Abstract

Introduction

Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) is the only FDA approved lytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke. However, there can be complications such as intra-cerebral hemorrhage. This has led to interest in adjuncts such as GP IIb-IIIa inhibitors. However, there is little data on combined therapies. Here, we measure clot lysis for rt-PA and eptifibatide in an in vitro human clot model, and determine the drug concentrations maximizing lysis. A pharmacokinetic model is used to compare drug concentrations expected in clinical trials with those used here. The hypothesis is that there is a range of rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations that maximize in vitro clot lysis.

Materials and Methods

Whole blood clots were made from blood obtained from 28 volunteers, after appropriate institutional approval. Sample clots were exposed to rt-PA and eptifibatide in human fresh-frozen plasma; rt-PA concentrations were 0, 0.5, 1, and 3.15 μg/ml, and eptifibatide concentrations were 0, 0.63, 1.05, 1.26 and 2.31 μg/ml. All exposures were for 30 minutes at 37 C. Clot width was measured using a microscopic imaging technique and mean fractional clot loss (FCL) at 30 minutes was used to determine lytic efficacy. On average, 28 clots (range: 6-148) from 6 subjects (3-24) were used in each group.

Results and Conclusions

FCL for control clots was 14% (95% Confidence Interval: 13-15%). FCL was 58% (55-61%) for clots exposed to both drugs at all concentrations, except those at an rt-PA concentration of 3.15 μg/ml, and eptifibatide concentrations of 1.26 μg/ml (Epf) or 2.31 μg/ml. Here, FCL was 43% (36-51) and 35% (32-38) respectively. FCL is maximized at moderate rt-PA and eptifibatide concentration; these values may approximate the average concentrations used in some rt-PA and eptifibatide treatments.

Introduction

Currently the only FDA approved therapy for acute ischemic stroke is the intra-venous administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA)[1]. However, this therapy has substantial side effects such as intra-cerebral hemorrhage (ICH)[2]. This has led to much interest in other potential acute stroke therapies such as ultrasound enhanced thrombolysis [3], interventional clot removal [4], and alternative lytic regimens such as combined therapy using rt-PA and GP IIb-IIIa inhibitors [5, 6]. The overall goal is to decrease the ICH rate and increase the efficacy of lytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke.

The use of combination GP IIb-IIIa inhibitors and rt-PA in the treatment of some acute coronary syndromes is well-known [7]. This led to the idea of applying GP IIb-IIIa inhibitors to the treatment of acute ischemic stroke [8, 9]. Recently, Quereshi et al studied combined intra-arterial (IA) reteplase and abciximab in acute ischemic stroke patients [10]. In this dose-escalation pilot trial, patients received 0.5, 1, 1.5 or 2 units of intra-arterial reteplase, along with abciximab (0.25 mg/kg bolus followed by a drip at a rate of 0.125 μg/kg-min). These medications were administered from 3 to 6 hours after stroke symptom onset, and did not increase the rate of hemorrhagic complications. A recent trial of combined eptifibatide and rt-PA (CLEAR) [11] showed no increased clinical efficacy, but was shown to be safe with no increase in the ICH rate, as compared with standard rt-PA lytic therapy. Currently, the CLEAR-ER trial [12] is investigating combined eptifibatide and moderate dose rt-PA in stroke patients presenting within 3 hours of symptom onset.

Overall, the use of combined eptifibatide and rt-PA is clinically useful in the treatment of myocardial infarction (MI), and is promising as a treatment for acute ischemic stroke. However, there is little in vitro data on the lytic efficacy of such combined therapy to guide current and future clinical trials. In this work, we present the results of measurements of the lytic efficacy of combined rt-PA and eptifibatide treatment in an in vitro human clot model. Our overall hypothesis is that there is a range of rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations that maximize in-vitro human clot lysis. The correspondence between the in vitro data and the average expected concentrations of rt-PA and eptifibatide, using a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model, is used to compare these results with clinical trials of this combined therapy.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of rt-PA, eptifibatide and human plasma

The rt-PA was obtained from the manufacturer (rt-PA, Activase®, Genentech, San Francisco, CA) as a lyophilized powder. Each vial was mixed with sterile water to a concentration of 1 mg/ml as per manufacturer’s instructions, aliquoted into 1.0 ml centrifuge tubes (Model 05-408-13, Fisher Scientific Research, Pittsburgh, PA), and stored at −80°C. The enzymatic activity of rt-PA is stable for years when stored in this fashion [13, 14]. Eptifibatide was obtained (Integrilin®, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Cambridge, MA) as a solution at a concentration of 2 mg/ml. The drug was stored at 4-5°C to prevent degradation, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Human fresh-frozen plasma (hFFP) was procured from a blood bank in 250-300 ml units. Each unit was briefly thawed, aliquoted into 50 ml polypropylene centrifuge tubes (Model 05-538-68, Fisher Scientific Research, Pittsburgh, PA), and stored at −80°C. Aliquots of rt-PA, plasma, and eptifibatide were allowed to thaw for experiments; the remaining amounts discarded following completion of each experiment.

Production of blood clots

Human whole blood was obtained from healthy volunteers, predominantly drawn from among the investigators’ colleagues, by sterile venipuncture following local Institutional Review Board approval and written informed consent. The only exclusion criterion was the use of aspirin within 72 hours of the blood draw. Blood from a total of 28 subjects was used in these studies. The average age of these volunteers was 37 (6) years (mean and standard deviation), ranging from 28 to 51 years of age. There were 19 men and 9 women; and there were 2 African-Americans, 2 Asians, and 24 Caucasians.

Clots from a given donor were randomly allocated to treatment with combined rt-PA and eptifibatide lysis using the following rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations; 0, 0.63, 1.05, or 1.26 μg/ml of eptifibatide, and 0, 0.5, 1.0, or 3.15 μg/ml of rt-PA. Data from previous measurements of rt-PA lysis were included as well to improve the precision of mean FCL values for rt-PA alone treated clots. The overall numeric goal was at least 10 clots from 3 subjects for each treatment group; this was found to be adequate to determine differences among treatment groups in our previous work [15, 16]. Overall, these numbers are also comparable to those in in vitro clot lysis experiments by others [17, 18]. The total number of clots used in these experiments was 503.

Samples of 1-2 ml were placed in sterile glass tubes (3ml, VWR, Batavia, IL) and allowed to form clots in and around a small diameter (~600 μm) micropipette (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ; 20λ) through which a segment of 7-0 silk suture (Ethicon Industries, Cornelia, GA) had been threaded. This is similar to clot production methods used in imaging studies by Winter [19] and Yu [20]. The clots were incubated for three hours at 37°C, and refrigerated at 5°C for 3 days ensuring maximal clot retraction, lytic resistance and stability [21-23]. Before each experiment, the micropipette was removed to produce a cylindrical clot adherent to the suture. The clot was typically 5-8 μl in volume and approximately 300 μm in width. At this size the clots were similar in diameter to the intracerebral segments of the middle cerebral arteries (80 to 840 μm in diameter) or other cerebral vessels such as the recurrent artery of Heubner and its perforators (643 ± 237 μm in diameter) [24, 25].

Visualization of the clot

For each experiment, the clot attached to the suture was placed in a clean micropipette (Drummond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA; 200 μl), and inserted into a U-shaped sample holder composed of hollow luer lock connectors and silicone tubing (Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL; outer diameter 0.125”). The sample holder was placed in an acrylic water tank with a microscope, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the experimental apparatus.

Water in the tank was maintained at a temperature of 37±1°C during all experiments using a heating element (Hagen, Mansfield, MA; 50 W). The tank was placed over the objective of an inverting microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) to visualize the clot. The field of view in the image was 340 μm × 260 μm (640 pixels × 480 pixels). The entire apparatus was placed on top of a vibration isolation table (Newport, Irvine, CA; XL-G) for mechanical isolation [26]. Images were recorded at 6 frames/minute using a CCD camera (Hitachi, Woodbury, NY; KP-M1A), and data was stored for later analysis on a computer (Dell, Round Rock, TX; Intel Pentium). A complete description of the imaging apparatus has been previously provided [26, 27].

Determination of lytic efficacy

Light intensity transmitted through the sample clot is reduced with increased clot thickness or clot density. The CCD camera records image light intensity I(x,z) at each pixel (x,z). By analyzing the light intensity in each pixel, the clot edges can be identified, thus enabling measurement of clot width.

An image from the CCD camera was stored on a desktop computer for each frame as a function of time. The average clot width (CW) was then calculated, using a computer program written in Matlab 6.5 R13 (Mathworks, Inc., Natwick, MA). First, the spatial gradient of the light intensities ∂I(x,z)/∂x was calculated for each row (fixed z) of pixels. The positions of the two clot-plasma interfaces were determined via an edge-detection routine that finds the values of x = (x1, x2) for each z such that ∂I/∂x(x1,2, z)≥Γ, where Γ is a constant. A Γ of 2.5 is sufficient to detect well-defined clot edges. The width W(z) of the clot at each z was then W(z)=|x1-x2|. The average CW for each image was calculated by averaging the width over all z values. The clot width data were subsequently corrected for the finite suture size used in these experiments. This yields the expression

| (1) |

where CWCorrected is the value of the total clot width adjusted for the finite suture width SW. The average suture width for these experiments was found to be 95±15 μm, based on 252 samples of the 7-0 suture. The data were then normalized to the initial value of CWCorrected during the first minute (six frames; ), yielding the expression

| (2) |

Note that CWNORM(t) is equal to 1 at time t equal to zero, and becomes equal to zero if the clot is totally lysed thus leaving only the suture contributing to the sample width. This parameter is averaged for all clots in a given treatment group. The fractional clot loss (FCL, expressed as %) is then defined as

| (3) |

where CWNORM(30 min) is the average normalized clot width over the final minute of treatment, as determined from Equation (2). Note that as a given sample clot is imaged 6 times per minute, there are 6 measurements for each clot trial.

Experimental Protocol

The rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations values used in these experiments [28-31] are comparable to those used in humans. For example; in the work of Tcheng et al [31], it was shown that platelet receptor occupancy by eptifibatide was approximately 80% for eptifibatide concentrations ranging from about 1.3 to 2.3 μg/ml. GPIIb-IIIa platelet receptor occupancy of 80% was shown by Yasuda et al in an in vivo canine stenotic coronary artery model to prevent vascular re-occlusion in thrombolysis [32]. Similarly, Seifried et al [28] found steady-state concentration values for rt-PA ranging from approximately 2.2 to 3.3 μg/ml were effective in treating acute myocardial infarction. Therefore, the range of rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations used in this study is comparable to those found to be useful in clinical practice, thus motivating the values used here.

Individual trials began by slowly injecting 1 ml of hFFP (control), or 1 ml of hFFP containing rt-PA, eptifibatide, or both (all other trials) into the sample holder. At time t equal to zero, the solution was in contact with the clot. Removing the syringe exposed the ends of the sample holder to atmospheric pressure, and the clot surface to a static fluid column. Clots were exposed to a specific treatment regimen for 30 minutes; previous studies have shown that the majority of thrombolysis occurs within a 30 minute window [33-35].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean values with standard deviations. The 95% confidence limits were calculated for treatment groups using SAS v8.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The error bars for the computed average plasma concentrations of rt-PA and eptifibatide were estimated using propagation of errors (see Appendix).

Pharmacokinetic Model

Motivation

The aim of this study is to determine the approximate range of rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations that maximize in vitro human clot lysis. Although this is potentially useful information, it would be helpful to correlate the average concentrations of these two drugs in patients undergoing rt-PA and eptifibatide treatment, with those values found to maximize lysis from this study. A model is needed that can calculate the average expected drug concentration in an individual as a function of; (1) the detailed dosing parameters of rt-PA and eptifibatide used in the treatment, and (2) the average pharmacokinetic parameters of the drug for the population.

Although there are numerous studies that determine the pharmacokinetic parameters for both rt-PA and eptifibatide, there are none that describes the desired model. For example, Gilchrist et al [30] measured the plasma concentration of eptifibatide in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for various dosing regimens of eptifibatide. They described their results using a two-compartment model, and estimated the pharmacokinetic parameters of the drug from their data. However, their model is not generalizable to other eptifibatide dosing regimens differing from those studied in their interesting work. This motivated the development here of a more general model of rt-PA and eptifibatide behavior in an average patient.

Model Development

The behavior of both rt-PA [36] and eptifibatide [30] are well-approximated by two-compartment pharmacokinetics. Such drugs [37] exhibit an initial rapid ‘redistribution phase,’ whereby drug moves from the central (vascular) compartment to the peripheral compartment (well-perfused organs or tissues). This is then followed by a slower ‘elimination phase,’ whereby the drug is eliminated from the body. If a drug is given as a bolus dose followed by an infusion, the plasma concentration Cp (t) as a function of time t can be written as [38],

| (4) |

where CSS is the “steady state” concentration, and the parameters CSS, X1, X2, α, and β depend on the particular dosing regimen and pharmacokinetic properties of the drug (see Appendix for more detail). If the total infusion time for a given drug is T, then the average plasma concentration CPAVG during the infusion time can be written as,

| (5) |

Equation 5 can then be used to estimate the average drug concentration for rt-PA and eptifibatide for various clinical trials, using the known pharmacokinetic parameters for these drugs.

Table 1 exhibits the estimated average values for the pharmacokinetic parameters of both rt-PA [36, 39] and eptifibatide [30, 40-42], as found in the literature. The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by determining the average of those values reported in the specific references for each drug. An estimated standard error was calculated from these referenced values, and is shown in parentheses in the table. These parameters, along with the dosing regimens of a given clinical trial (see Table 3), can then be used to calculate CPAVG (eptifibatide) and CPAVG (rt-PA) to compare with the concentration values of eptifibatide and rt-PA used in this study. A routine was written in Matlab (Matlab 6.5 R13, Mathworks, Inc., Natwick, MA) to calculate these CPAVG values based on Tables (1) and (3), and equation (5).

Table 1.

Average pharmacokinetic parameters as calculated for a 70 kg person for rt-PA and eptifibatide

| Pharmacokinetic Parameter | rt-PA | Eptifibatide |

|---|---|---|

| Apparent Volume of Distribution VC (L) | 7.7 (0.4) | 9.8 (4.2) |

| Clearance Cl (L/min) | 0.74 (0.08) | 0.074 (0.015) |

| Redistribution Half-life t1/2α (min) | 4.3 (0.4) | 19 (6) |

| Elimination Half-life t1/2β (min) | 43 (10) | 202 (83) |

Table 3.

Drug dosage parameters (bolus and infusion) of rt-PA and eptifibatide

| Clinical Trial |

rt-PA | Eptifibatide | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolus | Infusion | Bolus | Infusion | |

| IMPACT AMI |

15 mg | 0.75 mg/kg in 30 min, then 0.5 mg/kg in 60 min |

180 μg/kg |

0.75 μg/kg over 24 hrs |

| CLEAR (Tier 1) |

15% of 0.3 mg/kg |

85% of 0.3 mg/kg over 1 hr | 75 μg/kg | 0.75 μg/kg-min for 2 hrs |

| CLEAR (Tier 2) |

15% of 0.45 mg/kg |

85% of 0.45 mg/kg over 1 hr | 75 μg/kg | 0.75 μg/kg-min for 2 hrs |

| CLEAR –ER | 15% of 0.6 mg/kg |

85% of 0.6 mg/kg over 1 hr | 135 μg/kg |

0.75 μg/kg-min for 2 hrs |

Results

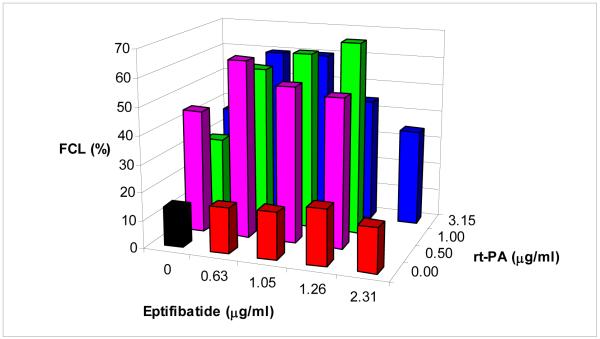

Figure 2 exhibits the fractional clot loss (FCL) for all of the treatment groups. The error bars are not shown for clarity. For clots exposed to rt-PA alone, FCL increases from 14 % (95% Confidence Interval: 13-15%) for both rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations of 0 μg/ml (control) to 38 % (95% CI: 32-44%) at an rt-PA concentration of 0.5 μg/ml. There is no significant change in FCL at higher rt-PA concentrations in this group. Similarly for clots exposed to eptifibatide alone, FCL increases to 17% (95% CI: 15-19%) for an eptifibatide concentration equal to 1.05 μg/ml as compared with control treated clots. There is no significant change in FCL at higher eptifibatide concentrations. In addition, Table 2 lists the average FCL values along with the standard deviation, number of subjects, and number of clots for each specific trial. Again, note that for each clot, there are 6 measurements of FCL over the final minute of clot lysis.

Figure 2.

Fractional clot loss (FCL) as a function of rt-PA and eptifibatide concentration.

Table 2.

Drug dosage parameters (bolus and infusion) of rt-PA and eptifibatide for clinical trials of combined rt-PA and eptifibatide thrombolysis.

Mean FCL (%) with standard deviations, 95% Confidence Intervals, Number of subjects (Nsubject) and Number of clots (Nclot) for the combined rt-PA and eptifibatide clot lysis measurements.

| Eptifibatide Concentration (μg/ml) |

rt-PA Concentration (μg/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 3.15 | |

| 0 | (FCL) 14% (11) 95% CI [13-15%] (Nsubject/Nclot) 21/148 |

38% (29) [23-44%] 6/14 |

30% (23) [27-33%] 8/42 |

36 %(26) [34-38%] 24/128 |

| 0.63 | 16% (7) [14-18%] 4/15 |

60% (30) [53-67%] 4/12 |

58 % (25) [52-64%] 4/11 |

58% (35) [51-65%] 5/15 |

| 1.05 | 17% (11) [15-19%] 3/14 |

55% (25) [50-60%] 4/13 |

60% (27) [53-67%] 4/11 |

60% (22) [54-66%] 5/15 |

| 1.26 | 17% (20) [13-34%] 3/11 |

55% (23) [49-61%] 3/10 |

61% (25) [54-68%] 4/11 |

43% (30) [37-50%] 3/12 |

| 2.31 | 16% (19) [12-20%] 3/15 |

-- | -- | 35% (13) [32-38%] 3/11 |

For clots treated with both eptifibatide and rt-PA, FCL increases substantially over that of clots treated with rt-PA or eptifibatide alone. For clots treated with rt-PA at a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml, and eptifibatide at 0.63 μg/ml, FCL was 60% (95% CI: 53-67%). The lowest FCL in clots treated with both drugs was for those exposed at 2.31 μg/ml of eptifibatide and 3.15 μg/ml of rt-PA; this yielded an FCL of 35% (95% CI: 32-38%). Overall, clots treated with eptifibatide and rt-PA exhibited an average FCL of 58% (95% CI: 55-61%), excluding those treated with rt-PA at 3.15 μg/ml and eptifibatide at 1.26 μg/ml or 2.31 μg/ml.

Figure 3 shows the average estimated plasma concentrations of eptifibatide and rt-PA, as computed using equation (5), using the reported dosing regimens in trials such as CLEAR [11], CLEAR-ER [12] and IMPACT-AMI [43]. It should be noted that the value computed for CPAVG(rt-PA) for the IMPACT-AMI uses only the initial rt-PA infusion rate of 0.75 mg/kg over 30 minutes; therefore this value is likely overestimated. The shaded area corresponds to the concentration values of eptifibatide and rt-PA for which FCL is maximized (Figure 2). Note that the estimated values for the CLEAR-ER and IMPACT-AMI trials [12, 43] lie in the region where FCL is maximized. The error bars were obtained by using propagation of errors to estimate the variability of the average concentration values (see Appendix).

Figure 3.

Estimated average plasma concentrations for eptifibatide and rt-PA during drug infusion for various clinical trials as calculated from the pharmacologic model. The drug doses used assume a 70 kg human. The shaded region denotes the range of concentrations where FCL is maximized.

Discussion

It has been shown that the lytic efficacy of combined rt-PA and eptifibatide treatment is greater than that of rt-PA or eptifibatide alone in this in vitro human clot model. Clot lysis, as measured by the FCL values, is maximal overall for nonzero rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations with maximal effect beginning at 1 μg/ml, and 1.05 μg/ml respectively with the exception of 3.15 μg/ml (rt-PA) and the two highest eptifibatide concentrations (1.26 and 2.31 μg/ml). FCL is significantly reduced at these higher concentrations, as compared with the more intermediate values. A two-compartment pharmacokinetic model was used to estimate the mean plasma concentrations of these drugs for various clinical treatments, based on their published dosing regimens. It was shown that the estimated values for CPAVG (rt-PA) and CPAVG (eptifibatide) for some clinical trials and treatment regimens lie within the range of concentrations that maximize lytic efficacy, as predicted by the in vitro data presented here. This combined approach of in vitro lysis measurements and pharmacokinetic modeling may be useful in planning future clinical trials of combined lytic therapy.

Others have measured the lytic efficacy of combined rt-PA and GP IIb-IIIa inhibitors. Collet et al [44] measured the progression of the “lytic front” in a thin clot model; the clots were exposed to rt-PA and eptifibatide. They prepared “platelet rich” and “platelet poor” clots in their experiment and microscopically measured the progress of the lytic front. Clots were exposed to an rt-PA concentration of 0.3 μg/ml and an eptifibatide concentration of 0.8 μg/ml; these concentrations are comparable to those used in the current work. They found that the rate of progression of the lytic front increased from 2.8 μm/min to 4.6 μm/min in platelet poor clots, and from 1.2 to 4.1 μm/min in platelet rich clots. Interestingly, Atar et al [45] found little difference in the percent mass loss for human whole-blood clots exposed to rt-PA (33±9%) and rt-PA plus the GP IIb-IIIa inhibitor tirofiban (28±4%) for 30 minutes. However, the rt-PA concentration was rather large at 20 μg/ml; the tirofiban concentration used was 0.15 μg/ml. Meunier et al [16] found that FCL in human whole-blood clots increased from 16% to 29% with 30 minutes of rt-PA and rt-PA with eptifibatide treatment respectively. The rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations were 3.15 μg/ml and 2.31 μg/ml in their work. It should be noted that the FCL values were not corrected for the finite suture width in their work, thus likely underestimating the amount of clot lysis. In addition, there is some clot lysis evident even in the control data (14%). This is likely due to the endogenous t-PA and plasminogen that is present in normal human plasma [46]. Overall, other groups have found that combined rt-PA and eptifibatide treatment increase clot lysis over rt-PA treatment alone.

It is notable that the region of maximal lysis (shaded area of Fig. 3), as predicted by the in vitro work here, overlaps the calculated CPAVG values for eptifibatide and rt-PA of a successful clinical trial IMPACT-AMI [43]. In this trial, the investigators observed more complete reperfusion at 90 minutes in the affected coronary artery (TIMI 3 flow in 66% of treated patients) compared with placebo (39%) in acute MI patients treated with combined eptifibatide and rt-PA. This compares with TIMI 3 flow rates in 45 to 49% in AMI patients treated with rt-PA alone in other trials [47]. Conversely, the CPAVG values for CLEAR do not fall within this region, although a direct comparison is approximate at best as CLEAR was primarily a safety trial. In CLEAR, the therapy for both dose tiers was found to be safe with no increase in the ICH rate as compared with standard NINDS rt-PA therapy. There was no improvement in neurologic outcome over the standard therapy [11]. As shown in Figure 3; neither tier 1 nor tier 2 dosing of the combined eptifibatide and rt-PA therapies are within the region of maximal lysis. In contrast, the values for the CLEAR-ER trial lie within the maximal lysis region, suggesting that the values of CPAVG (eptifibatide) and CAVGP (rt-PA) for CLEAR-ER are likely to maximize clot lysis. For comparison, using the standard NINDS dosing of rt-PA for a 70 kg person in Equation (5) yields a CPAVG(rt-PA) of 0.95 μg/ml. Although certainly not conclusive, the correspondence of clinical efficacy (IMPACT-AMI) or lack thereof (CLEAR) of these clinical trials with whether or not their predicted values of CPAVG (eptifibatide) and CPAVG (rt-PA) lie within the maximal lysis zone is suggestive. Overall, this method of comparing predicted values of CPAVG for rt-PA and eptifibatide with the range of concentrations shown to maximize in vitro lytic efficacy may prove useful in planning future clinical trials of lytic therapy.

An interesting finding in this data is that FCL for the highest rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations is lower than that of the more intermediate concentrations. We speculate that an explanation may lie in the mechanism of action of these two drugs. As is known, rt-PA acts predominantly on the fibrin mesh of the clot, cleaving this into fibrin fragments thus causing clot lysis. Eptifibatide blocks the GP IIb-IIIa receptor in platelets thus reducing platelet adhesion to fibrin and platelet-platelet interaction and binding. As the sample clot lyses, clot fragments are released that contain active sites for both rt-PA and eptifibatide binding. However, any lysis occurring on these smaller fragments does not decrease FCL for the primary sample clot, but may, “soak up” available eptifibatide, and rt-PA and plasmin created in the hFFP by the rt-PA. If these clot fragments are more numerous and/or smaller at the higher drug concentrations, this may reduce the amount of drug available to lyse the primary sample clot thus decreasing FCL. Particularly if the clot fragments are smaller, this would increase the surface to volume ratio and potentially increase the number of binding sites per unit volume on each clot fragment for rt-PA and eptifibatide. Support for this highly speculative concept can be found in the work of Collet et al [44] in which clots treated with rt-PA alone yielded fragments with an average diameter of 60 μm, whereas fragment from clots treated with rt-PA and eptifibatide were 8 to 10 μm in size.

Another interesting observation is that there is little variation in FCL for the range of rt-PA and eptifibatide concentrations that maximize FCL. One can speculate that for these values, the enzymatic reactions that are responsible for clot lysis are limited by the amount of substrate. Overall, there is a limited amount of clot available for lysis, and in the case of rt-PA there is a finite amount of plasminogen available. Thus no further increase in FCL can be seen in this concentration regime. However, is should be pointed out that these mechanisms are speculative.

The primary limitations of this work are first, the in vitro clots are not subjected to blood flow and are therefore in a different environment than that of an in-situ thrombus. Second, the clots are human whole blood clots and are likely different in composition to acute arterial thrombus. However such aged clots are very resistant to clot lysis, as shown by others [21-22], thus the lysis model here is conservative in that we are likely underestimating lytic efficacy. Third, these clots are made from the blood of healthy donors thus limiting the applicability of the results here to the more chronically ill acute stroke or MI population. Additionally, it is not known if the donors had potentially confounding blood disorders such as thrombophilia, bleeding tendencies, or if they were taking other medications that could alter clot formation and fibrinolysis such as birth control pills or other hormones. In addition, the two-compartment kinetics used in deriving the pharmacokinetic model is an approximation to the clinical behavior of rt-PA and eptifibatide. Finally, the pharmacokinetic parameters shown in Table 1 are the average values of those references found by the authors in the literature; these values may not include all such published studies. As a result, the average concentrations calculated with this model must be considered approximations, and not definitive average values.

It is possible that rt-PA concentrations less than 0.5 μg/ml and eptifibatide concentrations less than 0.63 μg/ml for eptifibatide could maximize FCL and in vitro clot lysis. As there is no significant variation in FCL for clots treated with both drugs except at the highest concentrations (Figure 2), it is not known at what concentrations FCL begins to increase over that of clots treated with rt-PA or eptifibatide alone. In a graphical sense, the left and lower boundary of the shaded region in Figure 3 may extend to lower concentrations than is currently indicated.

It has been shown in this work that combined rt-PA and eptifibatide exhibit greater lytic efficacy in an in vitro human clot model than either drug alone. In addition, a range of concentrations which maximizes in vitro lytic efficacy was determined. A pharmacokinetic model was derived to calculate the average plasma concentrations of eptifibatide and rt-PA for a given dosing regimen, allowing an approximate comparison of the drug concentrations used in the in vitro work with those calculated to occur for various clinical trials such as CLEAR and IMPACT-AMI. Such an approach may prove useful in planning and interpreting future clinical trials of combined eptifibatide and rt-PA lytic therapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NINDS through K02-NS056253 and 3P50-NS044283-06S1. The authors gratefully acknowledge useful conversations with Dr. Opeolu Adeoye and the members of the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Team.

Appendix: Derivation of Pharmacokinetic Model

Using the notation and derivations of RD Schoenwald [38], the plasma concentration CP(t) for time t for a drug that obeys two-compartment pharmacokinetics can be written as

| (A1) |

where the terms CSS, X1, and X2, depend on the pharmacokinetic parameters for the given drug. It is assumed that the drug is given as a bolus at time zero followed by a continuous infusion at a constant rate.

The parameters in (A1) can then be written as,

| (A2a) |

where CSS is the “steady state” concentration, R is the infusion rate, VC is the apparent volume of distribution in the central compartment, and k10 is the elimination rate constant for the drug. This expression can be re-written in terms of the whole body clearance Cl using the expression

| (A2b) |

The quantities X1 and X2 can be written as

| (A2c) |

| (A2d) |

where B is the bolus dose of the drug, and α and β are the time constants for redistribution and elimination of the drug respectively. These time constants are related to the half-lives of the drug through the expressions,

| (A3a) |

| (A3b) |

where t1/2(α) and t1/2(β) are the half-lives of drug redistribution and elimination respectively.

If the infusion of the drug is given for a total time T, the average plasma concentration over this time can be written as

| (A4) |

Evaluating this expression yields equation (5).

One can estimate the error in CPAVG by realizing that the largest contribution to the average plasma concentration is from the CSS term in Eq. (A1). Using equations (A2a) and (A2b), CSS can be written as

| (A5) |

Given that the infusion rate R is constant, and recalling from propagation of errors that

| (A6) |

one can write

| (A7) |

recalling the assumption that the majority of the error in CPAVG arises from the error in CSS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adams HP, Jr., Brott TG, Furlan AJ, Gomez CR, Grotta J, Helgason CM, Kwiatkowski T, Lyden PD, Marler JR, Torner J, Feinberg W, Mayberg M, Thies W. Guidelines for thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke: a supplement to the guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996;94:1167–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NINDS Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. NEJM. 1995;333:1581–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexandrov AV, Molina CA, Grotta JC, Garami Z, Ford SR, Alvarez-Sabin J, Montaner J, Saqqur M, Demchuk AM, Moye LA, Hill MD, Wojner AW. Ultrasound-enhanced systemic thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:2170–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brekenfeld C, Remonda L, Nedeltchev K, Bredow FV, Ozdoba C, Wiest R, Arnold M, Mattle HP, Schroth G. Endovascular neuroradiological treatment of acute ischemic stroke: Techniques and results in 350 patients. Neurological Research. 2005;27:S29–S35. doi: 10.1179/016164105X35549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pancioli AM, Brott TG. Therapeutic potential of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists in acute ischaemic stroke: scientific rationale and available evidence. CNS drugs. 2004;18:981–8. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams HP, Jr., Brott TG, Furlan AJ, Gomez CR, Grotta J, Helgason CM, Kwiatkowski T, Lyden PD, Marler JR, Torner J, Feinberg W, Mayberg M, Thies W. Guidelines for Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Stroke: a Supplement to the Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 1996;27:1711–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon CP. Evolving management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: update on recent data. The American journal of cardiology. 2006;98:10Q–21Q. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams HP, Jr., Effron MB, Torner J, Davalos A, Frayne J, Teal P, Leclerc J, Oemar B, Padgett L, Barnathan ES, Hacke W, Ab E-III Emergency Administration of Abciximab for Treatment of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: Results of an International Phase III Trial: Abciximab in Emergency Treatment of Stroke Trial (AbESTT-II) Stroke. 2008;39:87–99. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.476648. for the. 10.1161/strokeaha.106.476648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams HP, Jr., Effron MB, Torner J, Davalos A, Frayne J, Teal P, Leclerc J, Oemar B, Padgett L, Barnathan ES, Hacke W. Emergency Administration of Abciximab for Treatment of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: Results of an International Phase III Trial. Abciximab in Emergency Treatment of Stroke Trial (AbESTT-II) Stroke. 2007 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.476648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi AIMD, Harris-Lane PRN, Kirmani JFMD, Janjua NMD, Divani AAPD, Mohammad YMMD, Suarez JIMD, Montgomery MOMD. Intra-arterial Reteplase and Intravenous Abciximab in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: An Open-label, Dose-ranging, Phase I Study. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:789–97. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000232862.06246.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pancioli AM, Broderick J, Brott T, Tomsick T, Khoury J, Bean J, del Zoppo G, Kleindorfer D, Woo D, Khatri P, Castaldo J, Frey J, Gebel J, Jr., Kasner S, Kidwell C, Kwiatkowski T, Libman R, Mackenzie R, Scott P, Starkman S, Thurman RJ. The combined approach to lysis utilizing eptifibatide and rt-PA in acute ischemic stroke: the CLEAR stroke trial. Stroke. 2008;39:3268–76. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.517656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cincinnati U. Study of the Combination Therapy of Rt-PA and Eptifibatide to Treat Acute Ischemic Stroke. 2009. CLEAR-ER NCT00894803. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw GJ, Sperling M, Meunier JM. Long-term stability of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator at −80 C. BMC research notes. 2009;2:117. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaffe GJ, Green GD, Abrams GW. Stability of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108:90–1. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw GJ, Meunier JM, Huang SL, Lindsell CJ, McPherson DD, Holland CK. Ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis with tPA-loaded echogenic liposomes. Thromb Res. 2009;124:306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meunier JM, Holland CK, Pancioli AM, Lindsell CJ, Shaw GJ. Effect of low frequency ultrasound on combined rt-PA and eptifibatide thrombolysis in human clots. Thrombosis research. 2009;123:528–36. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nedelmann M, Brandt C, Schneider F, Eicke BM, Kempski O, Krummenauer F, Dieterich M. Ultrasound-induced blood clot dissolution without a thrombolytic drug is more effective with lower frequencies. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20:18–22. doi: 10.1159/000086122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardig BM, Carlson J, Roijer A. Changes in clot lysis levels of reteplase and streptokinase following continuous wave ultrasound exposure, at ultrasound intensities following attenuation from the skull bone. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2008;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winter P, Shukla H, Caruthers S, Scott M, Fuhrhop R, Robertson J, Gaffney P, Wickline S, Lanza G. Molecular imaging of human thrombus with computed tomography. Acad Radiol. 2005;12(Suppl 1):S9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu X, Song SK, Chen J, Scott MJ, Fuhrhop RJ, Hall CS, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. High-resolution MRI characterization of human thrombus using a novel fibrin-targeted paramagnetic nanoparticle contrast agent. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2000;44:867–72. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200012)44:6<867::aid-mrm7>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis C, Totterman S. Magnetic resonance imaging of deep vein thrombi correlates with response to thrombolytic therapy. Throm Haemost. 1995;73:385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loren M, Garcia Frade LJ, Torrado MC, Navarro JL. Thrombus age and tissue plasminogen activator mediated thrombolysis in rats. Thromb Res. 1989;56:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(89)90009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw GJ, Bavani N, Dhamija A, Lindsell CJ. Effect of mild hypothermia on the thrombolytic efficacy of 120 kHz ultrasound enhanced thrombolysis in an in-vitro human clot model. Thrombosis Research. 2006;117:603–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marinkovic SV, Miliasavljevic MM, Kovacevic MS, Stevia ZD. Perforating branches of the middle cerebral artery: Microanatomy and clinical significance of their intracerebral segments. Stroke. 1958;15:1022–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.16.6.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao X, Yu XJ, Bhattarai B, Li TH, Jin H, Wei GW, Ming JS, Ren W, Jiong C. Microsurgical anatomy of the anterior communicating artery complex in adult Chinese heads. Surgical Neurology. 2006;65:151–61. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng JY, Shaw GJ, Holland CK. In vitro microscopic imaging of enhanced thrombolysis with 120-kHz ultrasound in a human clot model. Acoustic Research Letters Online. 2005;6:25–9. doi: 10.1121/1.1815039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meunier JM, Holland CK, Lindsell CJ, Shaw GJ. Duty Cycle Dependence of Ultrasound Enhanced Thrombolysis in a Human Clot Model. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2007a;33:576–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seifried E, Tanswell P, Ellbruck D, Haerer W, Schmidt A. Pharmacokinetics and haemostatic status during consecutive infusions of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost. 1989;61:497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tardiff BE, Jennings LK, Harrington RA, Gretler D, Potthoff RF, Vorchheimer DA, Eisenberg PR, Lincoff AM, Labinaz M, Joseph DM, McDougal MF, Kleiman NS. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes: prospective analysis from PURSUIT. Circulation. 2001;104:399–405. doi: 10.1161/hc2901.093500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilchrist IC, O’Shea JC, Kosoglou T, Jennings LK, Lorenz TJ, Kitt MM, Kleiman NS, Talley D, Aguirre F, Davidson C, Runyon J, Tcheng JE. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of higher-dose, double-bolus eptifibatide in percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2001;104:406–11. doi: 10.1161/hc2901.093504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tcheng JE, Talley JD, O’Shea JC, Gilchrist IC, Kleiman NS, Grines CL, Davidson CJ, Lincoff AM, Califf RM, Jennings LK, Kitt MM, Lorenz TJ. Clinical pharmacology of higher dose eptifibatide in percutaneous coronary intervention (the PRIDE study) Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:1097–102. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasuda T, Gold HK, Fallon JT, Leinbach RC, Guerrero JL, Scudder LE, Kanke M, Shealy D, Ross MJ, Collen D, et al. Monoclonal antibody against the platelet glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa receptor prevents coronary artery reocclusion after reperfusion with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in dogs. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1988;81:1284–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI113446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw GJ, Meunier JM, Lindsell CJ, Holland CK. Tissue plasminogen activator concentration dependence of 120 kHz ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2008;34:1783–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meunier JM, Holland CK, Lindsell CJ, Shaw GJ. Duty cycle dependence of 120 kHz ultrasound enhanced thrombolysis in human clot. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2007;33:576–783. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meunier JM, Smith DAB, Holland CK, Huang S, McPherson DD, Shaw GJ. 120 kHz pulsed ultrasound enhanced thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator-loaded echogenic liposomes. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2007b;122:3052. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanswell P, Seifried E, Su PC, Feuerer W, Rijken DC. Pharmacokinetics and systemic effects of tissue-type plasminogen activator in normal subjects. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 1989;46:155–62. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1989.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jambhekar SS, Breen PJ. Basic Pharmacokinetics. Pharmaceutical Press; London, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoenwald RD. Pharmacokinetic Principles of Dosing Adjustments: Understanding the Basics. Technomic Publishing Company, Inc.; Lancaster, PA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen A. Pharmacokinetics of the Recombinant Thrombolytic Agents: What is the Clinical Significance of Their Different Pharmacokinetic Parameters? BioDrugs. 1999;11:115–23. doi: 10.2165/00063030-199911020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gretler DD. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of eptifabatide in healthy subjects receiving unfractionated heparin or the low-molecular-weight heparin enoxaparin. Clinical therapeutics. 2003;25:2564–74. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gretler DD, Guerciolini R, Williams PJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of eptifibatide in subjects with normal or impaired renal function. Clinical therapeutics. 2004;26:390–8. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alton KB, Kosoglou T, Baker S, Affrime MB, Cayen MN, Patrick JE. Disposition of 14C-eptifibatide after intravenous administration to healthy men. Clinical therapeutics. 1998;20:307–23. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohman EM, Kleiman NS, Gacioch G, Worley SJ, Navetta FI, Talley JD, Anderson HV, Ellis SG, Cohen MD, Spriggs D, Miller M, Kereiakes D, Yakubov S, Kitt MM, Sigmon KN, Califf RM, Krucoff MW, Topol EJ. Combined accelerated tissue-plasminogen activator and platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa integrin receptor blockade with Integrilin in acute myocardial infarction. Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. IMPACT-AMI Investigators. Circulation. 1997;95:846–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collet JP, Montalescot G, Lesty C, Weisel JW. A structural and dynamic investigation of the facilitating effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in dissolving platelet-rich clots. Circ Res. 2002;90:428–34. doi: 10.1161/hh0402.105095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atar S, Luo H, Birnbaum Y, Nagai T, Siegel RJ. Augmentation of in-vitro clot dissolution by low frequency high-intensity ultrasound combined with antiplatelet and antithrombotic drugs. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2001;11:223–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1011912920777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robbie LA, Bennett B, Croll AM, Brown PA, Booth NA. Proteins of the fibrinolytic system in human thrombi. Thromb Haemost. 1996;75:127–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menon V, Harrington RA, Hochman JS, Cannon CP, Goodman SD, Wilcox RG, Schunemann HJ, Ohman EM. Chest; Thrombolysis and adjunctive therapy in acute myocardial infarction: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy; 2004; pp. 549S–75S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]