance related to poor school adjustment may be played out in other ways, not in alcohol use. Further research would be needed to understand this effect and its implications. Some caution should also be used in interpreting the practical significance of these interactions given the very large level 1 sample size in this study.

In contrast, while differences across schools account for a much smaller part of the overall variance in alcohol use, the general level of school adjustment of students within a school accounts for a much larger percent of the variance in alcohol use rates across schools. While there are obviously many other differences between schools that produce what is called “school climate,” the average level of school adjustment of the students in these schools is apparently quite important, at least in terms of problem behaviors like alcohol use. This study suggests that school adjustment may be a critically important aspect of the school context.

Limitations

This study makes a significant contribution over previous contextual effects studies in that in uses a very large sample of rural schools, employs statistical techniques for decomposing the within school and contextual effects that reduce potential biases, considers several aspects of school adjustment, and explores the interaction of context and individual and school characteristics.

However, while this paper offers several important insights, it is important to recognize its limitations. First, although this study used a large national sample of communities, it did not include metro communities since that was not the purpose of the original study; therefore, the results may not generalize to schools in large metro areas. Second, because this study made use of existing data, it is also limited in the quality of the school adjustment measures. For example, our study did not measure other components of school adjustment that have been examined in the literature, such as school isolation, academic grades, or attendance. The consistency of the results across the three measures that were used, however, suggests that the findings are likely to generalize to other aspects of school adjustment as well. The study is also limited to 8th grade students, where alcohol use is less likely to be considered a normative or expected behavior. Results may differ considerably among older students where alcohol use is much more frequent. This is an important topic for future work in this area. Finally, because the sample is cross-sectional in nature, we cannot directly infer causality.

Implications

This study, as well as several others, suggests that the social context of the school environment plays an important role in predicting adolescent’s behavior. This may have important implications for policy as concerted efforts to improve the school climate (i.e., the normative environment with regard to school bonding, bonding to pro-social peers and teachers, fondness for school, and engagement in positive school behavior) may have desirable effects on adolescent alcohol use and probably on other behavior problems.

Gottfredson’s (1986) work in this area indicates that school climate can be improved and that it can have an important effect on student behaviors (including favorable effects on drug use). However, more work is needed to understand how school climate can best be improved. Several studies have laid the foundational work for such research, providing insight into the types of factors that influence the social context of schools. Rutter and colleagues (1979) suggest that schools demonstrate the best behavioral outcomes when students identify with the norms and goals of the school. This identification is most likely to occur when the school environment is pleasant, when there are positive bonds between students and teachers, when faculty and students regularly participate in activities together, when students frequently serve in leadership roles, and when students are high achievers. Similarly, Solomon and colleagues (1996) have shown that schools with a strong sense of community have teachers who are warm and supportive, accentuate pro-social values, promote cooperation, facilitate cooperative learning opportunities, provide opportunities for students to serve in leadership roles, and encourage classroom decision making about factors that affect the students’ environment.

In a recent issue of the Journal of School Health, a Wingspread Declaration on School Connections was published ([Anon], 2004). The declaration indicates that more work is needed in several critical areas, including the development of effective initiatives to promote school bonding among disenfranchised students, careful analysis of both the costs and effectiveness of different programs for promoting school bonding (including evaluation of new and existing programs that focus on staff/administrator training and target institutional structures), and assessment of the reciprocal relationship between students' level of school bonding and teacher morale, effectiveness, and turnover. Indeed, much more work is needed in this critical area of research.

The results of this study endorse the need to utilize contextual or ecological approaches to understand adolescent behavior. In this study, the importance of the school context in predicting adolescent alcohol use was examined, and we see that the contextual effect of school adjustment adds to the individual effect of a student's own adjustment to school. Although school differences account for a much smaller proportion of the variance associated with alcohol use and the school adjustment variables as compared to individual differences (as demonstrated by the small intraclass correlations), the potential for affecting adolescent behavior through school climate interventions may be great given the large number of adolescents that could be impacted by an improvement in their environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the staff of the Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research, Colorado State University, and the staff and students of the school districts under study, for making this research possible.

FUNDING

This research was supported by grants K01 DA017810 (awarded to Kimberly L. Henry) and R01 DA009349 (awarded to Ruth W. Edwards) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Students were given the Community Drug and Alcohol Survey (CDAS). The CDAS is a 99-item survey that asks a variety of questions related to substance use; school adjustment; relationships with family and peers; and other individual risk factors in substance use. The CDAS is a variation of the American Drug & Alcohol Survey (Oetting, Beauvais, & Edwards, 1984) and the Prevention Planning Survey (Oetting, Edwards, & Beauvais, 1996), which are the copyrighted property of Rocky Mountain Behavioral Science Institute, Inc. (“RMBSI”), a corporation located in Fort Collins, Colorado. This research project was granted permission to use and modify the survey through a special agreement between RMBSI and the Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research. Others wishing to use this survey or any other copyrighted instruments of RMBSI should contact RMBSI at 1-800-447-6354 or www.rmbsi.com.

Contributor Information

Kimberly L. Henry, Colorado State University, Department of Psychology, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1876, Phone: 970-491-5109, kim.henry@colostate.edu

Linda R. Stanley, Colorado State University, Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research

Ruth W. Edwards, Colorado State University, Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research

Lindsey C. Harkabus, Colorado State University, Department of Psychology

Laurie A. Chapin, Colorado State University, Department of Psychology

REFERENCES

- Anon. Wingspread declaration on school connections. Journal of School Health. 2004;74(7):233–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderman EM. School effects on psychological outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94(4):795–809. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Oxford, England: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Battistich V, Hom A. The relationship between students' sense of their school as a community and their involvement in problem behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(12):1997–2001. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Oesterle S, Fleming CB, Hawkins JD. The Importance of Bonding to School for Healthy Development: Findings from the Social Development Research Group. Journal of School Health. 2004;74(7):252–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and Crime: Current Theories. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Wiebe RP. The moderation of adolescent-to-peer similarity in tobacco and alcohol use by school levels of substance use. Child Development. 2003;74(1):279–291. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Early D, Frasier K, Belansky E, McCarthy K. The relation of connection, regulation, and support for autonomy to adolescents' functioning. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12(2):263–286. [Google Scholar]

- Eitle DJ, Eitle TM. School and county characteristics as predictors of school rates of drug, alcohol, and tobacco offenses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45(4):408–421. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DD, Huizinga DH, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Ageton SS, Canter RJ. Integrated theoretical perspective on delinquent-behavior. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1979;16(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Oxford ML, Harachi TW. A test of generalizability of the social development model across gender and income groups with longitudinal data from the elementary school developmental period. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2002;18(4):423–439. [Google Scholar]

- Frankowski B, Gereige R, Grant L, Hyman D, Magalnick H, Mears CJ, et al. The role of schools in combating illicit substance abuse. Pediatrics. 2007;120(6):1379–1384. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C, Espin OM. Identity Choices in Immigrant Adolescent Females. Adolescence. 1993;28(109):173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC. An Empirical-Test of School-Based Environmental and Individual Interventions to Reduce the Risk of Delinquent-Behavior. Criminology. 1986;24(4):705–731. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and Protective Factors for Alcohol and Other Drug Problems in Adolescence and Early Adulthood -Implications for Substance-Abuse Prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Guo J, Hill KG, Battin-Pearson S, Abbott RD. Long-term effects of the Seattle Social Development Intervention on school bonding trajectories. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5(4):225–236. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0504_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1985;6(2):73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Slater MD. The contextual effect of school attachment on young adolescents' alcohol use. Journal of School Health. 2007;77(2):67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of Delinquency. Oxford, England: U. California Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, McCarthy WJ. School-level contextual influences on smoking and drinking among Asian and Pacific Islander adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84(1):56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Children's social competence and social supports: Precursors of early school adjustement? In: Schneider G, Nadel AJ, Weissberg R, editors. Social competence in developmental perspective. Amsterdam: Kluwer; 1989. pp. 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Shifting ecologies during the 5 to 7 year period: Predicting children's adjustment during the transition to grade school. In: Sameroff A, Haith M, editors. The five to seven year shift. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1996. pp. 363–386. [Google Scholar]

- Libbey HP. Measuring Student Relationships to School: Attachment, Bonding, Connectedness, and Engagement. Journal of School Health. 2004;74(7):274–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke O, Marsh HW, Robitzch A, Trautwein U, Asparouhov T, Muthen B. The multilevel latent covariate model: A new, more reliable approach to group-level effects in contextual studies. Psychological Methods. 2008;13(3):203–229. doi: 10.1037/a0012869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox SJ, Prinz RJ. School bonding in children and adolescents: Conceptualization, assessment, and associated variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6(1):31–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1022214022478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes L, Lievens J. Can the school make a difference? A multilevel analysis of adolescent risk and health behaviour. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(3):517–529. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsueda RL. The Current State of Differential Association Theory. Crime & Delinquency. 1988;34(3):277–306. [Google Scholar]

- McBride CM, Curry SJ, Cheadle A, Anderman C, Wagner EH, Diehr P, et al. School-Level Application of a Social Bonding Model to Adolescent Risk-Taking Behavior. Journal of School Health. 1995;65(2):63–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1995.tb03347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LM, Muthen BO. Mplus User's Guide. 5th Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Peer cluster theory, socialization characteristics, and adolescent drug use: A path analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34(2):205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Orthogonal cultural identification theory: The cultural identification of minority adolescents. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1990–1991;25(5A & 6A):655–685. doi: 10.3109/10826089109077265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F, Edwards R. The American Drug and Alcohol Survey. Rocky Mountain Behavioral Science Institute, Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory: The etiology of drug use and deviance I. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33(4):995–1026. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Edwards R, Beauvais F. The Prevention Planning Survey. Rocky Mountain Behavioral Science Institute, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Anderson AL. Unstructured socializing and rates of delinquency. Criminology. 2004;42(3):519–549. [Google Scholar]

- Owens RG. Organizational behavior in education. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Perry KE, Weinstein RS. The social context of early schooling and children's school adjustment. Educational Psychologist. 1998;33(4):177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm - Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DL. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Maughan N, Mortimore P, Ouston J, Smith A. Fifteen thousand hours: Secondary schools and their effects on children. Wells: Open Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AM, Patrick H. The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents' motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal. 2001;38(2):437–460. [Google Scholar]

- Samdal O, Nutbeam D, Wold B, Kannas L. Achieving health and educational goals through schools - a study of the importance of the school climate and the students' satisfaction with school. Health Education Research. 1998;13(3):383–397. [Google Scholar]

- Shears J, Edwards RW, Stanley LR. School bonding and substance use in rural communities. Social Work Research. 2006;30(1):6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Crump AD. Association of parental involvement and social competence with school adjustment and engagement among sixth graders. Journal of School Health. 2003;73(3):121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Crump AD, Haynie DL, Saylor KE. Student-school bonding and adolescent problem behavior. Health Education Research. 1999;14(1):99–107. doi: 10.1093/her/14.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RL. Multilevel Analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D, Battistich V, Kim D-I, Watson M. Teacher practices associated with students' sense of the classroom as a community. Social Psychology of Education. 1996;1(3):235–267. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh WN. The effects of school climate on school disorder. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2000;567:88–107. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh WN, Greene JR, Jenkins PH. School disorder: The influence of individual, institutional, and community factors. Criminology. 1999;37(1):73–115. [Google Scholar]