Abstract

Background: A phase III trial demonstrated that cetuximab is the first agent in 30 years to improve survival when added to platinum-based chemotherapy (platinum-fluorouracil) first line for recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN). This analysis of the trial assessed the impact of treatment on quality of life (QoL).

Patients and methods: The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire-Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and QLQ-Head and Neck 35 (QLQ-H&N35) module were used to assess QoL.

Results: Of 442 patients randomly assigned, 291 (QLQ-C30) and 289 (QLQ-H&N35) patients completed at least one evaluable questionnaire. For QLQ-C30, cycle 3 and month 6 mean scores for platinum–fluorouracil plus cetuximab were not significantly worse than those for platinum–fluorouracil. Pattern-mixture analysis demonstrated a significant improvement in the global health status/QoL score in the cetuximab arm (P = 0.0415) but no treatment differences in the social functioning scale. For QLQ-H&N35, the mean score for the cetuximab arm was not significantly worse than that for the chemotherapy arm for all symptom scales at all post-baseline visits. At cycle 3, some symptom scores significantly favored the cetuximab arm (pain, swallowing, speech problems, and social eating).

Conclusion: Adding cetuximab to platinum–fluorouracil does not adversely affect the QoL of patients with recurrent and/or metastatic SCCHN.

Keywords: cetuximab, cisplatin, head and neck cancer, quality of life, recurrent and metastatic

introduction

For patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), platinum has been an integral part of palliative care for about the past 30 years. The median survival time of these patients remains around 6–7 months [1]. In 2008, the EXTREME (Erbitux in first-line treatment of recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer) trial (n = 442) demonstrated that adding the immunoglobulin G1 epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeting monoclonal antibody cetuximab to first-line platinum (cisplatin or carboplatin) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) significantly improved outcome compared with platinum-based chemotherapy alone for patients with recurrent and/or metastatic SCCHN [2]. Adding cetuximab to platinum-based chemotherapy significantly prolonged median overall survival [7.4 versus 10.1 months; hazard ratio (HR) for death 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.64–0.99; P = 0.04) and progression-free survival (PFS; 3.3 versus 5.6 months; HR for progression 0.54, 95% CI 0.43–0.67; P < 0.001) and significantly increased the response rate from 20% to 36% (P < 0.001) [2]. This is the first randomized trial in 30 years to show a benefit of adding a new drug to platinum-based therapy over platinum-based chemotherapy alone.

Cetuximab is generally well tolerated in SCCHN [2–6], the most common adverse event being skin reactions. In the EXTREME trial, the incidence of grade 3/4 events was similar between the treatment arms, with the exception of skin reactions (9% versus <1%; P < 0.001), sepsis (4% versus <1%; P = 0.02), and hypomagnesemia (5% versus 1%; P = 0.05), which were higher in the combined chemotherapy–cetuximab arm [2]. The use of cetuximab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer [7–9] or when added to radiotherapy for patients with locally advanced SCCHN [10] appears not to adversely affect patients’ quality of life (QoL). A secondary objective of the EXTREME trial was to compare the QoL of patients receiving platinum–fluorouracil plus cetuximab with that of patients receiving platinum–fluorouracil alone for recurrent and/or metastatic SCCHN.

patients and methods

study design and treatment

The methods and results for the phase III EXTREME trial have previously been described [2]. The protocol was approved by the independent ethics committees of each participating center and by the authorities in each country and the trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided oral and written informed consent.

Patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed recurrent and/or metastatic SCCHN (excluding nasopharyngeal carcinoma) not suitable for local therapy and a Karnofsky performance score (KPS) of ≥70 were randomly assigned to receive cisplatin (100 mg/m2 as a 1-h i.v. infusion on day 1) or carboplatin [AUC (area under the curve for drug concentration as a function of time) 5 mg·min/ml by 1-h i.v. infusion on day 1] and an infusion of 5-FU (1000 mg/m2 per day for 4 days) every 3 weeks, with or without cetuximab [initial dose of 400 mg/m2 (2-h i.v. infusion) followed by subsequent weekly doses of 250 mg/m2 (1-h i.v. infusion), ending at least 1 h before the start of chemotherapy] [2]. Treatment was continued for a maximum of six cycles of chemotherapy. After six cycles, patients in the cetuximab arm who had at least stable disease received cetuximab monotherapy until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, whereas patients in the chemotherapy-alone arm received no further active treatment but remained in the study until disease progression. Randomization was stratified according to receipt or nonreceipt of previous chemotherapy and KPS (<80 versus ≥80).

The primary objective of the trial was to assess the effects of treatment on overall survival. QoL was a secondary objective.

QoL analysis

Two European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) multidimensional QoL questionnaires were used [11, 12].

The QoL Questionnaire-Core 30 (QLQ-C30 version 3.0) is a cancer-specific, self-administered questionnaire with 30 questions and comprises an overall global health status/QoL scale; five functional scales—physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning scales; three multi-item symptom scales—fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and pain; and six single-item symptom scales—dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties.

The QLQ-Head and Neck 35 (QLQ-H&N35) module is a head and neck cancer-specific module with 35 questions and comprises 7 multi-item symptom scales—pain, problems with swallowing, sense, speech, social eating, social contact, and reduced sexuality—and 11 single-item symptom scales—problems with teeth, opening the mouth, dry mouth, sticky saliva, coughing, feeling ill, requirement for analgesics, nutritional supplements, use of a feeding tube, weight loss, and weight gain.

QoL assessments were conducted at each study site where appropriate validated translations of the instruments were available. The scores of the scales were calculated according to the procedure defined in the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual [11]. All the scores were derived from mutually exclusive sets of items, with scale scores ranging from 0 to 100 after a linear transformation. For the global health status/QoL and functioning scales, higher scores indicate higher levels of function and QoL. For symptom scales, higher scores indicate worse symptoms or QoL. The prognostic value of the baseline global health status/QoL, fatigue and physical functioning scale scores were investigated to analyze their relationship with overall survival.

schedule of assessments

Patients were scheduled to complete the questionnaires at screening or baseline, on day 1 of cycle 3, at the first 6-weekly evaluation following completion of chemotherapy, at 6 and 12 months after randomization, and at the final tumor assessment (supplemental Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Only questionnaires with a date of assessment and completed within the cut-off date and before further antitumor therapy were considered evaluable. Only one questionnaire per patient per time window was analyzed. If a patient completed multiple questionnaires within a time window, the one completed closest to the scheduled assessment was analyzed.

statistical analysis

The null hypothesis to be tested with regard to treatment effect was that there was no difference between the treatment groups. All statistical tests were performed two sided at the 5% level. No adjustments for multiple testing were made.

Compliance was defined for each assessment period as the ratio of the total number of patients with at least one evaluable questionnaire over the total number of patients for whom a questionnaire was expected.

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population comprised all patients randomly assigned from countries where the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35 questionnaires were available. Baseline characteristics were summarized for patients with at least one evaluable questionnaire for the relevant instrument. Descriptive statistics were provided for continuous and categorical variables. A logistic regression model was fitted to test if the dropout process was missing completely at random. The P value for the Wald chi-square test was used to test the effect of QoL scores on drop out. QoL data were analyzed using descriptive statistics for the multi-item and single-item measures for each treatment group at each of the assessments points. Least-squares (LS) mean estimates for a treatment by time interaction, and the difference in the LS means and associated P values, were obtained from an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model (including terms for age, gender, histology, KPS, disease stage, EGFR staining, and a treatment by time interaction) fitted for time points where at least 20% of patients completing a baseline QoL questionnaire remained in the population. Results were presented as adjusted and not adjusted for differences at baseline. Plots of the QoL scores over time were generated for the global health status/QoL and social functioning scales. Exploratory analyses assessed per patient best (functioning and generic scales) and worst (functioning, generic, and symptom scales) QoL summary scores, and the change between baseline and best and worst scores for each scale, and compared between treatment arms using the Wilcoxon nonparametric test.

The primary QoL analysis was a pattern-mixture analysis of the mean global health status/QoL scores and social functioning scores against time by dropout pattern for each treatment group. Only time points where at least 20% of patients completing a baseline QoL questionnaire remained in the population were included in the analysis. For prognostic factor analysis, baseline global health status/QoL, fatigue, and physical functioning scale scores were split at the median to yield ‘good’ and ‘poor’ scores. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier technique. The Cox proportional hazards regression model, stratified for treatment arm, was used for multivariate analyses. Significance was assessed using the Wald chi-square test, the HR and its 95% CI values.

results

QoL assessments

A total of 442 patients were randomly assigned to receive treatment in the EXTREME trial, 220 to platinum–fluorouracil and 222 to platinum–fluorouracil plus cetuximab. The ITT subset populations for the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35 questionnaires comprised 361 patients. No QoL assessments were conducted in Hungary (n = 43), Ukraine (n = 34), or Slovakia (n = 4) due to the lack of validated questionnaire translations.

Results are presented for the assessments at cycle 3 and at 6 months. In general, the numbers of patients contributing data at the first 6-weekly evaluation visit after the end of chemotherapy, at 12 months, and at the final tumor assessment were insufficient to allow meaningful statistical analysis.

evaluability and compliance

Altogether, ∼80% of the ITT subset completed at least one evaluable questionnaire: 291 patients for the QLQ-C30 questionnaire (152 receiving platinum–fluorouracil plus cetuximab and 139 receiving platinum–fluorouracil alone) and 289 for the QLQ-H&N35 module (152 and 137 patients, respectively). Of 812 QLQ-C30 and 799 QLQ-H&N35 questionnaires completed, ∼60% were evaluable.

Compliance rates for both questionnaires were ≤55% in both treatment arms at all scheduled post-baseline assessments. The slightly higher compliance rates seen in the combined treatment arm can be explained partly by the higher dropout rate in the chemotherapy-alone arm. For both questionnaires, only 44% of patients had both an evaluable baseline and a post-baseline assessment.

The baseline demographics of patients completing at least one QLQ-C30 questionnaire (Table 1) or QLQ-H&N35 module were generally similar between treatment arms, with the exceptions that there were more women and slightly fewer cases of stage IV disease in the cetuximab arm. Among patients not evaluable for the QoL analysis, there were no marked differences between the treatment arms in the extent of disease, the stage of the disease, or the KPS. The baseline demographics of the QoL population were broadly similar to those in the ITT population of the EXTREME trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for patients completing evaluable EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaires

| Characteristic | Platinum–fluorouracil + cetuximab (n = 152) | Platinum–fluorouracil alone (n = 139) |

| Male, n (%) | 131 (86) | 130 (94) |

| Female, n (%) | 21 (14) | 9 (6) |

| Median age, years (range) | 56 (37–80) | 56 (33–78) |

| Karnofsky performance score, n (%) | ||

| <80 | 20 (13) | 20 (14) |

| ≥80 | 132 (87) | 119 (86) |

| Extent of disease, n (%) | ||

| Only locoregionally recurrent | 76 (50) | 70 (50) |

| Metastatic with or without locoregional recurrence | 76 (50) | 69 (50) |

| Histology, n (%) | ||

| Well/moderately differentiated | 94 (62) | 89 (64) |

| Poorly differentiated | 28 (18) | 30 (22) |

| Not specified | 28 (18) | 19 (14) |

| Missing | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Disease stage, n (%) | ||

| I–III | 57 (38) | 42 (30) |

| IV | 92 (61) | 91 (65) |

| Missing | 3 (2) | 6 (4) |

| % EGFR staining, n (%) | ||

| <40 | 21 (14) | 21 (15) |

| ≥40 | 123 (81) | 107 (77) |

| Missing | 8 (5) | 11 (8) |

| Platinum therapy, n (%) | ||

| Cisplatin | 96 (63) | 86 (62) |

| Carboplatin | 55 (36) | 51 (37) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30.

QLQ-C30 analysis

At cycle 3 and at 6 months, for each of the functioning and symptom scales, the mean scores in the cetuximab-containing arm were generally favorable and were not significantly worse than those in the chemotherapy-alone arm.

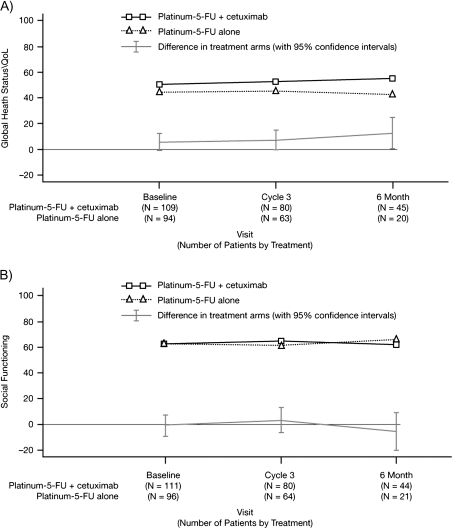

At the 6-month assessment, the LS mean for global health status/QoL was significantly higher in the cetuximab-containing arm compared with the chemotherapy-alone arm (difference in LS means 12.81 points; P = 0.0399). However, the difference was not statistically significant when the scores were adjusted for baseline (7.22 points, P = 0.2842). At cycle 3, differences in the LS means for the physical functioning scale and the three multi-item symptom scales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and pain) were all significantly in favor of cetuximab-containing arm (Table 2). However, statistical significance was not retained when scores were adjusted for baseline. Figure 1 shows the LS means for global health status/QoL and social functioning scores over time from baseline to month 6. The mean worst post-baseline scores for global health status/QoL and the five functional scales were not significantly different between the treatment arms. The mean best post-baseline scores consistently favored the cetuximab-containing arm, although between-arm differences did not reach statistical significance. For the multi-item symptom scales of fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and pain, there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment arms in the mean worst post-baseline scores or in the mean change from baseline to worst post-baseline symptom scores. For the six single-item symptom scales, there were no statistically significant differences in the mean change from baseline to worst post-baseline scores between treatment groups for any item.

Table 2.

EORTC QLQ-C30 scores between treatment arms at the cycle 3 assessment for the physical functioning scale and the multi-item symptoms scale

| QLQ-C30 scale | Statistic | Platinum–fluorouracil + cetuximab (n = 152) | Platinum–fluorouracil alone (n = 139) | Difference in LS means (95% CI) | P value | Difference in LS means adjusted for baseline (95% CI) | P value |

| Functioning scalesa | |||||||

| Physical functioning | LS mean score (n)b | 67.46 (79) | 59.72 (64) | 7.74 (0.69 to 14.79) | 0.0317 | 1.23 (−6.26 to 8.72) | 0.7458 |

| Multi-item symptom scale | |||||||

| Fatigue | LS mean score (n)b | 48.12 (80) | 58.70 (64) | −10.58 (−19.24 to −1.92) | 0.0169 | −5.54 (−15.11 to 4.03) | 0.2547 |

| Nausea and vomiting | LS mean score (n)b | 19.99 (79) | 26.66 (64) | −6.67 (−13.27 to −0.06) | 0.0478 | −6.49 (−14.15 to 1.18) | 0.0965 |

| Pain | LS mean score (n)b | 22.93 (80) | 35.72 (64) | −12.79 (−22.35 to −3.24) | 0.0090 | −10.35 (−20.99 to 0.29) | 0.0566 |

There were no statistically significant differences between the treatment arms in the outcomes for the other functioning scales: role, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning scales. Note that higher scores for physical functioning indicate better physical functioning, whereas higher scores for symptoms indicate worse symptoms.

Patients without missing covariates in the multivariate mixed model.

CI, confidence interval; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30; LS, least squares.

Figure 1.

(A) EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status/quality of life and (B) social functioning scores over time from baseline to month 6 by treatment arm (least-squares means). EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30.

Pattern-mixture analysis revealed a significant difference in the global health status/QoL score between treatment groups in favor of the cetuximab-containing arm (P = 0.0415). There was no statistically significant difference between the treatment arms in the social functioning scale.

QLQ-H&N35 analysis

At cycle 3 and at month 6, for every symptom scale, the mean score in the cetuximab-containing arm was not significantly worse than that in the platinum–5-FU-alone arm.

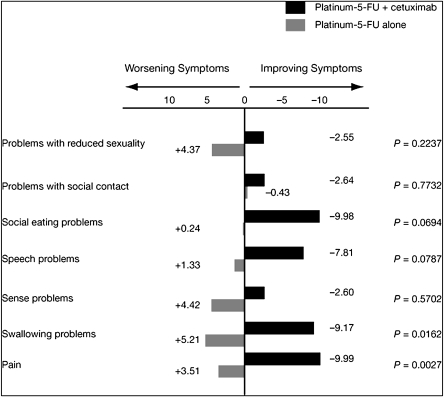

At cycle 3, differences between the arms in the LS means for four of the seven multi-item symptom scales (pain and problems with swallowing, speech, and social eating) were significantly in favor of the cetuximab-containing arm. These differences remained significant after adjusting for the difference at baseline (Table 3). There were no significant differences between the treatment arms in the mean worst post-baseline scores for any of the seven multi-item symptom scales (pain or problems with swallowing, sense, speech, social eating, social contact, or reduced sexuality). However, there were statistically significant differences in the mean change from baseline to worst post-baseline scores for pain in favor of platinum–fluorouracil plus cetuximab (Figure 2). Between-group differences in favor of the cetuximab group in speech problems and trouble with social eating were of borderline significance.

Table 3.

EORTC QLQ-H&N35 multi-item symptom scale scores at the cycle 3 assessment

| QLQ-H&N35 scale | Statistic | Platinum–fluorouracil + cetuximab (n = 152) | Platinum–fluorouracil alone (n = 137) | Difference in LS means (95% CI) | P value | Difference in LS means adjusted for baseline (95% CI) | P value |

| Pain | LS mean score (n)a | 25.79 (80) | 37.68 (63) | −11.89 (−19.79 to −3.99) | 0.0034 | −11.91 (−20.70 to −3.11) | 0.0083 |

| Swallowing problems | LS mean score (n)a | 36.88 (79) | 51.01 (60) | −14.12 (−23.54 to −4.71) | 0.0035 | −14.44 (−24.03 to −4.84) | 0.0034 |

| Speech problems | LS mean score (n)a | 39.15 (78) | 51.11 (59) | −11.96 (−21.16 to −2.76) | 0.0112 | −14.07 (−23.25 to −4.89) | 0.0029 |

| Social eating problems | LS mean score (n)a | 40.31 (79) | 50.89 (57) | −10.58 (−20.60 to −0.57) | 0.0384 | −11.86 (−21.67 to −2.04) | 0.0182 |

There were no statistically significant differences between the treatment arms in the outcomes for the other items on the multi-item symptom scale: sense, social contact, and sexuality. Note that higher scores for symptom scales indicate worse symptoms.

Patients without missing covariates in the multivariate mixed model.

CI, confidence interval; EORTC QLQ-H&N35, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Head and Neck 35; LS, least squares.

Figure 2.

EORTC QLQ-H&N35 multi-item symptom scale scores: mean change from baseline to worst post-baseline scores. EORTC QLQ-H&N35, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Head and Neck 35.

For the 11 single-item symptom scales, the only significant difference in the worst post-baseline score between the treatment arms was for cough: e.g. more than half (55%) of the patients in the cetuximab-containing arm showed little or no post-baseline cough compared with 34% receiving platinum–fluorouracil alone (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences in the mean change from baseline to worst post-baseline scores between treatment groups for any item when figures were adjusted for baseline.

Table 4.

EORTC QLQ-H&N35 worst post-baseline single-item symptom scale scores for selected symptoms

| Symptom | Extent of problem, n (%) |

|||

| Platinum–fluorouracil + cetuximab (n = 152) |

Platinum–fluorouracil alone (n = 137) |

|||

| None at all/a little | Quite a bit/very much | None at all/a little | Quite a bit/very much | |

| Problems with teeth | 83 (55) | 16 (11) | 61 (45) | 11 (8) |

| Problems with opening mouth | 68 (45) | 33 (22) | 48 (35) | 27 (20) |

| Dry mouth | 58 (38) | 44 (29) | 46 (34) | 30 (22) |

| Sticky saliva | 50 (33) | 50 (33) | 35 (26) | 40 (29) |

| Coughing | 83 (55) | 19 (13) | 46 (34) | 28 (20) |

| Feeling ill | 74 (49) | 28 (18) | 50 (36) | 25 (18) |

EORTC QLQ-H&N35, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Head and Neck 35.

prognostic value of QoL

Patients with a higher global health status/QoL score at baseline had a lower risk of death than those with a lower score at baseline (HR 1.87, 95% CI 1.38–2.53; P < 0.0001). In multivariate analysis, the baseline factors significantly associated with a poorer survival were KPS <80 (HR 1.98, 95% CI 1.28–3.04; P = 0.0019), poorly differentiated histology (HR 1.61, 95% CI 1.01–2.56; P = 0.0432), and poor global health status (HR 1.58, 95% CI 1.05–2.39; P = 0.0287).

missing data patterns

Of the 291 patients with evaluable QLQ-C30 questionnaires, missing data patterns were intermittent for 80 and monotone (a complete series of questionnaires before drop out) for 211. For intermittent missing data, the primary reason documented at all time points was a random occurrence, unrelated to the QoL of the patients. For monotone missing data, logistic regression analysis revealed a nonrandom pattern whereby patients with a low previous global health status/QoL score had a higher probability of drop out. The dropout rate was not statistically significantly different between the treatment arms. This effect was confirmed by pattern-mixture analysis, which showed that patients in both arms of the study remaining in the study longer had a better global health status/QoL score at baseline.

discussion

The results of this analysis demonstrate that adding cetuximab to platinum–fluorouracil does not negatively affect the QoL of patients with recurrent and/or metastatic SCCHN.

In general, QLQ-C30 summary QoL measures showed a favorable mean score for platinum–fluorouracil plus cetuximab and none of the scales showed a significantly worse score for this combination. Longitudinal analyses revealed some between-arm differences in favor of the combined treatment with cetuximab at some individual time points for global health status, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and pain, but differences were not statistically significant when adjusted for baseline. Simplified analyses, which do not take the dropout pattern into account, can be subject to bias. In this analysis, the evaluability rates were rather low, ∼60%. Compliance rates were also rather low, with a post-baseline compliance rate of at most 55%. These figures probably reflect the fact that collection of QoL data was not compulsory in the phase III trial. The rates of questionnaire evaluability and compliance were both better in the cetuximab-containing arm than in the chemotherapy-alone arm. In addition, the dropout rate was higher for chemotherapy alone. According to logistic regression and pattern-mixture analyses, the probability of drop out was dependent on the previous global health status/QoL score: if these were low, then the probability of drop out was high.

When the dropout pattern was taken into account, adding cetuximab to platinum–fluorouracil was associated with a statistically significant improvement in patients’ overall global health status/QoL score (P = 0.0415), compared with platinum–fluorouracil alone. A similar analysis of the QLQ-C30 social functioning scale revealed no statistically significant difference between the treatment arms, suggesting that the addition of cetuximab to platinum–fluorouracil did not have a negative effect on patients’ ability to function normally in a social context [10].

The results from the QLQ-H&N35 module also generally favored the combined use of platinum–fluorouracil and cetuximab. At cycle 3, statistically significant differences in favor of the cetuximab arm for pain and problems with swallowing, speech, and social eating were observed. The results for pain and problems with swallowing were confirmed by the changes from baseline to worst post-baseline score. These results provide evidence to suggest that adding cetuximab to platinum–fluorouracil helps to alleviate the symptoms associated with head and neck cancer.

The applicability and validity of version 3.0 of the QLQ-C30 questionnaire [12] and the QLQ-H&N35 module [12, 13] for assessing QoL in patients with head and neck cancer from a range of countries has been demonstrated. These instruments were also used to investigate QoL in patients receiving cetuximab plus radiotherapy for locally advanced SCCHN [10], and the results from that analysis are similar to those reported here, with no adverse effects on global health status/QoL or social functioning as a result of adding cetuximab to a standard treatment approach.

In the current analysis, baseline global health status/QoL was identified as a statistically significant prognostic indicator. This finding supports those of other large analyses of patients with early- and late-stage head and neck cancers [14, 15] and is consistent with the finding of Curran et al.’s [10] analysis of cetuximab in locoregionally advanced disease.

In conclusion, this analysis supports the clinical benefits of adding a third agent (cetuximab) to first-line platinum-based doublet therapy (i.e. cisplatin or carboplatin in combination with infusional 5-FU) in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic SCCHN. Not only does cetuximab plus platinum-based therapy provide statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in overall survival, PFS, and response and disease control rates compared with platinum-based chemotherapy alone [2], it does this without adversely affecting QoL. Moreover, adding cetuximab to this type of platinum-based chemotherapy provided relief from some of the symptoms associated with SCCHN. These findings strongly support the place of cetuximab plus platinum–fluorouracil as a new standard first-line therapy for recurrent and/or metastatic SCCHN.

funding

Merck KGaA.

disclosures

DCur reports being a consultant statistician and QoL expert; AG is an employee of Merck KGaA; RM reports receiving lecture fees from Merck KGaA and sanofi-aventis; FR reports serving on advisory boards and receiving research grants from Merck KGaA; SR reports receiving lecture fees from Merck KGaA; JBV reports serving on paid advisory boards of Merck KGaA, Amgen, and Oncolytics Biotech Inc., and receiving lecture fees from Merck KGaA, Amgen, Lilly, and Boehringer-Ingelheim; and MB, CB, DCup, J-PD, DDR, RH, HK, and PK declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Oliver Kisker for his clinical input and critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Schantz SP, Harrison LB, Forastiere A. Tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, oral cavity, and oropharynx. In: DeVita VT, Hellman SA, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer. Principles and Practice of Oncology. 6th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 797–860. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermorken JB, Trigo J, Hitt R, et al. Open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck who failed to respond to platinum-based therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2171–2177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burtness B, Goldwasser MA, Flood W, et al. Phase III randomized trial of cisplatin plus placebo compared with cisplatin plus cetuximab in metastatic/recurrent head and neck cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8646–8654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourhis J, Rivera F, Mesia R, et al. Phase I/II study of cetuximab in combination with cisplatin or carboplatin and fluorouracil in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2866–2872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Au H-J, Karapetis CS, O'Callaghan CJ, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab: overall and KRAS-specific results of the NCIC CTG and AGITG CO.17 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1822–1828. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folprecht F, Nowacki M, Lang I, et al. Cetuximab plus FOLFIRI first line in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): a quality-of-life (QoL) analysis of the CRYSTAL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. (Abstr 4076) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobrero AF, Maurel J, Fehrenbacher L, et al. EPIC: phase III trial of cetuximab plus irinotecan after fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2311–2319. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curran D, Giralt J, Harari PM, et al. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients after treatment with high-dose radiotherapy alone or in combination with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2191–2197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. Brussels, Belgium: EORTC; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers PM, et al. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. EORTC Quality of Life Group. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1796–1807. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman AC, Simonton S, Adams DC, et al. Assessing quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer: cross-validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Head and Neck module (QLQ-H&N35) Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:459–467. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grignon LM, Jameson MJ, Karnell LH, et al. General health measures and long-term survival in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:471–476. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Ronis DL, Fowler KE, et al. Quality of life scores predict survival among patients with head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2754–2760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.