Abstract

1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25-(OH)2D3] inhibits proliferation of normal and malignant prostate epithelial cells at least in part through inhibition of G1 to S phase cell cycle progression. The mechanisms of the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 have yet to be fully elucidated but are known to require the vitamin D receptor. We previously developed a 1,25-(OH)2D3-resistant derivative of the human prostate cancer cell line, LNCaP, which retains active vitamin D receptors but is not growth inhibited by 1,25-(OH)2D3. Gene expression profiling revealed two novel 1,25-(OH)2D3-inducible genes, growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene gamma (GADD45γ) and mitogen induced gene 6 (MIG6), in LNCaP but not in 1,25-(OH)2D3-resistant cells. GADD45γ up-regulation was associated with growth inhibition by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in human prostate cancer cells. Ectopic expression of GADD45γ in either LNCaP or ALVA31 cells resulted in G1 accumulation and inhibition of proliferation equal to or greater than that caused by 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment. In contrast, ectopic expression of MIG6 had only minimal effects on cell cycle distribution and proliferation. Whereas GADD45γ has been shown to be induced by androgens in prostate cancer cells, up-regulation of GADD45γ by 1,25-(OH)2D3 was not dependent on androgen receptor signaling, further refuting a requirement for androgens/androgen receptor in vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition. These data introduce two novel 1,25-(OH)2D3-regulated genes and establish GADD45γ as a growth-inhibitory protein in prostate cancer. Furthermore, the induction of GADD45γ gene expression by 1,25-(OH)2D3 may mark therapeutic response in prostate cancer.

Induction of GADD45γ by vitamin D is sufficient for growth inhibition and marks sensitivity to vitamin D.

Epidemiological studies have shown an inverse correlation between sunlight exposure, a major source of vitamin D, and risk of prostate cancer mortality (1,2). In addition to a well-recognized role in maintaining calcium and phosphorous homeostasis, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25-(OH)2D3], the most active metabolite of vitamin D causes growth arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis in a variety of normal and malignant cell types (reviewed in Refs. 3,4,5,6). 1,25-(OH)2D3 physiological actions are mediated by binding to the vitamin D receptor (VDR), a ligand-activated transcription factor, which functions as a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor (4,7,8,9,10,11). VDR/retinoid X receptor heterodimers bind preferentially to cis-acting DNA sequences known as vitamin D response elements (VDREs) and modulate gene transcription (4,8). 1,25-(OH)2D3 also elicits rapid nongenomic effects; however, the role of these actions in cancer cell proliferation have not been established (12,13,14).

1,25-(OH)2D3 and its analogs inhibit tumor growth and angiogenesis of a variety of prostate cancer models tested in vivo and in cell culture (15,16,17,18,19). The antiproliferative effects mediated by 1,25-(OH)2D3 are dose dependent and increase with the duration of treatment (15,20). Growth inhibition by 1,25-(OH)2D3 requires VDR but VDR expression is not sufficient (16,18,21). In addition, 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment inhibited the formation of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (commonly considered the precursor to adenocarcinoma) in the Nkx3.1;Pten mutant mouse model of prostate cancer (17). Inhibition of cell cycle progression, particularly at the G1 to S transition, is a major mechanism for the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in prostate cancer cells (15,22,23). Although several G1 phase regulatory proteins have been implicated in 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated G1 accumulation the precise mechanism of action and factors involved are incompletely understood.

In this study, we sought to identify novel 1,25-(OH)2D3-regulated genes that are involved in growth inhibition of prostate cancer cells. We took advantage of isogenic cells that we previously derived by long-term culture of LNCaP cells in 1,25-(OH)2D3-containing media (24). The resulting VitD.R cells express functional VDR but are not growth inhibited by 1,25-(OH)2D3. We compared the gene expression patterns in the 1,25-(OH)2D3 growth-inhibited control LNCaP cells vs. resistant cells. Both growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene gamma (GADD45γ) and mitogen inducible gene 6 (MIG6) were up-regulated by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in control LNCaP but not VitD.R cells. GADD45γ is a DNA damage-inducible protein, whereas MIG6 is a negative-feedback inhibitor of ErbB receptor family members (25,26,27). These proteins have established antiproliferative effects in other cell types (25,26,28,29,30). GADD45γ was not up-regulated by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in the human prostate cancer cell line ALVA31, which expresses functional VDR but is not growth inhibited by 1,25-(OH)2D3 (21). Expression of GADD45γ resulted in significant G1 accumulation and inhibition of proliferation, whereas MIG6 expression had only minimal effects. Furthermore, induction of GADD45γ but not MIG6 by 1,25-(OH)2D3 marked 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated growth inhibition in prostate cancer cells. These data support a role for GADD45γ in the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and as a determinant of sensitivity to 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated antiproliferative effects.

Materials and Methods

Materials

1,25-(OH)2D3 was purchased from BioMol Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA), and ethanol-based stock solutions were stored at −20 C. Cell culture media (RPMI 1640, Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium, DMEM glutamax, and DMEM-high glucose) were obtained from Mediatech (Herndon, VA), and fetal bovine serum was from Hyclone (Logan, UT). A CalPhos transfection kit was obtained from CLONTECH (Mountain View, CA). Trizol was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-Flag antibody and cycloheximide was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Antibiotic and antimycotic was obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Grand Island, NY).

Cell culture

The human prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), ALVA31 (obtained from Drs. Stephen Loop and Richard Ostensen, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tacoma, WA), PC3, LNCaP Con.R, and LNCaP VitD.R were passaged and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 g/ml streptomycin, and 100 g/ml l-glutamine. The human prostate cancer cell line LAPC4 (provided by Dr. Charles Sawyers, Memorial Sloan Kettering, New York, NY) was passaged and maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 g/ml streptomycin, 100 g/ml l-glutamine, and 10 nm dihydrotestosterone. The human prostate cancer cell line VCaP (provided by Dr. Kenneth Pienta, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. MI) was passaged and maintained in DMEM glutamax supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% volume antibiotic+antimycotic. All of the cultures were maintained at 37 C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Cell proliferation assays

LNCaP and ALVA31 cells (selected for the expression of indicated lentiviral constructs or uninfected) were plated at an initial density of 50,000 or 25,000 cells/well in a six-well plate. The following day, the cells were treated with ethanol vehicle or 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3. After the indicated treatment times, the cells were trypsinized and the viable cells (those that exclude trypan blue) were counted using a hemocytometer. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was collected using Trizol according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Five hundred nanograms of total RNA were used for reverse transcriptase using a cDNA archive kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). One hundred nanograms of cDNA were used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) of CYP24A1, GADD45γ, and MIG6 and 1 ng for 18S rRNA. Taqman probes were used to perform real-time PCR using ABI Prism 7700 (Applied Biosystems). The comparative threshold cycle method was used to determine the relative mRNA expression level.

Flow cytometry

LNCaP cells and ALVA31 cells (selected for expression of indicated constructs or uninfected) were treated with ethanol vehicle or 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 for 72 h. Cells were then trypsinized and collected. Cells (∼1 × 106) were fixed at 4 C in 70% ethanol. Cells were counterstained with 50 ng/ml propidium iodide and RNA digested with 1 mg/ml ribonuclease (Roche Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). To determine DNA content, propidium iodide-stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using the FACSCAN (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) at the Flow Cytometry Core Facility, University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. Analyses were done on 10,000 total gated cells.

Constructs and lentiviral production

GADD45γ cDNA was purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD). An androgen receptor short hairpin RNA was generously provided by Dr. Paul Rennie (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). MIG6 cDNA was generously provided by Dr. Dazhong Xu (Tufts-New England Medical Center, Boston, MA). Gene expression cDNAs encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP), GADD45γ, and MIG6 were cloned into pQCXIN vector from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ) by PCR and verified by sequencing. For viral production, GP2–293 cells at 60–80% confluency in 100-mm dishes were transfected with 7.5 μg VSV-G and 12.5 μg pQCXIN (containing appropriate cDNA) using CalPhos kit (CLONTECH). Forty-eight hours after transfection, media containing viral particles were collected and filtered through 0.45 μm cellulose acetate and stored at −80 C. For selection, cells were infected with appropriate constructs 24 h after seeding and cultured in 1 mg/ml G418 48 h after infection for 5–8 d.

Microarray analysis

Microarray analysis was performed using Affymetrix Genechip Exon 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA) on Con.R cells treated with 1,25-(OH)2D3 or ethyl alcohol (EtOH) vehicle for 24 h and VitD.R cells treated with 1,25-(OH)2D3 for 24 h. Two experimental replicates were run independently. The preparation of probes and the microarray were done per the standard Affymetrix protocol. The results were analyzed by ExACT software (Affymetrix). All genes showing a 2-fold difference in any of the possible three comparisons were reported.

Results

GADD45γ and MIG6, novel 1,25-(OH)2D3-regulated genes revealed by gene expression analysis of prostate cancer cells resistant and sensitive to growth inhibition by 1,25-(OH)2D3

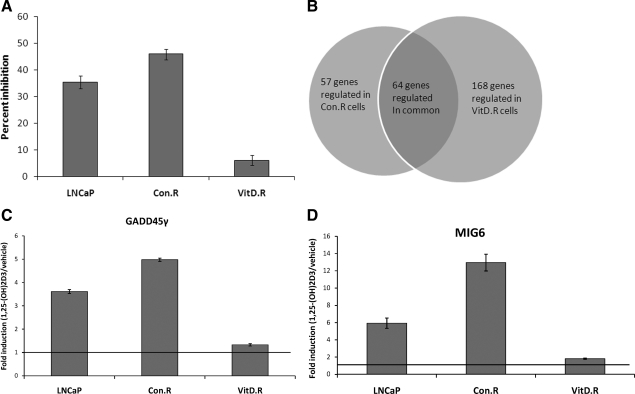

To identify targets of 1,25-(OH)2D3 that may play a role in the antiproliferative response of prostate cancer cells to 1,25-(OH)2D3, we conducted gene expression analyses of isogenic human prostate cancer cells that were sensitive (Con.R) or resistant (VitD.R) to growth inhibition by 1,25-(OH)2D3. These cells were developed by serial passage of LNCaP cells in 1,25-(OH)2D3 for more than 9 months; Con.R cells were passaged in parallel with vehicle treatment (24). We previously showed that VitD.R cells express comparable levels of ligand-inducible, transcriptionally active VDR as the control Con.R cells (24) (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). VitD.R cells are resistant to the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 (Fig. 1A) and maintain resistance 6 months after withdrawal of 1,25-(OH)2D3. VitD.R cells exhibit significant 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated inhibition of proliferation 7 months after withdrawal of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and exhibit growth inhibition comparable with parental LNCaP cells after 9 months (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction ofGADD45γ and MIG6 is associated with growth inhibition in LNCaP cells. A, Parental LNCaP and derivatives VitD.R and Con.R cells were treated with either 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 or EtOH vehicle for 72 h. Cell numbers were determined and the percentage inhibition of cell proliferation was calculated. Mean percent inhibition (±sem) of three experiments performed in triplicate is shown. B, Venn diagrams of microarray results. C and D, Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR using Taqman probes for GADD45γ (C) and MIG6 (D) and normalized to 18S (control) was performed 24 h after 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 or vehicle treatment. The mean induction of a total of three experiments performed in triplicate (±sem) is shown.

The goal of the present study was to identify genes whose expression was regulated by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in the sensitive Con.R cells but not in the cells resistant to growth inhibition by 1,25-(OH)2D3 (VitD.R) (Fig. 1B) through microarray analysis. To evaluate the strength of our microarray data, we identified ten 1,25-(OH)2D3 target genes from the literature. We chose genes that have reliably been shown to be regulated by 1,25-(OH)2D3. Of the 10 genes, six (TRPV6, CYP24A1, c-myc, IGFPB3, 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase, and TMPRSS2) are regulated in prostate cancer cells, whereas the remaining genes were identified as 1,25-(OH)2D3 targets in other cancer cell types (23,32,33,34,35,36,37,38). These 10 well-established, validated 1,25-(OH)2D3 target genes (nine are up-regulated and one is down-regulated) were regulated by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in both sensitive control cells (Con.R) and resistant VitD.R cells. Furthermore, six of the six genes examined were found to be appropriately regulated as determined by the reverse transcriptase qPCR. Thus, we conclude that these microarray data are robust.

GADD45γ and MIG6 were induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in the sensitive Con.R cells by 3.8- and 4.8-fold, respectively, but levels in the VitD.R cells were comparable to untreated Con.R cells. GADD45γ is a member of the growth arrest DNA damage inducible gene family, which includes α-, β-, and γ-proteins (25,39). These proteins are important inhibitors of cell growth and stimulators of apoptosis (28,29,39). MIG6 is an inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 (HER2/ErbB2) signaling by binding and blocking EGFR autophosphorylation, thereby abrogating downstream signaling (27,40). EGFR signals through proteins such as Ras, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt, and retinoblastoma (Rb) to promote cell cycle entry and progression. We chose these genes for further analysis because of their established roles in cell cycle regulation. Reverse transcriptase qPCR confirmed the findings from microarray that 1,25-(OH)2D3 induced the expression of GADD45γ and MIG6 gene expression in sensitive Con.R cells as well as in parental LNCaP, whereas minimal 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated up-regulation of these genes was seen in resistant VitD.R cells (Fig. 1, C and D).

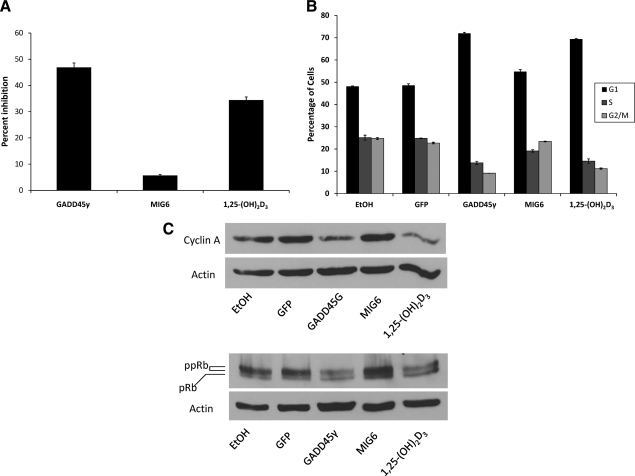

Ectopic expression of GADD45γ but not MIG6 was sufficient to inhibit proliferation and promote G1 accumulation similar to 1,25-(OH)2D3

GADD45γ causes either cell cycle inhibition or apoptosis, depending on cell type (25,28,41). MIG6 is a potent inhibitor of mitogenic stimulation (30). To determine whether these proteins inhibit proliferation of human prostate cancer cells similar to 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment, LNCaP cells were infected with retroviral constructs encoding either GADD45γ or MIG6 cDNAs (Fig. 2A). Whereas ectopic expression of GADD45γ was sufficient to cause substantial inhibition of proliferation [slightly greater than that seen with 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment], expression of MIG6 resulted in minimal inhibition of cell proliferation. Flow cytometry was conducted to determine whether, like 1,25-(OH)2D3, GADD45γ and MIG6 expression resulted in G1 accumulation (Fig. 2B). Whereas LNCaP cells expressing GADD45γ showed significant increases in cells in the G1 phase [similar to 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment], MIG6 expression resulted in only a small increase in G1 phase cells. Expression of GADD45γ but not MIG6 was also sufficient to decrease Rb hyperphosphorylation and to down-regulate cyclin A protein levels similar to 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that GADD45γ plays a significant role in the cell cycle inhibitory and antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3.

Figure 2.

Ectopic expression of GADD45γ but not MIG6 causes growth inhibition and G1 accumulation of LNCaP cells. A and B, Proliferation and cell cycle distribution of LNCaP cells stably expressing GADD45γ or MIG6 was compared with that of GFP-expressing cells (as a control) and with LNCaP cells treated for 72 h with 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 vs. EtOH vehicle. The mean percent growth inhibition (±sem) of a total of three experiments performed in triplicate is shown in A. The results of flow cytometry for a representative experiment (of three) performed in triplicate are shown in B as a mean percentage of the cells in each phase of the cell cycle (±sem). C, LNCaP cells expressing GFP, GADD45γ, and MIG6 and untransfected LNCaP cells treated with 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 or ETOH vehicle were harvested 72 h after infection with lentiviral constructs. Rb (pRb), hyperphosphorylated Rb (ppRb), cyclin A, and actin were detected by Western blotting. The Western blots shown are representative of a total of three experiments.

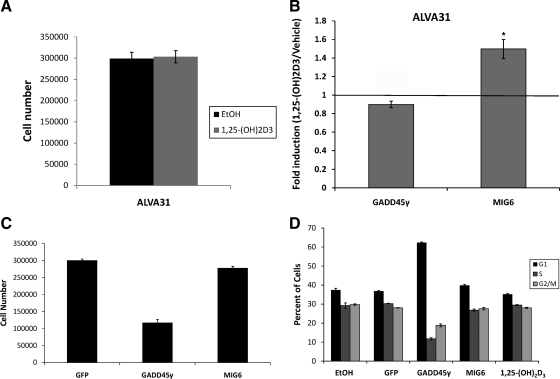

Lack of GADD45γ induction by 1,25-(OH)2D3 may underlie resistance to growth inhibition in ALVA31 cells

Whereas 1,25-(OH)2D3 inhibits the growth of the human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP by promoting G1 accumulation, the human prostate cancer cell line ALVA31 is insensitive to the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 despite the presence of higher levels of functional VDR (Fig. 3A and Ref. 21). The basis for resistance of ALVA 31 cells to 1,25-(OH)2D3--mediated growth inhibition is not known. Interestingly, 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment did not significantly induce GADD45γ gene expression compared with vehicle control in ALVA 31 cells (Fig. 3B). Whereas MIG6 mRNA was significantly induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3, the extent of this induction was substantially less than that seen in the 1,25-(OH)2D3-sensitive LNCaP and Con.R cells (Fig. 3B). We next examined the effects of ectopic expression of these proteins in ALVA 31 cells to determine whether either protein decreased cell proliferation. Expression of GADD45γ resulted in a 60% decrease in cell proliferation and induced substantial G1 accumulation, whereas forced expression of MIG6 resulted in only a slight decrease in proliferation and a small increase in G1 phase cells (Fig. 3, C and D). These results suggest that failure of 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ may underlie the resistance of ALVA31 cells to growth inhibition by 1,25-(OH)2D3.

Figure 3.

GADD45γ was not induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in resistant ALVA31 cells. A, Proliferation of ALVA31 cells treated with either 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 or EtOH vehicle for 72 h was evaluated. The data are representative of a total of three experiments done in triplicate (±sd). B, Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR using Taqman probes for GADD45γ and MIG6 and normalized to 18S (control) was performed 24 h after 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment. The mean fold induction (±sem) of a total of three experiments performed in triplicate is shown. C, A representative experiment (done in triplicate) of proliferation of ALVA31 cells stably expressing GADD45γ, MIG6, or GFP. D, ALVA31 cells stably expressing GADD45γ, MIG6, or GFP and untransfected ALVA31 cells treated with EtOH vehicle or 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 for 72 h were analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle (±sem) is shown for a representative experiment (performed in triplicate) of three total experiments. All statistical analyses were done using the Student’s t-test, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

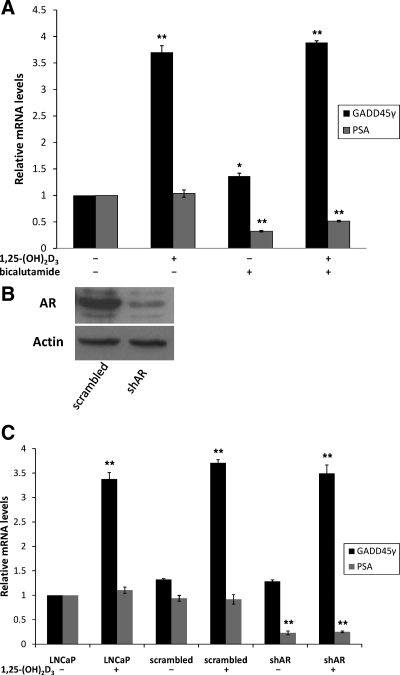

1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ does not require androgen receptor (AR) signaling

Androgen and AR are key regulators of prostate cancer cell proliferation (reviewed in Refs. 42,43,44). Recent reports have shown that GADD45γ is an androgen-regulated gene (45). This information along with reports linking AR activity with 1,25-(OH)2D3 antiproliferative effects led us to investigate the possible involvement of AR in GADD45γ induction by 1,25-(OH)2D3 (46). GADD45γ mRNA continued to be induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in the presence of bicalutamide (an AR antagonist) although, as expected, there was a significant decrease in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) mRNA levels, which are androgen inducible (Fig. 4A). To verify further that AR was not required for 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ, we knocked down AR using a short hairpin RNA retroviral construct and measured GADD45γ mRNA after 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment (Fig. 4, B and C). Induction of GADD45γ gene expression by 1,25-(OH)2D3 was similar in cells depleted of AR compared with controls. PSA mRNA levels were reduced as expected in the AR knockdown cells. These data demonstrate that 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ gene expression is not dependent on AR in prostate cancer cells.

Figure 4.

AR signaling is not involved in the up-regulation of GADD45γ by 1,25-(OH)2D3. A, Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR using Taqman probes for GADD45γ and PSA and normalized to 18S (control) was performed 24 h after 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3, 10 μm bicalutamide, or EtOH vehicle treatment. The results of a total of three experiments performed in triplicate are shown (±sem) (comparisons are to vehicle-treated controls). B, LNCaP cells infected with lentiviruses encoding either short hairpin AR or a scrambled control were harvested 72 h after infection and AR and actin were detected by Western blotting. The Western blot shown is representative of a total of three experiments. C, Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR using Taqman probes for GADD45γ and PSA normalized to 18S (control) was performed 24 h after 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment. The results of a total of three experiments performed in triplicate are shown (±sem) [comparisons are to vehicle-treated LNCaP cells (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01)].

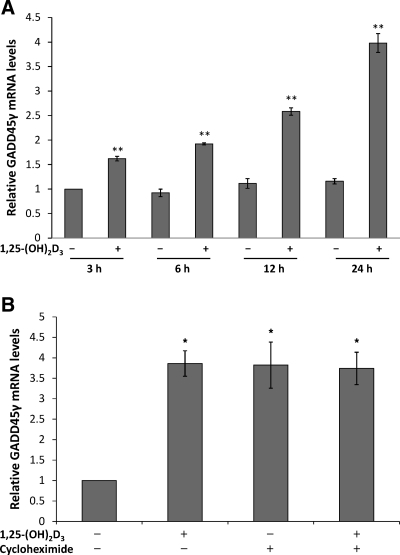

Regulation of GADD45γ by 1,25-(OH)2D3 requires new protein synthesis

To characterize 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ in greater detail, we conducted a time-course analysis in LNCaP cells. GADD45γ was significantly induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3 after 3 h and continued to increase up to and past 24 h of treatment (Fig. 5A and data not shown). These results are consistent with both direct and indirect VDR-mediated mechanisms. To determine whether ongoing protein synthesis was required, we used the inhibitor cycloheximide. LNCaP cells were pretreated with cycloheximide for 30 min and then treated with 1,25-(OH)2D3. Cycloheximide resulted in increased levels of GADD45γ mRNA as reported by others (45); however, addition of 1,25-(OH)2D3 had no further effect on GADD45γ mRNA levels compared with cycloheximide treatment alone (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that de novo protein synthesis is required for 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ gene expression. These findings are similar to those observed for several established 1,25-(OH)2D3 target genes including E-cadherin and CYP24A1 (Refs. 47 and 48 and data not shown).

Figure 5.

GADD45γ induction occurs in as little as 3 h yet requires de novo protein synthesis. A, Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR using Taqman probes for GADD45γ and normalized to 18S (control) was performed 24 h after 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 or vehicle treatment of LNCaP cells. The results of a total of three experiments performed in triplicate is shown experiment (±sem). B, LNCaP cells were treated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide for 30 min and then treated with 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 for 24 h. Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR using Taqman probes for GADD45γ and normalized to 18S (control) was performed. The results of a total of three experiments performed in triplicate are shown (±sem) [comparisons are to vehicle-treated controls (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01)].

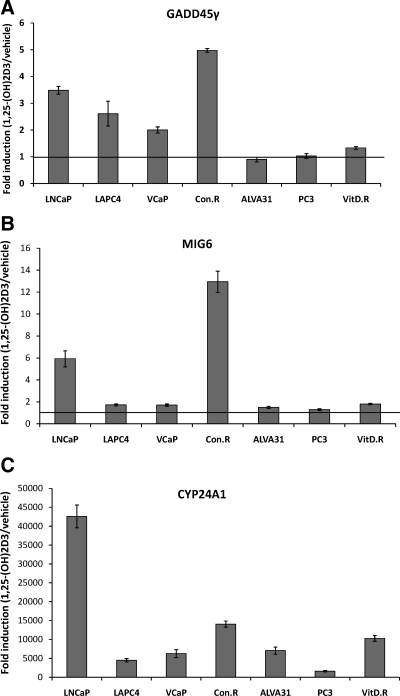

1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ is consistently associated with 1,25-(OH)2D3 antiproliferative effects

To address the relevance of GADD45γ and MIG6 induction in 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated antiproliferative effects, we tested a panel of human prostate cancer cell lines ranging from insensitive to highly sensitive to growth inhibition by 1,25-(OH)2D3 (Table 1). We examined the induction of GADD45γ mRNA after treatment with 1,25-(OH)2D3 and found that responses ranged from greater than 3-fold over vehicle control to no significant induction (Fig. 6A). All 1,25-(OH)2D3 growth-inhibited cells exhibited a 2-fold or greater induction of GADD45γ mRNA, whereas none of the 1,25-(OH)2D3 growth-resistant cells exhibited substantial induction (<1.4-fold). MIG6 mRNA was induced greater than 2-fold in two 1,25-(OH)2D3 growth-inhibited cell lines and less than 2-fold in all other sensitive and insensitive cell lines (Fig. 6B). All cell lines exhibited induction of the VDR target gene CYP24A1 to varying degrees (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these data suggest that GADD45γ, but not MIG6 induction, is associated with 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated growth inhibition and may be a determinant of the antiproliferative actions of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in prostate cancer cells.

Table 1.

1,25-(OH)2D3 effects on prostate cancer cell proliferation

| Cell type | Percent inhibition 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 72 h | sem |

|---|---|---|

| LNCaP | 35.48% | ±2.4 |

| LAPC4 | 38.73% | ±1.8 |

| V-CaPa | 30.97% | ±1.6 |

| Con.R | 45.94% | ±1.9 |

| ALVA31 | 2.47% | ±1.9 |

| PC-3 | 4.22% | ±0.8 |

| VitD.R | 6.14% | ±1.8 |

Cells were counted 72 h (

indicates 6 d treatment) after treatment with 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 or EtOH vehicle. Experiments were performed a total of three times in triplicate. The data represent mean inhibition of proliferation ± sem.

Figure 6.

GADD45γ induction by 1,25-(OH)2D3 predicts sensitivity to 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated growth inhibition. A–C, Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR using Taqman probes for GADD45γ (A), MIG6 (B), and CYP24A1 (C) and normalized to 18S (control) was performed 24 h after 50 nm 1,25-(OH)2D3 or vehicle treatment of the indicated cell lines. The results of a total of three experiments performed in triplicate are shown experiment (±sem).

Discussion

We performed gene expression profiling of isogenic 1,25-(OH)2D3 growth-inhibited and resistant LNCaP prostate cancer cells to identify new 1,25-(OH)2D3-regulated genes that may participate in 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated antiproliferative effects. The expression of both GADD45γ and MIG6 genes was induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in growth-inhibited LNCaP cells. In contrast, neither GADD45γ nor MIG6 was substantially induced in resistant LNCaP cells (VitD.R) or in ALVA31 cells, which express VDR but are not growth inhibited by 1,25-(OH)2D3. Ectopic expression of GADD45γ was sufficient to cause G1 accumulation and growth inhibition in both 1,25-(OH)2D3-sensitive LNCaP and ALVA31 cells. 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ occurred in 1,25-(OH)2D3 sensitive cell lines, whereas those resistant to the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 showed little to no induction of GADD45γ, suggesting that GADD45γ is sufficient for 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated antiproliferative effects. Furthermore, induction of GADD45γ by 1,25-(OH)2D3 served as a marker of 1,25-(OH)2D3 growth sensitivity in prostate cancer.

GADD45γ is a member of the growth arrest DNA damage-inducible gene family, which includes the α-, β-, and γ-proteins that have 55–58% amino acid identity and are generally nuclear proteins (25,39). These proteins are important inhibitors of cell growth and stimulators of apoptosis (28,29,39). GADD45γ mediates activation of the p38/c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway by binding to and inducing amino and carboxy terminal dissociation and dimerization-mediated autophosphorylation of MTK1, leading to growth arrest and apoptosis (49). GADD45γ also interacts with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), which plays a critical role in DNA replication and with CKI p21WAF1/CIP1, an inhibitor of G1 to S phase progression (50). The physiological significance of GADD45γ interactions with PCNA and p21WAF1/CIP1 have yet to be fully elucidated. There are a variety of proposed mechanisms by which GADD45γ induces G1 arrest, G2/M arrest, and apoptosis that depend on cell conditions and cell type (25,28,29,39,50). Interactions with MTK1, PCNA, and p21WAF1/CIP1 may play a role in GADD45γ-mediated G1 accumulation in prostate cancer cells because they all have been shown to affect cell cycle progression. GADD45γ is characterized as a potential tumor suppressor because its expression is silenced through CpG island DNA methylation in multiple tumors and ectopic expression of GADD45γ suppresses tumor cell growth and colony formation in a variety of cell lines (51,52,53). The role of CpG island methylation as a mechanism for resistance to 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ in VitD.R, ALVA31, and PC3 cells requires further investigation.

Studies in VDR knockout mice revealed that AR and VDR signaling pathways interact in the tumor microenvironment (54). Previous reports have also suggested that reduction in AR levels or treatment with AR antagonists decreases 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated antiproliferative effects in prostate cancer cells (46,55). A requirement for androgen/AR signaling in the antiproliferative actions of 1,25-(OH)2D3 could compromise the clinical utility of 1,25-(OH)2D3-based therapies for prostate cancer. The interpretation of data assessing the possible role of AR signaling in the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in prostate cancer is complicated by the dependence of LNCaP and certain other prostate cancer cell lines on AR and androgens for growth. Because AR antagonists or the reduction of AR levels cause significant growth inhibition of LNCaP cells, it may be difficult to observe further growth inhibition by 1,25-(OH)2D3. We previously showed that introduction of AR into ALVA31 cells did not result in growth inhibition of these cells (56). Because GADD45γ is induced by androgen in prostate cancer cells (45), we decided to investigate further the possible cross talk between AR and VDR pathways. Data presented here rule out a potential role for the AR in 1,25-(OH)2D3--mediated induction of GADD45γ and are consistent with a lack of AR involvement in 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated growth inhibition in LNCaP cells.

We found GADD45γ to be significantly induced in as little as 3 h after 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment, yet this induction continued to increase past the 24-h time point. The 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated induction of GADD45γ was blocked by the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, suggesting that GADD45γ induction may be a secondary event, although established 1,25-(OH)2D3 targets have been shown to require continued protein synthesis for maximal induction (33,47,48). The induction of GADD45γ by 1,25-(OH)2D3 may require short-lived coactivator proteins as is the case for maximal induction of CYP24A1 (33,57,58). Investigation into the promoter region of GADD45γ revealed four putative VDREs, although further investigation is necessary to confirm these sites as established VDREs (data not shown). The GADD45α gene is distinct from GADD45γ and is a 1,25-(OH)2D3 primary target in ovarian cancer cells. The regulation of this gene by 1,25-(OH)2D3 occurs via VDREs present in an exonic enhancer (59). However, we did not observe GADD45α induction by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in LNCaP cells (data not shown). The mechanism of 1,25-(OH)2D3 regulation of GADD45γ in LNCaP cells requires further investigation.

We show that the EGFR inhibitor MIG6 is a novel 1,25-(OH)2D3 inducible gene. MIG6 has tumor-suppressive actions in some cancers (26,60). Whereas MIG6 inhibits the proliferation of some cell types (26,30), ectopic expression of MIG6 in LNCaP and ALVA31 cells resulted in only a very slight inhibition of proliferation and minimal effects on G1 phase accumulation of cells. Cointroduction of MIG6 and GADD45γ did not result in a significantly greater inhibition compared with GADD45γ expression alone, ruling out the likelihood of cross-talk in these pathways (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that MIG6 is not a key growth inhibitory protein in prostate cancer cells. The reason for only minimal growth inhibition by MIG6 may lie in deregulation of EGFR downstream signaling that is a common feature in prostate cancer cells. The EGFR transmits mitogenic signaling by well-known pathways that involve RAS and AKT (61). Effectors of both of these proteins exhibit alterations in prostate cancer including hyperactivity of MAPKs and mutations in the AKT inhibitor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) deleted from chromosome 10, which are common in human prostate cancers and cell lines including LNCaP (62,63). Thus, expression of MIG6 may not counteract the hyperactive signaling downstream of EGFR.

There are a number of models that exhibit resistance to 1,25-(OH)2D3--mediated growth inhibition. The ALVA31 prostate cancer cell line is naturally insensitive to the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3. We previously showed that ALVA31 cells express approximately 2-fold higher levels of VDR than LNCaP and that the receptor is transcriptionally active (21). However, the molecular mechanism by which ALVA31 cells escape the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 had not been elucidated. Data presented here suggest that a plausible mechanism for 1,25-(OH)2D3 resistance of ALVA31 (and VitD.R) cells is an uncoupling between the VDR and specific targets that inhibit cell cycle progression. One such target appears to be the GADD45γ gene.

A variety of cell lines that have acquired resistance to the antiproliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 have been reported. We previously established LNCaP VitD.R cells, which retain functional VDR but are resistant to 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated antiproliferative effects (24). Using similar approaches, MCF-7 human breast cancer cells resistant to 1,25-(OH)2D3-induced apoptosis were developed. The mechanism of resistance in this model is through an uncoupling from a functional apoptotic pathway (64,65). In contrast, 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated growth inhibition of LNCaP cells occurs primarily through G1 to S inhibition (15,21,22,66), and VitD.R as well as ALVA31 cells are resistant to cell cycle inhibition after 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment. 1,25-(OH)2D3-resistant prostate cancer cells were developed from tumors of transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate mice that were chronically exposed to 1,25-(OH)2D3. These cells will also serve as a valuable tool for understanding the antiproliferative action of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and the mechanisms of acquired resistance in prostate cancer (67). Recently LNCaP cells resistant to the antiproliferative actions of 1,25-(OH)2D3 were reported. The basis for resistance in these cells was due to decreased nuclear factor-κB activity (68). Because nuclear factor-κB represses GADD45γ (69), such a mechanism is unlikely to explain our observation that 1,25-(OH)2D3 does not significantly increase GADD45γ in VitD.R cells.

Determining susceptibility and understanding the mechanism by which 1,25-(OH)2D3 exerts its antiproliferative effects in prostate cancer is essential for effective targeted therapy. We show that GADD45γ induction by 1,25-(OH)2D3 is an effective marker in all prostate cancer cell lines tested. This knowledge and a further understanding of the mechanism of action of vitamin D may contribute to the optimal use of vitamin D-based drugs when combined with chemotherapeutic agents such as docetaxel (31). The mechanism by which 1,25-(OH)2D3 enhances the actions of docetaxel may be linked to sensitization of neoplastic cells to genotoxic stresses and apoptosis. Interestingly, GADD45γ sensitizes cells to a variety of genotoxic stresses that induce apoptosis (39). The mechanism by which GADD45γ plays a role in 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated antiproliferative effects requires and warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Xu Dazhong (Tufts-New England Medical Center, Medford, MA), Stephen Loop and Richard Ostenson (Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tacoma, WA), Charles Sawyers (Memorial Sloan Kettering, New York, NY), and Kenneth Pienta (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) for generously providing reagents. We also thank Dr. Adena E. Rosenblatt for her advice and assistance, Ms. Stella Echandia and Dr. Lubov Nathanson (the Microarray and Gene Expression Core of John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics) and Mr. Jim Phillips (the Flow Cytometry Core Facility, University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center). We are also grateful to Dr. Wayne Balkan (Department of Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine) for help with the figures.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grant CA107705 from the National Institutes of Health (to K.L.B.). O.F. was supported by Training Grant T32-HL007188 from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online August 25, 2010

Abbreviations: AR, Androgen receptor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EtOH, ethyl alcohol; GADD, growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MIG6, mitogen induced gene 6; 1,25-(OH)2D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; qPCR, quantitative PCR; Rb, retinoblastoma; VDR, vitamin D receptor; VDRE, vitamin D response element.

References

- John EM, Schwartz GG, Koo J, Van Den Berg D, Ingles SA 2005 Sun exposure, vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms, and risk of advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Res 65:5470–5479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GG, Skinner HG 2007 Vitamin D status and cancer: new insights. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 10:6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan AV, Peehl DM, Feldman D 2003 The role of vitamin D in prostate cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res 164:205–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee P, Chatterjee M 2003 Antiproliferative role of vitamin D and its analogs—a brief overview. Mol Cell Biochem 253:247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LV, Weigel NL 2004 Vitamin D and prostate cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 229:277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS 2007 Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer 7:684–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman LP 1999 Transcriptional targets of the vitamin D3 receptor-mediating cell cycle arrest and differentiation. J Nutr 129:581S–586S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachez C, Freedman LP 2000 Mechanisms of gene regulation by vitamin D(3) receptor: a network of coactivator interactions. Gene 246:9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsony J, Prufer K 2002 Vitamin D receptor and retinoid X receptor interactions in motion. Vitam Horm 65:345–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J, Krishnan AV, Feldman D 2005 Molecular mechanisms mediating the anti-proliferative effects of Vitamin D in prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 97:31–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne J, Campbell MJ 2008 The vitamin D receptor in cancer. Proc Nutr Soc 67:115–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelli A, Massobrio M, Tesarik J 1998 Nongenomic effects of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3). Trends Endocrinol Metab 9:419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wali RK, Kong J, Sitrin MD, Bissonnette M, Li YC 2003 Vitamin D receptor is not required for the rapid actions of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 to increase intracellular calcium and activate protein kinase C in mouse osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem 88:794–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanello LP, Norman AW 2004 Rapid modulation of osteoblast ion channel responses by 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 requires the presence of a functional vitamin D nuclear receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:1589–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang SH, Burnstein KL 1998 Antiproliferative effect of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP involves reduction of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 activity and persistent G1 accumulation. Endocrinology 139:1197–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oades GM, Dredge K, Kirby RS, Colston KW 2002 Vitamin D receptor-dependent antitumour effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and two synthetic analogues in three in vivo models of prostate cancer. BJU Int 90:607–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banach-Petrosky W, Ouyang X, Gao H, Nader K, Ji Y, Suh N, DiPaola RS, Abate-Shen C 2006 Vitamin D inhibits the formation of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in Nkx3.1;Pten mutant mice. Clin Cancer Res 12:5895–5901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung I, Han G, Seshadri M, Gillard BM, Yu WD, Foster BA, Trump DL, Johnson CS 2009 Role of vitamin D receptor in the antiproliferative effects of calcitriol in tumor-derived endothelial cells and tumor angiogenesis in vivo. Cancer Res 69:967–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokeshwar BL, Schwartz GG, Selzer MG, Burnstein KL, Zhuang SH, Block NL, Binderup L 1999 Inhibition of prostate cancer metastasis in vivo: a comparison of 1,23-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) and EB1089. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8:241–248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowronski RJ, Peehl DM, Feldman D 1993 Vitamin D and prostate cancer: 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors and actions in human prostate cancer cell lines. Endocrinology 132:1952–1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang SH, Schwartz GG, Cameron D, Burnstein KL 1997 Vitamin D receptor content and transcriptional activity do not fully predict antiproliferative effects of vitamin D in human prostate cancer cell lines. Mol Cell Endocrinol 126:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ES, Burnstein KL 2003 Vitamin D inhibits G1 to S progression in LNCaP prostate cancer cells through p27Kip1 stabilization and Cdk2 mislocalization to the cytoplasm. J Biol Chem 278:46862–46868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohan JN, Weigel NL 2009 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces c-Myc expression, inhibiting proliferation and causing G1 accumulation in C4–2 prostate cancer cells. Endocrinology 150:2046–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores O, Wang Z, Knudsen KE, Burnstein KL 2010 Nuclear targeting of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 reveals essential roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 localization and cyclin E in vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition. Endocrinology 151:896–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa M, Saito H 1998 A family of stress-inducible GADD45-like proteins mediate activation of the stress-responsive MTK1/MEKK4 MAPKKK. Cell 95:521–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferby I, Reschke M, Kudlacek O, Knyazev P, Pantè G, Amann K, Sommergruber W, Kraut N, Ullrich A, Fässler R, Klein R 2006 Mig6 is a negative regulator of EGF receptor-mediated skin morphogenesis and tumor formation. Nat Med 12:568–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasi S, Baietti MF, Frosi Y, Alemà S, Segatto O 2007 The evolutionarily conserved EBR module of RALT/MIG6 mediates suppression of the EGFR catalytic activity. Oncogene 26:7833–7846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Richter G, Cereseto A, Beadling C, Smith KA 1999 Cytokine response gene 6 induces p21 and regulates both cell growth and arrest. Oncogene 18:6573–6582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Bae I, Krishnaraju K, Azam N, Fan W, Smith K, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA 1999 CR6: a third member in the MyD118 and Gadd45 gene family which functions in negative growth control. Oncogene 18:4899–4907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Makkinje A, Kyriakis JM 2005 Gene 33 is an endogenous inhibitor of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor signaling and mediates dexamethasone-induced suppression of EGF function. J Biol Chem 280:2924–2933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer TM, Ryan CW, Venner PM, Petrylak DP, Chatta GS, Ruether JD, Redfern CH, Fehrenbacher L, Saleh MN, Waterhouse DM, Carducci MA, Vicario D, Dreicer R, Higano CS, Ahmann FR, Chi KN, Henner WD, Arroyo A, Clow FW, ASCENT Investigators 2007 Double-blinded randomized study of high-dose calcitriol plus docetaxel compared with placebo plus docetaxel in androgen-independent prostate cancer: a report from the ASCENT Investigators. J Clin Oncol 25:669–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieben L, Benn BS, Ajibade D, Stockmans I, Moermans K, Hediger MA, Peng JB, Christakos S, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G 2010 Trpv6 mediates intestinal calcium absorption during calcium restriction and contributes to bone homeostasis. Bone 47:301–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zierold C, Mings JA, Prahl JM, Reinholz GG, DeLuca HF 2002 Protein synthesis is required for optimal induction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3)-24-hydroxylase, osteocalcin, and osteopontin mRNA by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3). Arch Biochem Biophys 404:18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Malloy PJ, Feldman D 2004 Identification of a functional vitamin D response element in the human insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 promoter. Mol Endocrinol 18:1109–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan AV, Shinghal R, Raghavachari N, Brooks JD, Peehl DM, Feldman D 2004 Analysis of vitamin D-regulated gene expression in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells using cDNA microarrays. Prostate 59:243–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akutsu N, Lin R, Bastien Y, Bestawros A, Enepekides DJ, Black MJ, White JH 2001 Regulation of gene Expression by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Its analog EB1089 under growth-inhibitory conditions in squamous carcinoma Cells. Mol Endocrinol 15:1127–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington MN, Weigel NL 2010 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits growth of VCaP prostate cancer cells despite inducing the growth-promoting TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion. Endocrinology 151:1409–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeenrezakhanlou A, Nandan D, Reiner NE 2008 Identification of a calcitriol-regulated Sp-1 site in the promoter of human CD14 using a combined Western blotting electrophoresis mobility shift assay (WEMSA). Biol Proced Online 10:29–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA 2001 Ectopic expression of MyD118/Gadd45/CR6 (Gadd45β/α/γ) sensitizes neoplastic cells to genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis. Int J Oncol 18:749–757 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Pickin KA, Bose R, Jura N, Cole PA, Kuriyan J 2007 Inhibition of the EGF receptor by binding of MIG6 to an activating kinase domain interface. Nature 450:741–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vairapandi M, Balliet AG, Fornace Jr AJ, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA 1996 The differentiation primary response gene MyD118, related to GADD45, encodes for a nuclear protein which interacts with PCNA and p21WAF1/CIP1. Oncogene 12:2579–2594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debes JD, Tindall DJ 2002 The role of androgens and the androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett 187:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman BJ, Feldman D 2001 The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 1:34–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balk SP, Knudsen KE 2008 AR, the cell cycle, and prostate cancer. Nucl Recept Signal 6:e001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Wang Z 2004 Gadd45γ is androgen-responsive and growth-inhibitory in prostate cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 213:121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Ly LH, Peehl DM, Feldman D 1997 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 actions in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells are androgen-dependent. Endocrinology 138:3290–3298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beildeck ME, Islam M, Shah S, Welsh J, Byers SW 2009 Control of TCF-4 expression by VDR and vitamin D in the mouse mammary gland and colorectal cancer cell lines. PLoS One 4:e7872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pálmer HG, González-Sancho JM, Espada J, Berciano MT, Puig I, Baulida J, Quintanilla M, Cano A, de Herreros AG, Lafarga M, Muñoz A 2001 Vitamin D(3) promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of β-catenin signaling. J Cell Biol 154:369–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Z, Takekawa M, Ge Q, Saito H 2007 Activation of MTK1/MEKK4 by GADD45 through induced N-C dissociation and dimerization-mediated trans autophosphorylation of the MTK1 kinase domain. Mol Cell Biol 27:2765–2776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam N, Vairapandi M, Zhang W, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA 2001 Interaction of CR6 (GADD45γ) with proliferating cell nuclear antigen impedes negative growth control. J Biol Chem 276:2766–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying J, Srivastava G, Hsieh WS, Gao Z, Murray P, Liao SK, Ambinder R, Tao Q 2005 The stress-responsive gene GADD45G is a functional tumor suppressor, with its response to environmental stresses frequently disrupted epigenetically in multiple tumors. Clin Cancer Res 11:6442–6449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Sun H, Danila DC, Johnson SR, Zhou Y, Swearingen B, Klibanski A 2002 Loss of expression of GADD45γ, a growth inhibitory gene, in human pituitary adenomas: implications for tumorigenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1262–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Li T, Shao Y, Zhang C, Wu Q, Yang H, Zhang J, Guan M, Yu B, Wan J 2010 Semi-quantitative detection of GADD45-γ methylation levels in gastric, colorectal and pancreatic cancers using methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 136:1267–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordan-McCombs S, Brown T, Wang WL, Gaupel AC, Welsh J, Tenniswood M 2010 Tumor progression in the LPB-tag transgenic model of prostate cancer is altered by vitamin D receptor and serum testosterone status. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 121:368–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao BY, Hu YC, Ting HJ, Lee YF 2004 Androgen signaling is required for the vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition in human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 23:3350–3360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ES, Maiorino CA, Roos BA, Knight SR, Burnstein KL 2002 Vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition of an androgen-ablated LNCaP cell line model of human prostate cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 186:69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbrecht HJ, Chen ML, Hodam TL, Boltz MA 1997 Induction of 24-hydroxylase cytochrome P450 mRNA by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and phorbol esters in normal rat kidney (NRK-52E) cells. J Endocrinol 153:199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou YR, Nazarova N, Talonpoika R, Tuohimaa P 2005 5α-Dihydrotestosterone inhibits 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced expression of CYP24 in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate 63:222–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Li P, Fornace Jr AJ, Nicosia SV, Bai W 2003 G2/M arrest by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in ovarian cancer cells mediated through the induction of GADD45 via an exonic enhancer. J Biol Chem 278:48030–48040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YW, Staal B, Su Y, Swiatek P, Zhao P, Cao B, Resau J, Sigler R, Bronson R, Vande Woude GF 2007 Evidence that MIG-6 is a tumor-suppressor gene. Oncogene 26:269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackel PO, Zwick E, Prenzel N, Ullrich A 1999 Epidermal growth factor receptors: critical mediators of multiple receptor pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol 11:184–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioeli D, Mandell JW, Petroni GR, Frierson Jr HF, Weber MJ 1999 Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res 59:279–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrian-Shai R, Chen CD, Shi T, Horvath S, Nelson SF, Reichardt JK, Sawyers CL 2007 Insulin growth factor-binding protein 2 is a candidate biomarker for PTEN status and PI3K/Akt pathway activation in glioblastoma and prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:5563–5568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez CJ, Vanweelden K, Byrne I, Welsh J 1996 Characterization of a vitamin D3-resistant MCF-7 cell line. Endocrinology 137:400–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez CJ, Byrne BM, Romu S, Valrance M, Welsh J 2003 Induction of apoptosis by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in MCF-7 vitamin D3-resistant variant can be sensitized by TPA. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 84:199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polek TC, Stewart LV, Ryu EJ, Cohen MB, Allegretto EA, Weigel NL 2003 p53 is required for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced G0 arrest but is not required for G1 accumulation or apoptosis of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Endocrinology 144:50–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagbala AA, Moser MT, Johnson CS, Trump DL, Foster BA 2007 Characterization of vitamin D insensitive prostate cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 103:712–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao BY, Ting HJ, Hsu JW, Yasmin-Karim S, Messing E, Lee YF 2010 Down-regulation of NF-κB signals is involved in loss of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) responsiveness. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 120:11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbini LF, Wang Y, Czibere A, Correa RG, Cho JY, Ijiri K, Wei W, Joseph M, Gu X, Grall F, Goldring MB, Zhou JR, Libermann TA 2004 NF-κB-mediated repression of growth arrest- and DNA-damage-inducible proteins 45α and γ is essential for cancer cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:13618–13623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.