Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

To describe the Heiney-Adams Recruitment Framework (H-ARF); to delineate a recruitment plan for a randomized, behavioral trial (RBT) based on H-ARF; and to provide evaluation data on its implementation.

Data Sources

All data for this investigation originated from a recruitment database created for an RBT designed to test the effectiveness of a therapeutic group convened via teleconference for African American women with breast cancer.

Data Synthesis

Major H-ARF concepts include social marketing and relationship building. The majority of social marketing strategies yielded 100% participant recruitment. Greater absolute numbers were recruited via Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waivers. Using H-ARF yielded a high recruitment rate (66%).

Conclusions

Application of H-ARF led to successful recruitment in an RBT. The findings highlight three areas that researchers should consider when devising recruitment plans: absolute numbers versus recruitment rate, cost, and efficiency with institutional review board–approved access to protected health information.

Implications for Nursing

H-ARF may be applied to any clinical or population-based research setting because it provides direction for researchers to develop a recruitment plan based on the target audience and cultural attributes that may hinder or help recruitment.

Recruitment, particularly minority accrual, is the Achilles heel of research (Mills et al., 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Accrual to national cooperative clinical trials is 5%–10% (Peppercorn, Weeks, Cook, & Joffe, 2004), and accrual to cancer control and behavior studies ranges from 14%–41% (Carlson, Speca, Patel, & Goodey, 2004; Keyzer et al., 2005; Linden et al., 2007; Margiti et al., 1999; Motzer, Moseley, & Lewis, 1997; Ott, Twiss, Waltman, Gross, & Lindsey, 2006; Richardson, Post-White, Singletary, & Justice, 1998) with few exceptions (Gil et al., 2006). African American participation in studies usually is 5% or less (Bakitas et al., 2009; Blacklock, Rhodes, Blanchard, & Gaul, 2010; Dirksen & Epstein, 2008; Powell et al., 2008). Although multiple and costly efforts have been instituted to increase accrual, researchers still are challenged to meet sample size requirements for their studies. Multiple barriers, such as patient, clinician, system, and trial design, have been cited as contributing to an inability to reach recruitment goals (Advani et al., 2003; BeLue, Taylor-Richardson, Lin, Rivera, & Grandison, 2006; Cudney, Craig, Nichols, & Weinert, 2004; Dancy, Wilbur, Talashek, Bonner, & Barnes-Boyd, 2004; Heiney et al., 2006; Lichtenberg, Brown, Jackson, & Washington, 2004; Linden et al., 2007; Sears et al., 2003). In addition, knowledge of the unethical research conducted during the U.S. Public Health Service Tuskegee Research Project syphilis study often is cited as a reason for non-participation by African Americans (Brandon, Isaac, & LaVeist, 2005; Corbie-Smith, Thomas, Williams, & Moody-Ayers, 1999; Freimuth et al., 2001; Katz et al., 2006, 2007; McCallum, Arekere, Green, Katz, & Rivers, 2006; Shavers, Lynch, & Burmeister, 2000, 2001, 2002; Wasserman, Flannery, & Clair, 2007; White, 2005). However, Heiney, Parrish, Hazlett, Wells, and Johnson (2008) found that 68% of African American participants felt that they received the same quality of health care as other ethnic groups and only 38% were aware of the Tuskegee Research Project. In addition, policies emanating from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) have hampered recruitment (Bowen et al., 2007; Rusnak, 2003).

Factors have been identified that influence minority participation in cancer research, particularly women and African American populations (Brown, Fouad, Basen-Engquist, & Tortolero-Luna, 2000; Outlaw, Bourjolly, & Barg, 2000; Shaya, Gbarayor, Yang, Agyeman-Duah, & Saunders, 2007). Most of the literature focuses on lessons learned in recruitment for specific cancer control studies, including randomized trials, rather than empirical data. A few studies tested specific interventions to delineate the most effective strategies (Ashing-Giwa, 1999; Hutchinson et al., 2003; Tworoger et al., 2002; Watkins-Bruner et al., 2004); however, not all were cancer studies (Areán, Alvidrez, Nery, Estes, & Linkins, 2003; Escobar-Chaves, Tortolero, Mâsse, Watson, & Fulton, 2002; Heinrichs, 2006; Lee, McGinnis, Sallis, Castro, & Chen, 1997; Levkoff & Sanchez, 2003; Lewis et al., 1998). Only one report provided an untested conceptual model along with suggestions for recruitment (Brown, Long, Gould, Weitz, & Milliken, 2000); therefore, researchers critically need a framework from which to develop and evaluate recruitment plans (Ashing-Giwa, 1999; Brown, Fouad, et al., 2000; Campbell et al., 2007; Levkoff & Sanchez, 2003). The purpose of this article is to (a) describe the Heiney-Adams Recruitment Framework (H-ARF); (b) delineate a recruitment plan for a randomized, behavioral clinical trial based on H-ARF; (c) provide evaluation data on its implementation; and (d) discuss results and recommendations for future research. This article provides data from the 88 patients recruited to a randomized, behavioral intervention trial for African American patients with breast cancer.

Heiney-Adams Recruitment Framework

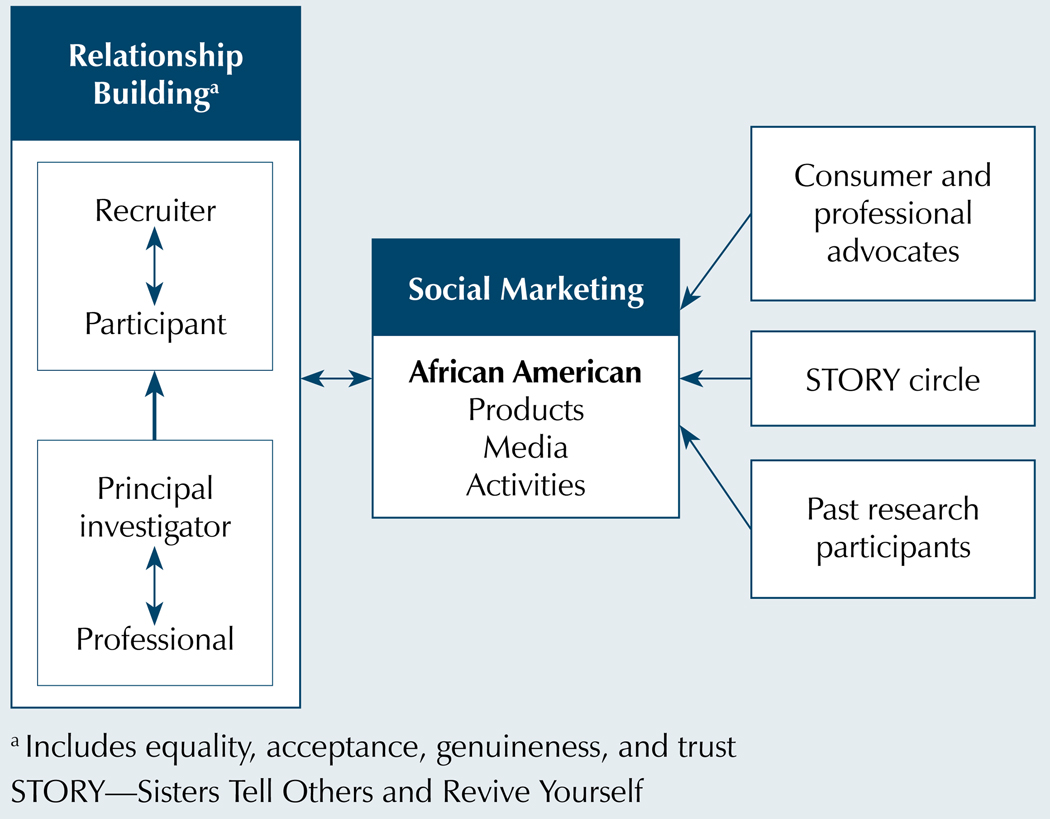

H-ARF (see Figure 1) evolved from the development of a recruitment framework for a cancer control study, an extensive review of the recruitment literature, the authors’ clinical and research experience, and examination of recruitment barriers (Heiney, Adams, Hebert, & Cunningham, 2005; Heiney et al., 2006, 2010; Heiney, Wells, & Johnson, 2008). H-ARF combines relationship building and social marketing. For clarity, the authors have separated the two approaches. However, overlap occurs, particularly as the project progresses. Relationship building and social marketing have reciprocal influences, strengthen and support each other, and are cumulative over time. These effects may confound evaluation of individual approaches.

Figure 1. Heiney-Adams Recruitment Model.

Note. Based on information from Airhihenbuwa, 2000; Brown, Fouad, et al., 2000; Cross & Cross, 1998; Gordon et al., 2006; Heiney et al., 2006; Manoff, 1985; Overholser, 2007.

Social Marketing

Social marketing in research is the use of traditional marketing strategies to influence attitudes and stimulate action in target groups (Hastings & McDermott, 2006; Lewis et al., 1998; Keyzer et al., 2005; Watkins-Bruner et al., 2005). Feedback from the community and attention to cultural issues are essential in designing social marketing strategies (Coleman et al., 1997). Social marketing includes development of the marketing message, identification of market segments, use of media, and production of materials (Manoff, 1985).

Relationship Building

Relationship building, based on person-centered counseling theory, is the creation of a trusting bond between the research staff and the patient and family (Corey, 2001; Cross & Cross, 1998; Overholser, 2007). This same bond is important in professional and principal investigator relationships. Neither are therapeutic relationships; instead, in both cases, the aim is to have a sense of ownership and affiliation with the research project and team.

The main premise of relationship building with patients is (a) the staff project an “I-thou” attitude, (b) staff are empathetic to the patient’s situation, and (c) staff are genuine in communications. The goal is to establish communication with the team that feels safe (i.e., the patient’s personhood is respected and his or her thoughts are important). Also, the interaction encourages questions and requests for more information. This approach avoids coercion and allows the patient to feel supported whether agreeing or declining to be enrolled (Overholser, 2007). At the same time, the likelihood of participation in the research study increases because the patient begins to make a personal connection with the research team. Relationship building has been established as critical in the African American population to increase trust (Ashing-Giwa, 1999; Dancy et al., 2004; Qualls, 2002; Watkins-Bruner et al., 2004).

The main premise of the professional and principal investigator relationship is that each has common goals which can be attained by working cooperatively. For example, a common goal might be to improve the health of the citizens of the community, particularly people experiencing health disparities. This can even be achieved in private practice settings in which the research team provides cutting-edge research that would be more appealing to a consumer. The focus is on mutual gain, not competition among healthcare providers. The hospital can include accrual to the study in accreditation reports, and the benefit to the principal investigator is to increase the pool of potential patients for recruitment.

Summary and Recruitment-Related Procedures

The major aim of this randomized trial was to test the effectiveness of a therapeutic group via teleconference called Sisters Tell Others and Revive Yourself (STORY) for African American women with breast cancer. The intervention group participated in eight weekly tele-conference sessions followed by two booster sessions that were two weeks apart. The control group underwent standard psychosocial care. The women completed three assessments (pretest, post-test I, and post-test II) in their homes or at a location of choice. Study participants received a thank-you gift at each assessment (such as a gift card from a local store or a small gift) and inexpensive thank-you gifts throughout the time they were enrolled. The authors recruited in replicate sets, or “waves” of subjects, with no more than 20 participants per wave so that the intervention group would have no more than 10 patients. Eligible participants were U.S. born, English speaking, African American women older than 21 who were diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma, including medullary, colloid, and tubular subtypes, whose treatment will be or has been excision biopsy or lumpectomy with adjunctive treatment (radiation and/or chemotherapy). Patients were at least 184 days from the month of diagnosis. Participants were excluded if they exhibited psychosis or major cognitive impairment, had a past diagnosis of breast cancer or past or current diagnosis of other types of cancer (except basal cell or squamous cell of skin), or were participating in another behavioral clinical trial. The authors enrolled patients from 2006–2008.

The study was approved by the authors’ institutional review board and the institutional review boards of community partners because recruitment efforts were statewide. The overall recruitment plan was included in the institutional review board protocol and detailed in the standard operating protocol manual. For this article, the authors submitted a protocol amendment to the institutional review board that detailed the plan for examining recruitment data. The amendment was approved.

Social Marketing Plan

Knowledge of the target audience and an understanding of its culture are essential to successful social marketing (Qualls, 2002). In laying the groundwork for patient recruitment, the authors consulted extensively with the African American community through patient and professional advisory committees. This core group chose the colors and logo design and endorsed the STORY acronym as the study name. In addition, the authors obtained feedback from a variety of African American consumer advocates and public relations professionals. The authors were very deliberative in building community and state support by involving hospital staff, politicians, church leaders, and others to help the authors tell the story of STORY. Also established was the STORY circle, an informal network of 98 volunteers, primarily African American women from health agencies, law firms, and churches who distributed STORY materials to churches and the community.

The authors deliberately chose words with STORY that reflected African American spirituality and story-telling, both strong features in the African American culture. These resonated with the African American community, helped increase public awareness of the project, and laid the groundwork for the recruiters. Also, the study’s marketing message addressed lack of trust and knowledge of the Tuskegee Research Project as possible factors that might decrease participation in the study; therefore, many recruitment pieces carried the tagline, “Our story is an open book.”

After the groundwork was completed, the authors focused on the three social marketing components: materials, media, and activities. Recruitment materials were developed and refined over time with new ones being created in response to patient and professional feedback. New material development was guided by the model. In all of the pieces, the authors used plain language and other low-literacy principles (such as color and white space) because the target audience has a known low literacy rate. Marketing pieces included (a) a poster for an acrylic stand with a pocket to hold self-addressed, postage-paid return cards; (b) a tri-fold brochure with return card; (c) a small and large flyer; and (d) a recruiter introduction flyer. Education pieces for the general public and professionals included a book mark and a fact sheet which evolved into a frequently asked questions format. The key recruitment piece, the tri-fold brochure, also included testimonials (originally from key community leaders and, later, from patients). The authors emphasized the personal availability of the staff using a special e-mail address, toll-free telephone number, and a dedicated voicemail to increase accessibility.

The authors worked with media outlets to place public service announcements and appeared on numerous radio talk shows and special television programs on breast cancer. Also, reporters for newspapers through-out the state were contacted in an effort to place human interest stories with quotations from patients involved in the project. Every effort was made to feature the community partner in the article. Five articles appeared in newspapers.

During the three years of the study, the authors participated in numerous activities to build community and demonstrate reciprocity, two strong cultural values that often were missing in past research with African American populations. These activities were designed to promote the project in the community and increase visibility, name recognition, and credibility. Activities included mailing brochures to 3,800 African American RNs in the state, making 6,386 contacts through booths or presentations at African American health fairs, placing more than 100 acrylic posters with reply cards in diagnostic and treatment facilities, and distributing information packets to Look Good … Feel Better® participants.

Relationship Building

Several activities were involved in establishing a trusting bond between each potential subject and the research team. These included, if appropriate, a cover letter from the principal investigator, the physician, or agency staff, and study brochures and flyers. In all interactions, recruiters approached the participants in a genuine and empathetic manner. The script for all telephone calls emphasized being patient-focused and sensitive to issues of time, fatigue, and family obligations. Recruiters inquired about the patients’ well-being prior to discussions about the project. They empathized with the patients’ experiences and listened in a respectful manner. Depending on the patient’s situation, the recruiter kept the initial call brief and obtained permission to call back later to discuss the study.

Sources of Data

Data used for this publication originated from self-referrals, community partner referrals (including physicians), and contact information through the HIPAA waiver mechanism (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002). HIPAA regulations provided researchers with access to patients’ protected health information through several mechanisms (Bowen et al., 2007). One mechanism, the waiver, allowed the researcher to obtain information about the patient without having a signed authorization from the patient. This waiver is granted through privacy board and/or institutional review board if provision of information involves no more than minimal risk to the privacy of individuals. With a HIPAA waiver, lists of all potentially eligible patients at an institution could be released to the investigative team for contact to assess interest in participation.

All data were entered into a recruitment database for tracking patients throughout the recruitment process. This procedure was described in the institutional review board application and study protocol and was approved prior to study initiation.

Recruitment Results

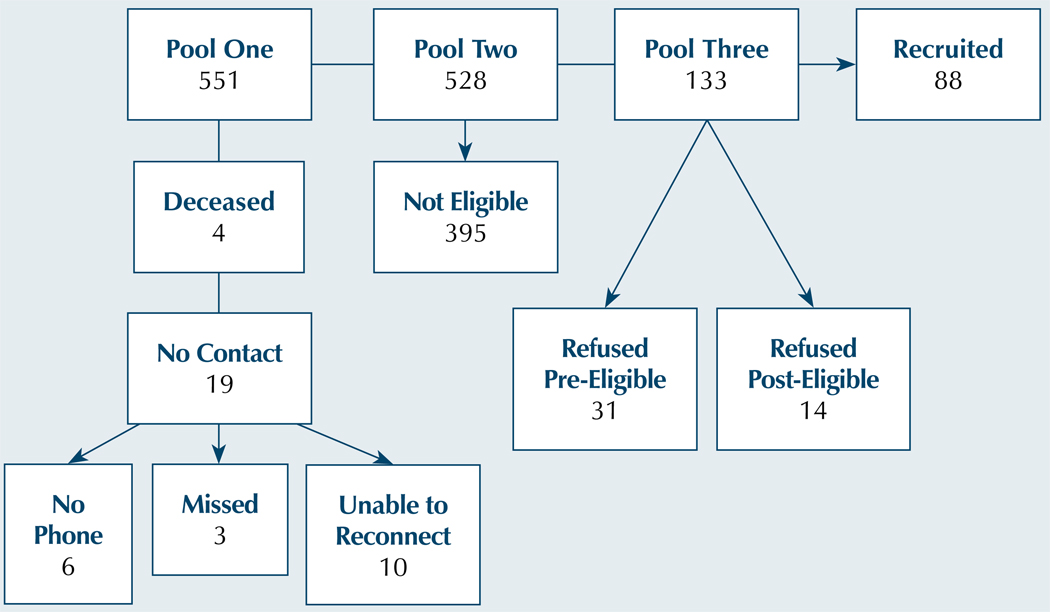

The overall pool consisted of 551 patients. Of the 551, 19 (3%) could not be contact and 4 (1%) were deceased. Of the 528 remaining patients, 395 (75%) were ineligible (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Reasons for Ineligibility

| Reason | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mastectomy | 148 | 37 |

| Diagnosis other than invasive ductal carcinoma | 115 | 29 |

| Diagnosed more than six months out | 46 | 12 |

| Not African American | 41 | 10 |

| No adjuvant treatment | 11 | 3 |

| Previous other type of cancer | 9 | 2 |

| Previous breast cancer | 8 | 2 |

| No surgical therapy | 6 | 2 |

| Major cognitive impairment | 5 | 1 |

| No cancer | 4 | 1 |

| Unable to assess | 2 | 1 |

N = 395

Of the remaining 133 patients, 31 (23%) refused prior to screening and 14 (11%) refused after screening. Reasons for declining to participate included 25 (56%) saying they were not interested, 12 (27%) saying they were too busy, 6 (13%) citing scheduling conflicts, and 2 (4%) saying they were too ill. Eighty-eight of the 133 patients were recruited, yielding a recruitment rate of 66%. The results are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Recruitment Flow Chart Demonstrating Patient Loss From Pool.

Results of Social Marketing

Data from self-referrals provide beginning evidence of the effectiveness of social marketing for recruitment. This information is detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Responses to Social Marketing

| Variable | Pool Onea |

No Contact |

Pool Twob |

Not Eligible |

Pool Threec |

Eligible Recruited |

%d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newspaper story | 3 | – | 3 | 3 | – | – | – |

| Other | 11 | – | 11 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Small poster with self-addressed, postage-paid return cards | 14 | 1 | 13 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Trifold brochure with tear-off return card | 11 | – | 11 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| Total | 39 | 1 | 38 | 34 | 4 | 4 | 100 |

Total contacts, including attempts

Initial pool minus no contact

Pool two minus not eligible

Recruited divided by pool three

Results of Relationship Building With Participants and Community Partners

Access to potential participants was specific to the partner site and institutional review board approval (see Table 3). At the three sites where the authors had access via HIPAA waiver to all potentially eligible patients (n = 426), the actual numbers recruited were much greater (ranging from 7–35) and the recruitment rate was reasonably high (50%–67%). Although the rates were better when patients were prescreened (67%–100%), the absolute number of patients accrued was higher with the waiver.

Table 3.

Recruitment by Referral Sources

| Referral Site | Pool Onea |

No Contact |

Pool Twob |

Not Eligible |

Pool Threec |

Refused Pre-Eligible |

Refused Post-Eligible |

Eligible Recruitedd |

%e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waiver | |||||||||

| Site 1 (private practice) | 180 | 7 | 173 | 121 | 52 | 10 | 7 | 35 | 67 |

| Site 2 (teaching hospital) | 197 | 5 | 192 | 145 | 47 | 13 | 4 | 30 | 64 |

| Site 3 (medical center) | 49 | 2 | 47 | 33 | 14 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 50 |

| Release of information with dedicated screener | |||||||||

| Site 4 (university hospital) | 84 | 4 | 80 | 68 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 67 | |

| Release with no dedicated screener | |||||||||

| Site 5 (medical center) | 3 | – | 3 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 1 | 100 |

| Site 6 (medical center) | 3 | – | 3 | – | 3 | – | – | 3 | 100 |

| Best Chance Network | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 517 | 18 | 499 | 370 | 129 | 28 | 17 | 84 | 65 |

Total contacts, including attempts

Pool one minus no contact

Pool two minus not eligible

Pool three minus refused

Recruited divided by pool three

Discussion

Application of H-ARF led to successful recruitment, as demonstrated by STORY. The findings highlight three areas that researchers should consider when devising recruitment plans: absolute numbers versus recruitment rate, cost, and efficiency with HIPAA waiver. However, the model remains a work in progress. Additional clarity is needed in the operational definitions, and outcome measures should be refined. The work is an early effort to develop the model and describes its use and evaluation in one study.

When considering findings in Tables 1–4 collectively, recruitment rates were the lowest for the institutions that granted a HIPAA waiver; however, the authors noted that they actually recruited the largest number of participants from these sources. This highlights the need for researchers to consider not only recruitment rates for their various recruitment plans, but also the absolute numbers each source is expected to yield. The researcher must weigh the benefits and drawbacks for the various plans and make an informed decision that will yield the most efficient and cost-effective method. Unfortunately, this is not always clear-cut because interplay often exists between the various methods. For example, social marketing techniques increase study visibility and name recognition, which yield lower absolute numbers but could ultimately impact recruitment rates for any location. In addition, the authors would have preferred a waiver at all sites, but unwillingness from physicians, institutions, or institutional review boards precluded using this approach at all locations.

Table 4.

Comparison of Sources for Recruited Patients

| Referral Source | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Waiver | 72 | 81 |

| Release of information with dedicated screener | 8 | 9 |

| Release with no dedicated screener | 4 | 5 |

| Social marketing | 4 | 5 |

N = 88

On initial evaluation, the least expensive approach with the greatest yield is the use of HIPAA waiver. However, in a research-naïve environment, the authors cannot comfortably recommend this as a sole approach and would expect recruitment efforts without social marketing to be abysmally low. The general population has been poorly educated about clinical trials and behavioral studies and is potentially more distrustful, particularly African Americans. In addition, the population’s known low literacy rate increased the importance of word-of-mouth marketing and presentations to increase knowledge about the project. Analysis of the impact of health fairs, posters, and other social marketing activities was beyond the scope of the current project. No data exist on motivation for social marketing responses or population baseline knowledge of research. Market researchers encountered similar issues when trying to determine the impact of an ad campaign. In seven waves, the authors obtained a total of eight patients through social marketing techniques. This represented 3% of the total planned sample (n = 240) for the study. Of the social marketing techniques, self-addressed return postcards attached to brochures or in a pocket with a poster yielded good results (25 of 39 responses). Printing of the posters and cost of the acrylic stands was less than $5 each, but the staff time and gas and mileage to place them across the state was expensive. If this method were used again, the authors would develop a coding system to determine exactly where a woman received the brochure or picked up a return card from the poster.

Print advertisements were very expensive. Ad placement in African American–focused publications yielded only one response, and that occurred a year after the ad was placed. In contrast, articles in local newspapers were free but involved staff time to meet with reporters, provide information, and provide consent for patients to be interviewed. However, the articles built good will with community partners. At a minimum, social marketing techniques for this kind of study should include an information brochure, a poster, and newspaper articles. The authors do not recommend paid media advertising; instead, placement of posters in locations where patients are likely to see them (e.g., cancer boutiques, treatment areas, diagnostic centers) was much more effective.

Results point to the need for additional relationship building with hospitals and physicians to obtain a waiver. Clear differences are present in recruitment rates when comparing HIPAA waiver to release of information or social marketing. This suggests that, when patients are approached by the treatment team, they may be too overwhelmed to agree to be in the study. However, if the communication to the patients occurs in the privacy of their homes and at their convenience, it may lead to higher recruitment rates and a sample that is more representative of the population of patients who would participate. This may be particularly true if patients need more information or time to decide about the study. In addition, the release of information may be a burden on staff and may lead to some selection bias about who is approached for the study.

In summary, H-ARF provides a testable model for researchers developing or implementing a recruitment plan. More research is needed on the social marketing component, particularly regarding cost. Additional ways to reduce barriers toward granting HIPAA waivers should be explored.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge their recruiters, Tamika Hunter, BS, MS, Rizanna Johnson, BA, MEd, Eleanor Jones, AD, Dana Mc-Cullough, BA, Carletta Wilson, AD, and Cassandra Wineglass, BA, MA, for their untiring efforts for STORY. The authors also would like to thank the following individuals and/or community partners for assistance with recruitment: Sandra Friddle, RN, at AnMed Health Cancer Center in Anderson; Myra Cochran, BS, at the Center for Cancer Prevention and Control at University of South Carolina in Columbia; Joyce Holley, RT, Sabrina Johnson, LPN, and Lorraine Harris, RN, at the Frances B. Ford Cancer Treatment Center, Georgetown Hospital System; Tricia Bentz, MHA, CCRP, Shanta Salzar, CCRP, and Marvella Ford, PhD, at Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina, in Charleston; Nannette Faile, RN, at the Lexington Medical Center; Chris Brunson, MD, at the Mabry Cancer Center Regional Medical Center in Orangeburg; Judy Bibbo, RN, Maureen Byrd, RN, and Linda Gremillion, MBA, at McLeod Regional Medical Center in Florence; and William Butler, MD, at South Carolina Oncology Associates in Columbia, all in South Carolina.

Funding for this research was provided by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA107305). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Heiney can be reached at heineys@mailbox.sc.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org.

Footnotes

This material is protected by U.S. copyright law. To purchase quantity reprints, reprints@ons.org. For permission to reproduce multiple copies, pubpermissions@ons.org.

References

- Advani AS, Atkeson B, Brown CL, Peterson BL, Fish L, Johnson JL, Gautier M. Barriers to the participation of African-American patients with cancer in clinical trials: A pilot study. Cancer. 2003;97:1499–1506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11213. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Kuymanyika SK, TenHave TR, Morssink CB. Cultural identify and health lifestyles among African Americans: A new direction for health intervention research? Ethnic Disparities. 2000;10:148–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areán PA, Alvidrez J, Nery R, Estes C, Linkins K. Recruitment and retention of older minorities in mental health services research. Gerontologist. 2003;43:36–44. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa K. The recruitment of breast cancer survivors into cancer control studies: A focus on African-American women. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1999;91:255–260. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2608496/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, Ahles TA. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. doi: 10.10001/jama2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BeLue R, Taylor-Richardson KD, Lin J, Rivera AT, Grandison D. African Americans and participation in clinical trials: Differences in beliefs and attitudes by gender. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2006;27:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.08.001. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacklock R, Rhodes R, Blanchard C, Gaul C. Effects of exercise intensity and self-efficacy on state anxiety with breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010;37:206–212. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.206-212. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.206-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Fann JR, Andersen MR, Rhew IC, Gralow JR, Lewis FM, Ankerst DP. Recruiting patients with breast cancer and their families to behavioral research in the post-HIPAA period. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34:1049–1054. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1049-1054. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1049-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon D, Isaac L, LaVeist T. The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: Is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97:951–956. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2569322/?tool=pubmed. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Long H, Gould H, Weitz T, Milliken N. A conceptual model for the recruitment of diverse women into research studies. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine. 2000;9:625–632. doi: 10.1089/15246090050118152. doi: 10.1089/15246090050118152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Fouad MN, Basen-Engquist K, Tortolero-Luna G. Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10(8) Suppl:S13–S21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00197-6. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(00)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Snowdon C, Francis D, Elbourne D, McDonald AM, Knight R STEPS Group. Recruitment to randomised trials: Strategies for trial enrollment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technology Assessment. 2007;11(48):iii. doi: 10.3310/hta11480. ix-105. Retrieved from http://www.hta.ac.uk/execsumm/summ1148.htm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson L, Speca M, Patel K, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress and levels of cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and melatonin in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:448–474. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00054-4. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA, Tyll L, LaCroix AZ, Allen C, Leveille SG, Wallace JI, Wagner EH. Recruiting African-American older adults for a community-based health promotion intervention: Which strategies are effective? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1997;13 Suppl. 2:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans towards participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14:537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey G. Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy. 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks-Cole/Wadsworth; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cross J, Cross P. Knowing yourself inside out. Berkeley, CA: Crystal Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cudney S, Craig C, Nichols E, Weinert C. Barriers to recruiting an adequate sample in rural nursing research. Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care. 2004;4(2):78–88. Retrieved from http://www.rno.org/journal/index.php/online-journal/article/viewFile/140/138. [Google Scholar]

- Dancy BL, Wilbur J, Talashek M, Bonner G, Barnes-Boyd C. Community-based research: Barriers to recruitment of African Americans. Nursing Outlook. 2004;52:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.04.012. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen SR, Epstein DR. Efficacy of insomnia intervention on fatigue, mood and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Advances in Nursing. 2008;61:664–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04560.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Chaves S, Tortolero S, Mâsse L, Watson K, Fulton J. Recruiting and retaining minority women: Findings from the Women on the Move study. Ethnicity and Disease. 2002;12:242–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth V, Quinn S, Thomas S, Cole G, Zook E, Duncan T. African Americans' views on research and the Tuskegee syphilis study. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00178-7. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil K, Mishel M, Belyea M, Germino B, Porter L, Clayton M. Benefits of the uncertainty management intervention for African American and white older breast cancer survivors: 20-month outcomes. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;13:286–294. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1304_3. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1304_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R, McDermott L, Stead M, Angus K. The effectiveness of social marketing interventions for health improvement: What’s the evidence? Public Health Nursing. 2006;120:1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings G, McDermott L. Putting social marketing into practice. BMJ. 2006;332:1210–1212. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7551.1210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7551.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiney S, Parrish RS, Hazlett LJ, Wells LM, Johnson H. Tuskegee revisited: Relationship of trust, knowledge, demographics and stress in African American women with breast cancer. Research and Practice in Columbia, SC: Poster presented at Nursing: Innovations in Leadership; 2008. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- Heiney SP, Adams S, Hebert J, Cunningham J. Subject recruitment for cancer control studies in an unfavorable environment. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32:162. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Heiney SP, Adams SA, Cunningham JE, McKenzie W, Harmon B, Hebert J, Modayil M. Subject recruitment for cancer control studies in an adverse environment. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29:291–301. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200607000-00007. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiney SP, Adams SA, Fisher-Drake B, Bryant LH, Bridges LG, Hebert JR. Subject recruitment for a prostate cancer behavioral trial. Clinical Trials Journal. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1740774510373491. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiney SP, Wells LM, Johnson H. Successful recruitment of African American breast cancer patients for telephone group intervention. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2008;35:494. [Abstract 2669] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs N. The effects of two different incentives on recruitment rates of families into a prevention program. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2006;27:345–365. doi: 10.1007/s10935-006-0038-8. doi: 10.1007/s10935-006-0038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson R, Gaynon P, Sather H, Bertolone S, Cooper H, Tannous R, Trigg ME. Intensification of therapy for children with lower-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Long-term follow-up of patients treated on Children’s Cancer Group Trial 1981. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:1790–1797. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz R, Green B, Kressin N, Claudio C, Wang M, Russell S. Willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical studies: Confirmatory findings from a follow-up study using the Tuskegee Legacy Project Questionnaire. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99:1052–1060. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz R, Kegeles S, Kressin N, Green B, Wang M, James S, Claudio C. The Tuskegee Legacy Project: Willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17:698–715. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0126. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyzer J, Melinkow J, Kuppermann M, Birch S, Kuenneth C, Nuovo J, Rooney M. Recruitment strategies for minority participation: Challenges and cost lessons from the POWER interview. Ethnicity and Disease. 2005;15:395–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RE, McGinnis KA, Sallis JF, Castro CM, Chen AH. Active vs. passive methods of recruiting ethnic minority women to a health promotion program. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;19:378–384. doi: 10.1007/BF02895157. doi: 10.1007/BF02895157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkoff S, Sanchez H. Lessons learned about minority recruitment and retention from the Centers on Minority Aging and Health Promotion. Gerontologist. 2003;43:18–26. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CE, George V, Fouad M, Porter V, Bowen D, Urban N. Recruitment strategies in the women’s health trial: Feasibility study in minority populations. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1998;19:461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00031-2. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(98)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Brown DR, Jackson JS, Washington O. Normative health research experiences among African American elders. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16(5) Suppl:78S–92S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304268150. doi: 10.1177/0898264304268150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden HM, Reisch LM, Hart AJ, Harrington MA, Nakano C, Jackson JC, Elmore JG. Attitudes toward participation in breast cancer randomized clinical trials in the African American community: A focus group study. Cancer Nursing. 2007;30:261–269. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000281732.02738.31. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000281732.02738.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoff RK. Social marketing. New York, NY: Praeger; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Margiti S, Sevick MA, Miller M, Albright C, Banton J, Callahan K, Ettinger W. Challenges faced in recruiting patients from primary care practices into a physical activity intervention trial. Activity Counseling Trial Research Group. Preventive Medicine. 1999;29:277–286. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0543. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum JM, Arekere DM, Green BL, Katz RV, Rivers BM. Awareness and knowledge of the U.S. Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee: Implications for biomedical research. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17:716–733. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0130. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, Griffith L, Wu P, Wilson K, Wright JR. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncology. 2006;7:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70576-9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer SA, Moseley JR, Lewis FM. Recruitment and retention of families in clinical trials with longitudinal designs. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1997;19:314–333. doi: 10.1177/019394599701900304. doi: 10.1177/019394599701900304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CD, Twiss JJ, Waltman NL, Gross GJ, Lindsey AM. Challenges of recruitment of breast cancer survivors to a randomized clinical trial for osteoporosis prevention. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29:21–33. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200601000-00004. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw FH, Bourjolly JN, Barg FK. A study of recruitment of black Americans into clinical trials through a cultural lens. Cancer Nursing. 2000;23:444–452. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200012000-00006. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overholser J. The central role of the therapeutic alliance: A simulated interview with Carl Rogers. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2007;37:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s10879-006-9038-5. [Google Scholar]

- Peppercorn JM, Weeks JC, Cook EF, Joffe S. Comparison of outcomes in cancer patients treated within and outside clinical trials: Conceptual framework and structured review. Lancet. 2004;363:263–270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15383-4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell CB, Kneier A, Chen L, Rubin M, Kronewetter C, Levine E. A randomized study of the effectiveness of a brief psychosocial intervention for women attending a gynecologic cancer clinic. Gynecologic Oncology. 2008;111:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.024. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualls CD. Recruitment of African American adults as research participants for a language in aging study: Example of a principled, creative, and culture-based approach. Journal of Allied Health. 2002;31:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MA, Post-White J, Singletary SE, Justice B. Recruitment for complementary/alternative medicine trials: Who participates after breast cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20:190–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02884960. doi: 10.1007/BF02884960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak E. The privacy rule’s effect on recruitment activities in clinical research. Research Practitioner. 2003;4:169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Sears SR, Stanton AL, Kwan L, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA. Recruitment and retention challenges in breast cancer survivorship research: Results from a multisite, randomized intervention trial in women with early stage breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2003;12:1087–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers V, Lynch C, Burmeister L. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12:248–256. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92:563–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Factors that influence African-Americans’ willingness to participate in medical research studies. Cancer. 2001;91(1) Suppl:233–236. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1+<233::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1+<233::AID-CNCR10>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaya FT, Gbarayor CM, Yang HK, Agyeman-Duah M, Saunders E. Perspective on African American participation in clinical trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2007;28:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.10.001. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tworoger SS, Yasui Y, Ulrich CM, Nakamura H, LaCroix K, Johnston R, McTiernan A. Mailing strategies and recruitment into an intervention trial of the exercise effect on breast cancer biomarkers. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2002;11:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Recruiting human subjects: Pressures in industry-sponsored clinical research. 2000 Retrieved from http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-97-00195.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Federal register: Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information: Final rule. Washington, DC: Author; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman J, Flannery MA, Clair JM. Raising the ivory tower: The production of knowledge and distrust of medicine among African Americans. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2007;33:177–180. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.016329. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.016329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins-Bruner D, Konski A, Feigenberg S, Dewberry-Moore N, Goplerud J. Benchmarking African American recruitment to cancer control trials with social marketing and direct response radio. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32:180. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins-Bruner D, Linton S, Konski A, Uzzo R, Greenberg R, Pollack A. Successful strategies for African American recruitment to prostate cancer research. International Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2004;1:295–306. [Google Scholar]

- White RM. Misinformation and misbeliefs in the Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis fuel mistrust in the healthcare system. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97:1566–1573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]