Abstract

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is characterized by a disability to produce reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) caused by a defect of phagocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase. A hyperinflammatory response to immune activation has been reported to contribute to the pathology of CGD. The tryptophan catabolizing enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is considered critical for regulating immune responses and suppression of inflammation. IDO is generally believed to require ROI for enzymatic activity and was found to be inactive in murine CGD. Here, we report that, strikingly, in human CGD IDO metabolic activity is intact. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells generated from CGD patients, harbouring X-linked and autosomal recessive forms of CGD, and from healthy controls produced similar amounts of the tryptophan metabolite kynurenine upon activation with lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ. Thus, in humans, ROI apparently are dispensable for IDO activity. Hyperinflammation in human CGD cannot be attributed to disabled IDO activation.

Keywords: Chronic granulomatous disease; Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Tryptophan catabolism; Reactive oxygen intermediates; Hyperinflammation

Introduction

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is an inherited immunodeficiency characterized by recurrent severe bacterial and fungal infections. The underlying genetic defect of the phagocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase results in failure to produce reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI), favoring invasive infections [1]. CGD is also characterized by a hyperinflammatory response following immune activation [2,3], which might lead to granuloma formation even in the absence of pathogen [4]. A recent report proposed that impaired activation of the immunoregulatory indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) pathway [5–7] contributed to an amplified inflammatory response in murine CGD [8]. IDO, mediating tryptophan metabolism, is a heme-containing enzyme and requires posttranslational activation through the reduction of the ferric (Fe3+) to the ferrous (Fe2+) form [9] before the metabolic breakdown of tryptophan along the kynurenine pathway can be initiated. Previous studies proposed an essential role for superoxide and ROI for IDO activation [10,11]. In consistence with this concept, IDO activity was found to be abolished in CGD mice [8]. CGD (p47 phox−/−) (phox, phagocytic oxidase) mice responded to experimental Aspergillus infection with hyperinflammation, indicated by severe lung injury and a Th17 polarized response, and showed reversal of the hyperinflammatory phenotype upon application of the tryptophan breakdown product kynurenine.

As this finding may have significant impact on the understanding of CGD pathophysiology, we investigated whether defective IDO activation was also present in human CGD.

Methods

Heparinized blood was collected after written informed consent from four CGD patients, including one with X-linked (gp91phox) and three with autosomal recessive (p47phox) inheritance (Table 1). All patients were free of infection and presented no clinical or laboratory signs of inflammation at the time of blood collection (not shown). The first diagnosis of CGD was made in all patients by < 10% oxygen radical production, as determined by chemiluminescence, dihydrorhodamine, and/or nitroblue tetrazolium tests in PMA-stimulated phagocytes, followed by genetic analyses. Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of the St. Anna Children's Hospital, Vienna, Austria. All patients and/or their parents gave written informed consent.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient no. | Sex/age | Age at diagnosis | Diagnosis |

Clinical course | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional | Genotype | |||||

| 1 | M, 5 years | 2 years | CL < 1% | p91phox | Clinically well | Prophylactic TMP, Itra |

| 2a | M, 11 years | 11 years | DHR 0% | p47phox | Recurrent blepharitis, recurrent skin abscesses, clinically well at blood collection | Prophylactic TMP, Itra |

| NBT 0% | ||||||

| 3a | F, 8 years | 8 years | DHR 11% | p47phox | Recurrent diarrhea, recurrent oral ulcers, lymphadenitis, clinically well at blood collection | Prophylactic TMP, Itra |

| NBT 0% | ||||||

| 4 | F, 12 years | 6 years | DHR 0% | p47phox | Multifocal pleuropneumonia (Burkholderia multivorans) at age 6 years, clinically well at blood collection | None (non-compliant) |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; CL, chemiluminescence; DHR, dihydrorhodamine; NBT, nitroblue tetrazolium; TMP, trimethoprim; Itra, itraconazole.

Siblings.

Immature dendritic cells (DCs) were generated from CGD patients and controls in parallel, as described [12], and were activated with 50 ng lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Calbiochem; Escherichia coli O111:B4) and 1000 U/ml interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) (Boehringer Ingelheim) for 48 hours. Following stimulation, the DC recovery rate was analyzed by flow cytometry using propidium-iodide staining. IDO protein expression was determined by immunoblotting, using a monoclonal mouse anti-human IDO antibody kindly provided by O. Takikawa (National Institute for Longevity Sciences, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Aichi, Japan) [12]. IDO activity was determined measuring the release of the tryptophan breakdown product kynurenine into cell culture supernatants by high performance liquid chromatography [12]. The kynurenine release by patient cells was compared to that of control cells by calculating the mean kynurenine concentration ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) in cell culture supernatants. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student's t-test (paired, two-tailed). A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results and discussion

To analyze whether the IDO immunoregulatory pathway was impaired in human CGD, we compared the ability of IDO activation in monocyte-derived DCs obtained from CGD patients and from healthy controls. We activated immature DCs with LPS and IFN-γ for 48 hours. This strategy recapitulates to some extent inflammatory stimulation and consistently results in abundant IDO activity in human cells [12].

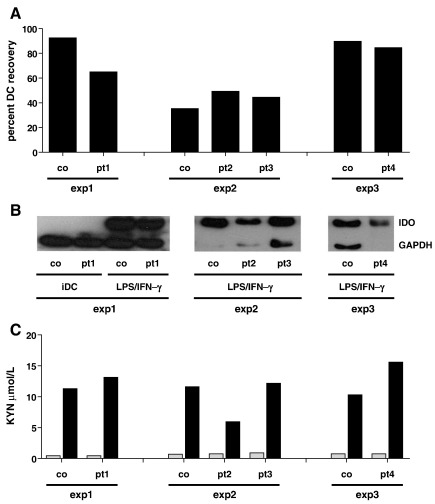

To exclude that any difference in IDO activity in CGD patients and controls was related to an altered sensitivity to apoptosis in CGD patients, we first ascertained that the recovery rate of CGD and control DCs after activation with LPS/IFN-γ was within the same range (Fig. 1A). Likewise, upon activation, patient and control DCs developed a similarly mature phenotype, as assessed by flow cytometric staining for expression of CD83, CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR [12] (not shown). Next, immunoblotting of IDO protein expression showed that LPS/IFN-γ activation of immature DCs induced comparable IDO protein expression in CGD and in control DCs (Fig. 1B). Strikingly, analyzing IDO activity, we found that abundant tryptophan catabolism was consistently inducible in DCs of CGD patients. While immature DCs did not metabolize tryptophan (Fig. 1C) [12], activation of DCs obtained from CGD patients resulted in the release of 11.7 ± 4.1 µM kynurenine, and this was within the same range as that of control cells, which released 11.2 ± 0.6 µM kynurenine (p = 0.83) (Fig. 1C). These findings clearly demonstrate that in humans the induction of IDO enzymatic activity is not essentially dependent of ROI and that the IDO activity in CGD patients is preserved.

Figure 1.

Normal expression and activation of IDO in DCs of human CGD patients. (A) Recovery rate of DCs after activation with LPS/IFN-γ for 48 hours as healthy control derived DCs. (B) IDO immunoblotting; note that immunoblotting of immature DCs (iDC) was not possible due to low cell numbers obtained from patients 2–4. (C) kynurenine release into cell culture supernatants; gray bars, immature DCs; black bars, DCs activated with LPS/IFN-γ for 48 hours. co, control; pt, patient; KYN, kynurenine.

In accordance with our findings and contrasting the previous concept of IDO activation being dependent on superoxide and ROI [10], a recent study reported that in human cells superoxide dismutase mimetics, while being able to decrease intracellular superoxide, failed to significantly alter IDO activity. Instead, cytochrome b5, in the presence of cytochrome P450 reductase and NADPH, was found to be sufficient for reduction of Fe3+-IDO to Fe2+-IDO, thus allowing for effective initiation of IDO-mediated tryptophan breakdown [13], indicating that cytochrome b5 rather than superoxide plays a major role in the activation of IDO in human cells.

Yet, other ROI-dependent processes such as activation of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which serves as an antioxidant response element and restrains the activation of NF-κB [14], might contribute to the hyperinflammatory state in some patients with CGD [15].

In conclusion, this study provides clear evidence that the IDO immunoregulatory pathway is intact in human CGD despite defective NADPH oxidase function. Our findings are consistent with the observation of normal kynurenine levels in the sera of a CGD patient, who suffered from severe Aspergillus infection, before as well as after gene therapy when the patient was cured from this infection [16]. The hyperinflammatory state in some CGD patients may be linked to an impaired immunoregulatory activity of ROI, e.g., by insufficient Nrf2 activation, or other mechanisms still to be discovered. Should kynurenine be considered as a treatment option in CGD at all the rationale for its use could be to augment rather than to replace IDO-mediated immunoregulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for their trust. This work was supported by a grant of the Chronic Granulomatous Disorder Research Trust, United Kingdom (J.R.) and the Austrian Science Foundation (project # 20865 to A.H.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors thank Marion Zavadil for her help in editing the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Birgit Jürgens, Email: birgit.juergens@ccri.at.

Dietmar Fuchs, Email: Dietmar.Fuchs@i-med.ac.at.

Janine Reichenbach, Email: Janine.Reichenbach@kispi.uzh.ch.

Andreas Heitger, Email: andreas.heitger@ccri.at.

References

- 1.Stasia M.J., Li X.J. Genetics and immunopathology of chronic granulomatous disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30:209–235. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bylund J., MacDonald K.L., Brown K.L., Mydel P., Collins L.V., Hancock R.E., Speert D.P. Enhanced inflammatory responses of chronic granulomatous disease leukocytes involve ROS-independent activation of NF-kappa B. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1087–1096. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.F.L. van de Veerdonk, S.P. Smeekens, L.A. Joosten, B.J. Kullberg, C.A. Dinarello, J.W. van der Meer, and M.G. Netea, Reactive oxygen species-independent activation of the IL-1beta inflammasome in cells from patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 3030-3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Marks D.J., Miyagi K., Rahman F.Z., Novelli M., Bloom S.L., Segal A.W. Inflammatory bowel disease in CGD reproduces the clinicopathological features of Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:117–124. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grohmann U., Fallarino F., Puccetti P. Tolerance, DCs and tryptophan: much ado about IDO. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:242–248. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellor A.L., Munn D.H. IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hainz U., Jurgens B., Heitger A. The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in transplantation. Transpl Int. 2007;20:118–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romani L., Fallarino F., De Luca A., Montagnoli C., D'Angelo C., Zelante T., Vacca C., Bistoni F., Fioretti M.C., Grohmann U., Segal B.H., Puccetti P. Defective tryptophan catabolism underlies inflammation in mouse chronic granulomatous disease. Nature. 2008;451:211–215. doi: 10.1038/nature06471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas S.R., Terentis A.C., Cai H., Takikawa O., Levina A., Lay P.A., Freewan M., Stocker R. Post-translational regulation of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity by nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23778–23787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirata F., Ohnishi T., Hayaishi O. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Characterization and properties of enzyme. O2-complex. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:4637–4642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sono M. The roles of superoxide anion and methylene blue in the reductive activation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by ascorbic acid or by xanthine oxidase-hypoxanthine. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1616–1622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jurgens B., Hainz U., Fuchs D., Felzmann T., Heitger A. Interferon-gamma-triggered indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase competence in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells induces regulatory activity in allogeneic T cells. Blood. 2009;114:3235–3243. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maghzal G.J., Thomas S.R., Hunt N.H., Stocker R. Cytochrome b5, not superoxide anion radical, is a major reductant of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12014–12025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thimmulappa R.K., Lee H., Rangasamy T., Reddy S.P., Yamamoto M., Kensler T.W., Biswal S. Nrf2 is a critical regulator of the innate immune response and survival during experimental sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:984–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI25790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.B.H. Segal, W. Han, J.J. Bushey, M. Joo, Z. Bhatti, J. Feminella, C.G. Dennis, R.R. Vethanayagam, F.E. Yull, M. Capitano, P.K. Wallace, H. Minderman, J.W. Christman, M.B. Sporn, J. Chan, D.C. Vinh, S.M. Holland, L.R. Romani, S.L. Gaffen, M.L. Freeman, and T.S. Blackwell, NADPH oxidase limits innate immune responses in the lungs in mice. PLoS One 5 e9631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Bianchi M., Hakkim A., Brinkmann V., Siler U., Seger R.A., Zychlinsky A., Reichenbach J. Restoration of NET formation by gene therapy in CGD controls aspergillosis. Blood. 2009;114:2619–2622. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]