Abstract

Background

Moderate alcohol intake is associated with lower risk of coronary heart disease, but the association with SCD is less clear. In men, heavy alcohol consumption may increase risk of SCD, while light-to-moderate alcohol intake may lower risk. There are no parallel data among women.

Objective

We assessed the association between alcohol intake and risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) among women, and investigated how this risk compared to other forms of CHD.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study among 85,067 women from the Nurses’ Health Study free of chronic disease at baseline. Alcohol intake was assessed every 4 years through questionnaires. Primary end points included SCD, fatal CHD, and nonfatal myocardial infarction.

Results

We found a U-shaped association between alcohol intake and risk of SCD, with the lowest risk among women who drank 5.0–14.9 g/day of alcohol (p for quadratic trend= 0.02). Compared to abstainers, the multivariate relative risk (95% confidence interval) for SCD was 0.79 (0.55-1.14) for former drinkers, 0.77 (0.57, 1.06) for 0.1– 4.9 g/day, 0.64 (0.43– 0.95) for 5.0 –14.9 g/day, 0.68 (0.38–1.23) for 15.0 –29.9 g/day, and 1.15 (0.70-1.87) for ≥30.0 g/day. In contrast, the relationship of alcohol intake and nonfatal and fatal CHD was more linear (P for linear trend<0.001).

Conclusions

In this cohort of women, the relationship between light-to-moderate alcohol intake and SCD is U-shaped with a nadir at 5.0–14.9 g/day. Low levels of alcohol intake do not raise risk of SCD and may lower risk in women.

Keywords: Sudden cardiac death, Acute coronary syndromes, Acute myocardial infarction, Epidemiology, Alcohol, Nutrition, Risk Factors

Introduction

Numerous studies support a protective association of moderate alcohol intake on risk of coronary heart disease (CHD)(1). Moderate alcohol may lower risk of other cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including stroke(2) and congestive heart failure(3), but the association with arrhythmic disorders is less clear. Previous research has focused on the pro-arrhythmic effects of heavy alcohol consumption and binge drinking, including increased risk of supraventricular arrhythmias (“holiday heart syndrome”)(4) and sudden cardiac death (SCD)(5,6).

On the other hand, moderate alcohol intake was not associated with higher risk of SCD(6-8), and in some populations, was associated significantly with lower risk(9-12), compared to abstainers. In the latter studies, conducted among primarily male populations, alcohol had a U-shaped association with SCD risk; however whether the same relation applies to women is uncertain. In general, the health effects of alcohol intake among women, both beneficial and adverse, are apparent at lower levels of intake compared to men. We previously assessed the relation of moderate alcohol consumption and CHD in the Nurses’ Health Study(13), which has followed 121,700 apparently healthy women since 1976, and has repeatedly assessed alcohol intake. In this analysis, we prospectively explore the role of alcohol intake on risk of SCD among women, and investigated how this risk compares to other forms of CHD.

Methods

Study population

The Nurses’ Health Study is a prospective cohort of 121,700 registered female nurses, aged 30 to 55 y at baseline in 1976. Participants completed a mailed questionnaire inquiring about medical history, cardiovascular and lifestyle risk factors, and this information is updated biennially. We collected dietary information using a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) administered in 1980 and approximately every 4 years thereafter. We excluded women who were missing information on alcohol intake or reported implausible dietary data (10 or more food items blank, or energy intake <600 or >3500 kcal per day) on the 1980 FFQ. We also excluded women who reported a diagnosis of CVD or cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer) prior to 1980. The Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital approved the study protocol.

Alcohol intake

In 1980, the FFQ included separate questions about beer, wine and liquor. Separate questions on red and white wine were introduced on the 1984 questionnaire, and a question on low-calorie beer was introduced in 1994. Each participant was asked how often, on average, she consumed each beverage type over the past year, using standardized portions of each beverage [12-oz of beer, 4-oz of wine, and a 1.5-oz of liquor]. We calculated average alcohol intake by multiplying the frequency of each beverage by its ethanol content (beer: 12.8 g; light beer: 11.3 g; wine: 11.0 g; liquor: 14.0 g) and summing across all beverages. One drink is approximately 15 grams. Alcohol intake, as estimated from the FFQ, is highly reproducible over a 1-2 year period (r=0.86-0.87) and is strongly correlated with alcohol intake estimated from dietary records (r=0.90) and HDL cholesterol (r = 0.40)(14).

To avoid potential bias from including “sick quitters” in the referent category, we separated nondrinkers into lifetime abstainers and former drinkers. We defined a former drinker in 2 ways. At baseline, women who reported consuming no alcohol in 1980 and reported a decrease in alcohol intake within the previous 10 years were classified as former drinkers. During follow-up, we classified women as former drinkers if they reported no alcohol intake on the current questionnaire, but non-zero intake on the previous questionnaire. We categorized daily alcohol intake into six categories: abstainer, former drinker, 0.1-4.9 (~<½ drink), 5.0-14.9 (~1/2-1 drink), 15.0-29.9 (~1-2 drinks), ≥30.0 g/day (~≥2 drinks).

Endpoint Ascertainment

The study end points were SCD, other fatal CHD, and nonfatal myocardial infarction(MI). Deaths were either reported by next of kin or postal authorities or identified through a search of the National Death Index. Death certificates were obtained to confirm deaths, and we sought permission to obtain further information from medical records or family members. The next of kin were interviewed about the circumstances surrounding the death if not adequately documented in the medical record.

Specific details for the classification of SCD have been described in detail elsewhere(15). Briefly, cardiac deaths were considered sudden if the death or cardiac arrest occurred within 1 hour of symptom onset as documented by medical records or through reports from next of kin. To increase the specificity for an “arrhythmic death”, we excluded women with evidence of circulatory collapse (hypotension, exacerbation of congestive heart failure or neurologic dysfunction) before disappearance of the pulse, based on the definition by Hinkle and Thaler(16). We considered unwitnessed deaths that could have occurred within 1 hour of symptom onset, and that had autopsy findings consistent with SCD, as probable cases (n=34, 12%) and included these in our analysis.

Fatal CHD was defined as ICD-9 codes 410-412 if confirmed by hospital records or autopsy, or if CHD was listed as the cause of death on the death certificate, along with evidence of prior CHD. Cases in which CHD was the underlying cause on the death certificate, but for which no medical records concerning the death were available, were designated as presumed CHD and included in the analysis. Additionally, all CHD deaths that did not fulfill the criteria for SCD were designated other CHD deaths for these analyses.

When a participant reported a nonfatal MI on a biennial questionnaire, we requested permission to obtain their medical records, which were reviewed by study investigators blinded to the participants’ risk factor status. MI was defined according to World Health Organization criteria and, cardiac-specific troponin levels, when available(17). MIs that required hospital admission and were verified by letter or telephone interview, but for which medical records or pathology reports were unavailable, were defined as probable cases and included in the analysis. Results were similar if probable cases were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

We performed separate analyses for SCD, non-sudden fatal CHD and nonfatal MI. For the analysis of fatal events, women contributed person-time from the return of the baseline questionnaire in 1980 until the date of death or June 1, 2006, which ever came first. We did not censor women at the time of development of nonfatal MI. For the non-fatal endpoint, women contributed person-time from the return of the baseline questionnaire in 1980 until the date of nonfatal MI, death or June 1, 2006.

For descriptive purposes, we computed age-adjusted means and proportions of risk factors for the 6 categories of alcohol intake at the midpoint of follow-up (1994). We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the relative risk, adjusted for age, calories, smoking, BMI, parental history of MI, menopausal status, use of postmenopausal hormones, aspirin use, multivitamin and vitamin E supplements, physical activity and intake of marine omega-3 fat, alpha-linolenic fat, trans fat, and ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fat. In separate models, we furthered adjusted for diagnosis of stroke, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and CHD (for fatal analyses only), which are potential intermediates through which alcohol influences risk of SCD and CHD.

We hypothesized that most recent intake would have the greatest influence on CHD risk; therefore, we constructed time-varying Cox models where alcohol intake was updated at the time of each questionnaire assessment and the most recent alcohol measurement was used to estimate risk in the following time period (approximately 4 year risk). In these models, alcohol in 1980 predicts risk of SCD from 1980 to 1984, alcohol in 1984 predicts risk from 1984 to 1986, and alcohol in 1986 predicts risk from 1986 to 1990, etc. In multivariable models, other covariates were updated at various time points, and if data were missing at a given time point, the last observation was carried forward. To test for a linear trend in the categorical analysis, we excluded former drinkers and treated the median value of each alcohol category as a linear variable. Based on our prior hypothesis, we tested for a curvilinear association between alcohol and SCD by creating a quadratic term that squared this linear variable centered at the median of the lowest risk category and including it in a separate model with the linear term. The continuous measure of alcohol consumption was also used to fit a restricted cubic spline model, using 3 knots(18,19). To make the graph more stable and meaningful, we excluded women with alcohol intake greater than 50 g/day (0.7% of person-years) and former drinkers (13%).

The risk of SCD associated with individual beverage types (beer, wine, and liquor) was assessed using updated measures of intake, after separating the abstainers from former drinkers. In the multivariate model, we included the intake of all beverage types simultaneously. A single category of ≥15.0 g/day of each individual beverage was created due to the small number of participants in the higher intake categories.

In pre-specified secondary analyses, we explored a potential interaction between alcohol intake and incident CHD during follow-up. To test formally for interaction, we modeled the cross-product term between alcohol and CHD, and used a likelihood ratio test to compare models with and without the interaction term. Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Population characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants categorized at the midpoint of follow-up (1994), according to usual alcohol consumption. Over the course of the study, 26% of the women were abstainers, 50% of the women consumed up to 15 g/day (1 drink), 4% reported consuming 30.0-49.9 g/day (approximately 2-4 drinks), and <1% reported consuming ≥50.0 g/day (≥4 drinks). As compared with abstainers, women who consumed greater amounts of alcohol tended to be current smokers, but also have a lower prevalence of diabetes, a lower BMI, ex ercise more, have lower intake of trans fat, and higher intake of omega-3 fat.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics* across quintiles of alcohol intake among women in the Nurses’ Health Study in 1994

| Categories of alcohol intake (g/day)† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abstainers | Former drinkers |

0.1-4.9 | 5.0-14.9 | 15.0-29.9 | 30.0+ | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61 | 61 | 60 | 60 | 61 | 61 |

| Current smokers (%) | 10 | 13 | 12 | 15 | 17 | 29 |

| Reported diagnosis of | ||||||

| Hypertension (%) | 40 | 41 | 35 | 32 | 34 | 41 |

| Diabetes (%) | 10 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| High cholesterol (%) | 48 | 52 | 48 | 45 | 43 | 45 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 | 27.1 | 26.5 | 25.2 | 24.9 | 25.1 |

| Family history of MI before age 60 (%) | 12 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Post-menopausal (%) | 81 | 84 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 83 |

| Current use of HRT (%) | 31 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 33 |

| Aspirin use, ≥7 times / week (%) | 10 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 |

| Vitamin supplement use | ||||||

| Vitamin E (%) | 21 | 29 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 24 |

| Multivitamin (%) | 35 | 48 | 41 | 41 | 39 | 37 |

| Moderate to vigorous physical activity (hours/week ) | 2.9 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.4 |

| Alcohol (g/day) | 0 | 0 | 2.1 | 9.5 | 21.1 | 41.2 |

| Beer (g/day) | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 7.4 |

| Wine (g/day) | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 11.2 | 9.9 |

| Liquor (g/day) | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 23.4 |

| Omega-3 fat (mg/day). | 191 | 206 | 223 | 238 | 258 | 225 |

| Alpha-linolenic acid fat (g/day) | 0.9 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| Trans fat (% energy) | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

All characteristics are age-standardized with the exception of age

One drink is ~15 grams of alcohol

Alcohol intake and risk of sudden cardiac death

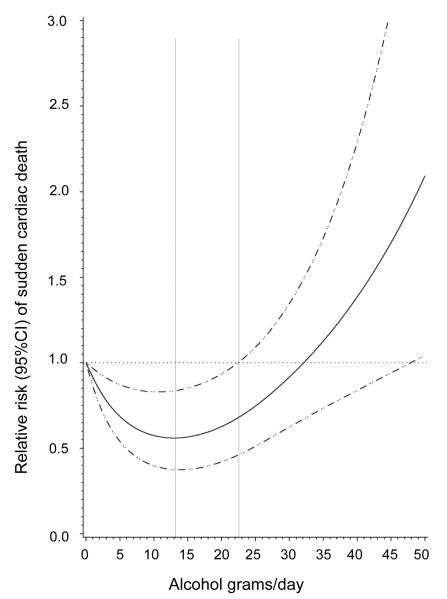

Over 26 years of follow-up, we documented 295 cases of SCD, 987 cases of non-sudden CHD deaths and 2195 cases of nonfatal MI. We found a U-shaped association between light-to-moderate alcohol consumption and risk of SCD in age and calorie-adjusted, as well as multivariate adjusted, models (Table 2). After adjustment for diet, lifestyle and other CVD risk factors, the lowest risk of SCD occurred among women who consumed 5.0 to 14.9 g of alcohol daily (approximately ½-1 drink per day). The risk among women in the highest category of alcohol intake (≥30 g or ~≥2 drinks/day) did not significantly differ from the risk observed among the abstainers. There was no evidence for a linear trend, but the test for nonlinear trend was significant and consistent with the observed U-shaped relation. The restricted cubic spline curve also confirmed the U-shaped association (P=0.003) between alcohol intake and SCD risk (Figure). In the spline model, the lowest risk of SCD occurred at approximately 13 g/day of alcohol, and alcohol intake of up to 22 g/day was associated with significantly lower risk compared to 0 g/day.

Table 2.

Relative risks (95% confidence intervals) of SCD according to categories of total alcohol intake

| Categories of alcohol intake (g/day)* | P-trend | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abstainers | Former drinkers | 0.1-4.9 | 5.0-14.9 | 15.0-29.9 | 30.0+ | linear | quadratic | |

| Median alcohol intake (g/day) | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 9.5 | 18.8 | 36.9 | ||

| cases | 108 | 46 | 70 | 36 | 13 | 22 | ||

| Person-years | 563903 | 282569 | 682411 | 432246 | 143572 | 97271 | ||

| IR (per 100,000 py) | 19 | 16 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 23 | ||

| Age, calorie adjusted | 1.0 (ref) | 0.63 (0.45-0.90) | 0.60 (0.44-0.81) | 0.47 (0.32-0.69) | 0.49 (0.27-0.87) | 1.19 (0.75-1.89) | 0.83 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate model 1† | 1.0 (ref) | 0.78 (0.54-1.12) | 0.67 (0.49-0.91) | 0.54 (0.36-0.80) | 0.58 (0.32-1.05) | 1.01 (0.62-1.64) | 0.86 | 0.002 |

| Multivariate model 2‡ | 1.0 (ref) | 0.79 (0.55-1.14) | 0.77 (0.57-1.06) | 0.64 (0.43-0.95) | 0.68 (0.38-1.23) | 1.15 (0.70-1.87) | 0.7 | 0.02 |

One drink is ~15 grams of alcohol

Multivariate model 1 adjusted for age (months), calories (continuous), smoking (5 categories), BMI (<25, 25-29.9, 30+ kg/m2), parental history of MI (no, < 60 years, ≥60 years), menopausal status (yes/no), use of postmenopausal hormones (current, past, never), aspirin use <1, 1-6 or ≥7 per week), multivitamin and vitamin E supplements (yes/no), physical activity (hours/week) and intake of marine omega-3 fat, alpha-linolenic fat, trans fat, and ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fat (all in quintiles)

Multivariate model 2 further adjusted for diagnosis of CHD, stroke, diabetes, high blood pressure or high cholesterol.

Figure.

Multivariate Relative Risk of SCD as a Function of Alcohol Intake Data were fitted by a restricted cubic spline Cox proportional hazards model. The 95% confidence intervals are indicated by the dashed lines. Models adjusted for age, calories, smoking, BMI, parental history of MI, menopausal status, use of postmenopausal hormones, aspirin use, multivitamin and vitamin E supplements, physical activity and intake of omega-3 fatty acid, alpha-linolenic fatty acid, trans-fatty acid, ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids, diagnosis of CHD, stroke, diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol. The spline was based on 247 cases after the exclusion of former drinkers and women with intake >50 g/day.

We found similar results when we restricted our endpoint to definite cases of SCD (p-quadratic trend 0.02), and when we considered nondrinkers (abstainers + former drinkers) as the referent category (p-quadratic trend=0.01). We found no evidence that the benefit of alcohol was restricted to one type of beverage (beer, wine or liquor). The relative risk comparing light-to-moderate drinkers (5-14.9 g/d) to abstainers was similar in magnitude for all beverage types (RR = 0.78 for beer, 0.84 for wine, 0.77 for liquor). However, due to sparse data in these analyses, relative risks were not statistically significant and our power to detect differences between these relative risks was limited. We also did not find any significant difference in the association between alcohol intake and SCD among women with a history of diagnosed CHD (p-interaction=0.87).

Alcohol intake and risk of non-sudden CHD

In contrast to the U-shaped association observed with SCD, the association between alcohol intake and nonfatal MI was more linear (p-linear trend<0.001) (Table 3). For non-fatal MI, stronger risk reductions were apparent at higher levels of intake. The lowest risk of nonfatal MI occurred among women who consumed ≥30 g/day of alcohol (RR: 0.56; 95%CI: 0.44-0.71). Alcohol intake was inversely associated with risk of fatal CHD, with significant reductions in risk observed at any level of alcohol intake in multivariable models. The risk of nonfatal MI or fatal CHD among former drinkers was not significantly different from the risk among abstainers.

Table 3.

Relative risks (95% confidence intervals) of nonfatal MI and non-sudden fatal CHD according to categories of total alcohol intake

| Categories of alcohol intake (g/day)* | P-trend | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abstainers | Former drinkers | 0.1-4.9 | 5.0-14.9 | 15.0-29.9 | 30.0+ | linear | quadratic | |

| Median alcohol intake (g/day) | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 9.5 | 18.8 | 36.9 | ||

| Nonfatal MI | ||||||||

| Cases | 645 | 395 | 625 | 350 | 94 | 86 | ||

| Multivariate model 1† | 1.0 (ref) | 0.95 (0.84-1.08) | 0.85 (0.76-0.95) | 0.69 (0.61-0.79) | 0.56 (0.45-0.69) | 0.56 (0.44-0.71) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate model 2‡ | 1.0 (ref) | 0.95 (0.84-1.08) | 0.94 (0.84-1.05) | 0.79 (0.69-0.91) | 0.63 (0.50-0.79) | 0.59 (0.46-0.75) | <0.001 | 0.09 |

| Non-sudden fatal CHD | ||||||||

| Cases | 428 | 187 | 207 | 94 | 28 | 45 | ||

| Multivariate model 1† | 1.0 (ref) | 1.00 (0.83-1.20) | 0.56 (0.47-0.66) | 0.38 (0.30-0.47) | 0.35 (0.23-0.51) | 0.54 (0.39-0.74) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate model 2‡,§ | 1.0 (ref) | 1.05 (0.87-1.27) | 0.71 (0.60-0.85) | 0.52 (0.41-0.66) | 0.49 (0.33-0.73) | 0.69 (0.50-0.96) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

One drink is approximately 15 grams of alcohol

Multivariate model 1 adjusted for age (months), calories (continuous), smoking (5 categories), BMI (<25, 25-29.9, 30+ kg/m2), parental history of MI (no, < 60 years, ≥60 years), menopausal status (yes/no), use of postmenopausal hormones (current, past, never), aspirin use <1, 1-6 or ≥7 per week), multivitamin and vitamin E supplements (yes/no), physical activity (hours/week) and intake of marine omega-3 fat, alpha-linolenic fat, trans fat, and ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fat (all in quintiles)

Multivariate model 2: further adjusted for diagnosis of stroke, diabetes, high blood pressure or high cholesterol.

Also adjusted for diagnosis of CHD

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of women, free of reported CVD at study entry, the relationship between light-to-moderate alcohol intake and SCD was U-shaped; women with alcohol intake of 5.0-14.9 g or approximately ½-1 drinks per day had a 36% lower risk of SCD compared to abstainers, and there was no evidence that the benefit of alcohol was restricted to one type of beverage. Higher intakes of alcohol (>30 g or 2 drinks/day) were not associated with increased risk of SCD; however, the number of SCD among women who consumed >30 g/day was limited. In contrast, the association between alcohol and non-sudden cardiac events was more linear with significantly lower relative risks at higher levels of alcohol intake. This inverse association between alcohol and non-sudden CHD risk was remarkably consistent with results observed in the prior report from this cohort, with only 4 years of follow-up(13).

The U-shaped association for SCD observed in this prospective cohort of women is consistent with the results in another prospective study of men. In the Physicians’ Health Study, men who consumed light-to-moderate amounts of alcohol (2-6 drinks/week) had up to an 80% lower risk of SCD compared to nondrinkers, while men with higher intake (≥2 drinks/day) had no significant increase in risk(9). Similar to the present study, associations for non-sudden CHD events differed, and higher levels of alcohol intake associated with lower risks of non-fatal MI and non-sudden CHD death. However, despite these consistencies, several earlier prospective cohort studies did not observe a reduction in SCD risk associated with moderate alcohol intake despite observing reductions in other CHD endpoints(6-8). In these early studies, the number of SCD cases was relatively small, between 58 and 117 cases, which may have limited the ability to detect significant reductions in risk. Furthermore, tests for non-linear associations were not conducted, and moderate alcohol intake included intakes as high as 40 g/day (3-4 drinks per day) in some of these studies(7, 9).

In contrast to other prospective studies(5,6), we found no significant increase in SCD risk at any level of alcohol intake; however, the range of alcohol intake among these female nurses was truncated, with few women (4%) reporting moderate-to-heavy consumption (>30 g or >2 drinks/day), and even fewer (<1%) reporting more extreme intake (>50 g/day). Therefore, we could not assess the hazards of heavy alcohol consumption on SCD risk. Among men without pre-existing CHD, heavy drinking was associated with greater risk of sudden death(6,20). We did not observe an increased risk among women with pre-existing CHD, although power to detect an association was limited. Alternatively, while CHD underlies the majority of SCD events in men, the etiology of SCD among women is more likely to be from other causes(21), and therefore the interaction between alcohol and pre-existing disease may not hold among women.

In experimental studies, alcohol exerts proarrhythmic effects, including inhibition of cardiac sodium channel gating, increased ventricular repolarization, increased heart rate, decreased heart rate variability and increased sympathetic activity(22-25). However, alcohol also has beneficial effects on pathways involved in atherosclerosis progression, including plaque rupture(26), lipids(26), inflammation(27), and hemostatic factors(28), through which it may lower risk of coronary disease and SCD. Additionally, moderate alcohol intake was positively associated with blood concentrations of marine n-3 fatty acids(29), which have anti-arrhythmic properties and are strong predictors of SCD risk(30). The differential dose-response of alcohol with sudden compared to non-sudden cardiac events suggests potentially different biological effects of alcohol at various doses. Alcohol intake at low-to-moderate levels may lower risk of both coronary disease and SCD through processes related to atherosclerosis, while at higher doses, the proarrhythmic effects of alcohol may nullify any potential benefits for SCD.

This study has several additional limitations that warrant discussion. Although this is the largest prospective study to examine the relationship between alcohol and SCD in women, we were unable to assess the role of drinking patterns, and specifically binge drinking, on risk of SCD. Binge drinking, but not usual alcohol intake, was associated with increased risk of SCD in men(7), but data among women are scarce. Drinking frequency modifies the association between heavy alcohol intake and risk of coronary disease. In a recent meta-analysis, heavy alcohol drinkers who drank more frequently had a lower risk of CHD, while irregular and binge drinkers had an elevated risk(31). However, the prevalence and importance of binge drinking may be greater in men than in women(32). Therefore, more research is needed to understand the role of drinking patterns in relation to SCD and to evaluate potential effect modification of this relationship by gender.

These women may consume alcohol in a more healthful pattern. In survey data from the general US population, 6% of women age 20 or older reported consuming ≥2 drinks/day on average(33), and between 2.3% and 5.0% of women 45 and older report drinking ≥7 drinks/week on average(34). In this population, more women consume ≥1 drink/day (11%), but fewer women consume >2 drinks/day (4%). Although we attempted to control for confounding by healthy lifestyle, residual confounding remains possible. Furthermore, the homogeneity of this cohort of US female registered nurses may limit the generalizability of these findings. However, this homogeneity also minimizes variation in socioeconomic status and other potential confounders. We also had limited power to detect plausible interactions by incident CHD or to explore potential differing associations by beverage type, particularly for subcategories such as red versus white wine where sparse data precluded meaningful analyses. Finally, drug therapy evolved drastically throughout this study. For example, women were enrolled during in an era of Type I antiarrhythmic drugs and had a much lower prevalence of CVD medications, like ACE inhibitors or beta-blockers. Unfortunately, we do not have comprehensive data on drug therapies, in particular during the early follow-up years, and could not control for these factors adequately.

An important strength of these data is the repeated assessment of alcohol intake, which allowed us to explore relatively short-term effects of alcohol, which may be the most biologically relevant period for arrhythmias and SCD. We separated the former drinkers from abstainers using the updated alcohol data, minimizing any potential “sick quitter” bias to the extent possible. However, when we included former drinkers in the referent non-drinking category, the results were similar. Additionally, the categories of alcohol intake in previous studies included a relatively wide range of intake (i.e. 2-6 drinks/day). The details on alcohol intake in the FFQ used in this analysis allowed for the calculation of alcohol in grams per day, which enhanced the precision of our exposure.

Conclusions

This study supports previous evidence that light-to-moderate alcohol consumption is not associated with greater risk of sudden death, and may provide benefit in prevention of sudden death. Current recommendations for alcohol intake suggest that women consume no more than 1 drink per day. When our results are taken in context of the prior literature on the role of alcohol and risk of chronic disease in women, intake of up to 1 drink per day is related to a lower risk for SCD, coronary heart disease, stroke and congestive heart failure. Higher intake of alcohol may be associated with lower risk of overall coronary disease, but also is associated with greater risk of atrial fibrillation(35), stroke,(2) and cancer(36). Advice to consume any amount of alcohol must balance the potential benefits against potential risks related to other chronic diseases. These data indicate that light-to-moderate alcohol intake may be considered part of a healthy lifestyle for overall chronic disease prevention, including prevention of SCD, when consumed responsibly, and when not contraindicated by other factors.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: The study was supported by an Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association to Dr. Albert and by Grants CA-87969, HL-34594, HL-03783, and HL-068070 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CHD

Coronary Heart Disease

- SCD

Sudden Cardiac Death

- FFQ

food frequency questionnaire

- RR

Relative risk

- CI

Confidence interval

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Corrao G, Rubbiati L, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Poikolainen K. Alcohol and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2000;95:1505–1023. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951015056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynolds K, Lewis B, Nolen JD, Kinney GL, Sathya B, He J. Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;289:579–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh CR, Larson MG, Evans JC, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk for congestive heart failure in the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:181–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ettinger PO, Wu CF, De La Cruz C, Jr., Weisse AB, Ahmed SS, Regan TJ. Arrhythmias and the “Holiday Heart”: alcohol-associated cardiac rhythm disorders. Am Heart J. 1978;95:555–62. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(78)90296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyer AR, Stamler J, Paul O, et al. Alcohol consumption, cardiovascular risk factors, and mortality in two Chicago epidemiologic studies. Circulation. 1977;56:1067–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.6.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wannamethee G, Shaper AG. Alcohol and sudden cardiac death. Br Heart J. 1992;68:443–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.68.11.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozarevic D, Demirovic J, Gordon T, Kaelber CT, McGee D, Zukel WJ. Drinking habits and coronary heart disease: the Yugoslavia cardiovascular disease study. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;116:748–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kittner SJ, Garcia-Palmieri MR, Costas R, Jr., Cruz-Vidal M, Abbott RD, Havlik RJ. Alcohol and coronary heart disease in Puerto Rico. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:538–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert CM, Manson JE, Cook NR, Ajani UA, Gaziano M, Hennekens CH. Moderate alcohol consumption and the risk of sudden cardiac death among US male physicians. Circulation. 1999;100:944–950. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scragg R, Stewart A, Jackson R, Beaglehole R. Alcohol and exercise in myocardial infarction and sudden coronary death in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:77–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Fox N. Moderate alcohol consumption and primary cardiac arrest. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:499–503. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hennekens CH, Rosner B, Cole DS. Daily alcohol consumption and fatal coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;107:196–200. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and the risk of coronary disease and stroke in women. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:267–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808043190503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovannucci E, Colditz G, Stampfer MJ, et al. The assessment of alcohol consumption by a simple self-administered questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:810–817. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert CM, Chae CU, Grodstein F, et al. Prospective study of sudden cardiac death among women in the United States. Circulation. 2003;107:2096–101. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065223.21530.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinkle LE, Thaler HT. Clinical classification of cardiac deaths. Circulation. 1982;65:457–464. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–69. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Statist Med. 1989;8:551–561. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenland S, Michels KB, Robins JM, Poole C, Willett WC. Presenting statistical uncertainty in trends and dose-response relations. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:1077–86. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon T, Kannel WB. Drinking habits and cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1983;105:667–73. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chugh SS, Chung K, Zheng ZJ, John B, Titus JL. Cardiac pathologic findings reveal a high rate of sudden cardiac death of undetermined etiology in younger women. Am Heart J. 2003;146:635–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein G, Gardiwal A, Schaefer A, Panning B, Breitmeier D. Effect of ethanol on cardiac single sodium channel gating. Forensic Sci Int. 2007;171:131–5. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossinen J, Viitasalo M, Partanen J, Koskinen P, Kupari M, Nieminen MS. Effects of acute alcohol ingestion on heart rate variability in patients with documented coronary artery disease and stable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:487–91. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00790-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossinen J, Sinisalo J, Partanen J, Nieminen MS, Viitasalo M. Effects of acute alcohol infusion on duration and dispersion of QT interval in male patients with coronary artery disease and in healthy controls. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22:591–4. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960220910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupari M, Koskinen P. Alcohol, cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death. Novartis Found Symp. 1998;216:68–79. doi: 10.1002/9780470515549.ch6. discussion 79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Breslow JL, et al. Moderate alcohol intake, increased levels of high-density lipoprotein and its subfractions and decreased risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1829–1834. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312163292501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pai JK, Hankinson SE, Thadhani R, Rifai N, Pischon T, Rimm EB. Moderate alcohol consumption and lower levels of inflammatory markers in US men and women. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:113–20. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridker PM, Vaughan DE, Stampfer MJ, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH. Association of moderate alcohol consumption and plasma concentration of endogenous tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Am Med Assoc. 1994;272:929–933. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520120039028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.di Giuseppe R, de Lorgeril M, Salen P, et al. Alcohol consumption and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in healthy men and women from 3 European populations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:354–62. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albert CM, Campos H, Stampfer MJ, et al. Blood levels of long-chain n-3 fatty acids and the risk of sudden death. New Engl J Med. 2002;346:1113–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bagnardi V, Zatonski W, Scotti L, La Vecchia C, Corrao G. Does drinking pattern modify the effect of alcohol on the risk of coronary heart disease? Evidence from a metaanalysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:615–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.065607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tolstrup J, Jensen MK, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Mukamal KJ, Gronbaek M. Prospective study of alcohol drinking patterns and coronary heart disease in women and men. Bmj. 2006;332:1244–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38831.503113.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breslow RA, Guenther PM, Juan W, Graubard BI. Alcoholic beverage consumption, nutrient intakes, and diet quality in the US adult population, 1999-2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:551–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoenborn CA, Adams PF. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2005–2007. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2010;10:1–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conen D, Tedrow UB, Cook NR, Moorthy MV, Buring JE, Albert CM. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. Jama. 2008;300:2489–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen NE, Beral V, Casabonne D, et al. Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:296–305. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]