Abstract

A number of studies suggest that people who have strong social support systems at church tend to enjoy better mental and physical health. Yet little is known about the factors that promote strong church-based social support networks. The purpose of this study is to show that key religious beliefs may have something to do with it. A new construct – spiritual connectedness – is introduced for this purpose. Spiritual connectedness refers to an awareness of the bond that exists among all people and the sense of the interdependence among them. Data from a nationwide longitudinal survey of older people in the United States reveal that a strong sense of spiritual connectedness is associated with providing more emotional support and tangible assistance to fellow church members over time. The data further reveal that older people with a strong sense of spiritual connectedness are more likely to pray for others, as well.

A number of researchers maintain that people who are deeply involved in religion tend to have more well-developed and more efficacious social relationships than individuals who are less involved in religion (e.g., Ellison & Levin, 1998). In the process of coming to this conclusion, researchers have typically taken one of three approaches to assess the potentially unique influence of religion on social ties. First, some investigators have examined the interface between involvement in religion (typically the frequency of church attendance) and global measures of social support that combine assistance that has been provided by people inside as well as outside of church (e.g., Dulin 2005; Ellison, Boardman, Williams, & Jackson, 2001; Ellison & George, 1994; Mattis et al., 2001). Other researchers have focused on social support that is provided specifically by fellow church members (e.g., Fiala, Bjorck, & Gorsuch, 2002; Maton, 1987; Taylor, Lincoln, & Chatters, 2005). A third strategy was taken in a recent study by Krause (2006a). He compared the effects of social support provided by coreligionists with support from members of secular social networks. Regardless of the strategy that has been used, the findings from these studies tend to converge on the same conclusion: Greater involvement in religion appears to be associated with more social support and more effective social network functioning.

The reasons for the beneficial influence of religion on social relationships are both plausible and straightforward. The norms and values that are embedded in official church doctrine extol the virtues of being compassionate (Wuthnow 1991), helping those who are in need (Krause, 2007), and forgiving people who have done something wrong (Rye et al., 2000). The influence of these shared norms and values is furthered bolstered by the fact that congregations tend to be relatively homogeneous with respect to race and socioeconomic status. And, as McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook (2001) argue, this demographic similarity breeds solidarity.

Even though the association between religious precepts and social relationships is widely discussed, it has rarely been evaluated empirically. The purpose of the current study is to address this gap in the knowledge base by assessing the interface between core religious beliefs and social relationships in the church. Doing so is important for the following reason. A substantial effort has been exerted to devise interventions to enhance physical and mental health by improving secular social relationships (see Hogan, Linden, & Najarian, 2002, for a review of this research). More recently, there has been growing interest in developing support-based interventions within the church, as well (Kidorf et al., 2005; Peterson, Yates, Atwood & Hertzog, 2005). Arriving at a deeper understanding of the factors that promote better social relationships should provide valuable insight into how to design more effective social support interventions in the church.

The discussion that follows is divided into three main sections. The theoretical underpinnings of this study are developed in the first section. Then, the sample, study model, and survey measures are presented in section two. Following this, the findings are reviewed and discussed in the third section.

Exploring the Religious Foundation of Social Relationships

Three issues were addressed in the process of developing the theoretical framework for this study. The first issue involves identifying the core beliefs that form the religious foundation of church-based social ties. A new construct B spiritual connectedness B is introduced to illuminate the fundamental nature of this relationship. The second issue has to do with the sample that is evaluated in the current study. The data for this study come from a nationwide, longitudinal survey of older adults. Consequently, the importance of studying the religious basis of social relationships in late life is explored. An extensive body of research suggests that older African Americans tend to have more well-developed social relationships in church than older Whites (Krause, 2002a; Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2004). Therefore, the third issue involves evaluating the potentially important influence of race on core religious beliefs that shape social relationships with others and social ties in the church.

Spiritual Connectedness and Church-Based Social Ties

Davidson (1972) conducted one of the first studies to examine religious beliefs about relationships with others. In this work, he made a distinction between the vertical and horizontal dimensions of religion. The vertical dimension refers to the relationship that a person establishes with God, whereas the horizontal dimension refers to relationships that an individual develops with other people. Davidson (1972) devised a measure of the horizontal dimension that consists of two indicators. The first item deals with the need to love one’s neighbors and the second involves the importance of helping one’s fellow man. Although loving and helping others clearly affects the quality of the social relationships that people develop, a deeper and more fundamental set of beliefs may lie behind them. More specifically, it may not be enough to believe that people should love and help each other B instead, these beliefs are likely to have a greater effect on the development of social ties if people to have a clear sense of why loving and helping others is important. A core premise in the current study is that beliefs about loving and helping others rest on a fundamental sense of spiritual connectedness. Spiritual connectedness is defined as the belief that there is a close bond among all people, regardless of whether they are religious or not. It is a sense of oneness that arises from the individual’s awareness of his or her unity with the wider social whole. When people realize that their fate is tied to the fate of all others, their attitude shifts from one of hostility, competition, or indifference to one of empathy, compassion, and concern. It is out of this wider, more enduring sense of oneness and connectedness that the unique aspects of religiously-based social relationships are likely to arise.

The notion that all human life is interconnected has a long history that goes back to the fundamental teachings of the great religious prophets. For example, in a widely cited passage in the gospel of Matthew, Jesus talks about how people should relate to others, including strangers and the poor. The sense of brotherhood and connectedness with others is especially evident when Jesus points out that, “Inasmuch as you have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, you have done it unto me” (KJV, Matthew 26:40). Since then, a number of classic social theorists have discussed how social relationships among the faithful are based on an underlying religiously-motivated sense of connectedness. Among them are Edward Alsworth Ross, Charles Horton Cooley, and Georg Simmel. Ross, who was one of the first presidents of the American Sociological Association, wrote an insightful paper on religion in 1896. In this work, he captured the essence and importance of spiritual connectedness when he observed that, “It is one thing to recognize the manifold interactions of men in social life and to act accordingly; it is quite another thing to believe that apart from, and prior to, the bonds of interdependence, trust, or affection that grow up in the social mechanism, there is a unity of essence that calls for justice and sympathy between men. The mere perception of likeness fosters sympathy, but the conviction of underlying oneness does more. It destroys the egocentric world which each unreflecting creature builds for itself … It fosters respect for others … It lessens our willingness to use them as means to our own ends” (Ross 1896, p.441, emphasis added).

Similar views were espoused by Cooley (1927), who is widely regarded as one of the founders of social psychology. In the last book he wrote, Cooley (1927, p. 241) emphasized the importance of seeing the fundamental connectedness and interdependence among all people: “The actual interdependence of human life, of persons, classes, nations, far surpasses our awareness of it, and still more our arrangements for cooperation. Wisdom is largely the perception of this interdependence, and the endeavor to give it organs.” Cooley (1927) went on to link this sense of connectedness and interdependence directly with religion: “The best religious education would be one that accustomed us from childhood to cooperation … in service of human wholes. Through the family, the play-group, the school, the community, the nation, humanity, we might acquire an enlarging sense of God” (Cooley, 1927, p. 265).

Simmel (1898/1997) also discussed how the concept of unity lies at the core of religious life. The notion of spiritual connectedness is especially evident in the following passage that was taken from his work: “…what does unity signify, but that many are mutually related, and that the fate of each is felt by all?” (Simmel, 1898/1997, p.111).

The goal of the research that follows is to contribute to the literature on social relationships in the church by seeing whether spiritual connectedness is associated with several different types of church-based social support in late life.

Assessing Spiritual Connectedness and Social Relationships in Late Life

As reported above, the data for the analyses that are presented below come from a longitudinal, nationwide survey of older people. Although the sample is composed solely of individuals who are in late life, it is nevertheless helpful to briefly reflect on why it is important to study the relationship between spiritual connectedness and church-based social ties among people in this age group.

A number of theorists maintain that social relationships become more important as people enter and go through old age. For example, Carstensen’s (1992) theory of socioemotional selectivity specifies that as people get toward the end of life, they place a greater emphasis on social relationships that are emotionally close. Similarly, Tornstam’s (2005) theory of gerontranscendence holds that individuals tend to become more altruistic, and less materialistic, with advancing age. Kohlberg (1973) is widely known for his theory of moral development. This theory initially consisted of six developmental stages. But during the end of his career, he added a seventh stage that emerges in late life. Kohlberg (1973, p. 501) argued that during the seventh stage of moral development, the emphasis on one’s own self begins to subside and, “We sense the unity of the whole and ourselves as part of that unity.” Perhaps, the clearest link between ageing and a sense of spiritual connectedness is found in the work of Levenson, Jennings, Aldwin, and Shiraishi (2005). Their research focuses on the notion of self-transcendence. According to this perspective, as people get older they make an effort to become more tolerant of others, more compassionate, and they place less emphasis on material things. Moreover, as the following survey measures of self-transcendence reveal, a sense of connectedness with the larger social whole is an intimate part of this construct, as well: “I feel much more compassionate, even toward my enemies,” “I feel that my individual life is part of a greater whole,” and “I feel a greater sense of belonging with both earlier and future generations” (Levenson et al., 2005, p. 136). If people tend to feel closer to others as they grow older, and if they become more attuned to their place in the larger social order, then the relationship between spiritual connectedness and church-based social support should be especially evident in samples comprising elderly people.

Research also indicates that people who are presently older are more deeply involved in religion than individuals who are currently younger. More specifically, a number of studies suggest that compared to younger adults, older people tend to go to church more often, pray more frequently, read the Bible more often, and are more likely to report that religion plays a very important role in their lives (e.g., Barna, 2002; Gallup & Lindsay, 1999). If religion promotes a sense of spiritual connectedness and older people are more religious than younger individuals, then it, once again, makes sense to study the relationship between spiritual connectedness and church-based social support in samples that consist of older adults.

Examining Variations by Race

There are both historical and cultural reasons why a sense of spiritual connectedness and social relationships may be especially important in the African American community. The historical influences were discussed some time ago by Nelsen and Nelsen (1975). As these investigators argue, the church has been the center of the African American community since its inception. Due to centuries of prejudice and discrimination, Black people have turned to the church for spiritual, social, and material sustenance because it was the only institution in their community that was built, funded, and wholly owned by members of their own race. As a result, the church became a conduit for the delivery of social services. Moreover, the first schools for Black children were located in them. In fact, it is not surprising to find that many of the great political leaders in the Black community have strong ties to the church, and many have been members of the clergy (e.g., Martin Luther King, Jr.). Since researchers have known for some time that conflict with out-groups tends to promote greater in-group cohesiveness and solidarity (Tajfel, 1982), the historical experiences of Black people are likely to have fostered an especially pronounced feeling of connectedness with others.

Evidence that a strong sense of spiritual connectedness may be associated with well-developed social relationships in the Black church is found in the work of Mattis and Jagers (2001). Sounding much like Davidson (1972), Mattis and Jagers (2001, p. 523) conclude that, “…African American religiosity and worship traditions emphasize both a profound sense of intimacy with the divine, and a horizontal extension of that intimacy into the human community.” But the deep sense of connectedness in the Black church is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the work of the noted Black theologian, J. Deotis Roberts (2003). He argues that, “The black church, as a social and religious body, has served as a kind of ‘extended family’ for blacks. In a real sense then, thousands of blacks who have never known real family life have discovered the meaning in real kinship in the black church” (Roberts, 2003, p. 78).

In addition to arising from historical forces, the strong social ties that flourish in Black churches are influenced by wider cultural factors, as well. Themes involving a sense of connectedness with others are especially evident. Baldwin and Hopkins (1990) went to great lengths to identify the key elements of the African American world view or culture. They argue persuasively that African American culture is characterized by an emphasis on harmony, cooperation, collective responsibility, “groupness,” and “sameness.” Similar insights emerge in the work of Maynard-Reid (2000, p. 61), who maintained that, “The communal world view is most evident in the extended family. African cultural tradition sees every woman, for example, as mother, aunt, grandmother, sister, and daughter. All are family. Africans and African-Americans view life as one-in-community … This cultural world view of necessity is carried over into worship. Worship therefore is a community happening in which kinship and mutual interdependence are affirmed.” Because institutions reflect the elements of the wider culture in which they are embedded, it follows that these key cultural characteristics should permeate the Black church. And because the key elements of Black culture that are identified by Maynard-Reid (2000), as well as Baldwin and Hopkins (1990), deal directly with interpersonal relationships, one would expect to find that, compared to older Whites, older Blacks are more likely to feel a deeper sense of spiritual connectedness with others and older Blacks should exchange more support with the people in their congregations. As noted earlier, research consistently shows that older Blacks both give and receive more social support in church than older Whites (e.g., Krause, 2002a). However, there do not appear to be any studies that have been designed to see whether there are also race differences in the underlying belief structure that supports these interpersonal ties. It is for this reason that assessing race differences in spiritual connectedness is a major focal point in the analyses that follow.

Method

Sample

The data for this study come from a nationwide, longitudinal survey of older Whites and older African Americans. The study population was defined at the baseline survey as all household residents who were either Black or White, noninstitutionalized, English-speaking, and at least 66 years of age. Geographically, the study population was restricted to eligible persons residing in the coterminous United States (i.e., residents of Alaskan and Hawaii were excluded). Finally, the study population was restricted to currently practicing Christians, individuals who were Christian in the past but no longer practice any religion, and people who were not affiliated with any faith at any point in their lifetime. This study was designed to explore a range of issues involving religion. As a result, individuals who practice a religion other than Christianity were excluded because the members of the research team felt it would be too difficult to devise a comprehensive battery of religion measures that would be suitable for individuals of all faiths.

The sampling frame for this study consisted of all eligible persons contained in the beneficiary list maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). A five-step process was used to draw the sample from the CMS files. A detailed discussion of this sampling strategy is provided by Krause (2002b).

Interviewing for the baseline survey took place in 2001. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The data collection was performed by Harris Interactive (New York). A total of 1,500 interviews were completed. Elderly Blacks were oversampled so that sufficient statistical power would be available to assess race differences in religion. As a result, the Wave 1 sample consisted of 748 older Whites and 752 older African Americans. The overall response rate for the Wave 1 interviews was 62%.

The Wave 2 survey was completed in 2004. Once again, the interviews were conducted by Harris Interactive. A total of 1,024 of the original 1,500 study participants were re-interviewed successfully, 75 refused to participate, 112 could not be located, 70 were too ill to participate, 11 had moved to a nursing home, and 208 were deceased. Not counting those who had died or were placed in a nursing home, the re-interview rate for the Wave 2 survey was 80%.

As discussed below, three different outcome variables are examined in this study. After using listwise deletion to deal with the item nonresponse, the number of cases in these analyses range from 554 to 854. Based on the group consisting of 854 older adults, preliminary analysis reveals that the average age of the participants at the baseline interview was 74.1 years (SD = 6.0 years), approximately 38% were older men, and 52% were White. The data further indicate that the respondents in this study reported they had successfully completed 11.7 years of schooling (SD = 3.4 years). These descriptive analyses, as well as the substantive findings that follow, are based on data that have been weighted.

Study Model

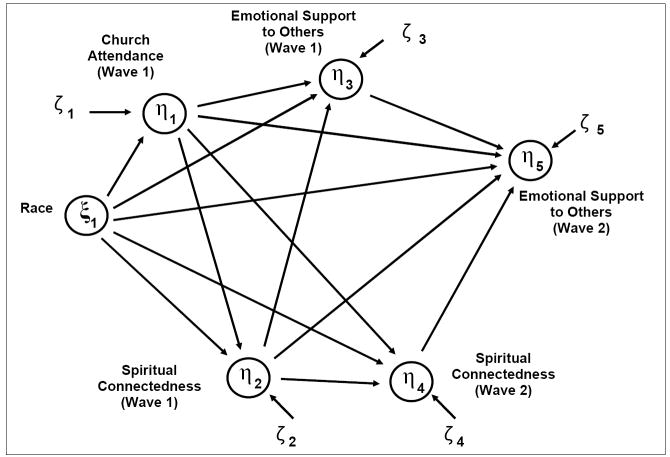

The latent variable model that was designed to assess the relationship between spiritual connectedness and church-based social support is presented in Figure 1. It should be emphasized that the relationships among the constructs depicted in Figure 1 were evaluated after the effects of age, sex, and education were controlled statistically. Moreover, in order to make the model easier to read, the elements of the measurement model (i.e., the factor loadings and measurement error terms) are not depicted in Figure 1. Before turning to a discussion of how the constructs in this model were measured, it is important to discuss two key features of this conceptual scheme.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of spiritual connectedness and church-based emotional support

First, the model depicted in Figure 1 was estimated three times. The first time, emotional support by older people to their fellow church members served as the outcome. Then, tangible help given to fellow parishioners and praying for other people were used in second and third estimations, respectively. As these outcomes reveal, an emphasis is placed in the current study on giving assistance rather than receiving it. This was done for the following reason. If church-based social relationships arise from feeling connected with other people, then the link between these constructs is more likely to be found with measures of giving support because the decision to help others is more likely to be influenced by these core religious beliefs. In contrast, an older person may accept help from others simply because he or she needs it and not because they feel a particularly strong sense of spiritual connectedness with the individual who provided it.

The second feature of the model depicted in Figure 1 has to do with the way it is specified. Because the data that are used in this study are longitudinal, the goal is to predict change in support provided to others (e.g., Wave 2 emotional support provided to others controlling for Wave 1 emotional support provided to others). By also including the Wave 1 and the Wave 2 measures of spiritual connectedness in the model, it is possible to assess the influence of change in spiritual support on change in emotional support provided to others (for a more detailed discussion of this type of model specification see Finkel, 1995, and Menard, 1991). This specification conveys a more dynamic sense of the relationship between spiritual connectedness and providing emotional support to others. In addition, including the Wave 2 as well as the Wave 1 measures of spiritual connectedness in the study model makes it possible to more accurately assess the causal lag. The causal lag represents the time it takes for the independent variable to produce change in the outcome. As discussed above, the between-round interval in the current study is three years. If older people have a strong sense of connectedness with others, then it is not clear why it would take three full years for them to act on these beliefs by helping their fellow church members. Instead, it seems more likely that these religious beliefs will promote helping behaviors much more quickly. By including both the Wave 1 and Wave 2 measures of spiritual connectedness in the model, it is possible to evaluate this possibility directly.

Measures

Table 1 contains the survey items that were used to measure the core constructs in the analyses presented below. The procedures that were used to code these indicators are provided in the footnotes of this table.

Table 1.

Core study measures

|

These items are scored in the following manner (coding in parentheses): Strongly disagree (1); disagree (2); agree (3); strongly disagree (4).

These items are scored in the following manner: Never (1); once in a while (2); fairly often (3); very often (4).

This item is scored in the following manner: Respondent never prays (1); respondent prays, but never for other people (2); less than once a month (3); once a month (4); a few times a month (5); once a week (6); a few times a week (7); once a day (8); several times a day (9).

This item is scored in the following manner: Never (1); less than once a year (2); about once or twice a year (3); several times a year (4); about once a month (5); 2-3 times a month (6); nearly every week (7); every week (8); several times a week (9).

Spiritual Connectedness

As shown in Table 1, three items were used to measure spiritual connectedness. These indicators ask, for example, if older study participants believe that their faith helps them see a common bond among all people. These indicators were developed as part of an extensive program of qualitative research that was designed to derive better measures of religion for use with older people (Krause, 2002c). These items were written so that they refer to a sense of connectedness that arises specifically from one’s own faith. Writing the indicators in this manner grounds them in an explicitly religious context. This is important because a sense of connectedness with others may arise from a number of sources outside religion. In fact, people who are openly antireligious may, nevertheless, feel a sense of connectedness with other individuals. Evidence of this may be found, for example, by turning to the work of the well-known philosopher, Bertrand Russell. In 1957, he wrote an essay that was titled, “Why I am Not a Christian” (1957/2000). In it, Russell argued that God is just a figment of man’s superstitious nature and that there is a good deal of senseless suffering in life. Even so, he saw a deep underlying connectedness among all people: “… let us remember that they are fellow sufferers in the same darkness, actors in the same tragedy as ourselves” (Russell, 1957/2000, p. 76-77). And because of this, Russell (1957/200, p. 76) maintained that, “Be it ours to shed sunshine on their path, to lighten their sorrows by the balm of our sympathy, to give them the pure joy of never-tiring affection …”

The items in Table 1 are coded so that a high score denotes a greater sense of spiritual connectedness with others. The mean value of this brief composite at Wave 1 is 10.53 (SD = 1.69) and the mean at Wave 2 is 10.49 (SD = 1.80).

Emotional Support Provided to Others

Three items were also included in the survey to assess how often older study participants provide emotional support to their fellow church members. These measures were also developed by Krause (2002c). A word is in order about the way the emotional support items were administered. It did not make sense to ask older people questions about providing social support to fellow church members if they either never go to church or attend worship services only rarely. Consequently, the items that assess providing emotional support to coreligionists were not administered during the Wave 1 survey to 374 older people who went to church no more than twice a year. The same strategy was implemented in the Wave 2 survey, as well.

A high score on the emotional support indicators means that the older people in this study provide emotional assistance to their coreligionists more often. The mean at Wave 1 is 9.04 (SD = 2.35) and the mean at Wave 2 is 8.98 (SD = 2.39).

Tangible Support Provided to Others

Four items that were devised by Krause (2002c) were used to measure how often older people give tangible help to the individuals they worship with. Like the emotional support items, the indicators that assess the provision of tangible support to others were administered only to those older people who attend church services more than twice a year. A high score on these items stands for more frequent tangible assistance. The mean tangible support score at Wave 1 is 6.89 (SD = 2.71) and the mean at Wave 2 is 6.83 (SD = 3.16).

Praying for Others

As research by Krause (2003) reveals, one way in which older people help others is to pray for them. Because older people who pray for others are actively doing something on behalf of someone who is in need, praying for others may be construed as a type of social support. As shown in Table 1, the older people in this study were asked how often they pray when they are alone for the people they know. Unlike the measures of emotional and tangible support, this item was administered to study participants regardless of how often they go to church. Moreover, the question was not focused on praying solely for fellow church members. Consequently, including prayers for others in the study serves to broaden the scope of inquiry by seeing whether spiritual connectedness is associated with helping a potentially wider circle of people who may or may not be involved in religion.

This item was coded so that a high score represents older people who pray for others more frequently. The mean at Wave 1 is 7.38 (SD = 2.16) and the mean at Wave 2 is 7.59 (SD = 1.98).

Frequency of Church Attendance

The older people in this study were asked how often they attend religious services. This measure was included in the study models in order to trace how a sense of spiritual connectedness arises. More specifically, the sermons, prayers, and hymns that are part of formal worship services frequently contain basic religious teachings that are designed to promote compassion, helping others, and forgiveness. Exposure to these precepts during worship services should help ensure that they are adopted by older people. But more than merely listening to basic religious teachings may be at work here. These religious precepts are also more likely to be internalized if an older person shares these learning experiences with others and sees that their fellow church members subscribe to them. As Stark and Finke (2000, p. 107) point out, “An individual’s confidence in religious explanations is strengthened to the extent that others express their confidence in them.”

The item that assesses the frequency of church attendance is coded so that a high score identifies older people who go to church more often. Only the Wave 1 measure of church attendance is included in the analyses that follow. The mean is 6.15 (SD = 2.57).

Race

Race is measured with a single binary indicator that contrasts older Whites (scored 1) with older African Americans (scored 0).

Demographic Control Variables

As noted earlier, the relationships among the constructs in Figure 1 were assessed after the effects of age, sex, and education were controlled statistically. Age and education are coded continuously in years whereas sex is assessed with a binary variable (1 = men; 0 = women).

Results

Assessing the Effects of Sample Attrition

As the discussion of the sampling procedures for this study reveals, some older people who were interviewed for the baseline survey did not participate in the follow-up interview. The loss of subjects over time may bias study findings if it occurs in a non-random manner. The first set of analyses that were performed in this study was designed to evaluate the extent of this potential problem. Although it is difficult to determine if the loss of subjects has biased study findings, some preliminary insight can be obtained by seeing if select data from the Wave 1 survey is associated with study participation status at Wave 2. Evidence of potential bias would be found if any statistically significant relationships emerge from this analysis. The following procedures were used to implement this strategy. First, a nominal-level variable consisting of three categories was created to represent older adults who remained in the study (scored 1), older people who were alive but did not participate at Wave 2 (e.g., those who refused to participate; scored 2), and older adults who died during the follow-up period (scored 3). Then, using multinomial logistic regression, this categorical measure was regressed on the following Wave 1 measures: Age, sex, education, race, church attendance, providing emotional support to fellow church members, providing tangible help to coreligionists, praying for others, and spiritual connectedness. The category representing older people who remained in the study served as the reference group in this analysis.

The data from the attrition analyses (not shown here) reveal that compared to older people who remained in the study, older adults who dropped out provided less tangible support to their fellow church members at the baseline survey (b = !.170; p < .001, odds ratio = .844). Moreover, the findings suggest that compared to those who remained in the study, people who died were more likely to be older (b = .070; p < .001; odds ratio = 1.073), less likely to attend church often (b = !.188; p < .01; odds ratio = .829), and less likely to provide tangible support to fellow church members (b = !.124; p < .05; odds ratio = .883). Older people who died during the follow-up period also had fewer years of schooling (b = !.075; p < .05; odds ratio = .928) than older adults who remained in the study.

Taken together, the findings from the analysis of sample attrition suggest that the loss of subjects over time did not occur in a random manner. However, there is considerable debate in the literature about whether study findings are biased if sample attrition occurs non-randomly (see Groves et al., 2004, for a detailed discussion of this controversy). Because this complex issue cannot be resolved in the current study, it is best to keep the influence of non-random sample attrition in mind as the results provided below are reviewed.

Substantive Findings

The latent variable models that were assessed in this study were evaluated with the maximum likelihood estimator in Version 8.71 of the LISREL statistical software program (du Toit & du Toit, 2001). Use of this estimator rests on the assumption that the observed indicators in a model are distributed normally. However, preliminary tests of the study measures (not shown here) revealed that this assumption had been violated. Although there are a number of ways to deal with departure from multivariate normality, the straightforward strategy discussed by du Toit and du Toit (2001) is followed here. More specifically, these investigators report that departures from multivariate normality may be handled by converting raw scores on the observed indicators to normal scores prior to model estimation (du Toit & du Toit, 2001, p. 143). Following this recommendation, the analyses presented below are based on variables that have been normalized.

The substantive findings from this study are presented below in three sections. Findings from the analyses that focus on the relationship between spiritual connectedness and providing emotional support to fellow church members are examined first. Following this, the results from the models that were designed to examine the relationship between spiritual connectedness and tangible support, as well as spiritual connectedness and praying for others, are presented in the second and third sections, respectively.

Providing Emotional Support to Others

Fit of the Model to the Data

As discussed above, the data on spiritual connectedness and providing emotional support to fellow church members were gathered at two points in time. Consequently, two important issues must be addressed so that the model with the best fit to the data can be obtained. The first has to do with seeing whether the measurement error terms for identical indicators of spiritual connectedness and the provision of emotional support are correlated over time. Preliminary tests (not shown here) reveal that the measurement error terms were significantly correlated over time (a table containing the results of these findings are available from the first-listed author). The second issue has to do with assessing factorial invariance over time (Bollen 1989). Tests for factorial invariance assess whether the elements of the measurement model (i.e., the factor loadings and measurement error terms) are the same over time. Preliminary tests (not shown here) indicate that the factor loadings, but not the measurement error terms, were invariant over time. Although it would have been better to find that all the elements in the measurement model are invariant, Reise, Widaman, and Pugh (1993) argue that achieving even partial invariance is acceptable, and that meaningful interpretations can be made when examining the relationship between spiritual connectedness and providing emotional support to others.

The fit of the final model to the data is acceptable. More specifically, the Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI, Bentler & Bonett, 1980) estimate of .974 is well above the recommended cut point of .900. Similarly, the standardized root mean square residual estimate of .033 is below the recommended ceiling of .050 (SRMR, Kelloway, 1998). Finally, Bollen’s (1989) Incremental Fit Index (IFI) value of .988 is quite close to the ideal target value for this index (i.e., 1.0).

Psychometric Properties of the Observed Indictors

Table 2 contains the factor loadings and measurement error terms that were derived from the final model. These coefficients are important because they provide preliminary information on the psychometric properties of the multiple- item study measures. Although no firm guidelines are provided in the literature, Kline (2005) suggests that standardized factor loadings in excess of .600 tend to have reasonable reliability. As the data in Table 2 reveal, the standardized factor loadings range from .709 to .929, suggesting that the measures used in this study have good psychometric properties.

Table 2.

Measurement error parameter estimates for multiple item study measures (N = 556)

| Construct | Factor Loadinga | Measurement Errorb |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Spiritual connectedness (Wave 1) | ||

| A. Bond among all peoplec | .873 | .238 |

| B. How much we need each other | .859d | .262 |

| C. Recognize tremendous strength | .867 | .299 |

| 2. Emotional support provided to others (Wave 1) | ||

| A. Show someone love | .764 | .417 |

| B. Listen to private feelings | .709d | .498 |

| C. Express interest and concern | .843 | .290 |

| 3. Spiritual connectedness (Wave 2) | ||

| A. Bond among all people | .885 | .216 |

| B. How much we need each other | .929 | .136 |

| C. Recognize tremendous strength | .862 | .257 |

| 4. Emotional support provided to others (Wave 2) | ||

| A. Show someone love | .809 | .345 |

| B. Listen to private feelings | .729 | .469 |

| C. Express interest and concern | .856 | .267 |

Factor loadings are from the completely standardized solution. The first-listed item for each latent construct was fixed at 1.0 in the unstandardized solution.

Measurement error terms are from the completely standardized solution. All factor loadings and measurement error terms are significant at the .001 level.

Item content is paraphrased for the purpose of identification. See Table 1 for the complete text of each indicator.

The second- and third-listed items were constrained to be equivalent in the unstandardized solution for identical Wave 1 and Wave 2 measures.

Although the factor loadings and measurement error terms associated with the observed indicators provide useful information about the reliability of each item, it would be helpful to know something about the reliability of the scales as a whole. Fortunately, these estimates can be derived with a formula provided by DeShon (1998). This formula uses the factor loadings and measurement error terms provided in Table 2. Additional procedures described by Raykov (1998) make it possible to compute 95% confidence intervals (C. I.) for these reliability estimates, as well.

Applying the procedures described by DeShon (1998) and Raykov (1998) to the data in the current study yields the following reliability estimates and confidence intervals for the composite measures in Figure 1: Spiritual connectedness, Wave 1 (reliability = .892; lower C. I. = .877; upper C. I. = .908), emotional support provided to others, Wave 1 (reliability = .816; lower C. I. = .781; upper C. I. = .836), spiritual connectedness, Wave 2 (reliability = .992; lower C. I. = .907; upper C. I. = .931), and emotional support provided to others, Wave 2 (reliability = .841; lower C. I. = .811; upper C. I. = .859). As these estimates reveal, the reliability of the multiple-item constructs that are contained in Figure 1 is good.

Substantive Findings

The substantive findings that were derived from estimating the model depicted in Figure 1 are provided in Table 3. The results in Table 3 suggest that older adults who attend church more often tend to feel a stronger sense of spiritual connectedness with others at the baseline survey than older people who do not attend worship services as often (Beta = .225; p < .001). In addition, older individuals who go to church more often indicate that they provide more emotional support to the people they worship with. This is true with respect to the Wave 1 (Beta = .307; p < .001) and Wave 2 (Beta = .145; p < .001) measures of emotional support.

Table 3.

Spiritual connectedness and providing emotional support to others (N = 556)

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church Attendance (Wave 1) | Spiritual Connectedness (Wave 1) | Emotional Support (Wave 1) | Spiritual Connectedness (Wave 2) | Emotional Support (Wave 2) | |

| Age | .099*a | !.020 | !.044 | !.078 | !.068 |

| (.022)b | (!.002) | (!.005) | (!.006) | (!.008) | |

| Sex | !.056 | !.137** | !.063 | !.085* | .005 |

| (!.147) | (!.126) | (!.086) | (!.083) | (.007) | |

| Education | !.052 | !.069 | !.023 | .053 | !.026 |

| (!.020) | (!.009) | (!.005) | (.007) | (!.005) | |

| Race | .152*** | !.123** | !.144*** | !.102* | !.089* |

| (.384) | (!.110) | (!.191) | (!.096) | (!.122) | |

| Church attendance (Wave 1) | .225*** | .307*** | .051 | .145*** | |

| (.079) | (.160) | (.019) | (.078) | ||

| Spiritual connectedness (Wave 1) | .289*** | .304*** | !.027 | ||

| (.430) | (.322) | (!.042) | |||

| Emotional support (Wave 1) | .354*** | ||||

| (.363) | |||||

| Spiritual connectedness (Wave 2) | .372*** | ||||

| (.538) | |||||

| Multiple R2 | .035 | .091 | .249 | .136 | .388 |

Standardized regression coefficient

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

The data in Table 3 are consistent with the notion that a strong sense of spiritual connectedness forms the basis of providing emotional support to fellow church members. More specifically, the results indicate that a greater sense of spiritual connectedness is associated with providing more emotional support at Wave 1 (Beta = .289; p < .001). But the data suggest that the baseline measure of spiritual connectedness does not appear to be related to providing emotional support at Wave 2 (Beta = -.027; n.s.). Fortunately, the inconsistency in these results is clarified by examining the influence of spiritual connectedness at Wave 2. The results reveal that there is a fairly substantial relationship between spiritual connectedness at Wave 2 and providing emotional support to fellow church members at Wave 2 (Beta = .372; p < .001).

Taken as a whole, two potentially important conclusions emerge from the findings involving spiritual connectedness. First, the data indicate that change in spiritual connectedness is associated with change in providing emotional support to others. Second, the causal lag between spiritual connectedness and the provision of emotional support appears to be fairly brief. This second conclusion is based on the fact that the Wave 2 measure of spiritual connectedness is associated with the follow-up measure of emotional support but the Wave 1 spiritual connectedness measure fails to exert a statistically significant effect.

The data contained in Table 3 also provide evidence of the pervasive influence of race on religiousness in late life. However, the first result may initially appear to be at odds with what has been reported in the literature. More specifically, the data indicate that older Whites appear to attend church more often than older African Americans (Beta = .152; p < .001). An explanation for this unanticipated finding will be provided below when the findings that emerge from the model containing prayers for others are examined. This issue aside, the data in Table 3 also suggest that compared to older Whites, older Blacks have a stronger sense of spiritual connectedness with others and they are more likely to provide emotional support to the people in their congregation. This is true with respect to the Wave 1 (Beta = !.123; p < .01) and Wave 2 (Beta = !.102; p < .05) measures of spiritual connectedness as well as the Wave 1 (Beta = !.144; p < .001) and Wave 2 (Beta = !.089; p < .05) measures of emotional support.

Providing Tangible Help to Others

Fit of the Model to the Data

The model depicted in Figure 1 was re-estimated after the measures of providing tangible support to fellow church members were used in place of the indicators that assess providing emotional support to people at church. The results from the tests for correlated measurement error and factorial invariance over time (not shown here) reveal a pattern that is identical to the one reported in the previous section. More specifically, these tests indicate that the fit of the model to the data improved significantly when the measurement error terms for identical indicators of spiritual connectedness and tangible support were allowed to be correlated over time. Moreover, the factor loadings are invariant over time but the same is not true with respect to the measurement error terms. Once again, Model 3 provided the best fit to the data. The Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI, Bentler & Bonett, 1980) estimate of .922, the standardized root mean square residual estimate of .042, and the Incremental Fit Index (IFI; Bollen, 1989) value of .944 are all reasonably close to their respective recommended cut points.

Psychometric Properties of the Observed Indicators

An examination of the estimates that emerged from evaluating the model containing tangible help provided to others reveal that the standardized factor loadings (not shown here) ranged from .519 to .926. Only one was below the cut point of .600 that was recommended by Kline (2005). Additional calculations indicate that the reliability of the composite measure of providing tangible support to fellow church members at Wave 1 (reliability = .738; lower C. I. = .707; upper C. I. = .777) and Wave 2 (reliability = .860; lower C. I. = .846; upper C. I. = .883) is acceptable.

Substantive Findings

Table 4 contains the results from the analyses of the relationship between spiritual connectedness and providing tangible help to fellow church members. Taken as a whole, the findings are quite similar to the results that emerged when the provision of emotional support was in the model. More specifically, the data reveal that more frequent attendance at worship services is associated with a greater sense of spiritual connectedness at Wave 1 (Beta = .229; p < .001) as well as the provision of more tangible support to fellow church members at Wave 1 (Beta = .227; p < .001) and Wave 2 (Beta = .103; p < .05).

Table 4.

Spiritual connectedness and providing tangible support to others (N = 554)

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church Attendance (Wave 1) | Spiritual Connectedness (Wave 1) | Tangible Support (Wave 1) | Spiritual Connectedness (Wave 2) | Tangible Support (Wave 2) | |

| Age | .096*a | !.037 | !.107* | !.083* | !.088* |

| (.621)b | (!.003) | (!.013) | (!.007) | (!.013) | |

| Sex | !.058 | !.132** | .080 | !.073 | .122*** |

| (!.152) | (!.123) | (.112) | (!.071) | (.213) | |

| Education | !.058 | !.053* | .097 | .070 | .006 |

| (!.022) | (!.007) | (.019) | (.010) | (.002) | |

| Race | .144*** | !.127** | !.154*** | !.127** | !.024 |

| (.364) | (!.114) | (!.210) | (!.120) | (!.040) | |

| Church attendance (Wave 1) | .229*** | .227*** | .056 | .103* | |

| (.082) | (.122) | (.021) | (.068) | ||

| Spiritual connectedness (Wave 1) | .169*** | .305*** | !.042 | ||

| (.255) | (.319) | (!.078) | |||

| Tangible support (Wave 1) | .281*** | ||||

| (.349) | |||||

| Spiritual connectedness (Wave 2) | .180*** | ||||

| (.323) | |||||

| Multiple R2 | .032 | .090 | .123 | .144 | .167 |

Standardized regression coefficient

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

= p < .05;

= p < .01;

= p < .001.

The results also suggest that a deep sense of spiritual connectedness with others may have a significant influence on giving tangible help to people at church. The data provided in Table 4 indicate that a strong sense of spiritual connectedness is associated with providing more tangible help to fellow church members at the baseline interview (Beta = .169; p < .001). The same is true with respect to the data at Wave 2: Older people who feel a strong sense of spiritual connectedness with others are more likely to give tangible assistance to the people they worship with (Beta = .180; p < .001).

The data in Table 4 reveal that, once again, older Whites appear to attend worship services more often than older African Americans (Beta = .144; p < .001). The results also suggest that older Blacks appear to be more involved than older Whites in providing tangible support to their fellow church members. However, the results are not entirely consistent. More specifically, older African Americans report giving more tangible help to others at Wave 1 (Beta = !.127; p < .01) than older Whites, but race differences fail to emerge when change in tangible help over time is examined (Wave 2 Beta = !.024; n.s.).

Praying for Other People

Fit of the Model to the Data

The final set of analyses that were conducted for this study focus primarily on the relationship between spiritual connectedness and praying for others. Preliminary model assessment (not shown here) revealed that the measurement error terms associated with identical measures of spiritual connectedness over time are not significantly correlated over time. Moreover, further testing (not shown here) suggests that the factor loadings in the measurement model are invariant over time, but the measurement error terms are not invariant across the Wave 1 and Wave 2 interviews.

The goodness-of-fit information for the best model (Model 3) indicates that the fit to the data is good: The Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI, Bentler & Bonett, 1980) estimate of .989, the standardized root mean square residual estimate of .027, and the Incremental Fit Index (IFI; Bollen, 1989) value of .993 are all quite close to their respective target values.

Psychometric Properties of the Observed Indicators

The standardized factor loadings that emerged from the model that contains praying for others range from .835 to .927. Because praying for others is assessed with a single item, it is not possible to derive an internal consistency reliability estimate for this construct.

Substantive Findings

The substantive findings from the model that contained praying for others are provided in Table 5. It comes as no surprise to find that older people who go to church frequently often pray for others. This is true with respect to praying for others at the baseline (Beta = .232; p < .001) and follow-up interviews (Beta = .124; p < .001).

Table 5.

Spiritual connectedness and praying for others (N = 854)

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church Attendance (Wave 1) | Spiritual Connectedness (Wave 1) | Praying for Others (Wave 1) | Spiritual Connectedness (Wave 2) | Praying for Others (Wave 2) | |

| Age | !.036a | !.001 | .037 | .001 | !.005 |

| (!.015)b | (!.000) | (.013) | (.000) | (!.002) | |

| Sex | !.100** | !.140*** | !.171*** | !.081** | !.095*** |

| (!.528) | (!.160) | (!.758) | (!.100) | (!.383) | |

| Education | .113*** | !.087** | !.042 | .069* | !.013 |

| (.085) | (!.014) | (!.026) | (.012) | (!.008) | |

| Race | !.126*** | !.152*** | !.177*** | !.125*** | !.107*** |

| (!.643) | (!.167) | (!.762) | (!.149) | (!.416) | |

| Church attendance (Wave 1) | .377*** | .232*** | .111** | .124*** | |

| (.081) | (.195) | (.026) | (.094) | ||

| Spiritual connectedness (Wave 1) | .341*** | .384*** | .064 | ||

| (1.333) | (.416) | (.225) | |||

| Praying for others (Wave 1) | .272*** | ||||

| (.246) | |||||

| Spiritual connectedness (Wave 2) | .290*** | ||||

| (.950) | |||||

| Multiple R2 | .033 | .220 | .373 | .252 | .400 |

Standardized regression coefficient

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

= p < .05;

= p < .01;

= p < .001.

The data in Table 6 also indicate that a strong sense of spiritual connectedness at the Wave 1 survey is associated with more frequent prayers on behalf of others at Wave 1 (Beta = .341; p < .001), but not Wave 2 (Beta = .064; n.s.). However, the results further reveal that older adults who feel a strong sense of connectedness with other people at Wave 2 are more likely to report praying for others at Wave 2 (Beta = .290; p < .001) than older people who do not feel a close sense of spiritual connectedness with others.

An unanticipated finding emerged when the models for providing both emotional and tangible support to others were evaluated. Recall that the results appeared to suggest that older Whites attend worship services more often than older Blacks (see Tables 3 and 4). However, the results contained in Table 5 help to clarify this issue. As discussed earlier, the items that assess providing emotional and tangible support to others were only administered to older study participants who attend worship services more than twice a year. This means that the analyses involving emotional and tangible support were conducted only with older people who attend church on a regular basis. In contrast, the items that assess praying for others were administered to all older study participants regardless of whether they go to church or not. When data from the full range of church attendance are included in the analyses, the findings fall in line with what is reported in the literature. More specifically, as the findings in Table 5 reveal, older Whites are less likely to attend church services than older African Americans (Beta = !.126; p < .001).

The data in Table 5 also suggest that older Blacks are more likely than their older White counterparts to pray for other people. This is true with respect to the baseline (Beta = !.177; p < .001) and follow-up (Beta = !.107; p < .001) interview data.

Conclusions

There is some evidence that social support exchanged in the church has more beneficial effects on health and well-being than assistance provided by secular social network members (Krause, 2006a). Moreover, research reveals that giving support to fellow church members may have a more beneficial effect on the health of support providers than receiving assistance from people at church (Krause, 2006b). The current study builds upon these findings by exploring the underlying belief structure that forms the basis of helping other people. A new construct B spiritual connectedness B was introduced to facilitate this work. Findings from a nationwide, longitudinal survey reveal that older adults who believe there is a strong sense of connectedness among all people are more likely to help others than older individuals who do not feel that their lives are bound up with the lives of other individuals. Three measures of helping others were evaluated: providing emotional support to fellow church members, giving tangible help to coreligionists, and praying for other individuals. Evaluating a range of outcomes serves two important functions. First, it expands the scope of inquiry by showing that the influence of spiritual connectedness is not restricted to one type of helping behavior only. Second, including prayers for others helps show that the effects of a sense of spiritual connectedness may extend beyond immediate church members to individuals in the wider social world.

In the process of conducting this study, an effort was made to focus on the more dynamic aspects of the relationship between spiritual connectedness and helping others. The data consistently reveal that change in spiritual connectedness over time is associated with change in helping others. By digging deeper into the factors that shape the provision of assistance to others, the findings from the current study serve to unearth some of the more basic functions of religion and help bring investigators a step closer to understanding the elusive chain of mechanisms that drive the relationship between religion and health in late life. This appears to be the first time that the relationship between spiritual connectedness and helping others has been evaluated empirically.

The next steps in pursuing this research agenda are straightforward. In particular, researchers need to empirically evaluate other factors that shape feelings of spiritual connectedness. A preliminary first step was taken in the current study by providing evidence that older people who attend worship services more often are more likely to feel a close sense of spiritual connectedness with others. But worship services are complex events that involve a number of factors including group prayers, individual prayers, sermons, and hymns. Any (or all) of these factors could promote a strong sense of spiritual connectedness with others. Other factors, including reading the Bible at home or watching religious programs on television or listening to them on the radio may play a role, as well. Participation in Bible study and prayer groups may also influence a sense of spiritual connectedness.

Researchers may benefit from bringing age differences to the foreground. As the theoretical rationale that was presented earlier reveals, older people are at a developmental stage in which social relationships may take on increasing importance. This suggests that the relationship between spiritual support and helping others may be stronger among older rather than younger people. Pursuing the study of age differences in the relationship between spiritual connectedness and helping others may help to infuse work in this area with a much needed life course perspective.

Finally, researchers should consider studying the relationship between spiritual connectedness and a wider range of helping behaviors. More specifically, it would be useful to assess whether feelings of spiritual connectedness are associated with the provision of emotional and tangible help to people outside the church. Unfortunately, measures of these helping behaviors were not available in the current study. It would also be helpful to see whether a sense of spiritual connectedness is associated with the decision to perform volunteer work in formal programs designed to help people who are in need.

In the process of exploring these as well as other issues it is important that researchers keep the limitations of the current study in mind. One shortcoming may be especially consequential. Even though the data in the current study were gathered at more than one point in time, the findings do not conclusively demonstrate that a sense of spiritual connectedness “causes” older people to help others more often. In fact, one might just as easily reverse the causal ordering and argue that in the process of helping others, older adults become more aware of the connectedness and interdependence that exists among all people. This issue can only be resolved conclusively with data that have been obtained from a true experiment. However, it is difficult to imagine how an experiment could be designed to disentangle the relationship between spiritual connectedness and helping others in late life.

George Albert Coe was one of the early founders of the psychology of religion. Writing in 1902, he attempted to distill the essence of Christianity. Sounding more sociological than psychological, he argued that the goal of becoming a Christian “… is to be completely human, to be completely ourselves, but to remember that this is possible only through participation in the life of our fellows. The end of the individual life is perfected in community life” (Coe, 1902, p. 172). When viewed at the broadest level, the intent of the current study was to assess one way in which these lofty goals might be attained. Based on a world view that emphasizes the interdependence and interconnectedness among all people (i.e., spiritual connectedness), it was possible to show how one key element of effective community life (i.e., helping others) arises.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG014749)

Contributor Information

Neal Krause, The University of Michigan.

Elena Bastida, The University of Texas Pan American.

References

- Baldwin JA, Hopkins R. African-American and European-American cultural differences as assessed by the Worldviews Paradigm: An empirical analysis. Western Journal of Black Studies. 1990;14:38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Barna G. The state of the church, 2002. Ventura, CA: Issachar Resources; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness-of-fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–600. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:331–338. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe GA. The religion of a mature mind. Chicago: Fleming H Revell Company; 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH. Life and the student: Roadside notes on human nature, society, and letters. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JD. Patterns of belief at the denominational and congregational levels. Review of Religious Research. 1972;13:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- DeShon RP. A cautionary note on measurement error correlations in structural equation models. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:412–423. [Google Scholar]

- du Toit M, du Toit S. Interactive LISREL: User’s guide. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dulin PL. Social support as a moderator of the relationship between religious participation and psychological distress in a sample of community dwelling older adults. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2005;8:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Boardman JD, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Religious involvement, stress, and mental health: Findings from the 1995 Detroit Area Study. Social Forces. 2001;80:215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, George LK. Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a Southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33:46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and further directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala WE, Bjorck JP, Gorsuch R. The religious support scale: Construction, validation, and cross-validation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:761–786. doi: 10.1023/A:1020264718397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel SA. Causal analysis with panel data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup G, Lindsay DM. Surveying the religious landscape: Trends in U. S. beliefs. Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Tourangeau R. Survey methodology. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BE, Linden W, Najarian B. Social support interventions: Do they work? Clinical Psychological Review. 2002;22:381–440. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, King VL, Neufeld K, Stoller KB, Peirce J, Brooner RK. Involving significant others in the care of opioid-dependent patients receiving methodone. Journal of Substance Abuse and Treatment. 2005;29:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg L. Stages and aging in moral development B some speculations. The Gerontologis. 1973;13:497–502. doi: 10.1093/geront/13.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring race differences in a comprehensive battery of church-based social support measures. Review of Religious Research. 2002a;44:126–149. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002b;57B:S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. A comprehensive strategy for developing closed-ended survey items for use in studies of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002c;57B:S263–S274. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.s263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Praying for others, financial strain, and physical health status in late life. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;24:377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based and secular social support on self-rated health in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2006a;61B:S35–S43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and mortality. Journal of Gerontology: Social Science. 2006b;61B:S140–S146. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Altruism, religion, and health: Exploring the ways in which helping others benefits support providers. In: Post SG, editor. Altruism and health: Perspectives and empirical findings. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 410–421. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson MR, Jennings PA, Aldwin CM, Shiraishi RW. Self-transcendence: Conceptualization and measurement. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2005;60:127–143. doi: 10.2190/XRXM-FYRA-7U0X-GRC0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI. Patterns and psychological correlates of material support within a religious setting: The bidirectional support hypothesis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Jagers RJ. A relational framework for the study of religiosity and spirituality in the lives of African Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:519–539. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Murray YF, Hatcher CA, Hearn KD, Lawhon CD, Murphy EJ, Washington TA. Religiosity, spirituality, and the subjective quality of African American men=s friendships: An exploratory study. Journal of Adult Development. 2001;8:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard-Reid PU. Diverse worship: African-American, Caribbean, and Hispanic perspectives. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin ML, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Menard S. Longitudinal research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen HM, Nelsen AK. Black church in the sixties. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JA, Yates BD, Atwood JR, Hertzog M. Effects of a physical activity intervention for women. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27:93–110. doi: 10.1177/0193945904270912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raykov T. A method for obtaining standard errors and confidence intervals of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1998;22:369–374. [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Widaman KF, Pugh RH. Confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Two approaches for exploring measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:552–566. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JD. Black religion, black theology. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ross EA. Social control V.: Religion. American Journal of Sociology. 1896;2:433–445. [Google Scholar]

- Russell B. A free man’s worship. In: Klemke ED, editor. The meaning of life. New York: Oxford University Press; 1957/2000. pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rye MS, Pargament KI, Ali MA, Beck GL, Dorff EN, Hallisey C, Narayanan V, Williams JG. Religious perspectives on forgiveness. In: McCullough ME, Pargament KI, Thoresen E, editors. Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Guilford; 2000. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel G. A contribution to the sociology of religion. In: Helle HJ, editor. Essays on religion: Georg Simmel. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1898/1997. pp. 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Finke R. Acts of faith: Explaining the human side of religion. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology. 1982;33:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Chatters LM. Supportive relationships with church members among African Americans. Family Relations. 2005;54:501–511. [Google Scholar]

- Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence: A developmental theory of positive aging. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow R. Acts of compassion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]