Abstract

Background

In recent years hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has emerged as a key therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). We determined the rates of HCQ use in a diverse, community-based cohort of patients with SLE and identified predictors of current HCQ use.

Methods

Patients were participants in the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Lupus Outcomes Study (LOS), an ongoing longitudinal study of patients with confirmed SLE. We examined the prevalence of HCQ use per person-year and compared baseline characteristics of users and non-users, including demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, and health-system use variables. Multiple logistic regression with generalized estimating equations was used to evaluate predictors of HCQ use.

Results

Eight hundred and eighty one patients contributed 3095person-years of data over 4 interview cycles. The prevalence of HCQ use was 55 per 100 person-years and was constant throughout the observation period. In multivariate models, the odds of HCQ use were nearly doubled among patients receiving their SLE care from a rheumatologist compared to those identifying generalists or nephrologists as their primary sources of SLE care. In addition, patients with shorter disease duration were more likely to use HCQ, even after adjusting for age and other covariates.

Conclusions

In this community-based cohort of patients, HCQ use was suboptimal. Physician specialty and disease duration were the strongest predictors of HCQ use. Patients who are not using HCQ, those with longer disease duration, and those who see non-rheumatologists for their SLE care should be targeted for quality improvement.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has emerged as a key therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1 HCQ has been shown to reduce SLE activity in two double-blind randomized clinical trials.2,3 Other, less robust, observational data suggest that HCQ may reduce the progression of lupus renal disease,4 improve lipid profiles,5 reduce the incidence of thrombotic events and diabetes, 6,7 and improve survival, even when accounting for its frequent use in patients with more mild disease.8,9,10,11 Furthermore, HCQ is inexpensive, safe and well-tolerated: only 5 to 10% of patients experience minor side effects, and these are usually gastrointestinal or cutaneous (rash). In rare cases, serious eye toxicity has been reported (<0.1% of HCQ users after 10 years of use).12 There is increasing consensus that HCQ should be used by the vast majority of SLE patients.13

HCQ use has been studied almost exclusively among patients followed by rheumatologists at tertiary care centers; rates of use ranged from 48–68%.8,9,10,14,15 One community-based study from Puerto Rico, found that 31% of SLE patients were using HCQ, but this study excluded patients who were enrolled in public insurance programs.16 To our knowledge, no other published studies have identified predictors of HCQ use or non-use in a community-based cohort of SLE patients. In this study, we aimed to determine the prevalence of HCQ use in a diverse, community-based cohort of patients with SLE in the US and to identify predictors of HCQ use.

Methods

Patients

Patients were participants in the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Lupus Outcomes Study (LOS). The LOS is an ongoing longitudinal survey of 1180 patients with physician-diagnosed SLE recruited between 2002 and 2009. Subjects eligible for this study were enrolled between 2002 and 2004 and followed through 2006. The LOS introduced the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) in the second interview year (2003). Therefore, we drew data for this study from the second through fifth consecutive years of the LOS (waves 2–5). Eight hundred and eighty seven individuals were interviewed at least once during this period. On average, 94% of eligible subjects from each wave were re-interviewed in the subsequent wave. Forty six observations were excluded because they were missing key variables.

Patients were originally recruited from academic rheumatology offices (23%), community rheumatology offices (11%), and other community-based sources (66%), such as SLE support groups, the Internet, and media advertisements. Two-thirds of the participants were residents of California while the remainder resided in 40 other US states. SLE diagnoses for all LOS participants were confirmed to meet ACR criteria by formal chart review by a rheumatologist, or trained nurse or research assistant supervised by a rheumatologist prior to entry into the cohort. All participants provided informed consent prior to the interviews. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved the study protocol.

Data

Data were collected via an annual, structured, 1-hour telephone survey conducted by trained interviewers. The survey included validated items covering the following domains: demographics and socioeconomic status, status of SLE, disability, general health and social functioning, employment, psychological and cognitive status, health care utilization, medications, and health insurance coverage.

Measures

Demographic/socioeconomic variables

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics included age at interview (in years), sex, self-reported race/ethnicity (Caucasian, Hispanic, Asian, African-American, or other/multiple), education level (less than high school, high school graduate, some college/no degree, associate degree/trade or vocational school, college graduate, advanced or professional degree), and income (annual household income at or below vs. above 125% of the federal poverty threshold for the year prior to interview).

SLE-specific variables

SLE-specific variables included duration of disease (in years), self-reported SLE flare within the 3 months prior to the interview, and disease activity over the 3 months prior to the interview as measured by the SLAQ, a validated self-report measure of SLE activity.17,18 Patients were also queried regarding any episodes of organ involvement since the time of the last interview, including specific questions about incident proteinuria or other kidney problems, hemoptysis or other lung problems, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, and stroke or myocardial infarction.

Health care utilization

The health care utilization section of the questionnaire asked participants about their medical care over the past 12 months. It included an enumeration of all health care practitioner visits by specialty. Participants were asked directly about who serves as their “main SLE doctor.” Internal medicine and family physicians were considered generalists. We created a measure of pill burden by summing the number of reported daily medications for each patient (range 0–15). In the logistic regression model, HCQ use was subtracted from this total.

Health insurance

The insurance section of the questionnaire, derived from the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey, included items regarding the type of health plan (health maintenance organization versus fee-for-service) and source of coverage, if any (employment based, individually purchased plan, Medicare, or Medicaid).19

Hydroxychloroquine and other medication use

Subjects were asked about “ever” use of multiple drugs upon entry into the study (wave 1). In subsequent interviews, they were asked about use of these drugs (waves 2–5) since the last interview, including corticosteroids (oral and intravenous), mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and biologic agents. Biologic agents were defined as any of the following: etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, or kineret. Subjects were also asked if they used antihypertensives or anticoagulants (heparin or warfarin).

The main outcome of interest was prevalent HCQ use since the time of the last interview. Respondents were defined as users if they answered “yes” to the question, “Since the time of your last interview, have you taken plaquenil, hydroxychloroquine, or chloroquine?”

Statistical analysis

Patients were followed for between 1 and 4 interview cycles and could therefore contribute up to 4 observations to the analysis. All analyses were performed by comparing the HCQ user person-years to the HCQ non-user person-years. In order to account for the multiple observations contributed by individuals in this analysis, demographic, clinical, and health system utilization characteristics of the cohort were compared using the Taylor series method for variance estimation in all bivariate statistical tests, as implemented in the survey analysis procedures in SAS 9.2.

We used multiple logistic regression to assess the association between HCQ use and various characteristics, several of which do not vary over time and were measured at study entry (e.g., date of birth, date of diagnosis, race/ethnicity) and several of which can vary year-to-year and were measured annually (e.g., education status, poverty status, physician type, and insurance status). Covariates in the model included age (by decade), ethnicity (Caucasian vs. non-Caucasian), income (below poverty vs. not below poverty), education level, insurance type, disease duration, disease activity score as measured by the SLAQ, total pill burden (excluding plaquenil), and main SLE physician (rheumatologist, nephrologist, generalist, or other). To account for multiple observations contributed by a single individual, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to determine predictors of HCQ use. SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

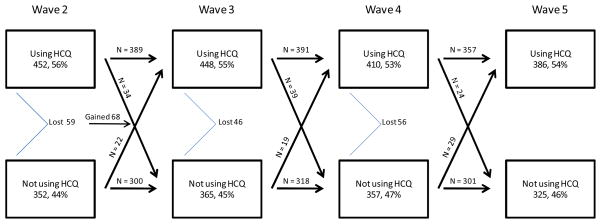

Eight hundred and eighty one individuals contributed 3095 person-years of data over 4 interview cycles in this analysis. Figure 1 describes the flow of patients through the 4 waves of interviews with regard to HCQ use. Wave 2 began with 804 patients, and 452 (56%) were HCQ users. Between waves 2 and 3, 59 subjects left the cohort and 68 additional subjects entered. Wave 3 contained 813 individuals, 448 (55%) of whom were HCQ users. Fortysix subjects left the cohort between waves 3 and 4, leaving 767 patients in wave 4. In wave 4, 410 (53%) of individuals used HCQ. Forty six subjects left the cohort between waves 4 and 5; 711 patients participated in wave 5. Overall, 55% of patients reported use of HCQ each year. Each year, approximately 7% of patients transitioned from one category of HCQ use to the other.

Figure 1. Hydroxychloroquineuse between 2004 and 2007 in the UCSF Lupus Outcomes Study.

This chart describes the flow of patients through the 4 waves of interviews with regard to HCQ use. Diagonal lines represent patients who transitioned from one category to the other from one wave to the next. Horizontal lines represent patients who remained in the same category from one wave to the next. Patients who exited the cohort (because of death or loss to follow-up) are counted at the angled line. Sixty eight patients entered the cohort after wave 2.

Table 1 describes demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables by person-years of observation. The cohort was mostly female (92%) and Caucasian (69%). HCQ users were younger compared with non-users (47.9 vs. 51.1, p < 0.0001), had shorter disease duration (13.7 vs. 16.8, p < 0.0001), and were more likely to carry employer-based insurance (60.3% vs. 51.8%, p = 0.0006). HCQ users and non-users had similar SLAQ scores (12.9 vs. 12.2, p = 0.18) although a higher proportion of HCQ users reported a recent SLE flare (51.5% vs. 41.7%, p = 0.0002). Users and non-users had similar rates of organ involvement. Users were much more likely to report having a rheumatologist as their main SLE doctor and more likely to have seen a rheumatologist at least once in the past 12 months (88% vs. 66%, p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics of 3095 person-years of observation stratified by hydroxychloroquine use in the UCSF Lupus Outcomes Study

| Using HCQ person-years = 1696 | Not using HCQ person-years = 1399 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 1558 (91.9) | 1299 (92.8) | 0.54 |

| Age (SD) | 47.9 (12.7) | 51.1 (12.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Disease duration (SD) | 13.7 (7.7) | 16.8 (9.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.99 | ||

| Caucasian | 1186 (69.9) | 965 (69.0) | |

| Asian | 140 (8.2) | 130 (9.3) | |

| Hispanic | 113 (6.7) | 98 (7.0) | |

| African-American | 152 (9.0) | 130 (9.3) | |

| Other | 105 (6.2) | 76 (5.4) | |

| Income below poverty, n (%)* | 186 (11.0) | 178 (12.7) | 0.33 |

| Principal Insurance, n (%) | 0.0006 | ||

| Employer-based | 1022 (60.3) | 724 (51.8) | |

| Medicare | 390 (23.0) | 448 (32.0) | |

| Medicaid | 104 (6.1) | 58 (4.2) | |

| Other Insurance | 156 (9.2) | 131 (9.4) | |

| No Insurance | 24 (1.4) | 38 (2.7) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.38 | ||

| High school or less | 213 (12.6) | 216 (15.4) | |

| Vocational/trade/some college | 778 (45.9) | 662 (47.3) | |

| College | 394 (23.2) | 297 (21.2) | |

| Post-graduate | 311 (18.3) | 224 (16.0) | |

| Physical function score (from SF36), mean (SD) | 59.5 (29.0) | 57.0 (30.6) | |

| SLAQ score, mean (SD) | 12.9 (7.8) | 12.2 (8.2) | |

| SLE flare within 3 months, n (%)* | 873 (51.5) | 584 (41.7) | 0.0002 |

| SLE organ involvement within 12 months, n(%) | |||

| Kidney | 492 (29.0) | 393 (28.1) | 0.57 |

| Lung | 270 (15.9) | 234 (16.7) | 0.54 |

| DVT or PE | 39 (2.3) | 43 (3.1) | 0.18 |

| Stroke or MI | 67 (4.0) | 48 (3.4) | 0.45 |

| Main SLE physician | < 0.0001 | ||

| Rheumatologist | 1431 (84.4) | 897 (64.1) | |

| Nephrologist | 35 (2.1) | 117 (8.4) | |

| Internist | 109 (6.4) | 159 (11.4) | |

| General practice | 69 (4.1) | 149 (10.6) | |

| Other | 29 (1.7) | 41 (2.9) | |

| None | 23 (1.4) | 36 (2.6) | |

| At least 1 rheumatologist visit within 12 months | 1496 (88.2) | 922 (65.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Number of daily medications, mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.4) | |

HCQ: hydroxychloroquine

SF36: Short Form (36) Health Survey

SLAQ: Systemic lupus activity score

SLE: Systemic lupus erythamatosus

n = 3025

Number of daily medications: calculated from reported medication use, including HCQ

In order to explore whether HCQ non-users were more likely to use corticosteroids or other medications, we analyzed medication use by person-year (Table 2). Sixty percent of HCQ users also used corticosteroids versus 52% of non-users (p = 0.02). HCQ users were more likely to take methotrexate compared with non-users (10.4% vs.5.4%, p = 0.0003). Other DMARD use, including the use of biologic agents, was similar between the two groups. Out of the entire cohort (3095 person-years), 69% were taking at least one DMARD (inclusive of HCQ); 13% reported using corticosteroids and no HCQ or any other DMARD. Forty percent of HCQ non-users were not taking any SLE-specific treatment (that is, they were not taking a corticosteroid or a DMARD, n = 562 person-years). This group did not differ significantly from the rest of HCQ non-users in demographics or SES. However, there was a trend towards slightly lower SLAQ scores for this group (mean, SD of 10.7, 7.6) though 36% (n = 205) reported an SLE flare within the past 3 months.

Table 2.

Medication use among 3095person-years of observation in the UCSF Lupus Outcomes Study

| All patients person-years = 3095 | Using HCQ person-years = 1696 | Not using HCQ person-years = 1399 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | ||||

| Oral steroid | 1742 (56.3) | 1009 (59.5) | 733 (52.4) | 0.01 |

| IV steroid | 238 (7.8) | 123 (7.3) | 115 (8.4) | 0.37 |

| Any systemic steroid | 1771 (57.2) | 1023 (60.3) | 748 (53.5) | 0.02 |

| DMARDs | ||||

| Cyclophosphamide (oral or intravenous) | 54 (1.8) | 31 (1.8) | 23 (1.6) | 0.73 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine | 670 (21.6) | 354 (20.9) | 316 (22.6) | 0.47 |

| Methotrexate (oral or subcutaneous) | 253 (8.2) | 177 (10.4) | 76 (5.4) | 0.0003 |

| Biologic agent | 89 (2.9) | 45 (2.6) | 44 (3.2) | 0.61 |

| Any other DMARD (excluding HCQ) | 979 (31.6) | 540 (31.8) | 439 (31.4) | 0.86 |

| No SLE-specific treatment ** | 562 (18.2) | -- | 562 (40.2) | n/a |

| Other medications | ||||

| Anti-hypertensive | 1340 (43.3) | 681 (40.2) | 659 (47.1) | 0.01 |

| Anti-coagulant | 544 (17.6) | 285 (16.8) | 259 (18.6) | 0.45 |

DMARDs: Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

HCQ: Hydroxychloroquine

No steroids, plaquenil, or other DMARD

We examined predictors of HCQ use. Univariate analyses revealed that patients over 60 years old, those with longer disease duration, and those without a rheumatologist as their main SLE physician were less likely to use HCQ (Table 3). Increasing SLAQ score and increasing pill burden were associated with increased likelihood of HCQ use. In a multivariate logistic regression model adjusting for all listed covariates, HCQ use was associated with shorter disease duration. For each additional 10 years of disease duration, there was a 27% decrease in odds of using HCQ. HCQ use was less frequent among those who obtained SLE care from non-rheumatologists compared to rheumatologists with odd ratios ranging from 0.51 (95% CI 0.31–0.84) for nephrologists to 0.68 (0.56–0.83) for those reporting no SLE physician. Sensitivity analyses using (1) number of visits to a rheumatologist as a measure of subspecialty care instead of main SLE doctor and (2) SLE flare within the past 3 months instead of SLAQ score yielded nearly identical results (data not shown).

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression model predicting hydroxychloroquine use among 3095person-years of observation in the UCSF Lupus Outcomes Study.

| Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (referent Male) | 0.94 | 0.60 | 1.47 | 0.86 | 0.56 | 1.34 |

| Age | ||||||

| < 30 | referent | referent | ||||

| 30–39 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 1.12 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 1.15 |

| 40–49 | 0.80 | 0.58 | 1.10 | 0.87 | 0.61 | 1.23 |

| 50–59 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.07 | 0.90 | 0.62 | 1.31 |

| ≥ 60 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 1.14 |

| Non-Caucasian (referent Caucasian) | 0.94 | 0.72 | 1.23 | 0.92 | 0.70 | 1.20 |

| Income below poverty line (referent above poverty) | 0.95 | 0.79 | 1.15 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 1.17 |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Employer-based | referent | referent | ||||

| Medicare | 0.89 | 0.76 | 1.04 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 1.09 |

| Medicaid | 1.03 | 0.72 | 1.48 | 1.03 | 0.70 | 1.50 |

| Other Insurance | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.09 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.11 |

| No Insurance | 0.97 | 0.69 | 1.37 | 1.14 | 0.81 | 1.63 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less | referent | referent | ||||

| Vocational/trade/some college | 1.02 | 0.81 | 1.27 | 1.02 | 0.80 | 1.29 |

| College | 0.99 | 0.75 | 1.31 | 1.01 | 0.75 | 1.36 |

| Post-graduate | 1.08 | 0.78 | 1.50 | 1.09 | 0.77 | 1.54 |

| Disease characteristics | ||||||

| Disease duration (per 10 years) | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.84 |

| SLAQ score | 1.00 | 1.02 | 6.23 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 |

| Number of daily medications* | 1.02 | 1.08 | 7.61 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 |

| Main SLE physician | ||||||

| Rheumatologist | referent | referent | ||||

| Nephrologist | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.82 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.84 |

| Generalist | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.87 |

| None | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.83 |

Number of daily medications does not include HCQ

Discussion

We examined the prevalence and predictors of HCQ use in a large, diverse cohort of confirmed SLE patients derived from the community during the period 2004–2007. Overall, the prevalence of HCQ use was 55 per 100 person-years. The odds of HCQ use were significantly higher in patients who received SLE care from rheumatologists as opposed to other specialists or generalists, however rheumatologists only prescribed HCQ in 62% of patient-years. While rheumatologist management was superior to that provided by others, there is room for improvement here as well.

Because this cohort is largely derived from community sources and only 70% of patients visited a rheumatologist on an annual basis, we expected that the rates of HCQ use might be lower than those reported from patients seen primarily at tertiary care centers. However, overall prevalence of HCQ use in this group of SLE patients was consistent with reports from referral-center-based cohorts. Fessler et al report that 56% of patients in the LUMINA cohort use HCQ, and European studies have shown prevalence of HCQ use in the 48–68% range over 10–15 year periods.9,10,14

Multivariate regression revealed that the groups of patients less likely to be users of HCQ included patients without regular rheumatologist care and those with longer disease duration. Rheumatologists are likely to be well-versed on the benefits of HCQ compared with other specialists or generalists. Patients with longer disease duration may have taken HCQ in the past and stopped because of disease quiescence, lack of perceived efficacy, or adverse effects . Unfortunately, we did not have access to the reasons for HCQ discontinuation in this study. Both physician specialty and disease duration have been reported as factors associated with low prevalence of DMARD use in both SLE patients and RA patients.16,20

Based on prior studies, we hypothesized that HCQ use might be more likely among patients with milder disease.11 Alternately, patients with more severe disease might be more likely to see subspecialists and be prescribed additional drugs. In our cohort, we found that HCQ users had slightly higher disease activity (SLAQ) scores compared with non-users. Because the SLAQ lacks questions to account for renal or hematologic disease manifestations it is possible that SLAQ scores for patients with such organ involvement were falsely low, and that SLAQ scores for patients with truly inactive disease were inflated;17 this may have biased our results toward showing no difference in disease activity between the two groups. However, we also noted that HCQ users were more likely to report an SLE flare within the past 3 months. It is unlikely that a self-report of SLE flare in the past 3 months would be differentially reported between the two groups. Furthermore, HCQ non-users were less likely to be taking corticosteroids or methotrexate compared with HCQ users. Surprisingly, a large fraction of the HCQ non-users (562 person-years of observation, 18%of all person-years contributed by 238individuals) were also not taking any SLE-specific drug (corticosteroids or DMARDs). This may reflect the personal preference of these patients to avoid any prescription medications, or perhaps very mild disease in this subgroup, although 37% of these patients reported a flare within the past 3 months.

This study has some important limitations. First, information regarding drug use was ascertained by self-report. The concordance of self-report and other measures of medication adherence (medical record review, administrative claims databases) is variable.21,22 However, one large study has shown substantial agreement between patient interview and medical record review as sources of information regarding medication use and suggests that the impact of possible misclassification on models that predict medication use is minimal.23 Second, we do not have information on reasons for HCQ non-use. It is possible that patients were prescribed HCQ in the past but were intolerant to it or refused its prescription for other reasons. Third, because of the phrasing of the interview question used in our primary analysis, patients who indicated they were users of a drug during the last 12 months may have been irregular or intermittent users. However, year-to-year persistence of HCQ use was high: over 80% of HCQ users in a wave continued to use HCQ in the subsequent wave; this is consistent with studies of other cohorts.5,24

The positive effects of HCQ on measures of disease activity and organ damage suggest that SLE patients should be using this drug in the absence of adverse effects. HCQ’s potential effects on cardiovascular risk factors including lipids, diabetes, and thrombosis and its low cost also argue that it should be a staple of SLE care. The present study indicates that current practice does not meet this goal. While patients who did not receive rheumatology care were less likely to receive HCQ, neither did many of those who did. Finally, the inverse relationship between disease duration and HCQ use as well as the physician and patient factors that contribute to this under-utilization will need to be better understood.

Our results should be confirmed and extended through further research. In addition, quality improvement programs should be initiated to expand rheumatology care for SLE patients and the use of HCQ by all specialties. Similar programs for drug utilization in diabetes and congestive heart failure provide examples of the positive impacts of such efforts.25,26

Acknowledgments

Funding: ACR/REF Physician-Scientist Development Award, National Center for Research Resources; Grant Number: 5-M01-RR-00079, Rosalind Russell Medical Research Center for Arthritis, NIH (Grant Number: R01-AR-44804), State of California Lupus Fund, Arthritis Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (Grant Number: 1-R01-HS-013893, P60-AR-053308)

References

- 1.Wallace DJ. Antimalarials---the ‘real’ advance in lupus. Lupus. 2001;10:385–87. doi: 10.1191/096120301678646092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy RA, Vilela VS, Cataldo MJ, Ramos RC, Duarte JL, Tura BR, et al. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in lupus pregnancy: double-blind and placebo-controlled study. Lupus. 2001;10:401–4. doi: 10.1191/096120301678646137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group. Tsakonas E, Joseph L, Esdaile JM, Choquette D, Senecal JL, Cividino A, et al. A longterm study of hydroxychloroquine withdrawal on exacerbations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1998;7:80–85. doi: 10.1191/096120398678919778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasitanon N, Fine DM, Haas M, Magder LS, Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine use predicts complete renal remission within 12 months among patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil therapy for membranous lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2006;15:366–70. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2313oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine use in the Baltimore Lupus Cohort: effects on lipids, glucose and thrombosis. Lupus. 1996;1:S16–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser R, Cleveland CM, Criswell LA. Risk and protective factors for thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a large, multi-ethnic cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:238–41. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.093013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasko MC, Hubert HB, Lingala VB, Elliott JR, Luggen ME, Fries JF, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and risk of diabetes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 2007;298:187–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fessler BJ, Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Roseman J, Bastian HM, Friedman AW, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: XVI. Association of hydroxychloroquine use with reduced risk of damage accrual. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1473–80. doi: 10.1002/art.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Irastorza G, Egurbide MV, Pijoan JI, Garmendia M, Villar I, Martinez-Berriotxoa A, et al. Effect of antimalarials on thrombosis and survival in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2006;15:577–83. doi: 10.1177/0961203306071872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molad Y, Gorshtein A, Wysenbeek AJ, Guedj D, Majadla R, Weinberger A, Amit-Vazina M. Protective effect of hydroxychloroquine in systemic lupus erythematosus. Prospective long-term study of an Israeli cohort. Lupus. 2002;11:356–61. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu203ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alarcón GS, McGwin G, Bertoli AM, Fessler BJ, Calvo-Alén J, Bastian HM, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine on the survival of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: data from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA L) Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1168–72. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.068676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz-Irastorza G, Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Khamashta MA. Clinical efficacy and side effects of antimalarials in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.101766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruiz-Irastorza G, Khamashta MA. Hydroxychloroquine: the cornerstone of lupus therapy. Lupus. 2008;17:271–273. doi: 10.1177/0961203307086643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández M, McGwin G, Jr, Bertoli AM, Calvo-Alén J, Vilá LM, Reveille JD, et al. Discontinuation rate and factors predictive of the use of hydroxychloroquine in LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA XL) Lupus. 2006;15:700–4. doi: 10.1177/0961203306072426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, Sebastiani GD, Gil A, Lavilla P, et al. European Working Party on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period: a comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:299–308. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000091181.93122.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molina MJ, Mayor AM, Franco AE, Morell CA, López MA, Vilá LM. Utilization of health services and prescription patterns among lupus patients followed by primary care physicians and rheumatologists in Puerto Rico. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(2 Suppl 2):S2-205–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Rivest C, Ramsey-Goldman R, Wright EA, Partridge AJ, et al. Validation of a Systemic LupusActivity Questionnaire (SLAQ) for population studies. Lupus. 2003;12:280–6. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu332oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yazdany J, Yelin EH, Panopalis P, Trupin L, Julian L, Katz PP. Validation of the systemic lupus erythematosus activity questionnaire in a large observational cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:136–43. doi: 10.1002/art.23238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen JW, Monheit AC, Beauregard KM, Cohen SB, Lefkowitz DC, Potter DE, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: a national health information resource. Inquiry. 1996–1997;33(4):373–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmajuk G, Schneeweiss S, Katz JN, Weinblatt ME, Setoguchi S, Avorn J, et al. Treatment of older adult patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis: improved but not optimal. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:928–34. doi: 10.1002/art.22890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR, Aikens JE, Lawrence JB. The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: a summary of the literature. Med Care. 2004;42(7):649–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129496.05898.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tisnado DM, Adams JL, Liu H, Damberg CL, Chen WP, Hu FA, et al. What is the concordance between the medical record and patient self-report as data sources for ambulatory care? Med Care. 2006;44:132–40. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196952.15921.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korthuis PT, Asch S, Mancewicz M, Shapiro MF, Mathews WC, Cunningham WE, et al. Measuring medication: do interviews agree with medical record and pharmacy data? Med Care. 2002;40:1270–82. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000036410.86742.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morand EF, McCloud PI, Littlejohn GO. Continuation of long-term treatment with hydroxychloroquine in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:1318–1321. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.12.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guzek J, Guzek S, Murphy K, Gallacher P, Lesneski C. Improving Diabetes Care Using a Multitiered Quality Improvement Model. Am J Med Qual. 2009 doi: 10.1177/1062860609346348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ansari M, Shlipak MG, Heidenreich PA, Van Ostaeyen D, Pohl EC, Browner WS, et al. Improving guideline adherence: a randomized trial evaluating strategies to increase beta-blocker use in heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:2799–804. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070952.08969.5B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]