Abstract

Background

During normal breathing, the mesothelial surfaces of the lung and chest wall slide relative to one another. Experimentally, the shear stresses induced by such reciprocal sliding motion are very small, consistent with hydrodynamic lubrication, and relatively insensitive to sliding velocity, similar to Coulomb-type dry friction. Here we explore the possibility that shear-induced deformation of surface roughness in such tissues could result in bidirectional load supporting behavior, in the absence of solid-solid contact, with shear stresses relatively insensitive to sliding velocity.

Method of approach

We consider a lubrication problem with elastic blocks (including the rigid limit) over a planar surface sliding with velocity U , where the normal force is fixed (hence the channel thickness is a dependent variable). One block shape is continuous piecewise linear (V block), the other continuous piecewise smoothly quadratic (Q block). The undeformed elastic blocks are spatially symmetric; their elastic deformation is simplified by taking it to be affine, with the degree of shape asymmetry linearly increasing with shear stress.

Results

We find that the V block exhibits nonzero Coulomb-type starting friction in both the rigid and elastic case, and that the smooth Q block exhibits approximate Coulomb friction in the sense that the rate of change of shear force with U is unbounded as U → 0 ; shear force ∝U1/ 2 in the rigid asymmetric case and ∝U1/ 3 in the (symmetric when undeformed) elastic case. Shear-induced deformation of the elastic blocks results in load supporting behavior for both directions of sliding.

Conclusions

This mechanism could explain load-supporting behavior of deformable surfaces that are symmetrical when undeformed, and may be the source of the weak velocity dependence of friction seen in the sliding of lubricated, but rough, surfaces of elastic media such as the visceral and parietal pleural surfaces of the lung and chest wall.

Keywords: lubrication theory, elastohydrodynamic lubrication, pleural space

Introduction

In the pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities, organs slide against the body wall, their delicate mesothelial surfaces lubricated by an aqueous serosal liquid. The nature of the physical interaction between opposing serosal surfaces lung and chest wall has been controversial [1, 2]. Agostoni and D’Angelo [1] maintained that the average normal stress or “surface pressure” applied to the lung was greater than that of the pleural liquid, attributing the difference in pressure to physical points of contact between lungs and chest wall. Subsequently, Lai-Fook and others [3] found surface and liquid pressures to be equal, proposing that the lung and chest wall are essentially completely separated by pleural liquid. Several investigations have probed the presence or absence of stress-bearing physical contact between surfaces by measuring the tribological behavior of sliding mesothelial tissues. Thus, a coefficient of friction independent of velocity, as is characteristic of boundary lubrication, was taken as evidence that contact between asperities supports most of the normal load [4, 5]. Conversely a coefficient of friction that varied with velocity, as is characteristic of elastohydrodynamic lubrication, was taken as evidence that the lubricating liquid largely separates the surfaces and supports the load [6].

During the course of our investigations into the tribology of mesothelial tissues, we hypothesized that during the reciprocating sliding of lung against chest wall associated with breathing, shear-induced deformation and smoothing of surface roughness could lead to redistribution of pleural fluid and load supporting behavior that locally increases pleural space thickness, separating the sliding surfaces [7-10]. We were particularly interested in the possibility that hydrodynamic lubrication, without contact between asperities, might mimic dry Coulomb friction and boundary lubrication, in which the coefficient of friction is nearly constant over a range of low sliding velocities U . Finally, perhaps the most important feature that we needed to capture was that a positive normal force FT be supported under both phases of the reciprocating motion that occurs in breathing; note that symmetry of FT with U is opposite to the expected antisymmetry of FT in a more typical lubrication problem without elastic deformation.

To investigate this, we considered a model system with the following general features (specifics are detailed below). Fluid, in two dimensional channel Stokes flow and in the lubrication approximation, is bounded on the top by an elastic medium with a simplified constitutive law and on the bottom by a rigid planar surface moving with velocity U . All solutions are steady state, and therefore transient effects, including starting friction, are not considered. The roughness of the elastic body is approximated by continuous piecewise linear or quadratic shapes. The gap thickness is free to vary; it is determined by the condition of supporting a given normal load. The elastic media are spatially symmetric when undeformed; the constitutive law specifies an affine deformation axially such that the degree of spatial asymmetry is proportional to the net tangential force, or integrated shear stress.

We find two novel features in the solutions for this simplified elastohydrodynamics problem: (1) The elastic blocks are load supporting independent of the direction of sliding. (2) The solutions mimic important features of Coulomb-type friction, displaying either nonzero starting friction or sharply increasing friction with U , and, except near U = 0 , a weak dependence of friction coefficient on U . (3) Finally, we find a new nondimensional representation that collapses the results onto master relationships.

The general problem

Geometry

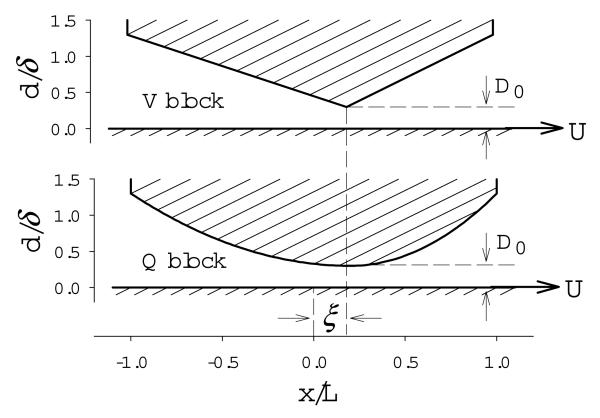

Fig. 1 shows two types of two-dimensional solid blocks (the precise shapes of the V and Q blocks are defined below), at rest and of length 2L. The axial coordinate is x ∈[−L, L]. Below the block is a channel of fluid with viscosity μ, bounded below by a rigid flat plate moving in the positive x direction with velocity U . The channel depth is denoted d(x). The block is either rigid or elastic. For the rigid block we simply specify d(x) to establish a fixed asymmetry. For the elastic block, we specify d(x) when it is undeformed, and a piecewise affine change in d(x) that depends on the induced shear forces for the deformed elastic case (see below under Asymmetry and the constitutive law). d(x) for the V block is continuous, with two linear segments; d(x) for the Q block is continuously differentiable, with two quadratic segments. The two segments join at the point ξL, ∣ξ∣ ≤ 1, at which the slope is zero. For both V and Q blocks, we take d(−L) = d(L) .

Fig. 1.

Top panel. Geometry of the linear V block. The channel height d is a linear (continuous) function in both of its two segments, and is normalized by the surface “roughness” δ, given by max(d) – min(d) . The degree of asymmetry is ξ = 0.2 . This is the point x / L at which the channel height is minimal. The dimensionless minimal channel height is given by D0 = 0.3. The bottom surface is flat and is sliding in the positive x direction with velocity U .

Bottom panel. Geometry of the quadratic Q block. The channel height is a quadratic function in both of its two segments and horizontal where they join. The Q block geometry is shown for the same degree of asymmetry and minimal channel height D0.

The boundary conditions are that the pressure be zero at the two ends, P(−L) = P(L) = 0. The channel depth d(x) is taken to be everywhere small compared with L , and (d / dx)d(x) <<1. Finally, we consider only the circumstance in which inertial forces are negligible and the motion is in steady state. These criteria suffice for the applicability of classical lubrication theory [11]. The block’s overall height is determined by fixing the total normal load; this is achieved through letting d(x) change by a uniform additive term.

Asymmetry and the constitutive law

The parameter ξ is a measure of the asymmetry: ξ = 0 corresponds to perfect symmetry about x = 0 ; ξ = 1 (−1) corresponds to complete asymmetry in the sense that the right (left) hand segment is entirely missing. For a rigid body ξ is fixed a priori. For the elastic body, we simplify the coupled Stokes flow/elastic body interaction by allowing affine deformation of the blocks in the axial direction (but with no change in surface roughness). We take the undeformed elastic block shape to be symmetric (ξ = 0 ). The asymmetry increases with the tangential forces due to sliding friction, and for simplicity, we let this relationship be homogeneously linear. We set ξ = FT/Φ, where Φ is a material modulus of rigidity (with dimensions of force). Φ can be related to a more usual material shear modulus by noting that ξ is the strain associated with a shear stress of FT / 2L for unit channel width, and so Φ may be identified as 2L times width times the more usual shear modulus.

Dimensional volume flux, normal and tangential forces

For a given (fixed) channel depth function, the solutions for the volume flux, tangential force (which we take on the bottom boundary), and normal force are all given by well-known elementary techniques [11], which we summarize here. With respect to the coordinate normal to flow, the local fluid velocity consists of a linear term (pure shear, proportional to U ) and a quadratic term (Poiseuille, proportional to dP / dx). Integration of the axial velocity over the normal coordinate yields the volume flux Q per unit width, which in turn is a sum of two terms—the shear flow term is proportional to velocity, and the Poiseuille flow is proportional to the pressure gradient. Since in steady state, the volume flux is constant along the axial coordinate (i.e. conservation of mass), this gives an explicit equation for the pressure gradient in terms of the volume flow and velocity. The conservation law and pressure equations then follow immediately; these are given by

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

Here d ≡ d(x) is understood. The total normal force FN per unit width is given by integrating Eq. (2),

| (3) |

while the tangential force FT per unit width applied to the bottom surface to effect the motion is given by integrating the gradient of the velocity at that surface, giving

| (4) |

Nondimensionalization

There are a number of parameters with dimensions of length that can be used for constructing nondimensional groups. We choose the following. Let d0 = min(d) be the minimum channel height, and δ = max(d) – d0 be the amplitude of variation of the channel height, i.e. the dimensional “roughness height”. Define the nondimensional channel height and minimum height by D = d /δ , D0 = d0 /δ. Let r = δ / 2L be the surface “roughness”. For the axial nondimensional coordinate, we define w by x = ξL ∓ (1 ± ξ)Lw for x in the left and right hand segments respectively. This leads to a common range for w : for both segments w ∈[0,1]; w = 0 corresponds to x = ξL , the point common to both segments and w = 1 corresponds to the left and right boundaries x = ±L .

Nondimensional normal and tangential forces

We nondimensionalize the normal and tangential forces by

| (5) |

These choices of dimensionless quantities lead to cancellation of numerous parameters. In terms of integrals over the axial coordinate w , Eqs. (1, 3, and 4) become

| (6) |

where for any function z(w), and the bracket notation is used to emphasize the nature in which these are average quantities over the segments. Finally, we nondimensionalize the velocity by defining

| (7) |

This is equivalent to the Sommerfeld parameter; it can be written as U* = (μU /δ) /(FN/ 2L), i.e. the ratio of a shear stress to a normal stress (for unit width channel). Note the simple representation of the dimensionless velocity in terms of the dimensionless normal force.

Particular solutions

Specific solution, V block

Here the channel depth is a continuous piecewise linear function, for which the nondimensionalized shape is just D = D0 + w for both segments. The top panel of Fig. 1 shows an example of a V block with degree of asymmetry ξ = 0.2 (d(x) attains its minimum at x / L = 0.2) and with nondimensional minimum channel height D0 = 0.3. For the rigid V block, ξ is fixed a priori, whereas in the elastic block ξ must be chosen to satisfy the approximate constitutive law, as described above. For any specific choice of ξ and D0, there are five integrals needed in Eqs. (6), the values of which are given in the Appendix. The results for the nondimensional normal and tangential forces are

| (8) |

Rigid V block

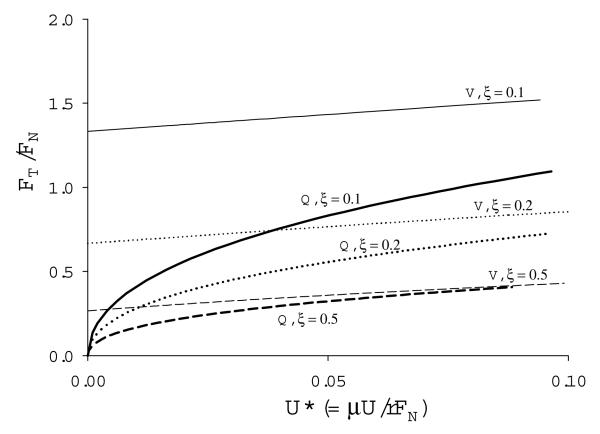

We now wish to find the frictional coefficient FT/ FN = fT/fN, as a function of the dimensionless velocity U* (Eq. (7)), where the minimal channel depth D0 is free, but where the asymmetry ξ is fixed a priori. This can be found by eliminating D0 from Eqs. (8), and using Eq. (7). Numerically, this is easily done by evaluating Eqs. (8) over a range of independently chosen values of D0. This is shown in Fig. 2 (light lines labeled V) for three specific cases of asymmetry, ξ = 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5, and for surface roughness r = 0.2. The dependence of the gap thickness D0 on velocity is of independent interest; this relationship is an immediate result of Eq. (7) and the first of Eqs. (8). It is shown in Fig. 3 for the same cases of asymmetry and surface roughness as in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Coefficient of sliding friction FT / FN versus normalized velocity, U* = μU / rFN , for rigid V blocks (light lines with V label) and rigid Q blocks (bold lines with Q label). These are shown as a family in degree of asymmetry of the blocks given by ξ = 0.1 (solid line), 0.2 (dotted line), and 0.3 (dashed line). Surface roughness is r = 0.2. At fixed U *, the friction coefficient decreases with increasing asymmetry.

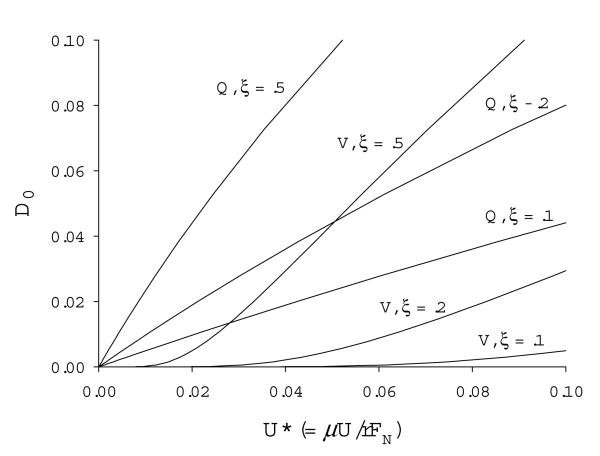

Fig. 3.

Dimensionless minimal gap thickness D0 versus normalized velocity, U* = μU / rFN. These families are for the same degree of asymmetry (ξ = 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3) and surface roughness r = 0.2 as in Fig. 2.

Importantly, in the low velocity limit, FT/ FN approaches a limiting nonzero value; this is one of the essential characteristics of Coulomb friction. Moreover, the friction is only gently increasing with U*. This can be seen by examining the low velocity limit, for which D0→0, and we have

| (9) |

and hence

| (10) |

Note that, as can be seen dramatically in Fig. 3, D0 goes to zero with U * extremely fast; in particular, from Eqs (7) and (9),

| (11) |

so for small velocities, the correction term in Eq. (9) is entirely negligible.

Elastic V block

As described above, the simplified constitutive law is taken as a homogeneous linear relation between the asymmetry and the net tangential force: ξ = FT/Φ, where Φ is the material modulus of rigidity. As we are taking the normal load as an independent variable, we require the simultaneous solution of Eqs. (8) and the constitutive condition,

| (12) |

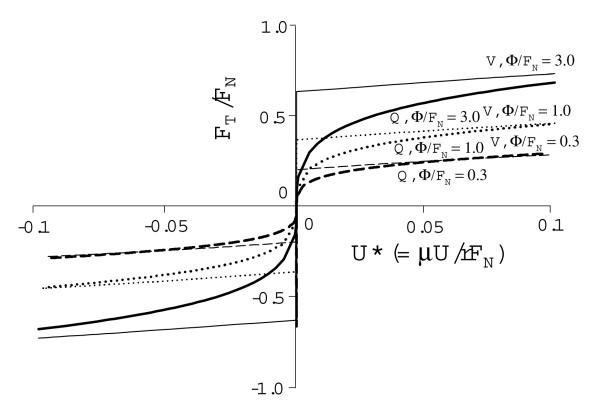

Elementary numerical means suffice to effect this solution; the result is shown in Fig. 4 (light lines labeled V), for three cases of material stiffness spanning one log: Φ/FN = 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0. As in Fig. 2, the surface roughness is given by r = 0.2.

Fig. 4.

Coefficient of sliding friction FT / FN versus normalized velocity, U* = μU / rFN, for elastic V blocks (light lines with V label) and elastic Q blocks (bold lines with Q label). These are shown as a family in material stiffness Φ of the blocks given by Φ / FN = 3.0 (solid line), 1.0 (dotted line), and 0.3 (dashed line). Surface roughness is given by r = 0.2 . At fixed U *, the friction coefficient increases with increasing material stiffness.

As in the rigid case, of most interest is the low velocity limit. This can be done analytically by substituting Eq. (12) into Eqs. (9) and (10) above. Noting that the solution for the tangential force is now strictly antisymmetric, we find

| (13) |

The elastic V block thus has the Coulomb characteristic of nonzero starting friction and is similar to Coulomb friction in that the coefficient of friction rises only gently with U *. The starting friction is substantial because FT must effect sufficient deformation such that the resulting asymmetry (and hence pressure distribution) will support the load. Most importantly, the elastic V block is (positive) load supporting independent of the direction of sliding (since FT and sgn(U*) are antisymmetric in U , it follows that FN > 0 for all nonzero U).

Specific solution, Q block

The Q block is quadratic in each of the two segments, with zero slope at x = ξL , where d(x) is minimal. See the bottom panel of Fig. 1 for an example. The nondimensional shape is given by D = D0 + w2 for each segment. Evaluation of the five integrals needed in Eqs. (6) are given in the Appendix. For given ξ and D0, the nondimensional normal and tangential forces are

| (14) |

where .

Rigid Q block

Proceeding exactly as in the V block case, the friction coefficient FT / FN as a function of velocity U * is found by eliminating D0 from Eq. (14), and using Eq. (7). Fig. 2 (bold lines labeled Q) shows this relationship for the Q block, also for the same degree of asymmetry (ξ = 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5) and surface roughness ( r = 0.2) as the V block.

The low velocity limits can be obtained from the limits as D0→0 of Eq. (14). This yields

| (15) |

and hence

| (16) |

This is Coulomb-like friction in the sense that there is a very sharp rise in friction from rest to any positive value of U * (FT / FN has a U1/ 2 singularity at the origin). However, it fails to display a nonzero starting friction since FT / FN is continuous all the way to U = 0. Note that, from Eqs. (7) and (15), the minimal gap thickness D0 goes to zero with U *, but unlike the V block, the Q block behavior is in fact asymptotically linear:

| (17) |

Fig. 3 shows the dependence of the Q block minimal gap thickness D0 on U *, again for the same degrees of asymmetry and surface roughness as the V block.

Elastic Q block

As in the V block case, we consider the degree of asymmetry ξ to be a function of the shear force, through the same simple relation given in Eq. (12). The simultaneous solution to this equation and Eq. (14) then yields the behavior of the friction coefficient. This is shown in Fig. 4 (bold lines labeled Q) for the same three cases of material stiffness as for the V block, given by Φ/FN = 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 (and for the same surface roughness r = 0.2). Using Eqs. (12, 15, and 16) for the Q block solution in the low velocity limit, we find

| (18) |

There is no nonzero starting friction per se, but similar to the rigid Q block the elastic one also shows an unbounded rise in friction near U = 0 (FT / FN has a U1/3 singularity at the origin). Importantly, the elastic Q block is also (positive) load supporting regardless of the direction of sliding (FT and U *1/3 are antisymmetric in U implies FN > 0 for all nonzero U ).

Discussion

We found that shear-induced elastic deformation of an initially symmetrical uneven sliding surface can lead to load support. This is the conclusion reached by [12] in their analysis of lubrication in a variety of soft symmetrical solids, for which, “the fluid pressure deform[ed] the solid form, thereby giving rise to a normal force.” The normal force was maximized for a particular value of η, the ratio of hydrodynamic pressure to elastic stiffness of the solid. We note that our elastic blocks do not exhibit the normal deformation that flattens the surface and reduces spatial variation in fluid thickness [8]. However, in unpublished finite-element studies of deformable two-dimensional shapes similar to our Q blocks sliding in lubricant, normal and transverse deformations were of similar magnitude. Both normal and transverse deformation serve to increase the asymmetry of the shape and increase load support. Thus, while our simplification is unrealistic in this respect, it preserves the essential feature of hydrodynamic asymmetry that occurs during EHL and maintains an affine block shape that permits computation of elastohydrodynamic load support.

In our analysis, the frictional coefficient varies only slightly with velocity, despite fully developed hydrodynamic separation, because any increase in shear stress with increasing velocity is mitigated by the increasing separation of the surfaces associated with the fixed normal load. Lubrication is often categorized by the degree to which load support is attributable to hydrodynamic pressure versus deformation of asperities [13]. In hydrodynamic lubrication at high values of the Stribeck number (μU / PN , where PN is average normal stress), the frictional coefficient increases with velocity and hydrodynamic pressure supports the load. In boundary lubrication at low μU / PN, the coefficient of friction is relatively independent of velocity, hydrodynamic pressure is relatively unimportant in load support, and the normal load is born by shear deformation of asperities that are in contact or separated from each other by a very thin film of lubricant. In mixed or elastohydrodynamic lubrication at intermediate μU / PN, the coefficient of friction often decreases with increasing velocity, and both hydrodynamic pressure and shear deformation of asperities are important in supporting the normal stress.

Note that in vivo, it is not the value of pleural pressure per se that determines the regional thickness of the lubricating liquid layer but the non-gravitational pressure gradients arising from deformation of the lung and chest wall. Because the tissues of the lung and chest wall are relatively smooth and quite soft (modulus of elasticity 300 - 1500 Pa [8]), these non-gravitational pressure gradients are estimated to be less than 200 Pa/cm [6]. Nonetheless, the resulting variations in normal stress at regions of relative prominence (e.g., the convexity over a rib or lobe of the lung) would, given enough time, cause contact. However, sliding of such tissues in the presence of lubricant generates hydrodynamic pressure that deforms the asperities to generate load support and decreases spatial variation in gap thickness [6-8, 10, 12]. The present results provide a mechanism whereby hydrodynamic lubrication might mimic boundary lubrication in exhibiting a coefficient of friction that changes little at low velocities.

Recent experimental observations in mesothelial tribology have been consistent with both boundary and elastohydrodynamic lubrication. In experiments on lung tissue sliding on chest wall, the frictional coefficient remained relatively constant as sliding speed increased, consistent with boundary lubrication [5]. By contrast, in experiments on mesothelial tissue sliding against a glass plate, the frictional coefficient first decreased and then increased with increasing speed [6], and thickness of the lubricating liquid layer beneath the mesothelial tissue increased with sliding velocity (unpublished observations), consistent with hydrodynamic pumping. Because many of our experiments showed only a weak dependence of the coefficient of sliding friction on sliding velocity [5, 6], we wondered whether a single mechanism, elastohydrodynamic lubrication, might manifest this behavior of friction with velocity, as well as hydrodynamic pumping. Our results suggest that at very low μU / PN , elastohydrodynamic lubrication may exhibit relative invariance of friction with velocity that may be difficult to distinguish from boundary lubrication.

In the pleural space, the nature of the lubrication between sliding surfaces inevitably depends on the presence or absence of contact between lung and chest wall [2]. Contact implies boundary lubrication, in which asperities on the lung and chest wall are separated only by condensed pleural liquid. Miserocchi and Agostoni [14] discussed the possibility that mesothelial and white cells in pleural liquid constitute points of contact, potentially acting as ball bearings. Agostoni suggested that boundary lubrication may be assisted by hyaluronan [1], and Hills has suggested that oligolamellar surfactants in the pleural space assist boundary lubrication [15] and act as dry lubricants [16]. However, pleural liquid is an ultrafiltrate of plasma, a Newtonian fluid with a viscosity near that of water. Hyaluronan and phospholipids are present only at very low concentrations; and their importance in pleural lubrication is speculative [2]. If, as is maintained by Lai-Fook and others, pleural liquid exists in a continuous layer between lung and chest wall [2], elastohydrodynamic lubrication would prevail except, perhaps, at very low velocities where fluid is sufficiently thin to allow molecular interactions between the surfaces. As noted below in our comments on starting friction, these are important questions, but our analysis here is restricted to the contribution of elastohydrodynamics to the frictional behavior of sliding surfaces.

Analytically, the basic ideas and solutions to two-dimensional lubrication problems of nearly parallel planar surfaces of rigid solids are classical and well-known [11]. However, analytic approaches to the extension of lubrication to include elastic deformations are hampered by serious difficulties attendant on moveable boundaries. One early approach [17] considered wedge shaped bodies in models of face seals, similar to the V blocks we consider here where the longitudinal degree of asymmetry was fixed, the distortion was taken normal to the sliding velocity. An important limitation of that work, however, is that lift was assumed to be generated only in the converging portion of the lubricating gap. Other approaches [18-20] have focused on the appearance of cavitation in regions of very low pressures in rotary lip seals and its effect on the sealing meniscus in the gap, or have considered the thermodynamic implications of variations in fluid density and temperature on lift capacity [21]. We recently used finite element methods to explore the generation of lift produced by symmetry breaking of a sliding body with an initially symmetric surface roughness [10]. Skotheim and Mahadevan [12] addressed the general behavior of a variety of geometries with both sliding and rolling, and with rigid and soft surfaces. Their results are complementary to ours, insofar as the loads supported are dependent variables (e.g. for fixed initial undeformed gap separation) whereas we have focused on the issue of changes in friction coefficient with sliding given a fixed load to support, and in particular in the low velocity limit. It will be interesting to extend their work into the specific context of deformations for given loads and to examine the resulting tangential shear stresses. Despite these differences, we note that their results confirm to a large extent the ideas used here regarding affine shear deformations particularly in the Q block case; their results on gap thickness, when deformed by both shear and normal stresses, closely conform to piecewise continuous quadratic forms about the minimal gap thickness.

Most of the results to date on the coupling of elastic bodies with hydrodynamics derive from the engineering literature, where the important problems of lubrication of face seals and rotary seals are treated. In the context of biology, there have been numerous studies on elastohydrodynamic lubrication in a variety of natural and prosthetic systems [22], and the tribology of hydrogels combines elastic deformation with chemical surface interactions that reduce the frictional coefficients of cartilage and other porous tissues [23]. There are experimental observations [24] of contact mechanics and lubrication of human skin, approximated as a self-affine fractal. It should be noted, however, that apart from experimental evidence, the difficulties in solving the coupled fluid and elastic equations have led to widespread use of finite element models and simulations. Their clear advantage is being able to include numerous terms that would be analytically intractable; their disadvantage is a corresponding difficulty in capturing the essential physics through admittedly very rough approximations to the cases of interest. It was our intent here to obtain analytic solutions to Stokes lubrication coupled to a highly simplified constitutive law for the elastic boundary, and in particular one that may be relevant to the sliding of the lung against the chest wall. Our results illuminate salient features of velocity dependence of friction in the sliding of soft surfaces against one another, and show how these may be viewed in a unified manner.

In both the sharply pointed rigid V block and the smooth rigid Q block, we see a close approximation to Coulomb-type friction, in the sense of an unbounded rise in rate of change of the friction coefficient with U , as U →0 . Specifically, the V block shows a discontinuity in FT / FN at U* = 0 (Eq. (10), Fig. 2). This is true starting friction, and moreover its value depends only on the geometry of the surface and not on FN. The smooth rigid Q block does not show a discontinuity at U = 0 , but approximates this behavior with a square root singularity in FT / FN at U =0.

The rigid blocks suffer from the fact that there is a solution for nonnegative FN only for U ≥ 0 ; these models are clearly inadequate to deal with net load support in reciprocating motion such as the breathing cycle. This is overcome in the elastic models, since the sign of the asymmetry ξ is the same as that of FT and hence the same as U . The elastic cases also show a similar degree of approximation to Coulomb friction. The elastic V block still shows a nonzero starting friction (albeit with a magnitude that actually, and curiously, decreases with FN), and the Q block has a cube root singularity in FT / FN at U = 0.

The physics behind the nonzero starting friction with the V block is traceable to the fact that the divergences in of both the tangential and normal forces as the gap thickness decreases are of the same order (in this case logarithmic, Eq. (9)). This in turn is associated with the sharpness of the wedge edge. For a fixed degree of asymmetry in the rigid V block, this is intuitive, but it is surprising that the same feature of a nonzero starting friction should also obtain in the elastic V block case, where the undeformed block is symmetric (ξ = 0), but the block remains deformed (ξ is bounded away from 0) even in the limit as U*→0. None of these observations carries through for the smooth Q block, because the divergences in Eqs. (15) as D0→0 are of different order. In particular, the divergence of the tangential force () is milder than that of the normal force (), and so the friction coefficient tends to zero as velocity (and hence D0) approaches zero. Nevertheless, the general feature of an approximate starting frictional characteristic remains.

It should be noted that what we are describing as starting friction in the V block case (and its approximation in the smooth Q block case) is of purely hydrodynamic origin. The physics of actual starting friction involves significantly more complex phenomena, including actual contact forces that need to be overcome. Indeed, it is widely observed that such starting friction or “stiction” is in general higher than the subsequent friction during sliding, contrary to our results. Such mechanisms are no doubt important in many applications, but are beyond the scope of our analysis, where we have chosen to restrict attention to the hydrodynamic component of the interaction.

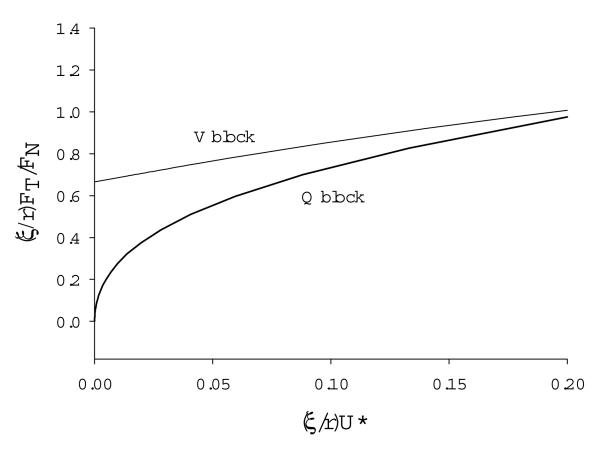

With respect to universality, we note that while typical tribological data are displayed as friction coefficients versus a normalized velocity (e.g. the Sommerfeld parameter), this leads to a number of families of possible behaviors, depending on surface roughness and degree of asymmetry (either independently given in the rigid case or dependently conditional on the tangential force developed and some measure of material stiffness). However, inspection of Eqs. (7) and (8) for the V block shows that the functions (ξ / r) fT / fN and (ξ / r)U * are only functions of D0. This implies that there is a universal relationship of friction and velocity for the V block, either rigid or elastic, which is independent of surface geometry and material stiffness. Similarly, from Eqs. (7) and (14), a universal relationship also exists for the Q block. These are both shown in Fig. 5. For rigid blocks, this figure can be used directly for any given set of surface geometry parameters. For elastic blocks, this figure must be coupled with the requirement that the degree of asymmetry satisfy the constitutive law in Eq. (12). This can be done numerically or even graphically, noting that the constitutive law is equivalent to

| (19) |

In this form, the elastic condition can be plotted on the same axes as Fig. 5; it is a simple homogeneous quadratic function of ξU * / r , with a prefactor that depends on the stiffness of the material. The intersection of this quadratic with the curve (V or Q as appropriate) in Fig. 5 then represents the elastic solution. It would be interesting to see if some estimates of asymmetry and roughness in other tribological data would tend to collapse the data as suggested here.

Fig. 5.

Coefficient of sliding friction FT / FN versus normalized velocity, U* = μU / rFN, each axis scaled by the ratio of geometric asymmetry ξ to surface roughness r . This scaling reduces all data, for both rigid and elastic materials, to universal curves. Light line: V block, bold line: Q block.

While the analysis presented in this paper is strictly limited to steady state sliding, the ideas here may be important in reciprocating motion that is slow enough to ensure quasi-steady state Stokes flow. Our particular interest is in the lung sliding against the chest wall during periodic breathing. Our results suggest that shear stress would deform surface unevenness in a way that increases lift, thereby separating regions that might otherwise come in contact. This elastic deformation will always favor lift generation, a requirement for effective lubrication with reciprocating motion such as that of the lungs, heart, joints, and eyes. To the extent that the lung or chest wall has, on microscopic length scales, effectively sharp V shaped features, there will be a contribution to a quasi-static hysteretic behavior in the relationship between sliding velocities and the induced shear stresses. By contrast, smooth features behaving like the elastic Q block would exhibit no such quasi-static hysteresis. This difference may be unimportant if there is insufficient time to achieve the steady state during reversals of sliding direction. Time scales for fluid redistribution in the face of pleural pressure gradients [7] at present are not well known. Nevertheless, this analysis is relevant to the mechanisms that govern the fluid dynamics of the pleural space. D’Angelo et al. [5] have recently found that sinusoidal sliding of freshly excised and wetted rabbit mesothelial tissues exhibit coefficients of friction that are not dependent on sliding velocity, consistent with Coulomb-like friction. Subsequent studies [6] also show weak velocity dependences, albeit in a limited range of low sliding velocities. This behavior has been conventionally attributed to boundary lubrication, in which shear forces are due to contact and deformation of the asperities of the sliding surfaces, and there is no significant hydrodynamic separation of these surfaces by lubricant. By contrast, the strictly hydrodynamic mechanism proposed here may provide an alternate explanation for Coulomb-like behavior without points of contact between apposed tissue surfaces, and importantly, load supporting in both phases of reciprocation motion.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge very helpful advice from Prof. T.J. Pedley, and continual and persistent encouragement from Dr. R.E. Brown. JPB thanks Prof. H. Sasaki and the support of the Japanese Foundation for Aging and Health. This work supported in part by NHLBI grant HL 63737.

Appendix

There are five integrals associated with any given dimensionless shape function D(w). Using the bracket notation , there are four are needed in Eq. (6), < D−1 > , < D−2 > , < wD−2 > , and < wD−3 >. For volume flow rates, < D−3 > is also needed. We include all five here for completeness.

For the V block, the shape is given by D(w) = D0 + w , and the relevant integrals are given by

| (A1) |

| (A2) |

For the Q block, the shape is given by D(w) = D0 + w2 , and we have

| (A3) |

| (A4) |

where .

Nomenclature

| Dimensional quantities |

Non-dimensional quantities |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| L | half (axial) length of the solid block | |

| P | pressure | |

| μ | fluid viscosity | |

| Φ | material modulus of rigidity | |

| U | U* = μU / rFN | sliding velocity of the bottom surface |

| Q | volume flow rate | |

| x∈[−L, L] | w∈[0,1] | axial coordinate (w defined separately on each segment |

| d ≡ d(x), d0 | D = d / δ, D0 | channel height, minimum channel height |

| δ | variation in channel height, max(d) – min(d) | |

| r = δ / 2L | surface “roughness” | |

| ξ | degree of surface asymmetry | |

| FN | fN = FN / 6μU | net normal force |

| FT | fT = FT / 6μU | net tangential force (on bottom surface) |

References

- [1].Agostoni E, D’Angelo E. Pleural Liquid Pressure. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71(2):393–403. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lai-Fook SJ. Pleural Mechanics and Fluid Exchange. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(2):385–410. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lai-Fook SJ. Mechanics of the Pleural Space: Fundamental Concepts. Lung. 1987;165(5):249–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02714442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].D’Angelo E. Stress-Strain Relationships During Uniform and Non Uniform Expansion of Isolated Lungs. Respir Physiol. 1975;23(1):87–107. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(75)90074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].D’Angelo E, Loring SH, Gioia ME, Pecchiari M, Moscheni C. Friction and Lubrication of Pleural Tissues. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;142(1):55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Loring SH, Brown RE, Gouldstone A, Butler JP. Lubrication Regimes in Mesothelial Sliding. J Biomech. 2005;38(12):2390–2396. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Butler JP, Huang J, Loring SH, Lai-Fook SJ, Wang PM, Wilson TA. Model for a Pump That Drives Circulation of Pleural Fluid. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78(1):23–29. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gouldstone A, Brown RE, Butler JP, Loring SH. Elastohydrodynamic Separation of Pleural Surfaces During Breathing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;137(1):97–106. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lai J, Gouldstone A, Butler JP, Federspiel WJ, Loring SH. Relative Motion of Lung and Chest wall Promotes Uniform Pleural Space Thickness. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2002;131(3):233–243. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(02)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Moghani T, Butler JP, Lin JL, Loring SH. Finite Element Simulation of Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication of Soft Biological Tissues. Comput Struct. 2007;85:1114–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruc.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Batchelor GK. An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1967. pp. 219–222. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Skotheim JM, Mahadevan L. Soft Lubrication: The Elastohydrodynamics of Nonconforming and Conforming Contacts. Physics of Fluids. 2005;17(9):092101. http://scitation.aip.org.

- [13].Dowson D. Transition to Boundary Lubrication From Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication. In: Ling EFK, E.E., Flein RS, editors. Boundary Lubrication: An Appraisal of World Literature. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers; New York: 1969. pp. 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Miserocchi G, Agostoni E. Contents of the Pleural Space. J Appl Physiol. 1971;30(2):208–213. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.30.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hills BA, Butler BD, Barrow RE. Boundary Lubrication Imparted by Pleural Surfactants and Their Identification. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53(2):463–469. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.2.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hills BA. Graphite-Like Lubrication of Mesothelium by Oligolamellar Pleural Surfactant. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73(3):1034–1039. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.3.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Davies MG. The Generation of Lift by Surface Roughness in a Radial Face Seal. Int. Conf. on Fluid Sealing; Essex, England. 1961. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gabelli A, Poll G. Formation of Lubricant Film in Rotary Sealing Contacts: Part I--Lubricant Film Modeling. Journal of Tribology. 1992;114:280–289. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Salant F. Modeling Rotary Lip Seals. Wear. 1997;207:92–99. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shi F, Salant RF. A Mixed Soft Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication Model with Interasperity Cavitation and Surface Shear Deformation. Journal of Tribology. 2000;122:308–316. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rodkiewicz CM, Sinha P. On the Lubrication Theory: A Mechanism Responsible for Generation of the Parallel Bearing Load Capacity. Journal of Tribology. 1993;115:584–590. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jin ZM, Dowson D. Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication in Biological Systems. J Engineering Tribology. 2005;211:367–380. Proc. ImechE Vol. 219 Part J. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gong JP. Friction and Lubrication of Hydrogels--Its Richness and Complexity. Soft Matter. 2006;2:544–552. doi: 10.1039/b603209p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sayles RS, Lee-Prudhoe I, Bouvet C. Some Aspects of the Contact Mechanics and Lubrication of Low Modulus Materials in Rough Interfaces. Elastohydrodynamics ‘96 Fundamentals and Applications in Lubrication and Traction. 1997;32:209–217. [Google Scholar]