Abstract

Of the 33 million people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) worldwide, 40–60% of individuals will eventually develop neurocognitive sequelae that can be attributed to the presence of HIV-1 in the central nervous system (CNS) and its associated neuroinflammation despite antiretroviral therapy. PrPC (protease resistant protein, cellular isoform) is the nonpathological cellular isoform of the human prion protein that participates in many physiological processes that are disrupted during HIV-1 infection. However, its role in HIV-1 CNS disease is unknown. We demonstrate that PrPC is significantly increased in both the CNS of HIV-1–infected individuals with neurocognitive impairment and in SIV-infected macaques with encephalitis. PrPC is released into the cerebrospinal fluid, and its levels correlate with CNS compromise, suggesting it is a biomarker of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. We show that the chemokine (c-c Motif) Ligand-2 (CCL2) increases PrPC release from CNS cells, while HIV-1 infection alters PrPC release from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Soluble PrPC mediates neuroinflammation by inducing astrocyte production of both CCL2 and interleukin 6. This report presents the first evidence that PrPC dysregulation occurs in cognitively impaired HIV-1–infected individuals and that PrPC participates in the pathogenesis of HIV-1–associated CNS disease.

Approximately 33 million people are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) worldwide.1 Despite antiretroviral therapy, 40–60% of infected individuals develop neurocognitive sequelae that can be attributed to the presence of HIV-1 in the central nervous system (CNS) and its associated neuroinflammation.2 HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) represents a spectrum of disease ranging from subclinical to severe cognitive impairment.3 HAND is a significant morbidity among HIV-1–infected individuals4,5 and is increasingly presenting as an AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome)-defining illness.6,7

PrPC (protease resistant protein, cellular isoform) is the nonpathological cellular isoform of the human prion protein. It is most abundantly expressed in the CNS, where it is found constitutively on CNS cells,8,9 the BBB,10,11 and on infiltrating leukocytes.11,12 PrPC localizes to the cell membrane, where it is anchored by glycosylphosphatidylinositol13 and functions as both an adhesion molecule14–18 and transducer of intracellular signaling.17,19–21 Importantly, PrPC plays a role in many of the physiological processes disrupted during HIV-1 infection. In the CNS these include monocyte transmigration across the BBB,16 macrophage phagocytosis,22 leukocyte21,23 and microglia activation,24 cellular taxis,22 glutamate metabolism,25 neuronal synaptic plasticity,15,17 and NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartic acid) receptor-associated calcium signaling.26 We therefore hypothesized that HIV-1 infection, and/or its associated neuroinflammation, dysregulate PrPC, thereby contributing to the cognitive impairment observed in HIV-1–infected individuals.

We compared CNS PrPC expression in HIV-1–infected individuals with and without cognitive impairment to uninfected individuals and evaluated its soluble form as a potential biomarker of CNS dysfunction. We used the pigtail macaque model of neuroAIDS to investigate alterations in PrPC during defined stages of an accelerated disease process. We found PrPC is increased significantly in the brain of HIV-1–infected individuals with neurocognitive impairment, relative to infected and uninfected individuals who are unimpaired, and in SIV-infected macaques with encephalitis, as compared to infected and uninfected animals without encephalitis. We found that elevated soluble PrPC (sPrPC) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels predict neurocognitive impairment in HIV-1–infected individuals, suggesting that CSF sPrPC is a biomarker of HAND. We also showed that sPrPC in the CSF reflects the extent of encephalitis in SIV-infected macaques. We demonstrated that CCL2, a chemokine that is elevated in the CNS of individuals with HAND and is associated with neuropathology,27,28 significantly increases PrPC release from CNS cells and that HIV-1 infection alters the release of PrPC from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. We also showed that sPrPC contributes to neuroinflammation by increasing the production of CCL2 and interleukin (IL)-6 by astrocytes. This is the first demonstration of PrPC dysregulation in neurocognitively impaired individuals infected with HIV-1.

Materials and Methods

Human Tissue, CSF, and Sera

Tissue was collected as part of the IRB-approved protocols of the Manhattan HIV Brain Bank. Research subjects undergo a rigorous battery of neuropsychological, neuromedical, and psychiatric assessments, as described previously,29 and blood is evaluated for viral load and CD4 T-cell counts. Cognitive diagnoses are rendered by two systems. We operationalized American Academy of Neurology criteria for diagnoses of HIV-associated dementia and minor cognitive motor disorder.30 Cerebral cortex was evaluated from four seronegative individuals without cognitive impairment, two HIV-1–infected individuals without cognitive impairment, four HIV-1–infected individuals with minor motor cognitive disorder (MCMD), two individuals with HIV-associated dementia (HAD), and two individuals with HIV encephalitis (HIVE). We also examined tissue from underlying white matter obtained from the same individuals described above with similar results (data not shown). CSF samples were evaluated from five uninfected individuals who are unimpaired, five HIV-1–infected individuals with MCMD, and five HIV-1–infected individuals with HAD. Sera samples were evaluated from three uninfected individuals without cognitive impairment, three uninfected individuals with neurocognitive impairment, five HIV-1–infected individuals without cognitive impairment, five HIV-1 seropositive individuals with MCMD, and five HIV-1–infected individuals with HAD (see details in Table 1).

Table 1.

Elevated Expression of CNS PrPC Is Independent of Age, Gender, Race, Peripheral Viral Load, and CD4 T-Cell Count

| Age (years) | Sex (male/female) | Race | Peripheral viral load (copies/ml) | Peripheral CD4 count (cells/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV (−) | 57 | F | W | NA | NA |

| HIV (−) | 58 | F | H | NA | NA |

| HIV (−) | 48 | M | B | NA | NA |

| HIV (−) | 50 | M | H | NA | NA |

| HIV (+) | 46 | M | W | Undetectable | 233 |

| normal | |||||

| HIV (+) | 49 | M | W | Undetectable | 103 |

| normal | |||||

| HIV (+) | 58 | M | B | Undetectable | 204 |

| MCMD | |||||

| HIV (+) | 58 | F | B | 576,000 | 98 |

| MCMD | |||||

| HIV (+) | 28 | M | A | 2097 | 5 |

| MCMD | |||||

| HIV (+) | 50 | M | W | 26,621 | 20 |

| MCMD | |||||

| HIV (+) | 49 | M | B | 1521 | 215 |

| HAD | |||||

| HIV (+) | 51 | M | H | 65 | 136 |

| HAD | |||||

| HIV (+) | 44 | M | W | 389,120 | 7 |

| HIVE | |||||

| HIV (+) | 47 | M | B | 367,620 | 2 |

| HIVE |

Demographics of individuals from which cerebral cortex tissue sections were evaluated for PrPC expression by immunohistochemistry. MCMD indicates minor motor cognitive disorder; HAD, HIV-associated dementia; HIVE, HIV encephalitis; F, female; M, male; W, white/Caucasian; H, Hispanic; B, black/African American; A, Asian; NA, not applicable and not assessed.

Pigtail Macaque Infection, Tissue Evaluation, and Fluid Collection

Pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) were dual-inoculated intravenously with a virus swarm, SIV/DeltaB670, and with the molecular clone SIV/17E-Fr.31,32 Three negative control animals were mock-inoculated. After inoculation, blood and CSF were collected weekly for the first six weeks, then biweekly for quantification of viral RNA and inflammatory proteins including CCL2. Animals with mild encephalitis had low RNA viral copy numbers and low CCL2, while those with severe encephalitis had high viremia and high CCL2.33–35 The animals were euthanized at 3 months postinoculation and complete necropsies were performed. All CNS tissues were microscopically examined by two pathologists and scored independently for the severity of the observed lesions.31,32 CNS tissue was evaluated from two uninfected animals, one SIV-infected animal without encephalitis, three SIV-infected animals with mild encephalitis, and three SIV-infected animals with severe encephalitis. CSF obtained from six uninfected animals without encephalitis, five SIV-infected animals with mild encephalitis, and five SIV-infected animals with severe encephalitis were evaluated. Plasma from three uninfected animals without encephalitis, three SIV-infected individuals without encephalitis, five SIV-infected animals with mild encephalitis, and five SIV-infected animals with severe encephalitis were also evaluated.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections of cerebral cortex and underlying white matter were obtained at autopsy/necropsy, processed, embedded in paraffin, and affixed onto slides. The postmortem intervals with the exception of one HAD case were from 5 to 24 hours, with no significant differences between groups. Human samples were processed at the Manhattan HIV Brain Bank and simian tissue was processed at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine as previously described.31 Before immunostaining, tissue sections were deparaffinized with ethanol and xylene and washed in Tris-buffered saline. Triton antigen retrieval was then performed. Tissue was incubated in blocking solution (5 mmol/L EDTA, 1% fish gelatin, 1% essentially Ig-free BSA, and 2% horse serum) overnight at room temperature. Proteins were labeled with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: MAP-2 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), CD68 (Santa Cruz, CA), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and PrPC (Clone SAF-32, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Tissue was also incubated with an equal concentration of the following species or isotype-matched antibodies as a control: rabbit IgG, goat IgG, and mouse IgG2b (all from Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). After washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), tissue was incubated in the following fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature: sheep anti-mouse IgG-FITC, rabbit anti-goat IgG-Cy3, goat anti-rabbit IgG- Cy3, (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or donkey anti-mouse IgG-Cy5 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Tissue was again washed in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by mounting with Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Molecular Probes, Junction City, OR). Tissue sections were imaged at ×40 magnification using a Leica AOBS laser scanning confocal microscope and its accompanying software. Antibody specificity was verified and nonspecific background immunofluorescence was detected using isotype- or species-matched control antibodies and was minimal in all experiments. Quantification of the PrPC staining in cortex as well as underlying white matter tissue sections of humans was performed using NIS Elements Advanced Research software (Nikon, Japan) to determine the total and the mean intensity of fluorescence in the PrPC channel. The background obtained with the respective irrelevant antibodies was subtracted before the analyses.

Primary Human Neuron and Astrocyte Cultures

Primary human neurons and astrocytes were obtained as part of an ongoing research protocol at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and were cultured as previously described.36,37 For neuron enrichment, mixed cultures of neurons and astrocytes were plated at a density of 9 × 107 in DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1% nonessential amino acids (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), and 2% HEPES (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH). To enrich for astrocytes, mixed cultures of neurons and astrocytes were plated at a density of 4.5 × 107 in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% nonessential amino acids (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and 2% HEPES (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH). After one week in culture, cells were dissociated and replated. To propagate pure neuron cultures, cells from the neuron-enriched flasks were plated onto 100-mm culture dishes coated with 0.005% poly-D-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in neurobasal media supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1 bottle of N-2 supplement (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Media was changed every 2–3 days until pure neuron cultures were obtained. Pure astrocyte cultures were propagated by plating directly onto plastic 100-mm culture dishes in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Neuron/astrocyte cocultures were propagated by plating directly onto plastic 100-mm culture dishes and growing in neurobasal media supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1 bottle of N-2 supplement (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and 0.5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). Experiments with pure neuron cultures and neuron/astrocyte cocultures were conducted 6–8 days after being plated onto 100-mm culture dishes. Pure astrocyte cultures were passaged once before conducting experiments.

Primary Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell Cultures

Primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells were obtained from Applied Cell Biology Research Institute (Kirkland, WA) and cultured as previously described.36 Cells were grown to confluence on 0.2% gelatin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA)-coated 100 mm tissue culture dishes in M199 media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated newborn calf serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 5% heat-inactivated human serum type AB (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 0.8% l-glutamine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 0.1% heparin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.1% ascorbic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.25% endothelial cell growth supplement (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 0.06% bovine brain extract (Clonetics, Walkersville, MD).

Primary Human Monocyte, Macrophage, and PBMC Isolation and Culture

Human blood from healthy volunteers was obtained from the New York Blood Center and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Ficoll-Paque (GE Health care, Uppsala, Sweden). PBMCs were grown in suspension at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml in 5 ml of 1640 RPMI media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), 1% HEPES (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Cells were activated for 2 days before experimentation by adding 5 μg/ml PHA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 10 ng/ml IL-2 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Monocytes were isolated from PBMCs using CD14 magnetic beads and columns according to manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Monocytes were grown in suspension at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml in 5 ml of 1640 RPMI media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human serum type AB and 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), 1% HEPES (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and 10 ng/ml M-CSF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Monocytes were grown in polypropylene tubes (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) to avoid adherence to plastic and differentiation into macrophages. For studies with macrophages, CD14-isolated cells were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml in 4 ml 1640 RPMI media (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 5% heat-inactivated human serum type AB (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), 1% HEPES (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and 10 ng/ml M-CSF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) onto 60 mm tissue culture dishes to facilitate adherence. Media was changed every 3 days.

CCL2 Treatment

Twenty-four hours before treatment of neurons, astrocytes, neurons/astrocytes, and human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMVECs), cell media was replaced with 3 ml of fresh media. For CCL2 treatment of cell cultures, human recombinant CCL2/MCP-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added directly to cell culture media to a final concentration of 200 ng/ml. Control cultures were treated with an equal volume of 0.1% BSA in PBS, the CCL2 diluent.

Transfer of Astrocyte Supernatant onto Neurons

Twenty-four hours before media transfer, astrocyte media was changed from supplemented DMEM to 3 ml of supplemented neurobasal. Six hours in advance of media transfer, CCL2, or an equal volume of 0.1% BSA in PBS, was added to astrocyte cultures at a final volume 200 ng/ml. At time of transfer, media from astrocyte cultures was removed and saved for analysis of sPrPC levels by ELISA. Media from astrocytes was then transferred to the neuron cultures, with media from a replicate neuron plate saved for sPrPC evaluation. After 30 minutes, 2 hours, 6 hours, or 24 hours, media was removed from neuron cultures and evaluated by ELISA.

HIV-1 Infection

Monocytes were infected after 3 days in culture, while macrophages were infected after 6–7 days in culture. Both cell types were infected with 20 ng/ml of the R5-tropic strain HIV-1ADA generated in CEM-SS cells (NIH repository, Germantown, MA). After 24 hours, virus was washed from the cultures and fresh media was added. Supernatants were collected and viral replication was assessed by HIV-p24 ELISA according to manufacturer's instructions (Advanced BioScience Laboratories, Kensington, MD).

Treatment of Astrocyte Cultures with Recombinant Human PrPC

Astrocytes were grown in DMEM-supplemented media on 96-well tissue culture plates for 2 days. Full length human recombinant PrPC (Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany) was added to fresh media at a final concentration of 0.45 μmol/L. Media was aspirated from wells and 200 μl of PrPC-supplemented media was then added to each well. Negative control plates received fresh media with an equal concentration of diluent. Positive control plates were treated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β to verify astrocyte response to stimulation. After 6 hours, media was collected from each plate.

ELISA

Sera/plasma and CSF were diluted in buffer and evaluated by PrPC ELISA (SPI-Bio, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France).11 A standard curve was generated from PrPC standard supplied in the kit and protein concentration was determined by an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). The limit of detection of the assay was 0.3 ng/ml. A DuoSet ELISA was used to evaluate CCL2 levels in human CSF according to manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The limit of detection of this assay was 9.38 pg/ml. To evaluate released PrPC from cultures of neurons, astrocytes, neuron/astrocyte cocultures, and HBMVCs, media was removed from cultures and stored at 4°C while cell viability of cultures was evaluated by trypan blue staining. Briefly, cells were removed from culture dishes using trypsin/EDTA (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), pelleted by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes, diluted in trypan blue (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and evaluated for cell viability using a light microscope. If cultures were found to be free of dead or dying cells, collected media was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C followed by ultracentrifugation at 13,300 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet cellular debris. Supernatant was then collected. For each treatment condition (CCL2 or vehicle) experiments were performed in five replicates. Three milliliters of media was collected from each of the five plates. After ultracentrifugation to remove cell debris, supernatants from each of the five replicates (15 ml total) were pooled and concentrated to 250 μl using an Amicon Ultra-15, 10k filter centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Bellerica, MA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Fifteen milliliters of media was also concentrated to the same volume to control for soluble protein present in the sera component of the supplemented media. For determination of PrPC released from macrophage cultures, 4 ml of media was collected from one culture dish and was centrifuged and concentrated as described above. Similarly, for sPrPC determination from monocyte and PBMC suspensions, cells were first pelleted before media was removed. Cells were counted and sPrPC levels were normalized to number of live cells in culture. To evaluate inflammatory factors released from full-length human recombinant PrPC-treated astrocytes, media was collected from each plate and concentrated to a final volume of 250 μl using an Amicon Ultra-15, 10k filter centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Bellerica, MA) according to manufacturer's instructions. CCL2/MCP-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 production by astrocytes was evaluated by DuoSet ELISA according to manufacturer's instructions (all from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The limits of detection of these kits are 9.38 pg/ml for CCL2, 9.38 pg/ml for IL-6, 15.63 pg/ml for TNF-α, and 31.25 pg/ml for MMP-9.

Data Analysis

Statistics were obtained using a Student's two-tailed paired t-test. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05. All data were reproducible in at least three independent experiments.

Results

PrPC Is Increased in the Brain of HIV-1–Infected Individuals with Neurocognitive Impairment

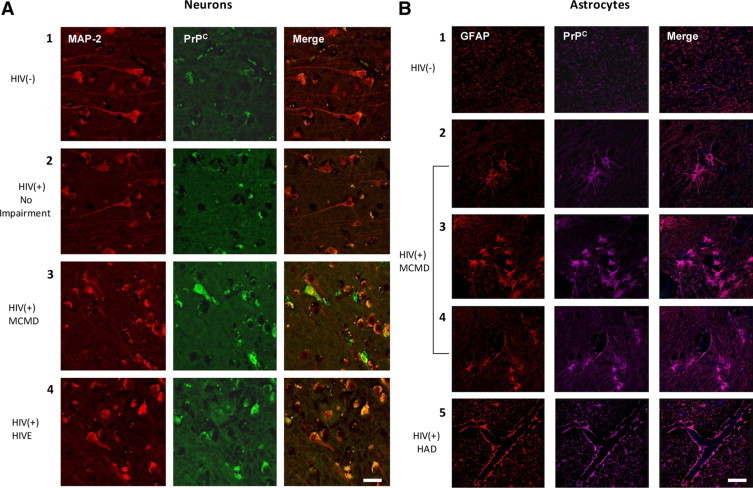

PrPC is constitutively expressed in the CNS8,9; however, no studies examined PrPC in the HIV-1–infected brain. We therefore used immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy to compare PrPC expression in the brain of HIV-1–infected individuals with and without neurocognitive impairment to that of uninfected individuals (Figure 1). Neuronal PrPC was evaluated by examining colocalization of PrPC (FITC-green) with MAP2 (Cy3-red), a neuron-specific microtubule-associated protein (Figure 1A). Neuronal PrPC is increased in the brain of HIV-1–infected individuals with minor motor cognitive disorder/MCMD (Figure 1A, panel 3) and HIV encephalitis/HIVE (Figure 1A, panel 4) relative to uninfected individuals (Figure 1A, panel 1) and HIV-1–infected individuals who are unimpaired (Figure 1A, panel 2). The astrocyte-specific intermediate filament glial fibrillary acid protein GFAP (Cy3-red) was used to evaluate astrocyte PrPC (Cy5-magenta) expression (Figure 1B). Astrocytes with HIV-associated morphological changes including hypertrophy (Figure 1B, panel 2), proliferation (Figure 1B, panel 3), and extensive process formation (Figure 1B, panel 4) have elevated PrPC in individuals with MCMD when compared to uninfected individuals (Figure 1B, panel 1). Astrocyte PrPC is also increased at the BBB, where astrocyte foot processes contact the endothelium in individuals with HIV-associated dementia/HAD (Figure 1B, panel 5), relative to uninfected individuals (Figure 1B, panel 1). The significant elevation of PrPC in HIV-1–infected individuals with neurocognitive impairment was independent of age, gender, race, peripheral viral load, and CD4 T-cell counts in this patient population (Table 1). All cases from the same condition had similar staining patterns as the representative pictures shown in Figure 1. These data indicate that CNS PrPC increases with neurocognitive impairment in HIV-1–infected individuals.

Figure 1.

PrPC is increased significantly in the brain of individuals with HIV-1-associated neurocognitive impairment. Frontal cerebral cortex was obtained at time of autopsy from individuals who were HIV negative, unimpaired (HIV−), n = 4; HIV-infected, unimpaired (HIV+), n = 2; HIV-infected with minor motor cognitive disorder (MCMD), n = 4; HIV-infected with HIV-associated dementia (HAD), n = 2; and HIV-infected with HIV encephalitis (HIVE), n = 2. Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue sections and was imaged using confocal microscopy. A: Neuronal expression of PrPC (FITC-green) was evaluated using MAP-2 (Cy3-red; neuronal marker). PrPC was increased in individuals with MCMD and HIVE relative to uninfected (panel 1) and infected individuals (panel 2) who were unimpaired. B: Astrocyte expression of PrPC was indicated by GFAP (Cy3-red; astrocytic marker) and PrPC (Cy5-magenta) colocalization. PrPC expression was elevated in astrocytes showing HIV-mediated pathology including hypertrophy (panel 2), proliferation (panel 3), and extensive process formation (panel 4) in individuals with HAD as compared to uninfected individuals (panel 1). Astrocyte PrPC was also increased at the blood–brain barrier where astrocyte foot processes contact the endothelium in individuals with HAD (panel 5), relative to levels in uninfected individuals (panel 1). PrPC was consistently expressed in all tissues.

Quantification of the total fluorescence and the mean fluorescence intensity of PrPC staining obtained from human tissue sections was performed using NIS Elements Advance Research software (Nikon, Japan). The results indicate that control normal brain sections have a total intensity of PrPC staining of 656,748.06 ± 324,481.31 arbitrary units (A.U.) with a mean intensity of 4.24 ± 2.65 A.U. HIV-infected brains without impairment have a total intensity of PrPC staining of 1469,213.91 ± 101,655 A.U. with a mean intensity of 9.58 ± 2.98 A.U. HIV-infected brains with MCMD have a total intensity of PrPC staining of 3066,994 ± 639,229 A.U. with a mean intensity of 14.63 ± 6.13 A.U. Lastly, HIV tissue sections with HAD and HIVE have a total intensity of PrPC staining of 1937,712 ± 222,975 A.U. with a mean intensity of 10.68 ± 4.1 A.U. These results indicate that HIV(+) no impairment, HIV(+) MCMD, and HIV(+)HIVE/HAD were significantly different from control sections of uninfected unimpaired individuals in total and mean fluorescence and that MCMD and HIVE/HAD sections had more PrPC staining than those obtained from HIV-infected unimpaired individuals. The data are control versus HIV(+) no impairment, P = 1.76 × 10−34 and P = 1.51 × 10−11, respectively, control versus HIV(+)MCMD, P = 2.54 × 10−30 and P = 1.46 × 10−17, respectively, control versus HIV(+) HIVE/HAD, P = 1.46 × 10−54 and P = 4.62 × 10−19, respectively. For HIV(+) unimpaired versus HIV(+)MCMD, P = 7.8 × 10−25 and P = 2.6 × 10−6, respectively. For HIV(+)MCMD versus HIVE/HAD, P = 2.85 × 10−18 and P = 0.00011, respectively. For HIV(+) unimpaired versus HIV(+)HIVE/HAD, P = 5.5 × 10−25 and P = 0.139, respectively. The numbers of tissue sections are indicated in Table 1, and the numbers of confocal pictures analyzed for conditions were 71 pictures for controls, 31 pictures for HIV(+) no impairment, 53 pictures for HIV(+) MCMD, and 65 pictures of HIV (+) HIVE/HAD. No differences were founded between HIVE and HAD tissue sections.38 Isotype-matched control antibodies were negative and were used as background controls for the quantification of fluorescence (data not shown).

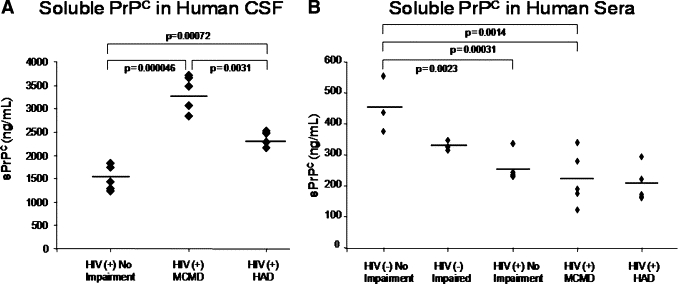

Soluble PrPC Is Selectively Elevated in the CSF of Individuals with HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Impairment

We determined that PrPC is dysregulated in HIV CNS tissue and that tissue from individuals with HAND had significantly higher fluorescence intensities than did sections from HIV-infected people without impairment or uninfected individuals. sPrPC has been reported in the CSF and sera/plasma of individuals with other neuroinflammatory and neurocognitive disorders.11,39,40 However, no studies have examined sPrPC in individuals infected with HIV. We therefore used ELISA to determine whether release of PrPC into the CSF or sera is associated with neurocognitive impairment in HIV-1–infected individuals. We found CSF sPrPC levels to be elevated in HIV-1–infected individuals with HAND (MCMD and HAD) as compared to HIV-1–infected individuals who are unimpaired (Figure 2A). These findings are independent of CNS viral load and peripheral CD4 T-cell count but do correlate with CNS CCL2 levels (Table 2), an indicator of neuroinflammation.41 This suggests that CCL2 plays a role in PrPC release. Interestingly, CSF sPrPC levels were significantly higher in individuals with MCMD than with HAD. We propose that this may be due to neuronal dropout in HAD as we recently reported,42 reducing a potentially important source of sPrPC.

Figure 2.

CSF soluble PrPC levels predict neurocognitive impairment in HIV-1–infected individuals. CSF was obtained from individuals diagnosed as HIV-1–infected, neurocognitively normal; HIV-1–infected with minor motor cognitive disorder (MCMD); HIV-1–infected with HIV-associated dementia (HAD); uninfected, neurocognitively normal; and uninfected with neuropsychiatric impairment. Soluble PrPC (sPrPC) was evaluated by ELISA. A: CSF levels of sPrPC were elevated in individuals with HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment (MCMD and HAD) relative to infected individuals without neurocognitive impairment. Individuals with MCMD had higher CSF sPrPC levels than those with HAD, likely due to loss of neuropil. Soluble PrPC mean values: 1500.98 ng/ml (HIV-1–infected, unimpaired); 3348.07 ng/ml (HIV-1–infected, MCMD); 2372.81 ng/ml (HIV-1–infected, HAD). B: Sera was obtained from uninfected, unimpaired individuals; uninfected, neurocognitively impaired individuals; HIV-1–infected, unimpaired individuals; HIV-1–infected individuals with MCMD; and HIV-1–infected individuals with HAD, and was evaluated for sPrPC by ELISA. Neurocognitively unimpaired and impaired individuals who were infected with HIV-1 had lower levels of sPrPC in their sera than uninfected individuals. However, there was no difference in sera sPrPC among HIV-1–infected individuals who were cognitively normal or cognitively impaired. Thus CSF but not sera sPrPC may be a specific biomarker of neurocognitive impairment and CNS dysfunction in individuals with HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. Soluble PrPC mean values: 455.33 ng/ml (uninfected, unimpaired); 329.08 ng/ml (uninfected, neurocognitively impaired); 254.81 ng/ml (HIV-1–infected, unimpaired); 220.92 ng/ml (HIV-1–infected, MCMD); and 202.70 ng/ml (HIV-1–infected, HAD).

Table 2.

Comparison of CSF Soluble PrPC, Viral Load, and CCL2 Levels with Peripheral CD4 Count

| CSF sPrPC (ng/ml) | CSF viral load (copies/ml) | CSF CCL2 (pg/ml) | Peripheral CD4 count (cells/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV (+) Normal (n = 5) | Mean: 1500.98 Range: (1231–1825) | Range: (19,530-undetectable) | Mean: 110.08 Range: (37.64–147.05) | Mean: 477.8 Range: (188–1068) |

| HIV (+) MCMD (n = 5) | Mean: 3348.07 Range: (2844–3718) | Range: (100,000-undetectable) | Mean: 530.17 Range: (319.14–697.32) | Mean: 267.8 Range: (36–552) |

| HIV (+) HAD (n = 5) | Mean: 2372.81 Range: (2155–2508) | Range: (undetectable) | Mean: 413.66 Range: (289.67–534.37) | Mean: 326.4 Range: (126–721) |

CSF obtained from HIV-1–infected individuals without neurocognitive impairment and from those with MCMD and HAD was evaluated for sPrPC, HIV-1 viral load, and CCL2. Peripheral CD4 T-cell counts were also evaluated. CSF sPrPC does not correlate with CSF viral load or with level of peripheral immunosuppression. CSF sPrPC does, however, correspond positively with CSF CCL2.

When the sera of HIV-1–infected individuals were evaluated, sPrPC levels were significantly decreased relative to uninfected individuals (Figure 2B). However, there was no statistical difference in sPrPC levels among HIV-1–infected individuals with and without neurocognitive impairment. Thus, sera sPrPC is not a predictor of HAND. There was also no direct correlation between peripheral and CNS sPrPC levels (data not shown). CSF sPrPC levels were five- to 10-fold higher than sera levels, suggesting substantial PrPC release in the HIV-1–infected CNS (not shown). Collectively, these findings indicate that CSF, but not sera, sPrPC levels are predictive of HAND. Therefore, CSF sPrPC may be a biomarker of neurocognitive impairment in HIV-1–infected individuals.

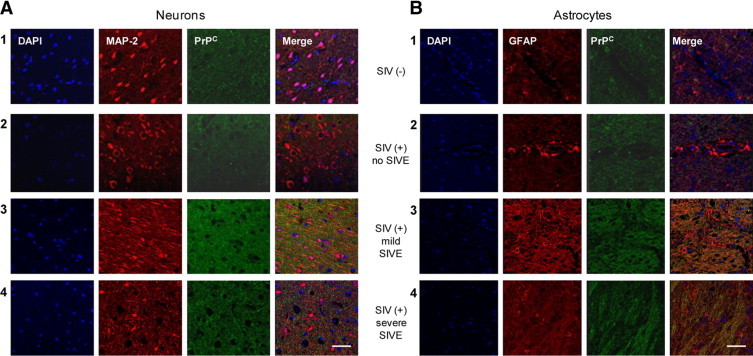

CNS PrPC Is Elevated in SIV-Infected Pigtail Macaques with Encephalitis

To examine alterations in PrPC throughout the course of infection and during progression of neurological disease, we used the pigtail macaque model of neuroAIDS. In this model, more than 90% of animals develop SIV encephalitis (SIVE) within 3 months of inoculation.43 We compared CNS PrPC of SIV-infected animals with mild SIVE, with severe SIVE, and without encephalitis to uninfected animals using immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy (Figure 3). MAP2 (Cy3-red) was used as a neuronal marker, and GFAP (Cy3-red) was used to detect astrocyte PrPC (FITC-green). We found neuronal (Figure 3A) and astrocytic (Figure 3B) PrPC to be elevated in both mildly (Figure 3, A and B, panel 3) and severely (Figure 3, A and B, panel 4) encephalitic animals as compared to uninfected animals (Figure 3, A and B, panel 1), and infected animals without encephalitis (Figure 3, A and B, panel 2). PrPC expression did not differ between animals with mild and severe SIVE. In these animals, increased CSF viral titers and CCL2 correspond only with severity of SIVE.32,44 Therefore, CNS PrPC elevation in the tissue sections is associated with SIV-mediated brain pathology. Thus, CNS PrPC increase is likely a product of the complex pathological processes associated with HIV/SIV infection.

Figure 3.

CNS PrPC is increased in pigtail macaques with SIV encephalitis. Brain sections from two uninfected pigtail macaques, one SIV-infected macaque without encephalitis, and three SIV-infected macaques with mild and three with severe SIV encephalitis (SIVE) were evaluated by immunohistochemistry using confocal microscopy. A: Neuronal expression of PrPC (FITC-green) was evaluated using MAP2 (Cy3-red; neuronal marker). B: Astrocyte expression of PrPC was indicated by GFAP (Cy3-red; astrocytic marker) and PrPC (FITC-green) colocalization. PrPC expression was elevated in neurons and astrocytes in animals with encephalitis (panels 3 and 4) relative to uninfected animals (panel 1) and animals infected with SIV without encephalitis (panel 2). There was no detectable difference in PrPC expression between mildly and severely encephalitis animals. PrPC was consistently elevated in all encephalitis tissue examined.

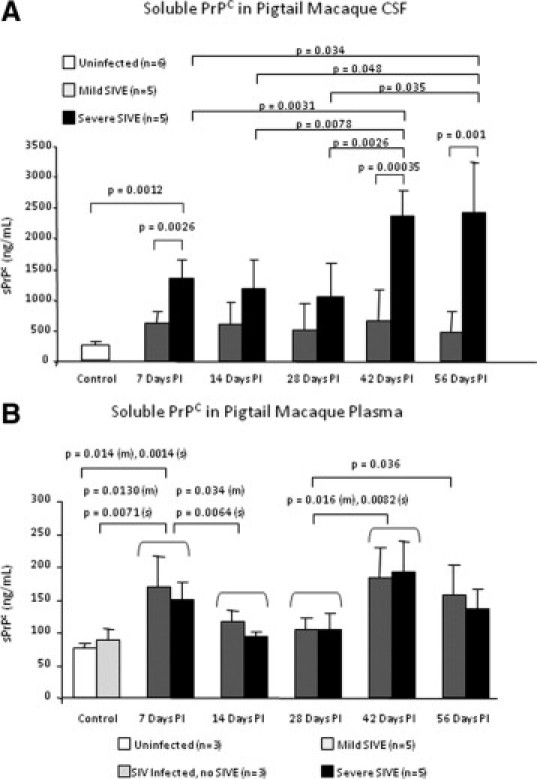

CSF Soluble PrPC Levels Correlate with Severity of Encephalitis in SIV-Infected Macaques

CSF levels of sPrPC were found to correlate positively with HAND. Thus, we examined the CSF and plasma of SIV-infected pigtail macaques to characterize PrPC release during the course of neuroAIDS. The pigtail macaque model provides the opportunity to evaluate tissues from SIV-infected animals at acute, asymptomatic, and late stages of an accelerated disease process. This enables examination of sequential time points during infection and disease development that cannot be evaluated in humans. These animals demonstrate a characteristic pattern of disease in which there is early CNS viral entry, followed by extensive CNS viral replication and associated neuroinflammation between 4–7 days postinoculation (PI). Between days 14 and 21 PI, CNS viral load drops, as do markers of CNS inflammation, particularly CCL2. In those animals that develop substantial encephalitis, a recrudescence of viral activity and neuroinflammation is evident at approximately day 28 PI and continues through 56 days PI. During this time, CSF viral load and CCL2 levels are predictive of severity of pathology.32,44

CSF and plasma sPrPC were evaluated during different stages of SIV infection using ELISA. Similar to findings in the human, macaque CSF sPrPC levels were five- to 10-fold higher than plasma levels (Figure 4). Animals that develop severe encephalitis have elevated CSF sPrPC levels at early (7 days PI) and late (42–56 days PI) stages of infection as compared to uninfected animals and animals with mild SIVE (Figure 4A). Furthermore, severely encephalitic animals have significantly higher CSF sPrPC levels at 42 to 56 days PI than at earlier stages in the disease process. This corresponds with high CNS viral titers and CCL2 levels. We did not observe increased sPrPC in mild SIVE. However, this is a characterized by low CCL2 and low viral replication, two factors that we propose participates in PrPC shedding/release. We also do not have behavioral studies of these animals and therefore cannot assess whether high sPrPC CSF is a biomarker of cognitive status in this animal model. There was no significant difference in plasma sPrPC between animals that develop severe and mild SIVE (Figure 4B). However, plasma sPrPC of encephalitic animals is elevated early during CNS infection (7 days PI) and late in the disease process (42–56 day PI) relative to uninfected animals and infected animals without SIVE. Early increases in plasma sPrPC may reflect release from leukocytes during seroconversion, while late increases may be related to sPrPC leakage through a dysfunctional BBB in response to high viral activity and neuroinflammation.45 These findings indicate that CSF but not plasma sPrPC correlates with severity of pathology in SIV-infected macaques and support CSF sPrPC as a biomarker of HIV/SIV-mediated CNS dysfunction.

Figure 4.

CSF soluble PrPC levels correlate with severity of encephalitis in the pigtail macaque model of neuroAIDS. CSF and plasma was obtained once per week after infection with SIV until the time of sacrifice at 56 days postinoculation (PI). Soluble PrPC was evaluated by ELISA. A: The CSF from animals that developed severe SIVE contained higher levels of sPrPC than the CSF of those developing mild SIVE with a pronounced difference seen in late stages of disease. The increased levels of CSF sPrPC in severely encephalitic animals at days 42 and 56 PI correlated with increased CSF viral RNA and CCL2 levels. B: The plasma from SIV-infected encephalitic pigtail macaques (m = mild, s = severe) contained higher levels of sPrPC than the plasma from uninfected and infected animals without encephalitis at time points associated with high CNS viral load and inflammation. There was no difference in plasma sPrPC levels in animals that developed mild and severe encephalitis. Increased sPrPC at 7 days PI corresponded with high CNS viral activity and CSF CCL2 levels, followed by an antiviral and immunosuppressive response between 14–28 days PI and a concomitant drop in sPrPC levels. At 42 days PI, concordant with recrudescence of neuroinflammation and rebound of CNS viral load, CSF and plasma levels of sPrPC rose. CSF but not plasma sPrPC predicts severity of encephalitis in SIV-infected pigtail macaques.

CCL2 and HIV-1 Infection Increase PrPC Release from Cells Involved in CNS Pathology

In humans, elevated CSF CCL2 levels correlate with both CNS pathology and neurocognitive impairment,27,28 while in pigtail macaques, increasing CSF CCL2 levels and viral load are predictive of severity of encephalitis.32,44 We found CSF sPrPC to correlate with CSF CCL2 levels in HIV-infected individuals. We also found CSF sPrPC to be elevated selectively in animals with severe SIVE, particularly at stages in the disease process associated with high CSF CCL2 levels and viral rebound. We therefore hypothesized that CCL2 and/or HIV-1 infection affect PrPC release. ELISA was performed on media collected from cultures of cells known to participate in HIV-associated CNS pathology. Primary human neurons, astrocytes, HBMVECs, macrophages, monocytes, and PBMCs were all found to release PrPC at baseline levels in vitro (Table 3).

Table 3.

CCL2 Increases Release of PrPC from Human Cells Important to HIV-Mediated CNS Pathology in Vitro

| Neurons | Astrocytes | Neuron Astrocyte cocultures | Astrocyte media transfer to neurons | BMVECs | Macrophages | Monocytes | PBMCs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline PrPC release | 38.78 ng/ml/105 cells after 24 hours | 128.85 ng/ml/105 cells after 24 hours | 62.80 ng/ml/105 cells after 24 hours | 38.26 ng/ml/105 cells after 24 hours | 12.94 ng/ml/105 cells after 24 hours | 41.33 ng/ml/105 cells after 24 hours | 12.17 ng/ml/105 cells after 24 hours | 172.43 ng/ml/105 cells after 24 hours |

| Effect of CCL2 on PrPC release | 2.2-fold increase (30 m) P = 0.019 | No change (30 m to 6 hours) | 1.6-fold increase (30 m) P = 0.042 | No change (30 m to 2 hours) | No change (30 m to 2 hours) | No change (1 to 5 days) | ND | No change (1 to 5 days) |

| 2.1-fold increase (2 hours) P = 0.026 | 1.6-fold increase (2 hours) P = 0.0013 | |||||||

| 1.9-fold increase (6 hours) P = 0.014 | 3.3-fold increase (6 hours) P = 0.0065 | 3.4-fold increase (6 hours) P = 0.00092 | 2.1-fold increase (6 hours) P = 0.028 | |||||

| 1.3-fold increase (24 hours) P = 0.010 | 2.5-fold increase (24 hours) P = 0.0017 | 4.0-fold increase (24 hours) P = 0.0029 | 5.1-fold increase (24 hours) P = 0.043 | 2.9-fold increase (24 hours) P = 0.034 | ||||

| Effect of HIV-1ADA on PrPC shedding | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | No change (1 to 5 days PI) | 1.7-fold increase (1 day PI) P = 0.036 | 1.5-fold increase (1 day PI) P = 0.024 |

| 1.6-fold increase (3 days PI) P = 0.036 | 2.0-fold increase (3 days PI) P = 0.028 | |||||||

| 0.76-fold decrease (4 days PI) P = 0.035 | 0.59-fold decrease (5 days PI) P = 0.0034 | |||||||

| 0.58-fold decrease (7 days PI) P = 0.020 |

All fold changes were evaluated relative to control cells at same time point.

We selectively examined the effect of CCL2 on neuron, astrocyte, and HBMVEC PrPC release, as these cells are not productively infected with HIV or support only low level, restricted infection in vitro.46,47 CCL2 increases PrPC release from neurons between 30 minutes and 24 hours, while release from astrocytes is increased only after 24 hours of CCL2 exposure (Table 3). Interestingly, higher levels of PrPC are released from co-cultures of neurons and astrocytes after 6 and 24 hours of CCL2 treatment than are obtained from either cell type cultured alone (Table 3). This suggests communication between astrocytes and neurons in response to CCL2 that facilitates PrPC release. We therefore treated astrocytes with CCL2 for 6 hours, a time point not associated with increased astrocyte PrPC release, and transferred the media to neuron cultures. Neurons were incubated with this media for 30 minutes to 24 hours, followed by measurement of sPrPC levels. After subtracting the contribution of sPrPC from the astrocytes and neurons before media transfer, neurons were found to increase their release of PrPC after 6–24 hours (Table 3). This suggests that astrocytes produce a soluble mediator in response to CCL2 that interacts with neurons and induces PrPC release. HBMVECs also release PrPC after 6–24 hours of CCL2 treatment. The similar kinetics of CCL2-induced PrPC release from neuron/astrocyte co-cultures, neurons cultured with media from CCL2-treated astrocytes, and from HBMVECs may be indicative of a common release mechanism.

The effects of CCL2 and HIV-1 infection on macrophages, monocytes, and PBMCs were also examined. Macrophages were treated with CCL2, infected with HIV-1ADA, or concomitantly infected and treated with CCL2. Soluble PrPC was measured from culture media and compared to vehicle-treated cells. Neither CCL2 nor HIV-1 alters PrPC release from macrophages (Table 3). CCL2 also does not alter the release of PrPC from human PBMCs (Table 3). However, HIV-1 infection is associated with an early increase in PrPC release from both monocytes and PBMCs between 1–3 days postinfection (Table 3). This is followed by a precipitous and sustained decline in PrPC release that is not attributed to cell death. Concomitant CCL2 treatment of PBMCs during HIV-1 infection does not further alter PrPC release (data not shown). These findings suggest that neurons, astrocytes, and HBMVECs may be the predominant source of sPrPC in the CSF of individuals infected with HIV-1 and that CCL2 plays a prominent role in CNS PrPC release. Leukocytes may also be an important source of CNS sPrPC when they become infected after entering the CNS.

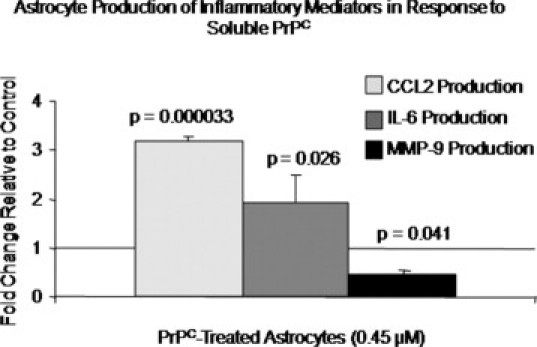

Soluble PrPC Mediates the Production of Inflammatory Factors by Astrocytes

Astrocytes are an abundant cell type in the CNS,48 play a prominent role in HIV-associated neuroinflammation,47 and release PrPC at high baseline levels in vitro (Figure 5). Therefore, to examine a functional consequence of sPrPC in the CNS, we treated primary human astrocytes with full-length recombinant human PrPC (recPrPC) in vitro. Astrocytes were treated with 0.45 μmol/L recPrPC for 6 hours, a time frame compatible with de novo synthesis of protein, followed by assay of media for soluble inflammatory factors by ELISA. This concentration of recPrPC was found to promote maximal axonal growth, neuritogenesis, and synaptic maturity in embryonic rat neurons.49 We examined release of IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, and MMP-9, factors elevated in the CSF of HIV-1–infected individuals with neurocognitive impairment,28,50–53 in recPrPC-treated astrocytes relative to vehicle-treated cultures. In response to recPrPC, astrocytes release IL-6 and CCL2, while decreasing their baseline secretion of MMP-9 (Figure 5). TNF-α production was below the limit of detection of the assay in both treated and untreated cultures. This demonstrates a specific astrocyte response to sPrPC and not simply generalized activation. Thus, sPrPC alters astrocyte function. By modulating the production of inflammatory factors, sPrPC plays an important role in HIV-1–mediated CNS pathology.

Figure 5.

Soluble PrPC alters the production of inflammatory mediators by astrocytes. Astrocytes were treated with 0.45 μmol/L recombinant human full-length PrPC (recPrPC) for 6 hours, followed by collection of media and evaluation by ELISA in three independent experiments. Astrocyte production of CCL2, IL-6, and MMP-9 in response to recPrPC was evaluated relative to vehicle-treated cells and is reported as fold change. Astrocytes secreted CCL2 and IL-6 in response to recPrPC, whereas their production of MMP-9 was reduced below baseline. These findings indicate that sPrPC modulates the inflammatory response of astrocytes and contributes to HIV-mediated neuroinflammation.

Discussion

This is the first study to demonstrate that sPrPC in the CSF is a biomarker of cognitive impairment in the HIV infected population. We find that PrPC is highly increased in the brain and released into the CSF of neurocognitively impaired HIV-1–infected individuals. We propose that this pattern of elevated brain expression and increased CSF sPrPC is specific to HIV-1–mediated neurocognitive impairment and is not a generalized phenomenon of neuronal injury or neuroinflammation. This is supported by several findings. First, CNS PrPC is regionally increased in individuals with Alzheimer disease54,55 but not Lewy body dementia,54 suggesting that PrPC elevation is not a general finding in dementias with prominent neuronal pathologies. Second, brain PrPC is increased after acute stroke, but not after prolonged ischemia,56 indicating a lack of direct correlation with inflammation. Furthermore, CSF sPrPC is decreased in Alzheimer disease, Lewy body dementia, and Parkinson disease but does not significantly differ from normal controls in multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, cerebral ischemia, or infectious encephalitis and meningitis.40 This indicates that CSF sPrPC levels do not independently correlate with brain PrPC expression, neuronal injury, or neuroinflammation. Rather, these collective findings suggest that elevated brain PrPC and CSF sPrPC are a specific biomarker of HAND.

We show that HIV-1 infection and the chemokine CCL2 increase PrPC release from cells involved in CNS pathology. Furthermore, soluble PrPC is an important mediator of the astrocyte inflammatory response by increasing CCL2 and IL-6 production. PrPC dysregulation during HIV-1 infection may be simultaneously cytoprotective and pathological. Both membrane-bound and soluble PrPC are neurotrophic and neuroprotective.15,18–20,26,49 However, PrPC is associated with microglial24 and leukocyte activation21 and cellular taxis,57 processes that contribute to CNS dysfunction during HIV-1 infection.58 It is possible that the increase we see in PrPC staining of CNS tissue from HIV-infected unimpaired individuals as compared with normal brains is an early protective response. PrPC is not shed into the CSF under these early conditions. We suggest that only once the events that lead to cognitive impairment have occurred within the CNS that result in even higher CNS PrPC expression, will shedding/release of significant amounts of sPrPC into the CSF occur.

The CCL2 and IL-6 produced by astrocytes in response to sPrPC may also have opposing effects, as both CCL2 and IL-6 are associated with early neuroprotection,37,59–61 followed by chronic inflammatory damage.62,63 Similarly, decreased MMP-9 expression may be part of the initial neuroprotective role of PrPC. Thus, PrPC dysregulation during HIV-1 infection may be an initial compensatory response, with pathological consequences during chronic disease.

In the pigtail macaque model of neuroAIDS, CSF sPrPC correlates with severe encephalitis. However, we do not have behavioral studies of these animals and therefore cannot assess the predictive value of this finding. Importantly, our findings in humans indicate that CSF sPrPC may be predictive of neurocognitive impairment and CNS pathology in HIV-1–infected individuals. This could be a significant advancement in medical diagnosis, monitoring, and management of individuals infected with HIV-1. No biomarkers have been identified that are specific to HAND. The need for such biomarkers and their medical utility has been clearly defined by the HIV biomedical research community.64 Our data indicate that CSF sPrPC is a potential prognostic indicator of CNS dysfunction and neurocognitive impairment in HIV-1–infected individuals.

We provide the first evidence of PrPC dysregulation in HIV-1–infected individuals and that it is shed into the CSF of HIV-infected people with cognitive impairment. We also demonstrate a role for sPrPC in HIV-1–mediated CNS pathology. Our data indicate that CSF sPrPC may be the first biomarker identified that can predict neurocognitive impairment in HIV-1–infected individuals. These data further characterize the neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 CNS disease and identify a novel target for monitoring CNS disease progression in infected individuals.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Brad Poulos and the Human Fetal Tissue Repository, the Analytical Imaging Facility, and the Center for AIDS Research Immunology/Pathology Core (Albert Einstein College of Medicine). We thank Dr. Clarisa M. Buckner, Dr. Peter J. Gaskill, and Lillie Lopez who prepared some of the cultures used in these studies. We thank the patients and staff of the Manhattan HIV Brain Bank.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01MH075679 (J.W.B.), MH52974 and MH070297 (E.A.E. and J.W.B.), MH076679 (E.A.E.), R24MH59724 and U01MH083501 (S.M.), R01NS055648 and P01MH070306 (J.E.C.), R01MH069116 and R01NS44815 (M.C.Z.); by grant AI-051519 from the NIH Centers for AIDS Research (T.K.R., E.A.E., and J.W.B.); by grant M01-RR-00071 from the Clinical Research Center of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine (S.M.); and by AI071326pre-doctoral fellowship (T.K.R).

A guest editor acted as editor-in-chief for this manuscript. No person at Thomas Jefferson University or Albert Einstein College of Medicine was involved in the peer review process or final disposition for this article.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . Report on the global AIDS epidemic 2008. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Lorenzini P, Bellagamba R, Galgani S, Corpolongo A, Vlassi C, Larussa D, Zaccarelli M, Noto P, Visco-Comandini U, Giulianelli M, Ippolito G, Antinori A, Narciso P. Prevalence and risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive impairment, 1996 to 2002: results from an urban observational cohort. J Neurovirol. 2005;11:265–273. doi: 10.1080/13550280590952790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Gorp WG, Baerwald JP, Ferrando SJ, McElhiney MC, Rabkin JG. The relationship between employment and neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5:534–539. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799566071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, Sadek J, Moore DJ, Bentley H, McCutchan JA, Reicks C, Grant I. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:317–331. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacktor N, Lyles RH, Skolasky R, Kleeberger C, Selnes OA, Miller EN, Becker JT, Cohen B, McArthur JC. HIV-associated neurologic disease incidence changes: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, 1990–1998. Neurology. 2001;56:257–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dore GJ, Correll PK, Li Y, Kaldor JM, Cooper DA, Brew BJ. Changes to AIDS dementia complex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:1249–1253. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907090-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esiri MM, Carter J, Ironside JW. Prion protein immunoreactivity in brain samples from an unselected autopsy population: findings in 200 consecutive cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2000;26:273–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2000.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLennan NF, Rennison KA, Bell JE, Ironside JW. In situ hybridization analysis of PrP mRNA in human CNS tissues. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2001;27:373–383. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deli MA, Sakaguchi S, Nakaoke R, Abraham CS, Takahata H, Kopacek J, Shigematsu K, Katamine S, Niwa M. PrP fragment 106–126 is toxic to cerebral endothelial cells expressing PrP(C) Neuroreport. 2000;11:3931–3936. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011270-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitsios N, Saka M, Krupinski J, Pennucci R, Sanfeliu C, Miguel Turu M, Gaffney J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Sullivan M, Slevin M. Cellular prion protein is increased in the plasma and peri-infarcted brain tissue after acute stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:602–611. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durig J, Giese A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Rosenthal C, Schmucker U, Bieschke J, Duhrsen U, Kretzschmar HA. Differential constitutive and activation-dependent expression of prion protein in human peripheral blood leucocytes. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:488–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stahl N, Borchelt DR, Hsiao K, Prusiner SB. Scrapie prion protein contains a phosphatidylinositol glycolipid. Cell. 1987;51:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitt-Ulms G, Legname G, Baldwin MA, Ball HL, Bradon N, Bosque PJ, Crossin KL, Edelman GM, DeArmond SJ, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Binding of neural cell adhesion molecules (N-CAMs) to the cellular prion protein. J Mol Biol. 2001;314:1209–1225. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.5183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graner E, Mercadante AF, Zanata SM, Forlenza OV, Cabral AL, Veiga SS, Juliano MA, Roesler R, Walz R, Minetti A, Izquierdo I, Martins VR, Brentani RR. Cellular prion protein binds laminin and mediates neuritogenesis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;76:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viegas P, Chaverot N, Enslen H, Perriere N, Couraud PO, Cazaubon S. Junctional expression of the prion protein PrPC by brain endothelial cells: a role in trans-endothelial migration of human monocytes. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4634–4643. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coitinho AS, Freitas AR, Lopes MH, Hajj GN, Roesler R, Walz R, Rossato JI, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Martins VR, Brentani RR. The interaction between prion protein and laminin modulates memory consolidation. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:3255–3264. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajj GN, Lopes MH, Mercadante AF, Veiga SS, da Silveira RB, Santos TG, Ribeiro KC, Juliano MA, Jacchieri SG, Zanata SM, Martins VR. Cellular prion protein interaction with vitronectin supports axonal growth and is compensated by integrins. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1915–1926. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiarini LB, Freitas AR, Zanata SM, Brentani RR, Martins VR, Linden R. Cellular prion protein transduces neuroprotective signals. EMBO J. 2002;21:3317–3326. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopes MH, Hajj GN, Muras AG, Mancini GL, Castro RM, Ribeiro KC, Brentani RR, Linden R, Martins VR. Interaction of cellular prion and stress-inducible protein 1 promotes neuritogenesis and neuroprotection by distinct signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11330–11339. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2313-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattei V, Garofalo T, Misasi R, Circella A, Manganelli V, Lucania G, Pavan A, Sorice M. Prion protein is a component of the multimolecular signaling complex involved in T cell activation. FEBS Lett. 2004;560:14–18. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Almeida CJ, Chiarini LB, da Silva JP, PM ES, Martins MA, Linden R. The cellular prion protein modulates phagocytosis and inflammatory response. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:238–246. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bainbridge J, Walker KB. The normal cellular form of prion protein modulates T cell responses. Immunol Lett. 2005;96:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown DR, Besinger A, Herms JW, Kretzschmar HA. Microglial expression of the prion protein. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1425–1429. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199805110-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown DR, Mohn CM. Astrocytic glutamate uptake and prion protein expression. Glia. 1999;25:282–292. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(19990201)25:3<282::aid-glia8>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khosravani H, Zhang Y, Tsutsui S, Hameed S, Altier C, Hamid J, Chen L, Villemaire M, Ali Z, Jirik FR, Zamponi GW. Prion protein attenuates excitotoxicity by inhibiting NMDA receptors. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:551–565. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cinque P, Vago L, Mengozzi M, Torri V, Ceresa D, Vicenzi E, Transidico P, Vagani A, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Lazzarin A, Poli G. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 correlate with HIV-1 encephalitis and local viral replication. AIDS. 1998;12:1327–1332. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199811000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conant K, Garzino-Demo A, Nath A, McArthur JC, Halliday W, Power C, Gallo RC, Major EO. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in HIV-1 Tat-stimulated astrocytes and elevation in AIDS dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3117–3121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan EL, Morgello S, Isaacs K, Naseer M, Gerits P. Neuropsychiatric impact of hepatitis C on advanced HIV. Neurology. 2004;62:957–962. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115177.74976.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clinical confirmation of the American Academy of Neurology algorithm for HIV-1-associated cognitive/motor disorder. The Dana Consortium on Therapy for HIV Dementia and Related Cognitive Disorders. Neurology. 1996;47:1247–1253. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zink MC, Amedee AM, Mankowski JL, Craig L, Didier P, Carter DL, Munoz A, Murphey-Corb M, Clements JE. Pathogenesis of SIV encephalitis: selection and replication of neurovirulent SIV. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:793–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zink MC, Suryanarayana K, Mankowski JL, Shen A, Piatak M, Jr, Spelman JP, Carter DL, Adams RJ, Lifson JD, Clements JE. High viral load in the cerebrospinal fluid and brain correlates with severity of simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Virol. 1999;73:10480–10488. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10480-10488.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mankowski JL, Queen SE, Clements JE, Zink MC. Cerebrospinal fluid markers that predict SIV CNS disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witwer KW, Gama L, Li M, Bartizal CM, Queen SE, Varrone JJ, Brice AK, Graham DR, Tarwater PM, Mankowski JL, Zink MC, Clements JE. Coordinated regulation of SIV replication and immune responses in the CNS. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zink MC, Clements JE. A novel simian immunodeficiency virus model that provides insight into mechanisms of human immunodeficiency virus central nervous system disease. J Neurovirol. 2002;8(suppl 2):42–48. doi: 10.1080/13550280290101076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eugenin EA, Berman JW. Chemokine-dependent mechanisms of leukocyte trafficking across a model of the blood-brain barrier. Methods. 2003;29:351–361. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eugenin EA, King JE, Nath A, Calderon TM, Zukin RS, Bennett MV, Berman JW. HIV-tat induces formation of an LRP-PSD-95- NMDAR-nNOS complex that promotes apoptosis in neurons and astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3438–3443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Everall I, Vaida F, Khanlou N, Lazzaretto D, Achim C, Letendre S, Moore D, Ellis R, Cherne M, Gelman B, Morgello S, Singer E, Grant I, Masliah E. Cliniconeuropathologic correlates of human immunodeficiency virus in the era of antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:360–370. doi: 10.3109/13550280903131915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volkel D, Zimmermann K, Zerr I, Bodemer M, Lindner T, Turecek PL, Poser S, Schwarz HP. Immunochemical determination of cellular prion protein in plasma from healthy subjects and patients with sporadic CJD or other neurologic diseases. Transfusion. 2001;41:441–448. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41040441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyne F, Gloeckner SF, Ciesielczyk B, Heinemann U, Krasnianski A, Meissner B, Zerr I. Total prion protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are reduced in patients with various neurological disorders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:863–873. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berman JW, Guida MP, Warren J, Amat J, Brosnan CF. Localization of monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1 expression in the central nervous system in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and trauma in the rat. J Immunol. 1996;156:3017–3023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King JE, Eugenin EA, Hazleton JE, Morgello S, Berman JW. Mechanisms of HIV-tat-induced phosphorylation of N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit 2A in human primary neurons: implications for NeuroAIDS pathogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2819–2830. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clements JE, Mankowski JL, Gama L, Zink MC. The accelerated simian immunodeficiency virus macaque model of human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurological disease: from mechanism to treatment. J Neurovirol. 2008;14:309–317. doi: 10.1080/13550280802132832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zink MC, Coleman GD, Mankowski JL, Adams RJ, Tarwater PM, Fox K, Clements JE. Increased macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 in cerebrospinal fluid precedes and predicts simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1015–1021. doi: 10.1086/323478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mankowski JL, Queen SE, Kirstein LM, Spelman JP, Laterra J, Simpson IA, Adams RJ, Clements JE, Zink MC. Alterations in blood-brain barrier glucose transport in SIV-infected macaques. J Neurovirol. 1999;5:695–702. doi: 10.3109/13550289909021298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eugenin EA, Berman JW. Gap junctions mediate human immunodeficiency virus-bystander killing in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12844–12850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4154-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blumberg BM, Gelbard HA, Epstein LG. HIV-1 infection of the developing nervous system: central role of astrocytes in pathogenesis. Virus Res. 1994;32:253–267. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azevedo FA, Carvalho LR, Grinberg LT, Farfel JM, Ferretti RE, Leite RE, Jacob Filho W, Lent R, Herculano-Houzel S. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:532–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanaani J, Prusiner SB, Diacovo J, Baekkeskov S, Legname G. Recombinant prion protein induces rapid polarization and development of synapses in embryonic rat hippocampal neurons in vitro. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1373–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelder W, McArthur JC, Nance-Sproson T, McClernon D, Griffin DE. Beta-chemokines MCP-1 and RANTES are selectively increased in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:831–835. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Conant K, McArthur JC, Griffin DE, Sjulson L, Wahl LM, Irani DN. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of MMP-2, 7, and 9 are elevated in association with human immunodeficiency virus dementia. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:391–398. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<391::aid-ana15>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perrella O, Guerriero M, Izzo E, Soscia M, Carrieri PB. Interleukin-6 and granulocyte macrophage-CSF in the cerebrospinal fluid from HIV infected subjects with involvement of the central nervous system. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1992;50:180–182. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1992000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimaldi LM, Martino GV, Franciotta DM, Brustia R, Castagna A, Pristera R, Lazzarin A. Elevated alpha-tumor necrosis factor levels in spinal fluid from HIV-1-infected patients with central nervous system involvement. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:21–25. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rezaie P, Pontikis CC, Hudson L, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL. Expression of cellular prion protein in the frontal and occipital lobe in Alzheimer's disease, diffuse Lewy body disease, and in normal brain: an immunohistochemical study. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:929–940. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6551.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voigtlander T, Kloppel S, Birner P, Jarius C, Flicker H, Verghese-Nikolakaki S, Sklaviadis T, Guentchev M, Budka H. Marked increase of neuronal prion protein immunoreactivity in Alzheimer's disease and human prion diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101:417–423. doi: 10.1007/s004010100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weise J, Crome O, Sandau R, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Bahr M, Zerr I. Upregulation of cellular prion protein (PrPc) after focal cerebral ischemia and influence of lesion severity. Neurosci Lett. 2004;372:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schrock Y, Solis GP, Stuermer CA. Regulation of focal adhesion formation and filopodia extension by the cellular prion protein (PrPC) FEBS Lett. 2009;583:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.D'Aversa TG, Yu KO, Berman JW. Expression of chemokines by human fetal microglia after treatment with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protein Tat. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:86–97. doi: 10.1080/13550280490279807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Penkowa M, Giralt M, Lago N, Camats J, Carrasco J, Hernandez J, Molinero A, Campbell IL, Hidalgo J. Astrocyte-targeted expression of IL-6 protects the CNS against a focal brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2003;181:130–148. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(02)00051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yao H, Peng F, Dhillon N, Callen S, Bokhari S, Stehno-Bittel L, Ahmad SO, Wang JQ, Buch S. Involvement of TRPC channels in CCL2-mediated neuroprotection against tat toxicity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1657–1669. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2781-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eugenin EA, D'Aversa TG, Lopez L, Calderon TM, Berman JW. MCP-1 (CCL2) protects human neurons and astrocytes from NMDA or HIV-tat-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1299–1311. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ge S, Murugesan N, Pachter JS. Astrocyte- and endothelial-targeted CCL2 conditional knockout mice: critical tools for studying the pathogenesis of neuroinflammation. J Mol Neurosci. 2009;39:269–283. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brett FM, Mizisin AP, Powell HC, Campbell IL. Evolution of neuropathologic abnormalities associated with blood-brain barrier breakdown in transgenic mice expressing interleukin-6 in astrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:766–775. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brew BJ, Letendre SL. Biomarkers of HIV related central nervous system disease. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:73–88. doi: 10.1080/09540260701878082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]