Abstract

Deregulated innate immune responses that result in increased levels of type I interferons (IFNs) and stimulation of IFN-inducible genes are thought to contribute to chronic inflammation and autoimmunity. One family of IFN-inducible genes is the Ifi200 family, which includes the murine (eg, Ifi202a, Ifi202b, Ifi203, Ifi204, Mndal, and Aim2) and human (eg, IFI16, MNDA, IFIX, and AIM2) genes. Genes in the family encode structurally related proteins (the p200-family proteins), which share at least one partially conserved repeat of 200-amino acid (200-AA) residues. Consistent with the presence of 2 consecutive oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding folds in the repeat, the p200-family proteins can bind to DNA. Additionally, these proteins (except the p202 proteins) also contain a pyrin (PYD) domain in the N-terminus. Increased expression of p202 proteins in certain strains of female mice is associated with lupus-like disease. Interestingly, only the Aim2 protein is conserved between the mouse and humans. Several recent studies have provided evidence that the Aim2 and p202 proteins can recognize DNA in cytoplasm and the Aim2 protein upon sensing DNA can form a caspase-1-activating inflammasome. In this review, we discuss how the ability of p200-family proteins to sense cytoplasmic DNA may contribute to the development of chronic inflammation and associated diseases.

Introduction

Innate immune responses, which control infections, also elicit the T- and B-cell responses of adaptive immunity (Janeway and Medzhitov 2002; Eisenbarth and Flavell 2009; Kanta and Mohan 2009; Munz and others 2009; Stetson 2009). In response to infections, production of type I interferons (IFNs) is part of an innate immune response (Stark and others 1999; Stetson and Medzhitov 2006). The IFNs are a family of cytokines (Sen and Lengyel 1992; Stark and others 1999). The family includes type I (IFN-α, IFN-β, and others) and type II (IFN-γ) IFNs. All type I IFNs signal through a common cell surface receptor to activate a set of inducible genes that are thought to carry out the biological and immuno-modulatory activities (Stark and others 1999). The immuno-modulatory activities of the type I IFNs are central to innate and adaptive immune responses (Theofilopoulos and others 2005; Banchereau and Pascual 2006).

Innate immune responses, which result in an excessive production of the type I IFNs and activation of IFN-inducible genes, have been implicated in the development of autoimmune pathologies (Crow and Wohlgemuth 2003; Baechler and others 2004; Theofilopoulos and others 2005; Banchereau and Pascual 2006). Additionally, tissue damage, either as a result of infections or sterile injuries, could be the source of apoptotic debris and, thus, autoantigen, which in turn, can induce the type I IFN production (Banchereau and others 2004; Marshak-Rothstein 2006; Baccala and others 2007, 2009). Consistent with these observations, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients and murine models of spontaneous lupus-like disease develop peripheral blood gene expression profile characterized by an “IFN-α signature” (Crow and Wohlgemuth 2003; Baechler and others 2004; Theofilopoulos and others 2005; Banchereau and Pascual 2006; Lu and others 2007). This signature is thought to reflect increased serum levels of the type I IFNs. Moreover, the severity of systemic autoimmune diseases, such as SLE and Sjogren's syndrome (SS), is correlated well with high levels of inflammatory cytokines (Theofilopoulos and others 2005; Banchereau and Pascual 2006). This is because autoantibodies against the nuclear antigens are known to form immune complexes with ubiquitous antigens, which are thought to result in production of proinflammatory cytokines, including the type I IFNs (Marshak-Rothstein 2006; Baccala and others 2007, 2009; Keith and others 2007). The increased levels of IFN-α up-regulate TLR expression, extend the activated T-cell response, enhance humoral immunity, and promote antigen presentation (Marshak-Rothstein 2006; Baccala and others 2007). If continued unregulated, these IFN-induced responses can be pathological. As a consequence, systemic autoimmune diseases could result from continuous inflammatory responses that initiate a vicious feedback amplification loop of autoreactive pathological responses (Baccala and others 2007, 2009; Bolland and Garcia-Sastre 2009).

One family of IFN-inducible proteins is the p200-family (Lengyel and others 1995; Johnstone and Trapani 1999). The family includes structurally and functionally related murine and human proteins. Initially, we grouped these proteins in a family because all proteins contain at least one partially conserved repeat of 200-amino acid residues and referred to these proteins as p200-proteins (Lengyel and others 1995). Others in the field adopted a different nomenclature and named these proteins as HIN-200 (hematopoietic IFN-inducible nuclear proteins with 200-amino acids) proteins (Johnstone and Trapani 1999). However, several studies have provided evidence that the HIN-200 nomenclature is inappropriate: expression of several p200-family proteins is not restricted to hematopoietic cells and their expression can be regulated by numerous other signaling pathways (other than IFNs), and some proteins are both cytoplasmic and nuclear (Choubey 2000; Choubey and Kotzin 2002; Choubey and Panchanathan 2008). Considering the above observations, we propose here that the p200-family proteins should be referred as “p200-proteins.”

Several reviews have described the chromosomal location, genomic structure, and evolutionary relatedness of the murine and human Ifi200-family genes (Lengyel and others 1995; Choubey 2000; Ludlow and others 2005). Other reviews have focused on the role of Ifi200-family genes and the corresponding proteins in interferon action (Landolfo and others 1998; Asefa and others 2004). Additionally, there are recent reviews that have focused on the role of p200-family proteins in cell growth regulation and autoimmunity (Choubey and Kotzin 2002; Choubey and Panchanathan 2008). In this review, we focus on DNA-sensing cytoplasmic p200-family proteins and discuss how regulation of their expression and subcellular localization in immune cells may provide important molecular links between chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases.

The p200-family proteins

The p200-family proteins are encoded by the IFN-inducible murine (eg, Ifi202a, Ifi202b, Ifi203, Ifi204, Mndal, and Aim2) and human (eg, IFI16, IFIX, MNDA, and AIM2) genes (Lengyel and others 1995; Johnstone and Trapani 1999; Choubey and Panchanathan 2008; Zhang and others 2009). As stated above, these proteins share either 1 or 2 partially conserved repeats of 200-amino acid residues (200-AA repeat) toward the C-terminus. Based on amino acids identity within the repeats found in the p200-proteins, the repeat is designated as A, B, or C type (Lengyel and others 1995; Choubey 2000; Ludlow and others 2005). Surprisingly, only the Aim2 protein in the family appears to be conserved (55% amino acid identities) between mouse and humans (Fig. 1) and other murine proteins, such as p202a and p202b, do not appear to have human homologs (Ludlow and others 2005). Most p200-family proteins (except the p202a and p202b proteins) that are characterized to some extents also contain a pyrin (PYD) domain in the N-terminus (Choubey 2000; Choubey and Kotzin 2002; Ludlow and others 2005). Increased expression of p200-family proteins in a variety of cultured cells and in vivo is known to retard cell proliferation, modulate cell survival, and promote differentiation in certain cell types (Choubey 2000; Choubey and Kotzin 2002; Ludlow and others 2005; Choubey and Panchanathan 2008). Recent reports have provided evidence that the murine (eg, p202 and Aim2) and human (eg, AIM2) p200-family proteins can recognize DNA in cytoplasm (Bürckstümmer and others 2009; Fernandes-Alnemri and others 2009; Hornung and others 2009; Krieg 2009; Roberts and others 2009; Schroder and others 2009). Moreover, instead of inducing type I IFN, binding of AIM2 protein to DNA appears to generate a novel inflammasome that induces maturation of proinflammatory cytokines (Krieg 2009; Schroder and others 2009) (see below).

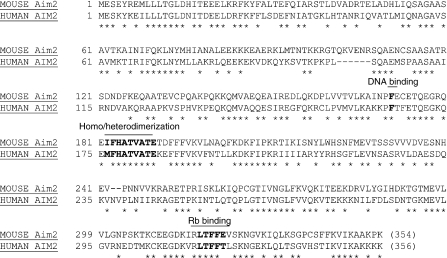

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of the murine (Aim2; the NCBI accession # NP001013801) and human (AIM2; accession #AAH10940) absent in melanoma 2 proteins. The amino acid residues that are identical between the 2 proteins are indicted by asterisks (*). The amino acid residues of a protein–protein interaction motif [(I/M) (F/L) HATVA (T/S)], which is conserved in all 200-AA repeats in the p200-family proteins, and a potential pRb-binding motif (LxCxE-like motif) are shown in bold. Substitution of phenylalanine (Phe165) with alanine (Ala) amino acid residue in human AIM2 protein, which resulted in diminished DNA binding (Bürckstümmer and others 2009), is also indicated in bold. This Phe residue is conserved between the murine and human absent in melanoma 2 proteins.

The 200-AA domain

The 200-AA domain in the murine p202 (and in other p200-proteins) has been shown to mediate protein–protein interactions through at least 2 specific motifs: the conserved MFHATVAT motif and the LxCxE pRb-binding motif (Fig. 2; Choubey 2000; Choubey and Kotzin 2002; Ludlow and others 2005). The p202a protein can homodimerize through the MFHATVAT motif and the homodimerization is disrupted by a mutation of the histidine (His) residue (Koul and others 1998). Similarly, binding of 53BP1 protein to p202a is abrogated by the His-mutation (Datta and others 1996).

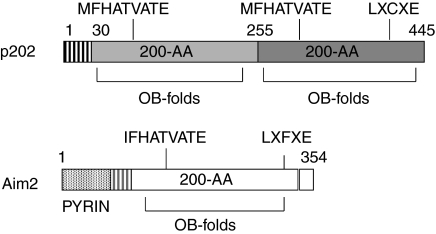

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of structural and functional domains in the murine p202 and Aim2 proteins. Vertical line box in the N-terminus of the p202 protein denotes a unique region that is not conserved between p202 and Aim2 proteins. Light gray and dark gray boxes in the p202 protein denote a type-A and a type-B 200-AA repeat, respectively (Ludlow and others 2005). White box in the Aim2 protein denotes a type-C 200-AA repeat. The A-type repeat in the p202 protein shares 24.4% amino acid identity with the B repeat and 35.5% amino acid identity with the C repeat in the Aim2 protein. In contrast, the B repeat in p202 protein shares 33.3% amino acid identity with the C repeat in the Aim2 protein. Dotted box in the N-terminus of the Aim2 protein denotes the pyrin (PYD) domain. Each 200-AA repeat is predicted to contain 2 consecutive OB-folds (Albrecht and others 2005). The amino acid residues of a protein–protein interaction motif [(I/M) (F/L) HATVA (T/S)] and a potential pRb-binding motif (LxCxE-like motif) are also shown.

Interestingly, our analyses of amino acid residues in the 200-AA domains in the 200-family proteins revealed that the domain contains 2 consecutive oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding folds (OB-folds) (Fig. 2; Albrecht and others 2005). The OB-folds are found in other proteins that are known to bind either single- or double-stranded DNA (Bochkarev and Bochkareva 2004). Consistent with the presence of 2 OB-folds in the 200-AA domain, the p202 proteins (p202a and p202b), which primarily contain two 200-AA domains, can bind to single- or double-stranded DNA in vitro (Choubey and Gutterman 1996). Similarly, the IFI16 protein can also bind to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) with higher affinity than dsDNA (Yan and others 2008). Moreover, the hypophosphorylated form of the p202 protein(s) binds DNA with higher affinity (Choubey and Gutterman 1996). Additionally, in interferon-treated MEFs in metaphase, the p202 protein(s) associated with chromosomes (Choubey and Lengyel 1993). Together, the above observations suggest that the presence of 200-AA domain in the p200-proteins allows these proteins to sense DNA and interact with other proteins. Consequently, the ability of p200-proteins to sense DNA or interact with other proteins is likely to depend on their subcellular localization-dependent access to DNA and levels of other interacting proteins.

The pyrin domain

The PYD domain (also referred as PAAD or DAPIN) in proteins comprises a bundle of 5 or 6 α-helices (Aravind and others 2001; Reed and others 2003; Stehlik and Reed 2004). The domain is found in numerous vertebrate proteins and functions as homotypic protein–protein interaction domain. In most pyrin family proteins, the PYD domain is found in combination with other structural domains, such as caspase recruitment domain (CARD), which is commonly found in mediators of innate immunity and apoptosis (Reed and others 2003; Stehlik and Reed 2004). In the p200-family proteins, the PYD domain is found in combination with the 200-AA domain (Fig. 2).

Interestingly, the PYD domain-containing proteins have been implicated in the regulation of a variety of physiologic responses, including cytokine responses, apoptosis, inflammation, and autoimmunity (Reed and others 2003; Stehlik and Reed 2004). These proteins are thought to regulate the above physiologic responses through activation of inflammatory caspases (eg, caspase-1) and transcription factor NF-κB (McConnell and Vertino 2004). Some of the pyrin family proteins are known to bind apoptotic speck protein containing a CARD (ASC), a proapoptotic protein that induces the formation of large cytoplasmic “specks” in cells and activates pro-caspase-1. Hereditary mutations in certain genes encoding the pyrin family proteins have been implicated in autoinflammatory syndromes, thus, supporting their role in the regulation of various inflammatory responses (Franchi and others 2009). The presence of the PYD domain in the p200-family proteins may be consistent with their role in modulation of apoptosis and inflammation (Reed and others 2003; Stehlik and Reed 2004; Ludlow and others 2005).

Subcellular localization of p200-family proteins

Using complementary approaches such as detection of endogenous levels of proteins by indirect immunofluorescence and cell fractionation followed by immunoblotting, basal uninduced levels of the most p200-family proteins (eg, p203, p204, IFI16, and MNDA) are primarily detected in nucleus (Choubey 2000; Ludlow and others 2005). The nuclear localization of these p200-family proteins is consistent with the presence of a classical nuclear localization signal (NLS). In contrast, depending upon cell context and when overexpressed in cultured cells, p202a and human AIM2 proteins are primarily detected in the cytoplasm (Choubey 2000; Choubey and others 2000). The cytoplasmic subcellular localization of the p202a and AIM2 proteins is consistent with the lack of a classical NLS in these proteins. Intriguingly, in IFN-γ-treated human HL-60 cells, which resulted in increase in steady-state levels of the human AIM2 protein, the bulk of the protein was primarily detected in the nucleus (Cresswell and others 2005). Moreover, the constitutive levels of the p202 protein are primarily detected in the cytoplasm of B6.Nba2 MEFs and IFN-α treatment of the MEFs potentiates the nuclear accumulation of the protein (Choubey and others 2003). In IFN-treated mouse AKR-2B fibroblasts, the endogenous levels of p202 protein (possibly both p202a and p202b) are detected both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus using indirect immunofluorescence and cell fractionation approaches (Choubey and Lengyel 1993). Consistent with the presence of a mitochondrial targeting sequence in the p202a protein in the N-terminus, in the cytoplasm, a significant fraction of the p202a protein was associated with the mitochondria (Choubey and Lengyel 1993; Choubey and others 2003). Moreover, a GFP-p202a fusion protein colocalizes with a mitochondrial dye (Choubey and others 2003). Additionally, large increases in the levels of p202 protein during in vitro differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts are associated with its translocation into the cytoplasm (Datta and others 1998). Considering the above observations, it seems likely that, in certain cell types, the IFN treatment of cells potentiates the nuclear localization of the human AIM2 and mouse p202 (possibly both p202a and p202b) proteins. Importantly, the extent of cytoplasmic localization of AIM2 and p202 proteins in the cytosol and various membranous compartments has important consequences for DNA accessibility and it can also affect the downstream signaling that results in modulation of the transcriptional activity of NF-κB (see below).

The human and mouse absent in melanoma 2 genes and the encoded proteins

The AIM2 gene was originally identified as a novel gene that is differentially expressed in a human malignant melanoma cell line UACC903 that had received chromosome 6, resulting in restoration of AIM2 expression and reversion of the malignant phenotype (DeYoung and others 1997). Consistent with a role for the AIM2 gene in tumor suppression, the gene is reported to contain a microsatellite instability site that results in inactivation of the gene in ∼47% of colorectal tumors with high microsatellite instability (Woerner and others 2007). Additionally, mutations in the AIM2 gene have also been associated with the development of gastric and endometrial cancers (Hasegava and others 2002). It has been reported that the AIM2 gene is frequently silenced by DNA methylation (Woerner and others 2007). Furthermore, steady-state levels of AIM2 mRNA are decreased in human fibroblasts derived from Li-Fraumeni patients following their immortalization (Fridman and others 2006). Together, these reports may suggest that the loss of absent in melanoma 2 protein functions in cells provides growth advantage to tumor cells.

A study has indicated that forced increased expression of AIM2 protein in human breast cancer cell lines can suppress cell proliferation and tumorigenicity (Chen and others 2006). Moreover, increased expression of the AIM2 protein inhibited mammary tumor growth in an orthotopic tumor model. The study also reported that increased levels of AIM2 protein in breast cancer cells increased apoptosis. Interestingly, susceptibility to apoptosis was associated with inhibition of the transcriptional activity of NF-κB and desensitization of NF-κB to TNF-α-mediated activation (Chen and others 2006). Intriguingly, increased expression of human AIM2 protein in human melanoma cells line UACC903 did not result in inhibition of cell proliferation or alteration in cell survival (Cresswell and others 2005). Moreover, the AIM2 protein was reported to homodimerize through the PYD domain and heterodimerize with the IFI16 protein (Cresswell and others 2005).

In murine AKR-2B fibroblasts, ectopic expression of human AIM2 protein resulted in localization of the protein primarily in the cytoplasm (Choubey and others 2000). Moreover, increased expression of the AIM2 protein in cells, under reduced serum conditions, enhanced the susceptibility to apoptosis. Moreover, the human AIM2 protein can dimerize with the murine p202 protein in vitro (Choubey and others 2000).

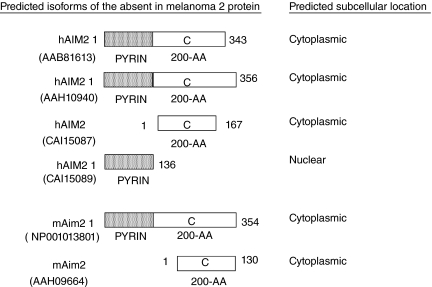

Previous searches of the NCBI database for the mouse homologue of the human AIM2 gene had predicted the presence of a related gene (Ludlow and others 2005). Accordingly, a study reported nucleotide sequence for a cDNA encoding a form of mouse Aim2 protein and compared the nucleotide sequence with the human AIM2 cDNA sequence (Fernandes-Alnemri and others 2009). Moreover, a recent search of the NCBI database for human AIM2 protein sequence resulted in 9 entries predicting 4 isoforms of the protein, one of which lacks the PYD domain and is predicted to be nuclear in localization (Fig. 3). Similarly, a search for the murine Aim2 protein sequences in the NCBI data base revealed entries predicting 2 isoforms of the murine Aim2 protein (Fig. 3). Together, these predicted isoforms of the human and murine absent in melanoma 2 proteins raise the possibility that these isoforms may be expressed in a cell type-dependent manner. Importantly, these various isoforms of the AIM2 and Aim2 proteins are predicted to vary with respect to their subcellular localization (Table 1). Consequently, it seems likely that these proteins will vary with respect to their ability to access DNA in the cytoplasm and interact with other proteins. Therefore, further work will be needed to resolve this important issue.

FIG. 3.

Schematic structural representation of the predicted isoforms of the human and murine absent in melanoma 2 proteins and their predicted overall subcellular localization. The NCBI accession numbers for the isoforms are indicated in parenthesis. Dotted box in the N-terminus of the Aim2 protein denotes the pyrin (PYD) domain. White box in the Aim2 protein denotes the type-C 200-AA repeat.

Table 1.

Predicted Sub-cellular Localization of Various Isoforms of the Absent in Melanoma 2 Protein

| Protein accession # No. of AA | Mouse Aim2 NP_001013801 1 to 354 | Human AIM2NM_004833.1 1 to 343 | Human AIM2 BC010940.1 1–356 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoplasmic | 82.6% | 34.8% | 56.5% |

| Cytoskeletal | — | — | 8.7% |

| Extracellular | — | — | 4.3% |

| Nuclear | 8.7% | 21.7% | 17.4% |

| Mitochondrial | 8.7% | 26.1% | 4.3% |

| Vacuolar | — | 8.7% | — |

| ER | — | 4.3% | 4.3% |

| Golgi | — | — | 4.3% |

| Peroxysomal | — | 4.3% | — |

| Prediction | Cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic |

Expression patterns and regulation

Expression of Ifi202 (Ifi202a and Ifi202b) mRNA is detectable in a variety of adult mouse tissues (Wang and others 1999). Basal steady-state levels of the Ifi202a and Ifi202b mRNAs are also detectable in splenic cells from lupus-prone B6.Nba2 mice (Choubey 2008). Expression of Ifi202 is up-regulated by type I or type II IFN through IFN-responsive cis elements termed interferon-stimulated response elements (ISRE) in the promoter region (Gribaudo and others 1987).

Steady-state levels of Ifi202 mRNA in splenic cells from B6 or NZW mice are at least ∼100–200-fold lower than the B6.Nba2 or NZB mice (Rozzo and others 2001; Choubey and Kotzin 2002). A comparison of the 5′-regulatory region of the Ifi202 gene among various strains of mice revealed several sequence polymorphisms (Rozzo and others 2001; Choubey and Kotzin 2002). Notably, a single nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter region of the Ifi202 gene in the NZB allele results in a TATA box, a transcription initiation consensus sequence (White and Jackson 1992). Consistent with the presence of a TATA box in the NZB allele of the Ifi202 gene, it was noted that the activity of 202-luc-reporter containing the NZB-derived promoter region was significantly higher than the 202-luc-reporter containing the B6-derived promoter region (Choubey and Panchanathan 2008). These observations demonstrated that the promoter polymorphisms contribute to increased expression of the Ifi202 gene in certain lupus-prone strains of mice.

Mechanisms independent of the IFN signaling are also known to regulate Ifi202 expression (Choubey and Kotzin 2002; Choubey and Panchanathan 2008). We have noted that NZB splenocytes, which are deficient in the type I IFN receptor signaling, express p202 levels that are comparable with the age-matched wild-type mice (Santiago-Raber and others 2003). Moreover, B6.Nba2 mice deficient in the IFN type I receptor signaling had steady-state levels of Ifi202 mRNA reduced by only 2-fold than the wild-type mice (Jϕrgensen and others 2007). Furthermore, in B6.Nba2 splenocytes, levels of Ifi202 mRNA and protein are up-regulated by IL-6 (Pramanik and others 2004). There is also evidence that expression of the Ifi202 is regulated in gender-dependent manner (Gubbels and others 2005). Consistent with this observation, the physiological estrogen 17β-estradiol (E2) in murine uterus up-regulates Ifi202 expression by ∼8-fold (Moggs and others 2004). Moreover, we have found that expression of Ifi202 gene is differentially regulated by the male and female sex hormones in splenic cells from certain strains of mice (Panchanathan and others 2009).

The human AIM2 gene is reported to be constitutively expressed in the spleen, small intestine, and peripheral leukocytes (DeYoung and others 1997). Moreover, IFN-γ treatment of human HL-60 cell line is reported to increase steady-state levels of AIM2 mRNA and protein (Cresswell and others 2005). Similarly, IFN-β treatment of human THP-1 cell line is also reported to increase steady-state levels of the AIM2 mRNA (Bürckstümmer and others 2009). However, it remains unclear how type I or type II IFN treatment of cells increases the steady-state levels of AIM2 mRNA (and possibly proteins) in human cell lines. Furthermore, it remains to be determined whether IFN (type I or type II) treatment of the murine cells activates transcription of the Aim2 gene. Given that the most IFN responses vary among different cell types and are further modulated by various signaling pathways (Platanias 2005), it seems likely that the expression of human AIM2 and mouse Aim2 is IFN-responsive and is modulated by related signaling pathways. Therefore, stimulation of Ifi200-family genes by the type I IFNs is likely to regulate signaling pathways that affect innate immune responses.

DNA-sensing proteins and innate immune responses

An inflammatory response that is initiated by recognition of self-DNA in cytosol has been implicated in autoimmune diseases, such as SLE (Muruve and others 2008; Vilaysane and Muruve 2009). TLR9, the only known primary sensor of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), recognizes unmethylated CpG motifs in DNA (Kumagai and others 2008). Although, TLRs are important for detection of nucleic acids in cells, they are only expressed in a subset of cells, while almost all nucleated cell types can activate type I IFN response to viral DNA (Deane and Bolland 2006). Consistent with the idea that other type of sensors must exist to detect DNA in cytoplasm, recent studies have provided evidence that cytoplasmic DNA also triggers an innate immune response (Ishii and others 2006). For example, intracellular administration of double-stranded B-form of DNA in murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) induces interferon production (Ishii and others 2006). The induction is TLR-independent, but dependent upon activation of NF-κB and IRF3. However, in macrophages, cytosolic DNA activates a potent type I interferon response. In this case, the response is TLR-independent, but IRF3-dependent (Ishii and others 2006). Although MEFs and macrophages use different signaling molecules and pathways, the presence of exogenous DNA in cytoplasm ultimately activates transcription of the IFN-β gene (Muruve and others 2008). Intracellular dsDNA in macrophages also triggers production of IL-1β, which suggests the existence of a DNA-recognizing inflammasome in these cells (Muruve and others 2008; Vilaysane and Muruve 2009). Together, these observations suggest that irrespective of cell type the cytoplasmic DNA elicits a response, which results in production of the type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines.

Inflammasome

It has been shown that a complex of cytoplasmic proteins is rapidly activated after infection (Petrilli and others 2005, 2007; Franchi and others 2009). This protein complex is termed inflammasome. The activation of inflammasome results in the activation of caspase-1, which in turn converts the immature forms of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β and IL-18, to generate the mature forms of these cytokines (Petrilli and others 2007; Franchi and others 2009). These cytokines induce innate immune responses. It has been known for sometime that cytoplasmic DNA can trigger an inflammatory response (Muruve and others 2008; Vilaysane and Muruve 2009). However, proteins acting as DNA sensors in the cytoplasm in the innate immune responses remain to be identified and their roles remain to be elucidated. It has been proposed that a candidate DNA sensor protein in the cytoplasm should have the ability to bind DNA (Bürckstümmer and others 2009). Moreover, expression of the candidate sensor protein should be transcriptionally regulated by cytokines as part of a positive (or negative) feedback loop to sustain (or terminate) antimicrobial responses. Based on the above criteria, the p200-family cytoplasmic proteins (cytoplasmic in the absence of any IFN treatment), such as absent in melanoma 2 and p202, are excellent candidates for sensing DNA in cytoplasm: their expression is likely to be regulated by cytokines (including IFNs) in immune cells and these proteins contain OB-folds to sense DNA.

It has been proposed that in response to cytosolic bacteria, type I IFNs act as checkpoint to control inflammasome activation (Henry and others 2007). Cytosolic localization of Francisella tularensis subspecies novicida in macrophages (from C57BL/6 mice) induces a type I IFN response that is essential for caspase-1 activation, inflammation-mediated cell death, and release of IL-1β and IL-18. Moreover, type I IFN response is also necessary for inflammasome activation in response to cytosolic Listeria monocytogenes, but not vacuole-localized Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Henry and others 2007) Although, the IFN-inducible proteins that may be participating in activation of inflammasome following cytoplasmic localization of F. tularensis and L. monocytogenes remain unknown, it is interesting to note that expression of Ifi200-family genes (Ifi203, Ifi204, and Ifi205) is up-regulated in C57BL/6 bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) following infections with Francisella novicida (Henry and others 2007). Therefore, further work will be needed to determine whether increased expression of IFN-inducible p200-family proteins in F. novicida-infected macrophages contributes to the activation of inflammasome and cell death.

AIM2 and p202 proteins as DNA sensors in cytoplasm

In a systematic study, Bürckstümmer and others (2009) demonstrated that Myc-tagged human AIM2 protein, when overexpressed in HeLa cells, is detected primarily in the cytoplasm using antibodies to the tag followed by detection of indirect immunofluorescence. Moreover, the AIM2 protein preferably recognized dsDNA (as compared to ssDNA or RNA). The study also showed that a substitution (F165A) in the 200-AA repeat, which contains 2 consecutive OB-folds, abrogated the binding of AIM2 protein to dsDNA. Based on earlier observation that an inflammasome activator acts through apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), but not NALP3, authors reasoned that the presence of a PYD domain, which is a known homotypic protein interaction domain, in both AIM2 and ASC proteins should allow them to interact with each other. Indeed, their experiments revealed that these 2 proteins can interact with each other and colocalize in cells when overexpressed in HeLa cells. Furthermore, the study provided evidence that a minimal pathway for inflammasome activation in human HEK293 transfected cells requires AIM2, ASC, caspase-1, and IL-1β.

Similarly, 2 other studies (Fernandes-Alnemri and others 2009; Hornung and others 2009) reported that in response to cytoplasmic DNA the AIM2 protein activates inflammasome and cell death. The study by Fernandes-Alnemri and others (2009) showed that in transfected human kidney cells (HEK293 cells) overexpressed tagged AIM2 protein localizes in the cytoplasm, senses cytoplasmic DNA by OB-fold, and interacts with ASC through its PYD domain to activate caspase-1. Authors also noted that only AIM2 among other members of the p200-family protein specifically interacted with ASC to activate caspase-1 and interaction of AIM2 to ASC resulted in cell death in caspase-1-dependent manner. Interestingly, knockdown of AIM2 expression by short-interfering RNA in cells reduced inflammasome activation by cytoplasmic DNA in mouse and human macrophages, whereas stable overexpression of AIM2 protein in the nonresponsive human embryonic kidney 293T cell line resulted in responsiveness of cells to cytoplasmic DNA. Additionally, authors reported that cytoplasmic DNA triggered formation of the AIM2 inflammasome by inducing an oligomerization of the AIM2 protein. Similarly, the study by Hornung and others (2009) reported that, when overexpressed in transfected HEK293 cells, CFP-fused AIM2 protein localized to cytoplasm and associated with adaptor protein ASC to activate both NF-κB and caspase-1. Moreover, knockdown of Aim2 expression in a murine macrophages cell line or primary macrophages abrogated the caspase-1 activation in response to cytoplasmic dsDNA and dsDNA vaccinia virus (Hornung and others 2009).

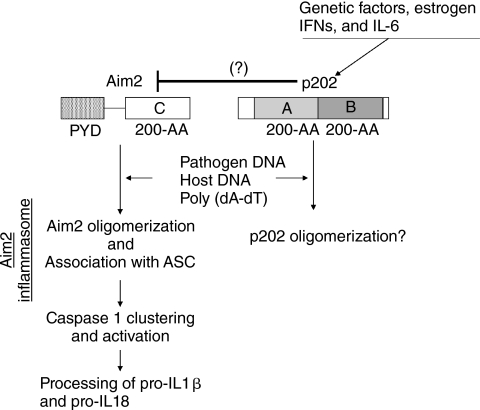

Intriguingly, a report identified the p202 as a dsDNA-binding protein in cytoplasm of BMM (Roberts and others 2009). The study also noted that transfection of siRNA to Ifi202 in BALB/c BMM enhanced the dsDNA-induced activation of caspase-3 and caspase-1 and proposed that heterodimerization of p202 with AIM2 would inhibit the AIM2-mediated activation of caspases and subsequently cell death (Fig. 4). Although their observations are in agreement with other studies that have shown that increased levels of p202 protein in a variety of cells promote cell survival and reduced levels of p202 increase cell death (Choubey and Kotzin 2002; Choubey and Panchanathan 2008), the study did not provide any experimental evidence on the specificity of polyclonal antibodies to the p202 protein(s) that were utilized. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the commercially available polyclonal p202 antibodies that were used by Roberts and others (2009) specifically detected the p202 proteins (p202a, p202b, or both) or other cross-reacting proteins in BMM cytoplasm. Consequently, additional approaches, such as cell fractionation, will be needed to confirm subcellular localization of the p202 protein(s) in BMM cytoplasm.

FIG. 4.

A proposed model for physical and functional interactions between the murine Aim2 and p202 proteins. The model is based on demonstrated preferential binding of the 200-AA repeat in human AIM2 protein, which shares 55.7% amino acid identity with the murine Aim2 protein, with dsDNA (synthetic, pathogen- or host-derived) and the pyrin domain-dependent recruitment of the ASC adaptor protein that resulted in the formation of AIM2 inflammasome (Schroder and others 2009; Krieg 2009). The AIM2 inflammasome activated caspase-1, which promoted the processing of proinflammatory cytokines, such as pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18. The AIM2 protein can bind to p202 (Choubey and others 2000) and the p202 protein can form homodimers (Koul and others 1998). Therefore, it has been proposed (Roberts and others 2009; Krieg 2009) that increased levels of the p202 protein, which depend on the promoter polymorphisms in the Ifi202 gene, levels of cytokines (eg, IFNs and IL-6), and the female sex hormone estrogen (Choubey and Panchanathan 2008) in immune cells inhibit the formation of the Aim2 inflammasome.

p202 as a potential negative regulator of the AIM2 inflammasome

Promoter polymorphisms-dependent increased expression of the Ifi202 in certain strains of female mice is associated with increased susceptibility to develop lupus-like disease (Rozzo and others 2001; Choubey and Kotzin 2002; Choubey and Panchanathan 2008). Moreover, this phenotype is associated with defects in apoptosis of splenic B cells and inhibition of the expression of proapoptotic genes whose expression is regulated by p53 (Xin and others 2006) or E2F1 (Panchanathan and others 2008) in immune cells. Interestingly, p202 protein, which lacks a PYD domain, can also sense foreign or self-DNA in cytoplasm (Roberts and others 2009) and has the ability to heterodimerize with the AIM2 protein in vitro (Choubey and others 2000). Therefore, heterodimerization of p202 with Aim2 in cytoplasm is predicted to inhibit Aim2-induced clustering of the adopter protein ASC and caspase activation (Fig. 4; Roberts and others 2009). Notably, levels of the p202 protein vary greatly between certain lupus-prone and non-lupus-prone strains of mice: higher in certain lupus-prone strains, such as NZB and (NZB × NZW)F1 than non-lupus-prone strains, such as C57BL/6 (Rozzo and others 2001; Choubey and Panchanathan 2008). Furthermore, subcellular localization of the p202 protein is regulated by the type I IFN (Choubey and Lengyel 1993; Choubey and others 2003). Therefore, further work is needed to determine whether the ratio between the p202 and Aim2 proteins in immune cells varies among different strains of mice and whether the ratio between the 2 proteins in the cytoplasm determines cellular responses after sensing the cytoplasmic DNA.

The p200-family proteins and NF-κB

Increased expression of p202 in cell lines inhibits transcriptional activity of NF-κB (Min and others 1996; Wen and others 2000; Ma and others 2003). The p202 inhibits transcriptional activation of the NF-κB target genes by inhibiting the specific DNA-binding activity of the p65/p50 heterodimer and p65 homodimer and by potentiating the specific DNA-binding activity of the p50 homodimer, a transcriptional repressor (Min and others 1996; Ma and others 2003). In contrast, increased expression of p202 in (NZB × NZW)F1 dendritic cells stimulated the NF-κB-mediated transcription of target genes (Yamaguchi and others 2007). Therefore, these studies suggest that p202 may modulate the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in cell type-dependent manner.

Transfection of human breast cancer cell lines with a plasmid encoding the human AIM2 protein along with the NF-κB-luc reporter plasmid is reported to suppress the transcriptional activity of NF-κB (Chen and others 2006). Moreover, transfection of human HEK293-ASC-YEF cell line with increasing amounts of a plasmid encoding human AIM2 protein along with the NF-κB-luc reporter plasmid is reported to stimulate the activity of the reporter (Hornung and others 2009). However, it remains to be determined how increased levels of the AIM2 protein modulate the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in immune cells. Moreover, it remains to be determined whether the murine Aim2 also modulates the transcriptional activity of NF-κB.

As stated above, p202 and the human AIM2 proteins can heterodimerize (Choubey and others 2000). In light of their ability to heterodimerize, the above observations that increased levels of p202 and AIM2 proteins can modulate the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in a variety of transfected cells, it will be important to investigate whether alterations in the expression of p202 (or possibly other p200-family proteins) and Aim2 proteins in immune cells, which result in a change in the ratio of these 2 proteins, contribute to the modulation of the transcriptional activity of NF-κB. Inhibition or stimulation of the transcriptional activity of NF-κB by the 2 p200-family proteins is likely to have profound effects on the innate immune responses and autoimmunity (Kopp and Ghosh 1995).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Recent studies (Bürckstümmer and others 2009; Fernandes-Alnemri and others 2009; Hornung and others 2009; Roberts and others 2009), which involved forced overexpression of the mouse and human p200-family proteins in various cell lines and their immunodetection by indirect immunofluorescence, have provided support for the idea that the p200-family proteins, such as absent in melanoma 2 and p202, can sense DNA in cytoplasm. Therefore, these observations suggest a broader role for these p200-family proteins in the regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses. The ability of the absent in melanoma 2 protein to assemble an inflammasome upon sensing DNA raises the possibility that the AIM2 inflammasome might be dysregulated in autoimmune diseases, such as SLE. Indeed, in SLE patients, the active disease is associated with elevated serum levels of type I IFNs and IL-1β (Marshak-Rothstein 2006; Baccala and others 2007, 2009). However, much remains to be determined. Which isoforms of the human and mouse absent in melanoma 2 proteins are predominantly expressed in immune cells and may have access to DNA in cytoplasm? Which signaling pathways regulate the expression of human and mouse absent in melanoma 2 gene? Does IFN signaling regulate subcellular localization of human and/or mouse absent in melanoma 2 protein? Does the murine Aim2 protein heterodimerize with the p202 protein, a proposed negative regulator of the Aim2, in immune cells? Does the ratio between p202 and the Aim2 proteins in cells regulate the activity of the Aim2 inflammasome and, hence, the transcriptional activity of NF-κB following DNA-sensing? Do promoter polymorphisms contribute to differential expression of the mouse Aim2 gene among certain strains of mice? Is the expression of Aim2 gene gender-dependent? Answers to these important questions are likely to improve our understanding how abnormal or excessive detection of nucleic acids by immune cells contributes to chronic inflammation and numerous autoimmune disorders. Moreover, answers to the above questions will also increase our understanding of the functions of the p200-family proteins in innate and adaptive immune responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank past members of the Choubey laboratory and collaborators for their contributions to the p200-family protein research. We also thank Dr. Peter Lengyel for his thoughts and comments on the subject. The research work on p200-family proteins has been supported by grant awards from the National Institutes of Health (AI066261 and AG025036) and Merit Awards from the Department of Veterans Affairs to D.C.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Albrecht M. Choubey D. Lengauer T. The HIN domain of IFI-200 proteins consists of two OB folds. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327(3):679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L. Dixit VM. Koonin EV. Apoptotic molecular machinery: vastly increased complexity in vertebrates revealed by genome comparisons. Science. 2001;291(5507):1279–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5507.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asefa B. Klarmann KD. Copeland NG. Gilbert DJ. Jenkins NA. Keller JR. The interferon-inducible p200 family of proteins: a perspective on their roles in cell cycle regulation and differentiation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;32(1):155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccala R. Gonzalez-Quintial R. Lawson BR. Stern ME. Kono DH. Beutler B. Theofilopoulos AN. Sensors of the innate immune system: their mode of action. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5(8):448–456. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccala R. Hoebe K. Kono DH. Beutler B. Theofilopoulos AN. TLR-dependent and TLR-independent pathways of type I interferon induction in systemic autoimmunity. Nat Med. 2007;13(5):543–551. doi: 10.1038/nm1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baechler EC. Gregersen PK. Behrens TW. The emerging role of interferon in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(6):801–807. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J. Pascual V. Type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Immunity. 2006;25(3):383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J. Pascual V. Palucka AK. Autoimmunity through cytokine-induced dendritic cell activation. Immunity. 2004;20(5):539–550. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochkarev A. Bochkareva E. From RPA to BRCA2: lessons from single-stranded DNA binding by the OB-fold. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland S. Garcia-Sastre A. Vicious circle: systemic autoreactivity in Ro52/TRIM21-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2009;206(8):1647–1651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürckstümmer T. Baumann C. Blüml S. Dixit E. Dürnberger G. Jahn H. Planyavsky M. Bilban M. Colinge J. Bennett KL. Superti-Furga G. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(3):266–272. doi: 10.1038/ni.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen IF. Ou-Yang F. Hung JY. Liu JC. Wang H. Wang SC. Hou MF. Hortobagyi GN. Hung MC. AIM2 suppresses human breast cancer cell proliferation in vitro and mammary tumor growth in a mouse model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(1):1–7. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D. P202: an interferon-inducible negative regulator of cell growth. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2000;14(3):187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D. Comment on: The candidate lupus susceptibility gene Ifi202a is largely dispensable for B-cell function. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(4):558–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken018. author reply 559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D. Gutterman JU. The interferon-inducible growth-inhibitory p202 protein: DNA binding properties and identification of a DNA binding domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;221(2):396–401. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D. Kotzin BL. Interferon-inducible p202 in the susceptibility to systemic lupus. Front Biosci. 2002;7:e252–e262. doi: 10.2741/A921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D. Lengyel P. Interferon action: cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of the interferon-inducible 52-kD protein that is encoded by the Ifi200 gene from the gene 200 cluster. J Interferon Res. 1993;13(1):43–52. doi: 10.1089/jir.1993.13.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D. Panchanathan R. Interferon-inducible Ifi200-family genes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Lett. 2008;119(1-2):32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D. Pramanik R. Xin H. Subcellular localization and mechanisms of nucleocytoplasmic distribution of p202, an interferon-inducible candidate for lupus susceptibility. FEBS Lett. 2003;553(3):245–249. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey D. Walter S. Geng Y. Xin H. Cytoplasmic localization of the interferon-inducible protein that is encoded by the AIM2 (absent in melanoma) gene from the 200-gene family. FEBS Lett. 2000;474(1):38–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell KS. Clarke CJ. Jackson JT. Darcy PK. Trapani JA. Johnstone RW. Biochemical and growth regulatory activities of the HIN-200 family member and putative tumor suppressor protein, AIM2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326(2):417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow MK. Wohlgemuth J. Microarray analysis of gene expression in lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5(6):279–287. doi: 10.1186/ar1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta B. Li B. Choubey D. Nallur G. Lengyel P. p202, an interferon-inducible modulator of transcription, inhibits transcriptional activation by the p53 tumor suppressor protein, and a segment from the p53-binding protein 1 that binds to p202 overcomes this inhibition. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(44):27544–27555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta B. Min W. Burma S. Lengyel P. Increase in p202 expression during skeletal muscle differentiation: inhibition of MyoD protein expression and activity by p202. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(2):1074–1083. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane JA. Bolland S. Nucleic acid-sensing TLRs as modifiers of autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2006;177(10):6573–6578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung KL. Ray ME. Su YA. Anzick SL. Johnstone RW. Trapani JA. Meltzer PS. Trent JM. Cloning a novel member of the human interferon-inducible gene family associated with control of tumorigenicity in a model of human melanoma. Oncogene. 1997;15(4):453–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth SC. Flavell RA. Innate instruction of adaptive immunity revisited: the inflammasome. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:92–98. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T. Yu JW. Datta P. Wu J. Alnemri ES. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009;458(7237):509–513. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L. Eigenbrod T. Muñoz-Planillo R. Nuñez G. The inflammasome: a caspase-1-activation platform that regulates immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(3):241–247. doi: 10.1038/ni.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman AL. Tang L. Kulaeva OI. Ye B. Li Q. Nahhas F. Roberts PC. Land SJ. Abrams J. Tainsky MA. Expression profiling identifies three pathways altered in cellular immortalization: interferon, cell cycle, and cytoskeleton. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(9):879–889. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.9.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudo G. Toniato E. Engel DA. Lengyel P. Interferons as gene activators. Characteristics of an interferon-activatable enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(24):11878–11883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubbels MR. Jørgensen TN. Metzger TE. Menze K. Steele H. Flannery SA. Rozzo SJ. Kotzin BL. Effects of MHC and gender on lupus-like autoimmunity in Nba2 congenic mice. J Immunol. 2005;175(9):6190–6196. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa S. Furukawa Y. Li M. Satoh S. Kato T. Watanabe T. Katagiri T. Tsunoda T. Yamaoka Y. Nakamura Y. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression in intestinal-type gastric cancers using a complementary DNA microarray representing 23,040 genes. Cancer Res. 2002;62(23):7012–7017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry T. Brotcke A. Weiss DS. Thompson LJ. Monack DM. Type I interferon signaling is required for activation of the inflammasome during Francisella infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204(5):987–994. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V. Ablasser A. Charrel-Dennis M. Bauernfeind F. Horvath G. Caffrey DR. Latz E. Fitzgerald KA. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 2009;458(7237):514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature07725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii KJ. Coban C. Kato H. Takahashi K. Torii Y. Takeshita F. Ludwig H. Sutter G. Suzuki K. Hemmi H. Sato S. Yamamoto M. Uematsu S. Kawai T. Takeuchi O. Akira S. A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(1):40–48. doi: 10.1038/ni1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway CA., Jr. Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone RW. Trapani JA. Transcription and growth regulatory functions of the HIN-200 family of proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(9):5833–5838. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen TN. Roper E. Thurman JM. Marrack P. Kotzin BL. Type I interferon signaling is involved in the spontaneous development of lupus-like disease in B6.Nba2 and (B6.Nba2 × NZW) F(1) mice. Genes Immun. 2007;8(8):653–662. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanta H. Mohan C. Three checkpoints in lupus development: central tolerance in adaptive immunity, peripheral amplification by innate immunity and end-organ inflammation. Genes Immun. 2009;10(5):390–396. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith MP. Moratz C. Tsokos GC. Anti-RNP immunity: implications for tissue injury and the pathogenesis of connective tissue disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6(4):232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp EB. Ghosh S. NF-kappa B and rel proteins in innate immunity. Adv Immunol. 1995;58:1–27. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koul D. Obeyesekere NU. Gutterman JU. Mills GB. Choubey D. p202 self-associates through a sequence conserved among the members of the 200-family proteins. FEBS Lett. 1998;438(1-2):21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg AM. AIMing 2 detect foreign DNA. Sci Signal. 2009;2(77):pe39. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.277pe39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai Y. Takeuchi O. Akira S. TLR9 as a key receptor for the recognition of DNA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(7):795–804. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolfo S. Gariglio M. Gribaudo G. Lembo D. The Ifi200 genes: an emerging family of IFN-inducible genes. Biochimie. 1998;80(8-9):721–728. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengyel P. Choubey D. Li SJ. Datta B. The interferon-activatable gene 200-cluster: from structure toward function. Semin Virol. 1995;6:203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q. Shen N. Li XM. Chen SL. Genomic view of IFN-alpha response in pre-autoimmune NZB/W and MRL/lpr mice. Genes Immun. 2007;8(7):590–603. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow LE. Johnstone RW. Clarke CJ. The HIN-200 family: more than interferon-inducible genes? Exp Cell Res. 2005;308(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XY. Wang H. Ding B. Zhong H. Ghosh S. Lengyel P. The interferon-inducible p202a protein modulates NF-kappaB activity by inhibiting the binding to DNA of p50/p65 heterodimers and p65 homodimers while enhancing the binding of p50 homodimers. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(25):23008–23019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(11):823–835. doi: 10.1038/nri1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell BB. Vertino PM. TMS1/ASC: the cancer connection. Apoptosis. 2004;9(1):5–18. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000012117.32430.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min W. Ghosh S. Lengyel P. The interferon-inducible p202 protein as a modulator of transcription: inhibition of NF-kappa B, c-Fos, and c-Jun activities. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(1):359–368. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moggs JG. Ashby J. Tinwell H. Lim FL. Moore DJ. Kimber I. Orphanides G. The need to decide if all estrogens are intrinsically similar. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(11):1137–1142. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münz C. Lünemann JD. Getts MT. Miller SD. Antiviral immune responses: triggers of or triggered by autoimmunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(4):246–258. doi: 10.1038/nri2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muruve DA. Pétrilli V. Zaiss AK. White LR. Clark SA. Ross PJ. Parks RJ. Tschopp J. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452(7183):103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai K. Kanehisa M. A knowledge base for predicting protein localization sites in eukaryotic cells. Genomics. 1992;14(4):897–911. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchanathan R. Shen H. Bupp MG. Gould KA. Choubey D. Female and male sex hormones differentially regulate expression of Ifi202, an interferon-inducible lupus susceptibility gene within the Nba2 interval. J Immunol. 2009;183(11):7031–7038. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchanathan R. Xin H. Choubey D. Disruption of mutually negative regulatory feedback loop between interferon-inducible p202 protein and the E2F family of transcription factors in lupus-prone mice. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):5927–5934. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrilli V. Papin S. Tschopp J. The inflammasome. Curr Biol. 2005;15(15):R581. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pétrilli V. Dostert C. Muruve DA. Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a danger sensing complex triggering innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(6):615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(5):375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik R. Jørgensen TN. Xin H. Kotzin BL. Choubey D. Interleukin-6 induces expression of Ifi202, an interferon-inducible candidate gene for lupus susceptibility. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(16):16121–16127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC. Doctor K. Rojas A. Zapata JM. Stehlik C. Fiorentino L. Damiano J. Roth W. Matsuzawa S. Newman R. Takayama S. Marusawa H. Xu F. Salvesen G. Godzik A RIKEN GER Group; GSL Members. Comparative analysis of apoptosis and inflammation genes of mice and humans. Genome Res. 2003;13(6B):1376–1388. doi: 10.1101/gr.1053803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TL. Idris A. Dunn JA. Kelly GM. Burnton CM. Hodgson S. Hardy LL. Garceau V. Sweet MJ. Ross IL. Hume DA. Stacey KJ. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science. 2009;323(5917):1057–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1169841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozzo SJ. Allard JD. Choubey D. Vyse TJ. Izui S. Peltz G. Kotzin BL. Evidence for an interferon-inducible gene, Ifi202, in the susceptibility to systemic lupus. Immunity. 2001;15(3):435–443. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Raber ML. Baccala R. Haraldsson KM. Choubey D. Stewart TA. Kono DH. Theofilopoulos AN. Type-I interferon receptor deficiency reduces lupus-like disease in NZB mice. J Exp Med. 2003;197(6):777–788. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K. Muruve DA. Tschopp J. Innate immunity: cytoplasmic DNA sensing by the AIM2 inflammasome. Curr Biol. 2009;19(6):R262–R265. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen GC. Lengyel P. The interferon system. A bird's eye view of its biochemistry. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(8):5017–5020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR. Williams BRG. Silverman RH. Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons? Ann Rev Biochem. 1999;67:227–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehlik C. Reed JC. The PYRIN connection: novel players in innate immunity and inflammation. J Exp Med. 2004;200(5):551–558. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson DB. Connections between antiviral defense and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(3):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson DB. Medzhitov R. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity. 2006;25(3):373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theofilopoulos AN. Baccala R. Beutler B. Kono DH. Type I interferon (α/β) in immunity and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:307–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaysane A. Muruve DA. The innate immune response to DNA. Semin Immunol. 2009;21(4):208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Chatterjee G. Meyer JJ. Liu CJ. Manunath NA. Bray-Ward P. Lengyel P. Characteristics of three homologous 202 genes (Ifi202a, Ifi202b, and Ifi202c) from the murine interferon-activatable gene 200 cluster. Genomics. 1999;60:281–294. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y. Yan DH. Spohn B. Deng J. Lin SY. Hung MC. Tumor suppression and sensitization to tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis by an interferon-inducible protein, p202, in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ. Jackson SP. The TATA-binding protein: a central role in transcription by RNA polymerases I, II and III. Trends Genet. 1992;8(8):284–288. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerner SM. Kloor M. Schwitalle Y. Youmans H. Doeberitz MK. Gebert J. Dihlmann S. The putative tumor suppressor AIM2 is frequently affected by different genetic alterations in microsatellite unstable colon cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(12):1080–1089. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H. D'Souza S. Jørgensen TN. Vaughan AT. Lengyel P. Kotzin BL. Choubey D. Increased expression of Ifi202, an IFN-activatable gene, in B6.Nba2 lupus susceptible mice inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis. J Immunol. 2006;176(10):5863–5870. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi M. Hashimoto M. Ichiyama K. Yoshida R. Hanada T. Muta T. Komune S. Kobayashi T. Yoshimura A. Ifi202, an IFN-inducible candidate gene for lupus susceptibility in NZB/W F1 mice, is a positive regulator for NF-kappaB activation in dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2007;19(8):935–942. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H. Dalal K. Hon BK. Youkharibache P. Lau D. Pio F. RPA nucleic acid-binding properties of IFI16-HIN200. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784(7-8):1087–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K. Kagan D. DuBois W. Robinson R. Bliskovsky V. Vass WC. Zhang S. Mock BA. Mndal, a new interferon-inducible family member, is highly polymorphic, suppresses cell growth, and may modify plasmacytoma susceptibility. Blood. 2009;114(14):2952–2960. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]