Abstract

Adult neurogenesis occurs only in discrete regions of adult central nervous system: the subventricular zone and the subgranular zone. These areas are populated by adult neural stem cells (aNSC) that are regulated by a number of molecules and signaling pathways, which control their cell fate choices, survival and proliferation rates. For a long time, it was believed that the immune system did not exert any control on neural proliferative niches. However, it has been observed that many pathological and inflammatory conditions significantly affect NSC niches. Even more, increasing evidence indicates that chemokines and cytokines play an important role in regulating proliferation, cell fate choices, migration and survival of NSCs under physiological conditions. Hence, the immune system is emerging is an important regulator of neurogenic niches in the adult brain, which may have clinical relevance in several brain diseases.

Introduction

For most of last century, it was believed that cell proliferation in the brain was limited to glial cells, the supportive cells found around neurons. In the 1960s, newborn neurons were first described [1]. In the 1980's and 1990's, neurogenesis was demonstrated in the telencephalon of lizards, adult birds and in several mammalian species: mouse, rat, rabbit, cow, primate and humans [2-9]. In mammals, new neurons are continuously added to restricted brain regions, the olfactory bulb and the hippocampus. In these regions, new neurons are functional and appear to modulate olfaction and memory formation, respectively. New neurons in the adult nervous system derive from adult neural stem cells (aNSC), a group of cells that can self-renew and differentiate into all types of neural cells, including neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes.

The brain is an immune-privileged organ because the selective permeability of the blood-brain barrier only allows certain substances and cells to enter and leave. Under normal physiological conditions, only macrophages, T cells and dendritic cells can access the brain [10-12]. After damage, an inflammatory process is initiated by the activation of astrocytes and microglia. This event is followed by parenchymal infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes. The recruited immune cells release many anti- and pro-inflammatory mediators, chemokines, neurotransmitters and reactive oxygen species. This process generates the production and releasing of multiple inflammatory factors, which produces a positive feedback loop that results in both detrimental and positive consequences to neurogenesis [11, 13, 14]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that immune system regulates aNSC population through production of chemokines and cytokines [12, 13, 15]. aNSC have been proposed as an alternative for brain repair therapies but the molecular mechanisms that control survival, proliferation and cell fate are to be elucidated. In this chapter, we summarize emergent evidence indicating that immune mediators control aNSC population under physiological and pathological conditions.

1. The Brain Niches of Adult Neural Stem Cells

Active neurogenesis occurs only in discrete regions of the adult central nervous system. There are two regions were adult neurogenesis has been indisputably described: the subventricular zone (SVZ) and the subgranular zone within the hippocampus (SGZ). Some reports claim that neurogenesis may also occur in other brain areas, including amygdala [16], neocortex [17, 18], substantia nigra [19, 20], and striatum [21, 22]. However, neurogenesis in these areas appears to occur either at substantially lower levels or under non-physiological conditions.

1.1 The subventricular zone (SVZ)

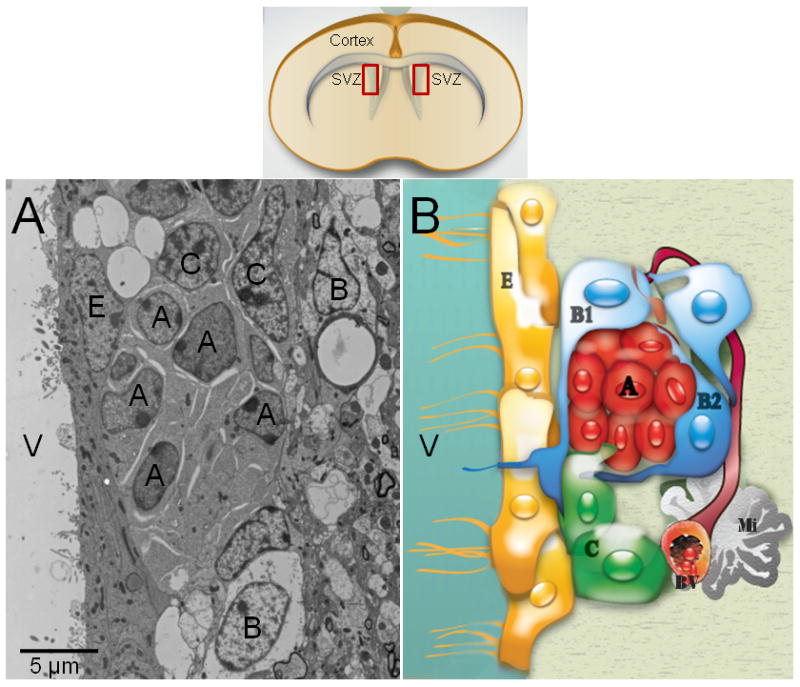

The most important germinal region is the SVZ (figure 1), which contains a subpopulation of astrocytes that function in vivo as aNSCs. SVZ astrocyte NSCs are also known as Type-B cells. Currently Type-B cells are divided into two subtypes: B1 and B2. Type-B1 cells make contact with the ventricular cavity while B2 cells do not. Type-B1 cells show one short primary cilium towards the ventricular cavity (figure 1), which is important to control cell proliferation and posse a long expansion that contact blood vessels [23]. Type-B1 cells give rise to intermediate neural progenitors defined actively proliferating transit amplifying progenitors or Type-C cells. Type-C cells symmetrically divide to produce migrating neuroblasts (Type-A cells) that migrate ventrally through the RMS into the olfactory bulb to become interneurons [24-26], which appear to regulate the olfaction process [27]. Recently, it has been described that Type-B cells in vivo generate oligodendrocytes that migrate into the corpus callosum and fimbria fornix [28, 29]. Blood vessels play an important role in the SVZ and there is evidence that the activation of neurogenic niches is regulated by this vascular network [30].

Fig. 1. The adult subventricular zone in rodent.

This neurogenic niche has been well-characterized by electron microscopy (A). Type-A cells (migrating neuroblasts) have an elongated cell body with one or two processes, profuse lax chromatin with small nucleoli (2 to 4), a scarce dark cytoplasm, abundant free ribosomes, microtubules oriented along the long axis of the cells, and nuclei occasionally invaginated. Their cytoplasmic membrane showed cell junctions intercalated with large intercellular spaces. Type-B cells have a light cytoplasm with a few ribosomes, extensive intermediate filaments and nuclei are typically invaginated. Their cell profiles are irregular that filled intercellular spaces between neighboring cells. Type-C cells are large and semi-spherical; their nuclei contain deep invaginations, lax chromatin occasionally clumped and large reticulated nucleoli. Type-C-cell cytoplasm is more electron-lucent than Type-A cells, but more electron-dense than Type-B cells, because it contains a few ribosomes and no intermediate filaments. Schematic drawing of the adult SVZ shows the cell organization of this region (B). Ependymal cells (Type-E cells) formed an epithelial monolayer that separates the SVZ from the lateral ventricles. These cells have spherical nuclei with lax chromatin, lateral cytoplasmic processes heavily interdigitated with apical junction complexes. The cell membrane contacting the ventricle contains microvilli and cilia, and their cytoplasm is electron-lucent with many mitochondria and basal bodies in the apical pole. A: Type-A cell; B: Type-B cell; C: Type-C cell cell; E: Ependymal cell; BV: Blood vessel; Mi: Microglia cell; V: Ventricle.

1.2 The subgranular zone (SGZ)

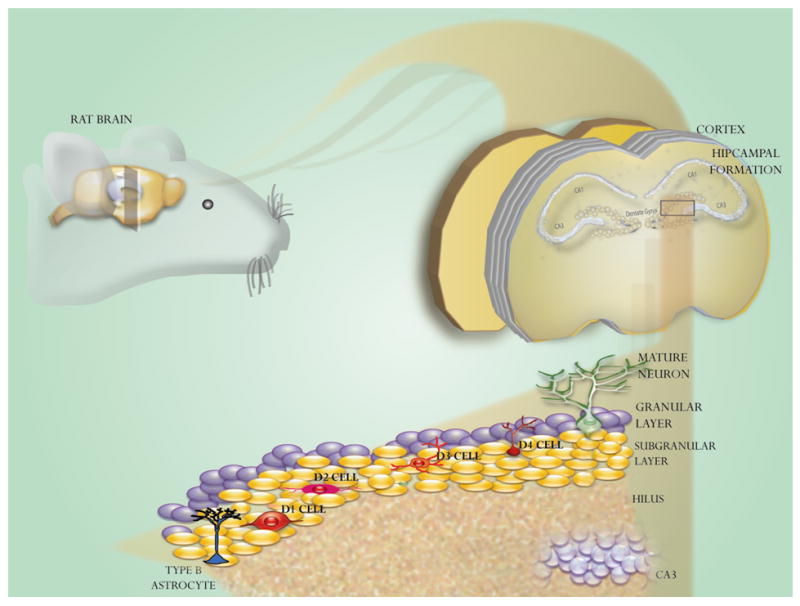

The SGZ of the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus is a proliferative region that contains neuronal progenitors that give rise to granular neurons (figure 2). The primary progenitors in this region are Type-B astrocytes, which have shown in vitro, via neurosphere and adherent monolayer cultures, multipotential properties. In vivo, SGZ Type-B cells appear to have limited capacity for differentiation. Therefore, some authors consider SGZ precursors as neuronal progenitors instead of aNSCs. SGZ Type-B cells divide asymmetrically to give rise to type-D cells that differentiate locally into mature granular neurons. The function of these newly generated neurons appears to play a role in memory process, learning and depression [31].

Fig. 2. Schematic drawing of adult SGZ in rodent.

Dentate gyrus of adult hippocampus continuously produces new neurons throughout life. Type-B cells are the primary progenitors that give rise to intermediate progenitors named Type-D cells, which give rise to granulate neurons.

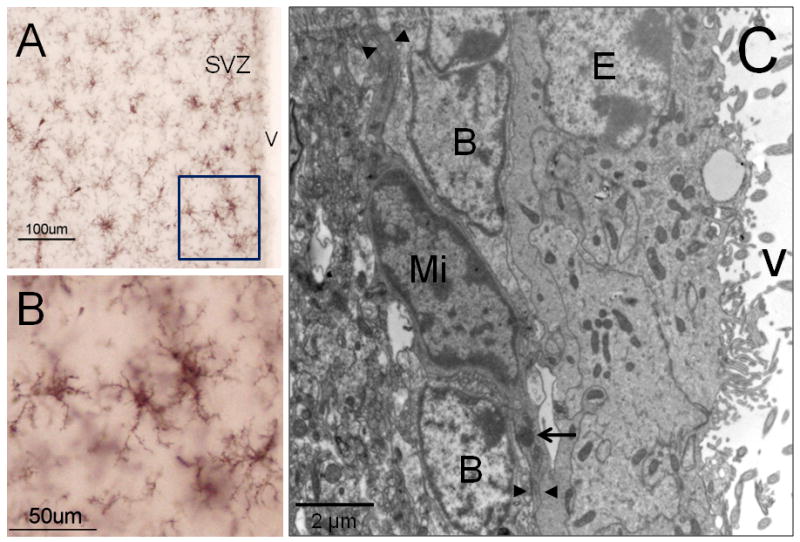

1.3 Microglia in neurogenic niches

Microglia is the main immune effector cell in the nervous system, which have a hematopoietic origin [32] and populate the CNS throughout adulthood [33, 34]. Under physiological conditions microglia is a quiescent cell population, which constantly excavates the CNS for damaged neurons, plaques, and infectious agents [34, 35]. In both, the adult SVZ and SGZ, microglia is abundant and, remarkably, is in close contact to aNSC (Type-B cells), which suggest that local interactions are possible between immune cells and multipotential progenitors (figure 3). Attracted by endogenous and exogenous chemotactic factors, microglial cells constitute the “first line of defense” of the CNS against injury or infections [34]. During inflammation or brain injury, microglia is capable of secreting neurotrophic or neuron survival factors upon activation [35], some of these effects are summarized in the figure 4. Recent evidence indicate that microglia instructs aNSC by secreting factors essential for neurogenesis, but not NSC maintenance, self-renewal, or propagation [36]. These effects seem to be mediated a number of factors, such as: interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) that serve as autocrine activators [11, 37, 38]; interferon gamma (IFN-γ), which thrive the immune response toward a cytotoxic response mediated by Th1 cells [39-42]; insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) that promotes cell proliferation [43]; interleukin-4 (IL-4) that increases phagocytotic properties of microglia [44, 45]; leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) that is usually related to growth promotion and cell differentiation [15, 46-48]. It has been suggested that microglia modulation of aNSC is mediated by activation of mitogen activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways [49]. However, other inflammatory cells produce chemokines and cytokines, which can also influence implicated proliferation, differentiation, survival, and migration of aNSC [50-55]. Their effects will be described in detail in the next section.

Figure 3. Microglia cells in the rodent SVZ.

Iba-1 immunocytochemistry to detect microglia cells by light microscopy (A-B). In their “resting” stage microglia displays multiple thin branches, which confer a ‘bushy’ morphology to these cells. By electron microscopy (C), microglia (Mi) shows a typical dark nucleus and electrodense corpus in their cytoplasm (arrow). Frequently, microglial cytoplasmic expansions (arrow heads) are in close contact with Type-B cells. B: Type-B cell; E: Ependymal cell; V: Ventricle.

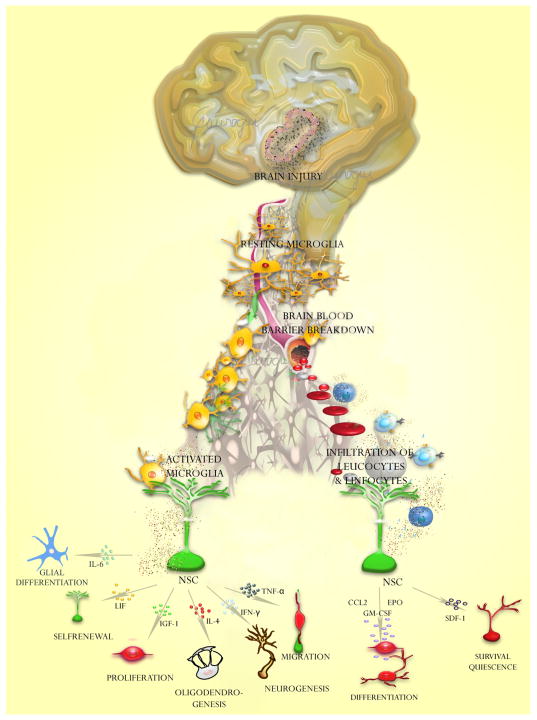

Figure 4. Effects of immune cells on aNSC.

Cell effectors such as microglia, lymphocytes and leucocytes can induce a wide variety of effects on aNSC upon brain injury.

2. Immunological Control of Adult Neural Stem Cells

2.1 Cytokines and chemokines

There are two types of immunological mediators: cytokines and chemokines. Cytokines are polypeptide regulators that have important roles in cellular communication [13]. Most, if not all, cells are regulated by cytokines. In the central nervous system, neuropoietic cytokines are a group of glycoproteins that control neuronal, glial and immune responses to injury or disease. They regulate neuronal growth, regeneration, survival, and differentiation by binding to high affinity receptors. The neuropoietic cytokine family includes interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-18 (IL-18), IFN-γ, LIF, TNF-α, ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and others [13, 15]. Chemokines are small cytokines or proteins (8–14 kDa) that, according to the sequence motif of conserved N-terminal cysteine residues, are categorized into four groups: α-chemokines (CXC chemokines), which promote the migration of neutrophils and lymphocytes; β-chemokines (CC chemokines), which induce the migration of monocytes, NK cells and dendritic cells; γ-chemokines (C chemokines) that attract T cell precursors to the thymus; and δ-chemokines (CX3C chemokines), which serve as a chemoattractants and as an adhesion molecules [12]. Neurons express several receptors for immunological mediators, such as: CCR3, CXCR4, CXCR2, and CX3CR1, while astrocytes mainly express CXCR4, which make them responsive to chemokine gradients in the brain. CXCR4 is also highly expressed on the CD133+/nestin+ human neural precursors [56, 57]. Interestingly, CXCR4 expression is upregulated when embryonic precursors differentiate into neuronal precursors, whereas CXCL12 appears to drive astroglial differentiation [58]. Cytokines and chemokines alter self-renewal, progenitor cell division and differentiation of neural progenitors via JAK/STAT pathway and the Janus kinase-signal transducer [13, 15].

2.2 Effects of cytokines and chemokines on aNSCs

After a brain injury, a number of inflammatory and immunological responses occur that modulate aNSC behavior (Table 1). Activated microglia produces IGF-1, which triggers the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) / mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, increasing neurogenesis in the SGZ [43]. Interestingly, ‘resting’ microglia can also promote aNSC proliferation via the same signaling pathways [49]. Microglia-derived soluble factors such as IL-6 and LIF-1 induces astrocytic differentiation [59]. However, activated microglia appears to have a dual effect on aNSCs, for instance microglia activated by IL-4 drives the generation of oligodendrocytes (the axon supportive and myelin producer cells), whereas the IFN-γ-activated microglia induces a bias towards neurogenesis [44]. Acute LIF or CNTF exposure differentially affects development, growth, amplification and self-renewal of aNSCs [15, 46-48]. Chronic exposure to LIF or CNTF alters the formation of aNSC progenies and promotes aNSC self-renewal [15]. Phosphorylation of STAT3 induced by LIF is essential for maintaining NSC phenotype [60]. Conversely, leptin, which activates STAT3, inhibits differentiation of multipotent cells [15, 61]. aNSCs do not express a functional receptor for IL-6, thus they do not properly respond to IL-6. However, the stimulation of aNSCs with the active fusion protein of IL-6 and sIL-6R, designated as hyper-IL-6, induces aNSCs to differentiate into glutamate-responsive neurons and oligodendrocytes [62]. IFN- γ is pro-neurogenic, promotes neural differentiation and neurite outgrowth of murine aNSCs [39, 40]. However, IFN-γ has shown a dual effect on neurogenesis, because not only stimulate neuronal differentiation [40, 41] and NPC migration, but also inhibits aNSCs proliferation and reduces aNSCs survival [42]. However, the mechanism of this paradoxical effect is unknown. The IFN-γ-induced neuronal differentiation is probably mediated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway [63]. JNK pathway has been involved in neural differentiation of carcinoma cells, embryonic stem cells and PC12 cells [64-67]. Decreased neurogenesis has been observed by effect of TNF-α [11]. However, other studies indicates that TNF-α is a positive regulator of neurogenesis and promotes neurosphere grown by reducing aNSC apoptosis [68]. However, TNF-α increases the expression of MCP-1, a chemokine that induces migration of aNSCs thorough the MCP-1 receptor CCR2 [37, 38]. MCP-1 has protective effects on neurons against excitotoxicity mediated by NMDA receptors [69]. SDF-1 chemokyne promotes migration of neural progenitors and increases survival of aNSCs [37, 70, 71], but contrasting reports demonstrated that SDF-1 has a dual effect on neural progenitors producing quiescence [72] or inducing cell proliferation [73]. Other chemokine as CCL2 has no effects on proliferation and cell survival, but promotes neuronal differentiation of SVZ progenitors [74].

Table 1. Effects of chemokines and cytokines on adult NSCs.

| Cytokine / Chemokine | Effect on aNSCs | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| IFN- γ | Promotion of differentiation and neurite outgrowth. Reduction of proliferation and survival of multipotent progenitors. | [39, 40, 42] |

| IGF-1 | Increasing of neurogenesis in SGZ | [43] |

| IL-4 | Oligodendrogenesis | [44] |

| LIF | Neurogenesis promotions and NSC self-renewal (acute exposure) | [15, 46, 47] |

| CNTF | Neurogenesis promotions and NSC self-renewal (acute exposure) | [15, 79] |

| Leptin | Inhibition of differentiation of multipotent cells and glial progenitors | [15, 61] |

| TNF- α | Decreasing of neurogenesis | [11] |

| H-IL-6 | Differentiation into glutamate-responsive neurons and oligodendrocytes | [62] |

| MCP-1 | Migration of NSCs | [37, 38] |

| SDF-1 | Promotion of migration, survival and proliferation of NSCs | [37, 70, 71, 73] |

| CCL2 | Neuronal differentiation of SVZ progenitors | [74] |

Hematopoietic growth factors have also been involved in the regulation of adult NSCs (figure 4). Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) stimulates neuronal differentiation of aNSCs [75]. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) drives neuronal differentiation of aNSCs in vitro [76] and enhances neurogenesis and functional recovery. Erythropoietin (EPO) drives neuronal differentiation of aNSCs in vitro [77, 78]. Interestingly, EPO-receptor deficient mice display reduced neurogenesis [77, 78]. Yet, as findings in this field are relatively recent, there exist a number of cytokines and chemokines to be investigated as possible regulators of neurogenesis and neuroprotection.

Conclusion

The immunological mediators affect proliferation, survival, migration and differentiation of aNSC (Figure 5). TNF-α, LIF, CNTF, SDF-1 and IGF-1 are considered important regulators of aNSC proliferation. Cell differentiation is driven mainly by IL-6, LIF-1, IL-4, IFN-γ, CCL2, EPO, G-CSF and GM-CSF. Migration of neural progenitors is promoted by MCP-1 and SDF-1, whereas cell survival is positively regulated by TNF-α and SDF-1, but negatively regulated by IFN-γ. In summary, further studies are necessary to elucidate some paradoxical effects on aNSC of immunological factors and signaling pathways involved in these processes.

Figure 5. Immunological mediators have multiple effects on aNSC.

There are some crucial steps in the neurogenic processs: Proliferation, survival, migration, differentiation. Immune effectors that affect proliferation mainly target the SVZ (1). Effectors that modulate survival and migration aim both SVZ and RMS (2), whereas immunological effects on differentiation are reflected in the olfactory bulb (3).

Acknowledgments

OGP was supported by CONACyT's grant (CB-2008-101476). AQH supported by the National Institute of Health, the Howard Hughes Mediacal Institute, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Maryland Stem Cell Foundation. JMGV Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ciberned, Centro de Investigacion Principe Felipe y Red de Terapia Celular, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2008-01274), Alicia Koplowitz's Foundation. We also thank Fernando Jáuregui for assisting with the design and preparation of Figures.

References

- 1.Altman J. Postnatal neurogenesis and the problem of neural plasticity. In: Himwich WA, editor. Developmental neurobiology. C.C.Thomas; Springfield: 1970. pp. 197–237. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman SA, Nottebohm F. Neuronal production, migration, and differentiation in a vocal control nucleus of the adult female canary brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2390–2394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez-Buylla A, Nottebohm F. Seasonal and species differences in the production of long projection neurons in adult birds. Neuroscience. 1989;15:962. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galileo DS, et al. Neurons and glia arise from a common progenitor in chicken optic tectum: Demonstration with two retroviruses and cell type-specific antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:458–462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez-Buylla A, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Tramontin AD. A unified hypothesis on the lineage of neural stem cells. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2. 2(4. 4):287–93. doi: 10.1038/35067582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temple S. The development of neural stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):112–7. doi: 10.1038/35102174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):612–3. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00612.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanai N, et al. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature. 2004;427(6976):740–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. The proliferative ventricular zone in adult vertebrates: a comparative study using reptiles, birds, and mammals. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57(6):765–75. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hickey WF. Leukocyte traffic in the central nervous system: the participants and their roles. Semin Immunol. 1999;11(2):125–37. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitney NP, et al. Inflammation mediates varying effects in neurogenesis: relevance to the pathogenesis of brain injury and neurodegenerative disorders. J Neurochem. 2009;108(6):1343–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonecchi R, et al. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: an overview. Front Biosci. 2009;14:540–51. doi: 10.2741/3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller RJ, et al. Chemokine action in the nervous system. J Neurosci. 2008;28(46):11792–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3588-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das S, Basu A. Inflammation: a new candidate in modulating adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(6):1199–208. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer S. Cytokine control of adult neural stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernier PJ, et al. Newly generated neurons in the amygdala and adjoining cortex of adult primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(17):11464–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172403999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould E, et al. Neurogenesis in the neocortex of adult primates. Science. 1999;286(5439):548–52. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takemura NU. Evidence for neurogenesis within the white matter beneath the temporal neocortex of the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2005;134(1):121–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao M, et al. Evidence for neurogenesis in the adult mammalian substantia nigra. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(13):7925–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131955100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimi K, et al. Possibility for neurogenesis in substantia nigra of parkinsonian brain. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(1):31–40. doi: 10.1002/ana.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Kampen JM, Robertson HA. A possible role for dopamine D3 receptor stimulation in the induction of neurogenesis in the adult rat substantia nigra. Neuroscience. 2005;136(2):381–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bedard A, Gravel C, Parent A. Chemical characterization of newly generated neurons in the striatum of adult primates. Exp Brain Res. 2006;170(4):501–12. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han YG, et al. Hedgehog signaling and primary cilia are required for the formation of adult neural stem cells. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(3):277–84. doi: 10.1038/nn2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Proliferating subventricular zone cells in the adult mammalian forebrain can differentiate into neurons and glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2074–2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alvarez-Buylla A, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Neurogenesis in adult subventricular zone. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):629–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00629.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.So K, et al. The olfactory conditioning in the early postnatal period stimulated neural stem/progenitor cells in the subventricular zone and increased neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb of rats. Neuroscience. 2008;151(1):120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menn B, et al. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26(30):7907–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez-Perez O, et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Induces the Progeny of Subventricular Zone Type B Cells to Migrate and Differentiate into Oligodendrocytes. Stem Cells. 2009;27(8):2032–2043. doi: 10.1002/stem.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen Q, et al. Adult SVZ stem cells lie in a vascular niche: a quantitative analysis of niche cell-cell interactions. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(3):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aimone JB, Wiles J, Gage FH. Potential role for adult neurogenesis in the encoding of time in new memories. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(6):723–7. doi: 10.1038/nn1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eglitis MA, Mezey E. Hematopoietic cells differentiate into both microglia and macroglia in the brains of adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(8):4080–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuadros MA, Navascues J. Early origin and colonization of the developing central nervous system by microglial precursors. Prog Brain Res. 2001;132:51–9. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(01)32065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tambuyzer BR, Ponsaerts P, Nouwen EJ. Microglia: gatekeepers of central nervous system immunology. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(3):352–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0608385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pivneva TA. Microglia in normal condition and pathology. Fiziol Zh. 2008;54(5):81–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walton NM, et al. Microglia instruct subventricular zone neurogenesis. Glia. 2006;54(8):815–25. doi: 10.1002/glia.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Widera D, et al. MCP-1 induces migration of adult neural stem cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83(8):381–7. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwamborn J, et al. Microarray analysis of tumor necrosis factor alpha induced gene expression in U373 human glioblastoma cells. BMC Genomics. 2003;4(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johansson S, Price J, Modo M. Effect of inflammatory cytokines on major histocompatibility complex expression and differentiation of human neural stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(9):2444–54. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong G, Goldshmit Y, Turnley AM. Interferon-gamma but not TNF alpha promotes neuronal differentiation and neurite outgrowth of murine adult neural stem cells. Exp Neurol. 2004;187(1):171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song JH, et al. Interferon gamma induces neurite outgrowth by up-regulation of p35 neuron-specific cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activator via activation of ERK1/2 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(13):12896–901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ben-Hur T, et al. Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on the growth, fate, and motility of multipotential neural precursor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24(3):623–31. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi YS, et al. IGF-1 receptor-mediated ERK/MAPK signaling couples status epilepticus to progenitor cell proliferation in the subgranular layer of the dentate gyrus. Glia. 2008;56(7):791–800. doi: 10.1002/glia.20653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butovsky O, et al. Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-gamma differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31(1):149–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Zahn J, et al. Microglial phagocytosis is modulated by pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Neuroreport. 1997;8(18):3851–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199712220-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauer S, Patterson PH. Leukemia inhibitory factor promotes neural stem cell self-renewal in the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26(46):12089–99. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3047-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oshima K, et al. LIF promotes neurogenesis and maintains neural precursors in cell populations derived from spiral ganglion stem cells. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Covey MV, Levison SW. Leukemia inhibitory factor participates in the expansion of neural stem/progenitors after perinatal hypoxia/ischemia. Neuroscience. 2007;148(2):501–9. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROSCIENCE.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan SC, Taylor DL, Pocock JM. Microglia release activators of neuronal proliferation mediated by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt and delta-Notch signalling cascades. J Neurochem. 2004;90(1):89–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faiz M, et al. Substantial migration of SVZ cells to the cortex results in the generation of new neurons in the excitotoxically damaged immature rat brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38(2):170–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu XS, et al. Functional response to SDF1 alpha through over-expression of CXCR4 on adult subventricular zone progenitor cells. Brain Res. 2008;1226:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robin AM, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha mediates neural progenitor cell motility after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26(1):125–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tiveron MC, et al. Molecular interaction between projection neuron precursors and invading interneurons via stromal-derived factor 1 (CXCL12)/CXCR4 signaling in the cortical subventricular zone/intermediate zone. J Neurosci. 2006;26(51):13273–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4162-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan YP, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 plays a critical role in neuroblast migration after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(6):1213–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhattacharyya BJ, et al. The chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 regulates GABAergic inputs to neural progenitors in the postnatal dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2008;28(26):6720–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1677-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ni HT, et al. High-level expression of functional chemokine receptor CXCR4 on human neural precursor cells. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152(2):159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tran PB, et al. Chemokine receptors are expressed widely by embryonic and adult neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76(1):20–34. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng H, et al. Differential expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4 during human fetal neural progenitor cell differentiation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2007;2(3):251–8. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakanishi M, et al. Microglia-derived interleukin-6 and leukaemia inhibitory factor promote astrocytic differentiation of neural stem/progenitor cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(3):649–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burdon T, Smith A, Savatier P. Signalling, cell cycle and pluripotency in embryonic stem cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12(9):432–8. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Udagawa J, Nimura M, Otani H. Leptin affects oligodendroglial development in the mouse embryonic cerebral cortex. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006;27(1-2):177–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Islam O, et al. Interleukin-6 and neural stem cells: more than gliogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(1):188–99. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim SJ, et al. Interferon-gamma promotes differentiation of neural progenitor cells via the JNK pathway. Neurochem Res. 2007;32(8):1399–406. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9323-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zentrich E, et al. Collaboration of JNKs and ERKs in nerve growth factor regulation of the neurofilament light chain promoter in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(6):4110–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Akiyama S, et al. Activation mechanism of c-Jun amino-terminal kinase in the course of neural differentiation of P19 embryonic carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(35):36616–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang H, et al. Activation of c-Jun amino-terminal kinase is required for retinoic acid-induced neural differentiation of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2001;503(1):91–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amura CR, et al. Inhibited neurogenesis in JNK1-deficient embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(24):10791–802. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10791-10802.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Widera D, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha triggers proliferation of adult neural stem cells via IKK/NF-kappaB signaling. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eugenin EA, et al. MCP-1 (CCL2) protects human neurons and astrocytes from NMDA or HIV-tat-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2003;85(5):1299–311. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peng H, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1-mediated CXCR4 signaling in rat and human cortical neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76(1):35–50. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Molyneaux KA, et al. The chemokine SDF1/CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 regulate mouse germ cell migration and survival. Development. 2003;130(18):4279–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.00640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krathwohl MD, Kaiser JL. HIV-1 promotes quiescence in human neural progenitor cells. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(2):216–26. doi: 10.1086/422008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gong X, et al. Stromal cell derived factor-1 acutely promotes neural progenitor cell proliferation in vitro by a mechanism involving the ERK1/2 and PI-3K signal pathways. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30(5):466–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu XS, et al. Chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) induces migration and differentiation of subventricular zone cells after stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(10):2120–5. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kruger C, et al. The hematopoietic factor GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) promotes neuronal differentiation of adult neural stem cells in vitro. BMC Neurosci. 2007;8:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-8-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schneider A, et al. The hematopoietic factor G-CSF is a neuronal ligand that counteracts programmed cell death and drives neurogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2083–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI23559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen ZY, et al. Endogenous erythropoietin signaling is required for normal neural progenitor cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(35):25875–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shingo T, et al. Erythropoietin regulates the in vitro and in vivo production of neuronal progenitors by mammalian forebrain neural stem cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21(24):9733–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09733.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shimazaki T, Shingo T, Weiss S. The ciliary neurotrophic factor/leukemia inhibitory factor/gp130 receptor complex operates in the maintenance of mammalian forebrain neural stem cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21(19):7642–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07642.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]