Abstract

Objective

This study compared the acute phase (12-week) efficacy of fluoxetine versus placebo for the treatment of the depressive symptoms and the cannabis use of adolescents and young adults with comorbid major depression (MDD) and an cannabis use disorder (CUD)(cannabis dependence or cannabis abuse). We hypothesized that fluoxetine would demonstrate efficacy versus placebo for the treatment of the depressive symptoms and the cannabis use of adolescents and young adults with comorbid MDD/CUD.

Methods

We conducted the first double-blind placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in adolescents and young adults with comorbid MDD/CUD. All participants in both treatment groups also received manual-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivation enhancement therapy (MET) during the 12-week course of the study.

Results

Fluoxetine was well tolerated in this treatment population. No significant group-by-time interactions were noted for any depression-related or cannabis-use related outcome variable over the 12-week study. Subjects in both the fluoxetine group and the placebo group showed significant within-group improvement in depressive symptoms and in number of DSM diagnostic criteria for a CUD. Large magnitude decreases in depressive symptoms were noted in both treatment groups, and end-of-study levels of depressive symptoms were low in both treatment groups.

Conclusions

Fluoxetine did not demonstrate greater efficacy than placebo for treating either the depressive symptoms or the cannabis-related symptoms of our study sample of comorbid adolescents and young adults. The lack of a significant between-group difference in these symptoms may reflect limited medication efficacy, or may result from efficacy of the CBT/MET psychotherapy or from limited sample size.

Keywords: Cannabis Use Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, Fluoxetine, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Motivation Enhancement Therapy

1. Introduction

Cannabis is by far the most commonly used illicit substance in the United States, and has been so for the last several decades (Agosti et al., 2002; Compton et al., 2004; Stinson et al., 2005). The prevalence of current (past-year) cannabis dependence is much higher among adolescents (2.6%) and young adults (3.5%) than among adults 26 years old and older (0.4%) (Dennis et al., 2002; Compton et al., 2004). Cannabis use disorders (CUD) are significantly associated with affective disorders (Regier et al., 1990). Cannabis dependence has been shown to be associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) in multiple large epidemiological studies, with odds ratios of 3.4 (Chen et al., 2002) and 3.0 Stinson et al., 2006).

Despite the prevalence of cannabis use disorders, pharmacotherapy studies involving those disorders are scarce, and studies involving CUD in combination with comorbid disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD) are even less common. Such pharmacotherapy studies in comorbid adolescent and young adult populations are particularly rare. Despite the widespread prevalence of this comorbid condition among adolescents, no previous double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have been conducted involving adolescents with comorbid major depressive disorder and a cannabis use disorder (Nordstrom & Levin, 2007; Cornelius et al., 2007). However, multiple controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of fluoxetine for treating major depressive disorder in adolescents and young adults without a SUD (Emslie, et al., 1997; Emslie et al., 2002; March, et al., 2004; Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team, 2004; Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS), 2007; Emslie et al., 2008). To date, only one study has evaluated the efficacy of an SSRI medication (fluoxetine) among youthful subjects with major depressive disorder and a variety of substance use disorders, including CUD. The sample in that study was somewhat heterogeneous, in that only some of the subjects demonstrated a CUD, and many of them also demonstrated other substance use disorders (SUD), including cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opiates, sedatives, phencyclidine, amphetamines, and club drugs, in addition to a variety of behavior problems (Riggs et al, 2007). No cannabis outcome data was provided in that paper. Rather, outcome data was provided regarding days of nontobacco drug use. That study found that fluoxetine plus cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) displayed greater efficacy than did placebo plus CBT on one but not both depression measures, and was not associated with greater decline in self-reported substance use. The authors of that study also concluded that CBT may have contributed to higher-than-expected treatment response and mixed efficacy findings, despite its focus on SUD. To date, the results of that study have not been replicated nor refuted, and no studies to date have focused on a population of youth all of whom demonstrated a CUD.

Our own research group completed the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in adults with comorbid MDD and alcohol dependence (Cornelius, et al., 1997). That study demonstrated efficacy for fluoxetine in decreasing both the depressive symptoms and the alcohol use of profoundly depressed and suicidal adult depressed alcoholics. We then conducted a secondary analysis from that study involving the subsample of 22 subjects who used cannabis (Cornelius, et al., 1999). The results of that secondary analysis suggested efficacy for fluoxetine for decreasing the cannabis use of that population. A meta-analysis by Nunes & Levin (2004) found a pooled effect size of 0.38 in favor of antidepressant treatment for comorbid MDD/AUDSUD. That same meta-analysis also demonstrated that the placebo response rate accounted for more than 70% of the variation in effect sizes on depression outcome across studies.

We also recently completed a pilot study involving open label fluoxetine in adolescents with comorbid SUD and MDD. That pilot study demonstrated within-group efficacy for fluoxetine for decreasing both the cannabis use, the drinking, and the depressive symptoms of that population, and suggested that fluoxetine is a safe medication in that population (Cornelius, et al., 2005; Cornelius, et al., 2007). However, since no placebo group was involved in that pilot study, we cannot rule out the possibility that part or all of the therapeutic effect observed with fluoxetine was a placebo response. To date, no double-blind study of any SSRI medication has been conducted in adolescents and young adults with comorbid CUD/MDD.

In the current report, a prospective double-blind, placebo-controlled study is described involving an SSRI medication (fluoxetine) versus placebo in the treatment of adolescents and young adults with comorbid major depressive disorder and a cannabis use disorder (MDD/CUD). All subjects in both treatment groups also received 9 sessions of manual-based intensive therapy, which consisted of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Motivation Enhancement Therapy (MET). The primary goal of this study was to compare the acute phase (12 week) efficacy of the SSRI medication fluoxetine plus CBT and MET versus placebo plus CBT and MET therapy for the treatment of the depressive symptoms and the cannabis consumption of an adolescent and young adult sample with comorbid diagnoses of a cannabis use disorder (CUD) (cannabis dependence or cannabis abuse) plus major depressive disorder (MDD). We hypothesized that fluoxetine plus CBT/MET therapy would demonstrate efficacy versus placebo plus CBT/MET therapy for the treatment of both the depressive symptoms and the number of days of cannabis consumption of comorbid MDD/CUD adolescents.

2. Method

2.1. Subjects

Before entry into this treatment protocol, the study was explained, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (minors provided written assent and a parent provided written consent) after all procedures had been fully explained. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and was entered into the Clinical Trials Register (registration number NCT00149643). This study was conducted at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic (WPIC) of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). Subjects were recruited for participation in the treatment study through referrals from any of the WPIC treatment programs and by responding to newspaper, radio, and bus advertisements.

Study participants were required to be between 14 and 25 years of age at baseline to be included in the study. That age range was chosen because the prevalence of past-year cannabis dependence is higher among teenagers (2.6%) and young adults (3.5%) than among adults age 26 years or older (0.4%) (Dennis et al., 2002). At the baseline assessment, participants were evaluated for the DSM-IV diagnoses of a CUD and for MDD. The comorbid presence of both a current CUD and a current MDD was required for inclusion in the treatment study. Standardized diagnostic instruments were used to assess for current diagnoses of major depressive disorder and for cannabis abuse or dependence. The DSM-IV diagnosis of MDD was confirmed using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADSPL) (Kaufman, et al., 1997; Puig-Antich, 1986). The DSM-IV diagnosis of a cannabis use disorder (cannabis abuse or dependence) was confirmed using the Substance Use Disorders Section of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID) (First et al., 1997), which is an instrument that has also been validated for use with adolescents as well as adults (Martin, et al., 2000). Current cannabis use (use within the prior 30 days) was also required to be included in the study. In addition, a minimum current level of depressive symptoms was also required for study inclusion, as defined as a HAM-D-27 score of greater than or equal to 15 at the baseline assessment.

Exclusion criteria included a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophrenia. Subjects with hyper- or hypothyroidism, significant cardiac, neurological, or renal impairment, and those with significant liver disease (SGOT, SGPT, or gamma-GTP greater than 3 times normal levels) were also excluded from the study. Subjects who had received antipsychotic or antidepressant medication in the month prior to baseline assessment were excluded. Subjects with any substance abuse or dependence other than alcohol abuse or dependence, nicotine dependence, or cannabis abuse or dependence were excluded from the study. Subjects with any history of intravenous drug use were excluded from the study. Subjects were recruited into the study regardless of race, ethnicity, or gender. Other exclusion criteria were pregnancy, inability or unwillingness to use contraceptive methods, and an inability to read or understand study forms.

All subjects completed a comprehensive medical examination prior to entering the pharmacotherapy study. In addition, the medical health of all participants was assessed with standard laboratory tests, including CBC, differential blood count, electrolytes, SGOT, SGPT, gamma-GTP, TSH and an EKG. All female patients completed a urine pregnancy test prior to participation in the pharmacotherapy study. All participants completed a urine drug screen and a breathalyzer prior to participation in the pharmacotherapy study.

2.2 Treatment

Following completion of the baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine or placebo administered in identical-looking opaque capsules. Active medication and matching placebo were prepared by the research pharmacy at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Patient randomization was conducted by urn randomization, stratified by gender (Stout et al., 1994). All subjects were initially given 1 capsule (10 mg fluoxetine or placebo), which was increased after 2 weeks to 2 capsules (20 mg fluoxetine or placebo), which was the target dose of the study. The low dose of 10 mg as a starting dose was used in this study in order to maximize subject safety and to minimize the risk of medication side effects. Our dosage range was based on the findings of Riddle and colleagues (1991) and Jain and colleagues (1992), as well as with our own experience in our open label pilot study with comorbid adolescents (Cornelius et al., 2001). Drs. Cornelius, Bukstein, and Clark prescribed all protocol medications for patients participating in this study. The study was conducted in a double-blind fashion, though another study physician (Dr. Douaihy) remained non-blinded in order to handle any problems which may have arisen. Study visits occurred at nine time points: upon initiation of protocol medication (week 0), at the end of each of the first four weeks of the treatment trial (weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4), and on an everyother week basis during the final eight weeks of the study (weeks 6, 8, 10, and 12). Ratings of symptom severity occurred at each of those study visits. The higher frequency of visits during the first four weeks of the study was chosen in order to provide adequate monitoring during the first four weeks of the study when symptoms were most prominent and when medication side effects were most likely to occur.

The therapeutic interventions utilized in this study were chosen in an effort to provide effective treatment for both the depressive symptoms and the cannabis use of our comorbid population. Manual-based therapy was provided to all subjects in both treatment groups in this study. Therapy consisted of Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) for treatment of major depressive disorder and for treatment of the cannabis use disorder, and Motivation Enhancement Therapy (MET) for treatment of the cannabis use disorder. That therapy had been adapted by the study investigators (particularly O.G.B.) to be age appropriate for the study population. Both CBT and MET have previously demonstrated efficacy for treating cannabis dependence, as demonstrated in a series of randomized controlled trials (Elkashef et al., 2008; Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004; Stephens et al., 2000; Stephens et al., 1994). The therapy was provided during each protocol visit during the treatment trial, so participants received psychotherapy on nine occasions (weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12). Each of the 9 therapy sessions included therapy devoted to treatment of both the major depressive disorder and to the cannabis use disorder. The CBT for depression used in this study utilized the widely used techniques of cognitive therapy that have been adapted for treatment of adolescent depression, as described by Brent et al. (Brent, et al., 1997). This therapy was chosen because CBT has been reported to be more efficacious than alternative psychosocial interventions for the acute treatment of adolescents with MDD (Birmaher, et al., 2000). The CBT for treatment of CUD used in this study was modeled after the widely used techniques described in the CBT manual utilized in Project MATCH (Kadden, et al., 1994). The MET used in this study was adapted after the Motivation Enhancement Therapy used in Project MATCH (Miller, et al., 1992). All therapists in this study had obtained a master's degree in their field, had completed training courses in CBT and MET therapy, and had been providing therapy to comorbid adolescents and young adults for several years prior to their participation in this study. Thus, all therapists participating in this study were very experienced in their field, with particular expertise in conducting CBT and MET therapy with comorbid adolescents and young adults.

2.3 Assessment

Assessments for this study were completed by a Master's level staff member with several years of experience conducting assessments with comorbid adolescents. All assessors also completed a comprehensive clinical assessors training program, lasting between 2 and 3 months. All raters participating in the proposed treatment study must have demonstrated adequate levels of inter-rater reliability prior to administering ratings. Experiential training included observation of experienced assessors with independent coding of instruments (at least 5 sessions). Agreement with the interviewing clinician must have exceeded 90% for advancement to administering assessments with an assisting supervisor present. Prior to performing solo interviews, the assessor must have completed a minimum of two assessments with a supervisor present but not assisting, and coding must have achieved 90% agreement with the observing supervisor. After the completion of formal training, monitoring continues through periodic joint interview reliability evaluations with pairs of interviewers. Pill counts were used to ensure compliance with protocol medication. To ensure a high level of participation for these evaluations, a $20.00 payment was made to patients completing each assessment (Festinger, et al., 2008).

Subjects' diagnoses were finalized after case presentations at diagnostic conferences, attended by two study faculty members and the assessors. This “best estimate” diagnostic procedure (which is utilized for the SCID and SCID II as well as for the K-SADS) is in accordance with the method described by Leckman et al. (Leckman, et al., 1982), and was validated by Kosten & Rounsaville (1992). Observer-rated depressive symptoms were assessed with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D-27) (Hamilton, 1960). Participant-rated depressive symptoms were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, et al., 1961). Cannabis use behaviors and other substance use behaviors were assessed using the timeline follow-back method (TLFB) (Sobell LC, 1988). This instrument provided a daily tabulation of substance use behavior, thus providing detailed information on the quantity and frequency of this behavior. The primary cannabis use outcome variable was number of days of cannabis use. In addition, alcohol use outcome variables were assessed, including number of drinks per drinking day, the number of drinking days, and the number of heavy drinking days (defined as greater than or equal to 4 drinks per day for women and 5 for men). The Side Effects Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents was use to monitor side effects during each assessment throughout the course of the clinical trial (Klein and Slomkowski, 1993). Some information concerning the methods used in this study has been published elsewhere (Cornelius et al., 2008).

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Groups' continuous baseline measures were compared by independent, 2-tailed t tests for continuous variables. Groups' categorical baseline measures were compared by chi-square analysis, corrected for continuity. Statistical analyses were completed on an intent-to-treat study group basis. Outcome measures for depression and for cannabis use and alcohol use across treatment groups were compared by repeated measures analysis of variance. Repeated measure analysis ANOVA was chosen because of the low percentage of missing data in the study. The Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) method was used for handling missing data in the data analyses. All tests of significance were 2-tailed. An alpha level of less than or equal to 0.05 was used in the study. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 15.0 (Norusis, 1992).

3. Results

A total of 189 persons signed informed consent to participate in the acute phase study and completed the baseline assessment. Of those persons, 70 met all the inclusion criteria to participate in the Acute Phase Treatment Study, including 43 males and 27 females, all of whom were included in the outcome analyses. These participants included 39 Caucasians, 26 African-Americans, and 5 with mixed race. At recruitment, one subject was 15 years old, three subjects were 17 years old, 3 subjects were 18 years old, 13 subjects were 19 years old, and 11 subjects were 20 years old. Thus, a total of 31 subjects (44% of the subjects) were under the age of 21. The mean age of the study participants at recruitment was 21.1 +/− 2.4. years. The mean age of onset for cannabis abuse and for cannabis dependence were 16.7 +/− 2.1 and 16.8 +/− 2.2 respectively, while the mean age of onset of MDD was 17.9 +/− 3.6. Fifty-seven (81%) of the subjects were in their first episode of major depressive disorder, while the remaining 13 participants were in their second episode of MDD. Sixteen of the subjects reported a history of use of antidepressant medication prior to the month before recruitment. Use of antidepressant medication in the month immediately preceding recruitment occurred in no subjects, since use of antidepressant medication during the month before recruitment was an exclusionary criterion. Of the 189 persons who signed informed consent, 119 were excluded from participation in the study after a baseline assessment was conducted

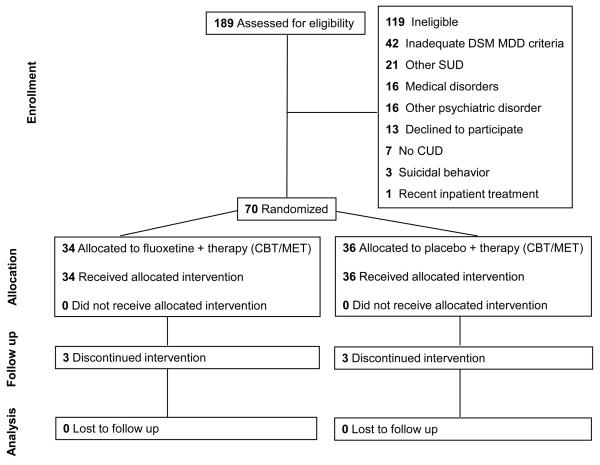

Most of these participants who entered the treatment trial (66/70, 94%) met DSM diagnostic criteria for cannabis dependence at baseline, and the other four subjects met diagnostic criteria for cannabis abuse. At baseline, the study subjects had been using cannabis an average of 76% of the days in the prior 30 days, meaning that frequent use of cannabis was the norm among the subjects in our study sample at baseline. Twenty of the subjects in the treatment trial also met diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence, and 7 met diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse, though in each of those cases the severity of the alcohol diagnosis was mild, and the cannabis use disorder was considered to be the primary substance use disorder. Sixteen of the subjects reported a history of use of an antidepressant medication prior to the most recent month, and none reported use of an antidepressant medication in the month prior to recruitment, which would have been an exclusion criterion. Subject flow information for study participants is provided in a CONSORT diagram in Figure 1. There were no significant differences between treatment groups on any baseline variables (Table 1).

Fig 1.

Consort diagram showing the flow of participants through each stage of the randomized trial.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Clinical Characteristics of Randomized Subjects

| Placebo (n=36) |

Fluoxetine (n=34) |

Placebo (n=36) |

Fluoxetine (n=34) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | Sig | |||||

| Sex (% female) | 36.1% | 41.2% | 0.424 | ||||||

| Ethnic (% white) | 58.3% | 55.9% | 0.836 | ||||||

| Placebo (n=36) |

Fluoxetine (n=34) |

Placebo (n=36) |

Fluoxetine (n=34) |

||||||

| Baseline | 12 Weeks (end of study) | ||||||||

| Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | Sig | |

| BDI Total | 16.64 | 9.85 | 18.06 | 8.80 | 7.31 | 8.29 | 7.79 | 7.98 | 0.803 |

| HAM-D 27 | 16.17 | 6.76 | 19.06 | 6.51 | 7.00 | 8.24 | 6.06 | 4.66 | 0.554 |

| DSM Cannabis Abuse Crit Count | 1.19 | 0.86 | 1.35 | 1.01 | 0.47 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.79 | 0.476 |

| DSM Cannab Depend Crit Count | 5.19 | 1.35 | 4.88 | 1.63 | 3.14 | 1.74 | 3.29 | 2.11 | 0.738 |

| DSM Cann Ab+Dep Crit count | 6.39 | 1.71 | 6.24 | 2.26 | 3.61 | 1.92 | 3.88 | 2.51 | 0.612 |

| DSM Alcohol Abuse Crit Count | 0.33 | 0.72 | 0.32 | 0.59 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.349 |

| DSM Alcohol Depend Crit Count | 1.00 | 1.43 | 1.24 | 1.62 | 0.75 | 1.20 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.678 |

| DSM Alco Ab+Dep Crit Count | 1.33 | 1.90 | 1.56 | 2.11 | 0.89 | 1.33 | 0.88 | 1.17 | 0.983 |

| DSM Current MDD Crit Count | 7.00 | 1.24 | 6.97 | 1.31 | 5.39 | 2.22 | 4.53 | 2.56 | 0.138 |

| Total Drinks per Week | 6.74 | 7.99 | 8.35 | 10.06 | 5.69 | 8.17 | 8.68 | 12.41 | 0.702 |

| Days of Alcohol Use per Week | 1.38 | 1.24 | 1.50 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 1.30 | 1.49 | 1.44 | 0.982 |

| Heavy Drinking Days per Week | 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 1.07 | 0.367 |

| Average drinks per drinking occasion in past month |

4.21 | 2.36 | 4.95 | 3.31 | 3.20 | 2.73 | 3.88 | 3.87 | 0.399 |

| Days used cannabis in past week | 4.35 | 1.93 | 4.61 | 2.18 | 3.10 | 2.27 | 3.88 | 2.60 | 0.182 |

Key: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; HAM-D 27, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 27-item version; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

During the course of the treatment trial, none of the subjects discontinued participation in the study because of medication side effects. No serious adverse events occurred during the course of the study. Subjects in the study tolerated the study medication (fluoxetine) very well. Side effects were rare and mild.

A reduction of self-reported and observer-reported depressive symptoms of greater than 50% was noted in both the fluoxetine group and the placebo group across the 12-week course of the clinical trial, as noted in Table 1. The majority of that improvement occurred during the first half of the clinical trial. Reductions in number of days of cannabis use were more modest, however, and that reduction was not statistically significant in either treatment group. However, a significant decrease of 39.5% was noted across the treatment groups in the number of DSM criteria for cannabis dependence during the course of the clinical trial, which was a significant improvement, though no significant difference between treatment groups was noted on that variable.

In repeated measure analysis of variance, no significant time by treatment group interactions were noted for any depressive outcome variables or any cannabis or other substance-related outcome variables (Table 2). However, a significant within-group improvement was noted for self-reported depressive symptoms (BDI), observer-rated depressive symptoms (HAMD 27), number of DSM cannabis dependence criteria, and number of DSM cannabis use disorder criteria (cannabis dependence criteria plus cannabis abuse criteria). Males drank more heavily than females throughout the course of the study, as shown by a significant main effect of gender in the number of days of alcohol use in the past month, the average number of drinks per drinking occasion in the past month, and the number of days of binging on alcohol (drinking more than or equal to 5 drinks per occasion), though no other significant main effects of gender were noted on other depression-related or substance-use related variables. A significant time by gender effect was noted on total BDI score and on DSM cannabis abuse criteria count, with females showing a greater improvement with time on those two variables than males, though no other significant time by gender effects were noted for any other variables.

Table 2.

Between – Group Comparisons of Treatment Outcome

| time | time x sex | time x treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | sig. | F | sig. | F | sig. | |

| BDI Total | 39.99 | <0.001 | 5.01 | 0.028 | 0.42 | 0.517 |

| HAM-D 27 | 30.69 | <0.001 | 1.74 | 0.192 | 0.35 | 0.559 |

| Days used alcohol in the past month |

0.01 | 0.933 | 0.14 | 0.714 | 0.10 | 0.748 |

| Total drinks in the past month |

0.32 | 0.571 | 0.06 | 0.813 | 0.00 | 0.955 |

| Average drinks per drinking occasion in past month |

1.28 | 0.261 | 0.51 | 0.479 | 0.05 | 0.826 |

| Days binge drinking (>/=5) in past month |

0.45 | 0.505 | 0.38 | 0.537 | 0.30 | 0.584 |

| Days used cannabis in past month |

1.40 | 0.242 | 0.17 | 0.685 | 1.26 | 0.265 |

| Days smoked cigarettes in past month |

1.38 | 0.245 | 0.42 | 0.520 | 0.35 | 0.558 |

| DSM AUD Total Count |

0.32 | 0.573 | 0.03 | 0.870 | 0.28 | 0.600 |

| DSM Cannabis Abuse Count |

0.02 | 0.884 | 4.22 | 0.044 | 0.10 | 0.753 |

| DSM Cannabis Dependence Count |

6.09 | 0.016 | 0.13 | 0.719 | 0.92 | 0.340 |

| DSM CUD Total Count (DSM dependence + abuse symptoms) |

4.65 | 0.035 | 0.17 | 0.683 | 0.50 | 0.481 |

| DSM Current MDD Symptom Count |

1.40 | 0.241 | 0.94 | 0.337 | 2.39 | 0.127 |

|

| ||||||

| sex | treatment | |||||

|

| ||||||

| F | sig. | F | sig. | |||

| BDI Total | 2.57 | 0.114 | 0.52 | 0.473 | ||

| HAM-D 27 | 0.16 | 0.686 | 0.17 | 0.683 | ||

| Days of alcohol use in the past month |

4.68 | 0.034 | 1.25 | 0.268 | ||

| Total drinks in the past month |

7.74 | 0.007 | 2.30 | 0.134 | ||

| Average drinks per drinking occasion in past month |

9.86 | 0.003 | 1.06 | 0.308 | ||

| Days used cannabis in past month |

2.83 | 0.097 | 1.13 | 0.292 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Days smoked cigarettes in past month |

0.26 | 0.609 | 0.10 | 0.748 | ||

| Days binge drinking (>/=5) in past month |

9.57 | 0.003 | 2.50 | 0.118 | ||

| DSM AUD Total Count |

1.80 | 0.184 | 0.16 | 0.690 | ||

| DSM Cannabis Abuse Count |

0.00 | 0.978 | 0.68 | 0.414 | ||

|

| ||||||

| DSM Cannabis Dependence Count |

0.01 | 0.916 | 0.06 | 0.811 | ||

|

| ||||||

| DSM CUD Total Count |

||||||

| (DSM depen/abuse symptoms) |

2.64 | 0.109 | 1.73 | 0.193 | ||

|

| ||||||

| DSM Current MDD Symptom Count |

2.64 | 0.109 | 1.73 | 0.193 | ||

Key: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; HAM-D 27, Hamilton Depress 27-item version; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

A total of 215 urine drug screens (UDS) were collected during the course of the study. The majority of study visits did not include UDS testing. Of those UDS collections, 170 were positive for cannabis (79%), which is consistent with the fact that most subjects continued to report cannabis use at some level throughout the course of the study. On only three occasions did a subject deny cannabis use in the previous two weeks while the UDS for cannabis was positive, suggesting a low rate of false negative reports.

4. Discussion

Fluoxetine was well tolerated in this study population. However, fluoxetine did not demonstrate greater efficacy than placebo for treating either the depressive symptoms or the cannabis-related symptoms of our study sample of comorbid adolescents and young adults. Specifically, no significant group-by-time interactions were noted for any depression-related or substance-related outcome variable. However, significant within-group improvement was noted for both measures of depressive symptoms across both treatment groups, accompanied by a greater than 50% reduction in depressive symptoms in both treatment groups. Also, a significant within-group improvement was noted across both treatment groups in number of DSM cannabis dependence criteria. End-of-study levels of depressive symptoms were low in both treatment groups, though decreases in number of days of cannabis use, level of alcohol use, and level of tobacco use during the study were more modest. The clinical improvement that was noted in both treatment groups may have resulted either from the CBT and MET therapy that the subjects received or may have reflected the natural course of their disorders. These findings are consistent with previous reports of a prominent “placebo” effect among adolescents (Klein, et al., 1998). The lack of a significant between-group difference in depressive symptoms or in level of substance use-related symptoms may reflect limited medication efficacy, spontaneous improvement, or efficacy of the CBT/MET psychotherapy, resulting in low levels of depressive symptoms at the end of the study in both treatment groups. It is also possible that a significant advantage to fluoxetine may have been detected with a larger sample size. However, it is noteworthy that there was not even a trend for a significant difference between groups was noted on any depressive measure or substance use variable, suggesting that having a larger sample size would probably not have changed the findings of the study.

The results of the current medication study can be compared to other recent trials of SSRI medications in comorbid adolescents and young adults. Riggs et al. (2007) conducted a clinical trial of fluoxetine versus placebo in adolescents with current MDD, lifetime conduct disorder, and at least one non-tobacco SUD. Riggs et al (2007) concluded that fluoxetine and CBT had greater efficacy than placebo and CBT on one but not both measures of depressive symptoms, and was not associated with greater decline in substance use. Specifically, fluoxetine demonstrated greater efficacy than placebo on the Childhood Depression Rating Scale, but not on the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement in Depressive Symptoms. Our own research group recently conducted a trial of fluoxetine versus placebo in a population of adolescents with comorbid major depressive disorder and an alcohol use disorder (Cornelius et al., 2009). The results of that study demonstrated no efficacy for fluoxetine for treating either the depressive symptoms or the alcohol use behaviors of that youthful comorbid population. However, a large improvement in depressive symptoms across both treatment groups was noted, with low end-of-trial levels of depressive symptoms, accompanied by more modest decreases in level of alcohol use, which suggested efficacy for the cognitive behavior therapy/motivation enhancement therapy used in that study. The results of the current study are also consistent with the results of a recent meta-analysis of antidepressant drug effects, which demonstrated minimal or non-existent benefit of antidepressant medication for persons with mild to moderate levels of depressive symptoms at baseline (Fournier, et al., 2010). The results of the current study, in conjunction with the results from the Riggs and colleagues (2007) study and the Cornelius et al., 2009 study suggest that psychological intervention, such as CBT/MET therapy, may be powerful therapies for comorbid youth. Those psychosocial therapies should probably be considered first-line treatment for this youthful comorbid population. The role of antidepressant medication in this population is unclear.

The lack of a significant medication effect noted in this study in combination with evidence of beneficial effects of the therapy raises questions regarding the optimal choice of behavioral therapy platforms for pharmacotherapy studies involving comorbid populations. Carroll and colleagues (1997; 2004) have noted that the selection of an appropriate behavioral platform for a particular trial requires study-specific tailoring, taking into account a number of factors, including comorbid problems. They have noted that the behavioral platform is intended to maximize medication adherence, to reduce protocol attrition, and to address ethical issues in placebo-controlled trials. However, it is possible for a powerful behavioral therapy platform to mask potential therapeutic medication effects. Therefore, it is also important to choose a behavioral therapy platform that maximizes study compliance and minimizes protocol attrition but still minimizes the likelihood of masking possible medication effects. Future pharmacotherapy studies involving comorbid populations should seek to balance the benefits versus the potential draw-backs of the specific behavioral therapy platform to be chosen.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, the sample in this study was limited to outpatient comorbid MDD/CUD adolescents and young adults. Consequently, it is unclear to what extent the results of this study generalize to the treatment of comorbid MDD/CUD adults or to comorbid adolescents and young adults in more intensive treatment settings, such as inpatient settings or partial hospital settings, where profound depressive symptoms are more common. Second, the period of observation in our trial was short in terms of the natural history of major depression and of cannabis use disorders. Continuation studies and long-term follow-up studies would be necessary to determine the long-term results of the treatments. Third, the sample size in the present study was limited. Large multi-site trials of selective serotonergic medications would be needed to more definitively evaluate the clinical utility of SSRI medications in subpopulations of comorbid MDD/CUD adolescents and young adults. For example, further studies would be needed to evaluate the efficacy of pharmacotherapy among populations with cannabis use disorders and psychiatric disorders that often co-occur with MDD, such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Cornelius et al., 2010). Further studies are also warranted involving psychosocial interventions among comorbid adolescents and young adults. Because of the limited efficacy of SSRI medications among comorbid populations to date, pharmacotherapy trials involving non-SSRI medications are also warranted among comorbid populations of adolescents and adults.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agosti V, Nunes E, Levin F. Rates of psychiatric comorbidity among U.S. residents with lifetime cannabis dependence. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:643–652. doi: 10.1081/ada-120015873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Kolko D, Baugher M, Bridge J, Holder D, Iyengar S, Uloa RE. Clinical outcome after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Holder D, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Roth C, Iyengar S, Johnson BA. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54:877–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM. Manual-guided psychosocial treatment: a new virtual requirement for pharmacotherapy trials. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54:923–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220041007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Choosing a behavioral therapy platform for pharmacotherapy of substance users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Marijuana use and the risk of major depressive episode: epidemiological evidence from the United States National Comorbidity Survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2002;37:199–206. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0541-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Bukstein OG, Birmaher B, Salloum IM, Lynch K, Pollock NK, Gershon S, Clark D. Fluoxetine in adolescents with major depression and an alcohol use disorder: an open-label trial. Addict. Behav. 2001;26:735–739. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Bukstein OG, Clark DB, Birmaher B, Salloum IM, Wood DS. Fluoxetine trial for the cannabis-related symptoms of comorbid adolescents. J. Drug Abuse, Educ., Eradic. 2007;3:223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Bukstein OG, Wood DS, Kirisci L, Douaihy A, Clark DB. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in adolescents with comorbid major depression and an alcohol use disorder. Addict. Behav. 2009;34:905–909. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Chung T, Martin C, Wood DS, Clark DB. Cannabis withdrawal is common among treatment-seeking adolescents with cannabis dependence and major depression, and is associated with rapid relapse to dependence. Addict. Behav. 2008;33:1500–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Clark DB, Bukstein OG, Birmaher B, Salloum IM, Brown SA. Acute phase and five-year follow-up study of fluoxetine in adolescents with major depression and a comorbid substance use disorder: a review. Addict. Behav. 2005;30:1824–1833. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Clark DB, Hayes J, Tarter R. PTSD contributes to teen and young adult cannabis use disorders. Addict. Behav. 2010;35:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Ehler JG, Jarrett PJ, Cornelius MD, Perel JM, Thase ME, Black A. Fluoxetine in depressed alcoholics: A double-blind, placebo- controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54:700–705. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Haskett RF, Ehler JG, Jarrett PJ, Thase ME, Perel JM. Fluoxetine versus placebo for the marijuana use of depressed alcoholics. Addict. Behav. 1999;24:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Babor T, Roebuck MC, Donaldson J. Changing the focus: the case for recognizing and treating marijuana use disorders. Addiction. 2002;97(Suppl.1):S4–S15. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkashef A, Vocci F, Huestis M, Haney M, Budney A, Gruber A, el-Guebaly N. Marijuana neurobiology and treatment. J. Subst. Abuse. 2008;29:17–29. doi: 10.1080/08897070802218166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie GJ, Heiligenstein JH, Wagner KD, Hoog SL, Ernest DE, Brown E, Neilsson M, Jacobson JG. Fluoxetine for acute treatment of depression in children and adolescents: A placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2002;4:1205–1215. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie GJ, Kennard BD, Mayes TL, Nightingale-Teresi J, Carmody T, Hughes CW, Rush AJ, Tao R, Rintelmann JW. Fluoxetine versus placebo in preventing relapse of major depression in children and adolescents. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:459–67. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, Weinberg WA, Kowatch RA, Hughes CW, Carmody T, Rintelmann J. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54:1031–1037. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230069010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Marlowe DB, Dugosh KL, Croft JR, Arabia PL. Higher magnitude cash payments improve research follow-up rates without increasing drug use or perceived coercion. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) Biometrics Research, New York Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurology Neurosurg, Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain U, Birmaher B, Garcia M, Al-Shabbout M, Ryan N. Fluoxetine in children and adolescents with mood disorders: A chart review of efficacy and adverse events. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 1992;2:259–265. doi: 10.1089/cap.1992.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadden R, Carroll KM, Donovan D, Cooney N, Monti P, Abrams D, Litt M, Hester R. Cognitive-behavioral coping skills therapy manual: A clinical Research Guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Vol. 5. NIAAA; Rockville, MD: 1994. (Project MATCH Monograph Series). (DHHS Publication No. 96-4004). [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Koplewicz HS, Tancer NK, Shah M, Liang V, Davies M. Adolescent depression: controlled desipramine treatment and atypical features. Depression Anxiety. 1998;7:15–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<15::aid-da3>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Rounsaville BJ. Sensitivity of psychiatric diagnosis based on the best estimate procedure. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1992;149:1225–1227. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson WD, Belanger A, Weissman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodological study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1982;39:879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Silva SG, Compton S, Anthony G, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Califf R, Krishnan R. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network (CAPTN) J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2004;43:515–518. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: findings from a randomized multisite trial. J Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:455–466. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Pollock NK, Bukstein OG, Lynch KG. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID alcohol and substance use disorders section among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Motivational Enhancement Therapy Manual. Vol. 2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Washington, DC: 1992. (Project MATCH Monograph Series). [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom BR, Levin FR. Treatment of cannabis use disorders: A review of the literature. Am. J. Addictions. 2007;16:331–342. doi: 10.1080/10550490701525665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norusis MJ. Norusis Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. McGraw –Hill; New York, USA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Levin FB. Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:1887–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J. Biological factors in prepubertal major depression. Pediatr. Annals. 1986;15:867, 870–2. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19861201-09. 873-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: Results from the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle MA, King RA, Hardin MT, Scahill L, Ort SI, Chappell P, Rasmusson A, Leckman JF. Behavioral side effects of fluoxetine in children and adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 1991;1:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs PD, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Davies RD, Lohman M, Klein C, Stover SK. A randomized controlled trial of fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents with major depression, behavior problems, and substance use disorders. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007;161:1026–1034. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback. In: Rush AJ, First MB, Blacker D, editors. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Second Edition American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Washington, DC: 2008. pp. 466–468. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers' reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br. J. Addict. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Simpson EE. Treating adult marijuana dependence: a test of the relapse prevention model. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1994;62:92–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Saha T. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug abuse disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;80:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Pickering R, Grant BF. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychol. Med. 2006;36:1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;(Suppl 12):70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): Long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132–1144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]