Abstract

Background

Endothelin (ET-1) is one of the most potent vasoconstrictors, and plays a seminal role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. The current study was designed to test the hypothesis that long term treatment with an endothelin-A (ETA) receptor antagonist improves coronary endothelial function in patients with early coronary atherosclerosis.

Methods and Results

Forty seven patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors, nonobstructive coronary artery disease and coronary endothelial dysfunction were randomized in a double-blind manner to either the ETA receptor antagonist Atrasentan (10mg) or placebo for six months. Coronary endothelium-dependent vasodilation was examined by infusing acetylcholine (ACh10−6 ml/L to 10−4 mol/L) in the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD). NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (L-NMMA) was administered to a sub group of patients. Endothelium independent coronary flow reserve (CFR) was examined using intracoronary adenosine and nitroglycerin.

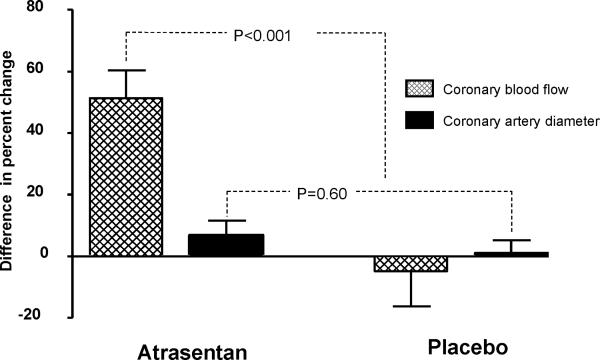

Baseline characteristics and incidence of adverse effects were similar between the two groups. There was a significant improvement in percent change of coronary blood flow (% Δ CBF) in response to ACh at six months from baseline in the Atrasentan group as compared to the placebo group (39.67 % (23.23, 68.21) vs.−2.22 % (−27.37, 15.28), P<0.001). No significant difference in the percent change of coronary artery diameter or change in coronary flow reserve (Δ CFR) was demonstrated. CBF, coronary artery diameter and the effect of L-NMMA were similar between the groups at baseline and at six months.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that six month treatment with Atrasentan improves coronary microvascular endothelial function and support the role of the endogenous endothelin system in the regulation of endothelial function in early atherosclerosis in humans.

Keywords: endothelin-1 (ET-1), Atrasentan, endothelium dependent coronary blood flow, endothelium independent coronary flow reserve, coronary artery diameter

Introduction

Endothelin -1 (ET-1) is a 21-amino acid peptide with both mitogenic and vasoconstricting properties.1 Circulating ET-1 is increased in patients with atherosclerosis2 and in the coronary circulation of patients with early atherosclerosis and coronary endothelial dysfunction.3 ET-1 contributes to the complex regulation of vascular tone through two major receptors termed endothelin-A (ETA) and endothelin-B (ETB) receptors.4 ETA receptors are located on vascular smooth muscle and mediate vasoconstriction.5 ETB receptors are located on both endothelial cells, where they mediate dilatation by releasing nitric oxide, and on smooth muscle cells, where they contribute to constriction.6

Acute blockade of ETA receptors results in coronary vasodilatation7, 8 and improvement in endothelial function.7, 9 We have previously reported that twelve week administration of an ETA receptor antagonist in a porcine hypercholesterolemia model improved coronary endothelial function.10 Atrasentan (Abbott Laboratory, ABT-627, A-147627; trace name Xinlay), an orally available, potent and highly selective antagonist of the ETA receptor11 has been extensively tested in cancer therapy and its effects have been reported in several phase III trials of refractory malignanicies.12, 13 We have recently demonstrated the systemic effects and the safety of long term administration of Atrasentan in humans.14 The effect of long term therapy with an ETA receptor antagonist on the human coronary circulation is unknown. Thus, the current study was designed to extend our previous observations and to test the hypothesis that long term administration of an ETA receptor antagonist improves coronary endothelial function in patients with early coronary atherosclerosis. Moreover, we evaluated the impact of therapy on coronary nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability.

Methods

Study Design

This study is a single center, double blind, randomized control trial, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. The study protocol was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

Subjects were enrolled between July 2001 and December 2006 from those referred to the cardiac catheterization laboratory for evaluation of coronary artery disease, found to have non-obstructive disease, and had comprehensive coronary physiology study including the assessment of endothelial function and non-endothelium-independent coronary flow reserve. Patients were included in this study if they had coronary microvascular endothelial dysfunction. According to our previous studies, we defined microvascular endothelial dysfunction as ≤ 50% increase in coronary blood flow (CBF) in response to the maximal dose of acetylcholine (ACh) compared with baseline CBF.15 Exclusion criteria for the study have been previously reported.15

Study Protocol

At baseline, diagnostic coronary angiography and determination of endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent flow reserve were performed as previously described.15 A Doppler guide wire (0.014-in diameter, FloWire, Volcano Incorporated) within a 2.2F coronary infusion catheter (Ultrafuse, SciMed Life System) was advanced and positioned in the middle portion of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD). Intracoronary bolus injections of incremental doses (18 to 36 μg) of adenosine (Fujisawa), an endothelium-independent vasodilator (primarily of the microcirculation),16 were administered into the guiding catheter until maximal hyperemia was achieved.

Assessment of the endothelium-dependent coronary flow reserve was performed by selective infusion of ACh into the LAD. ACh (Iolab Pharmaceuticals) 10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 mol/L, was infused at 1 mL/min for 3 minutes.3, 15 Hemodynamic data (heart rate and mean arterial pressure), Doppler measurements, and coronary angiography were obtained after each infusion. Endothelium-independent epicardial vasodilation was assessed with an intracoronary bolus injection of nitroglycerin (200 μg, Abbott Laboratories).17

Assessment of Tonic Basal NO Release

In a subset of patients whose consent was obtained prior to the baseline comprehensive coronary physiology study (some patient were consented after their initial cardiac catheterization and did not have this part of the study done), intracoronary NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (L-NMMA), a specific inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis, was infused at a rate of 32 μmol/min for 5 minutes and then at 64 μmol/min for another 5 minutes. Basal NO activity was evaluated by measuring the effect of L-NMMA on % Δ coronary artery diameter and % Δ CBF.

Quantitative Coronary Angiography

Coronary artery diameter (coronary artery diameter) was analyzed from digital images with use of a modification of a previously described technique from this institution.15 The left anterior descending coronary artery was divided into proximal, middle, and distal segments. For each segment, the measurements were performed in the region where the greatest change had occurred during the acetylcholine infusion. An angiographically smooth segment of the proximal, middle, and distal left anterior descending coronary arteries, free of any overlapping branch vessels, was identified in each patient and served as the reference diameter for calculation of diameter stenosis. End-diastolic cine frames that best showed the segment were selected, and calibration of the video and cine images was done, identifying the diameter of the guide catheter. Quantitative measurements of the coronary arteries were obtained using a computer-based image analysis system. Segment diameters were determined at baseline and after both acetylcholine and nitroglycerin administration. The proximal segment was not exposed to Ach and thus served a control segment.

Assessment of Coronary Blood Flow

Doppler flow velocity spectra were analyzed online to determine the time-averaged peak velocity. Volumetric CBF was determined from the following relation: CBF=cross-sectional area × average peak velocity × 0.5.18 Endothelium-dependent coronary flow reserve was calculated as % Δ CBF in response to ACh as previously described19. The endothelium-independent coronary flow reserve ratio was calculated by dividing the average peak velocity after adenosine injection by the baseline average peak velocity.15 Coronary vascular resistance (CVR) was estimated as mean arterial blood pressure/CBF.20

Follow-Up

The patients were randomly assigned and treated in a double-blind fashion according to a computer-generated code with either the ETA receptor antagonist Atrasentan at the dose of 10 mg PO once a day or placebo for six months, in addition to standard medical therapy. Treatment assignments were concealed from participants and study staff except for the pharmacist technician. Study and placebo tablets (provided by Abbott Laboratory) were distributed in bottles and were identical in appearance.

Six month follow-up coronary artery angiogram with coronary physiology study was performed by an independent investigator blinded to treatment allocation. The pre-specified primary endpoint was the change at six months from baseline of % Δ CBF measured by intracoronary graded administration of ACh and % Δ CAD measured by quantitative coronary angiography.

Statistical Analysis

Power calculation

Based on our previous studies21, and assuming a power of 80% and an alpha error=0.05, we calculated the magnitude difference that could be detected for the % Δ coronary artery diameter to ACh 10−4 as 3.9% and % Δ CBF to ACh 10−4 as 37.3% for a sample size of 70 (35 in each group). With the above magnitude difference and given the observed placebo mean from our previous studies of −25.9% for % Δ coronary artery diameter to ACh 10−4 we would expect a significant result if the treatment mean is greater than −22.0%. Similarly given an observed placebo mean of 6.0% for % Δ CBF to ACh 10−4 from our previous studies we would expect a significant result if the treatment mean is greater than 43.3%.

Data are displayed as means ± SD or count and percentage as appropriate. Variables with heavily skewed distribution are reported as medians with first and third quartiles in parenthesis. Analysis to compare different demographic and baseline clinical data between the randomized groups was performed using the Student's t test for continuous data and the Pearson's chi-squared test for categorical data. Baseline data for the CBF, CFR and coronary artery diameter was compared using a rank sum test. Differences between the groups in the primary end points were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Multiple linear regression was used to estimate the treatment effect adjusted for other covariates. All statistical tests were two-sided and a P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the patients

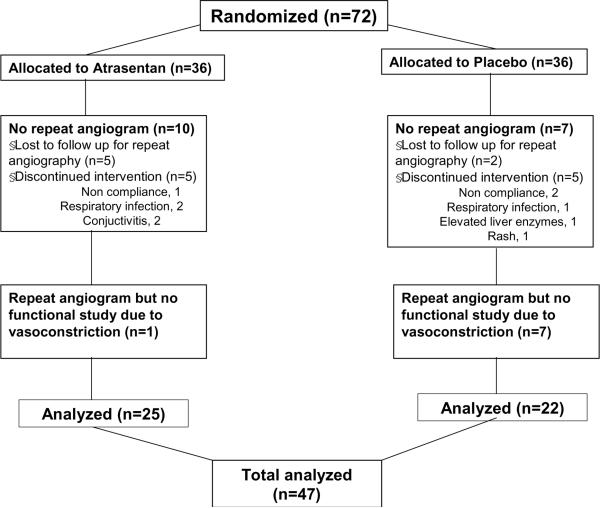

Of the seventy two patients randomized, forty seven had repeated coronary artery angiogram with coronary physiology study at six months and were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the 47 subjects were similar between the Atrasentan and the placebo group (Table 1). Briefly the groups were well matched at baseline with regard to age, gender, race, coronary risk factors and medical treatment.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of random assignment to treatment, completion of the trial, and reasons for not completing it.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | Atrasentan (n=25) | Placebo |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD, y | 49.6 ± 9.1 | 47.8 ± 10.4 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 15 (40) | 12 (55) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2 (8) | 4 (18) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 15 (60) | 12 (57) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 4 (16) | 0 (0) |

| Previous smoker, n (%) | 11 (44) | 9 (41) |

| Family history, n (%) | 18 (72) | 13 (59) |

| Obese (body mass index ≥ 30), n (%) | 13 (52) | 10 (45) |

| LVEF, mean±SD | 63 ± 7 | 67 ± 5 |

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 9 (36) | 5 (23) |

| Antiarrhythmics, n (%) | 5 (20) | 2 (9) |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 9 (36) | 5 (23) |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 14 (56) | 11 (50) |

| Calcium channels blocker, n (%) | 9 (36) | 10 (45) |

| Statin, n (%) | 12 (48) | 9 (41) |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 3 (12) | 5 (23) |

| Oral hypoglycemic, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (14) |

| Insulin, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hemoglobin g/dL, mean±SD | 13.8 ± 1.3 | 19.9 ± 1.4 |

| Glucose mg/dL, mean±SD | 96.6 ± 12.8 | 101.1 ± 24.7 |

| Glycosylated hb %, mean±SD | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 1.1 |

| Insulin level u IU/mL, mean±SD | 11.71 ± 26.5 | 7.7 ± 6.7 |

| Uric acid mg/dL, mean±SD | 6.6 ± 6.2 | 5.2 ± 1.4 |

| Creatinine mg/dL, mean±SD | 1.02 ± 0.16 | 1.02 ± 0.16 |

| Total Cholesterol mg/dL, mean±SD | 189.8 ± 34.8 | 192.8 ± 44.9 |

| Triglycerides mg/dL, mean±SD | 201.4 ± 233 | 140.2 ± 60.4 |

| HDL mg/dL, mean±SD | 46.12 ± 14.1 | 51.2 ± 14.4 |

| LDL mg/dL, mean±SD | 112.1 ± 36.3 | 114.5 ± 40.4 |

| Lipoprotein A mg/dL, mean±SD | 23.0 ± 28.5 | 21.9 ± 26.2 |

Plus-minus values are means ± SD. LVEF indicates left ventricle ejection fraction, HDL- High density lipoprotein, LDL- Low density

The baseline characteristics of the entire cohort have been reported previously14. The patients who had a follow-up coronary physiology study did not differ significantly from those who did not have a follow-up study. Patients who had a follow-up coronary physiology study however had a higher use of calcium channel blockers and diuretics compared at baseline compared to those who did not have a follow-up physiology study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Completers vs. Non completers

| Characteristics | Completers (n=47) | Non Completers (n=25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD, y | 48.7 ± 9.6 | 48.8 ± 11.6 | 0.98 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 20 (43) | 10 (48) | 0.69 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 6 (13) | 2 (9) | 0.7 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 27 (57) | 16 (76) | 0.3 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 4 (9) | 4 (19) | 0.21 |

| Previous smoker, n (%) | 20 (42) | 10 (47) | 0.7 |

| Family history, n (%) | 31 (66) | 15 (71) | 0.69 |

| Obese (body mass index ≥30), n (%) | 23 (49) | 6 (29) | 0.12 |

| LVEF, mean±SD | 66 + 6 | 56 | - |

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 14 (30) | 8 (38) | 0.5 |

| Antiarrhythmics, n (%) | 7 (15) | 3 (14) | 0.95 |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 15 (32) | 5 (24) | 0.5 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 25 (53) | 16 (76) | 0.07 |

| Calcium channels blocker, n (%) | 19 (40) | 17 (81) | 0.002 |

| Statin, n (%) | 21 (45) | 14 (67) | 0.09 |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 8 (17) | 0 (0) | 0.04 |

| Oral hypoglycemic, n (%) | 3 (6) | 1 (5) | 0.79 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0.8 |

LVEF indicates left ventricle ejection fraction

Blood pressure and Heart rate

The baseline heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were similar between the two groups. Long term administration of Atrasentan resulted in a reduction in diastolic blood pressure from 74±3 to 59 ± 17 mmHg (P =0.02) and mean arterial pressure from 94±12 to 86±12 mmHg (P=0.004) but reduction in systolic blood pressure from 120 ±36 to 113 ± 27 mm Hg was not significant (P=0.96). Systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressures did not change in the placebo group. There was no effect in heart rate (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline and Follow-Up of outcome measures.

| Variable | Atrasentan | Placebo | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic Blood Pressure | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 120 ± 36 | 124 ± 18 | 0.2 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 113 ± 27 | 126 ± 14 | 0.07 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | −5 (−29,5) | 3.5 (−19.75,19) | 0.27 |

|

| |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 74 ± 3 | 76 ± 8 | 0.58 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 59 ± 17 | 75 ± 11.5 | 0.002 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | −15 (−22,−2) | 2.5 (−16.5,9.5) | 0.062 |

|

| |||

| Mean Arterial Pressure | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 94 ± 12 | 97 ± 18 | 0.43 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 86 ± 12 | 96 ± 12 | 0.004 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | −11 (−17,−1) | −1 (−8.5,5) | 0.024 |

|

| |||

| Heart Rate | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 68 ± 9 | 73 ± 14 | 0.1 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 71 ± 8 | 75 ± 11 | 0.1 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | 4 (−5,10) | 2.5 (−2,9.25) | 0.97 |

|

| |||

| Coronary Blood Flow, ml/min | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | 48.67 (30.57, 73.89) | 44.15 (30.55, 69.91) | 0.65 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | 59.51 (46.13, 89.63) | 51.08 (43.03, 68.06) | 0.24 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | 15.26 (−7.08, 39.50) | 5.56 (−23.50, 19.0) | 0.25 |

|

| |||

| Coronary Artery Diameter, mm | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | 2.1 (1.95, 2.68) | 2.2 (1.76, 2.5) | 0.45 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | 2.39 (2.03, 2.6) | 2.3 (2, 2.9) | 0.85 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | 0.2 (−0.5, 0.55) | 0.005 (−0.37, 0.53) | 0.62 |

|

| |||

| Coronary vascular resistance mmHg ml-1 | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | 1.83 (1.36, 3.23) | 2.11 (1.49, 3.27) | 0.5 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | 1.47 (1.06, 1.88) | 1.60 (1.45, 2.21) | 0.04 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | −0.55 (−1.32, −0.15) | −0.31 (1.23, 0.58) | 0.5 |

|

| |||

| % Change in coronary blood flow (Ach) | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | −11.32 (−46.06, 13) | 4.81 (−44.22, 37.70) | 0.25 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | 38.21 (2.76, 62.47) | -6.35 (-30.36, 11.53) | 0.003 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | 39.67 (23.24, 68.22) | −2.2 (−27.37, 15.28) | 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| % Change coronary artery diameter (Ach) | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | −33.33 (−41.94, −16.30) | −21.36 (−31.64, −13.45) | 0.07 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | −34.78 (−48.33,−3.77) | −16.67 (−33.39, −6.51) | 0.26 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | 1.07 (−10.40, 20.56) | 8.05 (−17.5, 19.24) | 0.6 |

|

| |||

| % Change coronary flow reserve (Adenosine) | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | 2.9 (2.55, 3.2) | 3.0 (2.68, 3.82) | 0.51 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | 2.6 (2.2, 2.85) | 2.8 (2.4, 3.42) | 0.04 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | −0.3 (−0.55, 0) | −0.25 (−0.63, 0.1) | 0.65 |

|

| |||

| % Change coronary artery diameter (Ntg) | n=25 | n=22 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | 10 (0.75 17.52) | 11.56 (2.78, 22.14) | 0.59 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | 11.43 (6.57, 30.29) | 16.33 (6.55, 23.62) | 0.76 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | 3.33 (−8.0, 20.58) | 9.16 (−7.81, 14.92) | 0.99 |

|

| |||

| % Change coronary blood flow to 64mcg L-NMMA | n=15 | n=15 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | −23.47 (−44.20, −18.42) | −17.14 (−41.56, −2) | 0.31 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | −20.74 (−34.69, −0.91) | −31.14 (−43.91, −23.05) | 0.17 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | −1.28 (−12.83, 28.52) | −11.53 (−33.87, 14.58) | 0.09 |

|

| |||

| % Change coronary artery diameterto 64mcg L-NMMA | n=15 | n=15 | |

| Baseline, median (IQR) | −13.16 (−22.73, −9.68) | −4.57 (−10.82, 0) | 0.03 |

| 6 months, median (IQR) | −13.79 (−17.39, 0) | −13.33 (−17.22, −5.36) | 0.98 |

| Difference, median (IQR) | 3.52 (−8.93, 15.71) | −2.43 (−19.19, 9.04) | 0.19 |

Effect of Atrasentan on Resting Coronary Vascular tone

There was no difference in the resting coronary artery diameter or CBF between the groups at baseline and at six months (Table 3)

Effect of Atrasentan on Coronary Vascular resistance

Long term administration of Atrasentan decreased the CVR though it did not reach statistical significance (P=0.08). CVR at six months was lower in the Atrasentan group compared to placebo (P=0.04). The difference in CVR from baseline to 6 months between the Atrasentan and the placebo group was however not significant (P=0.5; Table 3).

Endothelium-Dependent and Independent Coronary Vascular Function Effect of Atrasentan on the Epicardial circulation

Analysis of % Δ coronary artery diameter to ACh in the middle and distal segments of the LAD produced similar results and we reported only the results of the middle segment. Epicardial response to ACh did not improve after long term administration of Atrasentan (Figure 2). The percent change in coronary epicardial diameter in response to ACh at six months was similar between the Atrasentan group and placebo (P=0.26; Table 3)

Figure 2.

Difference in the mean percent change in Coronary Blood Flow and Coronary Artery Diameter in response to acetylcholine at six months from baseline for Atrasentan and placebo groups

Effect of Atrasentan on Coronary microvascular endothelial function

Long term administration of Atrasentan resulted in significant improvement of coronary microvascular endothelial function (Figure 2). Compared to placebo, 6-month therapy with Atrasentan resulted in a significant improvement in % Δ CBF in response to ACh (P=0.003). There was also a significant difference in improvement in % Δ CBF between the Atrasentan and the placebo group at six months compared to baseline (P<0.001; Table 3). In adjusted analysis using a linear regression model, Atrasentan compared to placebo significantly predicted improvement in coronary microvascular endothelial function even after adjusting for mean arterial pressure, glucose, triglycerides, lipoprotein A and uric acid (adjusted difference in the mean % Δ CBF =.29.86 P<0.001).

Effect of Atrasentan on Coronary endothelium independent function

Endothelium independent CFR to Adenosine was lower with Atrasentan (P=0.01). CFR in the placebo group also decreased though it did not reach statistical significance (P=0.06). Intracoronary administration of adenosine produced a lower CFR in the Atrasentan group at six months compared to placebo (P=0.04). There was however no significant difference in the change in CFR from baseline to 6 months between the Atrasentan and placebo group (P=0.64; Table 3)

Effect of Atrasentan in Response to Intracoronary Nitroglycerin

There was no difference in the % Δ coronary artery diameter after administration of intracoronary Nitroglycerin between the groups at baseline and at six months (Table 3).

Effect of L-NMMA

A total of 30 patients (15 in each group) had L-NMMA administered at baseline and at six months. Effect of L-NMMA on % Δ coronary artery diameter and % Δ CBF was similar between the Atrasentan and placebo group at baseline and after six months of treatment (Table 3) indicating similar blockade of tonic basal release of NO from the coronary circulation in both the groups. The baseline characteristics of the patients who received the L-NMMA study were similar to the patients who did not suggesting that they may be representative of the whole cohort.

Effect of Atrasentan on renal function and metabolic characteristics

Triglyceride level (P=0.013), Lipoprotein-A (P=0.046), uric acid (P=0.006), fasting blood glucose (P=0.026) and glycosylated hemoglobin (P=0.041) improved at six months in the Atrasentan-treated patients as compared with placebo-treated patients. Comparison of the difference at six months from baseline between the Atrasentan-treated patients and placebo treated patient was however significant only for fasting glucose (P=0.02). No significant difference in changes at six months of the creatinine level (P=0.25) or estimated creatinine clearance (P=0.09) was demonstrated between the groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Baseline and follow-up metabolic characteristics

| Variable | Atrasentan (n=31) | Placebo (n=34) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine, mg/dl | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 1 ± 0.15 | 1.02 ± 0.14 | 0.56 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 0.90 ± 0.12 | 0.96 ± 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Difference, mean (SD) | −0.1 ± 0.13 | 0.06 ± 0.14 | 0.254 |

|

| |||

| Creatinine clearance ml/min | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 58 ± 16 | 58 ± 17 | 0.83 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 62 ± 14 | 60 ± 15 | 0.09 |

| Difference, mean (SD) | 4 ± 15 | 2 ± 16 | 0.6 |

|

| |||

| Uric acid, mg/dl | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 4.9 ± 1.16 | 4.9 ± 1.14 | 0.95 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 4.8±1.6 | 5.1±1.3 | 0.048 |

| Difference, mean (SD) | −0.1 ± 1.43 | 0.2 ± 1.23 | 0.08 |

|

| |||

| Glucose, mg/dl | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 96.1 ± 18.3 | 96.0 ± 23.0 | 0.99 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 93.0 ± 14.6 | 104.5 ± 32.0 | 0.026 |

| Difference, mean (SD) | 3.1 ± 5.3 | 8.5 ± 28.6 | 0.02 |

|

| |||

| Glycosylated hb, % | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 0.71 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 5.4 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 0.041 |

| Difference, mean (SD) | 0.1 ± 0.75 | 0.1 ± 0.81 | 0.3 |

|

| |||

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 181.7 ± 202.5 | 127.9 ± 56.0 | 0.14 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 126.0 ± 137.2 | 133.4 ± 75.2 | 0.013 |

| Difference, mean (SD) | −55.7 ± 179 | 5.5 ± 67.7 | 0.07 |

|

| |||

| Lipoprotein A, mg/dl | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 25.5 ± 26.9 | 25.0 ± 28.9 | 0.82 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 18.4 ± 20.5 | 27.9 ± 42.9 | 0.046 |

| Difference, mean (SD) | −7.1 ± 1.45 | 2.9 ± 1.75 | 0.2 |

|

| |||

| Weight, kg | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 86.9 ± 21.3 | 88.6 ± 16.1 | 0.71 |

| 6 months, mean (SD) | 87.6 ± 20.9 | 87.0 ± 27.7 | 0.6 |

| Difference, mean (SD) | 0.7 ± 21.1 | −1.6 ± 1.75 | 0.68 |

Data show the ANOVA test with treatment group as the factor and baseline values as the covariate

Data are mean (SD)

Adverse Effects

The incidence of reported adverse effects was similar between the treatment groups (Table 5). The most common adverse effect with Atrasentan was nasal stuffiness, which occurred in the first week after initiation and persisted during the study period. Headache occurred with a higher incidence in the patients receiving Atrasentan in the first month but was reported at the same rate in the both groups on further follow-up. Edema (upper extremities and facial) occurred more frequently with the initiation of Atrasentan, but after 2 months of follow-up there were no differences between the groups.

Table 5.

Symptoms and Adverse Effects

| Variable | Atrasentan | Placebo | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects, n | 32 | 27 | 0.067 |

| Headache, n | 25 | 20 | 0.18 |

| Nasal Stuffiness, n | 30 | 19 | <0.001 |

| Edema | |||

| Lower extremities, n | 24 | 20 | 0.3 |

| Upper extremities, n | 19 | 11 | 0.034 |

| Facial, n | 18 | 5 | <0.001 |

| Shortness of breath, n | 27 | 23 | 0.25 |

| Fatigue, n | 27 | 27 | 0.78 |

| Vertigo, n | 19 | 22 | 0.54 |

| Lightheadedness, n | 24 | 22 | 0.46 |

| Flushing, n | 19 | 14 | 0.17 |

| Insominia, n | 19 | 16 | 0.37 |

| Withdraw, n | 4 | 2 | 0.65 |

| Time to withdraw, range, d | 56±55 | 67±66 | 0.74 |

| Hospitalizations | |||

| Hospitalizations, n | 19 | 21 | 0.62 |

| Reason for hospitalizations | |||

| Chest pain, n | 17 | 21 | 0.13 |

| Atrial fibrilation, n | 2 | 0 |

There were no changes in body weight in the patients treated with Atrasentan. There were no changes in levels of sodium or albumin in the Atrasentan group. No patient developed proteinuria or hematuria during the study period.

A mild drop in hemoglobin concentration was observed within the first month of treatment but remained stable within the subsequent 5 months. In the Atrasentan group, the reductions of mean hemoglobin at the end of the treatment were 1.18±1.17 g/dL as compared with 0.63±0.90 g/dL in the placebo group (P=0.04). However, no patient required blood transfusion during the study period. No significant changes were observed in white blood count or platelet count in the Atrasentan-treated patients. There were no increases and no clinically significant changes in liver enzymes.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that long term ETA receptor antagonism improves coronary microvascular endothelial function in patients with early atherosclerosis and non obstructive coronary artery disease. ET-1 mediated ETA receptor activation however did not have any significant effect on resting coronary vascular tone or epicardial endothelial function. We have also previously shown improvement of systemic hemodynamic and metabolic profile with long term ETA receptor antagonism in humans14. The current study serves as a natural extension of this study and supports a role for ET-1 in the regulation of coronary endothelial function in humans.

Effect of ETA Receptor Blockade on Coronary Vascular Tone

The present study did not show significant contribution of ET-1 mediated ETA receptor activation to either the basal epicardial or microcirculatory coronary vasoconstrictor tone. Previous studies have demonstrated that acute blockade of ETA receptors resulted in dilatation of coronary epicardial arterie.7, 8 The effects on the coronary microcirculation was however much less pronounced9, with some studies showing no change in coronary blood flow velocity after acute ETA receptor blockade.22 In one study, the vasodilation by ETA receptor antagonism was greater in atherosclerotic coronary arteries compared to normal coronary arteries22 reflecting the relative increase in vascular tissue and circulating ET-1 concentrations in atherosclerotic plaques.2, 23, 24 Thus, the endogenous ET-1 pathway may play a more significant role in regulation of vascular tone in pathophysiological states associated with more advanced atherosclerotic plaques.2, 15 Therefore, the lack of the effect of ETA receptor antagonism on basal coronary vascular tone in the current study may be related to the fact that the patient population did not have significant coronary atherosclerosis.

Effects of ETA receptor Blockade on Microcirculatory Coronary Endothelial Function

Short term ETA receptor antagonism causes improvement in the microcirculatory coronary endothelial function.7, 9 One study showed an improvement in coronary microcirculation function in response to ACh infusion with the greatest impairment of endothelial function deriving the greatest improvement after acute ETA blockade9. Recent studies have also shown that ETA receptor activation contributes to peripheral endothelial dysfunction25. Thus, our current study is in accord with these clinical observations and demonstrates for the first time the beneficial effects of long term administration of ETA receptor antagonist on microcirculation coronary endothelial function.

In the current study long term ETA antagonism did not affect epicardial vessel endothelium-dependent or independent function. Previous studies with acute ETA antagonism showed improvement in epicardial coronary endothelial function only in those segments that constricted in response to ACh administration.9 Our study cohort included both coronary vessels that constricted and those that dilated with ACH likely attenuating the vasodilatory effect of Atrasentan on the epicardial vessels.

Effect of ETA receptor blockade on Coronary endothelium independent function

Long term ETA receptor antagonism decreased endothelium independent CFR in response to adenosine. Coronary flow reserve is calculated as the ratio between hyperemic blood flow and resting coronary blood flow. The reduction in CFR to adenosine may thus reflect the relatively small increase in resting coronary blood flow (although not significant) or a reduction in coronary vascular resistance to long term ETA receptor blockade.

Potential Mechanisms

Long term ETA receptor antagonism may improve coronary microvascular endothelial function through several potential mechanisms including direct effects on the vasoconstriction caused by ET-1 activity, decrease in oxidative stress and inflammation, improvement in metabolic characteristics, attenuation of atherosclerosis and augmentation of nitric oxide pathways.

Direct effect on Vasoconstriction activity of ET-1

The sustained and potent vasoconstrictive response of ET-1 is mediated primarily through activation of ETA receptors24 which are the predominant receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells. In this study and in previous studies of acute inhibition of ETA receptor in experimental porcine hypercholesterolemia26 we did not show any attenuation in ACh-induced epicardial vasoconstriction. We previously reported the beneficial effects of Atrasentan in lowering blood pressure observed in this study.14 Other clinical trials have also shown similar beneficial effects of ETA receptor blockade on systemic blood pressure.27 The improvement in blood pressure observed in this study may have accounted for some of the improvement in the endothelial vasodilator function. However in the adjusted analysis, the improvement in microvascular endothelial function occurred even after adjusting for the hemodynamic and metabolic effects of Atrasentan. This suggests that attenuation of the vasoconstricting effect is not the only mechanism of improving endothelial function.

ET-1 and NO

Classically endothelial dysfunction has been considered to be the result of a decrease in NO bioavailability.3 Deficiency of the endothelium-derived NO is well documented in coronary endothelial dysfunction28, 29 and in human atherosclerotic arteries.24 ET-1 can decrease NO bioavailability by decreasing it production via inhibition of eNOS activity or by increasing it degradation via formation of oxygen radicals.30, 31 ET-1 also functionally offsets the vasodilator action of NO, and thereby participates in regulation of vascular tone.

Similar response to L-NMMA in the Atrasentan and placebo groups in this study implies that the effect on basal NO production by ETA receptor blockade is also not the main mechanism in the improvement of microvascular endothelial function in patients with early atherosclerosis. Thus, the interaction between ET-1 and NO may involve the degradation of NO. We have previously demonstrated the association between oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in animal models.29 32 Diet induced hypercholesterolemia in porcine experimental models resulted in blunted endothelial function in the renal circulation29 as well as in the coronary circulation32 and these were restored by antioxidant interventions. We have also recently shown that that coronary endothelial dysfunction in humans is characterized by local enhancement of oxidative stress.33 Both ETA and ETB receptors can increase ROS production34, 35 which reacts with NO to produce peroxynitrite. ETA receptor blockade may lead to reduced production of ROS and decreased NO degradation leading to improvement in NO dependent vasorelaxation.

Attenuation of Atherosclerosis

ET-1 is increased in patients with atherosclerotic risk factors such hypertension diabetes and smoking. It is also elevated locally in atherosclerotic plaques23, 24 and the circulation and vascular tissue levels correlate with severity of atherosclerotic lesions.2, 36 One of the mechanisms by which long term ETA receptor antagonism improved coronary microcirculatory endothelial function may be by the reduction in risk factors that may contribute to endothelial dysfunction. We have reported that long term treatment with Atrasentan resulted in a reduction of blood pressure, improvement in glucose and lipid metabolism as well as improvement in renal function in a subset of patients not treated with ACE inhibitors.14 Thus, the beneficial effect of the blockade of the endogenous ET-1 pathway in the current study may be in part mediated by the reduction in blood pressure and improvement in lipid and glucose metabolism. By modifying atherosclerotic risk factors and attenuating the atherosclerotic process it may be speculated that long term ETA receptor antagonists may attenuate the progression of atherosclerosis by reversing endothelial dysfunction.

Limitations

There are several limitation to this study. First, a significant number of patients did not have a follow up coronary physiology study. Among these patients, some did not have a repeat angiogram and the rest had a repeat angiogram but developed coronary artery vasoconstriction that precluded the endothelial function study. The baseline characteristics of the patients who had a follow-up coronary physiology study however did not differ significantly from those who did not. The rate of adverse effects were also similar between the two groups. Even with these measures there still remains a risk of bias in the results.

Second, the number of subjects having repeat coronary physiology studies was lower than expected and this may have reduced the power to find significant differences in some of the endpoints.

Third, we did not perform an intent-to-treat analysis in our primary outcome as we did not have follow-up coronary physiology study data on a significant number of patients. Fourth, the small sample size means that overfitting is a concern in the case of multiple regression modeling and may cause instability in model estimates. Overfitting is especially a concern when one is creating a prediction model with the intention of applying it to external data sets. In our case the model was not aimed at predicting future outcomes, but for controlling other factors in estimating the size of the Atrasentan effect. Still, overfitting could result in instability of the effect estimate. We did not find this to be the case, however, as the adjusted Atrasentan estimate was nearly the same as the unadjusted estimate, and the standard error was not so large as to render the hypothesis test non-significant. Thus we are confident that our conclusions with regards to Atrasentan are valid.

Fifth, the present study was not designed to explain the precise cellular mechanism of the effects of long term administration of Atrasentan on coronary physiology. Due to lack of standardization in measurements of invasive endothelial function we are limited in our ability compare the observed effects with those from studies measuring more acute effects of Atrasentan. The measured effects on coronary physiology may indeed reflect the acute effect from the last given dose(s). More studies are thus needed to elucidate the mechanisms of long term ETA receptor antagonism in improving coronary microvascular endothelial function. Six we do not have data on the degree of atherosclerosis in the patients through intra vascular ultrasound. We thus cannot correlate the improvement in endothelial function observed with the degree of atherosclerosis.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that six month treatment with Atrasentan improves coronary microvascular endothelial function. It emphasizes the importance of ET-1 on the cardiovascular system and the potential of long term ETA receptor antagonism to improve endothelial dysfunction.

This study demonstrates for the first time that the endogenous ET-1 plays a role in long term coronary microvascular endothelial function and in the pathogenesis and progression of coronary endothelial dysfunction a known prognostic factor for cardiovascular disease. The current study suggests a potential role for long term ETA receptor antagonists as a therapeutic option for patients with coronary endothelial dysfunction and non-obstructive coronary artery disease.

Clinical Perspective.

Endothelial dysfunction is considered critical in the initiation, progression and complications of coronary artery disease and is independently associated with cardiovascular (CV) events. It is a reversible process that represents the functional expression of an individual's overall CV risk factor burden and many therapies that restore endothelial function also lower CV events. Coronary endothelial function is regulated by the balance of endothelium derived vasodilator and vasoconstrictor factors such as ET-1. This study provides evidence that long term ETA receptor antagonists improves coronary microvascular endothelial function in humans and support a role for the endogenous ET in the mechanism and potentially the treatment of coronary endothelial function in humans.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding The study was supported by grants from the NIH: NIH K24 HL-69840, NIH R01 HL-63911, HL-77131, HL 92954, HL 085307, DK 73608, DK 77013 and Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: Clinical trials.gov identifier NCT00271492 URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov

Disclosures None

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mathew V, Hasdai D, Lerman A. The role of endothelin in coronary atherosclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;7:769–777. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)64842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lerman A, Edwards BS, Hallett JW, Heublein DM, Sandberg SM, Burnett JC., Jr. Circulating and tissue endothelin immunoreactivity in advanced atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:997–1001. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110033251404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerman A, Holmes DR, Jr., Bell MR, Garratt KN, Nishimura RA, Burnett JC., Jr. Endothelin in coronary endothelial dysfunction and early atherosclerosis in humans. Circulation. 1995;92:2426–2431. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.9.2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkles JA, Alberts GF, Brogi E, Libby P. Endothelin-1 and endothelin receptor mRNA expression in normal and atherosclerotic human arteries. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;191:1081–1088. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes WG, Strachan FE, Webb DJ. Endothelin ETA and ETB receptors cause vasoconstriction of human resistance and capacitance vessels in vivo. Circulation. 1995;92:357–363. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhaar MC, Strachan FE, Newby DE, Cruden NL, Koomans HA, Rabelink TJ, Webb DJ. Endothelin-A receptor antagonist-mediated vasodilatation is attenuated by inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis and by endothelin-B receptor blockade. Circulation. 1998;97:752–756. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halcox JP, Nour KR, Zalos G, Quyyumi AA. Endogenous endothelin in human coronary vascular function: differential contribution of endothelin receptor types A and B. Hypertension. 2007;49:1134–1141. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.083303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyriakides ZS, Kremastinos DT, Bofilis E, Tousoulis D, Antoniadis A, Webb DJ. Endogenous endothelin maintains coronary artery tone by endothelin type A receptor stimulation in patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Heart. 2000;84:176–182. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halcox JP, Nour KR, Zalos G, Quyyumi AA. Coronary vasodilation and improvement in endothelial dysfunction with endothelin ET(A) receptor blockade. Circ Res. 2001;89:969–976. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Best PJ, McKenna CJ, Hasdai D, Holmes DR, Jr., Lerman A. Chronic endothelin receptor antagonism preserves coronary endothelial function in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1999;99:1747–1752. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.13.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wessale JL, Adler AL, Novosad EI, Calzadilla SV, Dayton BD, Marsh KC, Winn M, Jae HS, von Geldern TW, Opgenorth TJ, Wu-Wong JR. Pharmacology of endothelin receptor antagonists ABT-627, ABT-546, A-182086 and A-192621: ex vivo and in vivo studies. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103(Suppl 48):112S–117S. doi: 10.1042/CS103S112S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson JB, Love W, Chin JL, Saad F, Schulman CC, Sleep DJ, Qian J, Steinberg J, Carducci M. Phase 3, randomized, controlled trial of Atrasentan in patients with nonmetastatic, hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2478–2487. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carducci MA, Saad F, Abrahamsson PA, Dearnaley DP, Schulman CC, North SA, Sleep DJ, Isaacson JD, Nelson JB. A phase 3 randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of Atrasentan in men with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1959–1966. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raichlin E, Prasad A, Mathew V, Kent B, Holmes DR, Jr., Pumper GM, Nelson RE, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Efficacy and safety of Atrasentan in patients with cardiovascular risk and early atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2008;52:522–528. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasdai D, Gibbons RJ, Holmes DR, Jr., Higano ST, Lerman A. Coronary endothelial dysfunction in humans is associated with myocardial perfusion defects. Circulation. 1997;96:3390–3395. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hori M, Kitakaze M. Adenosine, the heart, and coronary circulation. Hypertension. 1991;18:565–574. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison DG, Bates JN. The nitrovasodilators. New ideas about old drugs. Circulation. 1993;87:1461–1467. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.5.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doucette JW, Corl PD, Payne HM, Flynn AE, Goto M, Nassi M, Segal J. Validation of a Doppler guide wire for intravascular measurement of coronary artery flow velocity. Circulation. 1992;85:1899–1911. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.5.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ofili EO, Labovitz AJ, Kern MJ. Coronary flow velocity dynamics in normal and diseased arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:3D–9D. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90128-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quyyumi AA, Dakak N, Andrews NP, Gilligan DM, Panza JA, Cannon RO., 3rd Contribution of nitric oxide to metabolic coronary vasodilation in the human heart. Circulation. 1995;92:320–326. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerman A, Burnett JC, Jr., Higano ST, McKinley LJ, Holmes DR., Jr. Long-term L-arginine supplementation improves small-vessel coronary endothelial function in humans. Circulation. 1998;97:2123–2128. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinlay S, Behrendt D, Wainstein M, Beltrame J, Fang JC, Creager MA, Selwyn AP, Ganz P. Role of endothelin-1 in the active constriction of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. Circulation. 2001;104:1114–1118. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.095707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerman A, Webster MW, Chesebro JH, Edwards WD, Wei CM, Fuster V, Burnett JC., Jr. Circulating and tissue endothelin immunoreactivity in hypercholesterolemic pigs. Circulation. 1993;88:2923–2928. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeiher AM, Drexler H, Wollschlager H, Just H. Modulation of coronary vasomotor tone in humans. Progressive endothelial dysfunction with different early stages of coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1991;83:391–401. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardillo C, Campia U, Kilcoyne CM, Bryant MB, Panza JA. Improved endothelium-dependent vasodilation after blockade of endothelin receptors in patients with essential hypertension. Circulation. 2002;105:452–456. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasdai D, Best PJ, Cannan CR, Mathew V, Schwartz RS, Holmes DR, Jr., Lerman A. Acute endothelin-receptor inhibition does not attenuate acetylcholine-induced coronary vasoconstriction in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:108–113. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krum H, Viskoper RJ, Lacourciere Y, Budde M, Charlon V. The effect of an endothelin-receptor antagonist, bosentan, on blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Bosentan Hypertension Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:784–790. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803193381202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew V, Cannan CR, Miller VM, Barber DA, Hasdai D, Schwartz RS, Holmes DR, Jr., Lerman A. Enhanced endothelin-mediated coronary vasoconstriction and attenuated basal nitric oxide activity in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1997;96:1930–1936. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chade AR, Krier JD, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Breen JF, McKusick MA, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Comparison of acute and chronic antioxidant interventions in experimental renovascular disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F1079–1086. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00385.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iglarz M, Clozel M. Mechanisms of ET-1-induced endothelial dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:621–628. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31813c6cc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landmesser U, Harrison DG. Oxidant stress as a marker for cardiovascular events: Ox marks the spot. Circulation. 2001;104:2638–2640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez-Porcel M, Lerman LO, Holmes DR, Jr., Richardson D, Napoli C, Lerman A. Chronic antioxidant supplementation attenuates nuclear factor-kappa B activation and preserves endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic pigs. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:1010–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavi S, Yang EH, Prasad A, Mathew V, Barsness GW, Rihal CS, Lerman LO, Lerman A. The interaction between coronary endothelial dysfunction, local oxidative stress, and endogenous nitric oxide in humans. Hypertension. 2008;51:127–133. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duerrschmidt N, Wippich N, Goettsch W, Broemme HJ, Morawietz H. Endothelin-1 induces NAD(P)H oxidase in human endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:713–717. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loomis ED, Sullivan JC, Osmond DA, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Endothelin mediates superoxide production and vasoconstriction through activation of NADPH oxidase and uncoupled nitric-oxide synthase in the rat aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:1058–1064. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossi GP, Colonna S, Pavan E, Albertin G, Della Rocca F, Gerosa G, Casarotto D, Sartore S, Pauletto P, Pessina AC. Endothelin-1 and its mRNA in the wall layers of human arteries ex vivo. Circulation. 1999;99:1147–1155. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]