Abstract

Pregnancy and the early years of the child’s life offer an opportune time to prevent a host of adverse maternal and child outcomes that are important in their own right, but that also have significant implications for the development of criminal behaviour. This paper summarizes a 30-year programme of research that has attempted to improve the health and development of mothers and infants and their future life prospects with prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses. The programme, known today as the Nurse-Family Partnership, is designed for low-income mothers who have had no previous live births. The home visiting nurses have three major goals: to improve the outcomes of pregnancy by helping women improve their prenatal health; to improve the child’s health and development by helping parents provide more sensitive and competent care of the child; and to improve parental life-course by helping parents plan future pregnancies, complete their educations, and find work. Given consistent effects on prenatal health behaviours, parental care of the child, child abuse and neglect, child health and development, maternal life-course, and criminal involvement of the mothers and children, the programme is now being offered for public investment throughout the United States, where careful attention is being given to ensuring that the programme is being conducted in accordance with the programme model tested in the randomized trials. The programme also is being adapted, developed, and tested in five countries outside of the US: the Netherlands, Germany, England, Australia, and Canada, where programmatic adjustments are being made to accommodate different populations served and health and human service contexts. We believe it is important to test this programme in randomized controlled trials in these new settings before it is offered for public investment.

Keywords: Crime, Development, Health, Home visiting, Nurses

Introduction

Pregnancy and the early years of children’s lives offer an opportune time to prevent a host of adverse maternal and child outcomes that are important in their own right, but that also have significant implications for the development and prevention of criminal behaviour. Over the past 30 years, our team of investigators has been involved in developing and testing a programme of prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses aimed at improving the health of mothers and children and their future life prospects. Known as the Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP), this programme is different from most mental-health, substance-abuse, and crime-prevention interventions tested to date in that it focuses on improving neuro-developmental, cognitive, and behavioural functioning of the child by improving prenatal health; reducing child abuse and neglect and neuro-developmental and behavioural dysregulation; and enhancing family functioning and economic self-sufficiency in the first two years of the child’s life. These early alterations in biology, behaviour, and family context are expected to shift the life-course trajectories of children living in highly disadvantaged families and neighbourhoods away from psychopathology, substance use disorders, and risky sexual behaviours (Olds 2007). The programme is designed to alter those influences early in life that contribute to early-onset conduct disorder (Moffitt 1993).

Noting that adolescent substance use disorders (SUDs) are associated with childhood psychopathology, Kendall and Kessler (2002) have recommended public investments in earlier treatment of childhood mental disorders, rather than preventive interventions, as a way of reducing the rates of psychopathology and SUDs. They question the value of preventive interventions on the grounds that many who need such interventions fail to participate because they have no sense of vulnerability to motivate participation. Women who qualify for the NFP (low-income pregnant women bearing first babies), however, have profound senses of vulnerability that increase their participation in the NFP (Olds 2002). Moreover, today the programme is being integrated into obstetric and paediatric primary care services in hundreds of communities throughout the United States with essential fidelity to the model tested in randomized controlled trials (Olds, Hill, O’Brien, et al. 2003). The NFP is thus a potentially important intervention to complement existing mental health prevention and treatment efforts, given its success in engaging vulnerable pregnant women and its impact on a wide range of much earlier risks for compromised adolescent mental health and behaviour. In evaluating this programme, it is important to understand its theoretical and empirical foundations.

Theory-driven

The NFP also is grounded in theories of human ecology (Bronfenbrenner 1979, 1995:619–647), self-efficacy (Bandura 1977), and human attachment (Bowlby 1969). Together, these theories emphasize the importance of families’ social context and individuals’ beliefs, motivations, emotions, and internal representations of their experience in explaining development. Human ecology theory, for example, emphasizes that children’s development is influenced by how their parents care for them, and that, in turn, is influenced by characteristics of their families, social networks, neighbourhoods, communities, and the interrelations among them (Bronfenbrenner 1979). Drawing from this theory, nurses attempt to enhance the material and social environment of the family by involving other family members, especially fathers, in the home visits, and by linking families with needed health and human services.

Parents help select and shape the settings in which they find themselves, however (Plomin 1986). Self-efficacy theory provides a useful framework for understanding how women make decisions about their health-related behaviours during pregnancy, their care of their children, and their own personal development. This theory suggests that individuals choose those behaviours that they believe 1) will lead to a given outcome, and 2) they themselves can successfully carry out (Bandura 1977). In other words, individuals’ perceptions of self-efficacy influence their choices and determine how much effort they put forth to get what they want in the face of obstacles.

The programme therefore is designed to help women understand what is known about the influence of their behaviours on their health and on the health and development of their babies. The home visitors help parents establish realistic goals and small achievable objectives that, once accomplished, increase parents’ reservoir of successful experiences. These successes, in turn, increase women’s confidence in taking on larger challenges.

Finally, the programme is based on attachment theory, which posits that infants are biologically predisposed to seek proximity to specific care-givers in times of stress, illness, or fatigue in order to promote survival (Bowlby 1969). Attachment theory hypothesizes that children’s trust in the world and their later capacity for empathy and responsiveness to their own children once they become parents is influenced by the degree to which they formed an attachment with a caring, responsive, and sensitive adult when they were growing up, which affects their internal representations of themselves and their relationships with others (Main et al. 1985).

The programme therefore explicitly promotes sensitive, responsive, and engaged care-giving in the early years of the child’s life (Dolezol and Butterfield 1994). To accomplish this, the nurses try to help mothers and other care-givers review their own child-rearing histories and make decisions about how they wish to care for their children in light of the way they were cared for as children. Finally, the visitors seek to develop an empathic and trusting relationship with the mother and other family members because experience in such a relationship is expected to help women eventually trust others and to promote more sensitive, empathic care of their children.

Epidemiologic foundations

Focus on low-income, unmarried, and teen parents

The NFP registers low-income women having first births, and thus enrols large numbers of unmarried and adolescent mothers. These populations have higher rates of the problems the programme was designed originally to address (e.g. poor birth outcomes, child abuse and neglect, and diminished parental economic self-sufficiency) (Elster and McAnarney 1980; Overpeck et al. 1998). Women bearing first children are particularly receptive to this service, and to the extent that they improve their prenatal health, care of their first-borns, and life-course they are likely to apply those skills to subsequent children they choose to have (Olds 2002, 2006).

Programme content

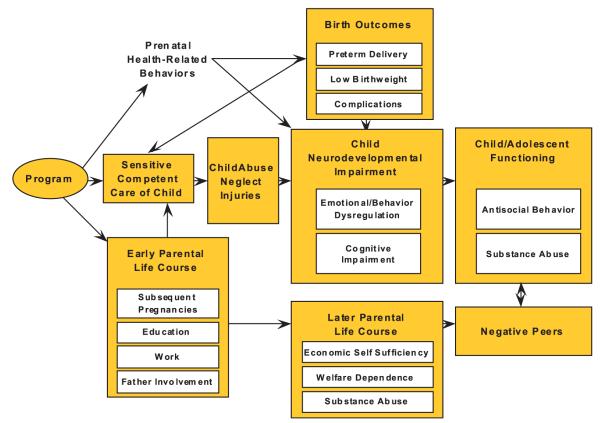

The NFP seeks to reduce specific risks and promote protective factors for poor birth outcomes, neuro-cognitive impairments, child abuse and neglect, injuries, and compromised parental life-course (Figure 1). These reduced exposures to prenatal toxicants, child abuse and neglect, and untoward family environments are expected to shift the child’s health and development toward greater behavioural regulation and interpersonal and cognitive competence, eventually leading to reduced exposure to and engagement with antisocial, deviant peers.

Figure 1. General conceptual model of programme influences on maternal and child health and development.

Source: With permission from Springer Science+Business Media: Olds, D.L. (2002). Prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses: from randomized trials to community replication. Prevention Science, 3(3), 153–72, Figure 1.

Prenatal health behaviours

Prenatal tobacco and alcohol exposure increases the risk for foetal growth restriction (Kramer 1987), preterm birth (Kramer 1987), and neuro-developmental impairment (e.g. attention-deficit disorder, cognitive and language delays) (Fried et al. 1987; Mayes 1994; Olds, Henderson, and Tatelbaum 1994a, 1994b; Streissguth et al. 1994:148–183; Milberger et al. 1996; Olds 1997; Sood et al. 2001). Children born with subtle neurological perturbations resulting from prenatal exposure to stress and substances are more likely to be irritable and inconsolable (Saxon 1978; Streissguth et al. 1994:148–183; Clark et al. 1996), making it more difficult for parents to enjoy their care. Improved prenatal health thus helps parents become competent care-givers.

Sensitive, competent care of the child

Parents who empathize with and respond sensitively to their infants’ cues are more likely to understand their children’s competencies, leading to less maltreatment and unintentional injuries (Peterson and Gable 1998:291–318; Cole et al. 2004, unpublished paper). Competent early parenting is associated with better child behavioural regulation, language, and cognition (Hart and Risley 1995). Later demanding, responsive, and positive parenting can provide some protection from the damaging effects of stressful environments and negative peers (Field et al. 1998; Bremner 1999) on externalizing symptoms and substance use (Baumrind 1987; Johnson and Pandina 1991; Cohen et al. 1994; Biglan et al. 1995; Field et al. 1998; Grant et al. 2000). In general, poor parenting is correlated with low child serotonin levels (Pine 2001, 2003) which, in turn, are implicated in stress-induced delays in neuro-development (Bremner and Vermetten 2004).

Early parental life-course

Closely spaced subsequent births undermine unmarried women’s educational achievement and work-force participation (Furstenberg et al. 1987), and limit their time to protect their children. Married couples are more likely to achieve economic self-sufficiency, and their children are at lower risk for a host of problems (McLanahan and Carlson 2002). Nurses therefore promote fathers’ involvement and help women make appropriate choices about the timing of subsequent pregnancies and the kinds of men they allow into their lives.

Modifiable risks for early-onset antisocial behaviour, substance-use disorders, and depression

Many of the prenatal and infancy risks addressed by this programme are risks for early-onset antisocial behaviour, depression, and substance use (Hawkins et al. 1992; Olds, Eckenrode et al. 1997; Greene 2001; Olds 2002; Clark and Cornelius 2004; Olds, Sadler, and Kitzman 2007). Children with early-onset conduct problems are more likely to have subtle neuro-developmental deficits (Streissguth et al. 1994:148–183; Milberger et al. 1996; Olds, Eckenrode et al. 1997; Arseneault et al. 2002) that may contribute to, be caused by, or be exacerbated by abusive and rejecting care early in life (Moffitt 1993; Raine et al. 1994). Aggressive and disinhibited behaviours that emerge prior to puberty are risks for adolescent SUD (Tarter et al. 2003; Clark et al. 2005), antisocial behaviour, and risky sexual behaviour, such as unprotected sex with multiple partners. Early-onset antisocial behaviour leads to more serious and violent offending that is different from normative acting out in mid-adolescence (Loeber 1982).

A similar configuration of risks is associated with early-onset major depressive disorder (MDD). Children who develop MDD in childhood, compared to those who develop MDD as adults, are more likely to have perinatal medical complications, motor skill deficits, behavioural and emotional problems (Jaffee et al. 2002), especially impulsivity, risky decision-making, and problems with verbal recognition memory and inattention (Aytaclar et al. 1999), as well as care-taker instability, criminality, and psychopathology in their family of origin.

Both conduct disorder and early substance use increase the risk for later SUDs and chronic antisocial behaviour (Boyle et al. 1992; Moffitt 1993; Raine et al. 1994; Clark et al. 1997; Lynskey et al. 2003; Clark and Cornelius 2004; Clark et al. 2005). Children who begin using cannabis in adolescence (<17 years) are at greater risk for developing SUDs (Lynskey et al. 2003). The reductions in prenatal risks, dysfunctional care of the infant, and improvements in family context are thus likely to have long-term effects on youth antisocial behaviour that has its roots in early experience.

Programme design

The same basic programme design has been used in Elmira, Memphis, and Denver.

Frequency of visitation

The recommended frequency of home visits changed with the stages of pregnancy and was adapted to parents’ needs, with nurses visiting more frequently in times of family crisis. Mothers were enrolled through the end of the second trimester of pregnancy. In Elmira, Memphis, and Denver, the nurses completed an average of 9 (range 0–16), 7 (range 0–18), and 6.5 (range 0–17) visits during pregnancy, respectively; and 23 (range 0–59), 26 (range 0–71), and 21 (range 0–71) visits from birth to the child’s second birthday. Paraprofessionals in Denver completed an average of 6 (range 0–21) prenatal visits and 16 (range 0–78) during infancy. Each visit lasted approximately 75–90 minutes.

Nurses as home visitors

Nurses were selected as home visitors in the Elmira and Memphis trials because of their formal training in women’s and children’s health and their competence in managing the complex clinical situations often presented by at-risk families. Nurses’ abilities to competently address mothers’ and family members’ concerns about the complications of pregnancy, labour, and delivery, and the physical health of the infant are thought to provide nurses with increased credibility and persuasive power in the eyes of family members. In the Denver trial, we compared the relative impact of the programme when delivered by nurses compared to paraprofessional visitors who shared many of the social characteristics of the families they served.

Programme content

The nurses had three major goals: 1) to improve the outcomes of pregnancy by helping women improve their prenatal health; 2) to improve the child’s subsequent health and development by helping parents provide more competent care; and 3) to improve parents’ life-course by helping them develop visions for their futures and then make smart choices about planning future pregnancies, completing their educations, and finding work. In the service of these goals, the nurses helped women build supportive relationships with family members and friends, and linked families with other services.

The nurses followed detailed visit-by-visit guide-lines whose content reflects the challenges parents are likely to confront during specific stages of pregnancy and the first 2 years of the child’s life. Specific assessments were made of maternal, child, and family functioning that correspond to those stages, and specific activities were recommended based upon problems and strengths identified through the assessments.

During pregnancy, the nurses helped women complete 24-hour diet histories on a regular basis and plot weight gains at every visit; they assessed the women’s cigarette smoking and use of alcohol and illegal drugs and facilitated a reduction in the use of these substances through behavioural change strategies. They taught women to identify the signs and symptoms of pregnancy complications, encouraged women to inform the office-based staff about those conditions, and facilitated compliance with treatment. They gave particular attention to urinary tract infections, sexually transmitted diseases, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (conditions associated with poor birth outcomes). They co-ordinated care with physicians and nurses in the office and measured blood pressure when needed.

After delivery, the nurses helped mothers and other care-givers improve the physical and emotional care of their children. They taught parents to observe the signs of illness, to take temperatures, and to communicate with office staff about their children’s illnesses before seeking care. Curricula were employed to promote parent-child interaction by facilitating parents’ understanding of their infants’ and toddlers’ communicative signals, enhancing parents’ interest in interacting with their children to promote and protect their health and development.

Overview of research designs, methods, and findings

In each of the three trials, women were randomized to receive either home visitation services or comparison services. While the nature of the home visitation services was essentially the same in each of the trials as described above, the comparison services were slightly different. Both studies employed a variety of data sources. The Elmira sample (n=400) was primarily white. The Memphis sample (n=1138 for pregnancy and 743 for the infancy phase) was primarily black. The Denver trial (n=735) consisted of a large sample of Hispanics and systematically examined the impact of the programme when delivered by paraprofessionals (individuals who shared many of the social characteristics of the families they served) and by nurses. We looked for consistency in programme effect across those sources before assigning much importance to any one finding. Unless otherwise stated, all findings reported below were significant at the P≤0.05 level using two-tailed tests.

Elmira results

Prenatal health behaviours

During pregnancy, compared to their counterparts in the control group, nurse-visited women improved the quality of their diets to a greater extent, and those identified as smokers smoked 25% fewer cigarettes by the 34th week of pregnancy (Olds, Henderson, Tatelbaum, and Chamberlin 1986). By the end of pregnancy, nurse-visited women experienced greater informal social support and made better use of formal community services.

Pregnancy and birth outcomes

By the end of pregnancy, nurse-visited women had fewer kidney infections, and, among women who smoked, those who were nurse-visited had 75% fewer preterm deliveries, and among very young adolescents (aged 14–16), those who were nurse-visited had babies who were 395 g heavier, than their counterparts assigned to the comparison group (Olds, Henderson, Tatelbaum, and Chamberlin 1986).

Sensitive, competent care of child

At 10 and 22 months of the child’s life, nurse-visited poor, unmarried teens, in contrast to their counterparts in the control group, exhibited less punishment and restriction of their infants and provided more appropriate play materials than did their counterparts in the control group (Olds, Henderson, Chamberlin, and Tatelbaum 1986). At 34 and 46 months of life, nurse-visited mothers provided home environments that were more conducive to their children’s emotional and cognitive development and that were safer (Olds, Henderson, and Kitzman 1994).

Child abuse, neglect, and injuries

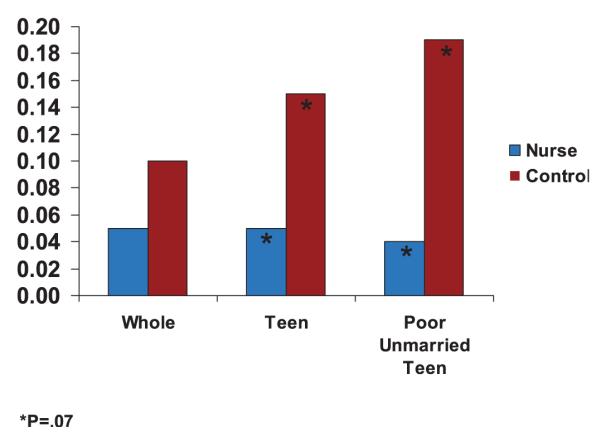

During the first 2 years of the child’s life, nurse-visited children born to low-income, unmarried teens had 80% fewer verified cases of child abuse and neglect than did their counterparts in the control group (1 case or 4% of the nurse-visited teens, versus 8 cases or 19% of the control group, P=0.07). Figure 2 shows how the treatment-control differences were greater among families where there was more concentrated social disadvantage. While these effects were only a trend, the effects among the poor, unmarried teens were corroborated by observations of mothers’ treatment of their children in their homes and injuries detected in the children’s medical records. During the second year of life, nurse-visited children were seen in the emergency department 32% fewer times, a difference that was explained in part by a 56% reduction in visits for injuries and ingestions.

Figure 2.

Rates of verified cases of child abuse and neglect by treatment condition, and socio-demographic characteristics of sample. Indicated cases of child abuse and neglect – 0 to 2 years Elmira. Source: © Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics Vol. 78, Page 65-78, Copyright #1986 by the AAP

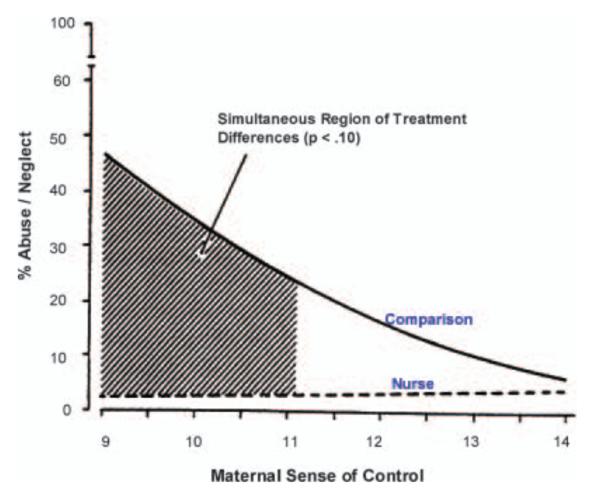

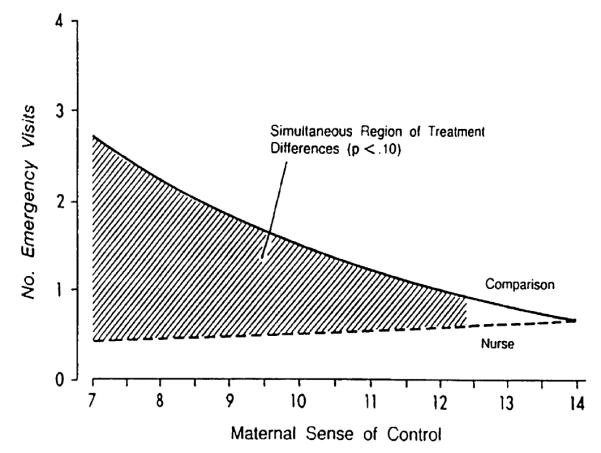

As shown in Figures 3 and 4, the effect of the programme on child abuse and neglect in the first 2 years of life and on emergency department encounters in the second year of life was greatest among children whose mothers had little belief in their control over their lives when they first registered for the programme during pregnancy. This set of findings deepened our conviction that the nurses’ emphasis on supporting women’s development of self-efficacy was a crucial element of the programme.

Figure 3. Rates of verified cases of child abuse and neglect (birth to age 2) by treatment condition and maternal sense of control measured at registration during pregnancy (Elmira).

Source: Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics Vol. 78, Page 75, Copyright ©1986 by the AAP

Figure 4. Rates of emergency department encounters in children’s second years of life by treatment condition and maternal sense of control measured at registration during pregnancy.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics Vol. 78, Page 75, Copyright ©1986 by the AAP

During the 2 years after the programme ended, its impact on health care encounters for injuries endured: irrespective of risk, children of nurse-visited women were less likely than their control group counterparts to receive emergency room treatment and to visit a physician for injuries and ingestions (Olds, Henderson, and Kitzman 1994). The impact of the programme on state-verified cases of child abuse and neglect, on the other hand, disappeared during that 2-year period (Olds, Henderson, and Kitzman 1994), probably because of increased detection of child abuse and neglect in nurse-visited families and nurses’ linkage of families with needed services (including child protective services) at the end of the programme (Greene 2001).

Results from a 15-year follow-up of the Elmira sample (Olds, Eckenrode, et al. 1997) indicate that the treatment-comparison differences in rates of state-verified reports of child abuse and neglect grew between the children’s 4th and 15th birthdays. Overall, during the 15-year period after delivery of their first child, in contrast to women in the comparison group, those visited by nurses during pregnancy and infancy were identified as perpetrators of child abuse and neglect in an average of 0.29 versus 0.54 verified reports per programme participant, an effect that was greater for women who were poor and unmarried at registration (Olds, Eckenrode, et al. 1997).

Childneuro-developmental impairment

At 6 months of age, nurse-visited poor unmarried teens reported that their 6-month old infants were less irritable and fussy than did their counterparts in the comparison group (Olds, Henderson, Chamberlin, and Tatelbaum 1986). Subsequent analyses of these data indicated that these differences were really concentrated among infants born to nurse-visited women who smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day during pregnancy in contrast to babies born to women who smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day in the comparison group (Conrad 2006). Over the first 4 years of the child’s life, children born to comparison group women who smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day during pregnancy experienced a 4–5-point decline in intellectual functioning in contrast to comparison group children whose mothers smoked 0–9 cigarettes per day during pregnancy (Olds, Henderson, and Tatelbaum 1994a). In the nurse-visited condition, children whose mothers smoked 0–9 cigarettes per day at registration did not experience this decline in intellectual functioning, so that at ages 3 and 4 their IQ scores on the Stanford Binet test were about 4–5 points higher than their counterparts in the comparison group whose mothers smoked 10+ cigarettes per day at registration (Olds, Henderson, and Tatelbaum 1994b).

Early parental life-course

By the time the first child was 4 year of age, nurse-visited, low-income, unmarried women, in contrast to their counterparts in the control group, had fewer subsequent pregnancies, longer intervals between births of first and second children, and greater participation in the work-force than did their comparison group counterparts (Olds, Henderson, Tatelbaum, and Chamberlin 1988).

Later parental life-course

At the 15-year follow-up, no differences were reported for the full sample on measures of maternal life-course such as subsequent pregnancies or subsequent births, the number of months between first and second births, receipt of welfare, or months of employment. Poor, unmarried women, however, showed a number of enduring benefits. In contrast to their counterparts in the comparison condition, those visited by nurses both during pregnancy and infancy averaged fewer subsequent pregnancies, fewer subsequent births, longer intervals between the birth of their first and second children, fewer months on welfare, fewer months receiving food stamps, fewer behavioural problems due to substance abuse, and fewer arrests (Olds, Eckenrode, et al. 1997).

Child/adolescent functioning

Among the 15-year-old children of study participants, those visited by nurses had fewer arrests and adjudications as persons in need of supervision (PINS). These effects were greater for children born to mothers who were poor and unmarried at registration. Nurse-visited children, as trends, reported fewer sexual partners and fewer convictions and violations of probation.

Memphis results

Prenatal health behaviours

There were no programme effects on women’s use of standard prenatal care or obstetrical emergency services after registration in the study. By the 36th week of pregnancy, nurse-visited women were more likely to use other community services than were women in the control group. There were no programme effects on women’s cigarette smoking, probably because the rate of cigarette use was only 9% in this sample.

Pregnancy and birth outcomes

In contrast to women in the comparison group, nurse-visited women had fewer instances of pregnancy-induced hypertension, and, among those with the diagnosis, nurse-visited cases were less serious (Kitzman et al. 1997).

Sensitive, competent care of child

Nurse-visited mothers reported that they attempted breast-feeding more frequently than did women in the comparison group, although there were no differences in duration of breast-feeding. By the 24th month of the child’s life, in contrast to their comparison group counterparts, nurse-visited women held fewer beliefs about child-rearing associated with child abuse and neglect. Moreover, the homes of nurse-visited women were rated on as more conducive to children’s development. While there was no programme effect on observed maternal teaching behaviour, children born to nurse-visited mothers with low levels of psychological resources were observed to be more communicative and responsive toward their mothers than were their comparison group counterparts (Kitzman et al. 1997).

Child abuse, neglect, injuries, and death

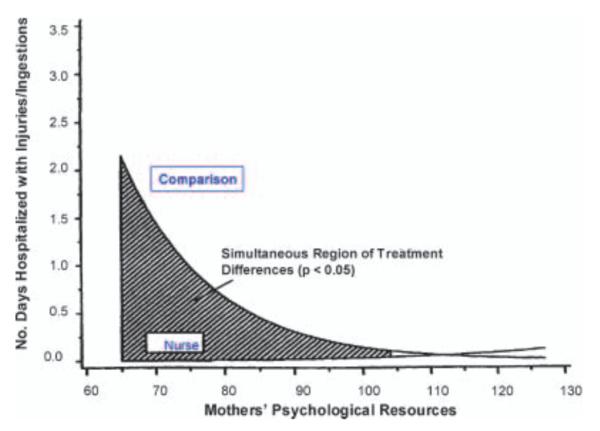

The rate of substantiated child abuse and neglect in the population of 2-year-old, low-income children in Memphis was too low (3%–4%) to serve as a valid indicator of child maltreatment in this study. We therefore hypothesized that we would see a pattern of programme effects on childhood injuries similar to that observed in Elmira. During their first 2 years, compared to children in the comparison group, nurse-visited children had 23% fewer health care encounters for injuries and ingestions and were hospitalized for 79% fewer days with injuries and/or ingestions, effects that were more pronounced for children born to mothers with few psychological resources (Figure 5). Nurse-visited children tended to be older when hospitalized and to have less severe conditions. The reasons for hospitalizations suggest that many of the comparison group children suffered from more seriously deficient care than children visited by nurses (Table 1).

Figure 5. Regressions of number of days hospitalized on mothers’ psychological resources fitted separately for nurse-visited and control group mothers (Memphis).

Source: Advances in Infancy Research Vol 12. Rovee-Collier, C., Lipsitt, L.P., & Hayne, H. Copyright © 1998 by Ablex Publishing Corp. Reproduced with permission of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., Westport, CT.

Table 1.

Diagnoses for hospitalizations for injuries or ingestions among nurse-visited and control group children in the first two years of life (Memphis)

| Diagnosis | Age, mo | Sex | Length of Stay, d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse-Visited (Treatment Group 4) | |||

| Burns (1st and 2nd degree to face) | 12.0 | M | 2 |

| Coin ingestion | 12.1 | M | 1 |

| Ingestion of iron medication | 20.4 | F | 4 |

|

| |||

| Comparison (Treatment Group 2) | |||

| Head trauma | 2.4 | M | 1 |

| Fractured fibula/congenital syphilis | 2.4 | M | 12 |

| Strangulated hernia with delay in seeking care/burns (1st degree to lips) |

3.5 | M | 15 |

| Bilateral subdural hematoma* | 4.9 | F | 19 |

| Fractured skull | 5.2 | F | 5 |

| Bilateral subdural hematoma (unresolved)/aseptic meningitis—2nd hospitalization* |

5.3 | F | 4 |

| Fractured skull | 7.8 | F | 3 |

| Coin ingestion | 10.9 | M | 2 |

| Child abuse/neglect suspected | 14.6 | M | 2 |

| Fractured tibia | 14.8 | M | 2 |

| Burns (2nd degree to face/neck) | 15.1 | M | 5 |

| Burns (2nd and 3rd degree to bilateral leg)† | 19.6 | M | 4 |

| Gastroenteritis/head trauma | 20.0 | F | 3 |

| Burns (splinting/grafting)—2nd hospitalization† | 20.1 | M | 6 |

| Finger injury/osteomyelitis | 23.0 | M | 6 |

One child was hospitalized twice with a single bilateral subdural hematoma.

One child was hospitalized twice for burns resulting from a single incident.

Source: Reproduced with permission from JAMA, vol. 278, Page 650, Copyright © 1997 by the American Medical Association

We chose not to hypothesize that the programme would affect the rates of mortality among nurse-visited children because death is too infrequently occurring to serve as a reliable outcome. Nevertheless, we (Olds, Kitzman, Hanks, et al. 2007) found that as a trend, by child age 9, nurse-visited children were less likely to have died than their control-group counterparts (P=0.08). The rates of death were 4.5 times higher in the control group than in the group visited by nurses. Table 2 displays the rates and reasons for death among nurse-visited and control-group children.

Table 2.

Rates and causes of infant and child deaths (International Classification of Diseases) among first-born children through age 9

| Treatment group | Treatment comparisons | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Nurse-visited | Comparison versus nurse | ||||

| n=498 | n=222 | P-value | Odds ratio (CI) | |||

| 10 (20.08) | 1 (4.50) | 0.080 a | 0.22 (0.03, 1.74) | |||

| No. of deaths (rate/1000) |

Cause of death (ICD9 code) | Age at death (days) |

Cause of death (ICD9 code) |

Age at death (days) |

||

| Extreme prematurity (7650) | 3 | Chromosomal abnormalities (7589) |

24 | |||

| Sudden infant death syndrome (7980) | 20 | |||||

| Sudden infant death syndrome (7980) | 35 | |||||

| Ill-defined intestinal infections (90) | 36 | |||||

| Sudden infant death syndrome (7980) | 49 | |||||

| Multiple congenital anomalies (7597) | 152 | |||||

| Chronic respiratory disease in arising in perinatal period (7707) |

549 | |||||

| Homicide assault by fire-arm (9654) | 1569 | |||||

| Motor vehicle accident (8129) | 2100 | |||||

| Accident caused by fire-arm (9229) | 2114 | |||||

This is the likelihood ratio P-value. The chi-square test probability is 0.116.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics Vol. 120, Page e842, Copyright © 2007 by the AAP

Child neuro-developmental impairment

By child age 6, compared to their counterparts in the control group, children visited by nurses had higher intellectual functioning and receptive vocabulary scores, and fewer behaviour problems in the border-line or clinical range. Nurse-visited children born to mothers with low psychological resources had higher arithmetic achievement test scores and expressed less aggression and incoherence in response to story stems. Though child age 9, nurse-visited children born to mothers with low psychological resources had higher grade point averages in reading and math than did their counterparts in the control group (Olds, Kitzman, Hanks, et al. 2007).

Early parental life-course

At the 24th month of the first child’s life, nurse-visited women reported fewer second pregnancies and fewer subsequent live births than did women in the comparison group. Nurse-visited women and their first-born children relied upon welfare for slightly fewer months during the second year of the child’s life than did comparison group women and their children (Kitzman et al. 1997).

Later parental life-course

During the 4.5-year period following birth of the first child, in contrast to control-group counterparts, women visited by nurses had fewer subsequent pregnancies, fewer therapeutic abortions, and longer durations between the birth of the first and second child; fewer total person-months (based upon administrative data) that the mother and child used aid to families with dependent children (AFDC) and food stamps; higher rates of living with a partner and living with the biological father of the child; and partners who had been employed for longer durations (Kitzman et al. 2000). By child age 6, women visited by nurses continued to have fewer subsequent pregnancies and births; longer intervals between births of first and second children; longer relationships with current partners; and since last follow-up at 4.5 years, fewer months of using welfare and food stamps. They also were more likely to register their children in formal out-of-home care between age 2 and 4.5 years (82.0% versus 74.9%) (Olds, Kitzman, Cole, et al. 2004). By the time the first-born child was 9 years of age, nurse-visited women continued to have longer intervals between the births of first and second children, fewer cumulative subsequent births, and longer relationships with their current partners. From birth through child age 9, nurse-visited women continued to use welfare and food stamps for fewer months (Olds, Kitzman, Hanks, et al. 2007).

Denver results

In the Denver trial, we were unable to use the women’s or children’s medical records to assess their health because the health care delivery system was too complex to reliably abstract all of their health care encounters as we had done in Elmira and Memphis. Moreover, as in Memphis, the rate of state-verified reports of child abuse and neglect was too low in this population (3%–4% for low-income children, from birth to 2 years of age) to allow us to use Child Protective Service records to assess the impact of the programme on child maltreatment. We therefore focused more of our measurement resources on the early emotional development of the infants and toddlers.

Denver results for paraprofessionals

There were no paraprofessional effects on women’s prenatal health behaviour (use of tobacco), maternal life-course, or child development, although at 24 months, paraprofessional-visited mother-child pairs in which the mother had low psychological resources interacted more responsively than did control-group counterparts. Moreover, while paraprofessional-visited women did not have statistically significant reductions in the rates of subsequent pregnancy, the reductions observed were clinically significant (Olds, Robinson, O’Brien, et al. 2002). By child age 4, mothers and children visited by paraprofessionals, compared to controls, displayed greater sensitivity and responsiveness toward one another and, in those cases in which the mothers had low psychological resources at registration, had home environments that were more supportive of children’s early learning. Children of low resource women visited by paraprofessionals had better behavioural adaptation during testing than their control-group counterparts (Olds, Robinson, Pettitt, et al. 2004).

Denver results for nurses

The nurses produced effects consistent with those achieved in earlier trials of the programme.

Prenatal health behaviours

In contrast to their control-group counterparts, nurse-visited smokers had greater reductions in urine cotinine (the major nicotine metabolite) from intake to the end of pregnancy (Olds, Robinson, O’Brien, et al. 2002).

Sensitive, competent care of child

During the first 24 months of the child’s life, nurse-visited mother-infant dyads interacted more responsively than did control pairs, an effect concentrated in the low-resource group. As trends, nurse-visited mothers provided home environments that were more supportive of children’s early learning (Olds, Robinson, O’Brien, et al. 2002).

Child neuro-developmental impairment

At 6 months of age, nurse-visited infants, in contrast to control-group counterparts, were less likely to exhibit emotional vulnerability in response to fear stimuli, and those born to women with low psychological resources were less likely to display low emotional vitality in response to joy and anger stimuli. At 21 months, nurse-visited children were less likely to exhibit language delays than were children in the control group, an effect again concentrated among children born to mothers with low psychological resources. Nurse-visited children born to women with low psychological resources also had superior language and mental development in contrast to control-group counterparts (Olds, Robinson, O’Brien, et al. 2002). At child age 4, nurse-visited children whose mothers had low psychological resources at registration, compared to control-group counterparts, had more advanced language, superior executive functioning, and better behavioural adaptation during testing (Olds, Robinson, Pettitt, et al. 2004).

Early maternal life-course

By 24 months after delivery, nurse-visited women, compared to controls, were less likely to have had a subsequent pregnancy and birth and had longer intervals until the next conception. Women visited by nurses were employed longer during the second year following the birth of their first child than were controls (Olds, Robinson, O’Brien, et al. 2002). By child age 4, nurse-visited women continued to have greater intervals between the birth of their first and second children, less domestic violence, and enrolled their children less frequently in either preschool, Head Start, or licensed day care than did controls (Olds, Robinson, Pettitt, et al. 2004).

Cost savings

The Washington State Institute for Public Policy has conducted a thorough economic analysis of prevention programmes from the standpoint of their impact on crime, substance abuse, educational outcomes, teen pregnancy, suicide, child abuse and neglect, and domestic violence (Aos et al. 2004). While this analysis does not cover all outcomes that have cost implications for the NFP (such as the rates and outcomes of subsequent pregnancies or maternal employment), it provides a consistent examination of all programmes that have attempted to affect the listed outcomes. This report sums the findings across all three trials of the NFP and estimates that it saves $17,000 per family. This estimate is consistent with a subsequent analysis produced by the Rand Corporation (Karoly et al. 2005).

Policy implications and programme replication

One of the clearest messages from this programme of research is that the functional and economic benefits of the nurse home visitation programme are greatest for families at greater risk. In Elmira, it was evident that most married women and those from higher socio-economic households managed the care of their children without serious problems and that they were able to avoid lives of welfare dependence, substance abuse, and crime without the assistance of the nurse home visitors. Low-income, unmarried women and their children in the control group on the other hand, were at much greater risk for these problems, and the programme was able to avert many of these untoward outcomes for this at-risk population. This pattern of results challenges the position that these kinds of intensive programmes for targeted at-risk groups ought to be made available on a universal basis. Not only is it likely to be wasteful from an economic standpoint, but it may lead to a dilution of services for those families who need them the most, because of insufficient resources to serve everyone well.

Replication and scale-up of the Nurse-Family Partnership

Even when communities choose to develop programmes based on models with good scientific evidence, such programmes run the risk of being watered down in the process of being scaled up. So, it was with some apprehension that our team began to make the programme available for public investment in new communities (Olds, Hill, O’Brien, et al. 2003). Since 1996, the Nurse-Family Partnership national office has helped new communities develop the programme outside of traditional research contexts so that today the programme is operating in 330 counties in the United States, serving over 14,400 families per day. State and local governments are securing financial support for the Nurse-Family Partnership (about $11,000 per family for 2.5 years of services, in 2008 dollars) out of existing sources of funds, such as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, Medicaid, the Maternal and Child Health Block-Grant, and child-abuse and crime-prevention dollars.

Capacities necessary to support dissemination

Each site choosing to implement the Nurse-Family Partnership needs certain capacities to operate and sustain the programme with high quality. These capacities include having an organization and community that are fully knowledgeable and supportive of the programme; a staff that is well trained and supported in the conduct of the programme model; and real-time information on implementation of the programme and its achievement of bench-marks to guide efforts in continuous quality improvement. Staff members at the NFP National Service Office are organized to help create these state and local capacities.

International replication

Our approach to international replication of the programme is to make no assumptions about its possible benefits in societies that have different health and human service delivery systems and cultures than those in which the programme was tested in the United States. Given this, our team has taken the position that the programme ought to be adapted and tested in other societies before it is offered for public investment. We currently are working with partners in England, Holland, Germany, Australia, and Canada to adapt and test the programme with disadvantaged populations. While it is possible that the need and impact of this intervention may be diminished in societies with more extensive health and social welfare systems than are found in the United States, it is possible that the programme may have comparable effects for subgroups that do not make good use of those other services and resources that are available to them.

Acknowledgements

The work reported here was made possible by support from many different sources. These include the Administration for Children and Families (90PD0215/01 and 90PJ0003), Biomedical Research Support (PHS S7RR05403-25), Bureau of Community Health Services, Maternal and Child Health Research Grants Division (MCR-360403-07-0), Carnegie Corporation (B-5492), Colorado Trust (93059), Commonwealth Fund (10443), David and Lucile Packard Foundation (95-1842), Ford Foundation (840-0545, 845-0031, and 875-0559), Maternal and Child Health, Department of Health and Human Services (MCJ-363378-01-0), National Center for Nursing Research (NR01-01691-05), National Institute of Mental Health (1-K05-MH01382-01 and 1-R01-MH49381-01A1), Pew Charitable Trusts (88-0211-000), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (179-34, 5263, 6729, 9677, and 35369), US Department of Justice (95-DD-BX-0181), and the W. T. Grant Foundation (80072380, 84072380, 86108086, and 88124688).

I thank John Shannon for his support of the programme and data gathering through Comprehensive Interdisciplinary Developmental Services, Elmira, New York; Robert Chamberlin and Robert Tatelbaum for contributions to the early phases of this research; Jackie Roberts, Liz Chilson, Lyn Scazafabo, Georgie McGrady, and Diane Farr for their home visitation work with the Elmira families; Geraldine Smith for her supervision of the nurses in Memphis; Jann Belton and Carol Ballard for integrating the programme into the Memphis/Shelby County Health Department; Kim Arcoleo and Jane Powers for their work on the Elmira and Memphis trials; Pilar Baca, Ruth O’Brien, JoAnn Robinson, and Susan Hiatt, the many home visiting nurses in Memphis and Denver; and the participating families who have made this programme of research possible.

References

- Aos S, Lieb R, Mayfield J, Miller M, Pennucci A. Benefits and Costs of Prevention and Early Intervention Programs for Youth. Washington State Institute for Public Policy; Olympia, WA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Tremblay RE, Boulerice B, Saucier JF. Obstetrical Complications and Violent Delinquency: Testing Two Developmental Pathways. Child Development. 2002;73:496–508. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aytaclar S, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Lu S. Association between Hyperactivity and Executive Cognitive Functioning in Childhood and Substance Use in Early Adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:172–178. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: (National Institute of Drug Abuse Monograph 56).Familial Antecedents of Adolescent Drug Use: A Developmental Perspective. 1987 (DHHS Publication No. ADM 87-1335) [PubMed]

- Biglan A, Duncan TE, Ary DV, Smolkowski K. Peer and Parental Influences on Adolescent Tobacco Use. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1995;18:315–330. doi: 10.1007/BF01857657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Offord DR, Racine YA, Szatmari P, Fleming JE, Links PS. Predicting Substance Use in Late Adolescence: Results from the Ontario Child Health Study Follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:761–767. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD. Does Stress Damage the Brain? Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:797–805. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Vermetten E. Neuroanatomical Changes Associated with Pharmacotherapy in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2004;1032:154–157. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Developmental ecology through space and time: a future perspective. In: Moen P, Elder GHJ, Luscher K, editors. Examining Lives in Context. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Clark AS, Soto S, Bergholz TSM. Maternal Gestational Stress Alters Adaptive and Social Behavior in Adolescent Rhesus Monkey Offspring. Infant Behavior and Development. 1996;19:453–463. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Cornelius J. Childhood Psychopathology and Adolescent Cigarette Smoking: A Prospective Survival Analysis in Children at High Risk for Substance Use Disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:837–841. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Cornelius JR, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Childhood Risk Categories for Adolescent Substance Involvement: A General Liability Typology. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Pollock N, Bukstein OG, Mezzich AC, Bromberger JT, Donovan JE. Gender and Comorbid Psychopathology in Adolescents with Alcohol Dependence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1195–1203. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Navaline H, Metzger D. High-Risk Behaviors for HIV: A Comparison between Crack-Abusing and Opioid-Abusing African-American Women. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1994;26:233–241. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1994.10472436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole R, Henderson CRJ, Kitzman H, Anson E, Eckenrode J, Sidora K. Long-Term Effects of Nurse Home Visitation on Maternal Employment. 2004. Unpublished manuscript.

- Conrad C. Measuring Costs of Child Abuse and Neglect: A Mathematic Model of Specific Cost Estimations. Journal of Health & Human Services Administration. 2006;29:103–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezol S, Butterfield PM. Partners in Parenting Education. Denver, CO: 1994. How to Read Your Baby. [Google Scholar]

- Elster AB, McAnarney ER. Medical and Psychosocial Risks of Pregnancy and Childbearing during Adolescence. Pediatric Annals. 1980;9:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field TM, Scafidi F, Pickens J, Prodromidis M, Pelaez-Nogueras M, Torquati J, Wilcox H, Malphurs J, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Polydrug-Using Adolescent Mothers and their Infants Receiving Early Intervention. Adolescence. 1998;33:117–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, Watkinson B, Dillon RF, Dulberg CS. Neonatal Neurological Status in a Low-Risk Population after Prenatal Exposure to Cigarettes, Marijuana, and Alcohol. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1987;8:318–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Brooks-Gunn J, Morgan SP. Adolescent Mothers in Later Life. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, O’Koon JH, Davis TH, Roache NA, Poindexter LM, Armstrong ML, Minden JA, McIntosh JM. Protective Factors Affecting Low-Income Urban African American Youth Exposed to Stress. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2000;20:388–417. [Google Scholar]

- Greene JP. High School Graduation Rates in the United States: Revised. Manhattan Institute for Policy Research; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Paul Brookes; Baltimore, MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and Protective Factors for Alcohol and Other Drug Problems in Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Implications for Substance Abuse Prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Fombonne E, Poulton R, Martin J. Differences in Early Childhood Risk Factors for Juvenile-Onset and Adult-Onset Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:215–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V, Pandina RJ. Familial and Personal Drinking Histories and Measures of Competence in Youth. Addictive Behaviors. 1991;16:453–465. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90053-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoly LA, Kilburn MR, Cannon JS. Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise. RAND; Santa Monica, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Kessler RC. The Impact of Childhood Psychopathology Interventions on Subsequent Substance Abuse: Policy Implications, Comments, and Recommendations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1303–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman H, Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Hanks C, Cole R, Tatelbaum R, McConnochie KM, Sidora K, Luckey DW, Shaver D, Engelhardt K, James D, Barnard K. Effect of Prenatal and Infancy Home Visitation by Nurses on Pregnancy Outcomes, Childhood Injuries, and Repeated Childbearing. A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:644–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman H, Olds DL, Sidora K, Henderson CR, Jr, Hanks C, Cole R, Luckey DW, Bondy J, Cole K, Glazner J. Enduring Effects of Nurse Home Visitation on Maternal Life Course: A 3-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:1983–1989. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS. Intrauterine Growth and Gestational Duration Determinants. Pediatrics. 1987;80:502–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R. The Stability of Antisocial and Delinquent Child Behavior: A Review. Child Development. 1982;53:1431–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Slutske WS, Madden PA, Nelson EC, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Escalation of Drug Use in Early-Onset Cannabis Users vs Co-Twin Controls. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:427–433. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in Infancy, Childhood, and Adulthood: A Move to the Level of Representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes LC. Neurobiology of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure: Effect on Developing Monoamine Systems. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1994;15:121–133. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan SS, Carlson MJ. Welfare Reform, Fertility, and Father Involvement. The Future of Children. 2002;12:146–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. Is Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy a Risk Factor for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:1138–1142. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.9.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-Limited and Life-Course-Persistent Antisocial Behavior: A Developmental Taxonomy. Psychological Reviews. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL. Tobacco Exposure and Impaired Development: A Review of the Evidence. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 1997;3:257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL. Prenatal and Infancy Home Visiting by Nurses: from Randomized Trials to Community Replication. Prevention Science. 2002;3:153–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1019990432161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL. The Nurse-Family Partnership: An Evidence-Based Preventive Intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:5–25. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL. Preventing Crime with Prenatal and Infancy Support of Parents: The Nurse-Family Partnership. Victims and Offenders. 2007;2:205–225. doi: 10.1080/14043850802450096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Jr, Kitzman H, Powers J, Cole R, Sidora K, Morris P, Pettitt LM, Luckey D. Long-Term Effects of Home Visitation on Maternal Life Course and Child Abuse and Neglect. Fifteen-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Chamberlin R, Tatelbaum R. Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect: A Randomized Trial of Nurse Home Visitation. Pediatrics. 1986;78:65–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Kitzman H. Does Prenatal and Infancy Nurse Home Visitation Have Enduring Effects on Qualities of Parental Caregiving and Child Health at 25 to 50 Months of Life? Pediatrics. 1994;93:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Tatelbaum R. Intellectual Impairment in Children of Women who Smoke Cigarettes during Pregnancy. Pediatrics. 1994a;93:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Tatelbaum R. Prevention of Intellectual Impairment in Children of Women who Smoke Cigarettes during Pregnancy. Pediatrics. 1994b;93:228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CRJ, Tatelbaum R, Chamberlin R. Improving the Delivery of Prenatal Care and Outcomes of Pregnancy: A Randomized Trial of Nurse Home Visitation. Pediatrics. 1986;77:16–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Henderson CRJ, Tatelbaum R, Chamberlin R. Improving the Life-Course Development of Socially Disadvantaged Mothers: A Randomized Trial of Nurse Home Visitation. American Journal of Public Health. 1988;78:1436–1445. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.11.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Hill PL, O’Brien R, Racine D, Moritz P. Taking Preventive Intervention to Scale: The Nurse-Family Partnership. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2003;10:278–290. [Google Scholar]

- Olds D, Kitzman H, Cole R, Robinson J, Sidora K, Luckey D, Henderson C, Hanks C, Bondy J, Holmberg J. Effects of Nurse Home Visiting on Maternal Life-Course and Child Development: Age-Six Follow-up of a Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1550–1559. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Kitzman H, Hanks C, Cole R, Anson E, Sidora-Arcoleo K, Luckey DW, Henderson CR, Jr, Holmberg J, Tutt RA, Stevenson AJ, Bondy J. Effects of Nurse Home Visiting on Maternal and Child Functioning: Age-9 Follow-up of a Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e832–845. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Robinson J, O’Brien R, Luckey DW, Pettitt LM, Henderson CR, Jr, Ng RK, Sheff KL, Korfmacher J, Hiatt S, Talmi A. Home Visiting by Paraprofessionals and by Nurses: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Pediatrics. 2002;110:486–496. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Robinson J, Pettitt L, Luckey DW, Holmberg J, Ng RK, Isacks K, Sheff K. Effects of Home Visits by Paraprofessionals and by Nurses: Age-Four Follow-up of a Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1560–1568. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Sadler L, Kitzman H. Programs for Parents of Infants and Toddlers: Recent Evidence from Randomized Trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:355–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overpeck MD, Brenner RA, Trumble AC, Trifiletti LB, Berendes HW. Risk Factors for Infant Homicide in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339:1211–1216. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810223391706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson L, Gable S. Holistic injury prevention. In: Lutzker JR, editor. Handbook of Child Abuse Research and Treatment. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS. Affective Neuroscience and the Development of Social Anxiety Disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;24:689–705. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS. Developmental Psychobiology and Response to Threats: Relevance to Trauma in Children and Adolescents. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;53:796–808. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R. Development, Genetics, and Psychology. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Brennan P, Mednick SA. Birth Complications Combined with Early Maternal Rejection at Age 1 Year Predispose to Violent Crime at Age 18 Years. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:984–988. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon DW. The Behavior of Infants whose Mothers Smoke in Pregnancy. Early Human Development. 1978;2:363–369. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(78)90063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood B, Delaney-Black V, Covington C, Nordstrom-Klee B, Ager J, Templin T, Janisse J, Martier S, Sokol RJ. Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Childhood Behavior at Age 6 to 7 Years: I. Dose-Response Effect. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E34. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Sampson PD, Barr HM, Bookstein FL, Olson HC. The effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol and tobacco: contributions from the Seattle longitudinal prospective study and implications for public policy. In: Needleman HL, Bellinger D, editors. Prenatal Exposure to Toxicants: Developmental Consequences. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Cornelius JR, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, Gardner W, Blackson T, Clark D. Neurobehavioral Disinhibition in Childhood Predicts Early Age at Onset of Substance Use Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1078–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]