Abstract

Objective

This study contrasts the prevalence of successful aging in older adults with schizophrenia with their age peers in the community, and examines variables associated with successful aging in the schizophrenia group.

Methods

The schizophrenia group consisted of 198 community-dwelling persons aged ≥55 years who developed schizophrenia before age 45. A community comparison group (N = 113) was recruited using randomly selected block-groups. The three objective criteria proposed by Rowe and Kahn were operationalized using a 6-item summed score. The association of 16 predictor variables with the successful aging score in the schizophrenia group was examined.

Results

The community group had significantly higher successful aging scores than the schizophrenia group (4.3 vs. 3.0; t =8.36, df =309, p< .001). Nineteen percent of the community group met all 6 criteria on the Successful Aging Score versus 2% of the schizophrenia group. In regression analysis, only two variables –fewer negative symptoms and a higher quality of life index—were associated with the successful aging score within the schizophrenia group.

Conclusion

Older adults with schizophrenia rarely achieve successful aging, and do so much less commonly than their age peers. Only two significant variables were associated with successful aging, neither of which are easily remediable. The elements that comprise the components of successful aging, especially physical health, may be better targets for intervention.

Keywords: successful aging, social integration, schizophrenia

Psychology and medicine have increasingly broadened their interests from disability and disease to positive health and well-being (1, 2). The latter, in later life, is sometimes termed “successful aging,” and it is viewed as a state involving the absence of disability accompanied by high physical, cognitive, and social functioning (3–5). Successful aging is an ideal that all older persons might achieve under optimal circumstances. For persons with severe mental illness, the ideal life trajectory can be viewed as a process moving from diminishing psychopathology and impaired functioning to normalization to positive health and well-being. To our knowledge, there is no literature specifically examining factors that affect the prospects of successful aging among older adults with schizophrenia. The anticipated doubling of the older population with schizophrenia over the next two decades (6) makes the study of successful aging especially compelling. While successful aging focuses on personal attributes, it also suggests possibilities for altering societal conditions to amplify the possibilities for success.

There is no consensual definition of successful aging (5, 7–9). There are more than 29 different definitions that can be divided into objective and subjective factors (5, 8, 10). The most commonly cited objective factors are disability/physical functioning, cognition, social/productive engagement, longevity, environmental/finances, and mastery/growth. Subjective factors comprising successful aging have included life satisfaction/well being, self-rated health, self-rated successful aging, personality, and perceived control. Rowe and Kahn (3, 4) have posited the most widely used framework for examining objective successful aging. Their model includes absence of disease, disability, and risk factors, maintaining physical and mental functioning and active engagement with life. Depp and Jeste (5) found a mean of 20% successful agers among studies that included the components of Rowe and Kahn framework, with a range of 0.4 to 50 percent. In this study, we use a measure of objective successful aging based on Rowe and Kahn’s framework.

In the general population, successful aging has been associated with many factors (5, 8, 11–13). Depp and Jeste’s (5) review of the literature identified strong predictors of successful aging such as younger age, absence of arthritis, absence of hearing problems, better activities of daily living, and not smoking. Moderate predictors included higher exercise/physical activity level, better self rated health, lower systolic blood pressure, fewer medical conditions, better global cognitive function, and absence of depression. Limited correlations were seen between successful aging and higher income, greater education, currently married, and white ethnicity. Because of differences in definitions of successful aging, several of the predictor variables were sometimes considered as part of the construct rather than as an independent predictor variable.

With respect to persons with schizophrenia, Yanos and Moos’ (14) outcome research on functioning and human development is most relevant to our study. They have identified a variety of personal and environmental factors that may affect outcome in later life in schizophrenia that have not been typically included in studies of the general older population. These factors include psychiatric symptoms, traumatic life events, coping strategies, and features of treatment and residential programs.

This study has two aims:

To examine the rates of successful aging among older community dwelling persons with schizophrenia versus their age peers in the general community.

Using personal and psychosocial variables identified in prior studies of older persons with and without schizophrenia, we examine whether any of these variables are associated with successful aging in older adults with schizophrenia.

Methods

We recruited a community comparison group using Wessex Census STF3 files for Kings County (Brooklyn, N.Y.). We used randomly selected block groups as the primary sampling unit. An effort was made to interview all persons aged 55 and over in a selected block group by knocking on doors. Subjects from the selected block group were also recruited at senior centers, churches, and through personal references. We excluded persons with histories of treatment for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Subjects were offered $75 for completing the 2½-hour interview that consisted of demographic, biographical, clinical, and psychosocial instruments that have been described elsewhere(15, 16). The rejection rate was 7% in the schizophrenia group and 48 % of those contacted in the community group. We obtained written informed consent on all subjects.

Details of the methods have been reported elsewhere (15, 16). Briefly, we recruited subjects using persons aged 55 and over living in the community who developed early onset schizophrenia before the age of 45; this age cut-off accounts for about 85% of persons who develop schizophrenia (17). We used a stratified sampling method in which we attempted to interview approximately half the subjects from outpatient clinics and day programs and the other half from supported community residences. The latter included sites with varying degrees of on-site supervision. Inclusion was based on a DSM IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder that was conducted by clinical agency staff and by a lifetime illness review adapted from Jeste and associates (18). Persons with cognitive impairment too severe to complete the questionnaire were excluded from the study, i.e., defined as scores of <5 on the Mental Status Questionnaire (19).

Measures

Based on the literature review described above for older adults in the general population and the variables suggested by Yanos and Moos for persons with schizophrenia (14), we identified 16 predictor variables that we categorized into 3 variable sets: socio-demographic, psychosocial and environmental variables. There were 5, 6 and 5 variables in each of these variable sets, respectively (see Table 2). We excluded some putatively significant predictor variables that overlapped with the dependent variable. The following instruments were used to derive the independent and dependent variables: (a) Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale--CES-D(20), which was dichotomized into depressed and not depressed on the basis of a score of ≥ 8 which indicates depression with possible scores ranging from 0 to 80 (most depressed); (b) Positive and Negative Symptom Scale(PANSS)(21), from which we used the seven items each assessing positive and negative symptoms with each scale ranging from 1 to 7 (most severe); (c) the Financial Strain Scale (22) with possible scores ranging from 0 to 12 (least strain); (d) Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (23) with possible scores ranging from 0 to 42 (highest levels of dyskinesia); (e) the Quality of Life Index(24), a measure of self-perceived quality of life (satisfaction and importance) based on 33 items with possible scores ranging from 0 to 30; (f) the Dementia Rating Scale (25), that consists of subscales for attention, initiation and perseveration, construction, conceptualization, and memory, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 144 (higher cognitive functioning); (g) the Multilevel Assessment Inventory and the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale (26) from which we derived a summed score of the number of physical illnesses, the 7-item Basic Activities of Daily living Scale (BADL), and the 9-item Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL) (lower scores indicate more impairment); (h) the Cognitive Coping Scale, a 7-item with possible scores ranging from 0 to 7 derived from coping items proposed by by Pearlin and coauthors (27); (i) Lifetime Trauma and Victimization Scale (28), a 12-item scale based on the number of times persons experienced trauma or victimization such as crime victim, assault, physical or sexual abuse, incarceration with possible scores ranging from 0 to 36 (highest frequency); (j) the 4 item CAGE for alcoholism (29); (k) the Network Analysis Profile (30) that was used to derive two variables: the proportion of contacts providing sustenance assistance (e.g., money, food, help with health care) and proportion of persons who could be relied on; (l) the 6-item subjective successful aging score(31) with possible scores ranging from 0 to 6 (subjectively most satisfied); (k) the mean of the sum of the frequency of 5 mental health services (psychiatrist for medication, group treatment, individual psychotherapy or behavioral therapy, day program, family therapy) divided into those in the upper tercile (coded 1) versus those in the lower two terciles (coded 0).

Table 2.

Pearson’s Correlation Between Successful Aging Score and Predictor Variables.

| Mean(SD)/percent | N | Correlation (r) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 61.5(5.7) | 195 | −0.10 | 0.18 |

| Female (%) | 49 | 198 | −0.12 | 0.08 |

| Black (%) | 35 | 198 | 0.04 | 0.62 |

| Education | 12.8(8.7) | 192 | 0.03 | 0.72 |

| Personal income | 2.8(1.3) | 198 | 0.05 | 0.46 |

| Psychosocial Factors | ||||

| PANSS positive | 12.6(6.3) | 196 | −0.26 | 0.00 |

| PANSS negative | 12.0(6.0) | 197 | −0.37 | 0.00 |

| CAGE: any item lifetime | 33 | 198 | −0.00 | 0.97 |

| CESD ≥16 | 32 | 198 | −0.09 | 0.17 |

| Coping cognition | 5.6(1.8) | 195 | 0.24 | 0.00 |

| Lifetime trauma events | 3.5(3.8) | 197 | 0.07 | 0.36 |

| Environmental Factors | ||||

| Quality of Life Index | 21.7(5.3) | 195 | 0.22 | 0.00 |

| Supported residence (%) | 61 | 198 | −0.26 | 0.00 |

| Number of entitlements | 3.5(1.3) | 198 | 0.06 | 0.40 |

| Mental health services (upper tercile) | 33 | 198 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| Frequency medical services | .10 (.10) | 198 | 0.09 | 0.21 |

Note: CESD=Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; PANSS=Positive and Negative Symptom Scale

Income categories: 2= $4000–$6999; 3= $7000–$12,999;

Frequency of medical services: 0.25=monthly; 0.06= quarterly.

Using an adaptation of the operational criteria suggested by Strawbridge and colleagues (10) of Rowe and Kahn’s framework and the summed score approach of Bowling and Iliffe (32), we created a measure of successful aging that consisted of the summed score (range 0 to 6) of 3 domains comprising 6 indices: Avoiding disease & disability: (a) absence of cancer heart, lung, diabetic disease, symptoms of stroke, no smoking, Body Mass Index < 30, no untreated hypertension (b) No disabilities in Basic Activities of Daily Living; High cognitive & physical function: (a) Dementia Rating Scale ≥130(maximum 144) (b), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living ≥ 25 of maximum score of 28; Engagement with Life: (a) ≥3 confidants (b) ≥3 instrumental (i.e., helps or gives advice to others) linkages and/or working and/or does heavy and light housework.

We assessed the concurrent validity of the Successful Aging Score using 9 variables that corresponded to components of successful aging identified by Depp and Jeste (5) in the literature: total activities of daily living, dementia rating scale, quality of life index, total number of reliable contacts, number of physical illnesses, self-health rating, financial strain, greater perceived control over one’s life, and the subjective successful aging score. For the combined sample of community comparison and schizophrenia groups, successful aging correlated significantly (p<.001) with all 9 relevant variables, with correlations ranging from .22 to .65.

The internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) scores of all scales attained acceptable levels, i.e., ≥ .60 (33). The intra-class correlations (ICC) of the raters ranged from 0.79 to 0.99 on the various scales.

Data Analysis

We compared the mean values of schizophrenia and the community groups using a t-test. The unequal variance t-test was used when findings of the Levine test were significant. A chi-square test was used to examine the categorical variables. In looking at predictors of successful aging within the schizophrenia group, we initially used Pearson correlations, followed by a hierarchical regression analysis, with the variable sets of the integrative model entered in the following order: socio-demographics, psychosocial, and environmental. The dependent variable was normally distributed and there was no evidence of co linearity among the predictor variables, i.e., the variance inflation factor (VIF) was<2.1 for all variables.

Results

The schizophrenia sample consisted of 198 persons. Among these, 39% were living independently in the community and 61% in supported community residences. From the original community sample (n=206) we selected 113 persons who more closely matched the schizophrenia sample for age, gender, race, and income. Forty-nine percent of the schizophrenia group were women versus forty-nine percent of the community comparison group (x2 =0.00, df =1, p=0.96). The racial distribution was African American(35%), Caucasian (57%), Latino(7%), and Other (2%) in the schizophrenia group versus African American(36%), Caucasian (60%), Latino (2%), and Other (2%) in the community group (x2=3.62, df=3, p=.31). The mean ages of the schizophrenia and community comparison groups were 61.5 and 63.0 years (t =2.37, df =306, p=0.02), respectively. Thus, despite a small absolute difference in age between the two groups, this difference attained statistical significance. Median income for both groups fell within the same category ($7000–$12,999).

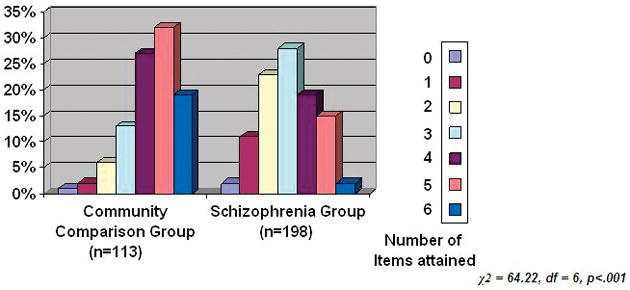

As compared to the community comparison group, the schizophrenia group had significantly lower mean total scores on the 6-item successful aging score (4.3± 1.3 vs. 3.0±1.4; t=8.36, df =309, p<.001). Nineteen percent of the community group met all six criteria on the successful aging score versus 2% of the schizophrenia group, and there were significant differences in the score distribution of the two groups (Figure 1). When contrasted with the community group, the schizophrenia group was significantly less likely to attain the success criterion on 5 of 6 component items of the successful aging score, with the BADL being the only item in which there were no group differences (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of Number of Items Attained on the Successful Aging Score

Table 1.

Comparison of Community Comparison and Schizophrenia Groups on Items Comprising Successful Aging

| Community Comparison Group (n=113) (%) | Schizophrenia Group(n=198) (%) | χ2 | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absence of severe physical illness | 43 | 15 | 29.91 | 1 | <.001 |

| Able to do basic daily activities (BADL) | 71 | 65 | 0.83 | 1 | <.362 |

| Able to do Instrumental daily activities (IADL) | 61 | 37 | 16.25 | 1 | <.001 |

| High cognitive functioning (Dementia rating scale) | 90 | 58 | 35.33 | 1 | <.001 |

| Social engagement (intimate contacts) | 77 | 52 | 18.87 | 1 | <.001 |

| Productivity | 94 | 80 | 10.84 | 1 | <.001 |

We separately examined the predictors of successful aging in the schizophrenia group. In bivariate analysis, 6 out of the 16 variables in our analyses were significantly correlated with successful aging (Table 2): independent living, higher use of cognitive coping strategies, lower PANSS positive and negative scores, greater use of mental health services, and higher quality of life index. In regression analysis (Table 3), only two variables retained significance: higher scores on the quality of life index and lower PANSS negative scores. The psychosocial variable set attained statistical significance, but the socio-demographic and environmental variable sets were not significant. The overall model accounted for 24.6% of the explained variance in successful aging, and it attained statistical significance.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis of Factors Predicting the Successful Aging Score

| Variable | β | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors | ||||

| Age | −0.13 | −1.71 | 179 | 0.09 |

| Female | −0.19 | −1.61 | 179 | 0.11 |

| Black | 0.03 | 0.47 | 179 | 0.64 |

| Education | 0.07 | 0.98 | 179 | 0.33 |

| Personal income | −0.07 | −0.91 | 179 | 0.36 |

| Psychosocial Factors | ||||

| PANSS positive | −0.12 | −1.25 | 179 | 0.21 |

| PANSS negative | −0.19 | −2.06 | 179 | 0.04 |

| CAGE: any item lifetime | −0.00 | −0.12 | 179 | 0.90 |

| CESD ≥16 | 0.04 | 0.52 | 179 | 0.60 |

| Coping cognition | 0.06 | 0.80 | 179 | 0.42 |

| Lifetime trauma events | 0.10 | 1.33 | 179 | 0.18 |

| Environmental Factors | ||||

| Quality of Life Index | 0.20 | 2.41 | 179 | 0.01 |

| Supported residence | −0.13 | −1.62 | 179 | 0.11 |

| Number of entitlements | −0.02 | −0.30 | 179 | 0.77 |

| Mental health services (upper tercile) | 0.05 | 0.67 | 179 | 0.50 |

| Frequency of medical services | −0.00 | −0.12 | 179 | 0.90 |

Note: Note: CESD=Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; PANSS=Positive and Negative Symptom Scale.

Sociodemographic variable set: F=1.27, df 5, 174, p=.28

Psychosocial variable set: F=5.21, df6, 168, p<.001

Environmental variable set: F=2.14, df5, 163, p=06

Overall model: F=3.16, df 16,163, p<.001; R2 =.246

Discussion

With respect to our first aim of contrasting successful aging among older community adults with older persons with schizophrenia, the community residents were about 10 times more likely to meet the criteria of successful aging, and the likelihood of the schizophrenia group attaining successful aging was remote (1 in 50). This contrasts sharply with other outcomes in the recovery continuum in which we found that nearly half attained clinical remission and one-sixth attained “objective recovery” (operationalized as clinical plus functional remission) (31).

We believe that our measure of successful aging is a valid one. First, our finding for the community comparison group was consistent with those in other older populations, thereby supporting the validity of our measure. We found that 19% of our community comparison group met successful aging, which was similar to the mean of 20% in various successful aging studies that included both cognitive and disability/physical function (5, 11). Moreover, Strawbridge and associates (11), using criteria that were nearly identical to ours, found a successful aging rate of 25% among subjects who were aged 65 to 69. Second, we found that our measure correlated significantly with nine other components of successful aging that had been cited in Depp and Jeste’s (5) review of the literature.

With respect to our second aim of identifying those variables associated with successful aging among older persons with schizophrenia, when all the variables were examined in concert, we found that only the quality of life index and negative symptoms attained significance. Moreover, only one of the three variable sets attained significance, and the 16 variables combined could not explain three fourths of the variance in successful aging. Differences from earlier research may reflect our use of a multivariate analysis with 16 independent variables, our construct of successful aging, or the nature of our sample, i.e., persons with schizophrenia.

With respect to the significant variables in the analyses, it was not surprising that negative symptoms were associated with successful aging since they have been linked with several items comprising the successful aging measure such as cognitive deficits and diminished social interaction (34–35). The association between quality of life and successful aging is consistent with a majority of earlier findings in the general population (13, 14). Our cross-sectional data cannot determine causal direction, although it seems plausible that having more objective components of successful aging would engender more positive feelings regarding life quality.

Finally, the recovery ethos in schizophrenia affirms the centrality of the consumer perspective. Our focus on an objective measure of successful aging raises the question as to whether we are vitiating the importance of the subjective view. In studies of the general population, older persons’ subjective response to whether they were aging successfully was considerably greater than the levels found using objective criteria (11, 14). Although it is important to be responsive to self-assessments of outcome, several writers have cautioned that the correlations between objective factors and perceived measures may be attenuated by the lower expectations of persons with schizophrenia (15, 36).

This study has several strengths. It is the first study to examine the prevalence and associated factors for successful aging among older persons with schizophrenia. It uses a large multiracial sample of older adults with schizophrenia living in a variety of community settings, albeit a convenience sample, and a well-matched comparison group. Our measure of successful aging met various initial criteria for validity, e.g., concurrent validity and levels in the general population that were similar to earlier studies. However, the study is limited by the fact that it is cross-sectional, and consequently, we are unable to determine the stability of our outcome measures over time. Future studies must employ longitudinal assessments. Second, the data are restricted to one urban area in the Northeast, so its generalizability must be determined, although several of our findings resembled those found previously. Third, our measure of successful aging will likewise need further validation with other samples before its utility can be assured. Fourth, the sample consists of persons recruited from outpatient programs and supported residences, and consequently, we did not include persons who are no longer in treatment or living in institutions. The literature suggests that approximately 10 to 15 percent of persons may no longer be in treatment (37–39), but these numbers are at least balanced by the 15 percent of persons in nursing homes or hospitals (40), as well as those who have dropped out of treatment and are functioning poorly. However, it is possible that persons no longer in treatment might attain levels equivalent to elders in the general community. Consequently, rates of successful aging may be even higher among the entire older population with schizophrenia than found here. Lastly, because we used multiple comparisons in our analyses, there is an increased possibility of type 1 errors. However, because this is an exploratory study, we wished to avoid type 2 errors, especially in the interpretation of the regression analysis.

In summary, not surprisingly, our data indicated that for older adults with schizophrenia, the prospects to attain successful aging are remote, and that it occurs much less commonly than among their age peers. Moreover, we were only able to identify two significant variables (higher perceived quality of life, absence of negative symptoms) associated with successful aging, neither of which are easily remediable. On the other hand, if persons with schizophrenia averaged one component higher on the summed successful aging measure, they would have attained levels approaching those of their community age peers. More to the point, if persons with schizophrenia attained the physical health status of their community peers (see Table 1), about 7% of the group would meet criteria for successful aging. Although concepts such as recovery in schizophrenia have included “functional recovery” (41), clinicians have not fully recognized the importance of physical health as a critical element. This is beginning to change. Interventions are needed at the individual level (e.g., lifestyle improvements), but also at the systems level, where it entails developing innovative and age appropriate programs to address health care delivery and physical rehabilitation needs throughout the lifespan.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants SO6-GM-74923 and SO6-GM-5465.

The authors thank Joseph Eimicke, B.A., Jeanne Teresi, Ph.D., Robert Yaffee, Ph.D., Michelle Kehn, M.A., Richa Pathak, M.D., and Community Research Applications for their assistance.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Ryff CD, Singer BH, Love GD. Positive health: connecting well-being with biology. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 2004;359:1383–94. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seligman MP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive Psychology Progress: Emperical validation of Interventions. American psychologist. 2005;60:410–21. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Human Aging: usual and successful. Science. 1987;237:143–149. doi: 10.1126/science.3299702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997;37:433–440. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and Predictors of Successful Aging: A Comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen CI, Vahia I, Reyes P, et al. Schizophrenia in later life: clinical symptoms and social well-being. Psychiatric services. 2008;59:232–234. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouwenhand C, Denise TD, Bensing JM. A review of successful aging models: Proposing proactive coping as an important additional strategy. Clinical psychology Reviw. 2007;27:873–884. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phelan EA, Larson EB. ‘Successful aging’—where next? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1306–1308. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.t01-1-50324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lupien SJ, Wan N. Successful ageing: from cell to self. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1413–1426. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI, Cohen RD. Successful aging and well-being: self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist. 2002;42:727–733. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peel NM, McClure RJ, Barlett HP. Behavioral determinants of healthy aging. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livingston G, Cooper C, Woods J, et al. Successful ageing in adversity: the LASER-AD longitudinal study. J neurol psychiatry. 2008;79:641–645. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.126706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montross LP, Depp C, Daly J, et al. Correlates of self rated Successful aging among community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:43–51. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192489.43179.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanos PT, Moos RH. Determinants of functioning and well being among individuals with schizophrenia: An integrated model. Clinical Psychology review. 2007;27:58–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bankole AO, Cohen CI, Vahia I, et al. Factors Affecting Quality of Life in a Multiracial Sample of Older Persons with Schizophrenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:1015 – 1023. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31805d8572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diwan S, Cohen CI, Bankole AO, et al. Depression in older adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Prevalence and associated factors. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:991 – 998. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31815ae34b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris AE, Jeste DV. Late-onset schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14:39–55. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeste DV, Symonds LL, Harris MJ, et al. Non-dementia non-praecox dementia praecox? Late-onset schizophrenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5:302–317. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199700540-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn RL, Goldfarb AI, Pollack M, et al. Brief objective measures for the determination of mental status in the aged. Am J Psychiatry. 1960;117:326–328. doi: 10.1176/ajp.117.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The centre for Epidemiology studies depression scale. A self report depression for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;3:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearlin LJ, Mehaghan EG. The stress process. J health Soc Behav. 1981;22:37–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute of Mental Health. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Intercom. 1975;4:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrans CE, Power MJ. Quality of Life Index: development and psychometric properties. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1985;8:15–24. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coblentz JM, Mattis S, Zingesser LH, et al. Presenile dementia: clinical aspects and evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. Archives of Neurology. 1973;29:299–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1973.00490290039003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawton MP, Moss M, Fulcomer M, et al. A research and service-oriented multilevel assessment instrument. Gerontology. 1982;37:91–99. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health & Soc Behav. 1978;18:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen CI, Ramirez M, Teresi J, et al. Predictors of becoming redomiciled among older homeless women. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:67–74. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ewing JA. Detecting Alcoholism: The CAGE Questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sokolovsky J, Cohen CI. Toward a resolution of methodological dilemmas in network mapping. Schizophr Bull. 1981;7:109–116. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen CI, Pathak R, Ramirez, et al. Outcome Among Community Dwelling Older Adults with Schizophrenia: Results Using Five Conceptual Models. Community Ment Health J. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9161-8. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowling H, Iliffe S. which model of successful ageing should be used? Baseline findings from a British longitudinal survey of ageing. Age and Ageing. 2006;35:607–614. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunally JC. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvey PD, Lombardi J, Leibman M, et al. Cognitive impairment and negative symptoms in geriatric chronic schizophrenic patients:a follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research. 1996;22:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamilton NG, Ponzoha CA, Cutler DL, et al. Social networks and negative versus positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1989;15:625–633. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katschnig H. schizophrenia and quality of life. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:33–37. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harding CM. In: Changes in schizophrenia across time: paradoxes, patterns and predictors, in schizophrenia into later life: treatment, research and policy. Cohen CI, editor. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2003. pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Auslander LA, Jeste DV. Sustained remission among of schizophrenia among community-dwelling older out patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1490–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ciompi L. The natural history of schizophrenia in the long term. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:413–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McAlpine DD. In: Patterns of care for persons 65 years and older with schizophrenia, in schizophrenia into later life: treatment, research and policy. Cohen CI, editor. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2003. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diamond RJ, Scheifler PL, editors. Improving the therapist, prescriber, client relationship. New York: W. W. Norton & co; 2007. Treatment collaboration. [Google Scholar]