Abstract

Background

Recombinant-inbred mouse strains differ in their susceptibility to Graves'-like hyperthyroidism induced by immunization with adenovirus expressing the human thyrotropin (TSH) receptor. Because one genetic component contributing to this susceptibility is altered thyroid sensitivity to TSH receptor agonist stimulation, we wished to quantify thyroid responsiveness to TSH. For such studies, it is necessary to suppress endogenous TSH by administering L-3,5,3′-triiodothyronine (L-T3), with the subsequent decrease in serum thyroxine (T4) reflecting endogenous TSH suppression. Our two objectives were to assess in different inbred strains of mice (i) the extent of serum T4 suppression after L-T3 administration and (ii) the magnitude of serum T4 increase induced by TSH.

Methods

Mice were tail-bled to establish baseline-serum T4 before L-T3 administration. We initially employed a protocol of L-T3-supplemented drinking water for 7 days. In subsequent experiments, we injected L-T3 intraperitoneally (i.p.) daily for 3 days. Mice were then injected i.p. with bovine TSH (10 mU) and euthanized 5 hours later. Serum T4 was assayed before L-T3 administration, and before and after TSH injection. In some experiments, serum T3 and estradiol were measured in pooled sera.

Results

Oral L-T3 (3 or 5 μg/mL) suppressed serum T4 levels by 26%–64% in female BALB/c mice but >95% in males. T4 suppression in female B6 mice ranged from 0% to 90%. In C3H mice, L-T3 at 3 μg/mL was ineffective but 5 μg/mL achieved >80% serum T4 reduction. Unlike inbred mice, in outbred CF1 mice the same protocol was more effective: 83% in females and 100% suppression in males. The degree of T4 suppression was unrelated to baseline T4, T3, or estradiol, but was related to mouse weight and postmortem T3, with greater suppression in larger mice (outbred CF1 animals and inbred males). Among females with serum T4 suppression >80%, the increase in serum T4 after TSH injection was greater for BALB/c and C3H versus B6 mice. Moreover, the T4 increment was higher in female than in male BALB/c.

Conclusions

Our data provide important, practical information for future in vivo studies in inbred mice: we recommend that responses to TSH be performed in female animals injected with L-T3 i.p. to suppress baseline T4.

Introduction

Graves'-like hyperthyroidism can be induced in susceptible mouse strains like BALB/c and C3H/He by immunization with adenovirus expressing the human thyrotropin receptor (TSHR) A-subunit (1–4). Mice of the C57BL/6 (B6) strain develop TSHR antibodies but rarely become hyperthyroid (1,5). Studies in recombinant-inbred mice derived from the resistant B6 strain crossed to hyperthyroid susceptible BALB/c (or C3H/He) mice reveal that chromosomes and loci linked to development of hyperthyroidism differ from those linked to induction of TSHR antibodies (4,6). Moreover, different mouse strains develop antibodies with preferential recognition of the human or the mouse TSHR (7,8). Because of such TSHR antibody diversity, it is difficult to distinguish between the parameters controlling antibody generation versus the factors involved in controlling thyroid sensitivity to stimulation.

One approach to assess thyroid sensitivity is to challenge different mouse strains by in vivo injection of a defined TSH dose and measuring the increase in serum thyroxine (T4). However, to do so it is necessary to rest the thyroid and suppress serum T4 levels by inhibiting endogenous TSH secretion. We describe herein extensive studies to attain this goal using previously reported protocols. Because of the importance of establishing a serum T4 baseline before TSH injection, we considered supplementing the drinking water with triiodothyronine (T3) (9) to be the preferable approach. Repeated intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of T3, as performed in rats (10) and mice (11,12), compress the protocol period and subject small animals to multiple injections and relatively large blood drawings within a relatively short period. Surprisingly, we observed that, unlike T3 injections, the efficacy of T3 administered in water to suppress serum T4 varied among different mouse strains and was sex dependent.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains

Mice aged 6–8 weeks of the following strains were studied: inbred BALB/cJ, C57BL/6J, C3H/HeJ (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), and outbred CF1 (Charles River Laboratories International, Inc., Wilmington, MA). We also used wild-type siblings of TSHR A-subunit transgenics (13) bred at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center by crossing (11 generations) to BALB/cJ (Jackson Laboratory). For simplification, in figure legends the mouse strains are abbreviated BALB, B6, C3H, and CF1. Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed with the highest standards of care in a pathogen-free facility.

T3-induced suppression of T4 and TSH stimulation

L-3,5,3′-triiodothyronine (L-T3) for drinking water was prepared as described by East-Palmer et al. (9). Ten milligrams L-T3 (T6397 or, for some studies, T67407; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 5 mL 0.1 N NaOH; this stock was diluted with tap water to give final concentrations of 3.0 μg/mL (or 5 μg/mL) and the pH adjusted to 7.0–7.5. Mice were provided with one batch of L-T3 water for the first 2 days. Thereafter, including the final day, fresh L-T3 water was prepared daily. For i.p. injections, 2 mg L-T3 (T6397; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 1 mL 0.1 N NaOH, diluted 1: 20 (0.2% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline) and the pH adjusted to 7.4; 0.1 mL of this solution (containing 5 μg L-T3) was injected.

All mice were weighed before L-T3 administration. For most studies, L-T3 was provided in the drinking water following the protocol of East-Palmer et al. (9) (Fig. 1A). This protocol involved tail bleeding the mice on day 0 to obtain baseline values followed by provision of drinking water supplemented with L-T3 (3 μg/mL) on days 1–7. On day 6, tail bleeding was performed to determine the extent of serum T4 suppression. On day 7, i.p. injection of bovine TSH (bTSH; 10 mU; Sigma-Aldrich) was performed with euthanasia 5 hours later.

FIG. 1.

Schedules for L-3,5,3′-triiodothyronine (L-T3) administration to suppress baseline thyroxine (T4) before injecting bovine thyrotropin (TSH) (10 mU) to induce T4 secretion. (A) L-T3 administered in drinking water according to East-Palmer et al. (9). (B) L-T3 injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) as described by Maia et al. (11).

In an alternative approach, some BALB/c mice received L-T3 i.p. as described by Maia et al. (11) (Fig. 1B). On day 0, tail bleeding to measure baseline values was performed. On days 1, 2, and 3, injection of L-T3 (5 μg) each morning was performed. On the afternoon of day 3, blood was drawn to determine the degree of suppression for the serum T4 baseline, and on day 4, i.p. injection of bTSH (10 mU) was performed followed by euthanasia 5 hours later. The time lapse between bTSH injection and euthanasia was guided by the experiments of East-Palmer et al. (9) in which T4 release was maximal after 4–8 hours.

Serum T4, T3, and estradiol

Serum levels of total T4, total T3, and estradiol were determined by radioimmunoassays. T4 was measured in sera from individual mice (25 μL per mouse; “Coat-a-Count total T4” kit; Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA). Standards for the T4 assay ranged from 1 to 24 μg/dL (sensitivity 0.25 μg/dL). Importantly, for each set of mice, sera for all time intervals (baseline, after L-T3 treatment, and at postmortem after bTSH injection) were tested in the same assay. Values are reported as μg/dL and as T4-released (the difference between the T3-suppressed baseline and after TSH challenge). The percentage of T4 suppression (after L-T3 treatment) was calculated as follows: (T4 at baseline −T4 after L-T3)/T4 at baseline × 100.

Because total T3 measurement requires a larger volume of serum (50 μL, for the Coat-a-Count total T3 radioimmunoassay kit from Diagnostic Products Corporation), tests were performed on sera pooled for the appropriate time intervals and reported as ng/dL. Standards for the T3 assay ranged from 20 to 600 ng T3/dL (sensitivity 7 ng/dL). All T3 data were obtained using a single kit. Estradiol was measured by a radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc., Webster, TX). The assay was modified to use 50 μL (rather than 200 μL) of mouse serum added to 150 μL of Standard A containing 0 pg/mL estradiol (provided in the kit). Estradiol standards (1–150 pg/mL) were diluted in the same way, and, after correction for dilution, the data are reported as pg/mL estradiol. Postmortem sera were analyzed individually for estradiol.

Statistical analysis

Most experiments were performed in groups of four to five mice (occasionally fewer, as specified in the figures). For one analysis, we used the means for all L-T3 treated mice in each experiment. Differences between groups were tested by Student's t-test or Rank Sum test as appropriate (SigmaStat; Jandel Scientific Software, San Rafael, CA).

Results

Variable and/or low level serum T4 suppression by L-T3 in drinking water

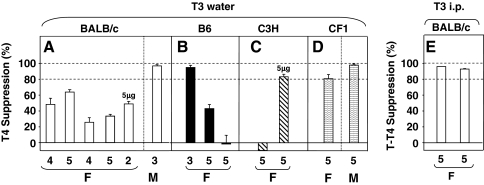

Suppression of serum T4 by L-T3 in drinking water (3 μg/mL) varied in female BALB/c mice, ranging from 26% to 64%, but reached >95% in males (Fig. 2A). Exposure to a higher L-T3 dose (5 μg/mL) did not enhance suppression in two female mice of this strain. In contrast, >90% suppression was achieved in the first study of female B6 mice but in two subsequent experiments much lower or no suppression was observed (Fig. 2B). In C3H mice, L-T3 at 3 μg/mL was ineffective but a higher dose (5 μg/mL) achieved over 80% reduction in serum T4 (Fig. 2C). During the course of these studies in inbred mice, we performed the same protocol in CF1 outbred mice and confirmed previous observations of nearly 100% suppression in males (9), although only 83% suppression in females (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Suppression of T4 by L-T3 in drinking water (A–D) or injected i.p. (E). Mice studied were BALB/c, B6, and C3H/He (C3H), all inbred, and outbred CF1 mice. As described in the Materials and Methods section, suppression was calculated as the decrease from baseline T4 expressed as a percentage of baseline T4. The data are shown as a bar graph, where the bars indicate the mean suppression values for each experiment; error bars are standard error of the mean (where n = 3–5) or the standard deviation (where n = 2). The number of mice in each experimental group is shown below their respective bars; females are indicated by F, and males by M. All mice were given drinking water with 3 μg/mL L-T3 except for two BALB/c and five C3H animals that were provided with 5 μg/mL (as indicated).

Suppression of serum T4 by L-T3 injected i.p.

Because in all BALB/c females L-T3 in water incompletely suppressed serum T4, we tested the outcome of L-T3 injected i.p. by an investigator trained to perform this procedure without anesthesia. In two separate experiments (each involving five mice) and without mortality, L-T3 injected i.p. suppressed T4 by >90% in all female BALB/c mice far more effectively than when drinking water was supplemented with T3 (Fig. 2E vs. Fig. 2A).

Basis for the variability in serum T4 suppression by L-T3 in drinking water

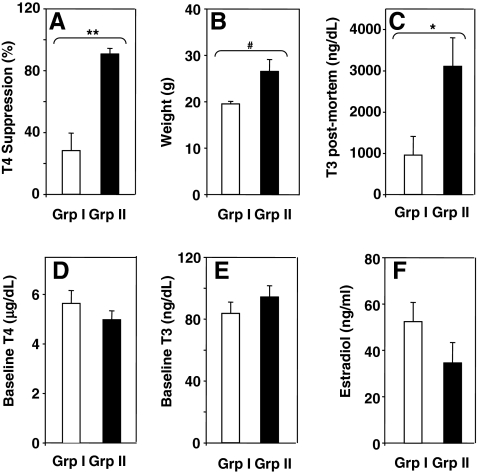

The poor and variable outcome of oral L-T3 suppression of serum T4 was unrelated to the temporal sequence in which the studies were performed or to temperature fluctuations in the facility in which the mice were housed (not shown). Next, we investigated the possible contribution of the following parameters in determining variable outcomes of L-T3 in drinking water: (i) mouse weight, (ii) baseline serum T4 or T3 before T3 addition to the drinking water, and (iii) serum T3 postmortem. In addition, because East-Palmer et al. (9) had studied male mice and commented on possible interference by estrogens, we measured serum estradiol. For all mouse strains and genders, the means for these parameters were subdivided into experiments in which we observed either <80% serum T4 suppression (group I) or >80% suppression (group II). By definition because of these selection criteria, the difference in suppression between groups I and II was statistically significant (Fig. 3A). Mice in group II were significantly heavier and had higher T3 levels postmortem than mice in group I (Fig. 3B, C). However, there were no significant differences between groups I and II for baseline (pre-T3 administration) serum T4, T3, or estradiol (Fig. 3D–F). These findings indicate that more effective suppression occurs in mice that are larger (males rather than females and in the CF1 strain of either gender) and that have a higher overall L-T3 intake as assessed from postmortem serum T3 levels.

FIG. 3.

The magnitude of suppression induced by L-T3 in water is related to mouse weight and postmortem T3 (A–C) but not to baseline T4, T3, or estradiol (D–F). From the mean suppression values for BALB/c, C57BL/6, C3H/He, and CF1 mice (bar graphs in Fig. 2), the data were subdivided into two groups: group I, <80% suppression; group II, >80% suppression. Number of animals in each group: group I, n = 8; group II, n = 5. Values significantly higher for group II versus group I: **p < 0.002 and *p < 0.02 (t-test) and #p = 0.019 (rank sum test).

Magnitude of T4 release in response to TSH

To assess factors influencing the serum T4 response to TSH stimulation, it was necessary to restrict the analysis to experiments in which T3 pretreatment substantially suppressed serum T4 levels (>80% reduction from baseline) (see Fig. 2). The rationale underlying this selection was that in experiments in which serum T4 levels were suppressed poorly, the T4 response to TSH injection was minimal or absent. For analysis, irrespective of the route of L-T3 administration, we subdivided the data into two categories, serum T4 suppression >90% versus suppression of >80% but <90% before TSH injection. In these two categories, we compared the baseline serum T4 values before T3 suppression (Fig. 4A, B), the serum T4 levels pre- and post-TSH stimulation (Fig. 4C, D), and the net increase in serum T4 in response to TSH stimulation (Fig. 4E, F). In these comparisons, all mice were injected with 10 mU of TSH, the higher of two doses previously reported in a study of differences between wild-type mice and animals with transcription-factor 1 insufficiency (12).

FIG. 4.

T4 release after L-T3-induced suppression >90% (A, C, E) and <80% (B, D, F) for inbred (BALB/c, B6, and C3H) and outbred (CF1) mice. (A, B) Baseline T3 before T3, serum T4 before (first bar) and after (second bar) TSH injection; (E, F) net increase in T4 after TSH injection (for calculation, see the Materials and Methods section). L-T3 administration by water (w) or i.p. injection is indicated; the number of mice in each experiment is in parentheses. Values significantly different: (C, D) **p < 0.001; *p = 0.003 (paired t-tests); (E) #p < 0.036 BALB(F) versus B6(F) (rank sum test); **p = 0.002 BALB(F) versus BALB(M) (t-test).

As anticipated, baseline serum T4 values before T3 suppression varied moderately among different mouse strains, but there was no discernable relationship between these values (Fig. 4A, B) and the degree of suppression by T3 administration (Fig. 4C, D; left bars in each panel). TSH injection significantly increased serum T4 levels in some (female BALB/c, male and female outbred CF1), but not other (female B6, male CF1 and female C3H), mouse strains (Fig. 4C, D). The net increases in serum T4 levels after TSH stimulation were similar in most groups compared with female BALB/c mice, except for male BALB/c and female B6 mice, which had significantly lower increments (Fig. 4E, F). The degree, or efficacy, of serum T4 suppression by T3 administration did not influence the net serum T4 response to TSH stimulation. For example, the increment in serum T4 in female BALB/c mice was significantly greater than in female B6 and male BALB/c mice (Fig. 4E) although in all three groups L-T3 treatment suppressed serum T4 levels by >90%. Conversely, C3H and CF1 females were slightly less well suppressed (80%–90%) yet their net increments in serum T4 (Fig. 4F) were not significantly different from some strains (female BALB/c and male CF1) that had >90% T4 suppression. Overall, therefore, the critical factors that determine T4 suppression after L-T3 administration and T4 release in response to TSH appear to involve mouse strain and gender.

Discussion

In vivo studies on thyrocyte responses to stimulation are subject to greater variability than similar studies performed in vitro, such as with cultured cells. Establishing a baseline for such studies is a critical requirement for evaluating the response to stimulation. The thyroid response to TSH stimulation in vivo can be assessed by measuring the increment in serum T4 levels. However, baseline serum T4 levels can vary widely among mouse strains (14) and to a lesser extent among individuals within a strain. Therefore, to quantify the serum T4 response to TSH stimulation, as well as to maximize this response, it is necessary to suppress the basal T4 level to a very low level, but not for a prolonged period that will result in thyroid atrophy. For this purpose, previous studies have administered L-T3 either in the drinking water (9) or by injection (11). We initially elected the former approach to avoid the number of manipulations required in a short-term protocol for mice, in particular, multiple tail bleeding for serum T4 measurements.

Gender differences in serum T4 levels have been reported for mice (14). Moreover, we normally induce Graves'-like hyperthyroidism by TSHR A-subunit-adenovirus immunization in female mice (1,2,4–6). We, therefore, initially studied female mice of different strains. However, after we observed variable and inadequate suppression of serum T4 on administering water supplemented with T3, we also tested male mice, for the following reason. Although not strongly emphasized, East-Palmer et al. (9) confined their studies to male mice to avoid the modulating effects of estrogens on TSH secretion in rodents (15). Indeed, with T3-supplemented drinking water, we confirmed their observation of >95% suppression of serum T4 in CF1 males and observed comparable suppression in male (but not female) BALB/c mice. Similarly, complete T4 suppression was achieved by administering L-T3 in water to male mice of both an outbred strain (CF-1 BR) and an inbred strain (BALB/c) (16,17).

To explore the basis for the variable outcome of L-T3 administration in drinking water, we considered possible contributions by mouse weight, baseline serum T4 and T3 levels, the serum T3 level attained before TSH administration, serum T3 at postmortem, and, because of the aforementioned effect of estrogens on TSH secretion in rodents (15), serum estradiol levels. We report that L-T3 intake from water is most effective in large mice such as outbred CF1, and particularly in male rather than female inbred strains (the latter gender tend to be smaller). Stability of T3 in water is an important consideration. However, the mouse weight and gender difference that we observed speak against such an influence. In addition, as recommended (9), for the final 5 days of the protocol (Fig. 1) we provided mice with fresh L-T3 water daily. Finally, in experiments to assess thyroid sensitivity to TSH injection after adequate (>80%) suppression of serum T4 levels, we found that the increment in serum T4 was greater in female BALB/c and C3H mice than in female C57BL/6 mice. Moreover, the response to TSH in female BALB/c mice was greater than that in males of the same strain.

In summary, our data provide important and practical information for future in vivo studies on inbred mice. L-T3 water administration does not effectively maximize serum T4 suppression, except in males. On the basis of our findings, we recommend that responses to TSH in inbred mice (such as very expensive recombinant inbred strains) should be performed in female mice injected with L-T3 intraperitoneally to suppress baseline T4.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK54684 (S.M.M.) and DK19289 (B.R). The authors are also grateful to Dr. Boris Catz, Los Angeles, CA, for his contributions.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Nagayama Y. Kita-Furuyama M. Ando T. Nakao K. Mizuguchi H. Hayakawa T. Eguchi K. Niwa M. A novel murine model of Graves' hyperthyroidism with intramuscular injection of adenovirus expressing the thyrotropin receptor. J Immunol. 2002;168:2789–2794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen C-R. Pichurin P. Nagayama Y. Latrofa F. Rapoport B. McLachlan SM. The thyrotropin receptor autoantigen in Graves' disease is the culprit as well as the victim. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1897–1904. doi: 10.1172/JCI17069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seetharamaiah GS. Land KJ. Differential Susceptibility of BALB/c and BALB/cBy mice to Graves' hyperthyroidism. Thyroid. 2006;16:651–658. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLachlan SM. Aliesky HA. Pichurin PN. Chen C-R. Williams RW. Rapoport B. Shared and unique susceptibility genes in a mouse model of Graves' disease determined in BXH and CXB recombinant inbred mice. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2001–2009. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CR. Aliesky H. Pichurin PN. Nagayama Y. McLachlan SM. Rapoport B. Susceptibility rather than resistance to hyperthyroidism is dominant in a thyrotropin receptor adenovirus-induced animal model of Graves' disease as revealed by BALB/c-C57BL/6 hybrid mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4927–4933. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aliesky HA. Pichurin PN. Chen CR. Williams RW. Rapoport B. McLachlan SM. Probing the genetic basis for thyrotropin receptor antibodies and hyperthyroidism in immunized CXB recombinant inbred mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2789–2800. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misharin A. Hewison M. Chen C-R. Lagishetty V. Aliesky HA. Mizutori Y. Rapoport B. McLachlan SM. Vitamin D deficiency modulates Graves' hyperthyroidism induced in BALB/c mice by thyrotropin receptor immunization. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1051–1060. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rapoport B. Williams RW. Chen C-R. McLachlan SM. Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region genes contribute to the induction of thyroid stimulating antibodies in recombinant inbred mice. Genes Immun. 2010;3:254–263. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.East-Palmer J. Szkudlinski MW. Lee J. Thotakura NR. Weintraub BD. A novel, nonradioactive in vivo bioassay of thyrotropin (TSH) Thyroid. 1995;5:55–59. doi: 10.1089/thy.1995.5.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moeller LC. Alonso M. Liao X. Broach V. Dumitrescu A. Van Sande J. Montanelli L. Skjei S. Goodwin C. Grasberger H. Refetoff S. Weiss RE. Pituitary-thyroid setpoint and thyrotropin receptor expression in consomic rats. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4727–4733. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maia AL. Kieffer JD. Harney JW. Larsen PR. Effect of 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine (T3) administration on dio1 gene expression and T3 metabolism in normal and type 1 deiodinase-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4842–4849. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.11.7588215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moeller LC. Kimura S. Kusakabe T. Liao XH. Van Sande J. Refetoff S. Hypothyroidism in thyroid transcription factor 1 haploinsufficiency is caused by reduced expression of the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2295–2302. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pichurin PN. Chen C-R. Chazenbalk GD. Aliesky H. Pham N. Rapoport B. McLachlan SM. Targeted expression of the human thyrotropin receptor A-subunit to the mouse thyroid: Insight into overcoming the lack of response to A-subunit adenovirus immunization. J Immunol. 2006;176:668–676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohlenz J. Maqueem A. Cua K. Weiss RE. Van Sande J. Refetoff S. Improved radioimmunoassay for measurement of mouse thyrotropin in serum: strain differences in thyrotropin concentration and thyrotroph sensitivity to thyroid hormone. Thyroid. 1999;9:1265–1271. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donda A. Reymond F. Rey F. Lemarchand-Beraud T. Sex steroids modulate the pituitary parameters involved in the regulation of TSH secretion in the rat. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1990;122:577–584. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1220577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colzani RM. Alex S. Fang SL. Braverman LE. Emerson CH. The effect of recombinant human thyrotropin (rhTSH) on thyroid function in mice and rats. Thyroid. 1998;8:797–801. doi: 10.1089/thy.1998.8.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azzam N. Bar-Shalom R. Kraiem Z. Fares F. Human thyrotropin (TSH) variants designed by site-directed mutagenesis block TSH activity in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2845–2850. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]