Abstract

This study examined the associations between dating partners' misuse of prescription medications and the implications of misuse for intimate relationship quality. A sample of 100 young adult dating pairs completed ratings of prescription drug use and misuse, alcohol use, and relationship quality. Results indicated positive associations between male and female dating partners' prescription drug misuse, which were more consistent for past-year rather than lifetime misuse. Dyadic associations obtained via actor-partner interdependence modeling further revealed that individuals' prescription drug misuse holds problematic implications for their own but not their partners' intimate relationship quality. Models accounted for individuals' alcohol-related risk and medically-appropriate prescription drug use, suggesting the independent contribution of prescription drug misuse to reports of relationship quality. The findings highlight the importance of considering young adults' substance behaviors in contexts of their intimate relationships.

Keywords: dyadic data analysis, prescription drug misuse, relationship satisfaction, young adults

Prescription drug misuse, particularly among teenagers and young adults, is a growing public health concern in the United States (Hertz & Knight, 2006; National Institute of Drug Abuse, 2005). Indeed, while the use of illicit drugs by teenagers has remained constant or decreased in recent years, the misuse of prescription medications has increased during the same time period (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2008). To date, research on the use of prescription drugs for non-medical purposes (i.e., either taking prescription medication intended for another person, or in a way other than intended by a physician) has focused on establishing prevalence rates and identifying individual correlates of the behavior (e.g., demographic characteristics; McCabe, Teter, & Boyd, 2004; Simoni-Wastila, Ritter, & Strickler, 2004). Existing research has provided valuable information about the extent of misuse and identified individuals who are at-risk for misuse, although questions remain concerning the interpersonal contexts in which individuals might be more likely to misuse prescription medications and whether misuse is associated with the quality of relationships. The interpersonal contexts of young adults are expected to be particularly salient as relational focus shifts from maintaining peer relationships to establishing romantic partnerships (Arnett, 2000). The present study elucidates a central interpersonal context of risky health behaviors by examining interrelations between dating partners' prescription drug misuse, and testing whether individuals' misuse has implications for the quality of intimate relationships (i.e., attachment levels, negative evaluations, positive relationship functioning).

Prescription Drug Misuse among Young Adults

Data from national studies indicate that 20% of individuals aged 12 and older in the U.S. report at least one occasion of prescription drug misuse in their lifetime (Colliver, Kroutil, Dai, & Gfroerer, 2006). Notably, young adults aged 18-25 years exhibit a higher misuse prevalence than other age groups (Lessenger & Feinberg, 2008), with this group's rates of past-month nonmedical use of prescription drugs having increased steadily since 2002 (Critser, 2005; Sprague, 2009; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2008). Using large, representative studies, McCabe and colleagues have been able to examine prevalence rates of young adults' nonmedical use of different classes of prescription drugs. Specifically, using results from a 2001 mail survey of U.S. 4-year colleges, McCabe, Knight, Teter, and Wechsler (2005) documented prevalence rates of the non-medical use of prescription stimulants generally prescribed for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (e.g., Ritalin, Adderall) as 6.9% for lifetime, 4.1% for past-year, and 2.1% for past-month. This survey further revealed rates of the misuse of prescription pain medication as 12% for lifetime and 7% for past-year (McCabe, Teter, Boyd, Wechsler, & Knight, 2005). Drawing on data collected in 2003, college students' prevalence rates for prescription drug misuse within the past year were highest for pain medication, followed by stimulants, sedative or anxiety medication, and sleeping medication (McCabe, Teter, & Boyd, 2006).

McCabe and his colleagues have further elucidated correlates of individuals who misuse prescription drugs. In general, males show greater risk for misusing than women, even though women are prescribed more medication (Teter, McCabe, Cranford, Guthrie, & Boyd, 2005). Most concerning, young adults who misused prescription medications were also more likely to use alcohol, cigarettes, and illicit drugs, and engage in other risky behaviors such as drunk driving and polydrug use (McCabe & Boyd, 2005; McCabe, Knight, et al., 2005; McCabe & Teter, 2007; McCabe, Teter, Boyd, et al., 2005). Taken together, findings from studies of the prevalence and individual correlates of prescription drug misuse indicate that misusing prescription medication is a significant concern among young-adult college students with serious implications for health and well-being (McCabe, Teter, & Boyd, 2006).

Prescription Drug Misuse in the Context of Intimate Relationships

Despite this increasing awareness of the rates and individual-level correlates of prescription drug misuse, the interpersonal contexts of substance behaviors among young adults have received scant attention. In one study, Sung, Richter, Vaughan, Thom, and Johnson (2005) reported that teenagers aged 12-17 were more likely to misuse opioids (i.e., prescription pain medications) if their friends used illicit drugs. However, research has suggested that individuals become increasingly resistant to the influence of peer pressure from friendships between the ages 14 and 18 (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007), whereas the romantic partnership becomes increasingly salient during early adulthood. Specifically, in Etcheverry and Agnew's (2008) recent study of 18- to 25-year-old 1st-year college students' smoking behavior, the smoking behavior and smoking approval of dating partners and friends were both independently and positively associated with the likelihood of smoking, yet dating partners' smoking behavior and norms evidenced a relatively stronger predictive effect on smoking.

A great deal of the research that documents a tendency for partners to influence each other's health and substance use behaviors has relied on examination of samples of married couples (e.g., drinking behaviors; Leonard & Eiden, 1999). Research has consistently shown spousal behavior and attitudes to predict individual health behavior, at times more so than the individual's own motivation, for example, in adherence to self-initiated and prescribed exercise programs (Dishman, Sallis, & Orenstein, 1985) and in women's breastfeeding decisions and behavior (Rempel & Rempel, 2004). Regarding substance-related behaviors, husbands' and wives' drinking levels are significantly related in a positive direction in both community-based and at-risk samples (Keller, Cummings, Davies, & Mitchell, 2008; Kelly & Halford, 2006). In addition, Clark and Etilé (2006) documented spouses' positively correlated smoking behavior.

Although rarely studied systematically among dating partners, there is evidence that individuals are more likely to engage in risky health behaviors in general (e.g., cigarette use) if their dating partner does (Etcheverry & Agnew, 2008). As an example, a study of 18- to 29-year-old African American women indicated that having a partner who resisted using condoms placed women at a 3-fold risk for not using condoms, which has serious implications for health risk and disease prevention (Wingood & DiClemente, 1998). Following this initial evidence that dating partners play a role in individuals' health and substance use behavior, the present study tested within-couple linkages between male and female partners' prescription drug misuse.

Research based primarily on married couples underscores the bi-directional interplay between substance behaviors and intimate relationship functioning. Whisman (2007) utilized a large U.S. population-based survey to examine linkages between marital distress and DSM Axis I psychiatric disorders. Individuals' marital distress was linked to a greater likelihood of having any substance use disorder, and an increased likelihood of alcohol use disorders in particular, with results consistent for men and women. Marshal (2003) reviewed 60 studies that tested associations between alcohol use and marital functioning, and summarized linkages between drinking and three domains of marital functioning: marital dissatisfaction, communication marked by negativity and low problem solving levels, and physical aggression. Recent work indicates that spousal drinking is further associated with specific maladaptive expressions of marital conflict over time: wife and husband drinking at baseline were associated with marital stonewalling (i.e., refusal to work together) a year later, and husband baseline drinking was linked to higher levels of verbal and physical aggression over time (Keller et al., 2008). Among a college-based dating sample, pairs who were characterized by problematic drinking showed higher rates of sexual coercion, threatened or forced sex, and the male partner's perpetration of sexual aggression (Rapoza & Drake, 2009). The present research tested associations between individuals' prescription drug misuse and their own and their partners' relationship quality (broadly conceptualized) to enhance our understanding of the role of young adults' substance use in widely relevant aspects of intimate relationship contexts.

The Current Study

The current study tested two main questions regarding the misuse of prescription medications among young adult dating partners:

First, does misuse of prescription drugs by male and female partners demonstrate a positive association? Given the documented similarity in other risky health behaviors expressed by marital and dating partners (e.g., Clark & Etilé, 2006; Etcheverry & Agnew, 2008), a positive correlation between dating partners' misuse of prescription medications, in terms of both the likelihood of misuse and the level of misuse, was hypothesized. Effects were expected to be more consistent for individuals' past-year misuse compared to lifetime misuse due to temporal intersection with the intimate relationship context.

Second, are males' and females' levels of misuse of prescription drugs associated with their own and their partners' quality of dating relationships broadly defined? First, level of prescription drug misuse was expected to demonstrate linkages with emotional closeness and attachment, or the tendency for partners to seek and provide support during times of stress (Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992). Specifically, prescription drug misuse was hypothesized to positively relate to partners' avoidant and anxious attachment styles. Consistent with evidence that substance use is generally linked with maladaptive relationship functioning, level of prescription drug misuse was hypothesized to relate to more negative evaluations of the partner and the relationship and to lower levels of relationship satisfaction. Based on previous research that documented a stronger connection between psychological well-being and relationship functioning for females than males (Fincham, Beach, Harold, & Osborne, 1997), the prescription drug misuse-relationship quality linkages were expected to be more consistent for female partners. Again, individuals' past-year misuse was predicted to be more consistently related than lifetime misuse to relationship quality. Given the relative lack of attention in the literature to partner effects, individuals' misuse of prescription drugs was expected to be more consistently associated with their own relationship quality outcomes compared to those of their partners.

Past research has indicated a substantial co-occurrence of alcohol use and misuse of prescription medication (McCabe, Cranford, & Boyd, 2006), with one study reporting individuals' likelihood of misusing prescription drugs to increase as a function of the severity of alcohol use disorders (McCabe, West, & Wechsler, 2007). In light of the relatively high rates of young adults' alcohol use (O'Malley & Johnston, 2002), the current analyses controlled for individuals' alcohol use to ensure that the effects of prescription drug misuse were not attributable to dating partners' broader substance tendencies. In addition, all analyses controlled for individuals' medically-appropriate prescription drug use.

Method

Participants and Procedure

A sample of 100 heterosexual dating couples was recruited from a medium-sized town in the Midwest via flyers posted in community restaurants, stores, and residences. Flyers advertised opportunities for dating couples to participate in a study of “the connections between romantic relationships and individuals' well-being.” Couples were required to be dating exclusively for a minimum of 1 month. In addition, participants were not eligible if they were married currently, had been married previously, or had children. Of the 244 couples who made an initial telephone or e-mail contact to express interest, 101 consented to participate, 61 were not eligible (due to missing the study's end date, being in a long-distance relationship that prohibited a laboratory visit, or having been married before, etc.), 46 could not be reached for follow-up, and 36 expressed non-interest or inability to schedule a laboratory visit. One same-sex couple was excluded from the present study due to the focus on within-couple linkages between male and female partners prescription drug misuse.

The resulting sample of 100 couples had been dating for an average of 22.7 months (SD = 18.0 months, range = 1-72 months) at the time of their laboratory visit. Male and female participants' ages averaged 21.0 years (SD = 3.1 years, range = 18-36) and 20.3 years (SD = 2.4 years, range = 18-30), respectively. Males' and females' respective racial and ethnic distributions were as follows: 82/85 European American/White, 0/2 African American/Black, 6/6 Asian American/Pacific Islander, 4/2 Hispanic/Latino, 4/3 Biracial, and 4/2 identified as Other. Most participants (82% of males, 90% of females) reported either undergraduate or graduate student status. In addition, 22% of the couples reported living together. Couples attended a laboratory-based session that typically lasted 1.5 hr and was facilitated by trained research assistants. During the session, couples completed multiple procedures, including problem-solving discussions and questionnaires. The university's Institutional Review Board approved the study. Participants received $10 each for completing the study.

Measures

Prescription drug and alcohol use

Individuals' medical and nonmedical use of prescription drugs was assessed using procedures described by McCabe (2008). Lifetime medical use of prescription medication was collected via participants' responses to the following question: “Based on a doctor's prescription, on how many occasions in your lifetime have you used the following types of drugs?” The question was asked for each of the following classes of prescription drugs: (1) sleeping medication (e.g., Ambien [zolpidem], Halcion [triazolam], Restoril [temazepam], temazepam, triazolam); (2) sedative or anxiety medication (e.g., Ativan [lorazepam], Xanax [alprazolam], Valium [diazepam], Klonopin [clonazepam], diazepam, lorazepam); (3) stimulant medication (e.g., Ritalin [methylphenidate], Dexedrine [dextroamphetamine], Adderall [dextroamphetamine and amphetamine], Concerta [methylphenidate], methylphenidate); and (4) pain medication (i.e., opioids such as Vicodin [hydrocone and acetaminophen], OxyContin [oxycodone], Tylenol 3 [acetaminophen] with codeine, Percocet [oxycodone and acetaminophen], Darvocet [propoxyphene and acetaminophen], morphine, hydrocodone, oxycodone). Participants answered the question for the 4 drug classes on a scale consisting of 0 (never), 1 (1-2 occasions), 2 (3-5 occasions), 3 (6-9 occasions), 4 (10-19 occasions), 5 (20-39 occasions), and 6 (40 or more occasions). The same variables were created based on a variant of the question that asked about how many times prescriptions were used in the past year.

Lifetime nonmedical use of prescription medication was collected via individuals' responses to following question: “Sometimes people use prescription drugs that were meant for other people, even when their own doctor has not prescribed it for them. On how many occasions in your lifetime have you used the following types of drugs, not prescribed to you?” The question was asked for each of the 4 classes of prescription drugs listed above. The same variables were created based on the question that asked about how many times prescriptions were misused in the past year.

Both partners reported their recent alcohol use, alcohol dependence symptoms, and alcohol-related problems using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001), which was developed by the World Health Organization and is used widely by practitioners to assess alcohol consumption and problems. Each of the 10 items on the AUDIT is rated on a scale of 0 to 4, and the item scores are summed to determine the level of risk related to the respondent's alcohol consumption. Sample items include “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?” and “How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking?” Internal consistency of the AUDIT was satisfactory for males (α = .74) and females (α = .72).

Intimate relationship quality

Participants' attachment styles were measured using Simpson et al.'s (1992) questionnaire. Individuals rated the extent to which they agree with 13 statements about their feelings toward romantic partners on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Examples include “I don't like people getting too close to me” and “I rarely worry about my partner(s) leaving me.” Scoring the questionnaire results in an avoidant (compared to secure) attachment index (8 items) and an anxious (compared to non-anxious) attachment index (5 items). Previous research has documented the reliability and validity of this scale among dating couples (Simpson et al., 1992). In the present study, internal consistency coefficients for avoidant attachment scores and anxious attachment scores, respectively, were both .81 and .63 for males and females.

Participants completed the negative relational quality dimension of the Positive and Negative Quality in Marriage Scale (NMQ; Fincham & Linfield, 1997). Individuals were instructed to ignore their positive sentiments and rate on a scale ranging from 1 (low) to 10 (high) 3 items: negative qualities of their partner, negative feelings towards their partner, and negative feelings about their relationship. Responses were summed with higher values indicating greater negative relationship evaluations. This scale corresponds with widely-used relationship adjustment questionnaires and behavioral observations, and demonstrates sound psychometric properties in married and non-married samples (Fincham & Linfield, 1997; Mattson, Paldino, & Johnson, 2007). Internal consistency was satisfactory for males (α = .85) and females (α = .82).

Participants provided reports of the satisfaction they feel in their current relationship using the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI; Funk & Rogge, 2007), which was developed using item-response theory. The version used in the current study includes 32 items, which are rated on differential response scales, and results in possible scores that range from 0 to 161. The measure correlated with standard relationship assessments in a large sample of dating and married participants (Funk & Rogge, 2007). In the present study, internal consistency of the CSI was good for males (α = .94) and females (α = .93).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the frequency of prescription drug use and misuse reported by male and female partners. In the present study, 36% of males and 37% of females endorsed lifetime prescription drug misuse; 29% of both males and females endorsed past-year misuse. Variables were also created to reflect the level of prescription drug misuse by averaging individuals' responses to the questions regarding lifetime and past-year misuse of the 4 prescription drug classes described above. The average levels of lifetime misuse for males and females, respectively, were 0.45 (SD = 0.96, range = 0-5.25) and 0.33 (SD = .60, range = 0-2.5). Past-year misuse levels for males' and females' were 0.27 (SD = 0.67, range = 0-4) and 0.18 (SD = 0.36, range = 0-1.75). As recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), a log transformation was applied to individuals' lifetime and past-year levels of prescription drug misuse to reduce the strong positive skewness of the variables. Subsequent analyses retained these transformed values of prescription drug misuse (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables for males and females). Paired-samples t-tests indicated that male and female partners' levels of lifetime and past-year prescription drug misuse were not significantly different from each other, t(99) = 0.80, t(99) = 1.12, ps > .05, respectively.

Table 1.

Frequency of Prescription Drug Use by Male and Female Dating Partners

| Prescription Drug Classa | Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime | Past-Year | |||

| Male Partnersb | Female Partnersc | Male Partnersb | Female Partnersc | |

| Nonuse | 17 | 12 | 41 | 45 |

| Medical use only | 47 | 51 | 30 | 26 |

| Medical and nonmedical use | 33 | 33 | 15 | 18 |

| Nonmedical use only | 3 | 4 | 14 | 11 |

Results are combined across the 4 classes of prescription drugs, including pain, sleeping, sedative/anxiety, and stimulant medications.

n = 50.

n = 50.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations of Measures of Prescription Drug Misuse and Use, Alcohol Use, and Intimate Relationship Quality

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lifetime prescription drug misuse | -- | .89** | .22* | .22* | .51** | .28** | -.05 | -.04 | -.11 |

| 2. Past-year prescription drug misuse | .85** | -- | .21* | .28** | .44** | .24* | -.08 | -.10 | -.01 |

| 3. Lifetime prescription drug use (covariate) | .41** | .25** | -- | .69** | .22* | .04 | .03 | .01 | .13 |

| 4. Past-year prescription drug use (covariate) | .28** | .18† | .86** | -- | .14 | .12 | .04 | .05 | .13 |

| 5. Risk related to alcohol (AUDIT) | .20* | .21* | .20* | .16 | -- | .17† | .01 | -.02 | -.07 |

| 6. Avoidant attachment | .20* | .24* | .14 | .03 | -.002 | -- | .26** | .20† | -.39** |

| 7. Anxious attachment | .01 | .06 | .09 | .06 | .25* | .07 | -- | .06 | -.25* |

| 8. Negative relationship evaluations (NMQ) | .10 | .19† | .001 | -.04 | .02 | .09 | .17† | -- | -.56** |

| 9. Relationship satisfaction (CSI) | -.15 | -.21* | -.12 | -.11 | -.11 | -.16 | -.26* | -.68** | -- |

| Female M | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 5.82 | 24.17 | 13.27 | 10.01 | 137.14 |

| Female SD | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 3.20 | 8.79 | 5.39 | 5.02 | 16.90 |

| Female Range | 0-0.54 | 0-0.44 | 0-4.00 | 0-3.00 | 1-15 | 8-50 | 5-29 | 3-30 | 86-161 |

| Male M | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 7.79 | 23.33 | 12.67 | 10.43 | 136.31 |

| Male SD | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.94 | 0.56 | 4.77 | 8.61 | 4.68 | 5.36 | 16.99 |

| Male Range | 0-0.80 | 0-0.70 | 0-5.50 | 0-2.75 | 0-23 | 8-47 | 5-25 | 3-24 | 72-161 |

Note. Intercorrelations for female partners (n = 50) are presented below the diagonal, and intercorrelations for male partners (n = 50) are presented above the diagonal. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; NMQ = Negative Marital Quality; CSI = Couples Satisfaction Index.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

Does Misuse of Prescription Drugs by Dating Partners Demonstrate a Positive Association?

To test relations between dating partners' prescription drug misuse across the lifetime and in the past year, a series of partial correlations accounting for appropriate use of prescription medication was estimated. Results indicated that the likelihood of partners' lifetime prescription drug misuse (0 = no misuse occurred, 1 = misuse occurred) was not associated, r(100) = .15, p = .147, but the likelihood of partners' past-year misuse was positively linked, r(100) = .28, p = .005. Next, partial correlations were estimated to test associations between levels of partners' prescription drug misuse, reported on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (40 or more occasions). Findings indicated that male and female partners' levels of prescription drug misuse were positively correlated, both across the lifetime, r(100) = .36, p < .001, and in the past year, r(100) = .42, p < .001, again accounting for appropriate use of prescription drugs. Taken together, analyses revealed positive correlations between partners' prescription drug misuse, with more consistent associations observed between partners' recent as compared to lifetime misuse.

Robustness Test: Does Partners' Prescription Drug Misuse Reflect General Substance Use Tendencies?

Scores between 8 and 15 on the AUDIT indicate a medium level of alcohol problems, and scores above 16 represent a high level of alcohol problems (Babor et al., 2001). In the present sample, 22% of females had medium level of alcohol problems and none evidenced high levels of alcohol problems; among males, 39% reported medium problem levels and 5% evidenced high levels of alcohol problems. Dyadic correlation analyses were conducted using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) analytic framework to test whether alcohol use was associated with prescription drug misuse for male and female partners. As described in detail below, the APIM analyses accounted for positive covariation in partners' level of alcohol use, residual covariation in partners' prescription drug misuse, and level of appropriate medical use of prescription drugs. Results revealed a positive association between levels of alcohol use and prescription drug misuse among males but not females, based on both lifetime (males: estimate = 13.64, SE = 2.38, p < .001; females: estimate = 3.34, SE = 2.24, p = .137) and past-year (males: estimate = 13.81, SE = 3.36, p < .001; females: estimate = 4.85, SE = 3.34, p = .147) misuse. Further, addressing the robustness of the results of the first research question, even when controlling for individuals' medical use of prescription drugs and alcohol use, male and female partners' levels of lifetime, r(100) = .37, p < .001, and past-year, r(100) = .39, p < .001, prescription drug misuse remained significantly inter-correlated. Accordingly, the following tests of associations between prescription drug misuse and intimate relationship quality controlled for individuals' AUDIT scores in addition to medically-appropriate use of prescription drugs.

Is Prescription Drug Misuse Associated with Intimate Relationship Quality?

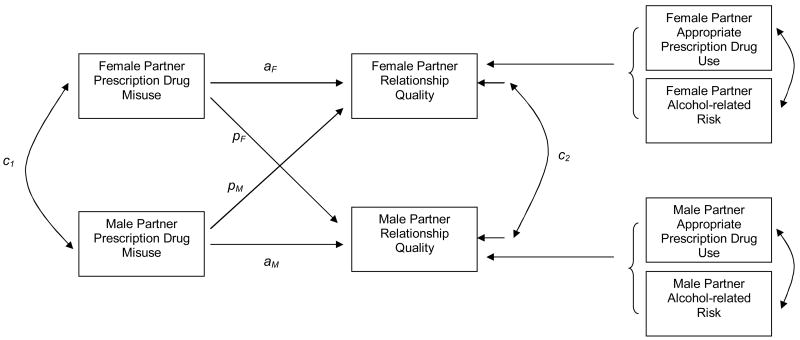

Associations between prescription drug misuse and intimate relationship quality were tested using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Cook & Kenny, 2005; Kashy & Kenny, 2000). In brief, the APIM is a dyadic data analytic approach that simultaneously estimates the effect that a respondent's independent variable has on his or her own dependent variable (i.e., actor effect) and on his or her partner's dependent variable (i.e., partner effect), controlling for shared variance in the partners' independent variables and dependent variables and accounting for potential covariates (Campbell, Simpson, Kashy, & Rholes, 2001). APIMs have been utilized widely to examine actor and partner effects in couple relationships (e.g., Kilpatrick, Bissonnette, & Rusbult, 2002), with the interpretation of these actor and partner effects dependent on the particular variables included in the model. In the present study, males' and females' prescription drug misuse levels were considered as predictors of their own and their partners' intimate relationship qualities. APIMs were fit using Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS, v. 17.0; Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999). Traditional model-fit statistics are not presented because APIMs are recursive (Cook & Kenny, 2005). As shown in Figure 1, APIMs simultaneously estimated the associations between males' and females' prescription drug misuse and their own intimate relationship quality (paths aM and aF, respectively) and between males' and females' prescription drug misuse and their partner's intimate relationship quality (paths pM and pF, respectively), while accounting for the positive covariation in male and female partners' level of misuse (path c1), the residual covariation in partners' relationship characteristics not explained by the model (path c2), and the interrelated covariates of individuals' appropriate use of prescription medication and alcohol-related risk.

Figure 1.

APIM to test associations between prescription drug misuse and intimate relationship quality in a dyadic analytic framework, controlling for appropriate prescription drug use and alcohol-related risk.

APIM results that provide estimates of the associations between prescription drug misuse and intimate relationship quality beyond effects due to more general substance tendencies (i.e., appropriate use of prescription medication, problematic drinking behavior,) are shown in Table 3. Males' lifetime prescription drug misuse was positively associated with their own avoidant attachment styles, whereas the positive link between males' past-year misuse and their avoidant attachment approached statistical significance. Females' past-year prescription drug misuse levels were significantly related to their higher levels of negative relational evaluations and lower levels of relationship satisfaction. In addition, there was a marginal association between females' past-year prescription drug misuse and their own avoidant attachment styles. Neither male nor female prescription drug misuse in the past year or across the lifetime was related to anxious attachment levels (see Table 3). In sum and consistent with predictions, linkages between prescription drug misuse and relationship functioning emerged more consistently for females than males. Also consistent with predictions, partners' own relationship quality was more closely linked with recent as compared to lifetime substance behavior. Finally, no significant partner effects were documented (see Table 3).

Table 3.

APIM Results: Associations between Prescription Drug Misuse and Intimate Relationship Quality

| Actor Effects | Partner Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Partners, aM | Female Partners, aF | Male Partners, pM | Female Partners, pF | |

| Y = Avoidant attachment | ||||

| Past-year prescription drug misuse | 11.35† (6.53) | 15.61† (9.07) | 5.99 (6.63) | 4.31 (8.94) |

| Lifetime prescription drug misuse | 9.91* (4.77) | 6.68 (6.11) | 7.65 (4.94) | 7.29 (5.90) |

| Y = Anxious attachment | ||||

| Past-year prescription drug misuse | -4.58 (3.65) | 0.13 (5.60) | 0.24 (4.10) | 3.54 (4.99) |

| Lifetime prescription drug misuse | -2.55 (2.71) | -4.20 (3.72) | 3.95 (3.01) | 2.08 (3.36) |

| Y = Negative relationship evaluations | ||||

| Past-year prescription drug misuse | -6.65 (4.15) | 12.79* (5.23) | -5.53 (3.82) | 6.99 (5.68) |

| Lifetime prescription drug misuse | -2.69 (3.11) | 3.91 (3.59) | -0.58 (2.90) | 3.35 (3.84) |

| Y = Relationship satisfaction | ||||

| Past-year prescription drug misuse | 7.49 (13.23) | -36.71* (17.78) | 13.28 (12.99) | -16.61 (18.11) |

| Lifetime prescription drug misuse | -7.89 (9.82) | -9.10 (12.10) | -4.57 (9.79) | -1.99 (12.14) |

Note. Models control for covariance between male and female partners' prescription drug misuse, relationship quality residuals, and appropriate medical use of prescription drugs and alcohol-related risk (see Fig. 1). Table reports unstandardized coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Italicized letters correspond to pathways shown in Figure 1.

p < .09.

p < .05.

Discussion

The present study is among the first to examine the contextual underpinnings of prescription drug misuse, focusing on young adults' intimate relationships. This study extended previous research that documented prevalence rates and individual correlates of young adults' misuse of prescription medication by testing within-couple misuse associations and examining associations between individuals' misuse and intimate relationship qualities. In terms of the first research question, analyses revealed a positive association between dating partners' likelihood of misusing prescription drugs during the past year, but not over the course of the lifetime. However, levels of both past-year and lifetime misuse were positively associated between dating partners. Thus, the first question's hypothesis that partners' nonmedical use of prescription medication would be inter-related, and more consistently linked for recent misuse, received support. This finding aligns with reports of married partners expressing similar substance use behaviors (e.g., Keller et al., 2008), and encourages continued investigation of young adults' intimate relationships as a context of prescription drug misuse and other substance behaviors.

Indeed, reasons why partners demonstrate similarity in substance use and other behaviors comprise an extensive area of study. Proposed mechanisms for this general tendency toward concordance between partners include assortative mating and shared attitudes (Hohmann-Marriott, 2006; Luo & Klohnen, 2005). Notably, Clark and Etilé (2006) found spouses' positively correlated smoking behavior to more closely reflect assortative mating--or the notion that partners' coupling is due to similarity or matching on one or more characteristics or behaviors rather than to chance alone (Buss, 1984)--than reasons explained by theories of social learning or shared decision making. In further support of a process that may reflect assortative mating, Leonard and Eiden (2007) reviewed several studies that indicate a reciprocal interplay between partners' drinking behaviors among married couples, whereby partners' drinking patterns were similar and demonstrated spousal influence over time. Increased access or availability may also underlie partners' similarity in prescription drug misuse, given that most individuals obtain diverted prescription medication from friends or family members (McCabe, Teter, & Boyd, 2005). Nevertheless, the directionality of partners' similarity in misuse of prescription medications awaits testing in longitudinal data to shed light on whether partners select along prescription drug misuse as an indicator of substance behavior, or whether one partner's misuse leads to the development of the other's misuse over time.

Turning to the second research question of whether individuals' levels of prescription drug misuse were associated with intimate relationship quality, male and female partners' misuse was positively linked to their own avoidant attachment styles (marginal for females), but not to their self-rated anxious attachment, which did not meet commonly accepted levels of internal consistency in the present study (Streiner, 2003). The findings thus suggest that prescription drug misuse, similar to alcohol use, may reflect a coping strategy that individuals engage in to maintain an emotional and physical distance from a relational partner (McNally, Palfai, Levine, & Moore, 2003). Alternatively, the findings may point to prescription drug misuse as a substance behavior that hampers individuals' abilities to develop secure romantic attachments, although longitudinal investigations are clearly needed to clarify the direction of the association. In addition, level of prescription drug misuse was more consistently associated with relationship functioning for females than males, with females' past-year prescription drug misuse associated with their higher levels of negative relationship evaluations and lower levels of relationship satisfaction. The findings again suggest either that females who are unhappy in their romantic relationships utilize certain substance behaviors over time, or that females' misuse of prescription medication leads to their diminished relationship quality, both of which also require further testing. The fact that partner effects were not documented implies that partners' prescription drug misuse did not contribute to relationship functioning beyond individuals' own substance behaviors. However, additional research should test whether an alternate conceptualization of dyadic substance behavior, such as the discrepancy between male and female partners' prescription drug misuse (Homish & Leonard, 2007), accounts for relationship quality. Finally, alternate explanations involving predisposing mental health factors (i.e., personality disorders, psychiatric symptoms) as predictors of both substance abuse and intimate relationship problems await empirical investigation among samples of dating couples.

Importantly, the current study extends previous research that has examined linkages between other substance use (including alcohol) and relationship functioning. Notably, the present study's analytic approach was designed to ensure that the results based on prescription drug misuse do not simply reflect a correlate of alcohol, which has been the focus of investigation among young adults. That is, misuse of prescription medication by males and females was inter-related, and the misuse was associated with relationship functioning (particularly for females) beyond any effects due to individuals' alcohol use. The present study's findings indicate that prescription drug misuse warrants further study as a risky health behavior that occurs both as a unique behavior and n conjunction with alcohol among young adult samples. Confidence in the study's findings is strengthened by conducting analyses in a dyadic data framework, which appropriately modeled partner effects and further controlled for the medically-appropriate use of prescription drugs, thereby partialling out effects due to partner interdependence and general substance tendencies.

The present study provides a foundation for future investigations to adopt a process-oriented approach. To explicate the mechanisms that link partners' prescription drug misuse to intimate relationship adjustment, the role of partners' problem solving abilities and coping styles could be explored as potential mediators. Specifically, partners' high levels of negative coping strategies might account for the substance use-relationship functioning linkage (Bodenmann, Pihet, & Kayser, 2006). Moderating tests are also needed to identify factors that amplify the likelihood of such linkages. Testing individuals' mental health as a moderator might reveal that people who misuse prescription drugs in the context of elevated depressive symptoms display the most impaired intimate relationship functioning.

Clarifying the processes and risk factors underlying dating partners' substance use in close relationship contexts will enhance our ability to identify and treat individuals and couples who experience a negative interplay between individual functioning and relationship distress (Fals-Stewart, Birchler, & O'Farrell, 2003). Underscoring the possible treatment benefits of concentrating on the intimate relationship context, couples therapy has demonstrated greater efficacy than individual therapy as a treatment for male and female partners' alcohol and drug problems (e.g., Fals-Stewart & Lam, 2008; McCrady, Epstein, Cook, Jensen, & Hildebrandt, 2009). Thus, gaining a better understanding of substance use and relational processes has implications for identifying, preventing, and treating problems experienced by individuals, couples, and families (Lessenger & Feinberg, 2008).

At the same time, the present study's limitations require consideration. First, the study design was cross-sectional and the convenience sample collected from the community was not representative. Compared to McCabe's (2008) probability sample, the present study included a sample that over-represents rates of prescription drug use and misuse, and under-represents nonuse rates. In particular, lifetime rates of nonuse and nonmedical use only appear to be under-reported compared to the respective past-year frequencies (see Table 1). While speculative, it is possible that when participants received instructions to think of prescription drug misuse first in their lifetime and then in the past year, they separated past-year from lifetime rather than considering the past-year behavior as part of their lifetime. Future studies should be designed to address this discrepancy. Also, the present study's measurement of prescription drug misuse (i.e., using prescription drugs that were intended for other people) was excessively narrow; the literature also includes definitions such as “any intentional use of a medication with intoxicating properties outside of a physician's prescription for a bona fide medical condition” (Compton & Volkow, 2006, p. S4) or use of drugs or medication “not under a doctor's orders” (Spoth, Trudeau, Shin, & Redmond, 2008, p. 1165). To overcome these limitations, future work should consider a more comprehensive assessment of prescription drug misuse among representative samples in designs that incorporate longitudinal and/or ecological momentary assessment methods, thereby placing less burden on participants' memories and helping to elucidate the reciprocal dynamics between intimate relationship functioning and substance behaviors as they unfold in daily life (Schwarz, 2007; Shiffman, 2007).

Next, given the focus on relational processes, all participants in the present study were dating and volunteered to participate in a study on intimate relationships, which may differentiate them from individuals in the broader population. Moreover, the present study's sample size precluded consideration of specific classes of prescription drugs; thus, future work should explore whether drug classes (e.g., pain medication vs. stimulant medication) differentially relate to relationship qualities. Although reflective of the study's location, the present study lacked significant diversity. Additional work on young adults' substance use and relationship qualities should include couples who are diverse along racial/ethnic background, student/employment status, and sexual orientation. Despite these limitations, the present findings contribute to a literature that has identified prescription drug misuse as a growing public health concern by underscoring intimate relationships as an important context of young adults' prescription drug misuse.

In recent years, the average number of yearly prescribed medications has increased from 7 to 12 per person in the United States; in the same time period, youth have demonstrated increases in self-medication, relying more on a medication-only approach to treating their problems and stressors (Crister, 2005). Moreover, the early onset of prescription drug misuse is a significant predictor of prescription drug abuse and dependence (McCabe, West, Morales, Boyd, & Cranford, 2007), and misuse of stimulant medications has been identified as a marker for potential illicit drug abuse (McCabe & Teter, 2007). Thus, there is a critical need to improve our understanding of the increasing trend of prescription drug misuse among young adults in the United States and the contexts in which it is likely to occur, which may underlie a cycle that is expected to have maladaptive, long-term consequences for intimate partner and family relationships (Leonard & Eiden, 2007).

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge support provided by the School of Human Ecology and research assistance provided by numerous undergraduate students in the UW-Madison Couples Lab. Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R03 HD057346.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/adb

References

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 user's guide. Chicago: SmallWaters Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT-The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Pihet S, Kayser K. The relationship between dyadic coping and marital quality: A 2-year longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:485–493. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM. Toward a psychology of person-environment (PE) correlation: The role of spouse selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47:361–377. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson JA, Kashy DA, Rholes WS. Attachment orientations, dependence, and behavior in a stressful situation: An application of the actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2001;18:821–843. [Google Scholar]

- Clark AE, Etilé F. Don't give up on me baby: Spousal correlation in smoking behaviour. Journal of Health Economics. 2006;25:958–978. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colliver JD, Kroutil LA, Dai L, Gfroerer JC. Misuse of prescription drugs: Data from the 2002, 2003, and 2004 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2006. DHHS Publication No SMA 06-4192, Analytic Series A-28. [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Volkow ND. Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83S:S4–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, Kenny DA. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Critser G. Generation Rx: How prescription drugs are altering American lives, minds, and bodies. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK, Sallis JF, Orenstein DR. The determinants of physical activity and exercise. Public Health Reports. 1985;100:158–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etcheverry PE, Agnew CR. Romantic partner and friend influences on young adult cigarette smoking: Comparing close others' smoking and injunctive norms over time. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:313–325. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, O'Farrell TJ. Alcohol and other substance abuse. In: Snyder DK, Whisman MA, editors. Treating difficult couples: Helping clients with coexisting mental and relationship disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Lam WKK. Brief behavioral couples therapy for drug abuse: A randomized clinical trial examining clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Families, Systems, & Health. 2008;26:377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH, Harold GT, Osborne LN. Marital satisfaction and depression: Different causal relationships for men and women? Psychological Science. 1997;8:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Linfield KJ. A new look at marital quality: Can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Funk JL, Rogge RD. Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:572–583. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz JA, Knight JR. Prescription drug misuse: A growing national problem. Adolescent Medicine Clinics. 2006;17:751–769. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann-Marriott BE. Shared beliefs and the union stability of married and cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:1015–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:43–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Various stimulant drugs show continuing declines among teens in 2008, most illicit drugs hold steady. University of Michigan News Service; Ann Arbor, MI: 2008. Dec 11, Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org. [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Kenny DA. The analysis of data and dyads from groups. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Keller PS, Cummings EM, Davies PT, Mitchell PM. Longitudinal relations between parental drinking problems, family functioning, and child adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:195–212. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, Halford WK. Verbal and physical aggression in couples where the female partner is drinking heavily. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick SD, Bissonnette VL, Rusbult CE. Empathic accuracy and accommodative behavior among newly married couples. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:369–393. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Husbands and wives drinking: Unilateral or bilateral influences among newlyweds in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999 13:130–138. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessenger JE, Feinberg SD. Abuse of prescription and over-the-counter medication. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2008;21:45–54. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.01.070071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Klohnen EC. Assortative mating and marital quality in newlyweds: A couple-centered approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:304–326. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson RE, Paldino D, Johnson MD. The increased construct validity and clinical utility of assessing relationship quality using separate positive and negative dimensions. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:146–151. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE. Screening for drug abuse among medical and nonmedical users of prescription drugs in a probability sample of college students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Boyd CJ. Sources of prescription drugs for illicit use. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1342–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ. The relationship between past-year drinking behaviors and nonmedical use of prescription drugs: Prevalence of co-occurrence in a national sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Knight JR, Teter CJ, Wechsler H. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: Prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction. 2005;100:96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Teter CJ. Drug use related problems among nonmedical users of prescription stimulants: A web-based survey of college students from a Midwestern university. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. The use, misuse and diversion of prescription stimulants among middle and high school students. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:1095–1116. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Illicit use of prescription pain medication among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Medical use, illicit use, and diversion of abusable prescription drugs. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:269–278. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.5.269-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ, Wechsler H, Knight JR. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids among U.S. college students: Prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:789–805. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Morales M, Boyd CJ, Cranford JA. Does early onset of non-medical use of prescription drugs predict subsequent prescription drug abuse and dependence? Addiction. 2007;102:1920–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Wechsler H. Alcohol-use disorders and nonmedical use prescription drugs among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:543–547. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, Jensen N, Hildebrandt T. A randomized trial of individual and couple behavioral alcohol treatment for women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:243–256. doi: 10.1037/a0014686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, Levine RV, Moore BM. Attachment dimensions and drinking-related problems among young adults: The mediational role of coping motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Drug Abuse. Prescription drugs: Abuse and addiction. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2005. NIH Publication No 05-4881, NIDA Research Report Series. [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002 14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoza KA, Drake JE. Relationships of hazardous alcohol use, alcohol expectancies, and emotional commitment to male sexual coercion and aggression in dating couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempel LA, Rempel JK. Partner influence on health behavior decision-making: Increasing breastfeeding duration. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2004;21:92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. Retrospective and concurrent self-reports: The rationale for real-time data capture. In: Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza AA, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture: Self-reports in health research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Designing protocols for ecological momentary assessment. In: Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza AA, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture: Self-reports in health research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni-Wastila L, Ritter G, Strickler G. Gender and other factors associated with the nonmedical use of abusable prescription drugs. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:1–23. doi: 10.1081/ja-120027764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Nelligan JS. Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxiety-provoking situation: The role of attachment styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:434–446. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Trudeau L, Shin C, Redmond C. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on prescription drug misuse. Addiction. 2008;103:1160–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague E. Pot no longer focus of anti-drug campaigns. 2009 July 15; Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2009/07/15/national/main5161388.shtml.

- Steinberg L, Monahan KC. Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1531–1543. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2003;80:99–103. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. Rockville, MD: 2008. NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343. [Google Scholar]

- Sung HE, Richter L, Vaughan R, Thom B, Johnson PB. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids among teenagers in the United States: Trends and correlates. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Teter CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Guthrie SK, Boyd CJ. Prevalence and motives for illicit use of prescription stimulants in an undergraduate student sample. Journal of American College Health. 2005;53:253–262. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.6.253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. Marital distress and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in a population-based national survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:638–643. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Partner influences and gender-related factors associated with noncondom use among young adult African American women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26:29–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1021830023545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]