Abstract

Over a ten-year period, we prospectively evaluated the reasons for revision for contemporary and highly crosslinked polyethylene formulations in a multicenter retrieval program. 212 consecutive retrievals were classified as conventional gamma-inert sterilized liners (n=37), annealed (Crossfire™, n=72), or remelted (Longevity™, XLPE, Durasul; n=93). The most frequent reasons for revision were loosening (35%), instability (28%) and infection (21%) and were not related to polyethylene formulation (p = 0.17). Annealed and remelted liners had comparable linear penetration rates (0.03 and 0.04 mm/y, respectively, on average) and were significantly lower than conventional retrievals (0.11 mm/y; p ≤ 0.0005). This retrieval study including first-generation highly crosslinked liners demonstrated lower wear than conventional polyethylene. While loosening remained the most prevalent reason for revision, we could not demonstrate a relationship between wear and loosening. The long-term clinical performance of first-generation highly crosslinked remains promising, based on the mid-term outcomes of the components documented in this study.

Keywords: Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene, UHMWPE, revision, total hip replacement, total hip arthroplasty, crosslinking, wear

Introduction

Starting in 1998, radiation-crosslinked and thermally treated polyethylenes were clinically introduced to reduce wear and the incidence of revision due to osteolysis [1]. A second motivation for developing these highly crosslinked polyethylenes was to reduce oxidation, which had been associated with short-term clinical failures following gamma sterilization in air and long-term shelf aging in air. One approach, known as annealing, involves a single thermal treatment below the crystalline melt transition in polyethylene to preserve crystallinity and mechanical properties. A second approach to polyethylene formulation, referred to as remelting, involves thermal treatment above the melt transition. To date, generally favorable clinical performance has been reported in studies of annealed and remelted polyethylenes [1].

Revision has rarely been reported in previous longitudinal studies of crosslinked polyethylene due to the relatively small sample sizes employed and their execution in a single-center by experienced surgeons. Consequently, previous radiographic wear studies provide limited insight into the reasons for revision or the mechanisms of clinical failure for crosslinked polyethylene under real world conditions. Bozic and colleagues analyzed revision reasons for total hip arthroplasty in a nationally representative administrative database for the United States [2]. Researchers determined that the most frequently reported causes of clinical failure were instability (22.5%), loosening (19.7%), and infection (14.5%), but wear and osteolysis were reported in only 5.0% and 6.6% of revisions, respectively [2]. However, polyethylene formulation cannot be identified from administrative data, which classify procedures using ICD9-CM codes. Thus, it remains unknown whether the clinical failure modes differ among historical (gamma air), conventional (gamma inert-sterilized), and crosslinked polyethylenes.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the overall clinical performance of gamma-inert (control) and first-generation highly crosslinked liners in terms of the reasons for revision as well as femoral head penetration. We also tested the hypothesis that loosening as a reason for revision of highly crosslinked liners will be lower in prevalence than in conventional gamma inert sterilized liners. To test these hypotheses, we performed a detailed review of the clinical records for a consecutive series of revised hip arthroplasty patients over a ten-year period and combined the clinical data with a detailed retrieval analysis that included measurements of femoral head penetration. A secondary goal of our study was to examine the role of head size on the penetration rate of highly crosslinked liners.

Methods and Materials

Implant Information

212 acetabular liners were consecutively retrieved after revision surgery during a ten-year period by five urban medical centers in collaboration with two implant retrieval centers. Retrievals were classified as annealed (Crossfire™, n=72), remelted group 1 (Longevity™, n=93), remelted group 2 (XLPE, n=7), remelted group 3 (Durasul™; n=3), and conventional, gamma-inert sterilized, liners (n=37). All these materials were fabricated from GUR 1050 polyethylene resin and consolidated either by ram extrusion or compression molding. In the case of highly crosslinked polyethylenes, the starting material was subjected to gamma irradiation (annealed and remelted group 2) or electron beam irradiation (remelted groups 1 and 3) after consolidation. Following the corresponding thermal stabilization treatment, acetabular liners were machined and terminally sterilized by means of gamma irradiation in an inert environment (annealed liners), gas plasma (remelted group 1), or ethylene oxide (remelted groups 2 and 3). In contrast to conventional acetabular liners, which received a radiation dose between 25 and 40 kGy, the total radiation dose absorbed by highly crosslinked polyethylene acetabular liners ranged from 95 to 105 kGy [1]. Patient and clinical data, including implantation times and reasons for revision, were traced in all cases. Explanted liners were cleaned using institutional procedures and expeditiously stored in a subzero freezer (−80 °C) to minimize ex vivo oxidative changes, as described previously [3].

The conventional acetabular liners were produced in two different designs, namely Trilogy (n=34; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN); and Harris-Galante II (n=3; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN). The annealed retrievals were manufactured in three designs: Trident (n=38; Stryker Orthopedics, Mahwah, NJ); Omnifit (n=33; Stryker Orthopedics, Mahwah, NJ); and System 12 (n=1; Stryker Orthopedics, Mahwah, NJ), whereas the remelted retrieval groups 1–3 included a single liner design each: Trilogy (n=93; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN); Reflection (n=7; Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN); and Epsilon (n=3; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN), respectively. The sterilization dates were traceable by manufacturers from the lot codes in 150 (71%) retrieved liners, so that the time elapsed between sterilization and implantation (that is, shelf life) could be computed. The retrieved conventional liners were stored on the shelf for an average of 0.9 years (range: 0.1–3.6 years), whereas annealed and group 1 remelted retrievals were implanted after generally shorter average shelf lives: 0.5y (range: 0.0–3.4y); and 0.9 (range: 0.0–4.1y) respectively. The sterilization dates corresponding to remelted liners in groups 2 and 3 were not available.

Retrieved liners had inner diameters ranging from 22 mm to 40 mm. Among the conventional and crosslinked liners, 11% and 55% had a femoral head of 32 mm or greater, respectively. Specifically, the conventional retrieval group consisted of liners with 22 mm (n=1); 26 mm (n=3); 28 mm (n=29); and 32 mm (n=4) inner diameters. On the other hand, the retrieved annealed liners were produced in three inner sizes, namely 28 mm (n=38); 32 mm (n=26); and 36 mm (n=8), whereas remelted liners from group 1 had inner diameters 28 mm (n=31); 32mm (n=36); 36 mm (n=16); and 40 mm (n=10). Likewise, remelted liners from retrieval group 2 comprised three subsets of liners with 28 mm (n=1); 32 mm (n=4); and 36 mm (n=2) inner diameters, respectively. Finally, remelted liners from group 3 had 32 mm (n=2); and 38 mm (n=1) inner sizes. The outer diameter of the acetabular shells was known in 190 cases (90%) and ranged from 46 to 80 mm.

Overall, the femoral head material could be identified for 209 (99%) of the 212 liners and included cobalt chromium (CoCr) alloy and four types of ceramic surfaces. Among the conventional and crosslinked liners, 8% and 17% had a ceramic surface femoral head material, respectively. Specifically, the retrieved conventional liners articulated against CoCr (n=33); and zirconia ceramic (n=3) femoral heads. Similarly, annealed liners matched CoCr (n=52); zirconia ceramic (n=12); and alumina ceramic (n=8) femoral heads. Most of the remelted group 1 liners articulated against CoCr heads (n=85), and few of them were implanted along with various types of ceramic femoral heads, namely alumina ceramic (n=3); zirconia ceramic (n=1); alumina matrix composite (Biolox Delta, n=1) and unknown ceramic (n=1). The femoral heads employed with remelted group 2 liners were produced from oxidized zirconium (Oxinium, n=4); and CoCr (n=3). The three remelted liners in group 3 had CoCr femoral heads.

Clinical Information

In addition to insertion and removal dates of the retrieved liners, patient details, such as surgical side, sex, age, and weight were evaluated. Patient activity was also assessed in 71% (151/212) of the patients using the UCLA activity scale ranging from 1 to 10 [4]. Patients were asked in a questionnaire to assess their level of activity both at the time of insertion and at the time of the onset of symptoms leading to revision of the polyethylene liner. Implantation times, patient demographics, as well as patient activity levels are summarized in Table 1. Conventional acetabular liners were implanted for significantly longer periods than all the highly crosslinked liners (p ≤ 0.0008; Student’s t-test). Also, retrieved annealed liners were in vivo significantly longer than remelted liners from Group 1 (p=0.01). Regarding patient demographics and level of activity at insertion of the liner, preliminary statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between the five patient cohorts (p ≥ 0.12). In contrast, activity levels at the onset of symptoms were significantly lower for patients who received a remelted 1 HXLPE liner (p=0.01).

Table 1.

Summary of patient characteristics for the retrieved conventional and highly crosslinked polyethylene liners. Statistical analysis (either Wilcoxon test, Student’s t test or contingency analysis as appropriate) confirmed no significant differences between patient cohorts.

| FORMULATION | Primary Surgeries | Patient Gender | Mean Patient Age (Range, y) | Mean Patient Mass (Range, kg) | Patient Body Mass Index (Range kg) | UCLA* Score at insertion, Mean (Range) | UCLA* Score at revision Mean (Range) | Mean Implantation Time (Range, y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional (N=37) | 22 (71 %) | 23 F (62 %) | 61 (32–82) | 82 (50–125) | 29 (16–40) | 5 (1–9) | 4 (1–8) | 6.0 (0.0–13.8) |

| Annealed (N=72) | 42 (60 %) | 38 F (53 %) | 63 (29–81) | 83 (45–148) | 28 (16–46) | 4 (1–10) | 4 (1–10) | 2.9 (0.0–8.0) |

| Remelted Group 1 (N=93) | 47 (56 %) | 54 F (58 %) | 61 (33–89) | 81 (34–141) | 28 (13–44) | 5 (1–9) | 3 (1–8) | 1.9 (0.0–7.3) |

| Remelted Group 2 (N=7) | 2 (29 %) | 4 F (57 %) | 53 (40–77) | 80 (68–95) | 28 (26–34) | 4 (2–6) | 5 (2–10) | 0.9 (0.2–1.9) |

| Remelted Group 3 (N=3) | 1 (33 %) | 1 F (33 %) | 86 (86 – 86) | 98 (98–98) | 26 (26 – 26) | N/A | N/A | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) |

| All Remelted, Groups 1–3 (N=103) | 50 (54 %) | 59 F (57 %) | 61 (33–89) | 81 (34–141) | 28 (13–44) | 4 (1–9) | 3 (1–10) | 1.9 (0.0–9.4) |

UCLA activity score was based on the 1–10 survey reported by Zahiri et al. [4]

Of the 212 patients included in this study, 113 (53%) received the retrieved polyethylene liner at primary surgery, while the rest had a history of previous revisions (Table 1). To document the revision reasons, revision surgery medical records were thoroughly reviewed in all cases in conjunction with radiographs (when available). We paid special attention to those cases in which surgeons reported osteolysis and/or polyethylene wear in the medical records.

Femoral Penetration Measurements

The thickness of the intact liners was measured in both superior (loaded) and inferior (unloaded) regions using a calibrated digital micrometer (accuracy 0.001 mm), as described previously [5, 6]. Since dimensional changes during the 12 months following implantation are a combination of creep and a comparatively lower contribution of wear in conventional and HXLPE inserts [7, 8], femoral penetration rates were obtained only for liners that were in vivo longer than a year. After the first year of implantation, creep decreases substantially, and changes in femoral head penetration are considered primarily due to polyethylene wear. There were a total of 144 liners (33 conventional, 53 annealed, 55 remelted group 1, 2 remelted group 2, and 1 remelted group 3 implants) with implantation times of greater than one year that were amenable to measure using this method.

Statistical Analysis

Student t-tests, or Wilcoxon tests in the case of non-normal distributions, served to assess differences in linear penetration rate between the five retrieval groups. In addition, general linear models with implantation time and other covariates (patient factors, head material, head size, etc.) were used to examine the potential significance of patient and implant factors on femoral head penetration. The level of significance for the entire statistical analysis was p < 0.05.

Preliminary statistical analyses showed no significant difference in the femoral head penetration rates among the remelted liners. Consequently, we pooled the results of the remelted liners for subsequent analyses, which are reported here. Similarly, we were unable to detect significant differences between the various ceramic bearing surfaces examined here, thus we also pooled ceramic bearing surfaces into a single category for comparison with CoCr.

Results

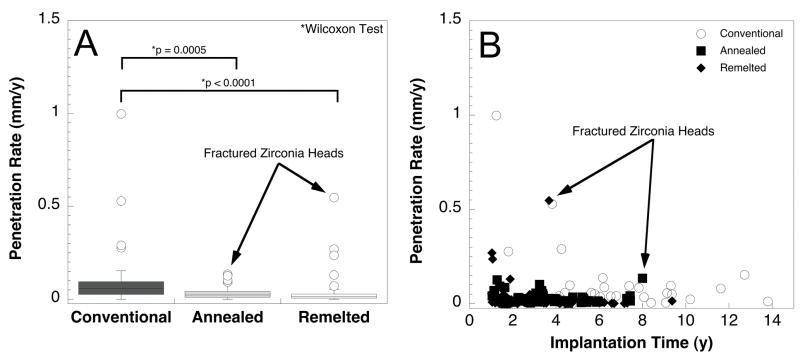

The distribution of primary revision reasons for the retrieved acetabular liners was not related to polyethylene formulation (Pearson test; Chi2 = 70.58; p = 0.17; Figure 1). Overall, among all liners studied, the most frequent clinical failure modes were loosening (n=74/212; 35%), instability (n= 59/212; 28%) and infection (n= 45/212; 21%). Malalignment (n=6; 3%); leg length discrepancy (n=5; 2%); periprosthetic fracture (n=5; 2%); fracture of ceramic head (n=3); hematoma (n=3); impingement (n=3); fibrous ingrowth (n=2); heterotopic ossification (n=2); subluxation (n=2); metallosis (n=1); pain (n=1); and revision of Prostalac antibiotic spacer (n=1) were the remaining revision reasons for the present acetabular liners. Of the 74 cases of loosening, 41 (55%) involved loosening of the acetabular component; 37 (50%) involved loosening of the femoral component; and 4 (5%) involved loosening of both components. The average time (± SD) between implantation and revision for the cases with loosening was 6.9 ± 3.0 years (range: 3.8 to 13.8 years) for the gamma inert group, 3.1 ± 1.8 years (range: 0.3 to 7.4 years) for the annealed group, and 2.9 ± 2.1 years (range: 0.1 to 7.3 years) for the remelted group, respectively. When we excluded re-revisions from the overall cohort, the distribution of the reasons for revisions for patients who received primary acetabular liners at index surgery (n=114) was likewise not influenced by polyethylene formulation (Pearson test; Chi2 = 46.8; p = 0.36). According to logistic models, the incidence of reason for revision was not significantly affected by patient factors, such as gender, weight, or BMI (p ≥ 0.26).

Figure 1.

Distribution of reasons for revision with conventional gamma inert, annealed, and remelted highly crosslinked acetabular liners. There was no significant difference in the distribution of revision reasons among groups (p = 0.17). Other includes: Malalignment (n=6; 3%); leg length discrepancy (n=5; 2%); fracture of ceramic head (n=3); hematoma (n=3); fibrous ingrowth (n=2); heterotopic ossification (n=2); subluxation (n=2); metallosis (n=1); pain (n=1); and revision of Prostalac antibiotic spacer (n=1).

There were 4/212 revisions involving device-related component fractures in this series involving ceramic femoral heads in three cases and one highly crosslinked acetabular liner. The three fractured zirconia femoral heads belonged to batches recalled in 2001 by Desmarquest, as confirmed by lot numbers. In one case of chronic hip instability, the rim of an annealed liner was fractured at the time of revision surgery after 7.3 years of implantation. The patient’s body mass index (BMI) was 41.5 kg/m2 (clinically obese), and according to the UCLA activity level questionnaire, she was moderately active, corresponding to a maximum UCLA score of 6 at any point after index surgery. The liner fracture in this case was limited to the rim and consistent with repetitive impingement leading to crack initiation in one area of the liner rim, which then propagated to material failure. Upon revision, the locking mechanism was found to be intact. After detachment of the rim fragment, the femoral head appears to have shifted superiorly to chronically articulate on the new rim fracture surface.

Among our gamma inert sterilized revisions, 62% were due to loosening, wear, and osteolysis. None of the annealed and crosslinked liners in our study were revised for wear or osteolysis. While not always the reason for revision, osteolysis was documented by the treating surgeon in the operative notes for 50/212 revisions. Excluding patients with a previous history of revisions, osteolysis was noted in the charts for 6/22 (27%) primary patients with conventional retrievals, 8/42 (19%) primary patients with annealed liners, and 11/50 (22%) primary patients with remelted liners.

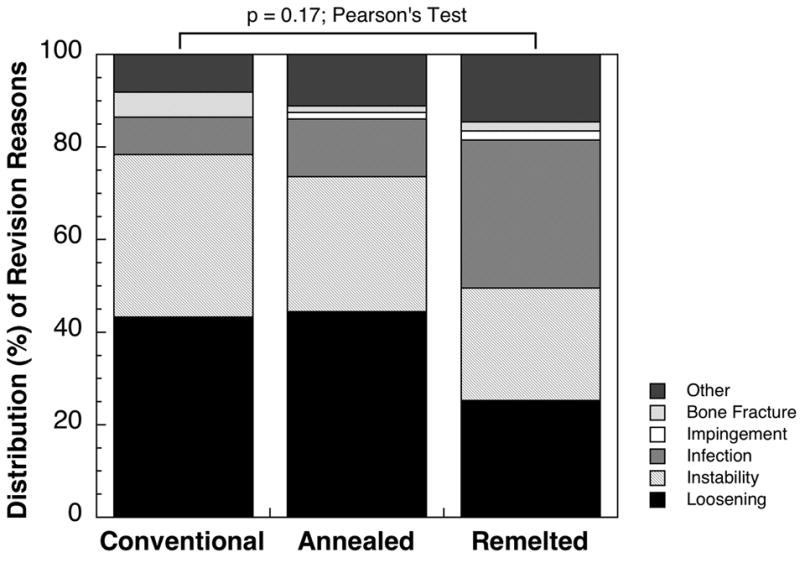

Annealed and remelted liners exhibited comparable linear penetration rates (0.03 and 0.04, respectively, on average; p = 0.01; Wilcoxon test; Power = 7%) and were significantly lower than conventional retrievals (0.11 mm/y; p ≤ 0.0005; Wilcoxon test; Power = 84% and 88% for annealed and remelted liners, respectively; Figure 2A, Table 2). We found no evidence of increasing femoral penetration rates with longer implantation times among retrieved highly crosslinked liners (Figure 2B). Outliers in the remelted group were generally attributed to short implantation time (creep) within 1–2 years of service and/or cases in which a zirconia femoral head fractured (Figure 2B). 36 mm heads resulted in significantly higher femoral penetration than 32 and 28 mm heads for remelted liners (excluding ceramic head fractures; p = 0.0002; Power=98%, Table 2). However, no significant differences were detected between penetration of liners matched with either 28mm or 32mm (p=0.24; Power=22%, Table 2). Our study was insufficiently powered to detect differences in femoral head penetration among annealed highly crosslinked liners as a function of head size (Table 2, p=0.74, Power=9%) or femoral head material within both annealed and remelted formulations (p = 0.08, and 0.4; Power=43% and 13%, respectively). Patient factors, such as age, weight and level of activity likewise had no significant effects on the linear penetration rates for the present retrievals (p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Femoral head penetration for retrieved acetabular liners with an implantation time of greater than 1 year in vivo by liner material (A) and by implantation time (B).

Table 2.

Linear femoral head penetration rates (mean and SD) for retrieved acetabular liners stratified by femoral head size and by polyethylene formulation (conventional, highly crosslinked annealed and/or remelted).

| FORMULATION HEAD SIZE | Conventional | Annealed | Remelted | All Crosslinked Liners (Annealed and Remelted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤28 mm | N=30 (0.09 ± 0.18 mm/y) | N=25 (0.03 ± 0.03 mm/y)* | N=21 (0.01 ± 0.01 mm/y)* | N=46 (0.02 ± 0.02 mm/y)* |

| 32 mm | N=3 (0.27 ± 0.26 mm/y) | N=21 (0.03 ± 0.03 mm/y) | N=26 (0.02 ± 0.01 mm/y) | N=47 (0.02 ±0.02 mm/y) |

| 36 mm | N/A | N=5 (0.04 ± 0.03 mm/y) | N=10 (0.08 ± 0.10 mm/y) | N=15 (0.07 ± 0.08 mm/y) |

| Overall | N=33 (0.11± 0.19 mm/y) | N=51 (0.03 ± 0.03 mm/y)* | N=57 (0.03 ± 0.05 mm/y)* | N=108 (0.03 ± 0.04 mm/y)* |

N/A. Not applicable or not amenable to measure (in vivo time < 1 year or iatrogenic damage)

Fractured zirconia head(s) excluded.

Discussion

This retrieval study documents the clinical failure modes and femoral head penetration for first-generation highly crosslinked polyethylenes within the first decade of service. Previous studies in the mid- to late 1990s involving historical, gamma air sterilized polyethylene implicated particulate wear debris as the main reason for late aseptic loosening [9–11]. Despite the superior wear performance of highly crosslinked liners, aseptic loosening remained the most frequent reason for revision among the contemporary retrievals in our series. Because our assessment of osteolysis was limited to chart review, we were unable to assess the extent or severity of bone loss, or its etiology in this study. Furthermore, we found aseptic loosening with both conventional and highly crosslinked liners to be a “catch all” for a variety of clinical failure modes, including mechanical loosening, pelvic fracture, and protrusio. Many of our retrievals (27/212, 13%) that were revised for loosening had a history of previous revisions.

The lack of specificity in a revision diagnosis for aseptic loosening complicates the comparison of our retrieval study results with previous studies in which a radiographic endpoint following a primary surgery may have been employed. Nevertheless, it is clear from our findings that there are many mechanisms of implant fixation failure in the first decade of implantation that do not appear to be mediated by a more wear resistant bearing material. For example, researchers have recently suggested that early loss of fixation may in some cases be due to subclinical infections [12–14]. We found that 21% of our revisions were due to infection, which was comparable to the findings of Bozic et al. [2], who observed that infection was the third most frequently diagnosed reason for revision in a nationally representative administrative database. Our retrieval findings highlight the importance of further biomechanical and biological research in the prevention of early loosening.

Our head penetration findings for first-generation crosslinked polyethylenes were consistent with previous clinical studies and the expectations from in vitro testing [1]. Because femoral head penetration is a combination of creep (bedding in) and wear, we focused our investigation on retrieved liners with greater than one year of implantation. Using this criterion, we observed significantly lower femoral head penetration for both remelted and annealed highly crosslinked polyethylene compared with the gamma inert control. Because of the variability in penetration data, we were unable to detect a significant difference between remelted and annealed liners (power = 6%). A sample size of 2500 would be necessary to detect a 10% difference in the penetration rates between these two types of retrieved highly crosslinked liners.

Historically, the femoral heads used for polyethylene hip bearings have been 28 mm or less, due to concerns about increased wear with 32 mm or greater head sizes [15]. A larger head size is desirable for hip bearings to improve stability, increase range of motion, and reduce the risk of neck-rim impingement [16, 17]. With the advent of wear resistant, highly crosslinked polyethylenes, the orthopedic community has shifted to using femoral heads up to 44 mm largely on the basis of encouraging in vitro test data [1]. Although larger head sizes are desirable for stability, they come at the expense of modifying the acetabular liner design with reduced polyethylene thickness. Today, utilizing the largest head sizes currently available, highly crosslinked liners are available with a minimum thickness of 4 mm [1]. The preliminary results on head size from our retrieval analysis provide a useful basis for powering a future study on this topic.

The findings from this retrieval study also document a range of ceramic bearing materials in use clinically. Alumina and zirconia are historical ceramic biomaterials, whereas oxidized zirconium (Oxinium) and alumina matrix composites (Biolox Delta) represent relatively new ceramic materials, clinically introduced for polyethylene hip bearings within the past decade [1]. Oxinium femoral heads are made of the metallic Zr-2.5Nb alloy, which is subsequently oxidized at high temperatures to promote a thin (5 microns) surface ceramic (monoclinic) layer of zirconia [18]. In contrast, Biolox Delta consists of an alumina matrix and 17% volume of homogeneously dispersed zirconia nanoparticles [19]. The influence of ceramic femoral heads on THA wear has been a controversial topic for the orthopedic community. Despite the theoretical advantages of ceramic femoral heads, component fracture remains a relevant clinical risk, even with modern bearings in the 21st century. In 2001, Desmarquest announced a world wide recall of zirconia femoral heads due to slight changes in manufacturing conditions [20]. In the present retrieval study, 3 bearings were revised due to late fracture of a recalled zirconia femoral head after 3.7–8.0 years of implantation. We were unable to detect a significant difference between CoCr and ceramic femoral heads based on the sample size of our retrieved ceramic collection. Additional retrieval studies are needed to confirm the long-term stability of oxidized zirconium and alumina matrix composite femoral heads used in conjunction with highly crosslinked polyethylene bearings.

Previous retrieval studies have documented high in vivo oxidation at the rim in annealed and conventional liners [25–28]. In the current study, one case of rim fracture of an annealed liner was associated with edge loading, impingement, and instability. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case of rim fracture reported for annealed liners. The orthopedic practice in which this liner was implanted used the first-generation annealed liners continuously in 5900 cases between 1999 to 2005, during which time retrievals were collected consecutively up until the present time [26]. Thus, the rim fracture rate for annealed liners, based on our study and the published literature, is 1 in approximately six thousand over a ten-year period. Rim delamination after removal, as shown by previous case studies, has been associated with instability, impingement, mechanical loosening, and pelvic fracture [26, 27]. For all these cases, rim damage and fracture of annealed liners appear to be the symptoms, rather than the cause, of a biomechanically malfunctioning total hip arthroplasty.

Adverse clinical loading scenarios have also been shown to result in early rim fracture for remelted liners of varying manufacturers [21–24]. These previous studies do not disclose the number of patients implanted at their centers, nor did we observe any in vivo remelted liners fracture in our series. We are thus unable to calculate a fracture rate for remelted liners at this time for comparison with annealed liners. Furthermore, we did not find a positive correlation between implantation time and femoral head penetration for annealed or remelted liners, which would imply that in vivo oxidation was negatively impacting wear. Overall, rim damage and wear were generally not a clinical concern for either the annealed or remelted materials in the designs and follow-up considered here. Detailed analysis of in vivo oxidation of these retrievals is underway and will be reported in a separate study.

Retrieval analyses are designed primarily to elucidate clinical failure modes under “real-world” conditions, rather than to compare the absolute rates at which failures take place in a prospective randomized study design. Although we have some information regarding the population of annealed liners at one of the high volume centers supplying retrievals to the study, in general the total denominator of cases at every site was unknown. Without this information, our study is necessarily limited to characterizing the relative incidence in reported reasons for revision, as shown in Figure 1. Another limitation, as well as a strength, inherent in retrieval analysis is that the revisions reflect real world implant selection criteria, in which multiple hip arthroplasty configurations are chosen over time and across institutions. Unless the sample size from each subgroup is sufficiently large, it remains difficult to draw conclusions about the effects of head size and head material in each subgroup. On the other hand, the study is adequately powered to detect differences in penetration rate between gamma inert and annealed or remelted liners. These limitations are inherent in retrieval analysis and do not detract from the clinical significance of such studies.

The long-term clinical prospects for first-generation highly crosslinked polyethylenes remain promising, based on their outcomes documented in this study. In the first decade of service, we observed not only a reduction in femoral head penetration, but also that the polyethylene formulation, whether annealed or remelted, did not appear to significantly impact the reasons for revision. Although not generally associated with revision in our series, previous findings of rim oxidation (in annealed liners) and incipient cracks (in remelted liners) provides motivation to continue to monitor first-generation highly crosslinked materials into their second decade of service, as the long-term clinical significance of these observations remains unclear. It also remains too early to determine the potential drawbacks or risks (if any) associated with larger femoral heads and the recently introduced ceramic bearing materials used in conjunction with highly crosslinked polyethylene. In light of the running changes in polyethylene formulations, ceramic bearing materials, and acetabular liner designs with reduced thickness that continue to evolve over time, additional follow-up of our retrieval program will be needed to determine whether the wear reduction observed in the first decade with highly crosslinked polyethylene results in a lower incidence of late revisions for aseptic loosening.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to William Hozack, M.D., Matthew Austin, M.D., and Peter Sharkey, M.D., Rothman Institute at Thomas Jefferson University; Bernard Stulberg, M.D., Cleveland Clinic, Center for Joint Reconstruction; Gregg Klein, M.D., Harlan Levine, M.D., and Mark Hartzband, M.D., Hartzband Center for Hip and Knee Replacement and Hackensack University Medical Center; Jonathan Garino, M.D., Craig Israelite, M.D., and Charles Nelson, M.D., University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; and Victor Goldberg, M.D., Case Western Reserve University, University Hospitals Case Medical Center for their collaboration and contributions to the retrieval program. Thanks are also extended to Rebecca Moore, Case Western Reserve University, and Ashlyn Sakona, Drexel University, for assistance with the retrieval analysis. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIAMS) R01 AR47904. Institutional support has been received from Stryker, Zimmer, Sulzer, and the Wilbert J. Austin Professor of Engineering Chair (CMR).

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Implant Research Center, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kurtz SM. The UHMWPE Biomaterials Handbook: Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene in Total Joint Replacement and Medical Devices. 2. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):128. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurtz SM, Hozack W, Turner J, Purtill J, MacDonald D, Sharkey P, Parvizi J, Manley M, Rothman R. Mechanical properties of retrieved highly cross-linked Crossfire liners after short-term implantation. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7):840. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zahiri CA, Schmalzried TP, Szuszczewicz ES, Amstutz HC. Assessing activity in joint replacement patients. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(8):890. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(98)90195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Barrena E, Li S, Furman BS, Masri BA, Wright TM, Salvati EA. Role of polyethylene oxidation and consolidation defects in cup performance. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1998;(352):105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez-Barrena E, Li S, Furman BS, Masri BA, Wright TM, Salvati EA. Role of polyethylene oxidation and consolidation defects in cup performance. Clin Orthop. 1998;352(352):105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martell JM, Verner JJ, Incavo SJ. Clinical performance of a highly cross-linked polyethylene at two years in total hip arthroplasty: A randomized prospective trial. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2003;18(7):55. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martell JM, Verner JJ, Incavo SJ. Clinical performance of a highly cross-linked polyethylene at two years in total hip arthroplasty: a randomized prospective trial. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(7 Suppl 1):55. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris WH. The problem is osteolysis. Clinical Orthopaedics. 1995;311:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmalzried TP, Dorey FJ, McKellop H. The multifactorial nature of polyethylene wear in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(8):1234. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199808000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright TM, Goodman SB. Implant Wear. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ince A, Rupp J, Frommelt L, Katzer A, Gille J, Lohr JF. Is “aseptic” loosening of the prosthetic cup after total hip replacement due to nonculturable bacterial pathogens in patients with low-grade infection? Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(11):1599. doi: 10.1086/425303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dempsey KE, Riggio MP, Lennon A, Hannah VE, Ramage G, Allan D, Bagg J. Identification of bacteria on the surface of clinically infected and non-infected prosthetic hip joints removed during revision arthroplasties by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and by microbiological culture. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(3):R46. doi: 10.1186/ar2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi N, Procop GW, Krebs V, Kobayashi H, Bauer TW. Molecular identification of bacteria from aseptically loose implants. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1716. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0263-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livermore J, Ilstrup D, Morrey B. Effect of femoral head size on wear of the polyethylene acetabular component. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1990;72(4):518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowninshield RD, Maloney WJ, Wentz DH, Humphrey SM, Blanchard CR. Biomechanics of large femoral heads: what they do and don’t do. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(429):102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burroughs BR, Hallstrom B, Golladay GJ, Hoeffel D, Harris WH. Range of motion and stability in total hip arthroplasty with 28-, 32-, 38-, and 44-mm femoral head sizes. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(1):11. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheth NP, Lementowski P, Hunter G, Garino JP. Clinical applications of oxidized zirconium. Journal of surgical orthopaedic advances. 2008;17(1):17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Affatato S, Torrecillas R, Taddei P, Rocchi M, Fagnano C, Ciapetti G, Toni A. Advanced nanocomposite materials for orthopaedic applications. I. A long-term in vitro wear study of zirconia-toughened alumina. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006;78(1):76. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke IC, Manaka M, Green DD, Williams P, Pezzotti G, Kim YH, Ries M, Sugano N, Sedel L, Delauney C, Nissan BB, Donaldson T, Gustafson GA. Current status of zirconia used in total hip implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A Suppl. 2003;4:73. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300004-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halley D, Glassman A, Crowninshield RD. Recurrent dislocation after revision total hip replacement with a large prosthetic femoral head. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(4):827. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200404000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tower SS, Currier JH, Currier BH, Lyford KA, Van Citters DW, Mayor MB. Rim cracking of the cross-linked longevity polyethylene acetabular liner after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(10):2212. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore KD, Beck PR, Petersen DW, Cuckler JM, Lemons JE, Eberhardt AW. Early failure of a cross-linked polyethylene acetabular liner. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(11):2499. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffy GP, Wannomae KK, Rowell SL, Muratoglu OK. Fracture of a cross-linked polyethylene liner due to impingement. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(1):158, e15. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtz SM, Hozack WJ, Purtill JJ, Marcolongo M, Kraay MJ, Goldberg VM, Sharkey PF, Parvizi J, Rimnac CM, Edidin AA. 2006 Otto Aufranc Award Paper: significance of in vivo degradation for polyethylene in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:47. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000246547.18187.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtz SM, Austin MS, Azzam K, Sharkey PF, Macdonald DW, Medel FJ, Hozack WJ. Mechanical Properties, Oxidation, and Clinical Performance of Retrieved Highly Cross-Linked Crossfire Liners After Intermediate-Term Implantation. J Arthroplasty. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Currier BH, Currier JH, Mayor MB, Lyford KA, Collier JP, Van Citters DW. Evaluation of oxidation and fatigue damage of retrieved crossfire polyethylene acetabular cups. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(9):2023. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medel FJ, Kurtz SM, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, MacDonald D, Kraay MJ, Goldberg V, Rimnac CM. Gamma inert sterilization: a solution to polyethylene oxidation? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(4):839. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]