Abstract

Adult subventricular zone (SVZ)-derived neural stem cells (NSCs) have therapeutic effects in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, an animal model of multiple sclerosis. However, SVZ precursor cells as a source of NSCs are not readily accessible for clinical application. In the present study, we demonstrate that NSCs derived from bone marrow (BM) cells exhibit comparable morphological properties as those derived from SVZ cells and possess a similar ability to differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes both in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, both types of NSCs suppressed chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis to a comparable extent on transplantation. Mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of NSCs include immunomodulation in the periphery and the central nervous system (CNS), neuron/oligodendrocyte repopulation by transplanted cells, and enhanced endogenous remyelination and axonal recovery. Furthermore, we provide evidence for the trans-differentiation of transplanted BM-NSCs into neural cells in the CNS, while no fusion of these cells with host neural cells was detected. This is the first study that directly compares SVZ- versus BM-NSCs with regard to in vivo neural differentiation and anti-inflammatory and therapeutic effects on CNS inflammatory demyelination. Their virtually identical therapeutic potential, greater accessibility, and autologous properties make BM-NSCs a novel and highly applicable substitute for SVZ-NSCs in cell-based multiple sclerosis therapies.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory demyelinating disease resulting from an autoimmune response against central nervous system (CNS) myelin. Inflammatory infiltration and demyelination of the CNS are hallmarks of MS and its animal model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).1–3 MS begins when peripherally activated myelin-reactive T cells infiltrate into the CNS, followed closely by other immune cells, including naïve myelin-reactive T cells, polyclonal T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, B cells, and neutrophils.1–4 Once in the CNS, myelin-reactive T cells are presented with myelin antigens, and become activated/reactivated, thereby triggering an immunological cascade that results in myelin damage. This process occurs in the initial phase of the disease and continues to some extent during the chronic and relapse phases.2,5 Despite extensive research aimed at developing pharmacotherapeutic agents to reduce myelin damage, only a few therapies are available (eg, interferon [IFN]-β, glatiramer acetate, and mitoxantrone), all with potential side effects and only modest to moderate efficacy.1,6

Recent studies have shown the therapeutic potential of neural stem cells (NSCs) in EAE.7–11 NSCs exhibit stem cell properties, including self-renewal, production of a large number of progeny and differentiation into the three primary CNS phenotypes: neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. Because NSCs have the ability to support neurogenesis throughout adulthood and exert immunomodulatory properties, they have been evaluated as a renewable source of neural precursors for regenerative transplantation in various CNS diseases, including degenerative disorders, injury, and cancers.12,13

Although NSCs can be isolated from the subventricular zone (SVZ) of adult mammalian CNS, this source of NSCs is hardly accessible for clinical application. This problem led us to search for alternative sources for SVZ-NSCs. Recently it has been shown that cells resembling NSCs can be generated from adult rodent bone marrow (BM). These BM-derived NSCs (BM-NSCs) have similar morphological properties and cellular markers as SVZ-NSCs,14,15 and are thus potentially a clinically feasible alternative to SVZ-NSCs for therapy of MS.

In the present study, we compared the biological and functional properties of NSCs from BM and SVZ in vitro and in vivo. Transplantation of BM-NSCs suppressed EAE to a similar extent as SVZ-NSCs and BM-NSCs had a similar capacity to differentiate into neural cells in vitro and in vivo. The availability of autologous BM-NSCs, ie, the patient him/herself being the donor, represents a great advantage of this approach over other alternatives, such as NSCs derived from cord blood. Equal therapeutic efficacy of BM-NSCs, together with easy accessibility of BM cells and absence of ethical issues, provide a rationale for considering BM-NSCs advantageous to SVZ-NSCs in MS therapy.

Materials and Methods

Generation and Differentiation of BM- and SVZ-NSCs

To generate BM-NSCs, whole BM was harvested from the femurs of adult female green fluroescent protein (GFP) transgenic mice that constitutively express GFP (C57BL/6-Tg [ACTB-EGFP] 1Osb, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) at 8 to 12 weeks of age. After lysis of red blood cells, lineage+ cells were depleted by using Microbeads (Lineage Cell Depletion Kit; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) for the depletion of mature hematopoietic cells. The lineage− cells (CD5−, CD45−, CD11b−, Gr-1−, TER119−, and 7/4−) were left untouched, thus allowing further separation of Sca-1+ cells using anti-Sca-1 Microbead Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). The phenotype of these lineage−/Sca-1+ cells was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis as CD73+, CD9+, Sca-1+, CD45−, and CD11b−.3,16–18 The SVZ region of brain from the same adult mice was harvested to generate SVZ-NSCs following previously described protocols.9,14,15 Cells from both BM and SVZ at 5th to 10th passages were used for further in vitro and in vivo experiments. The self-renewal capacity of BM- and SVZ-NSCs was determined by developing a growth curve. Nestin expression was determined by immunocytochemistry.3,14,15,19

To induce NSC differentiation, dissociated single cells or small neurospheres were plated on poly-L-lysine–coated plates, incubated in stem cell differentiation medium for 10 to 14 days, and processed for immunocytochemistry staining.

EAE Induction and NSC Treatment

Female C57BL/6 mice at 8 to 12 weeks of age were injected subcutaneously with 200 μg MOG35-55 in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) containing 5 mg/ml Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco, Detroit, MI) over two sites on the back. All mice received 200 ng pertussis toxin (Campbell, CA) i.p. on days 0 and 2 postimmunization (p.i.). Clinical score was checked daily by two researchers blindly according to the 0 to 5 scale as follows20: 1, limp tail or waddling gait with tail tonicity; 2, waddling gait with limp tail (ataxia); 2.5, ataxia with partial limb paralysis; 3, full paralysis of one limb; 3.5, full paralysis of one limb with partial paralysis of second limb; 4, full paralysis of two limbs; 4.5, moribund; and 5, death. All work was performed in accordance with the guidelines for animal use and care at Thomas Jefferson University.

BM- and SVZ-NSC treatment was applied by i.v. injection of single dissociated NSCs (1.5 × 106 cells in 200 ml PBS/each mouse) via the tail vein at the peak of disease (day 22 p.i.). Sham-treated age-, sex-, and strain-matched mice injected i.v. with PBS were used as controls. All groups of animals were sacrificed 100 days p.i. Brain, spinal cord, and spleen were harvested for pathological and immunological assessments. As infiltration and demyelination lesions were consistently observed in the corpus callosum and in ventral areas of the lumbar spinal cord, all pathological/immunohistochemical studies were focused within standard 500 μm2 fields at specific sites within the ventral column of the lumbar spinal cord (at L3) and corpus callosum as shown previously.21–24

Histopathology

At the end of the experiment (day 100 p.i.), mice treated with NSCs were sacrificed and extensively perfused, and spinal cords were harvested. Seven-micrometer sections were stained with H&E for inflammation and Luxol fast blue (LFB) for demyelination, respectively. Slides were assessed in a blinded fashion for inflammation and demyelination as follows.25 For inflammation: 0, none; 1, a few inflammatory cells; 2, organization of perivascular infiltrates; and 3, increasing severity of perivascular cuffing with extension into the adjacent tissue. For demyelination: 0, none; 1, rare foci; 2, a few areas of demyelination; and 3, large (confluent) areas of demyelination. Quantification of CNS damage was performed on six sections per mouse, and five mice per group were analyzed.

Electron Microscopy

Lumbar spinal cords were fixed in fixative containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1% tannic acid, and 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer for 5 minutes × three times and stored at 5°C. Tissues were mounted in plastic blocks, processed through 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer supplied with 2% Os04 (Osmium), uranyl acetate, then dehydrated in acetone for 1.5 hours. After being embedded in Spurrs media, blocks were sectioned and stained. Sections were visualized by electron microscopy. Representative electron micrographs of each group were taken (kindly performed by Timothy Schneider, Department of Pathology, Thomas Jefferson University).

Quantification of Remyelination

Demyelination lesions were defined on the basis of myelin basic protein (MBP) expression in the corpus callosum. To quantify the amount of MBP expression, pixel intensity of MBP immunofluorescence was measured according to previous reports.26,27 MBP pixel intensity was measured at random areas of disease lesions at low power in the same image size by using ImageJ software (NIH ImageJ; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Total axon numbers did not differ significantly among measured areas. The mean pixel intensity was calculated from at least 25 images per mouse; four mice per group were evaluated. Remyelinated axons were defined by g ratio, a fraction of axon diameter divided by the entire fiber diameter of axon plus myelin sheath (measured by ImageJ software). Identification of abnormally thin myelin sheaths (greater than normal g ratio) remains the most reliable means of identifying remyelination.28,29 At least 50 myelinated axons on the electron micrographs were measured for each mouse; five mice per group were evaluated.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Seven-micrometer cryosections from NSC-treated mouse brain or NSCs maintained in growth medium or differentiation medium were fixed with 4% paraformaldyhyde plus 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 15 minutes, then washed twice with PBS. Sections were incubated with 10% goat serum in PBS for 30 to 60 minutes, after which primary antibodies were added and incubated at 4°C overnight. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-nestin (1:150; BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), rabbit anti-GFAP (1:100; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), rabbit anti-NG2 (1 μg/ml; Cell Signaling Solutions, Temecula, CA), mouse anti-GalC (1 μg/ml; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), mouse anti-NeuN (1:200; Chemicon), rabbit anti-Neurofilament NF-M, rabbit anti-Neurofilament H (NF-H; 1:100; StemCell Technologies), rabbit anti-Laminin (1:25; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), rat anti-CD45 (1:100; AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC), goat anti-CD4, mouse anti-CD8, goat-anti-CD68, and mouse anti-MBP (1:100), all from Santa Cruz Biotectechnology, Santa Cruz, CA. Primary antibodies were washed out with PBS three times after overnight incubation. Sections were then incubated with Cy5- or Cy3-conjugated species-specific secondary antibodies (all from Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab, West Grove, PA at 1:200 dilution) for 60 minutes at room temperature, followed by washing with PBS three times. Immunofluorescence controls were routinely performed with incubations in which primary antibodies were not included. Slides were covered with mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells expressing GFP (green), neural specific markers (red), and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) were identified as transplanted NSCs; other cells were double-labeled with DAPI and neural specific markers, whereas GFP− were identified as endogenous cells in the CNS. Cell counter of ImageJ software (NIH ImageJ) was used to count cells, and mean numbers were used for analysis. Results were visualized by fluorescent microscopy (Nikon Eclipse E600; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) or confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Cytokine Production by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Splenocytes of NSC-treated or untreated EAE mice were prepared at day 7 post-transplantation (p.t.) by pushing spleen tissue through a sterile 70-μm nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon 352350, Lincoln Park, NJ) to generate a single-cell suspension. Splenocytes, 1.5 × 106/ml, in duplicates were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum in 12-well plates and stimulated with 10 μg/ml MOG35-55 for 3 days. For co-culture studies, splenocytes of naïve MOG-transgenic mice were co-cultured with single NSCs at a ratio of 10:1 (splenocytes : NSCs). Cell-free supernatants were collected and analyzed for the production of interleukin (IL)-10, IL-17, and IFN-γ by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (BD Bioscience).

Apoptosis Assay by Flow Cytometry

To determine the potential influence of BM- and SVZ-NSCs on apoptosis of MOG-reactive T cells in vitro, Annexin-V-PE Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Bioscience) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Apoptosis was examined by the translocation of phosphatidylserine as determined by Annexin-V-PE staining. Splenocytes were isolated from naïve mice transgenic for T cell receptor (TCR) specific for MOG35-55 purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, and incubated at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum with purified anti-FasL antibody 250 ng/ml (no azide/low endotoxin; BD Pharmingen, Thornwood, NY) for 4 days to block FasL on T cells30,31 in the presence of MOG35-55 (10 μg/ml), then co-cultured with single NSCs at a ratio of 10:1 (splenocytes : NSCs) in the same medium. Splenocytes maintained in culture medium alone stimulated with MOG35-55 served as a control. After 24 hours' co-culture, cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD4, Annexin-V, and DAPI, then analyzed by flow cytometry. CD4+ cells were gated and their labeling with Annexin-V and DAPI was determined. Apoptotic cells were defined as CD4+, Annexin-V+, and DAPI−. Percentages of Annexin-V+ DAPI− cells among CD4+ T cells were calculated, and mean percentage was determined from five independent experiments.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical scores were analyzed by calculating the area under the curve for each mouse over the clinical period of the experiment. Differences between multiple groups were evaluated by the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. Experiments with two groups were tested for statistical significance by using unpaired, two-tailed, Student's t-tests. Differences were considered significant at a value of P < 0.05.

Results

Generation and Characterization of BM- and SVZ-NSCs in Vitro

SVZ cells and lineage−/Sca-1+ BM cells of adult GFP-transgenic mice were cultured as described in Materials and Methods. After 5 to 16 days in culture, individual cells proliferated to form distinct neurospheres as shown in Figure 1A. BM- and SVZ–NSCs exhibited similar morphological properties, such as neurosphere formation and similar cell shapes. As the spheres expanded, they detached from the plate and persisted as free-floating spheres of variable size. They were collected, dissociated to single cells, and reseeded at 1.0 × 105 cells/ml for a second round of or expansion. All of the BM- and SVZ-neurospheres tested were capable of secondary proliferation.

Figure 1.

Generation and characterization of BM- and SVZ-NSCs in vitro. SVZ cells and lineage−/Sca-1+ BM cells of adult GFP-transgenic mice were expanded in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 plus 20 ng/ml EGF, 20 ng/ml b-FGF, and 2% B27 supplements on poly-L-lysine-coated plates at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/ml. A: Phase-contrast images of typical primary neurospheres derived from BM and SVZ. After five to seven days in culture, a number of individual BM- and SVZ–NSCs increased and formed distinct neurospheres, which expanded in the subsequent cultures. All BM- and SVZ-neurospheres tested were capable of secondary expansion. Scale bar = 50 μm. B: Growth curves of BM- and SVZ–NSCs. Single BM- and SVZ–NSCs at the second and fifth passages were plated at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/ml and cultured in proliferation medium. At days 5, 9, 13, and 16, neurospheres in each well were dissociated into single cells; cell numbers per well were counted by hemocytometer. At least seven wells were assessed at each time point. The asterisk refers to the comparison between BM- and SVZ–NSCs at the second passage, *P < 0.05. One of three representative experiments is shown. C: Immunocytochemistry staining shows that both GFP+ BM and SVZ neurospheres (upper) or single NSCs (lower) are positive for nestin (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 250 μm in upper, 15 μm in lower. D: Differentiation of BM- and SVZ-NSCs in vitro. Dissociated single NSCs were cultured in differentiation medium for 14 days. Staining of neural specific markers (red) indicated that both BM- and SVZ-NSCs have differentiated into NF-M+ neurons, MBP+ mature oligodendrocytes, and GFAP+ astrocytes or remained undifferentiated (nestin+) as verified by immunostaining. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm. One of five representative experiments for A–D is shown.

We next compared the proliferation capacity of BM- and SVZ-NSCs. Single BM- and SVZ–NSCs at passages 2 and 5 were plated and cultured in proliferation medium. At days 5, 9, 13, and 16, neurospheres in each well were dissociated to single cells, and numbers of the cells per well were counted by hemocytometer. As shown in Figure 1B, SVZ-NSCs obtained at the second passage proliferated more than BM-NSCs, whereas there was no significant difference in proliferation at passage 5. We have observed that BM- and SVZ-NSCs proliferated in vitro for up to 15 weeks without changing morphology or phenotype (data not shown), consistent with previous observations.3,19 The expression of nestin was determined by immunocytochemistry at passage 5. Both GFP+ BM- and SVZ-neurospheres and single NSCs expressed a high level of nestin (red in Figure 1C).

We then tested the differentiation potential of BM- and SVZ-NSCs in vitro. Neurospheres at 5th to 10th passages were dislodged from plates, dissociated into single cells or smaller neurospheres, then transferred into poly-L-lysine precoated chamber slides and maintained in differentiation medium. After 10 to 14 days, BM- and SVZ-NSCs changed morphology and developed into neurons (NF-M+), astrocytes (GFAP+), and oligodendrocytes (MBP+) as verified by immunostaining, whereas a fraction of both types of NSCs remained undifferentiated (nestin+), indicating that BM- and SVZ-NSCs are multipotent. Neural cells that developed from BM- and SVZ-NSCs were morphologically indistinguishable (Figure 1D).

Transplantation of BM-NSCs Suppresses Ongoing EAE to a Comparable Extent as SVZ-NSCs

As shown in Figure 2A, sham-treated mice developed typical EAE, whereas both BM- and SVZ-NSCs treated mice had significantly less severe disease (P < 0.05). Although SVZ-NSCs induced a slightly quicker EAE suppression than BM-NSCs, difference was not significant. Consistent with clinical observation, mice treated with BM- or SVZ-NSCs exhibited a significantly, though slightly, reduced inflammatory infiltration than control mice (Figure 2, B–F). Similar inflammation score (Figure 2E) and comparable numbers of CNS-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and CD68+ macrophages/microglia (Figure 2F) were obtained from spinal cords of BM- and SVZ-NSC treated mice, which were all significantly lower than from sham-treated mice (all P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Both BM- and SVZ-NSCs effectively suppress chronic EAE and CNS inflammation. A: BM- and SVZ-NSCs were prepared from the same adult B6 mice. At the fifth passage, neurospheres were dissociated into single cells and washed twice with PBS. Single NSCs (1.5 × 106 cells/per mouse) were i.v. injected into MOG-immunized mice at the peak of EAE (day 22 p.i.). EAE mice that received PBS injection served as the sham control; n = 6 to 8 mice/group. Clinical EAE was scored daily by two researchers blindly according to a 0 to 5 scale. *P < 0.05 between sham-EAE and other groups. No significant differences between BM-NSCs- and SVZ-NSCs-injected groups were observed. One of three representative experiments is shown. B–F: Anti-inflammatory effects of BM- and SVZ-NSCs in the CNS. EAE mice were sacrificed two weeks p.t., and the lumbar regions of spinal cords were harvested for H&E staining to detect inflammation (B). A slight reduction of inflammatory infiltrates in the white matter of spinal cord and slightly reduced mean score of inflammation in H&E staining (E) were found in mice treated with BM- and SVZ-NSCs compared with sham-treated mice. Cellular composition of infiltrates assessed by immunostaining showed reduced numbers of CD68 (red in C), CD8 (blue in D), and CD4 (red in D) in the same areas as above in BM- and SVZ-NSC-treated mice compared with sham-treated animals. Scale bar = 50 μm in B, C, and D. Quantitative analysis of CNS-infiltrating cells is shown in F. *P < 0.05 between sham-EAE group and other groups; (n = 8 each group). ND, not detectable.

Homing of BM- and SVZ-NSCs in the CNS of EAE Mice

To assess distribution and differentiation of injected NSCs, brains and spinal cords were harvested at weeks 2, 6, and 11 p.t. after extensive perfusion. All pathology/immunohistochemistry studies were focused at standard 500 μm2 specific fields within the ventral column of the lumbar spinal cord (L3) and corpus callosum as shown previously.11,21–24 Blood vessels were identified by an endothelial marker laminin (red in Figure 3A) as described.32 At week 2 p.t., only a few transplanted GFP+ cells were found in brain parenchyma in both BM-NSCs and SVZ-NSCs groups (Figure 3, B and C), whereas most of them remained in perivascular areas of the CNS and the peripheral organs (data not shown). At week 6 p.t., most of these NSCs migrated into inflammatory foci in the CNS parenchyma, which was identified as tissues within white matter areas (eg, ventral column and corpus callosum) and far from blood vessels (Figure 3, A and C). Inflammatory foci overlapped with demyelinated foci, as identified by serial sections (data not shown). At week 11 p.t., almost all NSCs were in demyelinated foci (37 to 38 cells/mm2 in brain; Figure 3C), and only a few cells remained in perivascular areas (data not shown). EAE lesions in the brain contained twice as many transplanted NSCs as those in the spinal cord. BM-NSCs and SVZ-NSCs exhibited a similar distribution pattern (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Homing of transplanted NSCs in the CNS of EAE mice. Mice described in Figure 2A (i.v. at day 22 p.i.) were sacrificed at week 2, 6, or 11 p.t.; the brains and spinal cords were harvested for immunohistology. A: Transplanted NSCs (green) had migrated from perivascular spaces to parenchyma by six weeks p.t. (arrows). Blood vessels were stained with anti-laminin antibody (red). Scale bar = 100 μm. Quantitative analysis of NSCs that reached the parenchyma of EAE at 2, 6, and 11 weeks p.t. are shown in C, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, comparisons between two weeks p.t. and other time points; †P < 0.05, comparison between 6 and 11 weeks p.t. B: Immunostaining with anti-nestin antibody. Co-localization of GFP+ (green), nestin+ (red) cells, and DAPI+ nuclei (blue) was detected in BM- and SVZ-NSC-injected mice, demonstrating that almost all (week 2 p.t.) or part of these cells (week 11 p.t.) retained an undifferentiated phenotype (nestin+). Scale bar = 50 μm. Cells identified by arrows appear at a higher magnification in the insets (Scale bar = 15 μm). D: Quantitative analysis of transplanted GFP+ NSCs that retained nestin+. **P < 0.01; between 2 and 11 weeks p.t., n = 8 in each group.

At week 2 p.t., almost all GFP+ cells (90%) remained undifferentiated (nestin+); by 11 weeks p.t., a small portion (20%) of transplanted NSCs retained nestin expression (Figure 3, B and D). In contrast, GFP+ cells had been detected at week 2 p.t. in major organs, including liver, heart, lungs, kidneys, lymph nodes, and spleen, but had disappeared from these organs by week 11 p.t. (data not shown).

BM-NSCs Modulate Peripheral Immune Responses in Vivo and in Vitro

As transplanted NSCs stayed in the periphery for 10 to 20 days before migrating into the CNS,9,10 it is possible that these cells exerted an immunoregulatory effect in the periphery during EAE. To address this possibility, NSC-treated EAE mice were sacrificed at week 1 p.t., and spleen cells were isolated and stimulated with MOG35-55 peptide for 3 days. Compared with those from sham-treated EAE mice, culture supernatants from both BM- and SVZ-NSC-treated EAE mice displayed decreased levels of IFN-γ (P < 0.01) and IL-17 (P < 0.01), with an increased level of IL-10 in BM-NSC-treated mice (P < 0.05; Figure 4A). Similar cytokine production was observed in splenocytes isolated at week 2 p.t. (data not shown). In in vitro co-culture, both BM- and SVZ-NSCs inhibited MOG-induced IFN-γ and IL-17 production and enhanced IL-10 production of splenocytes compared with cultures without NSCs (P < 0.05, Figure 4B). No significant difference was found between splenocytes co-cultured with BM- and SVZ-NSCs. The above cytokines (IL-17, IFN-γ, and IL-10) were not detectable in supernatants of BM- and SVZ-NSCs only (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Immunomodulatory effects of BM- and SVZ-NSCs in the periphery. A:In vivo inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Splenocytes from each group of EAE mice described in Figure 2A were harvested one week p.t., cultured at 1.5 × 106 cells/ml and stimulated with MOG35-55 for 3 days. Cytokine production in supernatants was analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, comparisons between sham-treated animals and other groups (n = 6–8). B:In vitro immunomodulation. Splenocytes were isolated from MOG TCR transgenic mice, and cultured at 1.5 × 106 cells/ml in the presence of MOG35-55 peptide (10 μg/ml). BM- and SVZ-NSCs were co-cultured with these splenocytes at a ratio of 1:10 (NSCs:splenocytes). Controls included splenocytes alone or BM- and SVZ-NSCs alone in the presence of MOG35-55 peptide. Supernatants were harvested on day three to measure cytokine concentrations by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. *Comparisons between control and other groups; *P < 0.05. No IL-17, IFN-γ, or IL-10 was detected in supernatants of BM- and SVZ-NSCs. Results are mean number and SEM of five independent experiments. ND, not detectable. C: Blockade of FasL on T cells inhibited the pro-apoptotic effects of NSCs. Splenocytes were isolated from naïve MOG35-55-transgenic mice and incubated at 1.5 × 106 cells/ml with 250 ng/ml purified anti-FasL antibody (no azide/low endotoxin) for 4 days in the presence of 10 μg/ml MOG35-55, then co-cultured with single NSCs at a ratio of 10:1. After 24 hours of incubation, cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD4 antibody, annexin-V, and DAPI and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of annexin-V+ DAPI− cells among CD4+ T cells (apoptotic cells) were calculated, and mean percentage was determined from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 between T cells only and T cells co-cultured with BM- and with SVZ-NSCs. †P < 0.05 between T cells unblocked and blocked by anti-FasL antibody. Results are mean number and SEM of five independent experiments.

We then determined the possibility that BM- and SVZ-NSCs induced apoptosis of encephalitogenic T cells. Flow cytometric analysis showed a significantly higher percentage of early apoptotic CD4+ T cells in co-culture with BM- and SVZ-NSCs compared with control (T cells only; P < 0.05−0.01, Figure 4C), whereas no difference was observed between T cells co-cultured with these two types of NSCs (Figure 4C). The pro-apoptotic effect of BM- and SVZ-NSCs was partially inhibited by blocking FasL on T cells with anti-FasL antibody (P < 0.05, Figure 4C).

Both BM- and SVZ-NSCs Promote Remyelination of Demyelinated Axons

We then compared the neuro-regenerative potential of transplanted BM-NSCs with SVZ-NSCs in EAE mice. At the end of the experiment (week 11 p.t.), mice were sacrificed and brains and spinal cords were examined. Using LFB staining, rare foci of demyelination in the white matter of spinal cord were found in both BM- and SVZ-NSCs-treated-mice, with low demyelination scores. No significant difference was observed between these two NSC-treated groups. In contrast, the differences in NSC-treated groups versus EAE mice before treatment (day 22 p.i.) or sham-EAE mice (day 100 p.i.) were significant (P < 0.05 to 0.01; Figure 5, A and D).

Figure 5.

Remyelination and axonal recovery by BM- and SVZ-NSCs in chronic EAE. The lumbar regions of spinal cords of EAE mice were harvested by 11 weeks p.t. A: LFB stain showed the amelioration of demyelination in NSC-treated mice. B: Confocal image of MBP (red; for myelin) and NF-H (blue; for axon) immunostaining showed a significant increase in MBP expression and MBP+NF-H+ myelinated axons by NSC treatment. C: Electron microscopic analysis of the demyelinated lesions in spinal cords showed an increase in the percentage of myelinated axons and the presence of typical thin myelin sheaths (arrows) in NSC-treated mice, suggesting remyelination, while a large number of demyelinated axons (dash arrows) were found in EAE before i.v. and in sham-EAE, and normal thick myelin sheaths (arrowheads) were found in naïve mice. Boxed areas appear at higher magnifications in the insets. D: Mean scores of demyelination in LFB staining (n = 5). E: The amount of MBP expression in demyelinated lesions was quantified by measurement of pixel intensity of MBP immunoreactivity by using ImageJ software. F: Quantification of percentage of myelinated axons among total axons as shown in electron micrographs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 between sham-EAE group and other groups; †P < 0.05 between EAE before i.v. (at day 22 p.i.) and others. G: Mean g ratios (axon diameter divided by entire myelinated fiber diameter) were determined by using ImageJ software. At least 50 myelinated axons on the electron micrographs were measured for each mouse; five mice per group were evaluated. *P < 0.05 between naive and other groups; Scale bar = 100 μm in A; 25 μm in B; 2 μm in C; and 500 nm in the insets of C.

Myelin loss was also detected with markedly decreased MBP immunoreactivity in the ventral column (Figure 5B) and corpus callosum (Figure 6A) in EAE mice. Untreated EAE mice underwent a progressive demyelination, as evidenced by the significantly lower amount of MBP expression in sham-EAE than in EAE mice before NSC-treatment (Figure 5, A–E; P < 0.05). This progressive demyelination was reduced by BM- and SVZ-NSC-treatment (Figure 5, A–E; P < 0.05). Further, these cells had restored MBP expression at the level higher than in before-treated and sham-treated mice (P < 0.05, Figure 5E).

Figure 6.

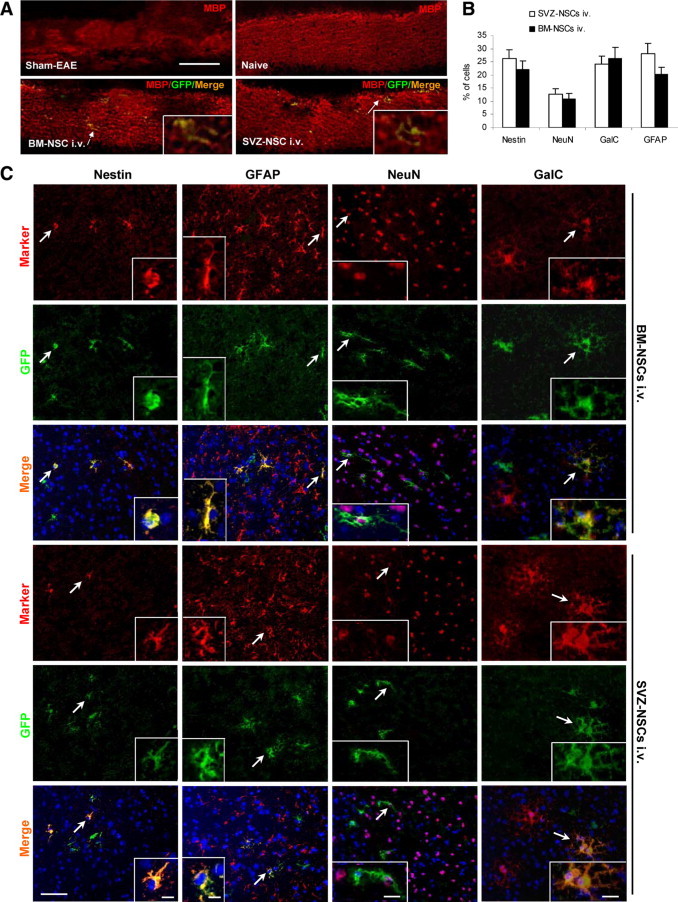

Distribution and differentiation of transplanted BM- and SVZ-NSCs in the CNS. Brains of EAE mice treated with BM- and SVZ-NSCs were harvested at week 11 p.t., and 7-μm cryosections of the brain were immunostained with anti-MBP and neural-specific antibodies. A: Multifocal demyelinated lesions were detected in the corpus callosum of EAE mice with markedly decreased MBP immunoreactivity (red). Scale bar = 100 μm. Merged cells of green (transplanted cells) and red (MBP+) designated by arrows appear at a higher magnification in the insets (Scale bar = 20 μm). B: Quantitative analysis of the differentiation of transplanted GFP+ NSCs in the CNS, as shown in (C;n = 8 in each group). C: Cells co-labeled with GFP, neural specific markers (red), and DAPI (blue) were identified as differentiated cells derived from transplanted NSCs; cells positive only for neural-specific markers (red) and DAPI (blue) were endogenous cells. GalC+: oligodendrocytes; GFAP+: astrocytes; NeuN+: neurons; nestin+: undifferentiated NSCs. Scale bar = 50 μm. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Cells designated by arrows appear at higher magnifications in the insets (Scale bar = 15 μm in the insets of nestin and GFAP; 20 μm in the insets of NeuN and GalC).

Confocal image of MBP (myelin sheaths, red) and NF-H (axons, blue) immunostaining (Figure 5B) and electron microscopic analysis (Figure 5C) of demyelinated lesions in spinal cords showed that BM- and SVZ-NSC treatment increased the percentage of MBP+NF-H+ myelinated axons among total NF-H+ axons (Figure 5F). Most of the myelinated axons in NSC-treated mice were wrapped in typical thin myelin sheaths (arrows in Figure 5C), a well-established morphological hallmark of remyelination.28,29 Greater g ratios (thinner myelin) were determined in BM- and SVZ-NSCs-treated mice than the normal g ratio in naïve mice (P < 0.05, Figure 5G), which is a characteristic of remyelination. GFP+ cells that co-expressed MBP (Figure 6A) provided direct evidence for the contribution of transplanted NSCs to remyelination. However, the majority of MBP+ cells were GFP− (Figure 6A), indicating NSC-promoted endogenous remyelination.

Differentiation of BM- and SVZ-NSCs in the CNS of EAE Mice

Co-localization of GFP+ and neural markers+ in the CNS indicated that both transplanted BM- and SVZ-NSCs had differentiated into NeuN+ neurons, GalC+ mature oligodendrocytes, and GFAP+ astrocytes at the end of the experiment (week 11 p.t.). A low proportion (23% to 26%) of GFP+ cells remained undifferentiated (nestin+; Figure 6, B and C), suggesting a comparable differentiation potential in vivo of these two types of NSCs. A similar result was observed in the white matter of spinal cord (data not shown). When brain and spinal cord sections of multiple locations were extensively examined at week 11 p.t. by immunostaining, none of the GFP+GalC+ oligodendrocytes (Figure 7A) or GFP+NeuN+ neurons (Figure 7B) were double-nucleated, which is a characteristic of fused cells. These data support neural trans-differentiation, but not fusion of BM-NSCs with endogenous neural cells.

Figure 7.

No fusion of BM-NSCs with endogenous oligodendrocytes/neurons was detected in the CNS. EAE mice treated with BM-NSCs were sacrificed at week 11 p.t. Brains were harvested, sectioned, and extensively evaluated for the evidence of cell-fusion (double or multiple nucleated) by immunostaining. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). All of the transplanted BM-NSCs (GFP+) that differentiated into GalC+ oligodendrocytes (red in A) and NeuN+ neurons (red in B) are mono-nucleated (blue). Arrows: transplanted BM-NSCs co-labeled with GFP+ (green) and GalC+ or NeuN+ (red); Arrowheads: endogenous cells labeled with GalC+ or NeuN+ (red) only. Scale bar = 25 μm in A and B. Cells in boxed areas appear at higher magnifications in the insets (Scale bar = 15 μm).

Discussion

NSCs can be isolated from the SVZ of adult mammalian CNS and can be expanded in vitro for extended periods of time without losing their proliferation or differentiation potential.33–35 NSCs transplanted either i.v. or i.c.v. are attracted by the inflammatory process to migrate into multiple demyelinating areas of the CNS, where they can differentiate into myelinating oligodendrocytes, and promote multifocal remyelination,24,36 thus having the therapeutic potential in MS. These NSCs, however, were isolated from the SVZ of adult mammalian brain tissues and are thus not accessible for clinical application with patients with MS.

Recently it has been shown that progenitor cells outside the CNS, and BM cells in particular, have the ability to generate neurons or glia in vivo and in vitro. These cells not only display a distinct neuronal shape, but also express nestin and other neural cell markers.19,37 We investigated whether BM-NSCs might be an alternative to SVZ-NSCs in the immunotherapy of EAE/MS. The following criteria have been widely used to identify NSCs9,10,12,14: (1) sphere formation; (2) nestin and/or SOX2 positive; (3) self-renewal; and most important, (4) ability to differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. Indeed, our results showed that BM- and SVZ-NSCS are similar both morphologically and phenotypically, express a similar level of NSC marker nestin, and differentiate into the three primary neural cells, which is consistent with previous reports.15,38,39 Similar to those derived from the SVZ, transplanted BM-NSCs migrated and localized into parenchyma of lesions, and differentiated in vivo into neuronal cells, and suppressed ongoing EAE. These results demonstrate the ability of adult BM cells to generate functional NSCs, thus validating this approach as an alternative source to SVZ-NSCs for clinical therapy.

A mechanism underlying NSC-induced EAE inhibition may be peripheral immunosuppression, which involves a profound bystander inhibitory effect on T cell activation and proliferation in peripheral lymphoid organs.7,40 Transplanted NSCs were transiently found in lymph nodes and spleen, where they inhibited the activation and proliferation of T cells and markedly reduced their encephalitogenicity.7,40 When NSCs were i.v. injected at an early stage of EAE (day 8 p.i.), these cells did not enter the CNS but stayed in the peripheral immune organs and inhibited EAE solely by a peripheral immunosuppressive effect.7 When NSCs were injected at peak of EAE, these cells exert immunoregulatory functions in the periphery and the inflamed sites of the CNS via induction of apoptosis of encephalitogenic cells and that interference with CNS inflammation,10 in addition to their function in cell replacement and remyelination.9,10,24 In our current study, injection of BM-NSCs and SVZ-NSCs suppressed clinical EAE, with a comparable mild reduction of CNS inflammation and decrease in IL-17 and IFN-γ production in vivo. After co-culture of NSCs with myelin-reactive T cells in vitro, we found suppressed production of IFN-γ and IL-17, enhanced production of IL-10, and enhanced apoptosis of MOG-reactive T cells. These data support a similar anti-inflammatory effect of BM-NSCs and SVZ-NSCs.7,40 Of note is that NSCs of both origins induced only a low level of IL-10 production in vitro and in vivo and exerted modest immunoregulatory effect in the periphery and the CNS of EAE mice. Consistent with this, we have shown that IL-10 transduced into SVZ-NSCs profoundly enhanced their therapeutic effect on EAE.24

The clinical effect of SVZ-NSCs on EAE has been largely attributed to the multifocal remyelination and cell repopulation induced by these cells.9,24 This result has also been observed in the present study by using BM-NSC treatment. At least three factors are involved in the BM- and SVZ-NSC-induced remyelination process. (1) Reducing autoimmune responses in the periphery and disease foci protect the CNS from further damage. Sham-treated mice exhibited a significantly higher demyelination score and lower MBP expression at day 100 p.i. than EAE mice before NSC-treatment (day 22 p.i.; Figure 5). This progressive demyelination is blocked by NSC-treatment; (2) Transplanted NSCs have the potential to differentiate into neurons and oligodendrocytes, thus promoting remyelination and axonal growth. We showed that 20% to 23% of these cells differentiated into mature oligodendrocytes (GalC+) in vivo (Figure 6). Certain transplanted NSCs (GFP+) were co-localized with MBP+ cells in CNS lesions, indicating exogenous myelinating cells. Indeed, NSCs express adhension molecules and chemokine receptors10,41 and preferably migrated into inflamed sites of the CNS.42 We have shown a comparable migration and distribution pattern of transplantaed SVZ- and BM-NSCs. However, these exogenous cells (GFP+MBP+) were only a small proportion of all MBP+ cells, and thus were not a major source for remyelination in either SVZ-NSC- or BM-NSC-treated mice. (3) The majority of MBP+ cells were GFP−, indicating endogenous myelinating cells (Figure 6A). Remyelination failure in MS/EAE may be due to an environment containing elements produced by inflammation that are intrinsically hostile to the oligodendrocyte lineage.29 Reducing autoimmune responses in the CNS should, therefore, convert the hostile environment of EAE into one supportive of endogenous remyelinating cells in EAE foci.43 Further, neuronal repopulation after NSC-treatment would be beneficial for disease recovery in EAE, as neuronal loss has also been found to be involved in MS/EAE pathogenesis.44 Together, these mechanisms would more effectively promote neuron survival, axonal growth, and remyelination in SVZ-NSC- or BM-NSC-treated mice.

To date, the transdifferentiation potential of bone marrow stem cells into neural cell types has been controversial. Neurons or glia can be derived by BM cells in vivo15,45 and in vitro,14,46 though some groups did not find this phenomenon.47,48 In the present study, we showed that BM cells did differentiate into NSCs, which, comparable to SVZ-NSCs, can differentiate into neural cells in vitro and in vivo and effectively suppress EAE. It has been found that transplantation of whole BM cells at early stage of disease effectively blocked or delayed EAE development49 but without effect at chronic stage.9,49 EAE mice treated with BM-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)16,17,50,51 showed a significantly milder disease and fewer relapses compared with control mice, with decreased inflammation infiltrates, reduced demyelination, and axonal loss. In a pilot clinical trail, autologous MSCs had been injected intrathecally to patients with MS, with a demonstrable benefit in some patients,52 indicating that BM derived multipotential cells is likely to become a useful clinical tool. The effect of whole BM cells and MSCs on EAE is mainly the result of elimination of pathogenic cells49 and interference with autoimmune responses,16,50 but not transdifferentiation into neurons or oligodendrocytes.16,50 Thus, the neural replacement and remyelination property of BM-NSCs, in addition to their immunoregulatory capacity, provides a significant advantage for these cells over MSCs and whole BM cells. Further, our extensive study showed that none of the oligodendrocytes or neurons derived from transplanted BM-NSCs were double-nucleated, a characteristic that distinguishes fused cells from transdifferentiated BM-NSCs.53–55 These results provide evidence for the transdifferentiation of BM-NSCs but not fusion, as reported previously.54,55

In conclusion, BM-NSCs suppressed EAE to a comparable extent as SVZ-NSCs via both cell replacement/remyelination and immunomodulation. Because of their autologous nature, BM-NSCs have an advantage over NSCs derived from fetus or allogenic cell lines for NSC-based therapy in that they obviate the ethical problems associated with fetal NSCs, as well as potential immunological incompatibility due to the requirement for allogenic application such as NSCs of cord blood origin.14 These properties, together with their easy accessibility, provide a solid basis for replacing SVZ-NSCs with BM-NSCs in EAE/MS therapy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Katherine Regan for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, NIH, and the Groff Foundation.

A guest editor acted as editor-in-chief for this article. No person at Thomas Jefferson University was involved in the peer review process or final disposition for this article.

Current address of Y.G.: Department of Neurology, Shanghai Changhai Hospital, Shanghai, China.

References

- 1.Greenberg BM, Calabresi PA. Future research directions in multiple sclerosis therapies. Semin Neurol. 2008;28:121–127. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1019133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hohlfeld R. Biotechnological agents for the immunotherapy of multiple sclerosis: principles, problems and perspectives. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 5):865–916. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermann A, Gastl R, Liebau S, Popa MO, Fiedler J, Boehm BO, Maisel M, Lerche H, Schwarz J, Brenner R, Storch A. Efficient generation of neural stem cell-like cells from adult human bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4411–4422. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Chu N, Hu A, Gran B, Rostami A, Zhang GX. Increased IL-23p19 expression in multiple sclerosis lesions and its induction in microglia. Brain. 2007;130:490–501. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markovic-Plese S, McFarland HF. Immunopathogenesis of the multiple sclerosis lesion. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2001;1:257–262. doi: 10.1007/s11910-001-0028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boster A, Edan G, Frohman E, Javed A, Stuve O, Tselis A, Weiner H, Weinstock-Guttman B, Khan O. Intense immunosuppression in patients with rapidly worsening multiple sclerosis: treatment guidelines for the clinician. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:173–183. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Einstein O, Fainstein N, Vaknin I, Mizrachi-Kol R, Reihartz E, Grigoriadis N, Lavon I, Baniyash M, Lassmann H, Ben-Hur T. Neural precursors attenuate autoimmune encephalomyelitis by peripheral immunosuppression. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:209–218. doi: 10.1002/ana.21033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imitola J, Khoury SJ. Neural stem cells and the future treatment of neurological diseases: raising the standard. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;438:9–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-133-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pluchino S, Quattrini A, Brambilla E, Gritti A, Salani G, Dina G, Galli R, Del Carro U, Amadio S, Bergami A, Furlan R, Comi G, Vescovi AL, Martino G. Injection of adult neurospheres induces recovery in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2003;422:688–694. doi: 10.1038/nature01552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pluchino S, Zanotti L, Rossi B, Brambilla E, Ottoboni L, Salani G, Martinello M, Cattalini A, Bergami A, Furlan R, Comi G, Constantin G, Martino G. Neurosphere-derived multipotent precursors promote neuroprotection by an immunomodulatory mechanism. Nature. 2005;436:266–271. doi: 10.1038/nature03889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J, Rostami A, Zhang GX. Cellular remyelinating therapy in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;276:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conti L, Reitano E, Cattaneo E. Neural stem cell systems: diversities and properties after transplantation in animal models of diseases. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:143–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.00009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horner PJ, Gage FH. Regenerating the damaged central nervous system. Nature. 2000;407:963–970. doi: 10.1038/35039559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabos P, Ehtesham M, Kabosova A, Black KL, Yu JS. Generation of neural progenitor cells from whole adult bone marrow. Exp Neurol. 2002;178:288–293. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonilla S, Silva A, Valdes L, Geijo E, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Martinez S. Functional neural stem cells derived from adult bone marrow. Neuroscience. 2005;133:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerdoni E, Gallo B, Casazza S, Musio S, Bonanni I, Pedemonte E, Mantegazza R, Frassoni F, Mancardi G, Pedotti R, Uccelli A. Mesenchymal stem cells effectively modulate pathogenic immune response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:219–227. doi: 10.1002/ana.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karussis D, Kassis I, Kurkalli BG, Slavin S. Immunomodulation and neuroprotection with mesenchymal bone marrow stem cells (MSCs): a proposed treatment for multiple sclerosis and other neuroimmunological/neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurol Sci. 2008;265:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Min CK, Kim BG, Park G, Cho B, Oh IH. IL-10-transduced bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can attenuate the severity of acute graft-versus-host disease after experimental allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:637–645. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song S, Song S, Zhang H, Cuevas J, Sanchez-Ramos J. Comparison of neuron-like cells derived from bone marrow stem cells to those differentiated from adult brain neural stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:747–756. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benson JM, Campbell KA, Guan Z, Gienapp IE, Stuckman SS, Forsthuber T, Whitacre CC. T-cell activation and receptor downmodulation precede deletion induced by mucosally administered antigen. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1031–1038. doi: 10.1172/JCI10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bannerman PG, Hahn A. Enhanced visualization of axonopathy in EAE using thy1-YFP transgenic mice. J Neurol Sci. 2007;260:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miron VE, Zehntner SP, Kuhlmann T, Ludwin SK, Owens T, Kennedy TE, Bedell BJ, Antel JP. Statin therapy inhibits remyelination in the central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1880–1890. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serres S, Anthony DC, Jiang Y, Broom KA, Campbell SJ, Tyler DJ, van Kasteren SI, Davis BG, Sibson NR. Systemic inflammatory response reactivates immune-mediated lesions in rat brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4820–4828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0406-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Jiang Z, Fitzgerald DC, Ma C, Yu S, Li H, Zhao Z, Li Y, Ciric B, Curtis M, Rostami A, Zhang GX. Adult neural stem cells expressing IL-10 confer potent immunomodulation and remyelination in experimental autoimmune encephalitis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3678–3691. doi: 10.1172/JCI37914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Zhang GX, Gran B, Yu S, Li J, Siglienti I, Chen X, Kamoun M, Rostami A. Induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in IL-12 receptor-beta2-deficient mice: IL-12 responsiveness is not required in the pathogenesis of inflammatory demyelination in the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2003;170:2153–2160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguirre A, Dupree JL, Mangin JM, Gallo V. A functional role for EGFR signaling in myelination and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:990–1002. doi: 10.1038/nn1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paunescu TG, Russo LM, Da Silva N, Kovacikova J, Mohebbi N, Van Hoek AN, McKee M, Wagner CA, Breton S, Brown D. Compensatory membrane expression of the V-ATPase B2 subunit isoform in renal medullary intercalated cells of B1-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1915–F1926. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00160.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stidworthy MF, Genoud S, Suter U, Mantei N, Franklin RJ. Quantifying the early stages of remyelination following cuprizone-induced demyelination. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:329–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:839–855. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park H, Jung YK, Park OJ, Lee YJ, Choi JY, Choi Y. Interaction of Fas ligand and Fas expressed on osteoclast precursors increases osteoclastogenesis. J Immunol. 2005;175:7193–7201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valverde AM, Mur C, Brownlee M, Benito M. Susceptibility to apoptosis in insulin-like growth factor-I receptor-deficient brown adipocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5101–5117. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu H, Hu F, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Borza DB, Ungvari Z, Lagamma EF, Csiszar A, Nedergaard M, Ballabh P. Maturational changes in laminin, fibronectin, collagen IV, and perlecan in germinal matrix, cortex, and white matter and effect of betamethasone. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1482–1500. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwanami A, Kaneko S, Nakamura M, Kanemura Y, Mori H, Kobayashi S, Yamasaki M, Momoshima S, Ishii H, Ando K, Tanioka Y, Tamaoki N, Nomura T, Toyama Y, Okano H. Transplantation of human neural stem cells for spinal cord injury in primates. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:182–190. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magnus T, Rao MS. Neural stem cells in inflammatory CNS diseases: mechanisms and therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:303–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nunes MC, Roy NS, Keyoung HM, Goodman RR, McKhann G, 2nd, Jiang L, Kang J, Nedergaard M, Goldman SA. Identification and isolation of multipotential neural progenitor cells from the subcortical white matter of the adult human brain. Nat Med. 2003;9:439–447. doi: 10.1038/nm837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clarke D, Frisen J. Differentiation potential of adult stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:575–580. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mezey E, Key S, Vogelsang G, Szalayova I, Lange GD, Crain B. Transplanted bone marrow generates new neurons in human brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1364–1369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mezey E, Chandross KJ, Harta G, Maki RA, McKercher SR. Turning blood into brain: cells bearing neuronal antigens generated in vivo from bone marrow. Science. 2000;290:1779–1782. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan X, Hu J, Belladonna ML, Black KL, Yu JS. Interleukin-23-expressing bone marrow-derived neural stem-like cells exhibit antitumor activity against intracranial glioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2630–2638. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ben-Hur T. Immunomodulation by neural stem cells. J Neurol Sci. 2008;265:102–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guan Y, Jiang Z, Ciric B, Rostami AM, Zhang GX. Upregulation of chemokine receptor expression by IL-10/IL-4 in adult neural stem cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;85:232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Einstein O, Grigoriadis N, Mizrachi-Kol R, Reinhartz E, Polyzoidou E, Lavon I, Milonas I, Karussis D, Abramsky O, Ben-Hur T. Transplanted neural precursor cells reduce brain inflammation to attenuate chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bettelli E, Das MP, Howard ED, Weiner HL, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. IL-10 is critical in the regulation of autoimmune encephalomyelitis as demonstrated by studies of IL-10- and IL-4-deficient and transgenic mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:3299–3306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bannerman PG, Hahn A, Ramirez S, Morley M, Bonnemann C, Yu S, Zhang GX, Rostami A, Pleasure D. Motor neuron pathology in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: studies in THY1-YFP transgenic mice. Brain. 2005;128:1877–1886. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brazelton TR, Rossi FM, Keshet GI, Blau HM. From marrow to brain: expression of neuronal phenotypes in adult mice. Science. 2000;290:1775–1779. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tropel P, Platet N, Platel JC, Noel D, Albrieux M, Benabid AL, Berger F. Functional neuronal differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2868–2876. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castro RF, Jackson KA, Goodell MA, Robertson CS, Liu H, Shine HD. Failure of bone marrow cells to transdifferentiate into neural cells in vivo. Science. 2002;297:1299. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5585.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roybon L, Ma Z, Asztely F, Fosum A, Jacobsen SE, Brundin P, Li JY. Failure of transdifferentiation of adult hematopoietic stem cells into neurons. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1594–1604. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cassiani-Ingoni R, Muraro PA, Magnus T, Reichert-Scrivner S, Schmidt J, Huh J, Quandt JA, Bratincsak A, Shahar T, Eusebi F, Sherman LS, Mattson MP, Martin R, Rao MS. Disease progression after bone marrow transplantation in a model of multiple sclerosis is associated with chronic microglial and glial progenitor response. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:637–649. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e318093f3ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zappia E, Casazza S, Pedemonte E, Benvenuto F, Bonanni I, Gerdoni E, Giunti D, Ceravolo A, Cazzanti F, Frassoni F, Mancardi G, Uccelli A. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T-cell anergy. Blood. 2005;106:1755–1761. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kassis I, Grigoriadis N, Gowda-Kurkalli B, Mizrachi-Kol R, Ben-Hur T, Slavin S, Abramsky O, Karussis D. Neuroprotection and immunomodulation with mesenchymal stem cells in chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:753–761. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slavin S, Kurkalli BG, Karussis D. The potential use of adult stem cells for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disorders. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:943–946. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ackman JB, Siddiqi F, Walikonis RS, LoTurco JJ. Fusion of microglia with pyramidal neurons after retroviral infection. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11413–11422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Fike JR, Lee HO, Pfeffer K, Lois C, Morrison SJ, Alvarez-Buylla A. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425:968–973. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weimann JM, Charlton CA, Brazelton TR, Hackman RC, Blau HM. Contribution of transplanted bone marrow cells to Purkinje neurons in human adult brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2088–2093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337659100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]