Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is defined as the presence of a hypertrophied, non-dilated ventricle in the absence of another disease that creates a hemodynamic disturbance that is capable of producing the existent magnitude of wall thickening (eg, hypertension, aortic valve stenosis, catecholamine secreting tumors, hyperthyroidism, etc). HCM accounts for 42% of childhood cardiomyopathy and has an incidence of 0.47/100,000 children 1 and represents a heterogeneous group of disorders with a diversity that is more apparent in childhood than at any other age. It is possible to further subdivide these diseases based on a number of characteristics. A classification is presented in List 1 based on groupings of familial, syndromic, neuromuscular, and metabolic (storage disease and mitochondrial disorders). Other classification schemes are commonly used, including division into primary and secondary forms, where the primary form is a familial disorder (“familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy”, FHC) typically devoid of findings outside of the heart, and the secondary forms include diseases such as Friedreich ataxia 2 where ventricular hypertrophy is common but is not the dominant clinical manifestation and others, such as glycogenosis Type IX 3, in which a systemic disorder has primarily or exclusively cardiac manifestations.

List 1.

Phenotypically-based classification of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

| Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy |

| Sarcomeric Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy |

| Maternally-Inherited Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Syndromes |

| Syndromic Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy |

| Noonan’s Syndrome |

| Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome |

| Cardio-facial-cutaneous syndrome |

| Costello syndrome |

| Lentiginosis (LEOPARD Syndrome) |

| Neuromuscular disease |

| Friedreich’s Ataxia |

| Metabolic Disorders |

| Anabolic steroid therapy and abuse |

| Carnitine deficiency (Carnitine palmitoyl transferase II deficiency, carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase deficiency) |

| Fucosidosis type 1 |

| Glycogenoses type 2, 3 and 9 (Pompe’s disease, Forbes’ disease, Phosphorylase kinase deficiency) |

| Glycolipid lipidosis (Fabry Disease) |

| Glycosylation disorders |

| I-Cell disease |

| Infant of diabetic mother |

| Lipodystrophy, total |

| Lysosomal disorders (Danon’s Disease) |

| Mannosidosis |

| Mitochondrial disorders (multiple forms) |

| Mucopolysaccharidoses type 1, 2 and 5 (Hurler’s syndrome, Hunter’s syndrome, Scheie’s syndrome) |

| Pre and postnatal Corticosteroid therapy |

| Selenium deficiency |

Most of the available information for HCM derives from studies in adult populations, and the implication of these observations for pediatric populations is often uncertain. The purpose of this review is not to attempt to review the vast body of literature that has accumulated about HCM but rather to summarize key findings and to discuss their implications for diagnosis and management of children with HCM.

Epidemiology and Survival

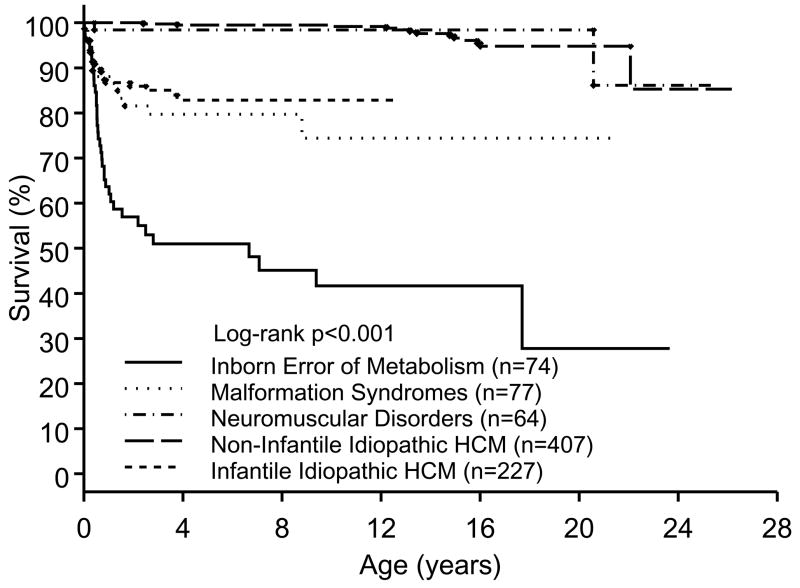

The Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry is a multicenter observational study of pediatric cardiomyopathies initiated in 1995 that in 2003 reported the sex, age, and race-specific incidence of the several forms of cardiomyopathy based on 2 geographically diverse sections of the United States 1. Of note, the incidence of HCM was found to be 69% more common in males, occurred at 10 times the rate in subjects under age 1, and was significantly more common in blacks than in whites or Hispanics. Subsequently, the distribution of etiologies and the etiology-specific survival in 849 children, the largest series to date, was reported 4. Overall, there was nearly equal distribution between inborn errors of metabolism (IEM, 9%), malformation syndromes (MFS, 9%), and neuromuscular disorders (NMD, 8%), with the remaining 75% represented by the idiopathic and FHC patients. The mean age at diagnosis was under 6 months in the IEM and MFS groups whereas the other groups were typically older at the time of diagnosis. Survival was found to be etiology- and age-specific confirming that survival in infants is much poorer than in older groups but documenting that this can be attributed to the high incidence of IEM and NMD at this age whereas the survival for patients with NMD and FHC was similar regardless of age at diagnosis (Figure 1). A notable observation was that annual mortality in children with FHC was 1.1 per 100 patient-years, which compares favorably with contemporary reports in adults with FHC. This finding contrasted to earlier and smaller series in children that reported much higher annual mortality.

Figure 1.

Percent survival as a function of age in children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) due to various classes of etiology.

Infantile Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

The infant with HCM represents a particularly difficult challenge with regard to determining an etiologic diagnosis due to the wide range of disorders for which an association has been reported (List 1). Successful determination of a specific diagnosis is likely to have significant impact on management and survival because of the differences in etiology-specific survival. Although the pace of advances in genetic and metabolic diagnostics has quickened and the chances that a specific diagnosis can be achieved has improved substantially in recent years, about 50% of HCM cases under age 1 remain idiopathic 4. Amongst those patients for whom a defined etiology is identified, a few disorders (Pompe disease, Noonan syndrome, and FHC) account for the largest percent and etiologic diagnosis in the remainder is far more difficult. From the cardiac perspective, the association of particular patterns of the cardiac phenotype with specific etiologies has been an area of considerable interest because of the potential to guide the evaluation. For example, the finding of a hypertrophic, hypokinetic left ventricle has been most frequently associated with IEM, and in particular with mitochondrial defects. Biventricular outflow tract obstruction is more common in Noonan syndrome than in other forms of infantile HCM. Asymmetric patterns of hypertrophy are more commonly seen in syndromic and familial HCM than in IEM. Although these sorts of observations can provide some guidance, for most infants with HCM early referral for multi-specialty evaluation including specialists in cardiology, neurology, genetics, and metabolism is warranted.

Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Genetics

The genetic transmission of FHC is usually autosomal dominant, with a significant percentage of cases representing apparently new mutations. Maternally inherited mitochondrial pattern of transmission has also been reported 5, adding to the complexity of the disease. There has been a virtual explosion of information since the early 1990’s concerning the genetic abnormalities associated with this disorder. One of the most striking findings has been the sheer number of diverse mutations that manifest clinically as HCM. The results of molecular studies so far have implicated a number of sarcomeric proteins in the etiology, including beta-myosin heavy chain, alpha-myosin heavy chain, myosin essential light chain, myosin regulatory light chain, cardiac troponin T, cardiac troponin I, alpha-tropomyosin, and myosin binding protein C, titin, and actin 6. These gene mutations display allelic heterogeneity; that is, multiple distinct mutations of each of these genes can cause the disease. The frequent finding of mutations in the sarcomeric proteins resulted in the paradigm of FHC as a disease of the sarcomere 7, an understanding that has been disrupted by the more recent identification of mutations in genes encoding non-sarcomeric proteins within the z-disc and calcium handling control mechanisms that result in a similar phenotype 6. There are also familial forms of HCM due to non-sarcomeric genes, such as those due to mitochondrial defects, potassium channel 8, and the gamma subunit of protein kinase A 9. Although sarcomeric defects appear to be the most common cause of FHC, they are not the only cause. Furthermore, at present the genotype responsible for the HCM phenotype cannot be determined in 30–40% of patients.

Commercially available genetic testing for some of the more common mutations causing FHC is a relatively recent event and one that has stimulated considerable discussion concerning who should have this testing performed. Although certain mutations may imply greater or lesser risk, the expectation that genotyping would markedly improve risk stratification and clinical management has been largely undercut by recent data 10. For example, mutations in troponin T were initially reported to have a consistent phenotype of mild or absent hypertrophy associated with a high incidence of sudden death 11, but families have been described with troponin T defects who have a low risk of early death 12. Other factors, such as the coexistence of mitochondrial DNA mutations in some families 13, multiple mutations 14, or the impact of coexistent genetic polymorphisms within the renin-angiotensin system 15 account for some of the variability in disease expression. It has been argued that detection of gene carriers in FHC may have too little impact on clinical care to justify the cost and the potential for adverse psychological and social consequences 16.

Implications for pediatrics

For infants, children, and young adults there are several benefits that are not considered in the foregoing analysis. One of the most feared complications of HCM in children and young adults is diagnosis of the disease at the time of sudden death. The potential to avert such events rests on diagnosis of the disease in asymptomatic children. Because development of the phenotype can be noted throughout childhood, current practice is to periodically screen offspring of affected individuals throughout childhood. Identification of a familial gene allows children who are genotype negative to avoid longitudinal evaluation for development of hypertrophy, markedly reducing the overall cost of care, in addition to anxiety reduction and elimination of concerns about exercise participation. Those children who carry the gene can be followed more closely for development of disease and they also become eligible for trials of interventions to prevent development of the phenotype. The potential to prevent the onset of hypertrophy remains an unproven hypothesis in humans although a mouse model of myosin heavy chain HCM treated prior to the onset of hypertrophy with diltiazem had less hypertrophy, fibrosis, and myocyte disarray than placebo-treated mice 17, and a clinical trial in phenotype negative, genotype positive children and young adults is currently in progress.

The phenomenon of incomplete penetrance (a negative phenotype in genotype positive adult members of a pedigree) has been well described in familial HCM and appears more common than has been previously believed. One of the implications of this finding is that all children in the pedigree, even offspring of phenotype negative parents, must be considered at risk and should undergo longitudinal evaluation for development of the phenotype unless the parents can be shown to be genotype negative. As a corollary, adult members of the pedigree who are found to carry the gene can be advised that they are at risk for transmitting the gene even if they are phenotypically negative. Finally, identification of the gene permits use of the relatively new technique of embryo pre-selection to allow carriers of the gene to avoid transmission to their offspring.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of HCM in infants is generally made during evaluation for a murmur or for congestive heart failure. Older children are diagnosed during investigations for murmurs, symptoms (impaired exercise capacity, chest pain, palpitations, or syncope), electrocardiographic abnormalities, and screening of offspring of affected adults. The echocardiogram provides definitive noninvasive assessment of ventricular size, wall thickness, systolic and diastolic function, outflow obstruction, and valvar insufficiency in nearly all children. Diagnosis has typically been based on increased regional or global wall thickness and excess regional variation in thickness. The usual adult criteria for diagnosis are based on an absolute wall thickness above the normal range (>12 mm), resulting in a significant false positive rate. Improved longitudinal observations and the advent of more widespread genotyping have improved the ability to refine these echocardiographic criteria. This issue is of particular importance in distinguishing physiologic from pathologic hypertrophies. Cardiac hypertrophy associated with intense athletic participation is well described in both children and young adults 18. In athletic subjects with mild hypertrophy on echocardiography, findings that increase the probability of HCM include unusual patterns of hypertrophy, small left ventricular cavity size, abnormal diastolic function indices, female gender, family history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and evidence of delayed enhancement with gadolinium on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) 19. Findings that increase the probability of physiologic hypertrophy include left ventricular cavity size near or above the upper limits of normal and elevated peak oxygen consumption on exercise testing. The electrocardiogram is not helpful in making this distinction. Ultimately, if reasonable certainty is not achieved based on these additional criteria, cessation of exercise participation for 6 months can be used to identify subjects with HCM, who will not experience a decrement in wall thickness. Unfortunately, obtaining adequate compliance with this recommendation is challenging in most athletes.

Implications for pediatrics

Use of age and body surface area adjusted normal values is necessary in children. The use of z-scores (defined as the number of standard deviations from the population mean) has been particularly helpful in this regard 20. The sensitivity and specificity for specific z-score values relative to diagnosis of HCM in children has not been tested, although in general the range of uncertainty between physiologic and pathologic hypertrophy corresponds to a z-score between 2 and 3, with physiologic hypertrophy rarely resulting in a wall thickness relative to body surface area that is more than 3 standard deviations above the population mean. Studies performed in genotypically positive children have identified a number of echocardiographic and electrocardiographic findings that can be abnormal despite the absence of hypertrophy 21–23. In particular, abnormal noninvasive diastolic function indices such as reduced early diastolic tissue velocities, prolonged isovolumic relaxation times, and increased left atrial volume have been described 23;24. These findings have important implications concerning the pathophysiology of the disease but the implications concerning diagnosis are more ambiguous. In children with mild hypertrophy, abnormal diastolic function indices make it highly likely that the hypertrophy is not physiologic. However, in the absence of hypertrophy, genotypically positive individuals do not meet the definition of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, are not known to be at increased risk for sudden death, and do not manifest symptoms. Furthermore, it is unclear whether all genotype positive, phenotype negative individuals will manifest hypertrophy over time. Although the term “hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without hypertrophy” has been used, the implication that disease status should be based on genetic status rather than phenotype remains unclear. This uncertainty is apparent in the conflicting exercise guidelines issued by the 36th Bethesda Conference and the European Society of Cardiology recommendations for sports participation, with the European but not the American group recommending against participation in phenotypically negative, genotypically positive individuals 25.

Management of symptoms

The goals of therapy in this disorder are to reduce symptoms and prolong survival. The symptoms of chest pain, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance can often be managed medically, and surgery has been successful in certain patient groups. Digitalis is not helpful and is usually contraindicated unless atrial fibrillation occurs. Although dyspnea is a common symptom, diuretic therapy is usually not beneficial, can increase the outflow gradient due to a reduction in chamber volume, and can reduce cardiac output. Outflow tract obstruction plays an important role with regard to symptom status in HCM. The clinical importance of outflow obstruction has been highly controversial over the years, as recently recounted in some detail by Maron 26. Patients with outflow tract obstruction are at greater risk for symptoms and progression to heart failure and death 27, and exercise-induced or exacerbated outflow tract obstruction is both common and associated with a higher risk of symptoms 28. Reduction in outflow tract obstruction is one of the primary targets of therapy for symptomatic patients. The gradient can be at detected rest or only with provocation such as inotropic stimulation, vasodilation, or exercise and often demonstrates marked spontaneous lability 29. Although provocation of latent outflow obstruction with maneuvers such as amyl nitrate has been recommended, the clinical significance of gradients elicited in this fashion remains uncertain, in part due to the difficulty in standardization.

Beta-blockers

The mainstay of therapy for many years has been beta-adrenergic blockade. Chest pain and dyspnea are often relieved by propranolol, but improved exercise capacity is seen less often. The response appears to be dose dependent, and very high dosage levels have often been tried. Side effects such as fatigue, depression, sleep disorders, and impaired school performance are often encountered at these high dosage levels, particularly in children and adolescents, and can be intolerable. Despite early improvement, symptoms often recur, and may not respond to dose escalation. Studies of the impact of beta-blocker therapy on survival in adults and children have invariably been uncontrolled but have not identified a measurable effect of propranolol on survival. In a single uncontrolled study in children, comparison of a small number of pediatric patients in each of two geographically distinct areas, one of which treated all HCM patients with high dose propranolol, found unusually high mortality (52% 10 year survival) in the untreated cohort with no mortality in the treated cohort 30. It is difficult to reconcile these findings with the many prior, larger studies that have failed to identify a survival benefit from propranolol and the high mortality in the untreated group is difficult to reconcile with large pediatric studies that have found a 10 year survival of 80% in unselected populations 4. Differential therapy based solely on geographic location is potentially highly biased due to the potential for genetically similar patients in each geographic region, and the differences in outcome do not exceed those observed between other studies in small groups of pediatric patients with HCM.

Calcium channel blockers

Calcium channel blockers in general and verapamil in particular have been used extensively in patients with FHC. Sustained improvement in diastolic relaxation is generally noted in response to verapamil administration with secondary reduction in diastolic pressure and mean left atrial pressure 31;32, resulting in a reduction in dyspnea and increase in exercise capacity. Improved distribution of subendocardial flow and diminished inducible ischemia have been noted as well 33. Although verapamil may exacerbate congestive heart failure in older patients, pediatric tolerance has been excellent, even in neonates 34.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system has a favorable impact on ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic function in secondary hypertrophy, but has rarely been used in FHC. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors given to patients with dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction result in a fall in cavity size and increase in outflow gradient, as well as impaired left ventricular relaxation and compliance 35. Based on theoretical considerations and data such as these, it is generally believed that these agents as well as other systemic vasodilators are contraindicated in HCM when left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is present. However, there are also recent data indicating a significant role for aldosterone 15 and the renin-angiotensin system in general 36 in modulating the phenotypic manifestations of HCM, leading to the suggestion that blocking this system might reduce hypertrophy and fibrosis 37.

Pacemaker therapy

Despite a wave of enthusiasm for asynchronous ventricular pacing for treatment of symptoms in patients with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, this therapy has largely fallen into disfavor. Results in small cohorts of children with outflow obstruction who were symptomatic despite medical therapy noted symptomatic improvement, reduced outflow obstruction, reduced left ventricular hypertrophy, and improved exercise tolerance 38–40. Despite early studies 41, subsequent controlled studies found that only about 60% of subjects improved. Furthermore, in 2/3 of these the benefit appeared to reflect placebo effect and an adverse effect on symptoms was seen in 5% 42. The significant placebo effect has been seen in other studies 43, perhaps explaining reports of persistent symptom relief after pacing termination 44, an effect not confirmed in later studies 45. Based on current information, dual chamber pacing should at best be considered as an alternative to surgical or transcatheter septal reduction in patients with obstructive FHC who are symptomatic despite maximum medical therapy and are poor candidates for other interventions.

Alcohol Septal Ablation

Direct transcatheter infusion of absolute alcohol directly into septal coronary perforators can result in tissue infarction, reduction in septal thickness, and relief of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, with symptomatic improvement and increased exercise tolerance. Toxicity has included a 1–2% rate of procedural death, 20–50% incidence of transient heart block and a 10–20% incidence of permanent complete heart block 46;47, peri-procedure ventricular arrhythmias that may require cardioversion, unintended distal infarction due to inadvertent alcohol infusion into the anterior descending coronary, and late appearance of complete heart block. Success is highest when obstruction is related to basilar septal hypertrophy. Patients with mitral valve abnormalities or obstruction that is more apical are poor candidates. Late outcome is unknown for this new technique, but current results indicate this may represent a reasonable alternative to surgery for relief of outflow tract obstruction in selected patients 48. Recently, coil occlusion of these vessels has been reported as an alternative method of inducing controlled infarction 49. Heart block was not seen in this series, the size of the infarction was smaller than with alcohol ablation, and the reduction in outflow gradient was less. The relative advantages to these two techniques remains to be determined.

Surgical myectomy

In symptomatic subaortic stenosis, septal myotomy-myectomy results in symptomatic improvement in nearly all patients and most contemporary studies have documented a high success rate, near zero mortality, and few complications with the procedure in adults 50–52. Results in children have been similar to those reported in adults 53;54. Mitral regurgitation often improves in response to myectomy due to improved intraventricular flow patterns and surgery permits concomitant mitral valve repair in patients with underlying mitral valve abnormalities. Although recurrence of obstruction is rare in older patients (2% 55), it is more frequent in the neonate and infant.

Implications for children

In the absence of symptoms, medical therapies have no proven benefits. Propranolol or verapamil are the first line therapy for symptomatic patients. If symptoms are unresponsive to medical therapy and outflow tract obstruction is present, particularly if associated with mitral regurgitation, reduction or elimination of the outflow gradient should be considered. The technical feasibility of transcatheter septal reduction in adolescents has been demonstrated, though experience in this age group is at present limited to case series. The higher procedural complication rate compared with myectomy and concerns for potential late risks associated with a large infarction have led most clinicians to await longer term results prior to use in children. Younger patients are not considered candidates for this procedure due to the inability to cannulate the smaller coronary feeder vessels in these patients. Therefore, surgical myectomy is generally recommended for management of medically intractable symptoms.

Prevention of Sudden death

Exercise restriction

Avoidance of high intensity exercise is generally recommended for patients with FHC. The rational for this restriction is based on the observations that sudden death is the usual cause of death in FHC and has a higher than expected association with exercise 56. Nevertheless, the basis for this recommendation has several serious weaknesses 57. The true incidence of FHC in athletes who experience sudden death is uncertain since genetic confirmation was not available and diagnosis was based on morphologic criteria that cannot unequivocally differentiate FHC from physiologic hypertrophy. It is clear that some patients with FHC tolerate intense, competitive athletic participation without symptoms or sudden death 58. Population studies have documented the apparent paradox that although there is a transient increase in the risk for sudden death during intense exercise in patients with coronary artery disease who regularly participate in low and high level exertion, these individuals experience an overall reduction in the risk for sudden death 59;60. Additionally, individuals who do not exercise regularly have an exaggerated risk of sudden death during exercise 61. In fact, it is precisely those individuals with cardiovascular risk factors who derive the largest risk reduction from regular participation in moderate to intense exercise 61. Several population studies have now documented that exercise and sports participation during childhood are predictive of activity level in adults 62. Detraining and social stigmatization are particularly difficult problems for the adolescent who is excluded from the usual school activities and peer interactions. Competitive team sports elicit an emotional overlay that appears to increase the risk associated with the sport itself, in addition to demanding more intense exercise, and can therefore be justifiably proscribed. Certain activities, such as weight lifting, are associated with high levels of circulating catecholamines that can predispose to arrhythmias and elicit a marked stimulus to eccentric cardiac hypertrophy. However, in patients who do not manifest high grade arrhythmias or exercise-induced arrhythmias or hypotension, there is little evidence to indicate that moderate aerobic-type exercise represents a significant risk and it does provide measurable hemodynamic and psychological benefits.

Antiarrhythmics

Although most instances of sudden death in FHC are arrhythmic events, antiarrhythmic therapy has not been effective 63. Amiodarone was initially reported to reduce the incidence of sudden death in certain high-risk subgroups, but subsequent studies indicated an increased risk of sudden death 64. Furthermore, the pediatric experience with amiodarone therapy for FHC is very limited due to the toxicity associated with chronic therapy. The promising early experience with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) has resulted in a shift to recommending an ICD for patients with ventricular tachycardia on Holter monitor or resuscitated cardiac arrest 65.

ICD Implantation

The incidence of sudden death in HCM is less than 1% per year in both adults and children and ICDs are not without hazard, including, reduced quality of life, depression, anxiety, and inappropriate discharges that can at times be fatal. Optimization of the risk-benefit for ICD use is therefore dependent on the ability to identify individuals at high risk for sudden death. A number of risk factors for sudden death in adults with HCM have been proposed (List 2), and it is worth noting that this list continues to evolve with the introduction of newly proposed risk factors in addition to both the promotion and demotion of those previously proposed 66;67. Very few series have been focused on children, with severity of hypertrophy (wall thickness z-score >6) and an abnormal blood pressure response to exercise having been confirmed as risk factors in young patients 68;69. The understanding of several of the proposed risk factors in List 2 has changed based on recent data and these newer findings are worth specific discussion.

List 2.

Risk factors for Sudden Death in HCM

| Generally Agreed | Conflicting or Insufficient Data |

|---|---|

| Aborted sudden death | Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction |

| Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia | Late hyper-enhancement on MRI |

| Family history of sudden death | Specific, “high risk” mutations |

| Syncope | Atrial fibrillation |

| Extreme hypertrophy | Myocardial bridging |

| Abnormal blood pressure response to exercise |

Arrhythmias

Ventricular arrhythmias including ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation are common, and are the presumed mechanism of sudden death in most cases. Despite this, there are conflicting data concerning the prognostic implications of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) found on Holter monitor recording in patients with FHC. The presence of asymptomatic NSVT on Holter monitoring has been reported as a risk factor in some series 70 but not in others 71;72. These differences may relate to age distribution included in each study since NSVT is generally associated with a low incremental risk (relative risk 2–2.5) which appears to be higher in adults under age 30 (22% versus 5% 5-year risk of sudden death) 70. Similarly, in children NSVT on Holter monitoring is less frequent than in adults 73 but when present appear to be associated with a higher annual risk of sudden death.

Extreme hypertrophy

Several recent reports have evaluated the impact of the severity of left ventricular hypertrophy on survival and risk of sudden death. Extreme wall thickness, in particular, has been suggested as an important risk factor 74 and therefore as a potential indication for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator 75. Other reports have not confirmed this association 76–78. These conflicting data may in part be related to the observation that the increase in risk is primarily incurred in patients presenting under age 30.79 Further supporting this concept, severity of hypertrophy has also been found to be a risk factor in children 68.

Outflow tract obstruction

The clinical importance of outflow obstruction has been highly controversial over the years, as recently recounted in some detail by Maron 26. The reduced survival in patients with outflow tract obstruction has been primarily related to death due to congestive heart failure 27 with at most a small increase in risk of sudden death. Most studies have failed to identify any relationship to sudden death 80. Surgical or pharmacologic reduction in the outflow gradient in symptomatic patients is usually associated with a reduction in symptoms and possibly improved overall survival, although there are no data to suggest that the incidence of sudden death is reduced. In patients with an ICD, a reduction in “appropriate discharges” after myectomy has been documented and has been proposed as a surrogate for a reduction in sudden death 81. However, the accuracy of this surrogate is questionable since “appropriate discharges” occur at a far higher rate than the expected rate of sudden death. Based on current data, intervention based on gradient alone or for the purpose of averting sudden death cannot be recommended.

Myocardial Bridging

Muscle bands overlying epicardial coronary arteries (myocardial bridges) are congenital and sufficiently common that they are considered an anatomic variant rather than a congenital anomaly, having been observed in 20 to 66% of hearts 82. In a provocative report of a relationship between sudden death and the presence of myocardial bridging in children with FHC 83, Yetman et al suggest that surgical unroofing of the coronary can prevent sudden death. It is unclear why myocardial bridges would have a greater impact on children than has been described in adults, where bridging is extremely common and does not appear to represent a risk for sudden death 84. Perhaps more troubling is the observation in this report 83 that patients with bridges were older than the patients without, and the overall incidence (28%) was identical to the frequency described in adults (30% 85) in contrast to the diminishing prevalence that would be anticipated in a congenital disorder that represents a risk for sudden death. Thus, although surgical intervention is possible 86, further confirmation is required before myocardial bridging can be accepted as an adverse risk factor worthy of surgical intervention.

Syncope

Unexplained syncope (that is, excluding neurally-mediated syncope) has been identified as a risk factor for sudden death in adult series, but the relative risk was only 1.8 87, although the risk was much higher in patients <18 years of age (hazard ratio 8), although the limited number of children and adolescents in this series limits the strength of the conclusion. Interestingly, recurrent episodes did not appear to increase this risk.

Delayed hyper-enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging (DHE-MRI)

DHE-MRI has been identified as a sensitive imaging technique for myocardial scar, correlating with histologically proven myocardial fibrosis 88. Myocardial scar is a known risk factor for ventricular arrhythmias and DHE-MRI is noted more frequently in patients with HCM who manifest NSVT than those who do not 89;90. Based on current data, the increase in 5-year risk of sudden death in adults with DHE-MRI has been estimated at 1.6 91.

Implications for children

With the exception of aborted sudden death, the various clinical parameters associated with increased risk of sudden cardiac death have low positive predictive value. The presence of multiple risk factors incurs higher risk, leading to the recommendation that ICD use should be limited to patients who manifest multiple risk factors 78. Nevertheless, current methods for risk stratification remain inadequate insofar as, based on current ICD utilization rates after implantation in high risk subjects and an anticipated device lifespan of 5 years, 83% of devices will be not be used prior to replacement 92. This dilemma is further compounded in children, for whom the risk-benefit ratio for the use of ICD’s is less favorable than in adults. In a recent review, 28% of children experienced appropriate, potentially life-saving ICD discharges, 25% experienced inappropriate discharges, and there was a 21% incidence of lead failure 93. Children are also at higher risk for device-related infections and adverse psychosocial impact than adults. Therefore, although potentially life-saving, pediatric-specific implantation indications must be developed and tested before this technology will achieve its full potential in children. At present, our institution has adopted an age-adjusted management approach. Aborted sudden death is considered an indication for ICD regardless of age. An ICD is recommended for adolescents with two or more of the other accepted risk factors. For pre-adolescents, additional evidence of risk is required before primary prevention is considered.

Summary

This review emphasizes the recent data concerning the etiology, natural history, management, and outcome in the diverse set of diseases that fall within the clinical phenotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Changes in the understanding of the genetics of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and the escalating clinical utility of genotyping, particularly in children, are discussed. There is a large observational literature concerning familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in adults with a much smaller body of data in children. This review summarizes those situations in which the findings in children have been found to be different from the information available from adult cohorts and emphasizes how certain of the management recommendations must be modified when applied to pediatric patients.

Synopsis

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has important differences in children compared with adults, particularly with regard to the range of causes and the outcomes in infants. Survival is highly dependent on etiology, particularly in the youngest patients, and pursuit of the specific cause is therefore necessary. The clinical utility of defining the genotype in children with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy exceeds that at other ages and has a highly favorable cost-benefit ratio. Although most of the available information concerning treatment and prevention of sudden death is derived in adults, management of children requires consideration of the differences in age-specific risk:benefit ratios.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant No. 5 R01 HL53392-09 from the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Lipshultz SE, Sleeper LA, Towbin JA, et al. The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1647–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutka DP, Donnelly JE, Nihoyannopoulos P, et al. Marked variation in the cardiomyopathy associated with Friedreich’s ataxia. Heart. 1999;81(2):141–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regalado JJ, Rodriguez MM, Ferrer PL. Infantile hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of glycogenosis Type IX: isolated cardiac phosphorylase kinase deficiency. Pediatr Cardiol. 1999;20(4):304–7. doi: 10.1007/s002469900471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colan SD, Lipshultz SE, Lowe AM, et al. Epidemiology and cause-specific outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in children: findings from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. Circulation. 2007;115(6):773–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geier C, Perrot A, Özcelik C, et al. Mutations in the human muscle LIM protein gene in families with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003;107(10):1390–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000056522.82563.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos JM, Towbin JA, Ackerman MJ. Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications of genetic testing for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(3):201–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakaura H, Morimoto S, Yanaga F, et al. Functional changes in troponin T by a splice donor site mutation that causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1999;277(2):C225–C232. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.2.C225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marian AJ, Roberts R. The molecular genetic basis for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33(4):655–70. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arad M, Benson DW, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Constitutively active AMP kinase mutations cause glycogen storage disease mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(3):357–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogensen J, Murphy RT, Shaw T, et al. Severe disease expression of cardiac troponin C and T mutations in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(10):2033–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moolman JC, Corfield VA, Posen B, et al. Sudden death due to troponin T mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29(3):549–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00530-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anan R, Shono H, Kisanuki A, et al. Patients with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by a Phe110Ile missense mutation in the cardiac troponin T gene have variable cardiac morphologies and a favorable prognosis. Circulation. 1998;98(5):391–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbustini E, Fasani R, Morbini P, et al. Coexistence of mitochondrial DNA and β myosin heavy chain mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with late congestive heart failure. Heart. 1998;80(6):548–58. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.6.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Driest SL, Vasile VC, Ommen SR, et al. Myosin binding protein C mutations and compound heterozygosity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(9):1903–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortlepp JR, Vosberg HP, Reith S, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system associated with expression of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a study of five polymorphic genes in a family with a disease causing mutation in the myosin binding protein C gene. Heart. 2002;87(3):270–5. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burn J, Camm J, Davies MJ, et al. The phenotype/genotype relation and the current status of genetic screening in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Marfan syndrome, and the long QT syndrome. Heart. 1997;78(2):110–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semsarian C, Ahmad I, Giewat M, et al. The L-type calcium channel inhibitor diltiazem prevents cardiomyopathy in a mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(8):1013–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI14677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colan SD, Sanders SP, Borow KM. Physiologic hypertrophy: effects on left ventricular systolic mechanics in athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;9(4):776–83. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maron BJ. Distinguishing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from athlete’s heart physiological remodelling: clinical significance, diagnostic strategies and implications for preparticipation screening. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(9):649–56. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.054726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sluysmans T, Colan SD. Theoretical and empirical derivation of cardiovascular allometric relationships in children. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(2):445–57. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01144.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charron P, Dubourg O, Desnos M, et al. Diagnostic value of electrocardiography and echocardiography for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in genotyped children. Eur Heart J. 1998;19(9):1377–82. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagueh SF, McFalls J, Meyer D, et al. Tissue Doppler imaging predicts the development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in subjects with subclinical disease. Circulation. 2003;108(4):395–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084500.72232.8D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poutanen T, Tikanoja T, Jaaskelainen P, et al. Diastolic dysfunction without left ventricular hypertrophy is an early finding in children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-causing mutations in the beta-myosin heavy chain, alpha-tropomyosin, and myosin-binding protein C genes. Am Heart J. 2006;151(3):725. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McTaggart DR. Tissue doppler imaging in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without left ventricular hypertrophy. Heart Lung Circ. 2002;11(2):92–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1444-2892.2002.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelliccia A, Zipes DP, Maron BJ. Bethesda Conference #36 and the European Society of Cardiology Consensus Recommendations revisited a comparison of U.S. and European criteria for eligibility and disqualification of competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(24):1990–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maron BJ, Maron MS, Wigle ED, et al. The 50-year history, controversy, and clinical implications of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(3):191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maron MS, Olivotto I, Betocchi S, et al. Effect of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on clinical outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(4):295–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah JS, Esteban MT, Thaman R, et al. Prevalence of exercise-induced left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in symptomatic patients with non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2008;94(10):1288–94. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.126003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kizilbash AM, Heinle SK, Grayburn PA. Spontaneous variability of left ventricular outflow tract gradient in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1998;97(5):461–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostman-Smith I, Wettrell G, Riesenfeld T. A cohort study of childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: improved survival following high-dose beta-adrenoceptor antagonist treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(6):1813–22. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Posma JL, Blanksma PK, Van der Wall E, et al. Acute intravenous versus chronic oral drug effects of verapamil on left ventricular diastolic function in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;24(6):969–73. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199424060-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartmann A, Schnell J, Hopf R, et al. Persisting effect of Ca(2+)-channel blockers on left ventricular function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after 14 years’ treatment. Angiology. 1996;47(8):765–73. doi: 10.1177/000331979604700803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gistri R, Cecchi F, Choudhury L, et al. Effect of verapamil on absolute myocardial blood flow in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(4):363–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moran AM, Colan SD. Verapamil therapy in infants with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Young. 1998;8(3):310–9. doi: 10.1017/s1047951100006818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kyriakidis M, Triposkiadis F, Dernellis J, et al. Effects of cardiac versus circulatory angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on left ventricular diastolic function and coronary blood flow in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1998;97(14):1342–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.14.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsybouleva N, Zhang LF, Chen SN, et al. Aldosterone, through novel signaling proteins, is a fundamental molecular bridge between the genetic defect and the cardiac phenotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;109(10):1284–91. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121426.43044.2B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamazaki T, Suzuki J, Shimamoto R, et al. A new therapeutic strategy for hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy in humans. A randomized and prospective study with an Angiotensin II receptor blocker. Int Heart J. 2007;48(6):715–24. doi: 10.1536/ihj.48.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alday LE, Bruno E, Moreyra E, et al. Mid-term results of dual-chamber pacing in children with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Echocardiogr J Cardiovasc Ultrasound Allied Tech. 1998;15(3):289–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.1998.tb00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rishi F, Hulse JE, Auld DO, et al. Effects of dual-chamber pacing for pediatric patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29(4):734–40. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dimitrow PP, Podolec P, Grodecki J, et al. Comparison of dual-chamber pacing with nonsurgical septal reduction effect in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2004;94(1):31–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fananapazir L, Epstein ND, Curiel RV, et al. Long-term results of dual-chamber (DDD) pacing in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Evidence for progressive symptomatic and hemodynamic improvement and reduction of left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1994;90(6):2731–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.6.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishimura RA, Trusty JM, Hayes DL, et al. Dual-chamber pacing for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29(2):435–41. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00473-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linde C, Gadler F, Kappenberger L, et al. Placebo effect of pacemaker implantation in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83(6):903–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)01065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fananapazir L, Cannon RO, III, Tripodi D, et al. Impact of dual-chamber permanent pacing in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with symptoms refractory to verapamil and β-adrenergic blocker therapy. Circulation. 1992;85(6):2149–61. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.6.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gadler F, Linde C, Rydén L. Rapid return of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and symptoms following cessation of long-term atrioventricular synchronous pacing for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83(4):553–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00912-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Togni M, Billinger M, Cook S, et al. Septal myectomy: cut, coil, or boil? Eur Heart J. 2008;29(3):296–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorajja P, Valeti U, Nishimura RA, et al. Outcome of alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2008;118(2):131–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.738740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimmelstiel CD, Maron BJ. Role of percutaneous septal ablation in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;109(4):452–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114144.40315.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Durand E, Mousseaux E, Coste P, et al. Non-surgical septal myocardial reduction by coil embolization for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: early and 6 months follow-up. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(3):348–55. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woo A, Williams WG, Choi R, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic determinants of long-term survival after surgical myectomy in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;111(16):2033–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000162460.36735.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishimura RA, Holmes DR., Jr Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(13):1320–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp030779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smedira NG, Lytle BW, Lever HM, et al. Current effectiveness and risks of isolated septal myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(1):127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minakata K, Dearani JA, O’Leary PW, et al. Septal myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in pediatric patients: early and late results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(4):1424–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menon SC, Ackerman MJ, Ommen SR, et al. Impact of septal myectomy on left atrial volume and left ventricular diastolic filling patterns: an echocardiographic study of young patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21(6):684–8. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Minakata K, Dearani JA, Schaff HV, et al. Mechanisms for recurrent left ventricular outflow tract obstruction after septal myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(3):851–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Semsarian C, Richmond DR. Sudden cardiac death in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an Australian experience. Aust N Z J Med. 1999;29(3):368–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1999.tb00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shephard RJ. The athlete’s heart: is big beautiful? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1996;30(1):5–10. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.30.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maron BJ, Klues HG. Surviving competitive athletics with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73(15):1098–104. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedewald VE, Jr, Spence DW. Sudden cardiac death associated with exercise: The risk- benefit issue. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66(2):183–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90585-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kohl HW, Powell KE, Gordon NF, et al. Physical activity, physical fitness, and sudden cardiac death. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1992;14(1):37–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richardson CR, Kriska AM, Lantz PM, et al. Physical activity and mortality across cardiovascular disease risk groups. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(11):1923–9. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000145443.02568.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beunen GP, Lefevre J, Philippaerts RM, et al. Adolescent correlates of adult physical activity: a 26-year follow-up. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(11):1930–6. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000145536.87255.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tung R, Zimetbaum P, Josephson ME. A critical appraisal of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy for the prevention of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(14):1111–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fananapazir L, Leon MB, Bonow RO, et al. Sudden death during empiric amiodarone therapy in symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67(2):169–74. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90440-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Melacini P, Maron BJ, Bobbo F, et al. Evidence that pharmacological strategies lack efficacy for the prevention of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2007;93(6):708–10. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.099416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maron BJ, McKenna WJ, Danielson GK, et al. American College of Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology clinical expert consensus document on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(9):1687–713. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elliott P, Spirito P. Prevention of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related deaths: theory and practice. Heart. 2008;94(10):1269–75. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.154385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Decker JA, Rossano JW, Smith EO, et al. Risk factors and mode of death in isolated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(3):250–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ostman-Smith I, Wettrell G, Keeton B, et al. Echocardiographic and electrocardiographic identification of those children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who should be considered at high-risk of dying suddenly. Cardiol Young. 2005;15(6):632–42. doi: 10.1017/S1047951105001824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Monserrat L, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, et al. Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: An independent marker of sudden death risk in young patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(5):873–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Montereggi A, et al. Prognostic value of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia and the potential role of amiodarone treatment in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: assessment in an unselected non-referral based patient population. Heart. 1998;79(4):331–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.4.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kofflard MJM, ten Cate FJ, Van Der Lee C, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a large community-based population: Clinical outcome and identification of risk factors for sudden cardiac death and clinical deterioration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(6):987–93. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)03004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McKenna WJ, Franklin RCG, Nihoyannopoulos P, et al. Arrhythmia and prognosis in infants, children and adolescents with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11(1):147–53. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spirito P, Maron BJ. Relation between extent of left ventricular hypertrophy and occurrence of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(7):1521–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)92820-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, et al. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(24):1778–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006153422403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Montereggi A, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Tuscany: Clinical course and outcome in an unselected regional population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26(6):1529–36. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Spirito P, et al. Epidemiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related death - Revisited in a large non-referral-based patient population. Circulation. 2000;102(8):858–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Elliott PM, Blanes JRG, Mahon NG, et al. Relation between severity of left-ventricular hypertrophy and prognosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2001;357(9254):420–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR, et al. Use of echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: clinical implications of massive hypertrophy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19(6):788–95. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Efthimiadis GK, Parcharidou DG, Giannakoulas G, et al. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction as a risk factor for sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(5):695–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McLeod CJ, Ommen SR, Ackerman MJ, et al. Surgical septal myectomy decreases the risk for appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator discharge in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(21):2583–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamaguchi M, Tangkawattana P, Hamlin RL. Myocardial bridging as a factor in heart disorders: Critical review and hypothesis. Acta Anat (Basel) 1996;157(3):248–60. doi: 10.1159/000147887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yetman AT, McCrindle BW, MacDonald C, et al. Myocardial bridging in children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy - a risk factor for sudden death. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(17):1201–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810223391704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Basso C, Thiene G, Mackey-Bojack S, et al. Myocardial bridging, a frequent component of the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype, lacks systematic association with sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(13):1627–34. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miller GL. Functional assessment of coronary stenoses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(4):1134. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hillman ND, Mavroudis C, Backer CL, et al. Supraarterial decompression myotomy for myocardial bridging in a child. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68(1):244–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spirito P, Autore C, Rapezzi C, et al. Syncope and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;119(13):1703–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.798314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moon JC, Reed E, Sheppard MN, et al. The histologic basis of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(12):2260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dimitrow PP, Klimeczek P, Vliegenthart R, et al. Late hyperenhancement in gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: comparison of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with and without nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;24(1):77–83. doi: 10.1007/s10554-007-9209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kwon DH, Smedira NG, Rodriguez ER, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance detection of myocardial scarring in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: correlation with histopathology and prevalence of ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(3):242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nazarian S, Lima JA. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for risk stratification of arrhythmia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(14):1375–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maron BJ, Spirito P, Shen WK, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and prevention of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298(4):405–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alexander ME, Cecchin F, Walsh EP, et al. Implications of implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in congenital heart disease and pediatrics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15(1):72–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]