Abstract

S K-edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) was performed on wild type Cp rubredoxin and its Cys->Ser mutants in both solution and lyophilized forms. For wild type rubredoxin and for the mutants where an interior cysteine residue (C6 or C39) is substituted by serine, a normal solvent effect is observed, that is, the S covalency increases upon lyophilization. For the mutants where a solvent accessible surface cysteine residue is substituted by serine, the S covalency decreases upon lyophilization which is an inverse solvent effect. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations reproduce these experimental results and show that the normal solvent effect reflects the covalency decrease due to solvent H-bonding to the surface thiolates and that the inverse solvent effect results from the covalency compensation from the interior thiolates. With respect to the Cys->Ser substitution, the S covalency decreases. Calculations indicate that the stronger bonding interaction of the alkoxide with the Fe relative to that of thiolate increases the energy of the Fe d orbitals and reduces their bonding interaction with the remaining cysteines. The solvent effects support a surface solvent tuning contribution to electron transfer and the Cys->Ser result provides an explanation for the change in properties of related iron-sulfur sites with this mutation.

Introduction

Numerous enzymes feature iron-sulfur sites that are key for reactivity.1–3 These enzymes perform a wide variety of functions including electron transfer, substrate activation and DNA repair. The Fe-S bonds are highly covalent, and a modulation of this covalency in the protein can contribute to the redox properties of the site.4,5 Our previous studies on ferredoxin and HiPIP indicated that solvent access can change the covalency of the Fe4S4 sites through water H-bonding to the sulfur ligands and thus tune the reduction potential.6

Fe-S bond covalency can be directly probed by sulfur K-edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS).7,8 S K-edge XAS measures a transition from the sulfur 1s orbital to unoccupied valence orbitals that have sulfur p character. For a complex with covalent bonding between S and a transition metal ion, the S K-edge spectrum can have a pre-edge feature corresponding to the transition from S 1s to the unoccupied or half-occupied metal d orbitals, which can be expressed as:

| (1) |

The intensity of the pre-edge transition can be used to quantify the covalency, i.e. the S character, α2, in the predominately metal based Ψ*d orbital using9

| (2) |

where I(S1s→S3p) is the intrinsic intensity of a sulfur 1s→3p transition.

The energy of the pre-edge transition reflects the energy difference between the metal d and sulfur 1s orbital. For thiolate complexes, the energy of the sulfur 1s orbital can be viewed as fairly constant over similar complexes. Therefore the pre-edge energy reflects the energy of the unoccupied metal d orbitals which are dependent on the effective nuclear charge (Zeff) of the metal and on the ligand field strength.8

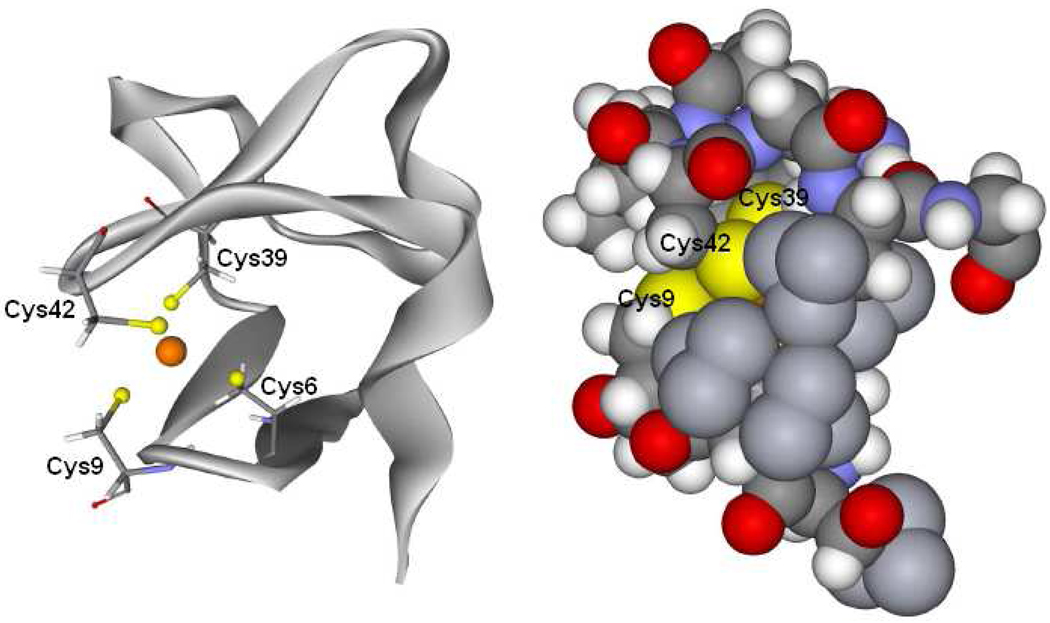

Rubredoxin is an iron-sulfur protein involved in electron transfer and contains a mononuclear Fe center bound by four cysteine residues in a pseudo Td geometry.10,11 The FeS4 site is located at the surface of the protein and the two surface thiolates are solvent accessible12 (Figure 1). Rubredoxin is the simplest iron-sulfur site and thus provides an appropriate system for evaluating the effect of the solvent on the covalency of the site and its contribution to the reduction potential.

Figure 1.

Left is a schematic structure of rubredoxin and its active site and right is a space filling model around the active site. Cys42 and Cys9 are at the surface and solvent accessible.

In rubredoxin, the surface thiolate ligands C42 and C9 and the interior ligands C39 and C6 have been individually mutated to serine.13 These mutations can help evaluate the solvent effect since only the surface ligands have solvent accessibility. In addition, mutation of a cysteine ligand to serine significantly affects the reduction potential. Previous work14 found a reduction potential decrease of ~200mV for the surface mutants and ~100mV for the interior mutants.

In our earlier study we compared the S K-edge XAS of Rd to that of an appropriate model and found the pre-edge intensity to significantly decrease in the protein relative to that of the model.15 In the present study, S K-edge XAS is extended to evaluate the contribution of the solvent to this intensity change, the effect of Cys->Ser substitution at all four ligand positions and the effects of the solvent on these variants. These studies show different solvent effects for WT Rd and the interior mutants relative to the exterior mutants and through correlation to DFT calculations support the solvent tuning model presented in reference 6.

Experimental Details

Sample Preparation

The Clostridium pasteurianum Rd protein and all mutants were expressed and purified as described previously.13 The WT and C42S Rd were >95% pure as judged by SDS-PAGE and electrospray mass spectrometry. For S K-edge XAS measurements, the protein solutions (2 mM protein solution in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.5) were pre-equilibrated in a water-saturated He atmosphere for ~1 h to minimize bubble formation in the sample cell. Samples were loaded via a syringe into a Pt-plated Al block sample holder, sealed in front using a 6.3 µm polypropylene window and maintained at a constant temperature of 4 °C during data collection using a controlled flow of N2 gas, pre-cooled by liquid N2 passing through an internal channel in the Al block.

RdCp and its mutants were lyophilized by spinning the 2 mM protein solution under vacuum at −44°C. The lyophilized samples were ground into a fine powder and dispersed as thinly as possible on sulfur-free Mylar tape. The sample was then mounted across the window of a 1 mm thick aluminum plate for the S K-edge XAS measurements. The reversibility of the lyophilization and grounding process was tested by dissolving the resultant powder in the same buffer and measuring its S K-edge XAS.

S K-edge XAS Data Collection and Analysis

All sulfur K-edge data were measured at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory using the 54-pole wiggler beam line 6-2. Details of the experimental configuration for low-energy studies have been described previously.8 The photon energy was calibrated to the maximum of the first pre-edge feature of Na2S2O3•5H2O at 2472.02 eV. A total of 3–5 scans were measured per sample to ensure reproducibility. Raw data were calibrated and averaged using EXAFSPAK.16 Using the PySpline program17, the background was removed from all spectra by fitting a second-order polynomial to the pre-edge region and subtracting it from the entire spectrum. Normalization of the data was accomplished by fitting a flat second-order polynomial or straight line to the post-edge region and normalizing the edge jump to 1.0 at 2490.0 eV. The error from background subtraction and normalization is less than 1%. Intensities of the pre-edge features were quantified by fitting the data with pseudo-Voigt line shapes with a fixed 1:1 ratio of Lorentzian to Gaussian contributions, using the EDG_FIT program.16 The reported intensity values are based on the average of 10–12 good fits. The error from the fitting procedure is less than 1%. The fitted intensities were converted to %S3p character using the pre-edge feature of plastocyanin as a reference where 1.02 units of intensity correspond to 38% S3p character.18 The uncertainty in pre-edge energy is ~0.1 eV.19

Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

Resonance Raman spectra were obtained in a ~135° backscattering configuration using a Coherent Innova Sabre 25/7 Ar+ CW ion laser. The 568.2 nm laser line with an incident power of 45 mW was used as the excitation source. Scattered light was dispersed through a Spex 1877 CP triple monochromator with 1200, 1800, and 2400 grooves/mm holographic gratings and detected with an Andor Newton charge-coupled device (CCD) detector cooled to −80°C. Samples were contained in a 4 mm NMR tube immersed in a liquid nitrogen finger dewar for measurements. All samples were stable under prolonged laser irritation. Raman energies were calibrated using Na2SO4 and citric acid. Background spectra were obtained using a buffer solution at 77 K for baseline subtraction in the same type of NMR tube. Frequencies are accurate to within 2 cm−1.

DFT Calculations

All calculations were performed on dual Intel Xeon workstations using the Gaussian 03 package20. The geometries of the active sites of the proteins were optimized with the unrestricted BP86 functional21,22 using the 6-311G* basis set on the Fe, S, and alkoxide O atoms and 6-31G* on the remaining atoms. The starting coordinates for WT Rd were obtained from the published crystal structure with 1.2 Å resolution (PDB id: 5XRN)13. The protein was truncated to 114 atoms. To model the C42S and C39S mutants, the corresponding S atom in the WT Rd model was changed to O. For the C6S mutant, an H atom was added to terminate the S atom of Ser6 and a OH− was added as the fourth ligand. To model the solvent effect, two water molecules were added to the surface side of the optimized structure, one water molecule near each surface ligand. These discrete H2Os interact with the lone pair on each of the solvent exposed donor ligands. The backbone of each structure was constrained in the optimization to maintain the confirmation of the protein. Single point calculations using a 6-311+G* basis set on Fe, S, and alkoxide O atoms and 6-311G* on the remaining atoms were performed on optimized geometries with the tight convergence criteria. Mulliken23–26 and CSPA27 population analyses were performed using the PyMolyze program28 to calculate the covalencies. TD-DFT calculations were performed with the electronic structure program ORCA29,30 with the same basis sets and functional as the single point calculations.

Results

A. S K-edge Data for Wild Type Rubredoxin

The S K-edge XAS data for wild type (WT) Cp Rd in solution and in lyophilized form are presented in Figure 2 (dashed and solid lines respectively). Previously published S K-edge data for a model complex FeIII(S2-o-xyl)2 15 are included for comparison (red).

Figure 2.

S K-edge XAS data for WT Rd with and without solvent and a model complex15.

WT Rd in solution has a well-resolved pre-edge feature centered at 2470.2 eV. Contributions from the transitions to the two half-occupied e orbitals and three half-occupied t2 orbitals are not resolved due to the low value of 10 Dq in the pseudo Td ligand field. The pre-edge intensity corresponds to 33% S3p mixing into the unoccupied Fe3d orbitals (i.e. covalency) from each thiolate (Table 1), consistent with the previous study15.

Table 1.

Pre-edge transition energy, intensity and covalency results from S K-edge data.

| Sample | Energy (eV) | Intensity | Half-width | Covalency per S(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeIII(S2-o-xyl)2a | 2470.4 | − | − | 38 |

| WT lyo | 2470.2 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 36 |

| WT soln | 2470.2 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 33 |

| C42S lyo | 2470.5 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 30 |

| C42S soln | 2470.5 | 0.82 | 0.54 | 33 |

| C9S lyo | 2470.4 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 33 |

| C9S soln | 2470.4 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 36 |

| C6S lyo | 2470.2 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 30 |

| C6S soln | 2470.3 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 19 |

| C39S lyo | 2470.4 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 20 |

| C39S soln | 2470.4 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 17 |

Published results 15

Lyophilized WT Rd shows a pre-edge feature at 2470.2 eV, which is not shifted in energy from that of WT in solution, within the resolution of S K-edge XAS (~0.1 eV). The pre-edge intensity of lyophilized WT Rd corresponds to 36% S covalency. Compared with WT Rd in solution, lyophilized WT Rd shows an increase in pre-edge intensity, paralleling the behavior of Fe4S4 ferredoxin. As for ferredoxin, this increase in S covalency when solvent is removed for Rd can be attributed to loss of H-bonding from solvent water.6

Compared with the model complex, both WT solution and lyophilized WT have a pre-edge transition lower in intensity and in energy, reflecting less donation from thiolates and a weaker ligand field.

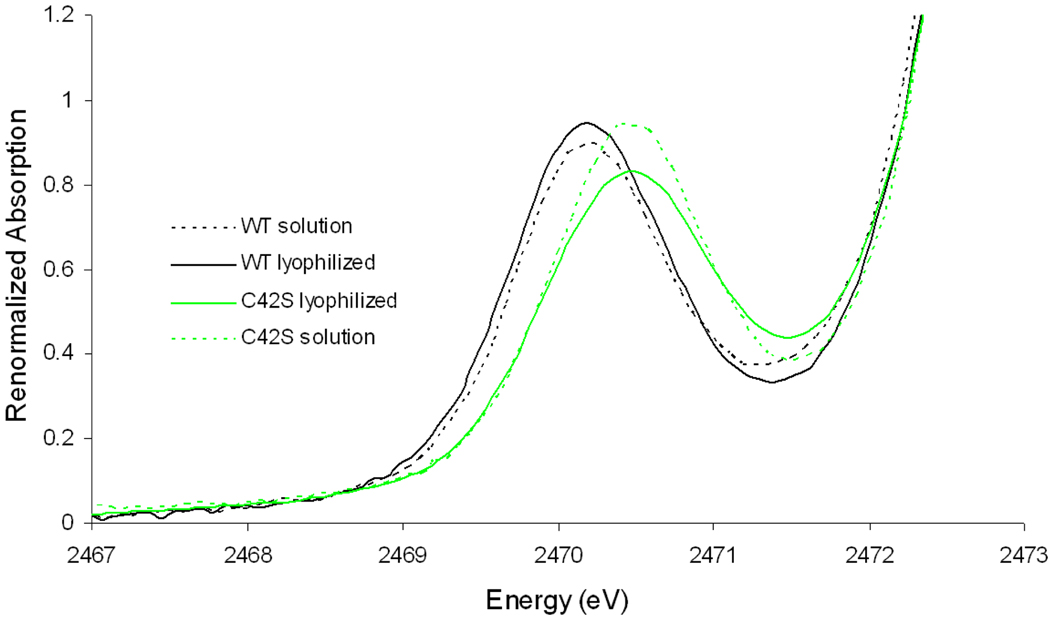

B. S K-edge Data for the Surface Mutants

The S K-edge XAS data for the surface mutant C42S in solution are presented in Figure 3. This surface mutant has a pre-edge feature at 2470.5 eV and a pre-edge intensity corresponding to 33% S covalency. The integrated intensity of C42S in solution is equivalent to that of WT in solution but the peak of C42S is narrower. The width of the peak reflects the e/t2 splitting by the ligand field. Since the lyophilized WT and C42S have the same peak width, the narrower pre-edge for C42S in solution relative to WT in solution is consistent with fact that solvent H-bonding to an alkoxide is stronger than for a thiolate (see Analysis section C) and more significantly decreases the ligand field.

Figure 3.

Comparison of S K-edge data for C42S and WT rubredoxin with and without solvent.

Lyophilized C42S shows a pre-edge feature at 2470.5 eV with a pre-edge intensity which corresponds to 30% S covalency. Compared with the data for the C42S solution, lyophilized C42S shows a decrease in pre-edge intensity. Therefore, in contrast with WT Rd (included for comparison as black lines in Figure 3) and Fe4S4 ferredoxin, C42S has a solvent effect in the opposite direction (i.e. an “inverse” solvent effect) where the S K pre-edge intensity decreases upon loss of water.

This “inverse” solvent effect can be explained by a change in charge compensation7,31–34. In C42S Rd in solution, water can form H-bonds to both the surface serine and surface cysteine ligands decreasing their donation, i.e. covalency. Lyophilization eliminates these H-bonds and would increase the surface ligand donor interaction with the Fe. This increase in surface ligand covalency is compensated by a decrease in the covalency from the interior cysteine ligands. The covalency decrease from the two interior thiolates exceeds the covalency increase from the one surface thiolate. Since only S covalency is measured in S K-edge XAS, the C42S mutant shows a net decrease in pre-edge intensity upon lyophilization.

The pre-edge feature of the other surface mutant, C9S, is quite similar to that of C42S. C9S has the pre-edge transition at 2470.4 eV for both the lyophilized and solution forms and also shows an “inverse” solvent effect. (Figure S1) Since the S K-edge spectra for C9S parallel those for C42S and are of poorer quality, they are not analyzed further.

C. Comparison of Lyophilized WT and C42S

Since the solvent effect on WT and C42S Rds are in the opposite direction, their lyophilized forms are now compared to elucidate the effect of the Cys->Ser mutation. Comparing the S K-edge XAS of lyophilized WT to that of lyophilized C42S Rd (Figure 3), the pre-edge transition shifts up in energy by 0.3 eV indicating that the d manifold has increased in energy. Thus the alkoxide acts as a stronger ligand than thiolate. The pre-edge intensity of lyophilized C42S is lower than that of lyophilized WT Rd. Thus the donation of the alkoxide ligand causes the thiolate ligands to donate less per thiolate. From the compensation effect mentioned above, this indicates that alkoxide acts as a stronger donor ligand than the thiolate it replaced.

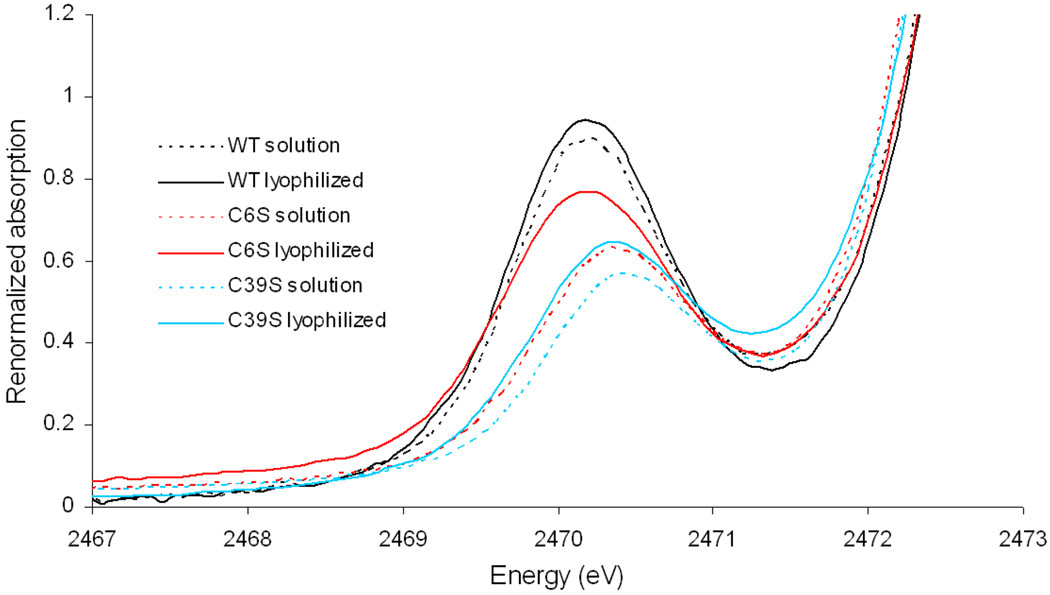

D. S K-edge Data for the Interior Mutants

The S K-edge data for the interior mutants C6S and C39S are presented in Figure 4. The interior mutants have considerably lower than 100% metal loading35 due to lower stability. Therefore the S K-edge intensities cannot be compared to WT Rd. Alternatively their energies and the change in energy and intensity of a specific mutant with lyophilization can be reasonably compared.

Figure 4.

Comparison of S K-edge data for interior mutants and WT rubredoxin with and without solvent.

Both interior mutants show the normal solvent effect of WT Rd, i.e. the pre-edge intensity increases upon lyophilization. This is consistent with the fact that both surface ligands in the interior mutants are thiolates as in WT and the covalency from these ligands increases upon loss of water H-bonds. However, the difference between the lyophilized form and solution is discontinuously large in C6S. A previous study showed that in contrast to the other three mutants, C6S has a hydroxide ligand rather than the mutated serine, i.e. an FeIII(S-Cys)3(OH) center.14 It is possible that lyophilization of C6S leads to loss of the OH− ligand and the three thiolates donate more charge to compensate for this ligand loss.

In parallel to the C42S and C9S mutants, the pre-edge transition in C39S is higher in energy than in WT reflecting a stronger ligand field when alkoxide is bound. However, while C6S Rd in solution also shows a pre-edge transition higher in energy than that of WT, reflecting the stronger OH− ligand, the pre-edge transition energy of lyophilized C6S is about the same as that of WT. This would also be consistent with the loss of the OH− ligand in lyophilized C6S Rd.

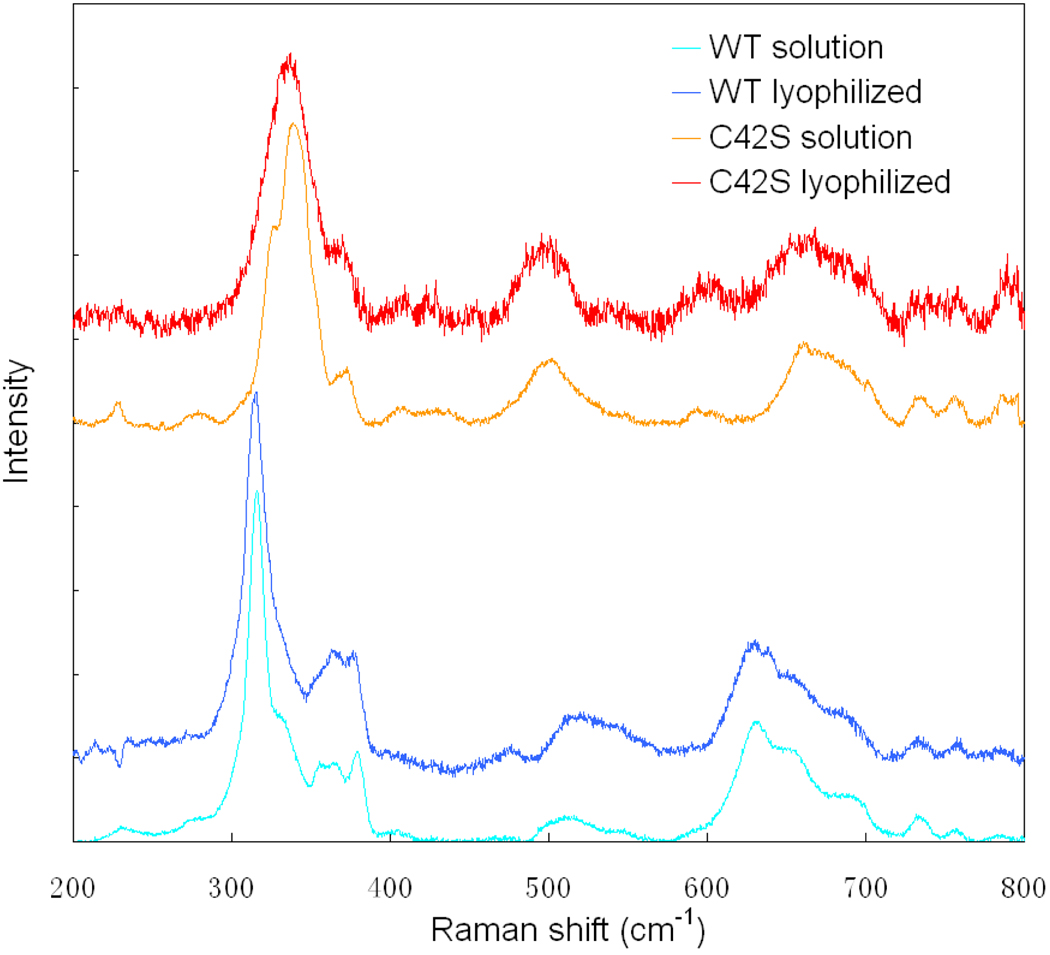

E. Resonance Raman for WT and C42S

It has been suggested that S covalency can change in FeS sites due to conformational change of the thiolate ligands.36 This is best probed by resonance Raman spectroscopy which is sensitive to the Fe-S-C-C dihedral angle.

Spiro and coworkers have shown that the Fe-S stretching frequency can change by as much as 43 cm−1 when the dihedral angle is changed.37 Therefore, we performed resonance Raman studies on WT and C42S Rd in both solution and lyophilized forms. The spectra are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Resonance Raman spectra for WT and C42S rubredoxin with and without solvent.

The resonance Raman spectra for WT Rd in solution and C42S Rd in solution are consistent with those reported in previous studies38,39. WT has four features associated with Fe-S stretching in the range 290–400 cm−1; the 315 cm−1 intense peak assigned to the Fe-S breathing mode ν1(FeS4) and 356 cm−1, 367 cm−1 and 380 cm−1 are assigned to the triply degenerate T2 mode in Td which splits due to symmetry lowering in Rd.39 C42S exhibits three bands14 in the range 310–390 cm−1 associated with one Fe-S breathing mode v1(FeS3) and the doubly degenerate E mode which splits due to symmetry lowering from C3v.

From our resonance Raman spectra in Figure 5, for both WT and C42S there is no observable change in any of the Fe-S frequencies when either protein is lyophilized.40,41 Therefore, there is no significant change in the FeS-CC dihedral angles upon lyophilization and thus the observed covalency changes are not caused by a conformational change of the Rd site.

Analysis

A. DFT Modeling

A.1. Geometry Optimizations

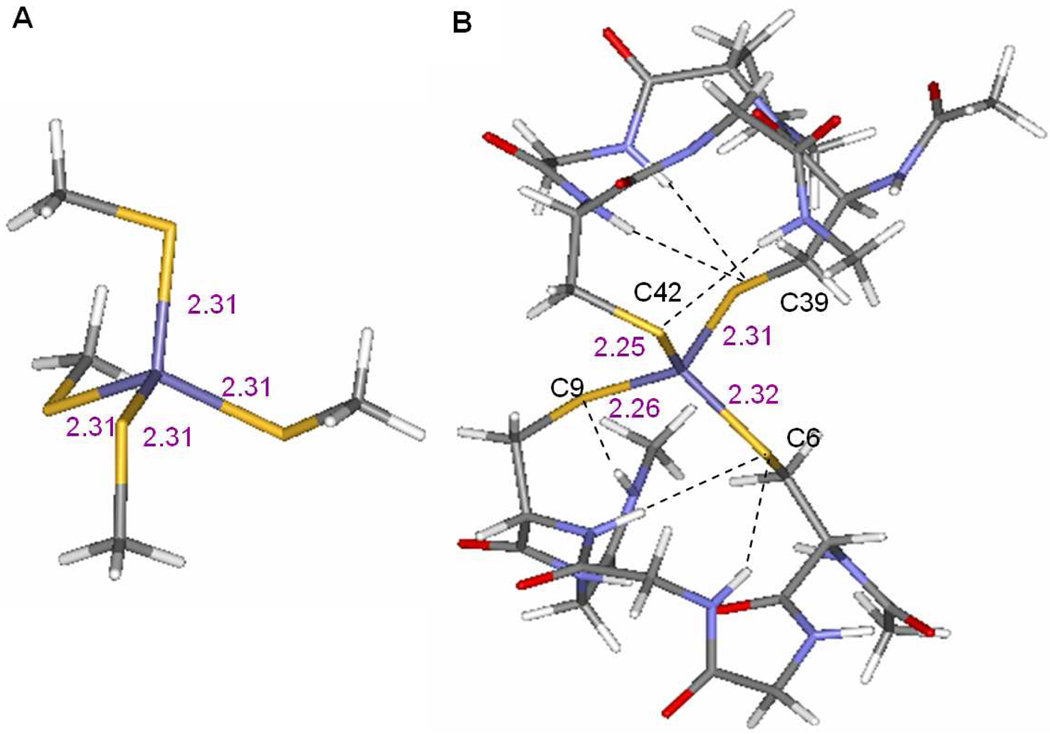

Geometry optimizations for the WT Rd were performed using both a small and a large model of the active site. The small model is an Fe(SMe)4 complex in pseudo Td symmetry (Figure 6A). The large model is from the crystal structure of WT Rd (PDB id: 5XRN, Figure 6B) and includes the backbone of the peptides which form six H-bonds to the thiolates (a total of 114 atoms). To maintain the confirmation of the backbone in the large model, the oxygen atoms on the backbone and the four terminal carbon atoms of the peptide chains (capped with H atoms) were constrained in the optimization.

Figure 6.

Structures of of A) the small model and B) the large model used in DFT calculations.

The DFT optimized Fe-S bond lengths are listed in Table 2 together with the bond lengths from crystallography13. The optimized structure for the small model has four identical Fe-S bond lengths while for the large model the surface Fe-S bond lengths are shorter than the interior bond lengths, consistent with the crystallographic results for WT. The longer interior Fe-S bondlengths are consistent with the different number of H-bonds from protein backbone (two H-bonds for each interior thiolate and one for each surface thiolate)42. Therefore, the protein backbone in the large model is essential for reproducing the differences between the surface and interior ligands in the rubredoxin site. The large model was employed for all DFT calculations on Rd.

Table 2.

DFT optimized and experimental Fe-S and Fe-O bond lengths (in Å).

| External | Internal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-S(C42) | Fe-S(C9) | Fe-S(C6) | Fe-S(C39) | |

| WT_Expa | 2.25 | 2.29 | 2.33 | 2.31 |

| WT | 2.25 | 2.26 | 2.32 | 2.31 |

| WT+2water | 2.26 | 2.26 | 2.31 | 2.30 |

| C42S_Expb | 1.94 (O) | 2.29 | 2.29 | 2.31 |

| C42S | 1.84 (O) | 2.26 | 2.34 | 2.32 |

| C42S+2water | 1.85 (O) | 2.26 | 2.34 | 2.32 |

| C39S | 2.26 | 2.29 | 2.34 | 1.90 (O) |

| C6S_OH | 2.26 | 2.26 | 1.87 (O) | 2.35 |

From crystallographic data in 5XRN.pdb

From crystallographic data in 1BE7.pdb

Since the surface ligands C42 and C9 have about the same Fe-S bond length and the S K-edge data for C42S and C9S are also quite similar, only C42S is calculated to represent the surface mutants. To model the C42S and C39S mutants, the corresponding S atom in the large model for WT was changed to O. The C6S mutant was modeled with a FeIII(S-Cys)3(OH) center.

To simulate WT Rd and the mutants in solution, two water molecules were added to the surface side of the optimized large model, one water molecule near each surface ligand with the O atom ~3.3 Å away from the thiolate S or ~2.9 Å from the serine O and one OH bond of the H2O orientated toward the S/O atom. This structure was then optimized with only the backbone oxygen atoms and the four terminal carbon atoms frozen. In the optimized structures, water forms H-bonds with the surface thiolates at a distance of ~3.28 Å (water O to thiolate S atom) or with the surface alkoxide at a distance of 2.74 Å (from water O to alkoxide). From Table 2, adding water molecules did not considerably change the Fe-S and Fe-O bond length (≤0.01Å). Thus the average bond lengths calculated from the large model without water can be compared with the average bond lengths determined from EXAFS13 to evaluate the results of the optimization calculations. From Table 3, the calculated Fe-S and Fe-O bond lengths agree well with those from the EXAFS data.

Table 3.

Fe-S and Fe-O bond lengths (in Å) from EXAFS and DFT.

| EXAFS | DFT | EXAFS | DFT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-S | Fe-S | Fe-O | Fe-O | |

| WT | 2.274 | 2.28 | ||

| C42S | 2.290 | 2.31 | 1.836 | 1.84 |

| C39S | 2.281 | 2.30 | 1.865 | 1.90 |

| C6S | 2.280 | 2.29 | 1.869 | 1.87 |

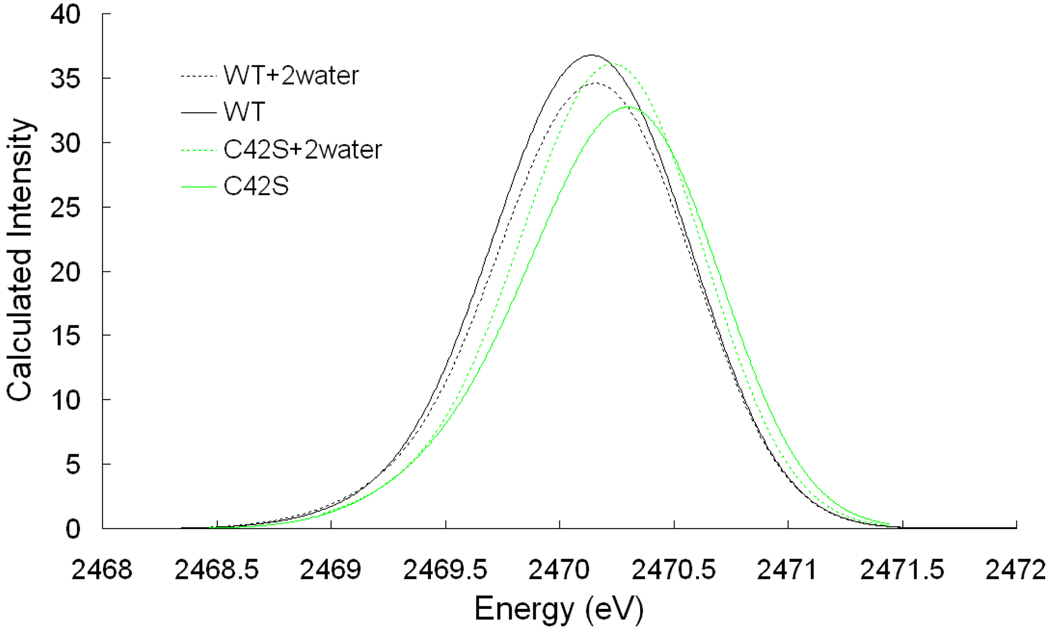

A.2. Simulation of S K-edge Data and CSPA Population Analysis

TD-DFT calculations and CSPA (c-squared population analysis)27 were performed on the optimized structures above. The results are given in Table 4 and Figure 7. The rationale for using C1SPA is addressed in section D.

Table 4.

DFT calculated S covalency and TD-DFT calculated pre-edge intensity.

| SCPA Covalency | TD-DFT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | C42 | C9 | C6 | C39 | intensitya | |

| WT | 31.5 | 34.7 | 33.8 | 27.5 | 29.5 | 46.5 |

| WT_2water | 29.5 | 30.4 | 29.7 | 27.8 | 30.1 | 43.8 |

| C42S | 27.5 | 18.8 (O) | 33.4 | 23.4 | 25.8 | 41.7 |

| C42S_2water | 29.6 | 18.6 (O) | 33.7 | 27.4 | 27.6 | 43.8 |

| C39S_ | 29.0 | 30.7 | 31.1 | 25.2 | 15.4 (O) | |

| C6S_OH | 28.3 | 32.0 | 27.1 | 12.0 (O) | 25.90 | |

Normalized to intensity per one S.

Figure 7.

TD-DFT calculated pre-edge region of S K-edge XAS.

From WT to WT+2water, CSPA predicts a decrease in covalency from 31.5% to 29.5%, consistent with the decrease from 36% to 33% in S K-edge XAS data in figure 2 and Table 1. In comparing C42S to C42S+2water, the CSPA calculated covalency predicts an increase from 27.5% to 29.6%, again in agreement with the increase from 30% to 33% in the S K-edge XAS data in Figure 3. In comparing the calculated WT to C42S models, the covalency decreases from 31.5% to 27.5%, consistent with the change from 36% to 30% in experimental S K-edge XAS data.

TD-DFT calculation results also show a decrease in intensity in comparing the WT to WT+2water models, an increase in intensity in comparing the C42S to C42S+2water models, and a decrease in intensity between WT and C42S, in good agreement with S K-edge XAS data and CSPA calculations. The TD-DFT calculations also reproduced the shift-up in pre-edge transition energy from WT to C42S, indicating that alkoxide is a stronger donor ligand than thiolate (Figure 7).

In the DFT calculated structures, addition of 2 H2O to the WT and to the C42S structures predicts no noticeable change in Cys confirmation (See Table S1), consistent with the resonance Raman results. Therefore, the covalency change observed in calculations and experiment can be attributed to the H-bonding interaction with the water molecules.

B. The Normal and Inverse Solvent Effects

The DFT calculations reproduced the normal solvent effect for WT and the inverse solvent effect for C42S Rd observed experimentally in Figure 3 and Table 1. From Table 4, addition of 2 H2O to the WT model decreases the covalency from the two surface thiolates due to the additional H-bonding. While the covalency of the interior thiolates increases to partially compensate, the net effect is a decrease in covalency, i.e. the “normal” solvent effect.

From Table 4, upon addition of 2 H2O to the surface residues of C42S, the covalency from the surface alkoxide decreases due to water H-bonding while the covalency from the thiolates increases to compensate, giving the inverse solvent effect. Compared to WT, the compensation from the interior ligands is much larger in C42S. In addition, although the surface thiolate (C9) forms an H-bond with water, its covalency also increases slightly. This can be explained by the fact that the H-bonding to alkoxide is stronger and requires increased thiolate compensation. However, the O coefficient decreases by only a limited amount (from 18.8% to 18.6% in Table 4). In the next section we address why the limited change in alkoxide bonding can lead to a significant compensation for the inverse solvent effect.

C. Alkoxide Relative to Thiolate Donation

In comparing the S K-edge XAS data for C42S to those of WT Rd, the S covalency decreases, suggesting that alkoxide O is a better donor, resulting in less thiolate donation. The calculations in Table 4 reproduce this effect and show that there are two contributions to this decrease in thiolate S donation. First, C42 is a surface ligand which has a shorter Fe-S bond length and thus increased covalency relative to the interior thiolates. So when C42 is replaced by a serine O, even if the covalency from the other three thiolates was unchanged, the average S covalency would decrease. Second, the alkoxide substitution also causes the net covalency of the remaining three thiolates to decrease.

In C39S and C6S Rd, one interior thiolate is replaced by an alkoxide or hydroxide, respectively. The interior thiolates have longer Fe-S bonds and lower covalencies relative to the surface thiolates, so if the alkoxide did not change the covalencies of the other three thiolates, the average S covalency would increase relative to WT Rd. While differences in loading preclude an experimental probe of this substitution, DFT calculations show a decrease, not increase in the net thiolate S covalency. Consistent with this, both the DFT calculations and EXAFS experimental data show an increase in the average Fe-S bond length upon alkoxide substitution. Therefore, when alkoxide (or OH−) is substituted for an interior thiolate ligand, the spectator thiolates donate less.

Therefore, replacing either the surface or the interior thiolate with an alkoxide (or OH−) decreases the covalency of the other thiolates, indicating that the alkoxide (or OH−) is a better donor. However, the CSPA analysis in Table 4 shows that the covalency (i.e. amount of donation) from the alkoxide (or OH−) O is only 12%–18.8%, much less than the ~30% covalency from each of the thiolate S’s. Thus the alkoxide O contributes less than thiolate S to the wavefunction but decreases the donation from the remaining thiolate ligands.

From the experimental S K-edge XAS data and the TD-DFT calculations, substitution of the thiolate with the alkoxide ligand (both surface and interior) shifts the S1s->Fe 3d transitions, thus the 3d orbitals, up in energy. Below we evaluate the origin of this increase in Fe 3d orbital energy and the impact of this shift on the spectator thiolate donation.

We consider the bonding of one Fe 3d orbital |Fe> to three thiolate S and one alkoxide O orbital. The wavefunction of the Fe based orbital Ψ*Fe can be expressed as a linear combination of these orbitals:

| (3) |

The energy of Ψ*Fe (E*Fe) is obtained by solving the secular determinant

| (4) |

where the overlaps between the ligands are considered to be zero. HFeFe, HSS and HOO are estimated from atomic orbital ionization energies (−7.9 eV for the Fe 3d orbital43, −11.7 eV for S 3p and −15.9 eV for O 2p).44 HFeS and HFeO are the resonance integrals which relate to the ligand-metal overlap and are estimated by matching the coefficients of the solutions of Ψ *Fe to the experimental S K-edge XAS covalencies, for the FeS4 WT model (where Eq. 4 is expressed with four S ligands) and the FeS3O variant. (Details are included in the Supporting Information.)

The results are given in Table 5. In going from an FeS4 to an FeS3O site, the energy of the d orbital E*Fe increases by 0.2 eV, O has a smaller mixing coefficient (i.e. covalency) than S (~7% vs. ~9%) and the mixing coefficient of the three sulfurs (i.e. their net covalency) decreases (from 9.0% to 8.5%), as observed in the DFT calculations and in experiment.

Table 5.

Calculated energy (in eV) and covalency of an averaged Fe 3d orbital.

| FeS4 | FeS3O | |

|---|---|---|

| HFeFe | −9.7 | −9.7 |

| HSS | −11.7 | −11.7 |

| HOO | − | −15.9 |

| HFeS | −1.9 | −1.9 |

| HFeO | − | −3.0b |

| SFeS | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| SFeO | − | 0.1 |

| E*Fe | −8.2 | −8.0 |

| cS2 a | 9.0% | 8.5% |

| cO2 a | − | 6.8% |

From the DFT calculation only 4 Fe d orbitals has significant S character. Thus the 36% experimental covalency of lyophilized WT corresponds to 9% S covalency in each d orbital.

HFeO is lower in energy since HFeLα (HFeFe+HLL)SFeL (L=O or S) and HOO is larger in magnitude than HSS.

To understand this behavior, a simplified two atom system, ML, is considered. For this system

| (5) |

where ΔML = (HMM − HLL), λ is the ligand mixing coefficient. Eq. 5 indicates that in comparing the bonding interactions of a metal with alkoxide and with thiolate, since alkoxide O has p orbitals that are deeper in energy (i.e. HLL is more negative) relative to those of the S due to its higher electronegativity, ΔML is larger for the alkoxide and can shift higher in energy even with a smaller ligand mixing coefficient.

From the variational principle, the covalency in Eq. 3 can be estimated from Eq. 6:

| (6) |

(Supporting Information.) Thus a higher d orbital energy, E*Fe, (due to antibonding to the alkoxide) would decrease the mixing coefficient cS of the thiolate.

This model also suggests a mechanism for the covalency compensation observed in the S K-edge XAS data and calculations when water is added to C42S Rd. The water H-bonds decrease the alkoxide O mixing coefficient only from 18.8% to 18.6% (Table 4), however the H-bond to the alkoxide O is strong (−10 kcal/mol vs. −4 kcal/mol for thiolate45) and is reflected in the donation from the entire alkoxide ligand which decreases significantly (from 26.8% to 24.5%)46. This decreases the energy of the Fe d orbitals. DFT calculations predict a ~0.3 eV decrease in Fe 3d orbital energies and TD-DFT calculations predict a 0.07 eV decrease in pre-edge energy upon adding two H2O molecules to C42S.47 This decrease in Fe3d energy will increase the S covalency according to Eq. 6.

D. CSPA v.s. Mulliken Population Analysis

It has been reported that H-bonding from water does not significantly decrease the covalency for an Fe4S4 center using a Mulliken population analysis (MPA) on the Fe4S4 site.48 This led to the suggestion that the decrease in S K-edge intensity in Fe4S4 clusters upon lyophilization was due to an Fe-S-C-C conformational change.36 However, from the resonance Raman data in Results section E, such a conformational change does not occur for Rd upon lyophilization. We also observe no significant covalency decrease in the WT Rd model upon the addition of two H2Os using MPA. Alternatively for the Rd site, TD-DFT calculations predict the experimentally observed S K-edge intensity decrease and CSPA agrees with the S K-edge XAS data and the TD-DFT results in showing a covalency decrease.

Although MPA is the most widely used procedure, it has several issues limiting its utility for these studies. First, in MPA the overlap population (cacbSab) is equally divided between the two overlapping atoms. This is not particularly suitable for polar bonds like Fe-S. In addition, the covalency measured by S K-edge XAS does not reflect this division of valence electron density.

The pre-edge intensity of S K-edge XAS is proportional to8:

| (7) |

Since the overlap between a ligand centered core 1s orbital and a metal centered valence orbital is very small, (1− α2)1/2<Md|r|S1s> is negligible. The expression for the intensity becomes I(S1s→Md) ∝ α2|< S3p|r|S1s>|2. (See Eq. 2 in the Introduction.)

Thus valence electron density on the metal or in the overlap region between the metal and the ligand does not significantly contribute to the expectation value of <Ψ*d|r|S1s> due to the localization of the S 1s orbital. Since CSPA only uses the coefficient of the wavefunction27 and does not include the overlap population, it more directly correlates to S K-edge XAS than MPA.

E. Correlation of Reduction Potential to Covalency

To explore the solvent effect and the Cys->Ser mutation effect on the reduction potential of Rd, we calculated the ionization energies for WT Rd and for the mutants (Table 6). In going from the WT Rd model to the alkoxide and OH− mutants, the calculated ionization energy decreases by ~200 mV, contributing to the decrease in reduction potential observed experimentally14. This indicates that the alkoxide ligand stablizes FeIII more than the thiolate ligand it replaces. This is consistent with the results from section C indicating that in terms of bonding energy the alkoxide O is a stronger donor ligand than the thiolate S.

Table 6.

Comparison of calculated ionization energy and experimental reduction potential.

| Ionization energy (eV)a |

Reduction potentialb (mV) |

|

|---|---|---|

| WT | 0.66 | −77 |

| WT_2water | 1.03 | |

| C42S | 0.41 | −273 |

| C42S_2water | 0.89 | |

| C39S | 0.48 | ~−180 |

| C6S | 0.59 | −170 |

Ionization energy is calculated by subtracting the energy of the optimized reduced state from the energy of the optimized oxidized state.

Against NHE (Normal Hydrogen Electrode).

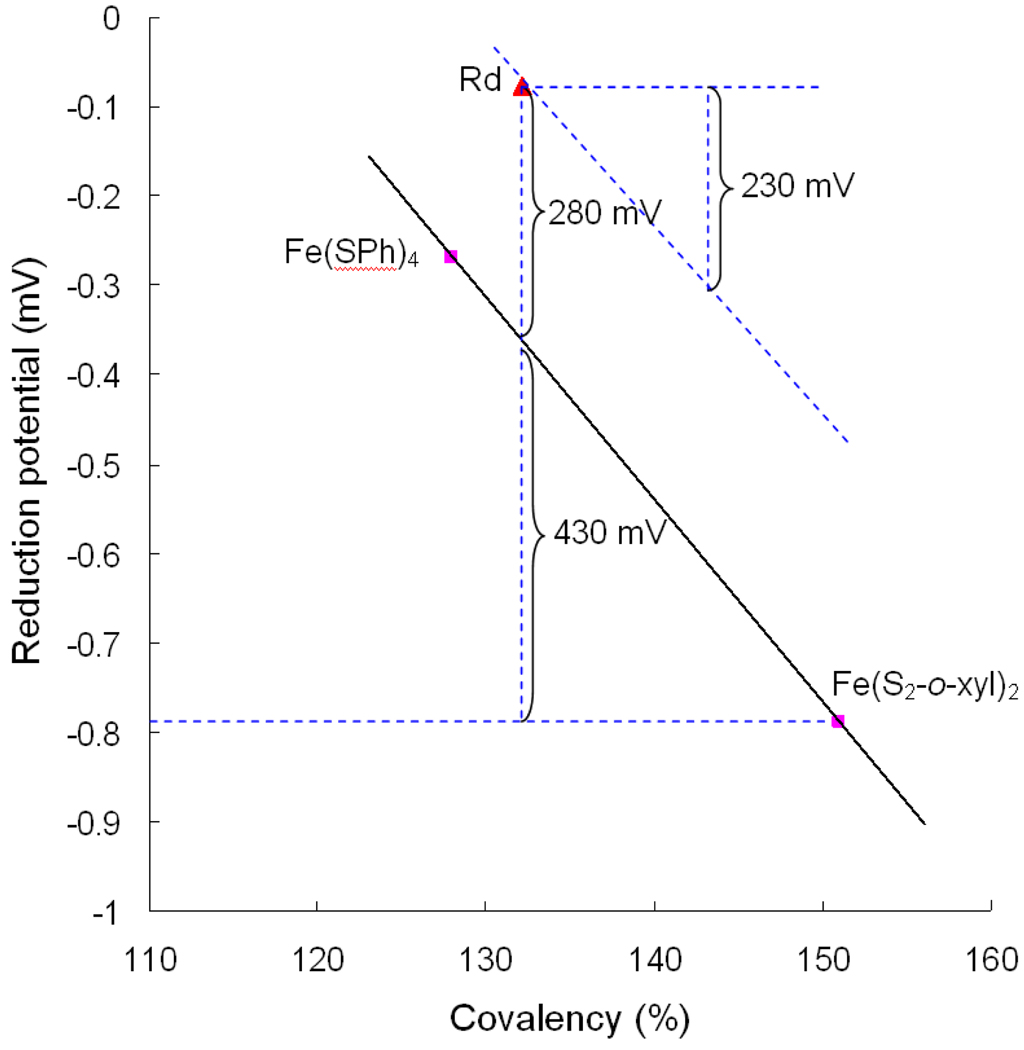

Importantly, the calculated ionization energies predict a 370 mV increase in reduction potential for WT Rd when water is included in the calculation and thus the covalency is decreased. From our past studies6,49,50, there is an approximately linear relationship between the covalency and reduction potential with a negative slope, indicating that a decreased covalent interaction between S and Fe will raise the reduction potential by destabilizing the oxidized state more than the reduced state. An estimate of this effect on the reduction potential of an FeS4 site is given in Figure 8, in which the covalencies derived from S K-edge XAS studies on FeIII(SPh)4 and FeIII(S2-o-xyl)2 are plotted relative to their corresponding one-electron reduction potentials (measured in DMF and scaled to NHE) and a linear dependence is assumed.

Figure 8.

Plot of the [FeS4]− reduction potential as a function of total Fe-S covalency. The difference in covalency between WT Rd ( ) and Fe(S2-o-xyl)2 (

) and Fe(S2-o-xyl)2 ( , lower right) corresponds to an ~430mV increase in reduction potential. The remaining ~280mV is from the asymmetric electrostatic environment around the site. The covalency increase due to lyophilization would correspond to a 230 mV decrease in reduction potential.

, lower right) corresponds to an ~430mV increase in reduction potential. The remaining ~280mV is from the asymmetric electrostatic environment around the site. The covalency increase due to lyophilization would correspond to a 230 mV decrease in reduction potential.

In going from FeIII(S2-o-xyl)2 to WT Rd in aqueous solution, the reduction potential increases from −790 mV to −77 mV while the total covalency (sum of the covalencies of the four thiolates) decreases by 19%. From the plot in Figure 8, this covalency decrease should result in approximately a +430 mV increase in the reduction potential. The remaining +280 mV contribution to the observed reduction potential of WT Rd would thus result from the additional stabilization of the reduced state by the asymmetric electrostatic field around the site and the effects of H-bonding. Based on the calculations of Warshel and co-workers51, this electrostatic stablization has 55% contribution from the charge and dipole on the protein, 33% from water dipole, and the rest from solvent dielectric. From this plot, the change in covalency observed due lyophilization,11%, predicts a 230 mV contribution to the potential of Rd due to the H-bonds of local H2O to the exterior thiolate ligands.

Discussion

Our S K-edge XAS data show that the Fe-S covalency increases for WT Rd and decreases for the C42S variant when the solvent is removed. While it is possible that such a covalency change would result from a conformation change induced by lyophilization, our resonance Raman data indicate that, in fact, no conformational change has occurred. Therefore, the change in covalency is attributed to the water H-bonding interaction with the surface thiolates. DFT calculations with H-bonded H2O molecules reproduce this covalency change with no conformational change and this is also observed in the TD-DFT calculations. This supports the model in reference 6 that loss of water H-bonding to the exterior ligands is the origin of the covalency change upon lyophilization. The interior and surface mutants also strongly support this model in that the solvent effect on the interior mutants is in the same direction as for the WT Rd (the covalency increases upon lyophilization) while for the surface mutants the solvent effect is in the opposite direction (the covalency decreases upon lyophilization). Thus the change in S K-edge intensity in all cases correlates with desolvation of the surface ligands upon lyophilization.

Since the reduction potential of iron-sulfur proteins is dependent on the Fe-S covalency and the covalency can be changed by water H-bonding to the ligands, the solvent can tune the reduction potential of iron-sulfur proteins. This is especially important for biological processes where an iron-sulfur protein binds another protein or DNA as a co-substrate. This binding can lead to the desolvation of the iron-sulfur active site and shift the reduction potential into the functional range for electron transfer. As an example relevant to this study, in the electron transfer chain for the oxygen reduction process in the anaerobic sulfate reducer Desulfovibrio gigas, the flavin center in rubredoxin-oxygen oxidoreductase (ROO) is reduced by Rd. The reduction potential of the flavin center is 0 mV for the quinone/semiquinone couple and −130 mV for the semiquinone/hydroquinone couple. The reduction potential of resting Rd is 0 ± 5 mV, which is not low enough for the second reduction of the flavin.52 A possible regulation mechanism for this electron transfer is that interaction with ROO may lead to desolvation of the Rd active site and thus decrease its reduction potential into the functional range.

With respect to the mutation effect of replacing a thiolate with an alkoxide ligand, the S K-edge intensity decreases even though the alkoxide O has a lower mixing coefficient. This reflects the fact that O is more electronegative than S and has its donor orbitals at deeper energy. In this bonding situation a lower contribution to the wavefunction can still reflect a stronger bonding interaction. Indeed the pre-edge is observed to shift up in energy in the four mutants (Figures 3 and 4). This will impact the compensation of the spectator ligands as higher energy d orbitals interact more weakly with these ligands. This increase in d orbital energy will also lower the reduction potential as observed experimentally for the alkoxide substituted mutants.

In the 2Fe ferredoxins, the Fe2S2 clusters are localized mixed valent in the reduced WT protein while in the Cys→Ser mutant of Clostridium Pasteurianum, the Fe2S2 clusters become delocalized.53–55 The present study provides insight into how this change could happen. When a thiolate ligand in the Fe2S2 site is replaced by an alkoxide, the alkoxide O can decrease the donation therefore the covalency of the bridging μ2-S2− and thus reduce the antiferromagnetic coupling which tends to keep the site localized. Reduced antiferromagnetic coupling could allow the double exchange to dominate, resulting in a delocalized site.

In summary, this study has shown that it is the solvent H-bonds to the surface ligands that are responsible for the changes in S K-edge intensity upon lyophilization. This supports the model in reference 6 that solvent can tune the reduction potential of iron-sulfur centers. Finally the alkoxide ligand is determined to be a stronger donor that can decrease the donor interaction of the remaining ligands and significantly impact the properties of an iron-sulfur site.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by NSF CHE-0948211 (E.I.S.) and Australian Research Council A29930204 (A.G.W.). SSRL operations are supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research. This publication was made possible by Grant Number 5 P41 RR001209 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: The complete reference for Gaussian 03, derivation of the wavefunction coefficients, S K-edge data for C9S Rd and the optimized geometries of the models. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Beinert H, Holm RH, Munck E. Science. 1997;277:653–659. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flint DH, Allen RM. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2315–2334. doi: 10.1021/cr950041r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukianova OA, David SS. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005;9:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norman JG, Kalbacher BJ, Jackels SC. J. Chem. Soc.-Chem. Commun. 1978:1027–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noodleman L, Norman JG, Osborne JH, Aizman A, Case DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:3418–3426. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dey A, Francis EJ, Adams MWW, Babini E, Takahashi Y, Fukuyama K, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. Science. 2007;318:1464–1468. doi: 10.1126/science.1147753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaser T, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:859–868. doi: 10.1021/ar990125c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon EI, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Dey A, Szilagyi RK. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005;249:97–129. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:1643–1645. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day MW, Hsu BT, Joshua-Tor L, Park JB, Zhou ZH, Adams MWW, Rees DC. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1494–1507. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dauter Z, Wilson KS, Sieker LC, Moulis JM, Meyer J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8836–8840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertini I, Luchinat C, Nerinovski K, Parigi G, Cross M, Xiao ZG, Wedd AG. Biophys. J. 2003;84:545–551. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74873-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao ZG, Lavery MJ, Ayhan M, Scrofani SDB, Wilce MCJ, Guss JM, Tregloan PA, George GN, Wedd AG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4135–4150. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao ZG, Gardner AR, Cross M, Maes EM, Czernuszewicz RS, Sola M, Wedd AG. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2001;6:638–649. doi: 10.1007/s007750100241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose K, Shadle SE, Eidsness MK, Kurtz DM, Jr, Scott RA, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10743–10747. [Google Scholar]

- 16.George GN. EXAFSPAK and EDG_FIT. Stanford, CA: Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Stanford University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenderholt AL. PySpline, Version 1.0. http://pyspline.sourceforge.net/

- 18.Shadle SE, Penner-Hahn JE, Schugar HJ, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:767–776. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedman B, Frank P, Gheller SF, Roe AL, Newton WE, Hodgson KO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:3798–3805. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 03, ReVision C02. Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becke AD. Phys. Rev. A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perdew JP. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;33:8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulliken RS. J. Chem. Phys. 1955;23:2338–2342. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulliken RS. J. Chem. Phys. 1955;23:2343–2346. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulliken RS. J. Chem. Phys. 1955;23:1833–1840. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulliken RS. J. Chem. Phys. 1955;23:1841–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ros P, Schuit GCA. Theor. Chim. Acta. 1966;4:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenderholt AL. PyMOlyze, Version 1.1. http://pymolyze.sourceforge.net.

- 29.Neese F, Olbrich G. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002;362:170–178. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neese F. ORCA – An Ab-initio, DFT and Semiempirical Electronic Structure Package, Version 2.6. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaser T, Rose K, Shadle SE, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:442–454. doi: 10.1021/ja002183v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anxolabéhère-Mallart E, Glaser T, Frank P, Aliverti A, Zanetti G, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5444–5452. doi: 10.1021/ja010472t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rose K, Shadle SE, Glaser T, de Vries S, Cherepanov A, Canters GW, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2353–2363. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarangi R, George SD, Rudd DJ, Szilagyi RK, Ribas X, Rovira C, Almeida M, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2316–2326. doi: 10.1021/ja0665949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Due to limited stability, the loading percentage of the metal center for C6S and C39S could only be estimated to be ~60% in C6S and ~50% in C39S using the pre-edge intensity.

- 36.Niu SQ, Ichiye T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5724–5725. doi: 10.1021/ja900406j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yachandra VK, Hare J, Moura I, Spiro TG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:6455–6461. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Czernuszewicz RS, Kilpatrick LK, Koch SA, Spiro TG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:7134–7141. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Czernuszewicz RS, Legall J, Moura I, Spiro TG. Inorg. Chem. 1986;25:696–700. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Note the Fe-S stretching frequency does not shift up upon lyophilization. When the donation increases upon lyophilization, the charge on Fe decreases and thus the ionic interaction between Fe and S becomes weaker and oppose the increase in covalent interaction41.

- 41.Gorelsky SI, Basumallick L, Vura-Weis J, Sarangi R, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Fujisawa K, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:4947–4960. doi: 10.1021/ic050371m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Fe-S-C-C diheral angles of the interior thiolates also differ from those of the surface thiolates (~180° vs. ~90°). However a geometry optimization of an Fe(SCH2CH3)4 model complex where two Fe-S-C-C diheral angles are 90° and the other two are 180° gives four identical Fe-S bond lengths (See Supporting Information).

- 43.Corrected from the atomic ionization energy using the NPA charge of the WT Rd model.

- 44.Ballhausen CJ, Gray HB. Molecular orbital theory: An introductory lecture note and reprint volume. W. A. Benjamin, Inc.; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calculated from DFT energies of the WT and C42S models with and without water.

-

46.The covalencies of the entire alkoxide and thiolate ligands for WT and C42S with and without water are listed in the table below. The change in thiolate ligand covalencies for WT and C42S upon solvation parallel the change in S covalencies discussed above, i.e. for WT the surface thiolates decrease in covalency while the interior ligands increase in covalency, giving a net covalency decrease; for C42S the surface thiolate decreases in covalency while the interior thiolates increase, giving a net covalency increase. The change in whole ligand covalencies in going from WT to C42S also parallel the change in S/O covalencies, i.e. alkoxide donates less than the thiolates but can reduce the thiolate donation.

Whole ligand CSPA Covalency Average (thiolate) C42 C9 C6 C39 WT 63.4 76.1 76 45.9 55.7 WT_2water 58.5 66.2 62.9 47.9 57.3 C42S 54.7 26.8 (O) 74 41.7 48.3 C42S_2water 56.6 24.5 (O) 70.3 46.5 53.0 - 47.This energy shift would not be observed in the experimental S K-edge data as the resolution is ~0.1 eV.

-

48.From our own calculations on a ferredoxin model Fe4S4SMe4 (see the table below), CSPA reproduced the experimental covalency decrease for both sulfide and thiolate upon solvation. MPA reproduced the experimental covalency decrease for the sulfide, but not for thiolate, because the Fe-S overlap increases for the sulfides but decreases for the thiolates, upon solvation.

Sulfide Covalency (%) Thiolate Covalency (%) Total covalency (%) Exp. MPA CSPA Exp. MPA CSPA Exp. MPA CSPA 4Fe Fd 468 418 416 152 132 141 617 550 557 4Fe Fd+8water 420 378 388 136 128 131 557 506 519 - 49.Dey A, Okamura T, Ueyama N, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12046–12053. doi: 10.1021/ja0519031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dey A, Roche CL, Walters MA, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:8349–8354. doi: 10.1021/ic050981m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stephens PJ, Jollie DR, Warshel A. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2491–2513. doi: 10.1021/cr950045w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gomes CM, Silva G, Oliveira S, LeGall J, Liu MY, Xavier AV, RodriguesPousada C, Teixeira M. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22502–22508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Achim C, Bominaar EL, Meyer J, Peterson J, Münck E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:3704–3714. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Achim C, Golinelli MP, Bominaar EL, Meyer J, Münck E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8168–8169. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crouse BR, Meyer J, Johnson MK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9612–9613. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.