Abstract

Background

Mutations in Parkin are the most common cause of autosomal recessive Parkinson disease (PD). The mitochondrially localized E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Parkin has been reported to be involved in respiratory chain function and mitochondrial dynamics. More recent publications also described a link between Parkin and mitophagy.

Methodology/Principal Findings

In this study, we investigated the impact of Parkin mutations on mitochondrial function and morphology in a human cellular model. Fibroblasts were obtained from three members of an Italian PD family with two mutations in Parkin (homozygous c.1072delT, homozygous delEx7, compound-heterozygous c.1072delT/delEx7), as well as from two relatives without mutations. Furthermore, three unrelated compound-heterozygous patients (delEx3-4/duplEx7-12, delEx4/c.924C>T and delEx1/c.924C>T) and three unrelated age-matched controls were included. Fibroblasts were cultured under basal or paraquat-induced oxidative stress conditions. ATP synthesis rates and cellular levels were detected luminometrically. Activities of complexes I-IV and citrate synthase were measured spectrophotometrically in mitochondrial preparations or cell lysates. The mitochondrial membrane potential was measured with 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide. Oxidative stress levels were investigated with the OxyBlot technique. The mitochondrial network was investigated immunocytochemically and the degree of branching was determined with image processing methods. We observed a decrease in the production and overall concentration of ATP coinciding with increased mitochondrial mass in Parkin-mutant fibroblasts. After an oxidative insult, the membrane potential decreased in patient cells but not in controls. We further determined higher levels of oxidized proteins in the mutants both under basal and stress conditions. The degree of mitochondrial network branching was comparable in mutants and controls under basal conditions and decreased to a similar extent under paraquat-induced stress.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that Parkin mutations cause abnormal mitochondrial function and morphology in non-neuronal human cells.

Introduction

Mutations in the Parkin gene (MIM 602544) are the most common known cause of early-onset Parkinson disease (PD; MIM 168600), accounting for up to 77% of the cases with an age of onset <30 years [1]. Parkin encodes a 465-amino-acid protein with a modular structure [2], [3].

In addition to Parkin's roles as E3 ligase and neuroprotectant, it has been reported to be involved in mitochondrial function [4]. This connection was first established when Parkin loss-of-function mice presented with reduced expression of mitochondrial function- and oxidative stress-related proteins, decreased mitochondrial respiratory capacity and increased oxidative damage [5]. Similar results were obtained in additional animal models [6], [7], [8], [9].

Investigation of mitochondrial function in human samples supports the findings from animal studies. Functional assays in leukocytes as well as fibroblasts of patients with homozygous or compound-heterozygous Parkin mutations consistently showed reduced mitochondrial complex I activity, coinciding with reduced ATP synthesis rates [10], [11].

Another intriguing finding is that Parkin is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial morphology. The knockdown of Parkin causes swollen mitochondria in Drosophila indirect flight muscles [12], [13]. As a human model, fibroblasts from PD patients with Parkin mutation have been used to investigate mitochondrial morphology and revealed a greater degree of mitochondrial branching in the patients than in controls [11].

Recently, several publications linked Parkin and mitophagy in different cellular models [14], [15], [16], [17]. Induced by loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, Parkin is recruited by the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1; MIM 608309) to dysfunctional mitochondria, where it mediates their engulfment by autophagosomes and their selective elimination [14], [17], [18], [19]. In Drosophila, terminally damaged mitochondria are labeled for degradation by ubiquitylation of mitofusion (mfn) [20], [21], [22].

Most of the above-mentioned data explaining Parkin's function with respect to PD were either obtained in animal models or in small sets of human cellular samples. Here, we evaluated a larger sample of Parkin-mutant fibroblasts for changes in mitochondrial function and morphology.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Lübeck and all participants gave written, informed consent.

Patients

Skin biopsies were obtained from 11 individuals including six affected cases (mean age ± STD: 56.2±13.3 years) with two mutant Parkin alleles and five age-matched controls (mean age±STD: 51.8±11.5 years) without mutations in known PD genes. Phenotypic and genotypic data are summarized in Table 1 (further clinical details were published earlier [23]).

Table 1. Table 1. Genotypic and phenotypic characterisation of investigated individuals.

| Code | Sex | Age of onset (yr) | Age (yr) | Mutation | Zygosity | Clinical status | |

| Mutants | B11 | M | 64 | 79 | delEx7+c.1072delT | compound heterozygous | affected |

| B125 | M | 43 | 62 | c.1072delT | homozygous | affected | |

| B300 | F | 34 | 49 | delEx7 | homozygous | affected | |

| L3035 | M | 31 | 49 | delEx3-4+duplEx7-12 | compound heterozygous | affected | |

| L3048 | M | 15 | 57 | delEx4+c.924C>T | compound heterozygous | affected | |

| L3244 | F | 37 | 41 | delEx1+c.924C>T | compound heterozygous | affected | |

| ∅ ± STD | 37.3±16.1 | 56.2±13.3 | |||||

| Controls | 802.1 | F | n/a | 60 | none | n/a | unaffected |

| 902.1 | F | n/a | 68 | none | n/a | unaffected | |

| B963 | M | n/a | 44 | none | n/a | unaffected | |

| B964 | M | n/a | 44 | none | n/a | unaffected | |

| L3293 | M | n/a | 43 | none | n/a | unaffected | |

| ∅ ± STD | 51.8±11.5 |

Tissue culture

Fibroblasts were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (all PAA, Pasching, Austria) at 37°C, 5% CO2. In all assays, fibroblast passage numbers were matched (<15).

To induce oxidative stress, cells were treated with 2 mM paraquat for 24 h (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Assessment of mitochondrial function

Cellular ATP synthesis rates were determined according to a published protocol [24]. In brief, the amount of protein was determined using the Dc Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Fibroblasts were harvested and diluted with cell suspension buffer (150 mmol/l KCl, 25 mmol/l Tris-HCl; pH 7.6, 2 mmol/l EDTA pH 7.4, 10 mmol/l KPO4 pH 7.4, 0.1 mmol/l MgCl2 and 0.1% [w/v] BSA) to a concentration of 1 mg protein per ml. ATP synthesis was initiated by the addition of 250 µl of the cell suspension to 750 µl of substrate buffer (10 mmol/l malate, 10 mmol/l pyruvate, 1 mmol/l ADP, 40 µg/ml digitonin and 0.15 mmol/l adenosine pentaphosphate). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 min. At 0 and 10 min, 50 µl aliquots of the reaction mixture were withdrawn, quenched in 450 µl of boiling 100 mmol/l Tris-HCl, 4 mmol/l EDTA pH 7.75 for 2 min and further diluted 1/10 in the quenching buffer. The quantity of ATP was measured in a luminometer (Berthold, Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany) with the ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) following the manufacturer's instructions. Cellular ATP levels were quantified in intact cells as described [25]. In both assays, the control average value per run was set to 100% and the relative average patient value was calculated. By this, variation of absolute ATP levels between experimental runs due to variable quality of the used kit was not taken into account.

To investigate respiratory chain function, mitochondria were isolated as published [25]. Mitochondrial respiratory chain complex activities were measured spectrophotometrically and expressed as ratios of citrate synthase activity [25].

The mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed using 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) [25].

All measurements were performed in duplicate and in at least three independent runs per sample on a microplate reader (Synergy HT, BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Quantification of oxidized proteins

Protein carbonyl levels were measured with the OxyBlot kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Carbonyl groups in the protein side chains were derivatized to 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNP). Western blot analysis was performed with an antibody against DNP. Equal loading was assessed using an antibody against mouse polyclonal anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The experiment was performed three times and a representative blot was analyzed densitometrically with TotalLab software (Nonlinear Dynamics, Newcastle, UK).

Assessment of mitochondrial branching

The mitochondrial network in fibroblasts was stained with an anti-GRP75 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) in combination with the zenon immunolabelling kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's protocol.

The mitochondrial network morphology was investigated using a fluorescence microscope equipped with an ApoTome and AxioVision software (all Zeiss, Jena, Germany). By means of ImageJ 1.42, raw images were binarized, mitochondrion area and outline were measured and the form factor was calculated (defined as [Pm 2]/[4πAm]), where Pm is the length of the mitochondrial outline and Am is the area of the mitochondrion [11]). The form factor allows quantifying the degree of branching of the mitochondrial network. Images of at least five randomly selected cells per individual were analyzed under basal conditions and after paraquat treatment.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U test was applied for comparisons between mutants and controls. In case of the ATP concentration and synthesis data, a Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare the mutant with the average control values set to 100% in each run. For evaluation of the impact of stress on cells, the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test was used to determine differences before and after treatment. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

We analyzed primary dermal fibroblasts from six PD patients with homozygous or compound-heterozygous mutations and five age-matched controls for mitochondrial changes (Table 1).

Respiratory chain function is impaired in Parkin-mutant fibroblasts

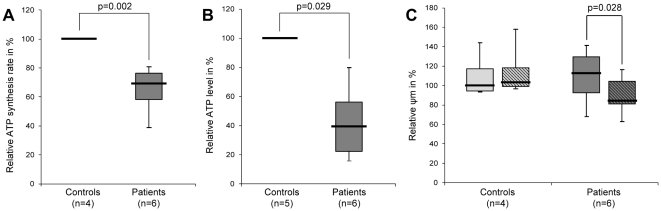

We first determined ATP synthesis rates and cellular ATP concentrations. These experiments revealed a significant (ATP synthesis: p = 0.002; ATP level: p = 0.029) reduction of both parameters in mutants compared to controls (Figure 1A, B).

Figure 1. Mitochondrial function.

(A) Basal ATP synthesis rates. The assay demonstrated a significant reduction in ATP production in the Parkin-mutant patients (median [IQR]: 39% [23%, 55%]) compared to controls (set to 100%). (B) Basal ATP levels. Quantifying the overall cellular ATP concentration showed significantly lower levels in the mutants (median [IQR]: 69% [58%, 75%]) than in controls (set to 100%). (C) Mitochondrial membrane potential under basal and oxidative stress conditions. Control (median [IQR]: 100% [94%, 115%]) and patient fibroblasts (median [IQR]: 113% [93%, 128%]) with Parkin mutations show similar membrane potential under basal conditions. When the cells were treated with paraquat (shaded boxes), no relevant changes were detected in the controls (median [IQR]: 102% [100%, 118%]). In the Parkin mutants, a significant drop of the membrane potential was observed (median [IQR]: 84% [81%, 103%]). The median, the interquartile range (IQR), the minimum and the maximum value of 6 (A) or 4 (B) independent experimental runs are plotted. In each experimental run the average ATP level in the controls was set to 100%.

We next investigated whether the lower ATP synthesis rates and cellular ATP levels in the patient samples were due to a dysfunction of respiratory chain enzymes. Kinetic assays performed in mitochondrial preparations showed no significant differences in complex I activity in patient fibroblasts (median [interquartile range; IQR]: 72% [66%, 87%], n = 6) compared to controls (median [IQR]: 100% [80%, 102%], n = 5). Furthermore, we performed an NADH ferricyanide reductase assay, which allows to determine the content of functional complex I [26]. This assay also showed similar levels in mutants (median [IQR]: 87% [71%, 101%], n = 6) and controls (median [IQR]: 100% [88%, 107%], n = 5). The activities of complexes II+III (median [IQR]: patients, 134% [85%, 180%], n = 6; controls, 100% [92%, 112%], n = 5) and IV (median [IQR]: patients, 95% [82%, 108%], n = 6; controls: 100% [75%, 112%], n = 5) were comparable in Parkin-mutant fibroblasts and controls.

We then went on to determine the mitochondrial membrane potential as a central parameter of mitochondrial integrity. Under basal conditions, the membrane potential was similar in patients and controls, whereas under paraquat-induced stress, the mutants showed a significant (p = 0.028) loss (Figure 1C).

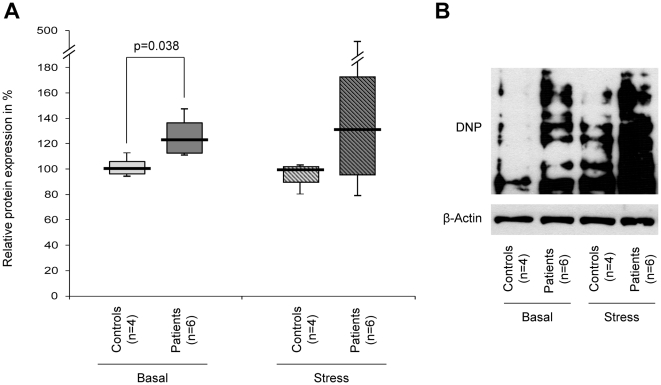

Mutant-Parkin alters the cellular oxidative stress level

In order to determine basal levels of oxidative stress in fibroblasts from Parkin mutants, we applied an OxyBlot. This technique demonstrated significantly (p = 0.038) higher levels of oxidized proteins in the Parkin-mutant samples than in controls (Figure 2A). Under paraquat-induced stress, the difference in oxidation between mutants and controls increased markedly. Due to increased variability of the individual results after stress this result was not significant (Figure 2A). The findings from densitometric analyses in single individuals were supported by an OxyBlot performed with pooled control and patient samples under basal and stress conditions (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Protein oxidation under basal and stress conditions.

Oxidation of proteins in Parkin-mutant fibroblasts and controls was determined by means of an OxyBlot. (A) When quantifying the protein oxidation in each individual using an antibody against DNP, the Parkin mutants (median [IQR]: 123% [113%, 136%]) showed significantly higher levels of oxidation than the controls (median [IQR]: 100% [97%, 105%]). After treatment of the cells with paraquat (shaded boxes), the difference in oxidation between mutants (median [IQR]: 131% [96%, 172%]) and controls (median [IQR]: 100% [90%, 102%]) increased, but was no longer significant. Equal protein loading was verified with an antibody against β-actin. Expression ratios of oxidized proteins vs. β-actin were calculated. The median, the interquartile range (IQR), the minimum and the maximum value of the investigated groups of individuals are given. (B) OxyBlot of pooled protein samples before and after paraquat treatment showing a similar trend as identified by individual measurements.

Mitochondrial mass is increased in Parkin-mutant fibroblasts

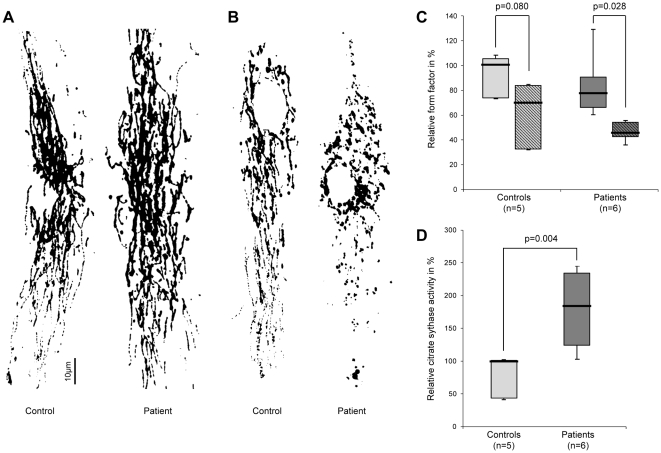

Next, we tested mitochondria of our fibroblast samples for morphological changes since impaired mitochondrial fission [11], [27], [28] or the failure to activate mitophagy [18] are well-established findings in Parkin null mutants.

To compare the degree of mitochondrial network branching in Parkin mutants and controls, we determined the form factor. This morphological assessment demonstrated no differences between mutant and control individuals under basal conditions (Figure 3A–C). After treatment with paraquat, the degree of branching decreased by 34% within the controls and by 46% within the Parkin-mutant samples. This drop was only significant (p = 0.028) in the latter group (Figure 3A–C).

Figure 3. Morphology of the mitochondrial network.

(A) Images of the mitochondrial network in control and patient fibroblasts demonstrating similar degrees of branching under basal culturing conditions. (B) After treatment with paraquat, the network was less branched in patients and controls. (C) The degree of mitochondrial branching (form factor) was comparable in patients (median [IQR]: 78% [66%, 90%]) and controls (median [IQR]: 100% [73%, 105%]) under standard cell culturing conditions. When treated with paraquat (shaded boxes), the form factor decreased significantly in the mutant samples (median [IQR]: 46% [43%, 54%]). By contrast, a drop seen in controls (median [IQR]: 70% [32%, 84%]) was not significant. (D) Citrate synthase activity in cell lysates. Parkin mutants (median [IQR]: 183% [125%, 232%]) showed significantly higher citrate synthase activities than controls (median [IQR]: 100% [43%, 101%]), indicative of increased mitochondrial mass per cell in the former. Citrate synthase activity in cell lysates was normalized for protein concentration. The median, the interquartile range (IQR), the minimum and the maximum value of the investigated groups of individuals are shown.

Finally, to quantify the mitochondrial mass per cell, we determined the citrate synthase activity in cell lysates. These levels were significantly (p = 0.004) higher in mutants than in controls (Figure 3D).

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate that mutations in Parkin cause abnormal mitochondrial function and morphology in PD patient fibroblasts.

Oxidative stress is a key element implicated in the pathophysiology of PD, as recently further supported by studies on human skin fibroblasts from PD patients [11], [25]. Our results demonstrate increased oxidative stress levels in Parkin-mutant fibroblasts under basal conditions. This difference between mutants and controls became more pronounced when the cells were exposed to paraquat. In keeping with our findings, a deficiency of the Parkin interaction partner PINK1 has been reported to cause mitochondrial accumulation of calcium in mammalian neurons, resulting in a mitochondrial calcium overload which then stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via NADPH oxidase [29].

Furthermore, there is strong evidence that a deficit in respiratory chain function is involved in the pathogenesis of PD [30], [31]. In a study on Parkin-mutant fibroblasts, the authors reported that a decrease in ATP production was linked to complex I [11]. Here, we determined significantly reduced ATP synthesis rates and cellular concentrations in patient cells with Parkin mutations compared to controls. By contrast, we saw no significant difference in complex I activity between patient samples and controls. Also the activities of complexes II to IV were not significantly altered in the Parkin-mutant cells. A possible explanation for this discrepancy might be a loss of the electron carrier glutathione or oxidation of ubiquinone due to increased oxidative stress in the patient cells.

When quantifying the mitochondrial membrane potential as a central factor of mitochondrial integrity [14], we found no impairment in the Parkin mutants under basal culturing conditions. However, exposure to high levels of ROS caused a significant decline of the membrane potential in these cells. In an earlier study, the membrane potential was found to be decreased in Parkin-mutant fibroblasts already under basal conditions and culturing in glucose depletion medium supplemented with galactose further worsened the situation [11]. If the mitochondrial membrane potential data were corrected for mitochondrial mass per cell, a similar outcome would be expected in our study.

Recently, Parkin has been shown to act downstream of PINK1 in a common pathway which appears to regulate mitochondrial morphology [27], [28], [32]. Two studies in human cells also demonstrated an impact of mutations in Parkin [11] and PINK1 [25] on the shape of the mitochondrial network. Parkin-mutant cells were found to be more prone to enter fusion as reflected by a significant increase in mitochondrial branching in the patient group [11]. By contrast, we detected no significant differences in the degree of branching between Parkin mutants and controls under basal conditions but an increase in mitochondrial mass in the former. In the above-mentioned study [11], fibroblasts were exposed to rotenone, an inhibitor of the respiratory chain complex I. This treatment induced mitochondrial fragmentation in Parkin-mutant and control cells to a comparable extent. Similarly, in our study, no significant differences in branching between mutants and controls were detected after exposure to paraquat.

In light of the most recent publications ascribing Parkin a role in promotion of mitophagy [14], [15], [16], [17] our results can be interpreted as consequences of the inability of mutant Parkin to perform its function. In Drosophila, the initiation of mitophagy depends on ubiquitylation of the fusion factor mfn by parkin. Following mfn ubiquitylation, dysfunctional mitochondria are prevented from re-fusion with functional mitochondria [20], [21], [22]. If this ubiquitylation is impaired in Parkin mutants under stress, one could imagine that mitochondria with disturbed respiratory chain function are no longer separated and eliminated from the general pool but dominate cellular (dys)function. This effect is in keeping with decreased ATP synthesis rates, elevated oxidized protein levels, increased mitochondrial mass and the observed stress-induced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in the patient fibroblasts investigated here. Furthermore, one would expect that due to impaired Mfn1/2 deactivation/degradation, mitochondria should be less fragmented in Parkin-mutant than in control cells under stress conditions. Since mitochondrial fusion and fission are transient events, dynamic techniques to quantify the degree of mitochondrial branching would be preferable to the method established so far [11]. Methodological restrictions together with great inter-individual variations in branching especially after exposure to mitochondrial stressors render it impossible to detect subtle morphological differences between mutants and controls.

In the future, further investigations of the relationship between changes in mitochondrial dynamics/turnover and cell death will be necessary to identify potential targets for neuroprotective drugs redirecting Parkin-mutant cells towards survival. The results from our study underline that also non-neuronal cells, such as fibroblasts from patients, allow important insights into the mechanisms underlying PD and, therefore, will be a useful tool to pursue this scientific goal.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Henry Schütze, BSc (Institute for Neuro- and Bioinformatics, University of Lübeck) for computational advice regarding image processing.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: Dr. Schapira is a board member of the Royal Free Hospital trust, served as a consultant for BI, GSK, Teva-Lundbeck, Orion-Novartis and EMD Serono, and received research support from the Kattan Trust. This does not alter the authors' adherence to all the PLoS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (GR 3731/1-1), the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation, the German Academic Exchange Service, the EU Grant GENEPARK (EU-LSHB-CT-2006-037544), the Deutsches Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Nationales Genomforschungsnetz plus, PNP-01GS08135-3), the Volkswagen Foundation, the Hermann and Lilly Schilling Foundation, the Hilde Ulrichs Foundation for Parkinson Disease Research, the Australian Brain Foundation and the Medical Faculty of the University of Lübeck. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lucking CB, Durr A, Bonifati V, Vaughan J, De Michele G, et al. Association between early-onset Parkinson's disease and mutations in the parkin gene. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1560–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005253422103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hristova VA, Beasley SA, Rylett RJ, Shaw GS. Identification of a novel Zn2+-binding domain in the autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson-related E3 ligase parkin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14978–14986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808700200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beasley SA, Hristova VA, Shaw GS. Structure of the Parkin in-between-ring domain provides insights for E3-ligase dysfunction in autosomal recessive Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3095–3100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610548104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore DJ. Parkin: a multifaceted ubiquitin ligase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:749–753. doi: 10.1042/BST0340749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palacino JJ, Sagi D, Goldberg MS, Krauss S, Motz C, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in parkin-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18614–18622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez FA, Palmiter RD. Parkin-deficient mice are not a robust model of parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2174–2179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409598102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itier JM, Ibanez P, Mena MA, Abbas N, Cohen-Salmon C, et al. Parkin gene inactivation alters behaviour and dopamine neurotransmission in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2277–2291. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg MS, Fleming SM, Palacino JJ, Cepeda C, Lam HA, et al. Parkin-deficient mice exhibit nigrostriatal deficits but not loss of dopaminergic neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43628–43635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flinn L, Mortiboys H, Volkmann K, Koster RW, Ingham PW, et al. Complex I deficiency and dopaminergic neuronal cell loss in parkin-deficient zebrafish (Danio rerio). Brain. 2009;132:1613–1623. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muftuoglu M, Elibol B, Dalmizrak O, Ercan A, Kulaksiz G, et al. Mitochondrial complex I and IV activities in leukocytes from patients with parkin mutations. Mov Disord. 2004;19:544–548. doi: 10.1002/mds.10695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mortiboys H, Thomas KJ, Koopman WJ, Klaffke S, Abou-Sleiman P, et al. Mitochondrial function and morphology are impaired in parkin-mutant fibroblasts. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:555–565. doi: 10.1002/ana.21492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene JC, Whitworth AJ, Kuo I, Andrews LA, Feany MB, et al. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4078–4083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pesah Y, Pham T, Burgess H, Middlebrooks B, Verstreken P, et al. Drosophila parkin mutants have decreased mass and cell size and increased sensitivity to oxygen radical stress. Development. 2004;131:2183–2194. doi: 10.1242/dev.01095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Gautier CA, et al. PINK1 Is Selectively Stabilized on Impaired Mitochondria to Activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wild P, Dikic I. Mitochondria get a Parkin' ticket. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:104–106. doi: 10.1038/ncb0210-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RL, et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin-induced mitophagy in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. Autophagy. 2009;5:706–708. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda N, Sato S, Shiba K, Okatsu K, Saisho K, et al. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:211–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poole AC, Thomas RE, Yu S, Vincow ES, Pallanck L. The mitochondrial fusion-promoting factor mitofusin is a substrate of the PINK1/parkin pathway. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziviani E, Tao RN, Whitworth AJ. Drosophila parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates mitofusin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913485107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ziviani E, Whitworth AJ. How could Parkin-mediated ubiquitination of mitofusin promote mitophagy? Autophagy. 2010;6 doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pramstaller PP, Schlossmacher MG, Jacques TS, Scaravilli F, Eskelson C, et al. Lewy body Parkinson's disease in a large pedigree with 77 Parkin mutation carriers. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:411–422. doi: 10.1002/ana.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shepherd RK, Checcarelli N, Naini A, De Vivo DC, DiMauro S, et al. Measurement of ATP production in mitochondrial disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:86–91. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grünewald A, Gegg ME, Taanman JW, King RH, Kock N, et al. Differential effects of PINK1 nonsense and missense mutations on mitochondrial function and morphology. Exp Neurol. 2009;219:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esposti MD. Assessing Functional Integrity of Mitochondria in Vitro and in Vivo. In: Pon LA, Schon EA, editors. Mitochondria. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 75–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poole AC, Thomas RE, Andrews LA, McBride HM, Whitworth AJ, et al. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1638–1643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng H, Dodson MW, Huang H, Guo M. The Parkinson's disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803998105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandhi S, Wood-Kaczmar A, Yao Z, Plun-Favreau H, Deas E, et al. PINK1-associated Parkinson's disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Mol Cell. 2009;33:627–638. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schapira AH, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Jenner P, Clark JB, et al. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 1989;1:1269. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schapira AH. Mitochondria in the aetiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:97–109. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Exner N, Treske B, Paquet D, Holmstrom K, Schiesling C, et al. Loss-of-function of human PINK1 results in mitochondrial pathology and can be rescued by parkin. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12413–12418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]