Abstract

Given that social influences are among the strongest predictors of adolescents’ drug use, this study examined the effect of social interaction on morphine-induced hyper-locomotion in both adolescent and adult mice. Three experimental groups of adolescent and adult male mice were examined: 1) morphine-treated mice (twice daily, 10–40 mg/kg, s.c.), 2) saline-injected mice housed together with the morphine-treated mice (‘saline cage-mates’), and 3) saline-injected mice housed physically and visually separated from the morphine-treated mice (‘saline alone’). Following the treatment period, mice were tested individually for their locomotor response to 10 mg/kg morphine (s.c.). Adolescent saline cage-mates, though administered morphine for the very first time, exhibited an enhanced hyper-locomotion response similar to the locomotor sensitization response exhibited by the morphine-treated mice. This was not observed in adults. In adults, there were no significant differences in morphine induced hyper-locomotion between saline alone and saline cage-mates. As expected, morphine-treated adults and adolescents both exhibited locomotor sensitization. These results demonstrate a vulnerability to social influences in adolescent mice which does not exist in adult mice.

Keywords: Morphine, Locomotion, Age-dependence, Peer-influences, Drug addiction, mouse

INTRODUCTION

Drug abuse is a major problem in the United States and around the world. It affects people from diverse socioeconomic strata and across all ages. While drug use among adolescents has remained relatively stable over the last few years, the current levels are still troubling with 14% of US 8th graders, 27% of 10th graders, and 37% of 12th graders using illicit drugs in the past year (Johnston et al., 2008). Drug use at any age, and especially during early adolescence, is problematic because it is a major predictor of later drug abuse and dependence (Chen et al., 2009, Grant and Dawson, 1998, Hawkins et al., 1997, Odgers et al., 2008). Additionally, an increased rate of comorbidity of anxiety and mood disorders was demonstrated when drug use began at a young age (Gfroerer et al., 2002, Caspi et al., 2005, Tucker et al., 2006, Mathers et al., 2006, Degenhardt et al., 2007).

There is considerable literature demonstrating differences between adolescents’ and adults’ response to different drugs of abuse. Specifically, for opioids, adolescent rodents are more sensitive to morphine-induced antinociception in the hot-plate procedure (Ingram et al., 2007), but less sensitive to the antinociceptive properties of morphine using the tail-flick test. No differences were found between adolescents and young adults in morphine-induced antinociception using the foot-shock technique (Nozaki et al., 1975). Adolescent rodents exhibit a more rapid onset of tolerance with repeated morphine administration (Ingram et al., 2007, Nozaki et al., 1975). Regarding morphine-induced hyperactivity, adolescent rats are more sensitive to acute morphine-induced locomotion (Spear et al., 1982, White et al., 2008). Additionally, morphine-treated adolescent rats exhibited a higher locomotor response to morphine during adulthood, thus suggesting that adolescents are more sensitive to locomotor sensitization (White et al., 2008). In reference to the rewarding properties of morphine, an earlier study showed a lack of morphine reward in adolescent mice (Bolanos et al., 1996), while two subsequent studies reported no differences in morphine reward between adolescents and adults (Campbell et al., 2000, Zheng et al., 2003). Additionally, adolescents and adults exhibit different affective responses in the forced swim test (FST) during opioid withdrawal (Hodgson et al., 2009).

There are many risk factors associated with adolescent drug use, and understanding the specific vulnerabilities to drug use in this age group is the first step in helping develop prevention strategies and more effective treatment programs for this at-risk group. Adolescence is a time of increased peer interaction. In fact, adolescents report peer pressure as a major factor in their decision-making process, and individuals between 10 and 15 years old are most prone to the influence of peers (Sumter et al., 2005). Peer influences are among the strongest predictors of adolescents’ drug use, and are commonly thought to be mediated by cultural influences on cognition and emotions. These peer influences include shaping adolescents’ attitudes toward drugs, initiating them into drugs, facilitating drug access, and providing models for drug-use behaviors. While most studies in humans have focused on cultural influences, some rodent studies suggest that there may be a non-cultural social effect from interaction with intoxicated peers (Hunt et al., 2001, Fernández-Vidal and Molina, 2004). Adolescent rats exposed to an ethanol intoxicated peer later showed a preference for the scent of ethanol. This effect was not observed after adolescent rats were exposed to the ethanol scent alone or after interaction with an intoxicated anaesthetized peer (Fernández-Vidal and Molina, 2004). Moreover, this social effect was also shown to increase drug intake; adolescent rats consumed more ethanol solution after exposure to an intoxicated peer (Hunt et al., 2001).

Increased self-administration following repeated drug use is believed to result from behavioral sensitization (Deroche-Gamonet et al., 2004, Horger et al., 1992, Piazza et al., 1989, Robinson and Berridge, 1993). Behavioral sensitization is the increase in the effects of drugs with repeated use (Robinson and Berridge, 1993). Behavioral sensitization in rodents also manifests as increased drug-induced hyperlocomotion following repeated drug administration (Robinson and Berridge, 1993, Wise and Bozarth, 1987). Additionally, cross-sensitization has been observed between different drugs of abuse (Shippenberg et al., 1998), between stress and drugs of abuse (Frances et al., 2000, Kostowski et al., 1977, Piazza et al., 1990, Rosario et al., 2002), and between palatable food and drugs of abuse (Avena and Hoebel, 2003, Gosnell, 2005).

This study examined the effect of social interactions on morphine-induced hyperlocomotion in both adolescent and adult mice. For each of these age groups, we tested two groups of drug-naïve (saline-injected) mice. One group of drug-naïve mice, which we call ‘saline cage-mates’, was housed together with mice receiving morphine. The other group of drug-naïve mice, which we refer to as ‘saline alone’, was physically and visually isolated from the mice receiving morphine. The mice were subsequently tested individually for their locomotor response to morphine.

METHODS

Subjects

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult and adolescent male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Lab (Houston, TX) and housed 4 per cage, with food and water freely available, in a temperature-controlled (21 ± 2 °C) vivarium with a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle (light on at 07:00). All mice were housed as cage-mates from the day of weaning (PND 21) in Harlan facilities, shipped as cage-mates, and remained cage-mates after arriving at our facility and for the entire experiment. Adolescent mice (Spear, 2000) were purchased at postnatal day 22 (PND 22), acclimated to the vivarium until PND 28, injected during PND 28–33, and behavioral testing was performed on PND 42. Adult mice were purchased at 4–5 weeks old (about PND 30), injected during PND 63–68, and tested at PND 77.

According to several studies, one week (and probably 3–4 days) is enough time for recovery from stress after shipping. For example, in one study (Landi et al., 1982) corticosterone (a marker for stress) returned to baseline levels within 48 hours of arrival. In a similar study, corticosterone and natural killer cells (the immune reaction to stress) returned to normal levels within 24 hours of shipping (Aguila et al., 1988). Additionally, rearing, climbing, grooming and feeding became stable from the second day after moving the mice to a new environment (Tuli et al., 1995). In our study, the mice were purchased from a local vendor and thus had a relatively short travel time as compared to those studies. They arrived at PND 22 and were given 6 days to recover prior to starting the morphine injections. By the time of their locomotion test they had already been in the vivarium for 20 days. Nonetheless, upon starting to work with adolescents, we were concerned with the possibility of stress. Thus we initially conducted a small preliminary experiment in which we compared responses for mice bred in-house (breeders were purchased from the same vendor) to mice that were shipped from that vendor at PND 22. We observed the same response in both groups and thus proceeded to use purchased mice for the rest of the study.

Saline and morphine treatment regimen

The different experimental groups are summarized in Table 1. The drug-naïve adult (PND 63, n=9–14) and adolescent (PND 28, n=23–26) mice were injected twice daily (9 a.m. and 5 p.m.) for 6 consecutive days with saline (s.c.). For each age, we had two groups of drug-naïve mice that received these 12 saline injections. In one group, the saline-injected mice were housed with mice receiving morphine (i.e. 2 mice receiving morphine and 2 mice receiving saline were housed in each cage). We refer to this group as ‘saline cage-mates’. The second group of saline-injected mice were housed physically and visually separated from the mice receiving morphine (i.e. all mice in the cage received saline). We refer to this group as ‘saline alone’.

Table 1.

Summary of the experimental groups

| Age group | Name | Exp days 1–6 | Exp days 7–14 | Exp day 15* | n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | Age | Treatment | Age | ||||

| Adolescents | Saline alone | Saline | PND 28–33 |

No treatment | Morphine (10 mg/kg) |

PND 42 |

26 |

| Saline cage-mates | Saline | 23 | |||||

| Morphine-treated | Morphine (10–40 mg/kg) |

23 | |||||

| Adult | Saline alone | Saline | PND 63–68 |

PND 77 |

14 | ||

| Saline cage-mates | Saline | 12 | |||||

| Morphine-treated | Morphine (10–40 mg/kg) |

9 | |||||

Locomotion recording

The mice receiving morphine (i.e. morphine-treated mice) were injected twice daily (9 a.m. and 5 p.m.) for 6 consecutive days with increasing morphine doses (10–40 mg/kg, s.c.) for a total of 12 injections. Specifically, on days 1 and 2, the mice were injected with 10 mg/kg morphine. On days 3 and 4, they were injected with 20 mg/kg morphine. On days 5 and 6, they were injected with 40 mg/kg morphine. This morphine regimen was selected based on both our previous studies (Eitan et al., 2003, Hodgson et al., 2009, Buckman et al., 2009) as well as those of other investigators (el-Kadi and Sharif, 1994, Spanagel et al., 1994, Matthes et al., 1996, Kest et al., 2001, Contet et al., 2008) who have demonstrated that such doses induce significant antinociceptive tolerance, locomotor sensitization, dependence and withdrawal.

Note that the sample size for adolescents is very large (n=23–26 per group). This is because we observed a result that differed significantly from adults; we therefore repeated the test multiple times in order to be certain that it was correct. Morphine sulfate was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Morphine hyperlocomotion

Nine days following the final treatment dose of morphine or saline (i.e. experimental day 15, Table 1), locomotion was recorded in the second part of the light phase, which is between 2 pm to 6 pm. Mice were habituated to the room for at least 30 minutes prior to testing and then placed separately (one mouse per apparatus) in an upright cylindrical container (261 mm in diameter and 355 mm high). The behavioral room contained 4 cylinders; thus 4 mice were individually recorded in the same room at the same time. Note that the mice were physically and visually separated during the locomotion test. However, to ensure that the response observed in not due to some other cues transferred between the mice, saline alone and saline cage-mate mice were both recorded at the same time and in the same behavioral room, and were placed in cylinders that were at identical distances from those of the morphine-treated mice. Baseline locomotion activity was recorded for 60 minutes by an overhead camera. Then all mice were injected with 10 mg/kg morphine and were recorded for another 60 minutes. The apparatus was cleaned thoroughly with water and completely dried between tests. Total distance traveled (locomotion) was scored using EthoVision 3.1 (Noldus Information Technology).

Data analyses

For each mouse, the morphine effect on locomotion was computed using the formula: [sum of the total distance traveled scores in the 60 minutes following morphine administration – sum of the baseline total distance traveled scores in the 60 minutes prior to morphine injection]. The overall design of the analyses was a factorial consisting of between-group factors of age (adolescent versus adult), and experimental group (saline cage-mates, saline alone, and morphine-treated). Separate analyses of variance were also computed for each age group for the total distance traveled scores (sum of baseline 60 minutes, and sum of post-morphine 60 minutes), and a within-group factor of time (1–120 minutes summed in 5 minute intervals). Additional post-hoc contrasts between each treatment group were computed using Bonferroni’s post-hoc procedure. Differences less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Adolescents

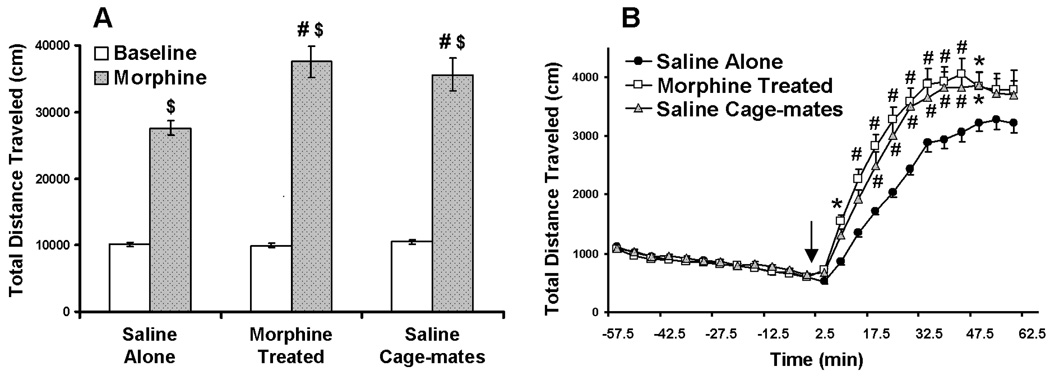

The results for the adolescents are presented in Fig 1. For the baseline and post-morphine total distance traveled scores (Fig 1A), two way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of pretreatment (F(2, 138)=7.11, p<0.001) and treatment (F(1, 138)=415, p<0.001), and a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F(2, 138)=7.03, p<0.001). Similarly, for the total distance traveled scores summed in 5 minute intervals over the 120 minute test (Fig 1B), two way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of pretreatment (F(2, 1656)=1.65, p<0.001) and time (F(23, 1656)=73.79, p<0.001), and a significant pretreatment × time interaction (F(46, 1656)=2.09, p<0.0001). Bonferroni’s post-hoc comparisons revealed no significant differences in baseline locomotor activity (the first 60 minutes) between the different treatment groups. In all the three experimental groups, locomotion increased following morphine administration (p<0.001 for each group’s baseline vs. post-morphine scores). As expected, the morphine-treated mice exhibited locomotion sensitization (morphine-treated vs. saline alone, p<0.001). The saline cage-mate mice exhibited a significantly higher hyperlocomotion response to morphine as compared to the saline-alone mice (saline cage-mates vs. saline alone, p<0.001). In fact, there was no significant difference in morphine-induced hyper-locomotion between the morphine-treated mice and the saline cage-mate mice.

Fig. 1. Morphine-induced hyper-locomotion in adolescent mice.

Mice were injected twice daily for 6 consecutive days with saline or morphine. Locomotion was recorded 9 days following the final injection of morphine or saline (i.e. experimental day 15, Table 1). Baseline locomotion activity was recorded for 60 minutes. All mice were then injected with 10 mg/kg morphine and recorded for another 60 minutes. (A) Total distance traveled (cm) in the 60 minutes prior to morphine administration (Baseline, White bars) and in the 60 minutes post morphine administration (Morphine, Gray bars). ($) indicates a significant difference from baseline (p<0.001); (#) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.001) (B) Total distance traveled (cm) during the entire 120 minute test, segmented into 5 minute intervals. Arrow indicates time of morphine administration. ● - saline alone mice; □ - morphine pretreated mice; and  - saline cage-mates. (*) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.05); (#) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.001). Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

- saline cage-mates. (*) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.05); (#) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.001). Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Adults

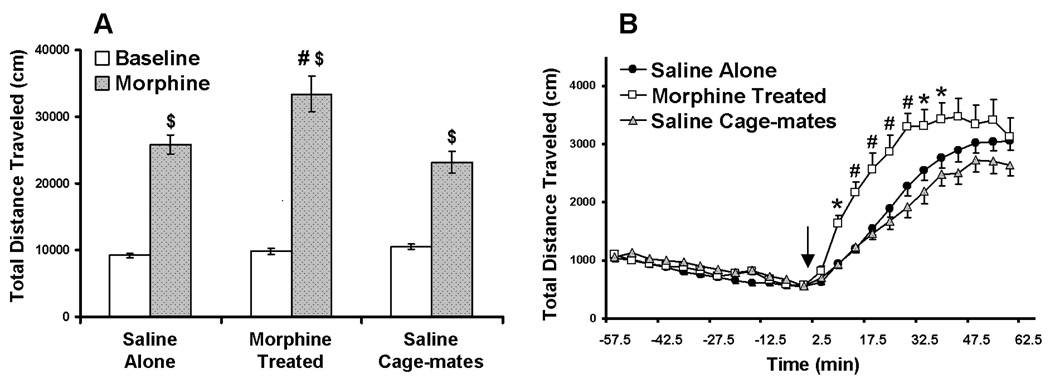

The results for the adults are presented in Fig 2. For the baseline and post-morphine total distance traveled scores (Fig 2A), two way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of pretreatment (F(2, 64)=7.86, p<0.001) and treatment (F(1, 64)=271.5, p<0.0001), and a significant pretreatment × treatment interaction (F(2, 64)=8.95, p<0.001). Similarly, for the total distance traveled scores summed in 5 minute intervals over the 120 minute test (Fig 2A), two way ANOVA revealed main effects of pretreatment group (F(2, 768)=2.79, p<0.001) and time (F(23, 768)=75.42, p<0.001), and a significant pretreatment × time interaction (F(46, 768)=4.41, p<0.001). Bonferroni’s post-hoc comparisons revealed no significant differences in baseline locomotor activity (the first 60 minutes) between the different treatment groups. In all three experimental groups, locomotion increased following morphine administration (p<0.001 for each group’s baseline vs. post-morphine scores). As expected, the morphine-treated mice exhibited locomotion sensitization (morphine-treated vs. saline alone, p<0.001). However, unlike adolescents, no significant differences were found between the adult saline cage-mate mice and the saline-alone mice.

Fig. 2. Morphine-induced hyper-locomotion in adult mice.

Mice were injected twice daily for 6 consecutive days with saline or morphine. Locomotion was recorded 9 days following the final injection of morphine or saline (i.e. experimental day 15, Table 1). Baseline locomotion activity was recorded for 60 minutes. All mice were then injected with 10 mg/kg morphine and recorded for another 60 minutes. (A) Total distance traveled (cm) in the 60 minutes prior to morphine administration (Baseline, White bars) and in the 60 minutes post-morphine administration (Morphine, Gray bars). ($) indicates a significant difference from baseline (p<0.001); (#) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.001) (B) Total distance traveled (cm) during the entire 120 minute test, segmented into 5 minute intervals. Arrow indicates time of morphine administration. ● - saline alone mice; □ - morphine pretreated mice; and  - saline cage-mate mice. (*) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.05); (#) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.001). Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

- saline cage-mate mice. (*) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.05); (#) indicates a significant difference from saline alone mice (p<0.001). Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Age-dependent differences

Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of age (F(1, 101)=7.78, p<0.001) and treatment group (F(2, 101)=12.72, p<0.001), and a significant age × treatment group interaction (F(2, 101)=5.63, p<0.05). Bonferroni’s post-hoc comparisons revealed a significant difference between the adolescent and adult saline cage-mates (p<0.001). No significant age-dependent differences were found between the saline-alone and morphine-treated mice.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates age-dependent vulnerabilities to social influences on morphine responsitivity. Adolescent saline-injected mice housed together with morphine-treated mice (i.e. saline cage-mates), when subsequently tested individually for morphine-induced hyperlocomotion, exhibited an enhanced hyperlocomotion response, as compared to mice that were housed separately from the morphine-treated mice (i.e. saline alone). This was not observed in adults – there was no significant difference in morphine induced hyper-locomotion between saline alone and saline cage-mate adult mice.

Adult and adolescent mice were examined in this study. The choice for the age of the adolescent mice was based on studies by Spear and colleagues (reviewed in (Spear, 2000)) which established three developmental stages for rodents from weaning to adulthood. Accordingly, in this study, mice were injected during what is considered the late phase of their prepubescent period (PND 28–33), and were tested during their mid-adolescence/periadolescent period (PND 42). We refer to this group as adolescents. Note that this study used mice of a post-natal age that was suggested to correspond to adolescence in humans (Spear, 2000). However, mice develop peri-natally differently than humans; thus this period might represent adolescence in humans on some levels but not for others. Therefore, the interpretation of the results, namely the extrapolation from a measure of rodent response to humans, should be performed with caution.

In this study, four mice were tested at a time, and they were separated physically and visually from each other during the test. Additionally, to control for the possibility that the response observed was not due to some other cues transferred between the mice, saline-alone and saline cage-mates mice were both recorded at the same time and in the same behavioral room, and were placed in apparatuses that were at identical distances from those of the morphine-treated mice. Nonetheless, we could not absolutely rule out the possibility that other cues (such as odor cues or ultrasonic vocalizations) transferred between the mice had some effect on their behaviors. It is possible that a cue presented by the morphine-treated mice would have a different effect on familiar mice (i.e. their cage-mates) and unfamiliar mice (i.e. the saline-alone group). It has been demonstrated that ‘pain empathy’ transferred through visual cues has a greater effect on the cage-mates compared to unfamiliar mice (Langford et al., 2006). Although odor or vocal cues transferred during the test might play some role, a more likely explanation is that the interactions between the morphine-treated mice and their cage-mates prior to the locomotion test played a significant role in the behavioral outcome observed.

One possible explanation for the enhanced hyperlocomotion response observed in adolescent saline cage-mates is that the interactions with the morphine-treated mice during intoxication and/or during the withdrawal period is stressful. Indeed, increased stress level is a known risk factor that correlates with substance abuse in both adolescents and adults (Cooper et al., 1992, Laurent et al., 1997, Sinha, 2001). Many theories stipulate that stress can potentiate drug abuse by increasing the propensity to initiate drug taking (Koob and LeMoal, 1997, Leventhal and Cleary, 1980, Shiffman, 1982, Sinha, 2001). For example, in humans, stress is correlated with higher levels of alcohol abuse (Cooper et al., 1992, Laurent et al., 1997). Similarly, stress can contribute to a relapse after a drug-free period (Childress et al., 1994, Cooney et al., 1997). Patients with severe withdrawal symptoms are more likely to relapse due to the increased stress experienced (Doherty et al., 1995). Likewise, in rodents, stress reinstates drug taking after a drug-free period (Ahmed and Koob, 1997, Buczek et al., 1999, Erb et al., 1996, Le et al., 1998, Shaham and Stewart, 1995, Stewart, 2000). Importantly, stress can also sensitize individuals to the effects of drugs. In rodents, drug sensitization is modeled as the increase in self-administration following repeated drug use (a manifestation of drug craving) or as increased drug-induced hyperlocomotion following repeated drug administration (Wise and Bozarth, 1987, Robinson and Berridge, 1993, Piazza et al., 1989, Horger et al., 1992, Deroche-Gamonet et al., 2004). Both acute and repeated stress increase levels of drug self-administration (Yajie et al., 2005, Shaham and Stewart, 1994, Piazza et al., 1990, Miczek and Mutschler, 1996, Goeders and Guerin, 1994). Likewise, acute and repeated stressors enhance drug-induced hyperlocomotion (Rosario et al., 2002, Piazza et al., 1990, Kostowski et al., 1977, Frances et al., 2000). The cross-sensitization between drugs and stress has been attributed to actions of the dopaminergic system (Saal et al., 2003, Pierce and Kalivas, 1997, Kalivas et al., 1998, Kalivas and Stewart, 1991). Exposure to stress and administration of drugs of abuse both lead to increased levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens (Kalivas and Stewart, 1991). Additionally, other neurotransmitters and/or hormones such as corticotrophin-releasing factor, endogenous opioids, or gonadal hormones, might also be involved.

Note that stress sensitizes both adults and adolescents to the effects of drugs of abuse. However, the effect observed in this study was age-dependent and an enhanced hyper-locomotion response was not observed in the adult cage-mates. This raises two possibilities - either stress does not play a significant role in the effect observed, or perhaps adolescents are more vulnerable to the effects of social stress on drug-induced behaviors. Indeed, human adolescents appear to experience more drastic mood changes and report more episodes of stress in their day-to-day lives (Spear, 2000, Arnett, 1999). While it is possible that adolescents do not experience more stress per se, they may perceive more situations as stressful (Spear, 2000). This increase in perceived stress during adolescence could help instigate drug use in this population. Similarly, in rodents, there is evidence that adolescents and adults might perceive different situations as stressful. Adolescent rodents housed in standard laboratory conditions (several animals per cage) have higher levels of corticosterone (a stress indicator) than adults (Laviola et al., 2002). However, crowded housing conditions did not further increase the corticosterone response in adolescent males. In adults, crowding is a known social stressor that results in an increased corticosterone response. Isolation (a social stressor in adults) resulted in a decrease of corticosterone basal levels in adolescents. Thus, it is possible that the results of this study represent yet another unexpected age-dependent difference in the effects of social stress.

An alternative explanation for the age-dependent differences in the enhanced hyper-locomotion response is that stress does play a significant role in the social effect observed, but morphine-treated adolescents and adults might display different aggressive behaviors which result in different effects on their age-matched cage-mates. An increase in aggressive behaviors is unlikely during morphine intoxication, since opioids have been demonstrated to decrease plasma testosterone levels in both adult humans (Abs et al., 2000, Rasheed and Tareen, 1995) and rodents (Budziszewska et al., 1999, Gabriel et al., 1986). Like adults, morphine was also demonstrated to decrease plasma testosterone levels in adolescent rats (Yilmaz et al., 1999, Cicero et al., 1989). Given that testosterone levels play a significant role in male aggressive behaviors, it is not surprising that morphine thus has anti-aggressive properties (Vivian and Miczek, 1993). However, in adults, morphine withdrawal increases aggressive behaviors (Sukhotina, 2001, Rodríguez-Arias et al., 1999, Felip et al., 2000). Note that although baseline aggression levels in rodents are significantly lower during early adolescence, their expression increases around puberty (~PND35) (Terranova et al., 1998). Adult rodent baseline aggressive behaviors are expected to be higher than adolescents, although this might not be the case during withdrawal. Indeed, during alcohol withdrawal, adolescent rodents exhibit increased play fighting, while adults exhibit social suppression and a decrease in play fighting (Varlinskaya, 2004). Moreover, adolescent and adult mice exhibit different mood responses in the FST paradigm during opioid withdrawal (Hodgson et al., 2009). Thus, it is possible that also during opioid withdrawal, adolescents and adults display different social interactions which result in age-dependent differences in the social effect on their cage-mates. Therefore, future experiments should examine aggressive behaviors in adolescents and adults during opioid withdrawal.

A third possible explanation for the age-dependent social effect is that olfactory cues are transmitted from the morphine-treated mice while intoxicated and/or during withdrawal. Indeed, olfactory cues transmitted during encounters with alcohol-intoxicated peers can affect alcohol preference and consumption in periadolescent mice (Fernández-Vidal and Molina, 2004, Hunt et al., 2001). Thus, perhaps pheromones secreted by the morphine-treated mice are affecting their saline-injected peers. Levels of many hormones do not peak until adulthood (Spear, 2000); hence there are baseline differences between these age groups. Hormone levels affect the amount of pheromones excreted in urine, which acts as a communication signal to conspecifics. Differential pheromone secretion due to altered hormone levels could potentially explain the age-specific effect. Adolescent mice could be secreting and sensing different pheromones or may have increased sensitivity to certain pheromones. However, little is known about the effects of pheromones on drug responsitivity and vulnerability, so any possible age-dependent differences on behavioral sensitization are currently unknown.

This study also raises some concerns regarding the common practice of housing drug-injected and saline-injected mice together. Although group housing might not be the common practice when conducting research on rats, a recent PubMed search revealed that this practice is common for mice. This study clearly demonstrates that social cues transferred from the morphine-treated mice have a pseudo-sensitizing effect on their adolescent drug-naïve cage-mates. Further experiments are still required to understand the generality of the phenomenon, but in any case, this study suggests that drug-treated adolescent mice should not be housed together with their saline controls. Moreover, given the social effect observed in one age group, perhaps caution should be taken with other age groups. Even though morphine-induced hyper-locomotion was not affected in the adult cage-mates, this study cautions to the possibility that a social effect could manifest for other age groups in other behavioral tests.

As expected, both adult and adolescent morphine-treated mice exhibited locomotor sensitization as compared to saline-injected mice housed separately (i.e. saline alone). Note that although it was suggested that adolescent rats might be more sensitive to morphine locomotor sensitization (White et al., 2008), our study did not find any significant differences in locomotor sensitization between the adult and adolescent morphine-treated groups. This lack of age-dependent differences in morphine sensitization in mice might represent species-dependent differences between mice and rats. Note that other species-dependent differences (Buckman et al., 2009, Hodgson et al., 2008, Morihisa and Glick, 1977) and strain-dependent differences (Szumlinski et al., 2005, Brodkin et al., 1999) in morphine-induced behaviors have been previously documented.

This study demonstrates age-dependent differences in the vulnerability to social influences on sensitivity to drugs of abuse. More specifically, social interactions with morphine-treated mice resulted in an enhanced hyper-locomotion response to morphine in drug-naïve adolescent mice. This did not occur in adults. Further studies are required to establish the duration of effect, the role of sex, possible social effects on other drug-induced behaviors (such as reward and self administration), and the generality of the phenomenon to drugs of abuse. Moreover, the molecular underpinnings of this social effect have yet to be determined. Drug use amongst teenagers is, and probably will always remain, a problem for societies around the world. Understanding the specific vulnerabilities to drug use in this age group is a first step in helping develop prevention strategies and more effective treatment programs for this at-risk group.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by NIH (DA022402); KWR is supported by NIH (P50DA05010). We also would like to thank Mr. Menachum M Slodowitz for his editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure/conflict of interest: The authors have no financial interests to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Abs R, Verhelst J, Maeyaert J, Van Buyten J-P, Opsomer F, Adriaensen H, et al. Endocrine Consequences of Long-Term Intrathecal Administration of Opioids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2215–2222. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.6.6615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguila HN, Pakes SP, Lai WC, Lu YS. The effect of transportation stress on splenic natural killer cell activity in C57BL/6J mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1988;38:148–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Cocaine- but not food-seeking behavior is reinstated by stress after extinction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132:289–295. doi: 10.1007/s002130050347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescent Storm and Stress, Reconsidered. Am Psychol. 1999;54:317–326. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.5.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM, Hoebel BG. Amphetamine-sensitized rats show sugar-induced hyperactivity (cross-sensitization) and sugar hyperphagia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74:635–639. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolanos CA, Garmsen GM, Clair MA, McDougall SA. Effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist U-50,488 on morphine-induced place preference conditioning in the developing rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;317:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00698-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodkin ES, Kosten TA, Haile CN, Heninger GR, Carlezon WA, Jatlow P, et al. Dark Agouti and Fischer 344 rats: differential behavioral responses to morphine and biochemical differences in the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 1999;88:1307–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman SG, Hodgson SR, Hofford RS, Eitan S. Increased elevated plus maze open-arm time in mice during spontaneous morphine withdrawal. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197:454–456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek Y, Le AD, Wang A, Stewart J, Shaham Y. Stress reinstates nicotine seeking but not sucrose solution seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;144:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s002130050992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budziszewska B, Leśkiewicz M, Jaworska-Feil L, Lasoń W. The effect of N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester on morphine-induced changes in the plasma corticosterone and testosterone levels in mice. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1999;107:75–79. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1212077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JO, Wood RD, Spear LP. Cocaine and morphine-induced place conditioning in adolescent and adult rats. Physiol Behav. 2000;68:487–493. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, McClay J, Murray R, Harrington H, et al. Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1117–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Early-onset drug use and risk for drug dependence problems. Addict Behav. 2009;34:319–322. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Ehrman R, McLellan AT, MacRae J, Natale M, O'Brien CP. Can induced moods trigger drug-related responses in opiate abuse patients? J Subst Abuse Treat. 1994;11:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, O'Connor L, Nock B, Adams ML, Miller BT, Bell RD, et al. Age-related differences in the sensitivity to opiate-induced perturbations in reproductive endocrinology in the developing and adult male rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248:256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contet C, Filliol D, Matifas A, Kieffer BL. Morphine-induced analgesic tolerance, locomotor sensitization and physical dependence do not require modification of micro opioid receptor, cdk5 and adenylate cyclase activity. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney N, Litt M, Morse P, Bauer L. Alcohol cue reactivity, negative mood reactivity and relapse in treated alcoholics. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:243–250. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and Validation of a Three-Dimensional Measure of Drinking Motives. Psychol Assess. 1992;4:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Moran P, Carlin JB, Patton GC. The predictors and consequences of adolescent amphetamine use: findings from the Victoria Adolescent Health Cohort Study. Addiction. 2007;102:1076–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche-Gamonet V, Belin D, Piazza PV. Evidence for Addiction-like Behavior in the Rat. Science. 2004;305:1014–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1099020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty K, Kinnunen T, Militello FS, Garvey AJ. Urges to smoke during the first month of abstinence: relationship to relapse and predictors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:171–178. doi: 10.1007/BF02246158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitan S, Bryant CD, Saliminejad N, Yang YC, Vojdani E, Keith D, Jr, et al. Brain Region-Specific Mechanisms for Acute Morphine-Induced Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Modulation and Distinct Patterns of Activation during Analgesic Tolerance and Locomotor Sensitization. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8360–8369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-23-08360.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Kadi AO, Sharif SI. The influence of various experimental conditions on the expression of naloxone-induced withdrawal symptoms in mice. Gen Pharmacol. 1994;25:1505–1510. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(94)90181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Shaham Y, Stewart J. Stress reinstates cocaine-seeking behavior after prolonged extinction and a drug-free period. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;128:408–412. doi: 10.1007/s002130050150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felip CM, Rodríguez-Arias M, Espejo EF, Miñarro J, Stinus L. Naloxone-induced opiate withdrawal produces long-lasting and context-independent changes in aggressive and social behaviors of postdependent male mice. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:424–430. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Vidal JM, Molina JC. Socially mediated alcohol preferences in adolescent rats following interactions with an intoxicated peer. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frances H, Graulet A-M, Debray M, Coudereau J-P, Gueris J, Bourre J-M. Morphine-induced sensitization of locomotor activity in mice: effect of social isolation on plasma corticosterone levels. Brain Res. 2000;860:136–140. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SM, Berglund LA, Kalra SP, Kalra PS, Simpkins JW. The influence of chronic morphine treatment on the negative feedback regulation of gonadotropin secretion by gonadal steroids. Endocrinology. 1986;119:2762–2767. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-6-2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer JC, Wu LT, Penne MA. Initiation of marijuana use: Trends, patterns, and implications. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; DHHS Publication No. SMA 02–3711, Analytic Series A–17. 2002

- Goeders NE, Guerin GF. Non-contingent electric footshock facilitates the acquisition of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;114:63–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02245445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosnell BA. Sucrose intake enhances behavioral sensitization produced by cocaine. Brain Res. 2005;1031:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: Results from the national longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic survey. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the Effects of Age of Alcohol Use Initiation and Psychosocial Risk Factors on Subsequent Alcohol Misuse. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:280–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson SR, Hofford RS, Norris CJ, Eitan S. Increased elevated plus maze open-arm time in mice during naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:805–811. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32831c3b57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson SR, Hofford RS, Wellman PJ, Eitan S. Different affective response to opioid withdrawal in adolescent and adult mice. Life Sci. 2009;84:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horger BA, Giles MK, Schenk S. Preexposure to amphetamine and nicotine predisposes rats to self-administer a low dose of cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:271–276. doi: 10.1007/BF02245147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PS, Holloway JL, Scordalakes EM. Social interaction with an intoxicated sibling can result in increased intake of ethanol by periadolescent rats. Dev Psychobiol. 2001;38:101–109. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(200103)38:2<101::aid-dev1002>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram SL, Fossum EN, Morgan MM. Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence for opioid tolerance in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:600–606. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Various stimulant drugs show continuing gradual declines among teens in 2008, most illicit drugs hold steady. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan News Service; 2008

- Kalivas PW, Stewart J. Dopamine transmission in the initiation and expression of drug- and stress-induced sensitization of motor activity. Brain Res Rev. 1991;16:223–244. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(91)90007-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Chris Pierce R, Cornish J, Sorg BA. A role for sensitization in craving and relapse in cocaine addiction. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:49–53. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kest B, Palmese CA, Hopkins E, Adler M, Juni A. Assessment of acute and chronic morphine dependence in male and female mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, LeMoal M. Drug Abuse: Hedonic Homeostatic Dysregulation. Science. 1997;278:52–58. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostowski W, Czlonkowski A, Rewerski W, Piechocki T. Morphine Action in Grouped and Isolated Rats and Mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1977;53:191–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00426491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi MS, Kreider JW, Lang CM, Bullock LP. Effects of shipping on the immune function in mice. Am J Vet Res. 1982;43:1654–1657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford DJ, Crager SE, Shehzad Z, Smith SB, Sotocinal SG, Levenstadt JS, et al. Social Modulation of Pain as Evidence for Empathy in Mice. Science. 2006;312:1967–1970. doi: 10.1126/science.1128322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, Callan MK, et al. Stress, alcohol-related expectancies and coping preferences: a replication with adolescents of the Cooper et al. (1992) model. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:644–651. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola G, Adriani W, Morley-Fletcher S, Terranova M. Peculiar response of adolescent mice to acute and chronic stress and to amphetamine: evidence of sex differences. Behav Brain Res. 2002;130:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Quan B, Juzytch W, Fletcher PJ, Joharchi N, Shaham Y. Reinstatement of alcohol-seeking by priming injections of alcohol and exposure to stress in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;135:169–174. doi: 10.1007/s002130050498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Cleary PD. The Smoking Problem: A Review of the Research and Theory in Behavioral Risk Modification. Psychol Bull. 1980;88:370–405. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers M, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, Williams J, Patton GC. Consequences of youth tobacco use: a review of prospective behavioural studies. Addiction. 2006;101:948–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes HW, Maldonado R, Simonin F, Valverde O, Slowe S, Kitchen I, et al. Loss of morphine-induced analgesia, reward effect and withdrawal symptoms in mice lacking the mu-opioid-receptor gene. Nature. 1996;383:819–823. doi: 10.1038/383819a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Mutschler NH. Activational effects of social stress on IV cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;128:256–264. doi: 10.1007/s002130050133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morihisa J, Glick S. Morphine-induced rotation (circling behavior) in rats and mice: species differences, persistence of withdrawal-induced rotation and antagonism by naloxone. Brain Res. 1977;123:180–187. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90654-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki M, Akera T, Lee CY, Brody TM. The effects of age on the development of tolerance to and physical dependence on morphine in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;192:506–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Caspi A, Nagin DS, Piquero AR, Slutske WS, Milne BJ, et al. Is It Important to Prevent Early Exposure to Drugs and Alcohol Among Adolescents? Psychol Sci. 2008;19:1037–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Simon H. Factors that predict individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Science. 1989;245:1511–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.2781295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, LeMoal M, Simon H. Stress- and pharmacologically-induced behavioral sensitization increases vulnerability to acquisition of amphetamine self-administration. Brain Res. 1990;514:22–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90431-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kalivas PW. A circuitry model of the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine-like psychostimulants. Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:192–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed A, Tareen IA. Effects of heroin on thyroid function, cortisol and testosterone level in addicts. Pol J Pharmacol. 1995;47:441–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Arias M, Pinazo J, Miñarro J, Stinus L. Effects of SCH 23390, Raclopride, and Haloperidol on Morphine Withdrawal-Induced Aggression in Male Mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario CNd, Pacchioni AM, Cancela LM. Influence of acute or repeated restraint stress on morphine-induced locomotion: involvement of dopamine, opioid and glutamate receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2002;134:229–238. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saal D, Dong Y, Bonci A, Malenka RC. Drugs of Abuse and Stress Trigger a Common Synaptic Adaptation in Dopamine Neurons. Neuron. 2003;37:577–582. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Stewart J. Exposure to mild stress enhances the reinforcing efficacy of intravenous heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;114:523–527. doi: 10.1007/BF02249346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Stewart J. Stress reinstates heroin-seeking in drug-free animals: An effect mimicking heroin, not withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:334–341. doi: 10.1007/BF02246300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Relapse Following Smoking Cessation: A Situational Analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50:71–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, LeFevour A, Thompson AC. Sensitization to the conditioned rewarding effects of morphine and cocaine: differential effects of the [kappa]-opioid receptor agonist U69593. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;345:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Almeida OF, Bartl C, Shippenberg TS. Endogenous kappa-opioid systems in opiate withdrawal: role in aversion and accompanying changes in mesolimbic dopamine release. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1994;115:121–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02244761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP, Horowitz GP, Lipovsky J. Altered behavioral responsivity to morphine during the periadolescent period in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1982;4:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(82)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. Pathways to relapse: the neurobiology of drug- and stress-induced relapse to drug-taking. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000;25:125–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhotina IA. Morphine withdrawal-facilitated aggression is attenuated by morphine-conditioned stimuli. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumter SR, Bokhorst CL, Steinberg L, Westenberg PM. The developmental pattern of resistance to peer influence in adolescence: Will the teenager ever be able to resist? J Adolesc. 2009;32:1009–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumlinski K, Lominac K, Frys K, Middaugh L. Genetic variation in heroin-induced changes in behaviour: effects of B6 strain dose on conditioned reward and locomotor sensitization in 129-B6 hybrid mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4:324–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terranova ML, Laviola G, de Acetis L, Alleva E. A description of the ontogeny of mouse agonistic behavior. J Comp Psychol. 1998;112:3–12. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.112.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Collins RL, Klein DJ. Does solitary substance use increase adolescents' risk for poor psychosocial and behavioral outcomes? A 9-year longitudinal study comparing solitary and social users. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:363–372. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuli JS, Smith JA, Morton DB. Stress measurements in mice after transportation. Lab Anim. 1995;29:132–138. doi: 10.1258/002367795780740249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Acute Ethanol Withdrawal (Hangover) and Social Behavior in Adolescent and Adult Male and Female Sprague-Dawley Rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:40–50. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000108655.51087.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivian JA, Miczek KA. Morphine attenuates ultrasonic vocalization during agonistic encounters in adult male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;111:367–375. doi: 10.1007/BF02244954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DA, Michaels CC, Holtzman SG. Periadolescent male but not female rats have higher motor activity in response to morphine than do adult rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Bozarth MA. A Psychomotor Stimulant Theory of Addiction. Psychol Rev. 1987;94:469–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yajie D, Lin K, Baoming L, Lan M. Enhanced cocaine self-administration in adult rats with adolescent isolation experience. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz B, Konar V, Kutlu S, Sandal S, Canpolat S, Gezen MR, et al. Influence of chronic morphine exposure on serum LH, FSH, testosterone levels, and body and testicular weights in the developing male rat. Arch Androl. 1999;43:189–196. doi: 10.1080/014850199262481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Ke X, Tan B, Luo X, Xu W, Yang X, et al. Susceptibility to morphine place conditioning: relationship with stress-induced locomotion and novelty-seeking behavior in juvenile and adult rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:929–935. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]