Abstract

We developed a decellularized murine lung matrix bioreactor system that could be used to evaluate the potential of stem cells to regenerate lung tissue. Lungs from 2–3-month-old C57BL/6 female mice were excised en bloc with the trachea and heart, and decellularized with sequential solutions of distilled water, detergents, NaCl, and porcine pancreatic DNase. The remaining matrix was cannulated and suspended in small airway growth medium, attached to a ventilator to simulate normal, murine breathing-induced stretch. After 7 days in an incubator, lung matrices were analyzed histologically. Scanning electron microscopy and histochemical staining demonstrated that the pulmonary matrix was intact and that the geographic placement of the proximal and distal airways, alveoli and vessels, and the basement membrane of these structures all remained intact. Decellularization was confirmed by the absence of nuclear 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining and negative polymerase chain reaction for genomic DNA. Collagen content was maintained at normal levels. Elastin, laminin, and glycosaminglycans were also present, although at lower levels compared to nondecellularized lungs. The decellularized lung matrix bioreactor was capable of supporting growth of fetal alveolar type II cells. Analysis of day 7 cryosections of fetal-cell-injected lung matrices showed pro-Sp-C, cytokeratin 18, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-positive cells lining alveolar areas that appeared to be attached to the matrix. These data illustrate the potential of using decellularized lungs as a natural three-dimensional bioengineering matrix as well as provide a model for the study of lung regeneration from pulmonary stem cells.

Introduction

Matrix- and/or cell-based therapies for lung diseases lag far behind other fields.1 However, since the report of the first implanted bioengineered upper airway tissue,2 interest in bioengineering other parts of the lung for lung repair and transplant has grown. Lung transplantation is usually the only option for patients with irreversible structural lung damage such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, primary pulmonary arterial hypertension, advanced stages of interstitial lung disease and cystic fibrosis, and α-1-antitrypsin deficiency.3 Major obstacles that have limited the success of lung transplantation4–7 include the paucity of lung organ donors and obliterative bronchiolitis,8,9 which can occur as a result of an alloimmune response due to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antigen disparities between the donor and the recipient. Encouragingly, cellular therapies for lung diseases have gained interest, but have been hindered by the lack of a suitable in vitro assay system by which to evaluate lung progenitor or reparative cells for their differentiative, regenerative, or reparative capacities.1

Several attempts have been made to bioengineer lung-like tissues using artificial scaffolds on which to grow lung cells, but these only crudely simulate the complexity of the lungs. For example, artificial scaffolds cannot replicate the branching or the composition, arrangement, and stretch of the extracellular matrix (ECM) that is juxtaposed between the epithelial layer that is exposed to air and the vascular endothelium that lines the conduits for the blood that gets reoxygenated.

Over 60 different cell types can be found in the lungs, excluding the circulatory cells, that represent a diversity of functions, including sensory, secretory, mechanical, and transport.10,11 About 65% of the total lung tissue area is in the alveolar regions.12 Approximately 12%–15% of alveolar tissue and almost 50% of the nonalveolar tissue is noncellular, that is, ECM. The ECM and basement membrane support and/or surround parenchymal cells. ECM is composed of structural proteins such as collagen and elastin, specialized proteins such as fibronectin and laminin, and high-molecular-weight proteoglycans complexed to glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Most of these components, the principal fiber of which is collagen, are produced by fibroblasts. Collagen and elastin fibers provide strength and elasticity, while laminin and heparan sulfate proteoglycan induce epithelial cell polarization and lumen formation.13 Alveolar type II (ATII) cell morphology and function is dependent on direct contact with fibroblasts and collagen fibrils.14

Several synthetic materials have been utilized in experimentation with lung tissue engineering. Degradable matrices made of polymers, including polyglycolic acid,15 pluronic F-127,16 and poly-lactic acids,17 can be produced with a wide range of mechanical and chemical properties, but they do not approximate the composition of a natural matrix. Further, such biomaterials do not support lung epithelial development when implanted in vivo.16 Manufactured scaffolds have been made of natural materials such as collagen,18,19 collagen with GAGs,20 basement membrane proteins (Matrigel),17,21 and compressed porcine skin gelatin (Gelfoam).22 These manufactured scaffolds are limited by their inadequate mechanical properties, variable degradation rates,23 and inability to precisely approximate the three-dimensional (3D) complexity of the lung, although they are superior to synthetic polymer scaffolds in supporting lung epithelial development and vascularization particularly when preloaded with fibroblast growth factors.21,22

To date, the only demonstration of using an intact decellularized parenchymal organ to recreate a functional organ is that of Taylor and co-workers, who used perfusion–decellularization (i.e., infusion of detergents through the vasculature) to create a natural 3D heart matrix that was recellularized with cardiomyocytes. The recellularized heart matrix subsequently contracted rhythmically resulting in a beating organ.24

Since the mortality due to structural lung diseases is high, development of new sources of transplantable lung tissue, preferably those that will not be targets of rejection, is needed. The use of decellularized whole lung as a matrix should allow for proper architectural and geographical arrangement of infused cells on either side of the matrix components ultimately resulting in gas exchange through the air–liquid interface. We show in this article that mouse lungs can successfully be decellularized while maintaining ECM in the correct geospatial branching pattern even after prolonged ventilation. Fetal lung cells can successfully be infused and cultured in decellularized, ventilated lungs. Therefore, our new lung bioreactor system is amenable to evaluation of the potential of lung progenitors to rebuild the lung as well as to the study of cellular interactions in the lung in its own matrix.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male and female C57BL/6 (termed B6) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, housed in microisolator cages in the Specific Pathogen-Free facility of the University of Minnesota, and cared for according to the Research Animal Resources guidelines of our institution. Protocols involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Lungs from mice aged 8–12 weeks were used as a source of lungs for decellularization. In addition, mice were bred to generate fetuses of gestation day 17 (timed after appearance of vaginal plugs) as a source of fetal lung cells for recellularization experiments.

Lung decellularization and bioreactor setup

Lungs from 2–3-month-old C57BL/6 female mice were excised en bloc with the trachea and heart, and exsanguinated via the right ventricle with saline. The heart was kept attached to better maintain overall gross configuration of the lungs in the bioreactor system. A previously described method for decellularizing human lung fragments25 was adapted for use on whole mouse lungs. The lungs were infused through the trachea and right ventricle with sequential solutions of distilled water and detergents (Triton X-100, Na deoxycholate) to lyse cells and remove insoluble cellular material. Lungs were then incubated with NaCl and porcine pancreatic DNase to lyse residual nuclei and DNA, respectively, followed by a final rinse with distilled water. The new protocol is described in detail in Table 1. The main modifications to the method described by the Madri group25 are the perfusion of solutions through the trachea and right heart ventricle instead of simple soaking of tissue fragments. The attachment of a ventilator after suspension of the matrix in the bioreactor system, to ventilate the lung and confer mechanical stretch, has not been described before for decellularized lung. All manipulations of matrix, cannula attachments, and subsequent cell infusions were done using aseptic techniques in laminar flow hoods to prevent contamination. Ventilation via the trachea introduced room air, that is, 20% oxygen, while the medium in the flask was exposed to a conventional gas mix introduced into the incubator, that is, 5% CO2.

Table 1.

Decellularization and Lung Bioreactor System Protocol

| 1. Euthanize mouse with lethal injection of Nembutal. |

| 2. Cut skin below sternum and pull skin back. Cut skin up to the chin. Cut through the peritoneum and then the diaphragm. Remove salivary glands and membrane around trachea. Cut up both sides of rib cage and remove to expose thoracic cavity. |

| 3. Perfuse the lungs by injecting 3 cc of DI solution into the right ventricle of the heart. |

| 4. Fill 3-cc syringe with DI solution and attach a 19-gauge needle. Insert needle into trachea and secure with silk suture. Inflate lungs with DI solution. Immediately after removing needle, tighten suture to contain DI solution in lungs. |

| 5. Remove heart and lungs en bloc. Remove the thymus. |

| All the following rinses and washes are done using a 3-cc syringe and a 19-gauge needle in a sterile six-well plate: |

| 6. Place lungs into DI solution and incubate for 1 h at 4°C. |

| 7. Remove lungs from DI solution. Inject five rinses of 3 cc of DI solution through the trachea and five 3-cc rinses through the right ventricle. Remove syringe after each injection to allow solution to come out on its own due to recoil of the lung. |

| 8. Inject 3 cc of Triton solution through the same hole in the trachea and 3 cc into the right ventricle. Incubate for 24 h at 4°C. |

| 9. Remove lungs from Triton solution and repeat rinses from step 7. |

| 10. Inject 3 cc of deoxycholate solution through the same hole in the trachea and 3 cc into the right ventricle. Incubate for 24 h at 4°C. |

| 11. Remove lungs from deoxycholate solution and repeat rinses from step 7. |

| 12. Inject 3 cc of NaCl solution through the same hole in the trachea and 3 cc into the right ventricle. Incubate for 1 h at room temperature. |

| 13. Remove lungs from NaCl solution and repeat rinses from step 7. |

| 14. Inject 3 cc of DNase solution through the same hole in the trachea and 3 cc into the right ventricle. Incubate for 1 h at room temperature. |

| 15. Remove lungs from DNase solution and repeat rinses from step 7. |

| 16. Repeat rinses from step 7 using PBS instead of DI solution. |

| 17. Place 1 mm outer diameter (OD) cannula and 3-inch lengths of suture in 50% bleach overnight. |

| 18. Rinse cannula with PBS, punch cannula through the filter in the cap of a culture flask, and superglue in place. |

| 19. Slide trachea over the cannula and tie in place with bleached suture. |

| 20. Fill flask with enough medium to cover the lungs when standing vertically. |

| 21. Infuse cells through the cannula (i.e., through the trachea). |

| 22. Put lung bioreactor system in incubator. Attach 0.2-μm filter to the cannula and hook up to ventilator. |

Solutions: DI solution, sterile filtered deionized (DI) water with 5 × pen/strep; Triton, sterile filtered 0.1% Triton X-100 with 5× pen/strep; deoxycholate, sterile filtered 2% sodium deoxycholate with 1× pen/strep; NaCl, sterile filtered 1 M NaCl with 5 × pen/strep; DNase, sterile filtered 30 μg/mL porcine pancreatic DNase in 1.3 mM MgSO4 and 2 mM CaCl2 with 5 × pen/strep; PBS, sterile phosphate-buffered saline without (w/o) Ca or Mg.

Fetal cell preparation

After cervical dislocation of dams, lungs were removed from E17 fetal mice. The fetal lung cells were isolated by immersion in 1 mL dispase (50 caseinolytic units) for 40 min at room temperature. The digested lungs were then mashed through a screen and filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer. Two million cells were then suspended in 0.5 mL small airway growth medium (SAGM) and injected through the cannula (i.e., via the trachea) into the decellularized lung matrix.

Quantification of ECM components

As a measure of collagen, hydroxyproline (OH-proline) content in decellularized and nondecellularized lungs was measured quantitatively by oxidation of 4-OH-L-proline to pyrrole and reaction with p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde (absorbance read at 560 nm). Elastin levels were measured using the Fastin Elastin quantitative dye-binding kit (Biocolor LTD) according to manufacturer's directions. Laminin levels were measured using a mouse laminin ELISA kit (Insight Genomics) on samples homogenized in protease inhibitor (Roche). GAGs were measured using a previously described dimethylmethylene blue assay.26 Total protein was determined by Bradford assay per manufacturer's instructions (Sigma).

Histologic assessment

A mixture of 0.5 mL Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (OCT; Miles):phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (3:1 ratio) was infused via the trachea into the matrices that were then embedded in OCT in aluminum foil cups, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Cryosections (6 μm) were acetone-fixed (5 min at room temperature) and stained for collagen by Mason's Trichrome (Sigma), elastin by Accustain (Sigma), or for other markers by immunofluorescence as described below.

Immunofluorescence

After fixation in acetone, cryosections (6 μm) were immunofluorescently stained with the following antibodies: chicken anti-laminin (Abcam) with Alexa-fluor 488–labeled anti-chicken secondary (Jackson Immunoresearch); for epithelial cells, biotinylated anti-CK18 (Progen) with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled streptavidin (BDPharmingen); for ATII cells, goat-anti-mouse Pro-SPC (Santa Cruz) with Cy3-labeled anti-goat secondary (Jackson Immunoresearch); for macrophages, FITC-labeled anti-CD11b (clone M1/70, BDPharmingen); for hematopoietic cells, biotinylated anti-CD45 (BDPharmingen) with Cy3-labeled streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch); for endothelial cells, rat-anti-mouse CD31 (Chemicon) with Cy-3-labeled donkey-anti-rat Ab (Jackson Immunoresearch); for Clara cells, goat-anti-rodent CC10 (Santa Cruz) with Cy-3-labeled donkey-anti-goat Ab (Jackson Immunoresearch); for ATI cells, rabbit anti-mouse aquaporin-5 (Chemicon) with Alexa-fluor 488–labeled goat-anti-rabbit secondary (Molecular Probes); and for fibroblasts, rabbit anti-mouse vimentin (Abcam) with Alexa-fluor 488–labeled goat-anti-rabbit secondary (Molecular Probes). Sections were analyzed by confocal microscopy using an Olympus BX51 FluoView 500 confocal microscope and FluoView software.

Scanning electron microscopy

Samples were placed in 2% gluteraldehyde and 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 2–4 h, rinsed in buffer, then placed in 1% osmium tetroxide and 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 2 h. Specimens were rinsed in ultrapure water (NANOpure Infinity®; Barnstead/Thermo Fisher Scientific) and dehydrated in an ethanol series. Once the samples were in 100% ethanol, the material was immersed in liquid nitrogen, placed on a brass surface submerged in liquid nitrogen, and fractured into smaller pieces using a wood dowel. The pieces were then returned to 100% ethanol and processed in a critical point dryer (Autosamdri-814; Tousimis). Material was mounted on aluminum stubs, sputter-coated with gold–palladium, and observed in a scanning electron microscope (S3500N; Hitachi High Technologies America) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV.

Lung pressure–volume measurement tests

Pressure/volume (P/V) values were assessed using the Flexivent plethysmograph system, which is typically used for pulmonary function testing in mice (Scireq) and Flexivent software version 5. The Flexivent is calibrated for open and closed tube systems for each pulmonary test performed. The maximum pressure was set at 25 cm H2O for lung P/V analysis. The positive end expiratory pressure remained constant at 2.5 cm H2O.

Polymerase chain reaction for genomic DNA

Normal and decellularized lungs were processed for DNA extraction and purification using Purelink Genomic DNA mini kit (Invitrogen). Polymerase chain reaction for 30 cycles was done with Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) and sense and antisense primers spanning exons and introns of glyceraldehyde 3-phophate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-actin were prepared at the Microchemical Facility of the University of Minnesota. Primer sequences used for GAPDH were Fwd 5′GGGTTCCTATAAATACGGACTGC3′ and Rev 5′CCACAGTACTGCAGAGCCC3′; those used for β-actin were Fwd 5′TGCCCTGAGTGTTTCTTGTG3′ and Rev 5′ATGGCCTCAGGAGTTTTGTC3′. Products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel with TrackIt 1 kb Plus DNA ladder (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance or Student's t-test. Probability (p) values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Decellularized lung matrix maintains architecture

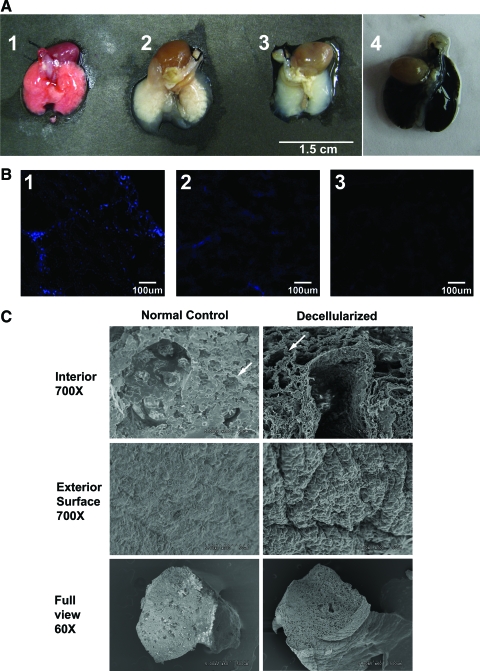

Decellularized matrix represents a natural scaffold on which to rebuild the lung and study the potential of stem cells to regenerate lung tissue. As seen in Figure 1A, decellularized lungs (Fig. 1A, image 3) maintain their overall shape and macroscopic structure. In Figure 1A, image 4 illustrates that infusion with India ink results in complete dispersion through to the distal lung areas, indicating that there would be no blockage or restriction of dispersion of reagents or cells. Infusion of decellularization solutions via both the trachea and the vascular route (through the right ventricle) resulted in more complete decellularization than either route alone as shown by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining of cryosections (Fig. 1B image 3 vs. images 1 and 2). To determine the effect of the decellularization process on lung morphology and architecture, lungs were fixed in glutaraldehyde for scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Figure 1C shows SEM comparing mouse decellularized lungs with nondecellularized normal control lung. The decellularized lung (right panel) appears to be denuded of cells compared to the control lung (left panel). Structures readily visible include a large bifurcating vessel surrounded by alveolar tissue, alveolar septae, collagen fibrils surrounding a vessel, and the characteristic spongy matrix of the lung. As compared to a nondecellularized control lung, this decellularization method appears to maintain the lung architecture and geospatial arrangement of its matrix.

FIG. 1.

Maintenance of lung architecture after whole-lung decellularization. (A) Macroscopic images of lungs at different stages of decellularization process: (1) before decellularization (beginning of day 1), (2) after deoxycholate step (beginning of day 3), showing large amounts of white precipitate (likely cellular breakdown material) within the lungs, and (3) after the final rinses at the end of the process (the end of day 3). Image (4) illustrates that infusion with India ink results in complete dispersion through to the distal lung areas. (B) 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole staining of cryosections of lungs decellularized via (1) the vascular route (through the right ventricle), (2) the trachea, and (3) both the trachea and the vascular route. (C) Scanning electron micrographs are shown comparing mouse decellularized lungs with nondecellularized normal control lung. The top panels (700 × magnification) show a large bifurcating vessel surrounded by alveolar tissue that is acellular in the decellularized lung. The white arrow points to an alveolar septum lined by a capillary (on the top left panel). The top right panel shows a similar area (white arrow) still lined with matrix in the decellularized lung. Collagen fibrils are easy to distinguish surrounding the large vessel. The middle panels (700 × magnification) show the comparison of the exterior surface (the pleural equivalent of the mouse). The lower panels show low power images of the cut lungs (60 × magnification), depicting the maintenance of the characteristic spongy matrix of the lung after decellularization. Images are representative of three sets of lungs prepared for scanning electron micrographs for each condition. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Development of a new decellularized lung matrix bioreactor system

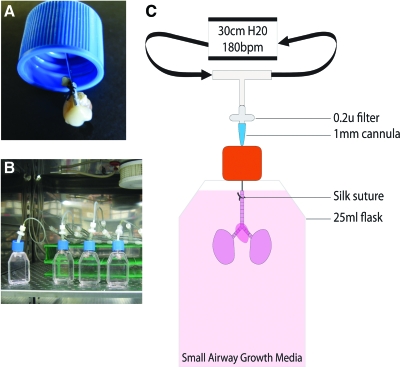

Mechanical stretch, such as that induced by breathing, is also important for lung differentiation as is the ability to provide appropriate nutrients and gas mixtures. Therefore, after decellularization, a small cannula was inserted into the trachea of the matrix and tied in place with silk suture (Fig. 2A). The matrix was then suspended in SAGM (Fig. 2B, C). The cannula was attached to a ventilator to simulate normal, murine breathing-induced stretch (180 breaths/minute; 300 μL volume) and placed in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Videos, available online at www.liebertonline.com). Several matrix bioreactors can be set up simultaneously to the same ventilator (Fig. 2B), enabling evaluation of different bioreactor conditions in the same experiment. The system is highly reproducible with the only limitation being any damage to the trachea that can affect attachment of the cannula and may lead to air leakage.

FIG. 2.

Setup of decellularized lung matrix bioreactor system. (A) Depiction of how the cannula is inserted through the filter cap (cap is 2.5 cm diameter), into the trachea of the decellularized lung and tied in place with silk suture. (B) The matrix is suspended in a flask filled with the small airway growth medium, and the cannula is attached to a ventilator (room air) to simulate normal, murine breathing-induced stretch (180 breaths/min; 300 μL volume) and placed in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. (C) Schematic of bioreactor setup. Supplemental Videos show the bioreactor system in action. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

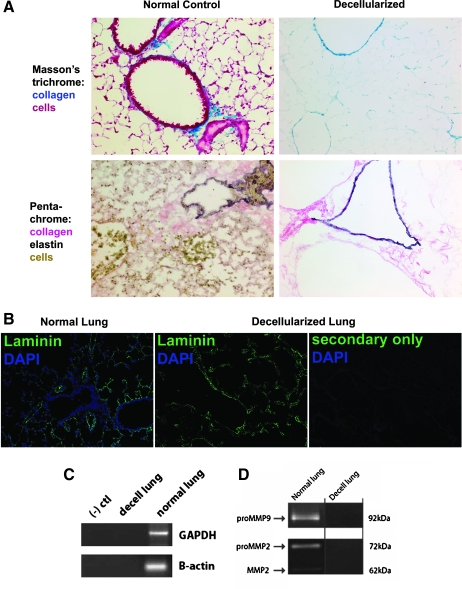

Ventilated decellularized lung matrices maintain geospatial arrangement of ECM components

To assess whether decellularization and subsequent 7-day ventilation of lungs had an adverse effect on ECM components and arrangement, the lungs were frozen in OCT blocks and sectioned for histological analysis. Staining by Masson's trichrome and for elastin (Fig. 3A) demonstrated that the decellularized lungs were indeed acellular and that the pulmonary matrix was intact. Staining for laminin (Fig. 3B), important in alveolar epithelial cell differentiation, showed that the deposition of this matrix component was also relatively unaffected by the decellularization and ventilation in the bioreactor. Further, no cells were seen and no nuclei were evident by DAPI staining, confirming the success of the decellularization process. Polymerase chain reaction for genomic DNA (GAPDH and β-actin) was negative (Fig. 3C), confirming the absence of DNA. Therefore, the geographic placement of the proximal and distal airways, alveoli and vessels, as well as the basement membranes of these structures remained intact even after 7 days of ventilation. Decellularized matrices ventilated for as long as 14 days generated the same results (not shown). The above findings were reproducible even after initially storing decellularized lungs for 7 days at 4°C (infused with PBS) before ventilation in the bioreactor.

FIG. 3.

Maintenance of lung matrix after whole-lung decellularization and ventilation in bioreactor system. (A) Lungs were decellularized and ventilated for 7 days in the lung bioreactor system. Staining by Masson's trichrome (top panels, collagen is blue, 200× magnification) and for elastin (bottom panels, elastin is black, collagen is pink) demonstrates that the decellularized lungs are acellular and the pulmonary matrix is intact. (B) Laminin staining (green, 200 × magnification) shows that laminin deposition is relatively unaffected by the decellularization and ventilation in the bioreactor. DAPI staining of nuclei (blue) is absent in the decellularized lungs. (C) Polymerase chain reaction for genomic DNA (GAPDH and β-actin), using primers spanning introns and exons, was negative in decellularized lung samples. (D) No MMP2 or MMP9 was detected in decellularized lungs by zymography. Images are representative of replicated experiments (n = 3–6 per group). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phophate dehydrogenase.

Homogenates of decellularized lungs were evaluated for matrix metalloprotease (MMP) enzyme activity since any such activity would degrade the decellularized matrices. Figure 3D shows that there was no MMP2 or MMP9 detected by zymography. Assessment of ECM content demonstrated that collagen levels were unaffected by the decellularization process (p = 0.18; Table 2). Although still present to a moderate degree, levels of elastin and laminin were significantly decreased. The decreases seen were due to decellularization and not due to the ventilation in the bioreactor system. Levels of GAGs were also significantly decreased by decellularization but varied widely especially after the 7-day ventilation when the mean level actually increased to normal levels. Since sulfated GAGs are measured with this assay, the decellularization protocol may have affected the sulfate residues.

Table 2.

Extracellular Matrix Components of Decellularized Lungs Pre- and Post-Ventilation for 7 Days in Bioreactor System

| Component | Normal lung | Decellularized lung | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH-Proline (μg) | Pre | 294.4 ± 55.3 | 246.4 ± 60.1 | 1.8 e −1 |

| Post | 292.8 ± 19.2 | 187.1 ± 27.3a | 5.4 e −3 | |

| Elastin (μg) | Pre | 1218.3 ± 103.7 | 767.8 ± 233.6 | 1.5 e −3 |

| Post | 1896.5 ± 299.8 | 659.2 ± 79.6 | 2.3 e −3 | |

| GAGs (μg) | Pre | 257.6 ± 7.8 | 35.0 ± 40.0 | 7.0 e −4 |

| Post | 176.4 ± 35.3 | 181.6 ± 140.1 | 0.9 e −0 | |

| Laminin (ng) | Pre | 1195.2 ± 379.1 | 698.0 ± 280.0 | 1.6 e −7 |

| Post | 1405.3 ± 19.2 | 594.3 ± 244.2 | 5.7 e −4 | |

| Total protein (mg) | Pre | 38.7 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 6.0 e −7 |

| Post | 42.5 ± 2.8 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 1.9 e −7 |

p = 0.16 for decellularized lung pre versus post.

GAGs, glycosaminoglycans.

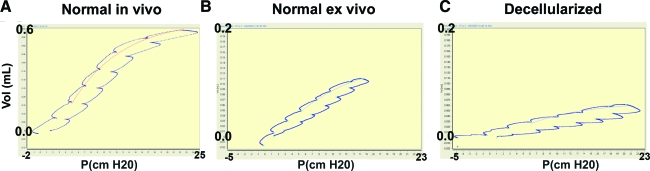

Decellularized lung matrices can be evaluated by P/V measurements

We assessed whether P/V measurements could be done on decellularized lungs as a quantitative real-time measure of the mechanical properties of the lung such as compliance, elasticity, and resistance as is done with pulmonary function testing. If so, then these parameters could be monitored in regard to recellularization with various cell types. P/V values of decellularized B6 mouse lungs were measured with a Flexivent plethysmograph and compared to nondecellularized lungs from age- and sex-matched mice as controls (Fig. 4 and Table 3). As a control, P/V values were measured in vivo in intubated B6 mice and normal B6 lungs taken ex vivo and hooked up to the plethysmograph. The maximum pressure was initially set at 25 cm H2O for P/V flow loop analysis. In nondecellularized lungs taken ex vivo (and suspended in air), higher pressures are reached with lower volumes, compared to in vivo measurements (Fig. 4); that is, the lungs are harder to expand because of atelectasis and the lack of the negative pleural pressure, which normally assists with lung expansion in vivo in the chest cavity. In decellularized lungs, high pressures are reached with even lower volumes, likely due to loss of surfactant, which normally decreases alveolar surface tension, and the loss of cells and matrix components. Further, the P/V curve has shifted even further down and to the right, indicating lower compliance. Table 3 shows measurements of resistance, elastance, and compliance taken before and after 7-day ventilation of nondecellularized and decellularized lungs. Consistent with the decrease in compliance, resistance and elastance are increased in decellularized lungs. Ventilation for 7 days did not significantly change any of the P/V parameters measured in either the nondecellularized lungs or the decellularized lung matrices. Therefore, physiological parameters can be evaluated in decellularized lungs providing the opportunity to measure the effects of infused cells on these parameters. Using a low dose of 1 million fetal lungs cells, which contained 5% pro-SPC+ cells as assessed by fluorescence activated cell scanning (FACS) analysis (cytokeratin 18+ [CK-18+]/pro-SP-C+), was not sufficient to affect P/V parameters after 7 days in the ventilated bioreactor system.

FIG. 4.

Pulmonary function testing (PFT) can be done on decellularized whole-lung matrices. (A) Normal P/V flow loop of the lungs of an orally intubated normal B6 mouse. (B) P/V flow loop of nondecellularized lungs taken ex vivo (and suspended in air). (C) P/V loop of decellularized lungs. All PFTs were measured with a Flexivent plethysmograph set at a maximum pressure setting of 25 cm H2O (y-axis shows volume in mL; x-axis shows pressure in cm H2O). P/V, pressure/volume. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Table 3.

Comparison of Pressure/Volume Parameters Pre and Post 7-Day Ventilation

| Parameter | Ex vivo normal | Decellularizeda | Positive fetal lung cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance | Pre | 1.395 ± 0.065 | 4.844 ± 1.024 | NA |

| (cm H2O · s/mL) | Post | 1.383 ± 0.227 | 5.462 ± 0.617 | 5.753 ± 0.526 |

| Elastance | Pre | 86.81 ± 7.18 | 197.05 ± 27.76 | NA |

| (cm H2O/mL) | Post | 104.72 ± 14.63 | 212.17 ± 29.28 | 221.26 ± 9.41 |

| Compliance | Pre | 0.0116 ± 0.0010 | 0.0052 ± 0.0007 | NA |

| (mL/cm H2O) | Post | 0.0161 ± 0.0046 | 0.0054 ± 0.0005 | 0.0048 ± 0.0045 |

Parameters for normal lungs in vivo: R 0.575 ± 0.025, E 20.53 ± 0.62, C 0.04877 ± 0.00146.

p < 0.05 for all values in the decell group compared to corresponding ex vivo normal value; N = 3/group.

Decellularized lung matrix can support infused fetal ATII cells ex vivo

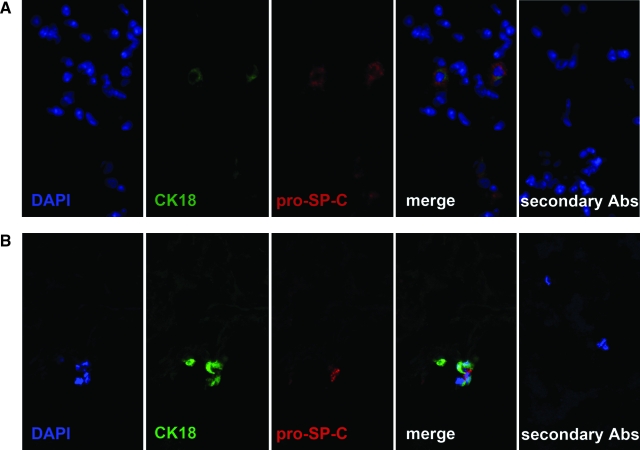

To determine whether early stage lung cells could grow in decellularized lung matrix, 3 million fetal lung cells taken from day E17 gestation B6 mouse lungs were infused as a single-cell suspension in SAGM. After 7 days of ventilation in the lung bioreactor system, cryosections of fetal-cell-injected lung matrices were analyzed for expression of CK 18 (epithelial cells), pro-SP-C (ATII cells), aquaporin-5 (ATI cells), CCSP (Clara cells), CD45 (hematopoietic cells), CD11b (macrophages), CD31 (endothelial cells), and vimentin (fibroblasts). Pro-Sp-C, CK18, and DAPI-positive cells were seen (Fig. 5B) in alveolar areas and appeared to be attached to matrix, consistent with ATII cells whose growth can be supported with SAGM. Co-staining for CK18 is characteristic of ATII cells.27,28 These dual staining cells were seen throughout the distal areas of the lungs. Rarely, CD45-positive cells were seen but did not co-stain with other the markers and appeared to be suspended in airway spaces and not associated with matrix. No cells expressing CD11b, aquaporin-5, CCSP, CD31, or vimentin were not seen at this time point in the medium used (SAGM). Decellularized lung matrices not injected with cells were negative for all markers, including DAPI. These findings were reproducible and observed even on decellularized matrices that had been previously stored for 7 days in PBS, illustrating the potential of using decellularized lungs as a natural 3D, ventilated lung matrix for rebuilding the lung.

FIG. 5.

Decellularized lung matrix bioreactor can support growth of alveolar type II cells. Cryosections of (A) normal and (B) decellularized lung infused with 3 × 106 fetal lung cells and ventilated for 7 days in the bioreactor system were stained with the indicated antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Single-color channels and merged images are shown. Magnification 600 ×. CK 18, cytokeratin 18.

Discussion

The work described in this article is the first to show that decellularized whole lungs can be used as natural scaffolds in a bioreactor system. The results compellingly show that the natural matrix of the lung can be used to identify putative lung progenitor cells and is an ideal scaffold from which to rebuild a lung. Decellularized lung maintained architecture, spatial geometry of structures, and critical ECM components. Further, physiological measurements such as P/V can be performed on decellularized whole-lung matrix.

To date, research on decellularized lung material is scant. Much of the work in the field of decellularized tissue scaffolds is in organs other than lung and involves immersing cut pieces or sheets of organs in detergents and enzyme solutions, osmotic shock, freeze–thawing, or outright physical delamination, followed by lyophilization, sterilization, and rehydration.29,30 With these other methods, the original 3D structure of the complete organ is lost. Nevertheless, those studies demonstrated several important properties of biological scaffolds. Properly prepared decellularized scaffolds maintain the complex composition of their ECM30,31 even for the lung.25 They can be adequately depleted of DNA,32 consistent with our findings, and have adequate oxygen diffusion.33,34 Natural extracellular matrices also have antibacterial activity,35 which may partially explain their resistance to bacterial infection, more so than for synthetic biomaterials, when used for clinical applications.36,37 Degradation products of biological ECM scaffolds have been shown to have tissue-specific chemotactic and mitogenic properties for progenitor cells in vitro38,39 and bone-marrow-derived cells in vivo.40 These properties would be beneficial for continued recellularization of the matrix once incorporated in vivo.

Our study is also the first to demonstrate the mechanical properties of decellularized lungs by pulmonary function tests (PFTs). We found that although similar levels of collagen were present compared to controls, the decellularized lungs had extremely low compliance. Since PFTs on decellularized lungs have not been done previously, the significance in the magnitude of compliance reduction as compared to normal control lungs is unclear. However, since compliance is an indication of collagen content (compliance goes down with increases in collagen), our data are probably a reflection of the increase in collagen content relative to the remaining lung contents (Table 2 shows the decrease in total protein content). That is, collagen now represents a higher percentage of lung tissue. The depletion of surfactant is also a major factor. The decrease in elastin may also contribute to the decreased compliance. The ability to measure functional parameters in decellularized lungs is important because it provides the opportunity to measure the effects of infusing different lung cell populations used for recellularization. A low dose of 1 million fetal lungs cells, which contained 5% pro-SPC+ cells, was not sufficient to affect P/V parameters after 7 days in the ventilated bioreactor system. It is likely that higher doses of cells or longer incubation times may be necessary to effect a change in matrix compliance.

Although lower levels of laminin were found in the decellularized matrices compared quantitatively to controls, immunofluorescence results showed similar distribution. The maintenance of moderate levels of laminin is encouraging as this component is important for alveolar cell differentiation and barrier function.13,17,41–45 Because it is unknown whether the decellularization procedure has affected antigenic epitopes recognized by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, the values obtained may be underestimated. The same is also true for the lower GAG content in the decellularized lungs. The method used to measure GAG levels measures sulfated GAGs and the decellularization protocol may have affected the sulfate residues resulting in the wide distribution of measured values obtained using this assay. The relative importance of GAGs to lung cell differentiation is not known, but GAGs have been reported to be immunostimulatory.46,47 Therefore, the low levels of GAGs found in decellularized lungs may be advantageous for contributing to a relatively immunoprivileged status of the matrices (i.e., not conducive to creating an inflammatory milieu on first exposure of infused cells to the matrix).

To determine whether decellularized lungs were capable of supporting growth of pulmonary cells, we demonstrated that infused fetal lung cells could be maintained in the lung bioreactor system and that CK18+/pro-SPC+ cells could be readily seen in the alveolar areas, consistent with the location of ATII cells. Several cells were seen at the corners of alveolar septae, that is, the typical location of ATII cells, consistent with the preferential growth of ATII cells in SAGM.

We postulate that the decellularized lung bioreactor system may be used in other ways. It may be the ideal setting for preparing putative therapeutic cells for in vivo use. In this system, cells would be trained in a natural lung matrix environment that encompasses geospatial patterning as well as mechanical stretch. Further, the ability to study cellular interactions in a ventilated, natural matrix may have a major impact on our understanding of how an injured lung can be effectively repaired. Our lung bioreactor system may provide a bioengineering tool for the study of lung regeneration from pulmonary stem cells. By comparing putative lung progenitors head-to-head and in combination, substantial progress can be made in optimizing bioengineering of the lung. Advances in decellularized tissue bioreactors may lead to the use of bioengineered lung tissue for severe lung diseases as it provides a form of cell therapy in the context of lung structure, composition, and physiology. Projecting into the future of this field, the ability to bioengineer lungs using autologous cell sources (e.g., bone marrow) on a decellularized matrix from any donor, even of cadaver origin, will circumvent transplant rejection issues and dramatically change the lung transplant arena.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The expert technical assistance of Kevin Tram and Tyler Metz is greatly appreciated. We appreciate the SEM work performed by the College of Biological Sciences' Imaging Center at the University of Minnesota. This work was funded by NIH R01 HL055209 awarded to B.R.B. and A.P.M.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Weiss D.J., et al. Stem cells and cell therapies in lung biology and lung diseases. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:637. doi: 10.1513/pats.200804-037DW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macchiarini P., et al. First human transplantation of a bioengineered airway tissue. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:638. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreider M. Kotloff R.M. Selection of candidates for lung transplantation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:20. doi: 10.1513/pats.200808-097GO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trulock E.P., et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-first official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report—2004. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:804. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estenne M. Hertz M.I. Bronchiolitis obliterans after human lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:440. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200201-003pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lama V.N. Update in lung transplantation 2008. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:759. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200902-0177UP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orens J.B. Garrity E.R., Jr. General overview of lung transplantation and review of organ allocation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:13. doi: 10.1513/pats.200807-072GO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trulock E.P. Lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:789. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arcasoy S.M. Kotloff R.M. Lung transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1081. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904083401406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone K.C., et al. Allometric relationships of cell numbers and size in the mammalian lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:235. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franks T.J., et al. Resident cellular components of the human lung: current knowledge and goals for research on cell phenotyping and function. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:763. doi: 10.1513/pats.200803-025HR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone K.C., et al. Distribution of lung cell numbers and volumes between alveolar and nonalveolar tissue. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:454. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuger L., et al. Laminin and heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediate epithelial cell polarization in organotypic cultures of embryonic lung cells: evidence implicating involvement of the inner globular region of laminin beta 1 chain and the heparan sulfate groups of heparan sulfate proteoglycan. Dev Biol. 1996;179:264. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adamson I.Y. Relationship of mesenchymal changes to alveolar epithelial cell differentiation in fetal rat lung. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1992;185:275. doi: 10.1007/BF00211826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shigemura N., et al. Lung tissue engineering technique with adipose stromal cells improves surgical outcome for pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1199. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-406OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortiella J., et al. Tissue-engineered lung: an in vivo and in vitro comparison of polyglycolic acid and pluronic F-127 hydrogel/somatic lung progenitor cell constructs to support tissue growth. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1213. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondrinos M.J., et al. Engineering three-dimensional pulmonary tissue constructs. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:717. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugihara H., et al. Reconstruction of alveolus-like structure from alveolar type II epithelial cells in three-dimensional collagen gel matrix culture. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:783. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondrinos M.J., et al. A tissue-engineered model of fetal distal lung tissue. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L639. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00403.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen P., et al. Formation of lung alveolar-like structures in collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffolds in vitro. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1436. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mondrinos M.J., et al. In vivo pulmonary tissue engineering: contribution of donor-derived endothelial cells to construct vascularization. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:361. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrade C.F., et al. Cell-based tissue engineering for lung regeneration. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L510. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00175.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavik E. Langer R. Tissue engineering: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;65:1. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1580-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ott H.C., et al. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lwebuga-Mukasa J.S. Ingbar D.H. Madri J.A. Repopulation of a human alveolar matrix by adult rat type II pneumocytes in vitro. A novel system for type II pneumocyte culture. Exp Cell Res. 1986;162:423. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbosa I., et al. Improved and simple micro assay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans quantification in biological extracts and its use in skin and muscle tissue studies. Glycobiology. 2003;13:647. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasper M., et al. Heterogeneity in the immunolocalization of cytokeratin-specific monoclonal antibodies in the rat lung: evaluation of three different alveolar epithelial cell types. Histochemistry. 1993;100:65. doi: 10.1007/BF00268879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlichenmaier H., et al. Expression of cytokeratin 18 during pre- and post-natal porcine lung development. Anat Histol Embryol. 2002;31:273. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0264.2002.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert T.W. Sellaro T.L. Badylak S.F. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3675. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badylak S.F. Freytes D.O. Gilbert T.W. Extracellular matrix as a biological scaffold material: structure and function. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:1. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown B., et al. The basement membrane component of biologic scaffolds derived from extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:519. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert T.W. Freundb S.J. Badylak S.F. Quantification of DNA in biologic scaffold materials. J Surg Res. 2009;152:135. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Androjna C., et al. Oxygen diffusion through natural extracellular matrices: implications for estimating “critical thickness” values in tendon tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:559. doi: 10.1089/tea.2006.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valentin J.E., et al. Oxygen diffusivity of biologic and synthetic scaffold materials for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;91:1010. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brennan E.P., et al. Antibacterial activity within degradation products of biological scaffolds composed of extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2949. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shell D.H.t, et al. Comparison of small-intestinal submucosa, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene as a vascular conduit in the presence of gram-positive contamination. Ann Surg. 2005;241:995. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000165186.79097.6c. discussion 1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carlson G.A., et al. Bacteriostatic properties of biomatrices against common orthopaedic pathogens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321:472. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brennan E.P., et al. Chemoattractant activity of degradation products of fetal and adult skin extracellular matrix for keratinocyte progenitor cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2:1. doi: 10.1002/term.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reing J.E., et al. Degradation products of extracellular matrix affect cell migration and proliferation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:605. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zantop T., et al. Extracellular matrix scaffolds are repopulated by bone marrow-derived cells in a mouse model of achilles tendon reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1299. doi: 10.1002/jor.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koval M., et al. Extracellular matrix influences alveolar epithelial claudin expression and barrier function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:172. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0270OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demaio L., et al. Characterization of mouse alveolar epithelial cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L1051. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00021.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin Y.M. Zhang A. Rippon H.J. Bismarck A. Bishop A. Tissue engineering of lung: the effect of extracellular matrix on the differentiation of embryonic stem cells to pneumocytes. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1515. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olsen C.O., et al. Extracellular matrix-driven alveolar epithelial cell differentiation in vitro. Exp Lung Res. 2005;31:461. doi: 10.1080/01902140590918830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen N.M., et al. Epithelial laminin alpha5 is necessary for distal epithelial cell maturation, VEGF production, and alveolization in the developing murine lung. Dev Biol. 2005;282:111. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wrenshall L.E., et al. Modulation of macrophage and B cell function by glycosaminoglycans. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:391. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Termeer C., et al. Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan activate dendritic cells via toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 2002;195:99. doi: 10.1084/jem.20001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.