Abstract

Background

Adjustment to chronic disease is a multidimensional construct described as successful adaptation to disease-specific demands, preservation of psychological well-being, functional status, and quality of life. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can be particularly challenging due to the unpredictable, relapsing and remitting course of the disease.

Methods

All participants were patients being treated in an outpatient gastroenterology clinic at a university medical center. Participants completed a survey of questionnaires assessing illness perceptions, stress, emotional functioning, disease acceptance, coping, disease impact, and disease-specific and health-related quality of life. Adjustment was measured as a composite of perceived disability, psychological functioning, and disease-specific and health-related quality of life.

Results

Participants were 38 adults with a diagnosis of either Crohn’s disease (45%) or ulcerative colitis (55%). We observed that our defined adjustment variables were strongly correlated with disease characteristics (r = 0.33–0.80, all P < 0.05), an emotional representation of illness (r = 0.44–0.58, P < 0.01), disease acceptance (r = 0.34–0.74, P < 0.05), coping (r = 0.33–0.60, P < 0.05), and frequency of gastroenterologist visits (r = 0.39–0.70, P < 0.05). Better adjustment was associated with greater bowel and systemic health, increased activities engagement and symptom tolerance, less pain, less perceived stress, and fewer gastroenterologist visits. All adjustment variables were highly correlated (r = 0.40–0.84, P < 0.05) and demonstrated a cohesive composite.

Conclusions

The framework presented and results of this study underscore the importance of considering complementary pathways of disease management including cognitive, emotional, and behavioral factors beyond the traditional medical and psychological (depression and anxiety) components.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, adjustment, disease acceptance, disability, health-related quality of life

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, relapsing and remitting autoimmune disease that includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). The prevalence of IBD is estimated at 396 cases per 100,000 worldwide, affecting up to 1.4 million people in the U.S.1 Current standard of care in IBD treatment is aimed at managing the inflammatory response during flare episodes and maintaining remission with an emphasis on adhering to a regular medication regimen.2 It is known that individuals with chronic disease experience alterations in quality of life and functioning in the physical, psychological, social, and occupational realms. For people with IBD, quality of life is compromised,3–10 and has been shown to be correlated with factors such as psychological distress,3–7 social support,4,6 and coping.3,6,10

Most experts will agree that when patients receive a new diagnosis of IBD, a natural psychological adaptation response occurs in a relatively short period of time. For example, a common reaction to a new diagnosis of IBD might include: an initial evaluation of the disease’s impact on life activity and plans; an emotional response including relief, distress, grief, and guilt; and a behavioral response that may include taking new medications, seeking social support, modifying diet, and managing stress. This adaptation, or adjustment, is a complex and dynamic process likely influenced by age of onset of disease, disease severity, the scope of interference in life and future plans, core beliefs about health and illness, illness attributions, emotional state, learned behaviors, and disease-related demands. After the initial adaptation to the diagnosis occurs, patients may experience ongoing adjustment challenges given the chronic and often unpredictable course of IBD. Throughout the adjustment process, patients may feel frustrated, sad, develop fears, miss work, and avoid social events and traveling due to the relapsing and remitting course of IBD. Moreover, physicians and patients often express an interest in more comprehensive treatment options that address both medical and psychological aspects of IBD.

Psychological adjustment to chronic disease has been an important focus in the areas of cardiovascular disease, cancer, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid diseases. Stanton et al11 identify 5 indicators of adjustment to chronic illness including: mastery of disease-related adaptive tasks, preservation of functional status, absence of psychological disorder, low negative affect, and preservation of quality of life. Investigating psychological adjustment to IBD is important because it may help to further explain patient-reported outcomes in IBD.

The aims of this study were 3-fold: 1) to identify sensitive and specific measures of adjustment to IBD including functional status, psychological functioning, and health-related quality of life; 2) to examine the relationship of such constructs to disease characteristics, illness and stress perceptions, disease acceptance, coping, healthcare utilization, and missed work; and 3) to provide preliminary evidence supporting a framework of adjustment to IBD on which future research can be built. We hypothesized that we would observe statistically significant correlations across adjustment variables and disease characteristics, illness and stress perceptions, disease acceptance, coping, healthcare utilization, and missed work.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

For this study we used a cross-sectional research design. Participants were recruited from a behavioral health clinic that is part of an interdisciplinary outpatient gastroenterology clinic at a university medical center. After obtaining informed consent, all participants completed a set of questionnaires and underwent a brief clinical interview with a postdoctoral fellow in behavioral medicine (J.L.K.), a specialty area within clinical psychology.

Participants

Our total sample includes 38 adults with IBD. Inclusion criteria included male and female patients over 18 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of either CD or UC.

Measures

Disease Severity and Health-related Quality of Life (HRQOL)

The IBD Quality of Life (IBDQ)12–14 is a validated 32-item measure of disease activity and HRQOL related to IBD specifically. Domains measured include systemic symptoms, bowel symptoms, social factors, and emotional functioning. Participants are asked to respond to each question using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “worst” to 7 “best.” Scores range from 32 to 224, with higher scores representing better perceived health and functioning. This questionnaire is commonly used in clinical trials as a primary clinical endpoint and demonstrates excellent reliability and validity.

The Short Form 12v2 Health Survey (SF-12v2)15 is a 12-item, general purpose, HRQOL measure that includes a simple measure of overall perceived health. This measure is a shorter version of the commonly used SF-36.16 The SF-12 yields 2 quality of life factors, the physical health summary score (PCS) and a mental health summary score (MCS). Higher scores indicate better perceived health and functioning. The scores are comparable to the PCS and MCS scale on the SF-36 and are highly reliable and valid across several health conditions.15

Psychological Functioning

Psychological functioning can be measured in a multitude of ways including questionnaires asking about thoughts and beliefs (i.e., cognitions), emotional distress, and behaviors (e.g., disease acceptance and healthcare utilization). First, we measured cognitions related to illness using 2 measures: Illness Perceptions Questionnaire – Revised (IPQ-R)17 and Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ).18 Second, we measured emotional distress using a single questionnaire, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI).19 And third, we assessed health-related behaviors in 3 ways: Digestive Diseases Acceptance Questionnaire (DDAQ),20 healthcare utilization, and Brief Cope.21

The IPQ-R17 is a 38-item measure assessing multiple domains of illness perceptions by the individual. The formation of illness perceptions help to create a framework for making sense of their symptoms, assessing health risks, and directing action and coping. Components of illness measured by the IPQ-R include identity (i.e., diagnosis and symptoms), cause of illness, chronicity of illness, impact on life, and beliefs about control over illness. For the purposes of this study, we used components including the chronicity of illness, impact on life, and beliefs about control over illness. Internal consistency and test–retest reliability is adequate with demonstrated discriminant validity across different disease classes.

The PSQ18 is a validated general-purpose 30-item measure of perceived stress with established norms for patients with IBD. Internal consistency and test–retest reliability are adequate and the measure has demonstrated concurrent validity with anxiety, other measures of perceived stress, depression, and somatization. The PSQ has been successful in predicting health outcomes, psychological distress, and inflammation in IBDs. The measure provides an evaluation of stress across 7 domains: harassment, overload, irritability, lack of joy, fatigue, worries, and tension. Higher scores indicate greater perceived stress.

The BSI19 is a validated 18-item questionnaire to assess overall psychological distress (including depression, anxiety, and somatization), symptom intensity, and total number of symptoms reported. Items on the BSI are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 “not-at-all” to 4 “extremely.” Scores range from 0–72; higher scores indicate higher levels of distress. The BSI-18 has good internal reliability and test–retest reliability.

The DDAQ20 is a 20-item disease acceptance questionnaire asking about symptom tolerance and active behavioral engagement in daily life activities despite digestive symptoms. Items on the DDAQ are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 “never true” to 6 “always true.” Scores range from 0–120 with higher scores indicating greater disease acceptance. The original acceptance questionnaire containing 34 items (CPAQ) was developed and validated in chronic pain22 and has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity.22,23

Healthcare utilization variables included the frequencies of number of visits to one’s physician related to gastrointestinal symptoms (either primary care or gastroenterologist) in the past year, total number of hospitalizations due to gastrointestinal condition, and total number of surgeries specific to gastrointestinal condition. Missed work was assessed by asking participants whether they missed any work due to their gastrointestinal condition in addition to the average number of days missed per month in the past year.

The Brief Cope21 is a validated 28-item questionnaire to assess coping behaviors known to be effective and ineffective strategies. There are 14 subscales with 2 items each; response options range from 0 “not at all” to 3 “a lot or all of the time” per item. Internal consistency across subscales is good and factor analysis revealed a 9-factor structure explaining 72.4% of the variance observed. The author recommends that this scale not be summed to indicate an overall score, but rather use the subscales to indicate a preference for particular coping strategies, which can be characterized by either effective or less effective.

Functional Status

The Perceived Disability Scale (PDS)24 is a 10-item questionnaire designed to assess perceived limitations and disability in multiple domains of daily functioning (e.g., social, occupational, recreation, self-care, physical, and sexual). The participant rates the level of disability per domain on an 11-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 “no disability” to 10 “total disability.” Total scores range from 0–100; higher scores indicate more perceived disability. This measure was originally validated in a chronic pain population.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Information

We used a standard demographic and disease history questionnaire to obtain data from study participants on age, gender, race, marital status, educational attainment, diagnosis, pain intensity, length of time since diagnosis, remission status, medication regimen, height, weight, and impact of disease.

Statistical Analysis

For the novel measures used in this study (DDAQ and PDS), we evaluated internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha to estimate average interitem correlation. To assess the linear relationship among variables we used the Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient. In the case that we wanted to test the differences in means of continuous variables between CD versus UC and flare versus remission, we used the independent samples t-test. Also, we tested for differences between our observed scale scores and those reported in the literature on a few measures using the 1-sample t-test.

Ethical Considerations

Individually identifiable data were removed to ensure participants’ privacy. The study was reviewed and approved by Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board for the protection of human subjects participating in research.

RESULTS

In our sample (N = 38), 55% had UC, 63% were women, 82% were white, 55% were single (never married), 42% had a college degree and 32% had a Master’s degree, 24% reported past bowel resections, 55% reported missing work due to IBD in the past year (with mean days missed per month = 2.1, range 1–22 days), and 61% reported being in remission at the time of participation. Their mean age was 36.2 (range 22–68 years), mean body mass index (BMI) of 26.4 (range 18.8–53.7), and mean length of time since diagnosis (LOTD) was 10 years (range 0.2–53.3 years). Within the IBD group, there were 2 significant differences between those individuals with CD and those with UC on clinical characteristics: those with CD reported more bowel surgeries (χ2 (1) = 4.852, P = 0.03) and more hospitalizations (t (36) = −2.386, P = 0.03). Clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Significant differences were observed between those respondents reporting being in flare versus those in remission and include: abdominal pain, total score on the IBDQ, bowel health, social and emotional functioning, perceived stress, sense of personal control over illness, perceived disability, emotional distress, and physical functioning (all P ≤ 0.05). See Table 2 for illustration.

TABLE 1.

Age, Disease, Health Behavior, and Psychological Characteristics of the Total Sample (N=38)

| Variables | Median (25–75 Percentile) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 33.5 (29.0–39.3) | 36.2 (11.2) | 22–68 |

| Disease duration (in years) | 7.0 (2.1–16.3) | 10.0 (10.8) | 0.2–53 |

| Abdominal Pain Severity | 0 (0–2.0) | 1.2 (2.0) | 0–7 |

| IBDQ scores - Total | 175.5 (150.5–187.8) | 165.7 (33.2) | 77–218 |

| Bowel | 57.5 (48.8–62.3) | 54.0 (11.5) | 29–68 |

| Systemic | 23.0 (18.5–27.0) | 22.2 (6.2) | 7–33 |

| Social | 31.0 (26.8–35.0) | 29.9 (5.5) | 14–35 |

| Emotional | 62.5 (48.8–70.3) | 59.6 (14.5) | 20–82 |

| Perceived Disability Scalea | 12.0 (3.0–28.5) | 17.3 (18.1) | 0–77 |

| Body Mass Index | 25.0 (22.1–28.4) | 26.4 (6.8) | 18–54 |

| Health care utilization | |||

| Physician visitsb | 3.0 (2.0–5.3) | 4.8 (4.9) | 0–25 |

| Hospitalizationsa | 1.0 (0–3.0) | 2.2 (0.4) | 0–15 |

| History of surgeriesa | 0 (0–0.5) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0–1 |

| Missed workb | 0.1 (0–2.0) | 2.1 (4.6) | 0–22 |

| Perceived Stress Questionnaire | 66.0 (58.0–79.5) | 69.3 (16.7) | 40–116 |

| IPQR | |||

| Chronicity | 25.0 (19.5–28.0) | 23.7 (5.0) | 12–30 |

| Personal control | 23.0 (18.5–24.0) | 21.8 (4.1) | 14–30 |

| Treatment control | 18.0 (14.5–20.0) | 17.8 (4.0) | 6–25 |

| Illness coherence | 18.0 (13.5–21.0) | 17.2 (4.7) | 6–25 |

| Cyclical nature | 14.0 (13.0–16.0) | 14.2 (2.8) | 5–25 |

| Emotional | 20.0 (15.0–24.0) | 19.0 (5.2) | 7–29 |

| Consequence | 21.0 (16.5–24.0) | 20.0 (5.1) | 8–29 |

| Digestive Diseases Acceptance Qst | |||

| Activities engagement | 43.0 (37.0–50.0) | 42.9 (9.7) | 22–60 |

| Symptom tolerance | 29.0 (22.5–36.0) | 28.7 (9.4) | 12–48 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory | 7.0 (2.5–11.5) | 9.8 (10.6) | 0–53 |

| SF-12v2 | |||

| Physical Component Summary | 51.3 (47.8–53.8) | 50.6 (6.1) | 32–65 |

| Mental Component Summary | 42.0 (33.1–51.1) | 41.7 (11.1) | 14–60 |

IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; IPQR, Illness Perceptions Questionnaire Revised; SF-12v2; Short Form Health Survey Version 2.

Related to GI symptoms only.

Related to GI symptoms in the past year.

TABLE 2.

Disease, Health Behavior, and Psychological Characteristics by Disease State (N=37)

| Variables | Flare (n=14) | Remission (n=23) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Disease duration (in years) | 13.8 (15.1) | 7.8 (6.5) | — |

| Abdominal pain severity | 2.6 (2.6) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.001 |

| IBDQ scores - Total | 147.6 (37.7) | 175.7 (26.1) | 0.01 |

| Bowel | 46.9 (11.7) | 58.0 (9.5) | 0.003 |

| Systemic | 20.6 (6.5) | 23.3 (6.0) | — |

| Social | 27.1 (6.4) | 31.3 (4.2) | 0.02 |

| Emotional | 53.0 (16.9) | 63.2 (11.9) | 0.04 |

| Perceived Disability Scalea | 25.6 (23.3) | 12.3 (12.1) | 0.03 |

| Body Mass Index | 28.6 (9.0) | 24.9 (4.8) | — |

| Health care utilization | |||

| Physician visitsb | 5.6 (5.9) | 4.4 (4.4) | — |

| Hospitalizationsa | 2.4 (4.2) | 2.2 (2.8) | — |

| History of surgeriesa | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.4) | — |

| Missed workb | 3.8 (6.9) | 1.1 (1.9) | — |

| Perceived Stress Questionnaire | 76.1 (18.7) | 65.1 (14.3) | 0.05 |

| IPQR | |||

| Chronicity | 25.2 (4.9) | 22.6 (5.0) | — |

| Personal control | 19.8 (3.5) | 23.0 (4.2) | 0.03 |

| Treatment control | 16.4 (4.5) | 18.8 (3.5) | — |

| Illness coherence | 16.4 (4.7) | 18.1 (4.7) | — |

| Cyclical nature | 14.1 (3.6) | 14.1 (2.3) | — |

| Emotional | 20.3 (5.4) | 18.0 (5.1) | — |

| Consequence | 19.6 (5.3) | 20.3 (5.1) | — |

| Digestive Diseases Acceptance Qst | |||

| Activities engagement | 43.0 (12.7) | 42.9 (7.7) | — |

| Symptom tolerance | 30.4 (8.3) | 27.7 (10.0) | — |

| Brief Symptom Inventory | 16.1 (13.7) | 6.0 (5.8) | 0.004 |

| SF-12v2 | |||

| Physical Component Summary | 47.8 (8.2) | 52.3 (3.5) | 0.03 |

| Mental Component Summary | 38.8 (12.6) | 43.5 (9.9) | — |

SD, standard deviation; IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; IPQR, Illness Perceptions Questionnaire Revised; SF-12v2, Short Form Health Survey Version 2.

Statistically significant difference.

Related to GI symptoms only.

Related to GI symptoms in the past year.

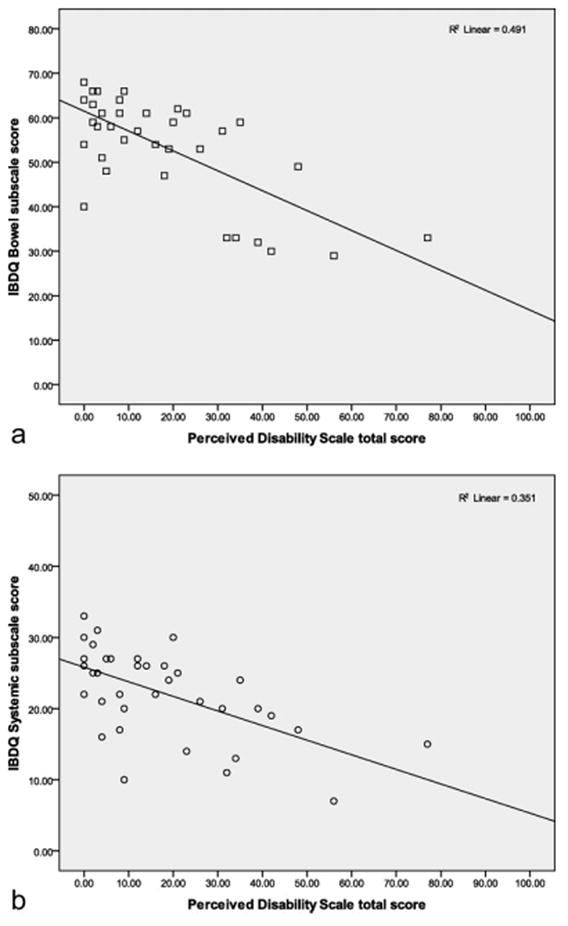

Table 3 shows the associations between the adjustment variables and disease characteristics, stress and illness perceptions, disease acceptance, missed work, and health-care utilization. Statistically significant correlations were observed across multiple bivariate comparisons. Notably, adjustment variables were strongly correlated with disease characteristics, perceived stress, an emotional representation of illness, disease acceptance, frequency of visits to a gastroenterologist, and missed work. As a measure of functional status, scores on the PDS were negatively correlated with scores of bowel and systemic health on the IBDQ (see Fig. 1 for illustration) and activities engagement on the DDAQ, while positively correlated with pain severity, perceived stress, and gastroenterologist visits.

TABLE 3.

Bivariate Correlations Grouped by Adjustment Variables and Disease Characteristics, Perceived Stress, Illness Perceptions, Disease Acceptance, Health Care Utilization, and Missed Work (N=38)

| Variables | Adjustment |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDS | BSI | IBDQ Social | IBDQ Emotional | SF-12v2 PCS | SF-12v2 MCS | |

| Disease duration | −0.1 | −0.11 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| IBDQ | ||||||

| Bowel health | −0.70** | −0.56** | 0.80** | 0.71** | 0.64** | 0.44** |

| Systemic health | −0.59** | −0.56** | 0.41* | 0.72** | 0.52** | 0.67** |

| Abdominal pain severity | 0.59** | 0.58** | −0.63** | −0.58** | −0.59** | −0.33* |

| Perceived stress | 0.43** | 0.74** | −0.25 | −0.75** | −0.06 | −0.83** |

| IPQR | ||||||

| Timeline - chronicity | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0 |

| Personal control | −0.13 | −0.06 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0 | −0.03 |

| Treatment control | −0.16 | −0.24 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.2 |

| Illness coherence | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.12 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.16 |

| Cyclical nature | 0.14 | −0.04 | −0.22 | −0.04 | −0.17 | 0.11 |

| Emotional representation | 0.4 | 0.56** | −0.44** | −0.58** | −0.26 | −0.56** |

| Consequence | 0.24 | 0.29 | −0.32a | −0.40* | −0.11 | −0.38* |

| Disease acceptance | ||||||

| Activities engagement | −0.42* | −0.64** | 0.47* | 0.74* | 0.31 | 0.69** |

| Symptom tolerance | −0.23 | −0.3 | 0.42* | 0.40* | 0.29 | 0.34* |

| Health care utilization | ||||||

| Physician visits | 0.39* | 0.70** | −0.40* | −0.58** | −0.07 | −0.47** |

| Hospitalizations | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.01 |

| History of surgeries | 0.33 | 0.03 | −0.31 | −0.11 | −0.21 | 0.03 |

| Missed work | 0.29 | 0.26 | −0.63** | −0.35a | −0.54** | −0.23 |

PDS, Perceived Disability Scale; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; SF-12v2, Short Form Health Survey Version 2; PCS, Physical Component Summary; MCS, Mental Component Summary; IPQR, Illness Perceptions Questionnaire-Revised.

P < 0.01,

P < 0.05.

Coefficient approaching significance, P = 0.05.

FIGURE 1.

Inverse correlation between bowel and systemic health indices of the IBDQ and the PDS, R2 = 0.49, 0.35. This figure demonstrates that higher IBDQ scores are associated with lower perceived disability.

Scores on the BSI were negatively correlated with bowel health, systemic health, and activities engagement, while positively correlated with pain severity, perceived stress, emotional representation on the IPQR, and physician visits. Scores on the social and emotional functioning subscales of the IBDQ were negatively correlated with pain severity, emotional representation of illness, and gastroenterologist visits, while positively correlated with bowel and systemic health, activities engagement, and symptom tolerance of the DDAQ. Moreover, scores on emotional functioning were negatively correlated with perceived stress.

As a general measure of HRQOL, the scores on the SF-12v2 were positively correlated with scores of bowel and systemic health, activities engagement, and symptom tolerance. In contrast, SF-12v2 scores were negatively correlated with pain severity, perceived stress (MCS only), emotional representation and consequence of illness (MCS only), gastroenterology visits (MCS only), and missed work (PCS only).

On the Brief Cope, all participants endorsed using a multitude of coping strategies related to IBD. Each of the 38 cases was tallied to identify primary coping strategies by high score on a subscale (with categories not mutually exclusive). The majority of the sample (79%) endorsed using acceptance most/all of the time as a primary coping strategy, followed by seeking emotional support (45%), active coping (42%), cognitive reframing (37%), planning (34%), and religion (34%). While the least often reported coping strategies included the use of denial, substance use, disengagement, self-blame, venting, humor, self-distraction, and instrumental support (all less than 30%).

The coping subscales of the Brief Cope were significantly correlated with adjustment variables. Higher scores on the BSI and the PDS were positively related to the use of substances (r = 0.47, 0.41, P ≤ 0.01), venting (r = 0.58, 0.34, P < 0.05), and self-blame (r = 0.61, 0.46, P < 0.01). Scores on social and emotional functioning of the IBDQ were negatively correlated with substance use (r = −0.39, −0.44, P ≤ 0.01), venting (r = −0.44, −0.60, P < 0.01), self-blame (r = −0.41, −0.51, P ≤ 0.01), and self-distraction (r = −0.38, −0.33, P < 0.05). Higher scores on the physical component of the SF12v2 were negatively associated with venting (r = −0.35, P < 0.05) and self-distraction (r = −0.42, P = 0.01), while scores on the mental component were negatively associated with venting (r = −0.53, P < 0.01), self-blame (r = −0.57, P < 0.01), and substance use (r = −0.34, P < 0.05).

Table 4 shows the associations across all adjustment variables: perceived disability, emotional distress, social and emotional functioning, and HRQOL. Overall, these correlations were statistically significant with coefficients ranging from 0.40–0.84.

TABLE 4.

Bivariate Correlations Across Adjustment Variables Including Functional Status, Emotional and Social Functioning, and Health-Related Quality of Life for the IBD Sample (N=38)

| Adjustment Variables | PDS | BSI | IBDQ Social | IBDQ Emotional | SF-12v2 PCS | SF-12v2 MCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDS | 1.00 | |||||

| BSI | 0.50** | 1.00 | ||||

| IBDQ Social | −0.81** | −0.45** | 1.00 | |||

| IBDQ Emotional | −0.71** | −0.79** | 0.69** | 1.00 | ||

| SF-12v2 PCS | −0.62** | −0.21 | 0.74** | 0.50** | 1.00 | |

| SF-12v2 MCS | −0.50** | −0.73** | 0.40* | 0.84** | 0.21 | 1.00 |

IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; SF-12v2, Short Form Health Survey Version 2; PDS, Perceived Disability Scale; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; PCS, Physical Component Summary; MCS, Mental Component Summary.

P < 0.01;

P < 0.05.

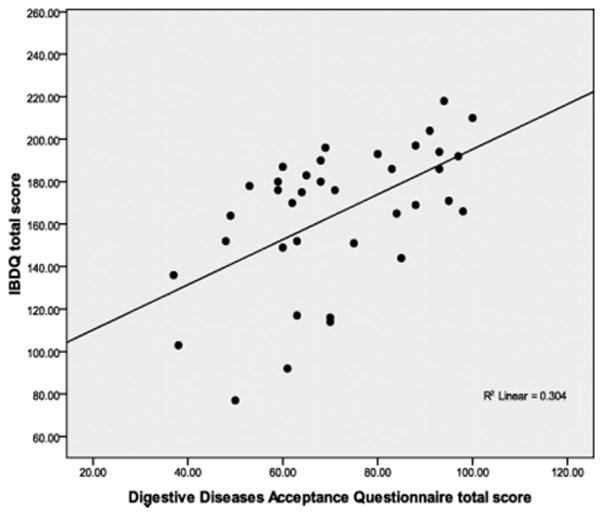

In this study we used 2 novel measures, the PDS and DDAQ that have not yet been validated within a digestive diseases population. The internal consistency estimates for the 2 measures were: PDS (α = 0.92) and DDAQ (α = 0.88). The subscale of the DDAQ can be interpreted in 2 parts and the internal consistency of each subscale is: activities engagement (α = 0.84) and symptom tolerance (α = 0.80). Perceived disability was significantly negatively correlated with bowel and systemic health indices on the IBDQ (r = −0.70, −0.59, P < 0.01); see Figure 1 for linear illustration. The DDAQ total score was significantly correlated with the total score on the IBDQ (r = 0.55, P < 0.01) and subscale scores’ correlations are listed in Table 5; also, see Figure 2 for linear illustration.

TABLE 5.

Bivariate Correlations Grouped by Disease Acceptance, Adjustment Variables, Disease Characteristics, Perceived Stress, Illness Perceptions, Health Care Utilization, and Missed Work (N=38)

| Variables | Digestive Diseases Acceptance Questionnaire Subscales |

|

|---|---|---|

| Activities Engagement | Symptom Tolerance | |

| Perceived Disability Scale | −0.42* | −0.23 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory | −0.64** | −0.30 |

| IBDQ: Social functioning | 0.47** | 0.42* |

| IBDQ: Emotional functioning | 0.74** | 0.48** |

| SF12v2: Physical Component Summary | 0.31 | 0.29 |

| SF12v2: Mental Component Summary | 0.69** | 0.34* |

| Disease duration (in years) | 0.37* | 0.23 |

| IBDQ: Bowel health | 0.35* | 0.21 |

| IBDQ: Systemic health | 0.46** | 0.23 |

| Abdominal pain severity | −0.34* | −0.21 |

| Perceived stress | −0.61** | −0.20 |

| IPQR: Timeline – chronicity | 0.09 | −0.02 |

| IPQR: Personal control | −0.08 | −0.06 |

| IPQR: Treatment control | 0.17 | 0.10 |

| IPQR: Illness coherence | −0.12 | 0.15 |

| IPQR: Cyclical nature | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| IPQR: Emotional representation | −0.52** | −0.71** |

| IPQR: Consequence | −0.51** | −0.70** |

| Physician visits | −0.48** | −0.41* |

| Hospitalizations | 0.09 | −0.25 |

| History of surgeries | 0.26 | 0.00 |

| Missed work | −0.53** | −0.42* |

IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; SF-12v2, Short Form Health Survey Version 2; IPQR, Illness Perceptions Questionnaire-Revised.

P < 0.01,

P < 0.05.

FIGURE 2.

Positive correlation between total scores on the IBDQ and the DDAQ. This figure demonstrates higher IBDQ total scores are associated with disease acceptance.

DISCUSSION

The aims of this study were 3-fold: 1) to identify sensitive and specific measures of adjustment to IBD including functional status, psychological functioning, and HRQOL; 2) to examine the relationship of such constructs to disease characteristics, illness and stress perceptions, disease acceptance, coping, healthcare utilization, and missed work; and 3) to provide preliminary evidence supporting a framework of adjustment to IBD on which future research can be built. We hypothesized that we would observe statistically significant correlations across adjustment variables and disease characteristics, illness and stress perceptions, disease acceptance, coping, healthcare utilization, and missed work. Consistent with our proposed framework and hypotheses, the current study supports the notion that adjustment in IBD includes a complex, dynamic interplay of clinical variables (disease characteristics, stress, illness perceptions, healthcare utilization, and disease acceptance) and outcome variables indicative of adjustment (disability, psychological functioning, and HRQOL).

Perceived disability was associated with bowel and systemic health deficits, more abdominal pain, less activities engagement, higher perceived stress, and greater number of gastroenterologist visits. Psychological distress was associated with bowel and systemic health deficits, more pain, higher perceived stress, an emotional representation of illness, less activities engagement, and greater number of gastroenterologist visits. Social impairment was associated with more pain, an emotional representation of illness, less activities engagement, symptom intolerance, greater number of gastroenterologist visits, and more missed work. Scores on the general HRQOL questionnaire (SF12v2), both physical and mental components, were correlated with bowel and systemic health, and less pain. However, only the scores on the mental component were related to less perceived stress, more disease acceptance, and fewer visits to the gastroenterologist; while the physical component was inversely related to missed work.

Our observed scores on the IBDQ were comparable to previous research,14,25 and our participants had scores comparable to the general population15 on the physical components summary of the SF-12v2. However, we found significant differences between our sample and the general population on the mental component summary of the SF-12v2, with our sample reporting lower emotional functioning.15

We were particularly enthusiastic about the potential relevance and utility of the DDAQ20 and the PDS24 in this population. These 2 measures show promise in assessing important aspects of disease impact/burden and a patient’s willingness to tolerate symptoms and engage in meaningful life activities despite chronic disease. Both measures demonstrated adequate internal consistency (i.e., scale reliability) within this IBD sample. The PDS shows promise in depicting perceived disability across 10 daily life domains in IBD. With only 10 items, it is easy to administer, score, and interpret. As expected, higher perceived disability scores were correlated with more bowel and systemic symptoms, abdominal pain, more perceived stress, psychological distress, greater number of gastroenterologist visits, and reduced activities engagement.

Disease acceptance and its impact on IBD quality of life and functioning has not previously been examined. For the purposes of this study, we adapted the widely used CPAQ developed by Geisser22 to digestive diseases. The CPAQ was designed to assess a patient’s willingness to tolerate symptoms of pain while maintaining active engagement in meaningful life activities despite the pain. McCracken and Eccleston23 furthered this work and sought to investigate the role of coping compared to acceptance of pain as predictors of pain perception, disability, depression, pain-related anxiety, “up-time,” and work status. They found that acceptance was significantly correlated with less pain, disability, depression, anxiety, more up-time, and better work status. Moreover, they found that “passive” coping strategies (i.e., distraction and praying/hoping) were consistently associated with greater pain, disability, depression, anxiety, less up-time, and work status. After controlling for coping contribution, acceptance significantly predicted less pain, disability, and distress.23 They concluded that higher acceptance of pain predicts more positive adjustment.

Our results show that scores on the DDAQ were significantly correlated with myriad adjustment variables in addition to the total score on the IBDQ. Symptom tolerance was significantly correlated with greater social functioning and emotional functioning, less emotional representation and negative consequence of illness, fewer gastroenterologist visits, and less missed work. While activities engagement was significantly related to bowel and systemic health, greater social and emotional functioning, less disability, longer length of time since diagnosis, less pain, less perceived stress, and less emotional representation and negative consequence of illness.

Moreover, our findings add to the coping literature in IBD. Jones et al6 found that patients with IBD, compared to controls, had higher psychological distress, poorer quality of life, less interpersonal support, and greater reliance on passive coping strategies. In their study, The Ways of Coping Questionnaire26,27 was used to assess thoughts and behaviors people use to cope with various situations. They found that patients with IBD engaged less in positive reframing and planful problem-solving than controls, but used more escape avoidance strategies, confrontative coping, and accepting responsibility. In contrast, we found the highest rated coping strategies were acceptance, seeking emotional support, active coping, and cognitive reframing, and that less effective coping strategies (such as substance use, venting, self-distraction, and self-blame) were associated with higher perceived disability, psychological distress, deficits in social functioning, and lower rated physical and mental health.

In comparison to multiple sclerosis (MS), adjustment has been investigated extensively and described in 2 ways: as a single dimension that includes variables such as psychological distress28 or self-concept29; or as a composite of constructs that includes variables such as psychological functioning and life satisfaction30: depression, global distress, social adjustment and health status,31,32 and positive thinking.33 Moreover, there is evidence that MS disease characteristics28,29,32,34 and disability,32 cognitive characteristics such as challenge appraisals,30–32 illness representations,28 acceptance,29 coping styles,29–32,34 social support,30,32,34 and stress31,32 are implicated in the adjustment process. The results of these studies underscore the complex nature of the adjustment process as well as the complexity in defining sensitive and specific measures to understand the process of adjustment to illness.

This study builds upon earlier IBD literature that has examined singular aspects of the process of psychological adjustment to IBD by refining the concept of adjustment to IBD following the Stanton et al11 model. This refinement includes development of a multidimensional model consisting of constructs typically targeted in other chronic diseases, including perceived disability and disease acceptance. Along these lines, the study conducted by Dorrian et al35 put forth a multifaceted model of adjustment whereby they sought to examine the extent to which adjustment to IBD is influenced by illness perceptions and coping. They conceptualized and measured adjustment in 3 parts: psychological distress, functional independence, and HRQOL. They found that disease and demographic variables explained a significant proportion of the variance in psychological distress (23%), functional independence (49%), and HRQOL (23%) and that illness perceptions explained a significant additional proportion of the variance in these same variables (32%, 21%, 23%, respectively). Interestingly, they found that coping behavior did not explain a significant proportion of the variance in these same variables. They concluded that disease and demographic variables as well as personal beliefs about their IBD play a significant role in adjustment to IBD. Our study also complements that of the Adler et al36 study of adjustment to college among young adults with IBD. Given their findings, they suggest that the presence of IBD was not only intrusive but also disruptive to the educational process and socialization among college students. We propose that the presence of IBD, with its relapsing and remitting course, is intrusive and potentially disruptive to life functioning including educational, occupational, emotional, and social functioning. In the absence of general and disease-specific adaptive strategies to deal with these potential disruptions, quality of life for individuals with IBD may suffer.

Our study was limited by a convenience sample of persons actively involved in their gastrointestinal health-care in a tertiary care clinic at a large academic medical center, those highly educated and predominantly white, and individuals with IBD for a long period of time. Thus, our sample is limited in the number of newly diagnoses individuals as well as those less educated and non-white, which limits the generalizability of our findings to more diverse patient groups. Also, this study was exploratory in nature, and served to assess construct and variable interrelationships. For a few variables, we observed very high correlations (i.e., greater than or equal to 0.80) that may suggest an autocorrelation effect, that is, variables may be highly correlated because they are essentially assessing the same latent construct. For instance, the BSI, the emotional subscale of the IBDQ, and the mental component of the SF12v2 are measuring a similar latent trait, that is, emotional well-being. Finally, we used relatively novel measures in this study and 2 in particular that have not been used in IBD previously. Based on these preliminary data, we report on the reliability of these 2 new measures. We recommend that future studies include a larger proportion of those individuals newly diagnosed (within 2 years preferably), more non-white participants (e.g., African-American and Hispanic GI patients), and, when possible, those individuals with less than college level education.

The strengths of this study include the robust results given the relatively small sample size. Consequently, the magnitude of the correlations suggests potential utility and statistical robustness of these variables in predicting patients reported outcomes, including quality of life. We observed significant differences across those individuals reporting flare versus remission, indicating that these constructs are discriminating across disease state. Also, this study highlights a novel approach to understanding patient outcomes in IBD using a multidimensional model of adjustment that may help to guide alternative treatment options (i.e., psychological and behavioral interventions) designed to enhance adaptive strategies and potentially increasing the quality of life for those with IBD. In conjunction with more recent literature on IBD, this study helps to support a framework for understanding psychological and other clinical mechanisms that may be contributing to primary outcomes for individuals with IBD, i.e., mechanisms consistent with a traditional biopsychosocial perspective.

CONCLUSIONS

There is an opportunity to build a framework for studying adjustment in IBD and investigate complementary, yet untapped, pathways of disease management. Future studies should address the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral contributors of adjustment to the nature and course of IBD, emphasizing the impact of healthy adjustment on clinical outcomes. Understanding adjustment from a multi-faceted perspective is critical to the advancement of the biopsychosocial approach in managing IBD. A better understanding of adjustment to IBD will enhance long-term treatment goals that facilitate managing disease-specific adaptive tasks, lessening the impact of disease on the individual both physically and psychologically, and enhancing quality of life for individuals with IBD.

Acknowledgments

No direct support was received for this study. Dr. Kiebles is supported by R21 AT003204. Dr. Keefer is supported by R21 AT003204 and U01 DK077738.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (R21 AT003204), National Institutes of Health (R21 AT003204 and U01 DK077738)

Footnotes

All study procedures were conducted at Northwestern Medical Faculty Foundation, Chicago, Illinois.

Author contributions: Jennifer L. Kiebles, PhD, contributed to the hypothesis, study design, assessment protocol development and execution, data and statistical analyses, article preparation and editing. Bethany Doerfler, MS, RD, contributed to the hypothesis, study design, and article editing. Laurie Keefer, PhD, contributed to the hypothesis, study design, assessment protocol development, and article editing.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Adult and Community Health. [Accessed February 27, 2009.]; http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dach/ibd.htm.

- 2.Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, et al. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsson K, Loof L, Ronnblom A, et al. Quality of life for patients with exacerbation in inflammatory bowel disease and how they cope with disease activity. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Iejk I, Vlachonikolis IG, Munkholm P, et al. The role of quality of care in health-related quality of life in patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:392–398. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordin K, Pahlman L, Larsson K, et al. Health-related quality of life and psychological distress in a population-based sample of Swedish patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;2002:450–457. doi: 10.1080/003655202317316097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones MP, Wessinger S, Crowell MD. Coping strategies and interpersonal support in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guthrie E, Jackson J, Shaffer J, et al. Psychological disorder and severity of inflammatory bowel disease predict health-related quality of life in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1994–1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen RD. The quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1603–1609. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guassora AD, Kruuse C, Thomsen O, et al. Quality of life study in a regional group of patients with Crohn’s disease: a structured interview study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1068–1074. doi: 10.1080/003655200451199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrak F, Hardt J, Clement T, et al. Impaired health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: psychosocial impact and coping styles in a national German sample. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:375–382. doi: 10.1080/003655201300051171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanton AL, Revenson TA, Hennen H. Health psychology: psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:565–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;96:804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irvine EJ. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: biases and other factors affecting scores. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1995;208:136–140. doi: 10.3109/00365529509107776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irvine EJ. Development and subsequent refinement of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality-of-life instrument for adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:S23–27. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al. How to score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (With a Supplement Documenting Version 1) Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, et al. The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychol Health. 2002;17:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, et al. Development of the perceived stress questionnaire: a new tool for psychosomatic research. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:19–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zinke JL, Keefer L. Adaptation of the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire to gastrointestinal disease: the development of the Digestive Diseases Acceptance Questionnaire. 2008 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carver CS. Want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geisser DS. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Reno, NV: University of Nevada; 1992. A comparison of acceptance-focused and control-focused psychological treatments in a chronic pain treatment center. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCracken LM, Eccleston C. Coping or acceptance: what to do about chronic pain? Pain. 2003;105:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckman N, Turer E, Scherdell T, et al. Long-term outcomes in chronic pain patients: The relationship between perceived disability, cognitive and affective factors, and adjustment [Abstract] J Pain. 2008;9(suppl 2):59. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, et al. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1224–1232. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48:150–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, et al. The dynamics of a stressful encounter, cognitive appraisal, coping and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiaffino KM, Shawaryn MA, Blum D. Examining the impact of illness representations on psychological adjustment to chronic illnesses. Health Psychol. 1998;17:262–268. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooks NA, Matson RR. Social-psychological adjustment to multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:2129–2135. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chalk HM. Mind over matter: cognitive-behavioral determinants of emotional distress in multiple sclerosis patients. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:556–666. doi: 10.1080/13548500701244965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pakenham KI, Stewart CA. The role of coping in adjustment to multiple sclerosis-related adaptive demands. Psychol Health Med. 1997;2:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pakenham KI. Adjustment to multiple sclerosis: application of a stress and coping model. Health Psychol. 1999;18:383–392. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pakenham KI. Making sense of illness or disability: the nature of sense-making in multiple sclerosis (MS) J Health Psychol. 2008;13:93–105. doi: 10.1177/1359105307084315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCabe MP, McKern S, McDonald E. Coping and psychological adjustment among people with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:355–361. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorrian A, Dempster M, Adair P. Adjustment to inflammatory bowel disease: the relative influence of illness perceptions and coping. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:47–55. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adler J, Raju S, Beveridge AS, et al. College adjustment in University of Michigan students with Crohn’s and colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1281–1286. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]