Abstract

Background

A small proportion of patients with ALS survive more than five years. The frequency of five year or longer survival with ALS in a United States population is unknown but may provide a baseline for studies that employ survival as a primary endpoint of analysis.

Methods

All persons diagnosed with ALS in Olmsted County between 1925 and 2004 were studied for demographic and clinical features. Longer term survivors were defined as patients who lived five years or longer, tracheostomy-free, following symptomatic onset.

Results

94 patients (mean survival from symptomatic onset 2.95 years (95% CI 2.54–3.35), mean survival from diagnosis 1.89 years, (95% CI 1.54–2.24)) were diagnosed with ALS. Five-year or longer survivors accounted for 14% of the population of patients (95% CI 7.9%–22.8%). The frequency of five year or longer survivors did not change over time. Mean survival of these individuals was 7.04 years (95% CI 6.14–7.94 years; range 5.11–9.35 years). They had a significantly longer mean time to diagnosis (1.77 years, 95% CI 0.95–2.58 years) as compared to less than five year survivors (0.94 years, 95% CI 0.75–1.13 years) (p=0.02) but could not be reliably identified at the time of diagnosis by age, sex, clinical presentation, or El Escorial category.

Conclusion

Patients surviving more than five years following the symptomatic onset of ALS account for 14% of the total ALS population. This frequency has not changed over time. Patients with five year or longer survival are clinically similar to the total population ALS population in terms of age, gender, presentation, and site of onset but have a longer time from symptomatic onset to diagnosis.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, natural history, prognosis, survival

Background

It has long been recognized that some patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have a protracted course of illness. In his initial description of ALS, Jean-Martin Charcot (1874) wrote (tr): “Death follows in 2 or 3 years, on average, from the onset of bulbar symptoms. This is the rule but there are a few anomalies.”1 Nearly 70 years later, Swank and Putnam2 (1943) characterized presentations of ALS in which an unexpectedly long survival could occur, concluding that at least five percent of patients with ALS have a “prolonged” survival. Mulder3 (1976) concurred, and found that “many” patients with ALS (20%) live more than five years from symptom onset, and may even “regress,” but otherwise have a disease clinically indistinct from those who do not. In 2003, a collected case series of 30 patients with the diagnosis of ALS who survived 10 years or more was presented.4 At times, the term “benign ALS” has been used to describe these select patients.5

Establishing the frequency and characteristics of longer term survivors of ALS in a United States population may be useful for clinical studies which employ survival as a primary endpoint of analysis, allowing assessment of how many patients in a given population would live five years or more at baseline. In Olmsted County, neurologists have been recording cases of ALS since 1925, data which have been used to estimate prevalence and incidence of ALS in the general population. Here, we identify individuals with ALS who have survived unexpectedly longer than the average. Their clinical characteristics, symptomatic presentations, and overall survival times are analyzed. We also determine whether the rate of five year or more survival in a longitudinally-extensive population study has changed over time.

Methods

Patients with ALS, diagnosed between 1 Jan 1925 and 30 Jun 2004, were identified through the Rochester Epidemiology Project. All persons living in Olmsted County (population 133 154 in 2004) for at least one year before the diagnosis of ALS were included. All were followed until the time of death and diagnosed by a neurologist. For any given three year-interval, more than 98 percent of the residents of Olmsted County appear in the Rochester Epidemiology Project database. The date of censoring for this analysis was 30 June 2009.

Longer term survivors with ALS (LTS) were defined here as people living more than five years of tracheostomy-free life following symptomatic onset of (a) progressive weakness (spastic or flaccid) and/or (b) bulbar symptoms. Bulbar onset was defined as the first signs or symptoms of dysarthria and/or dysphagia, not related to other causes. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis encompassed the presentations of upper motor neuron-onset illness (primary lateral sclerosis (PLS)), lower motor neuron-onset illness (progressive muscular atrophy), and progressive bulbar palsy. In this database, patients with PLS presentations were included only if they eventually developed lower motor neuron signs. El Escorial diagnostic criteria (1994)6 were used, retrospectively where necessary, to separate patients into suspected, possible, probable, or definite ALS at the time of diagnosis.

Statistical comparisons of means were conducted using two-sample t-tests, while two-sample continuity-corrected Z-tests were used to compare proportions; all tests of hypothesis were performed under two-sided alternatives.7,8 Confidence intervals for means were obtained by inverting one-sample two-sided t-tests, while confidence intervals for all proportions were constructed using the score interval along with Yates’ continuity correction.7,8 Estimates of the survival curve were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier estimator9 (here equivalent to the empirical cumulative distribution function in view of the absence of censored observations). When studying the relationship between proportions of interest and multiple predictors, logistic linear regression models were employed.7 The programming language R© version 2.8.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)10 was used to perform all statistical computations.

The Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

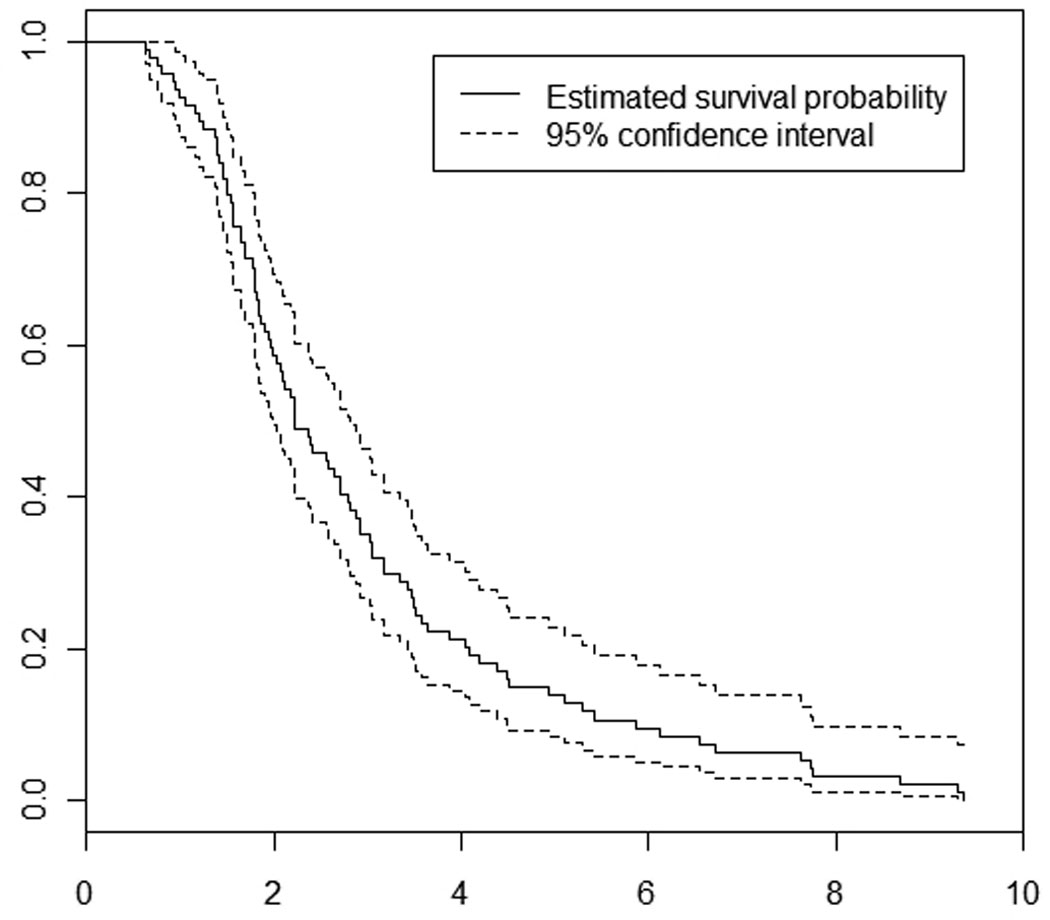

A total of 94 patients (51 men; mean survival from symptomatic onset 2.95 years (95% CI 2.54–3.35 years), mean survival from diagnosis 1.89 years, 95% CI 1.54–2.24 years) were identified of whom 13 (13.8%, 95% CI 7.9%–22.8%; 8 men) survived five years or more following disease onset (Figure 1). The mean survival among LTS was 7.04 years (95% CI 6.14–7.94 years), and ranged from 5.11 to 9.35 years. The mean time from symptomatic onset to diagnosis for the entire population was 1.06 years (95% CI 0.86–1.26 years). LTS had a significantly longer mean time from symptomatic onset to diagnosis of 1.77 years (95% CI 0.95 to 2.58 years) as compared to non-LTS of 0.94 years (95% CI 0.75–1.13 years) (p=0.02). There were 6 patients who survived five years or longer from the time of diagnosis (6/94, 6.38%; 95% CI 2.38–13.38). All long term survivors identified in the study period have now died.

Figure 1.

Survival function for all individuals with ALS in Olmsted County (1925–2004)

Bulbar symptoms were present in 30 percent of patients at onset (28 out of 92 patients with information about bulbar symptoms at onset; 95% CI 21.27–40.90%). Bulbar symptoms were less likely to be the initial presentation of LTS (2/13) as compared to non-LTS (26/79 = 33%), though this difference was deemed not to be statistically significant (p=0.34). Age at diagnosis, calendar year of disease onset, and sex did not influence the frequency of long term survival in ALS, as verified by logistic linear regression models. Six patients (6%) had a family history of ALS in a primary relative but no LTS had a known positive family history of ALS.

Presentation at the time of initial evaluation, among LTS, was lower motor neuron in 5, upper motor neuron in 1, and combined lower and upper motor neuron in 7. In 3 patients, the "flail limb" syndrome was the phenotypic presentation of ALS while in 2, bulbar palsy was the initial presentation (Table 1). El Escorial category at the time of first evaluation was available in the 81 patients who had an EMG. Patients were categorized as definite (0/13 LTS, 9/68 non-LTS), probable (7/13 LTS, 23/68 non-LTS), possible (0/13 LTS, 8/68 non-LTS), and suspected (1/13 LTS, 13/68 non-LTS). Some patients did not meet criteria for even the suspected category at first evaluation (5/13 LTS, 15/68 non-LTS). In some patients, precise information was unavailable to accurately ascribe an El Escorial category, retrospectively, for the time of first evaluation (0/13 LTS, 9/68 non-LTS).

Table One.

Clinical features of long term survivors of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Olmsted County (1925–2004)

| Age at Onset /Sex |

First Symptoms | Time from Symptom Onset to Diagnosis of ALS (months) |

Time from Symptom Onset to first Bulbar Symptoms (months) |

UMN or LMN symptoms at presentation |

El Escorial Category at Time of Diagnosis |

Clinical Presentation |

Survival from Symptom Onset (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51F | Speech Difficulty | 16 | 0 | UMN | Did not meet criteria |

Bulbar Palsy |

82 |

| 74F | Bilateral UE weakness, wasting |

22 | No bulbar symptoms |

LMN | Suspected | Flail Limb | 67 |

| 56M | Right UE weakness, pain |

9 | U/A | LMN | Probable | Flail Limb | 113 |

| 51M | Hand weakness | 38 | 53 | LMN | Probable | Typical Limb-Onset ALS |

75 |

| 39M | Bilateral Hand Weakness |

9 | 19 | LMN | Possible | Typical Limb-Onset ALS |

70 |

| 69F | Hand weakness and atrophy |

1 | 40 | LMN | Probable | Typical Limb-Onset ALS |

79 |

| 49M | Leg stiffness | 25 | 52 | LMN+UMN | Probable | Typical Limb-Onset ALS |

94 |

| 58M | UE weakness | 10 | 57 | LMN+UMN | Probable | Typical Limb-Onset ALS |

114 |

| 75M | Bilateral UE fasciculations |

52 | 100 | LMN | Did not meet criteria |

Progressive Muscular Atrophy |

106 |

| 58M | Dysarthria | 45 | 0 | LMN+UMN | Did not meet criteria |

Bulbar Palsy | 94 |

| 74F | UE weakness | 37 | 89 | LMN+UMN | Probable | Flail Limb | 93 |

| 64M | Foot drop | 7 | 29 | LMN+UMN | Did not meet criteria |

Typical Limb-Onset ALS |

65 |

| 49F | UE weakness, cramps, fasciculations |

8 | 10 | LMN+UMN | Did not meet criteria |

Typical Limb-Onset ALS |

62 |

Comparisons based on a dichotomization of year of diagnosis to pre- and post-1964 suggested that neither the proportion of LTS (p=0.45) nor mean survival (p=0.26) varied over time. Dichotomization at the observed median year of diagnosis (1983) yielded similar results. Conclusions were also similar using other categorizations of year of diagnosis as well as using year of diagnosis as a continuous variable and adjusting for other potential confounders in a logistic regression model. In 13 patients, ALS was diagnosed before the advent of electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies. There were no LTS in this group of early patients who did not undergo electrophysiologic evaluation.

An additional analysis was made in patients who presented with limb-only symptoms. Disease course was separated into (a) time from limb symptom onset to time of bulbar symptom onset and (b) time of bulbar symptom onset to death. The proportions of LTS and non-LTS who developed bulbar symptoms following limb onset were not significantly different. LTS had longer mean disease duration from both limb onset to bulbar onset and from bulbar onset to death as compared to non-LTS. Mean duration between limb onset and bulbar onset was 4.64 years in LTS (95% CI 2.93–6.35) compared to 1.33 years in non-LTS (95% CI 0.97–1.69) (p=0.04). Mean duration between bulbar onset and death was 2.28 years in LTS (95% CI 0.95–3.62) compared to 0.90 years in non-LTS (95% CI 0.70–1.10) (p=0.002).

No patient surviving five years or longer took riluzole, although four LTS were diagnosed after the drug became available. Overall, less than 10% of eligible patients took riluzole in Olmsted County. Similarly, no LTS had a tracheostomy placed.

Discussion

Patients surviving more than five years following the symptomatic onset of ALS account for 14% of the total ALS population. The frequency of five year or longer survivors has not changed over time. Patients with five year or longer survival are clinically similar to the total population of patients with ALS in terms of age, gender, and site of onset. There is a longer time to diagnosis in LTS and this diagnostic latency is particularly important in identifying potential LTS of ALS. LTS had increased survival, both before and after bulbar symptom onset, compared to non-LTS, in this same population.

The absolute duration of long term survival is also notable. Over the observation period of nearly a century, we identified 13 patients surviving five years or more in Olmsted County. All died within 10 years of onset. This differs from other reports in which a significant proportion of patients with ALS have been found to live well beyond 10 years.4,11–13 In a recent review of five other population-based studies of ALS patients, it was found that 5 to 10 percent of ALS patients survived longer than 10 years in all other databases.14 Notably, this population-based study only includes patients with PLS if they develop lower motor neuron features prior to death. Because patients with PLS are recognized to have prolonged survival compared to patients with combined UMN and LMN features, and other studies include patients with PLS presentations with and without evolution to combined features, this may at least partially explain why no patients in this database have lived more than 10 years. Given the few patients who choose to try riluzole (which was licensed for use in 1996), and none were our LTS, we are unable to ascertain whether this drug has had any impact on the frequency of longer survival.

Reported population-based 5-year survival rates, from symptomatic onset of ALS, vary widely from 7% (Denmark)15, 15% (France),16 and 28% (Scotland)17. In Turin, Italy, 5-year survival from diagnosis was reported to be 28%11 while in western Washington state, U.S.A., it was just 7%.18 In a non-population-based U.S. study, 5-year survivorship was estimated at 39.4%19, likely representing length and referral biases. Although our sample size is not large, the current analysis is population-based with no patients lost to follow up over the entire observation period.

Previous investigators have isolated variables associated with prolonged survival, including upper motor neuron features at onset,4,13 non-bulbar presentation15–18, male sex16,18 and younger age.4, 13, 16,18 LTS in Olmsted County were not significantly younger than non-LTS in this cohort, and only one LTS received the initial diagnosis of PLS. A “flail limb syndrome” has been described as prognostically favorable.19 Three LTS had a presentation consistent with a single limb “flail limb” phenotype. Two patients (15%) living five years or more from symptomatic onset presented with bulbar symptoms. This finding confirms previous studies that identified few patients with bulbar onset among LTS.4,11,13

Overall, 14 percent of patients with the diagnosis of ALS live five years or more following symptomatic onset in Olmsted County. These patients have a longer time to diagnosis but otherwise cannot be reliably identified at the time of initial presentation, by clinical features or through El Escorial criteria. In spite of availability of advanced care for ALS patients in recent decades, long term survival does not seem to have changed in frequency over the study observation period of 85 years.

Footnotes

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://jnnp.bmjjournals.com/ifora/licence.pdf).

Conflicts of Interest: None Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Translation in: Rowland LP. How amyotrophic lateral sclerosis got its name. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:512–515. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.512.

- 2.Swank RL, Putnam TJ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and related conditions. Arch Neurol Psych. 1943;49:151–177. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulder DW, Howard FM., Jr Patient resistance and prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1976;51:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner MR, Parton MJ, Shaw CE, Leigh PN, Al-Chalabi A. Prolonged survival in motor neuron disease: a descriptive study of the King’s database 1990–2002. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:995–997. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norris F, Shepher R, Denys E, U K, Mukai E, Elias L, et al. Onset, natural history and outcome in idiopathic adult motor neuron disease. J Neurol Sci. 1993;118:48–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90245-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks BR, et al. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1994;124:96–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. United States of America: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosner BA. Fundamentals of biostatistics. United States of America: Duxbury; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 10.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mortara P, Chiò A, Rosso MG, Leone M, Schiffer D. Motor neuron disease in the province of Turin, Italy, 1966–1980. J Neurol Sci. 1984;66:165–173. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(84)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen AD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical features and prognosis. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:638–642. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1978.00500340014003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoccolella S, Beghi E, Palagano G, Fraddosio A, Guerra V, Samarelli V, Lepore V, et al. Predictors of long survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. J Neurol Sci. 2008:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chío A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O, Swingler R, Mitchell D, et al. Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10:310–323. doi: 10.3109/17482960802566824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christensen PB, Højer-Pederson E, Jensen NB. Survival of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 2 Danish counties. Neurology. 1990;40:600–604. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.4.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preux PM, Couratier P, Boutros-Toni F, Salle JY, Tabaraud F, Bernet-Bernady P, et al. Survival prediction in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Age and clinical form at onset are independent risk factors. Neuroepidemiology. 1996;15:153–160. doi: 10.1159/000109902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chancellor AM, Slattery JM, Fraser H, Swingler RJ, Holloway SM, Warlow CP. The prognosis of adult-onset motor neuron disease: a prospective study based on the Scottish Motor Neuron Disease Register. J Neurol. 1993;240:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00839964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.del Aguila MA, Longstreth WT, Jr, McGuire V, Koepsell TD, van Belle G. Prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurology. 2003;60:813–819. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000049472.47709.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neurology LC, Mathers S, Talman P, Galtrey C, Parkinson MH, et al. Natural history and clinical features of the flail arm and flail leg ALS variants. Neurology. 2009:1087–1094. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345041.83406.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]