In this study, we utilized genetic and cell biological approaches to evaluate potential functions for the AMPKα C-terminus. We identify a critical new function for the carboxy-terminal amino acids of AMPKα in vivo, which affects AMPKα subcellular localization, phosphorylation, and ultimately organismal viability.

Abstract

The metabolic regulator AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) maintains cellular homeostasis through regulation of proteins involved in energy-producing and -consuming pathways. Although AMPK phosphorylation targets include cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins, the precise mechanisms that regulate AMPK localization, and thus its access to these substrates, are unclear. We identify highly conserved carboxy-terminal hydrophobic amino acids that function as a leptomycin B–sensitive, CRM1-dependent nuclear export sequence (NES) in the AMPK catalytic subunit (AMPKα). When this sequence is modified AMPKα shows increased nuclear localization via a Ran-dependent import pathway. Cytoplasmic localization can be restored by substituting well-defined snurportin-1 or protein kinase A inhibitor (PKIA) CRM1-binding NESs into AMPKα. We demonstrate a functional requirement in vivo for the AMPKα carboxy-terminal NES, as transgenic Drosophila expressing AMPKα lacking this NES fail to rescue lethality of AMPKα null mutant flies and show decreased activation loop phosphorylation under heat-shock stress. Sequestered to the nucleus, this truncated protein shows highly reduced phosphorylation at the key Thr172 activation residue, suggesting that AMPK activation predominantly occurs in the cytoplasm under unstressed conditions. Thus, modulation of CRM1-mediated export of AMPKα via its C-terminal NES provides an additional mechanism for cells to use in the regulation of AMPK activity and localization.

INTRODUCTION

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) consists of a trimer containing a catalytic serine-threonine kinase subunit (α) and two regulatory subunits (β and γ; Davies et al., 1994; Stapleton et al., 1994; Gao et al., 1996). Many cellular stressors activate AMPK, including oxidative stress, heat shock, and low energy levels (low ATP-AMP ratios). In response, AMPK restores energetic balance by inhibiting anabolic processes that consume energy, whereas activating catabolic pathways to conserve energy within the cell (for review Hardie, 2007). As an example, AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits cytoplasmic acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC), a rate-limiting enzyme in energy-consuming fatty acid synthesis (Carling et al., 1987; Davies et al., 1989), with concomitant activation of energy-producing fatty acid oxidation, likely due to activation of carnitine-palmitoyl transferase I (CPT1) by increased malonyl-CoA (Hardie et al., 1998).

For most kinases, distinguishing in vivo from in vitro targets remains a difficult endeavor, as homogenized cells and tissues frequently used for in vitro kinase assays allow proteins that are normally either spatially or temporally separated to come into contact with each other. One means for regulating kinase access to targets in vivo is through such spatiotemporal control of each component. Although AMPK can be found both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Salt et al., 1998), the exact mechanisms regulating its subcellular localization have not been fully elucidated. In yeast, only alkaline pH has been shown to induce movement of SNF1, the AMPKα orthologue in yeast, from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Hong and Carlson, 2007). In mammalian cells, leptin (Suzuki et al., 2007) and heat shock—possibly through MEK signaling (Kodiha et al., 2007)—can also cause translocation of AMPKα subunits to the nucleus. In addition, isoform-specific AMPK subunits have also been shown to accumulate in the nucleus in a circadian manner (Lamia et al., 2009), and nuclear translocation can also be induced in vivo in muscle cells after exercise stress (McGee et al., 2003).

AMPK subcellular localization could have many important functional consequences. The most apparent expected effects of increasing nuclear localization would include an increase in phosphorylation of nuclear substrates of AMPK, such as the peroxisomes proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), whereas cytoplasmic targets such as ACC would show decreased phosphorylation. To add further complexity to AMPK regulation, one of the upstream AMPK activators, the LKB1 kinase, also shuttles in and out of the nucleus (Dorfman and Macara, 2008), but is largely activated in the cytoplasm (Boudeau et al., 2003a).

Primary amino acid sequence analysis can sometimes predict structure–function relationships for domains of a protein. For single subunit proteins, nuclear localization sequences and nuclear export sequences within the protein itself help identify mechanisms for its localization. However, for multisubunit kinases like AMPK and the LKB1/STRAD/MO25 complex, such regulation is more complicated.

Although the AMPKα amino-terminus is highly conserved, containing the serine-threonine kinase domain, the AMPKα carboxy-terminus does not contain any known functional motifs outside of the β/γ binding sites. We previously noted that the final carboxy-terminal 20 amino acids of AMPKα are highly conserved across diverse species (Brenman and Temple, 2007). In this study, we utilized genetic and cell biological approaches to evaluate potential functions for the AMPKα C-terminus. We identify a critical new function for the carboxy-terminal amino acids of AMPKα in vivo, which affects AMPKα subcellular localization, phosphorylation, and ultimately organismal viability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generating Transgenic Flies

Truncated dAMPKαΔC was cloned into a pUAST vector as a BglII-EcoRI fragment of a dAMPKα-RA transcript (www.flybase.org) by inserting a stop codon after Proline 561 of wild-type dAMPKα using PCR-based mutagenesis. The GFP::dAMPKα and mCherry::dAMPKαΔC fusion proteins were made using green fluorescent protein (GFP) or mCherry at the fused in-frame to the N-terminus of dAMPKα in the pUAST vector. Transgenes were introduced into a w1118 stock via P-element–mediated transformation by the Duke Animal Models Core facility.

Fly Stocks and Crosses

UAS-dAMPKα wt and UAS-dAMPKαΔC alleles expressed in sensory neurons using a l(2)109-80-GAL4 driver (Gao et al., 1999) and recombined with UAS-actin::GFP to visualize sensory neurons, as described previously (Medina et al., 2006). For rescue experiments, both constructs were expressed using the Ubiquitin-Gal4 driver and crossed into dampkα3 null mutants. Adult males were scored for rescue by nonbar eye phenotype because of the lack of FM7 balancer chromosome. All flies were maintained at 25°C in yeast-cornmeal vials. Heat-shock experiments were performed by crossing mCherry and GFP constructs of wild-type dAMPKα to Ubiquitin-Gal4. Third instar larvae were subjected to heat shock for 1 h at 37°C and allowed to recover for 15 min at 25°C. Live larval imaging was performed as described (Mirouse et al., 2007) using the 488-nm argon line for GFP and the 543-nm helium neon line for mCherry on a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope (Thornwood, NY). UAS-GFP::APC2 flies were a gift from Dave Roberts and Mark Peifer (UNC-Chapel Hill).

Plasmid Construction

For cell culture studies, both wild-type and truncated versions of AMPKα2 were amplified by PCR using Pfu DNA Polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) from rat AMPKα2 (AddGene, Cambridge, MA; plasmid 15991) and inserted into pEGFP-C1 (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA). Mouse AMPKα1 wild-type and truncated versions were generated using PCR amplification from mouse cDNA and inserted into pEGFP-C1. The SV40-NLS (nuclear localization signal; PKKKRKVG), AMPKα2, and AMPKα1 C-terminal tail tags were cloned into the C-terminus of the pEGFP-C1::GFP construct. For expressing the SV40NLS and the AMPKα2 C-terminal tag together, the SV40NLS coding sequence was inserted into the N-terminal forward primer for amplification of the GFP-coding sequence. The SV40NLS::GFP amplicon was then inserted into a pEGFP-C2 plasmid containing the AMPKα2 C-terminal tail-coding sequence at the C-terminus of that plasmid.

L546A and L550A substitutions in the AMPKα2 C-terminal tail sequence were inserted into the reverse primer sequence and cloned using site-directed mutagenesis. Hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged human AMPKγ1 and rat AMPKβ1 constructs were gifts from Reuben Shaw (UCSD), and mCherry::AMPKγ1 was produced by inserting human AMPKγ1 into a modified pEGFP-N1 vector with GFP replaced by Flag::mCherry (gift from Tom Maynard, UNC-Chapel Hill). Myc-tagged clones of wild-type AMPKα2, AMPKα2ΔC, and AMPKα2L,L-A,A constructs were all generated using standard site-directed mutagenesis and inserted into the pCMV-myc vector (Clontech, 631604). The RanQ69L clone was a gift from Andrew Wilde (University of Toronto), which was then inserted into a pmCherry-C1 plasmid for live cell visualization.

To generate AMPK-CRM1-NES (nuclear export sequence) fusions, sequences encoding residues Met1 to Val14 (human Snurportin-1) or Ser35 to Ile47 (human cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitor alpha [PKIA]) were added after Asp538 of rat AMPKα2, replacing the C-terminal tail. Truncated AMPKα2 missing only the last 14 amino acids (AMPKα2ΔC538) was produced by introducing a UGA stop codon after Asp538. For GFP-tagged constructs, products were amplified using PCR, ligated into the pEGFP-C1 vector and sequenced to verify fidelity. For myc-tagged constructs, the coding regions were amplified from the above GFP-AMPKα2 plasmids and inserted into the pCMV-myc vector.

Immunohistochemistry

AMPKα localization in fly tissue was determined using standard dissection and immunostaining procedures (Medina et al., 2006). The primary antibody was anti-AMPKα (mouse; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; ab51025) and the secondary antibody was Cy-3–conjugated anti-mouse (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). During the wash steps, ToPro-3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to the wash solution and incubated for 30 min to stain nuclei. Larval fillets were mounted on slides in 70% glycerol in 1× PBS. Images were collected by confocal microscopy with a 40× oil immersion lens (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss Microimaging) using suitable GFP, Cy3, and ToPro-3 excitation wavelengths.

AMPKα Immunoprecipitation

Drosophila protein lysates for immunoprecipitation were prepared by collecting equal numbers of male and female flies (50 total) of each genotype in a 1.5-ml tube. One milliliter lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate 1 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, and 1:500 dilution of Sigma (St. Louis, MO) mammalian protease inhibitor cocktail) was added to each sample. Flies were then ground to homogeneity with a pestle, sonicated, and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove insoluble material and debris. Supernatants were collected, and the protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad Dc protein assay (Richmond, CA). Immune complexes were formed by incubation of 100 μl of anti-dAMPKα mouse mAb (Abcam; ab51025) with 1 ml of 1 mg/ml fly lysate overnight at 4°C. Antibodies were precipitated by incubation with 20 μl protein A/G agarose (Pierce Protein Research Products, Rockford, IL) for 3 h, followed by centrifugation and washing with lysis buffer. Proteins were eluted by 10-min incubation at 70°C in LDS-loading buffer (Invitrogen) and separated on 4–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels along with 50 μg of crude lysates. Electrophoresis was followed by Western blotting and probing for phospho-AMPKα (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA; 2535) and total dAMPKα, with anti-lamin C (LC28.26, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) used as a loading control.

AMPKα/β/γ Coimmunoprecipitation

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with myc-tagged AMPKα2, HA-tagged AMPKβ1, and FLAG-tagged Cherry-AMPKγ1 in 10-cm dishes. Cells were harvested and lysed in 0.5 ml lysis buffer (see above), sonicated, and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations of supernatants were determined followed by overnight incubation of 1 ml of each lysate at 1 mg/ml with 100 μl of anti-myc antibody (9E 10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Antibody precipitation and blotting were performed as described above. Primary antibody dilutions were anti-Myc (1:100), anti-HA (1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, F-7), and anti-FLAG (1:1000, Sigma, M2). All blots were scanned and quantified using the Odyssey Infrared System (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) using fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies (Li-Cor; IRDye 680 anti-rabbit IgG and IRDye 800 anti-mouse IgG).

Cell Culture and Treatments

HEK293, HeLa, and CHO cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were plated 24 h before transfection. DNA transfection of cells (1 μg of DNA to 2 ml of medium) was performed using PolyJet DNA Transfection Reagent (SignaGen Laboratories, Ijamsville, MA), as directed by the supplier. LMB (10 ng/ml, Sigma) and cycloheximide (1 μg/ml, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) were premixed in culture medium and added as indicated. Cells were treated with cycloheximide for 1 h before addition of leptomycin B (LMB) mix for indicated times.

Nuclear Localization Assay, Live Cell Imaging, and Tiling

HEK293 cells were transfected with the constructs indicated and scored 24 h later using fluorescence microscopy to observe the subcellular localization of GFP. 2xGFP alone was the negative control for localization and for treatment with LMB. For each GFP fusion, 200 cells were counted and scored as follows: predominantly nuclear, nuclear and cytoplasmic, or predominantly cytoplasmic localization. For imaging, cells were fixed and stained with DRAQ-5 (Biostatus Limited, Shepshed, Leicestershire, United Kingdom) to visualize nuclei. For live cell imaging, 24 h after transfection the cells were treated with cycloheximide (1 μg/ml) for 1 h followed by treatment with LMB (10 ng/ml). Pictures were taken every 10 min for GFP localization using an Olympus FV100 microscope (Melville, NY). Tiling images were also taken using the Olympus FV100 multiarea time-lapse imaging program followed by counting and deciphering of the subcellular localization of GFP as previously described (Henderson, 2000). To control for biased counting, 50 cells from each of the three classes (N, NC, and C) were selected and the fluorescence intensities were quantified as previously described (Henderson, 2000). For cells identified as predominantly nuclear, the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic GFP level in a cell was greater than 2, for nuclear and cytoplasmic localization the same ratio was between 0.7 and 2, and for predominantly cytoplasmic localization the ratio was below 0.7.

RESULTS

The AMPKα Carboxy-Terminus Is Required for Function

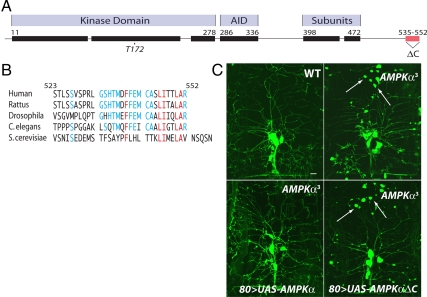

Despite containing a highly conserved carboxy-terminus (Brenman and Temple, 2007; Figure, 1, A and B), the AMPKα C-terminal 23 amino acids do not contain predicted functional motifs. Cocrystal structures of the carboxy-terminus of AMPKα with β/γ subunits indicate that the carboxy-tail participates in intermolecular interactions with the β subunit and intramolecular interactions with the rest of the C-terminal domain (Amodeo et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2007), although previous studies also suggest that the AMPKα carboxy-tail is not required for association with the β/γ subunits (Iseli et al., 2005).

To test the functional significance of the AMPKα carboxy-terminus, we generated transgenic Drosophila expressing full-length AMPKα lacking the final 22 amino acids (AMPKαΔC) for reintroduction into AMPKα mutant or wild-type backgrounds. Although vertebrates contain two largely genetically redundant AMPKα genes, Drosophila encodes only a single AMPKα gene, thus greatly simplifying in vivo genetic analyses. Expression of full-length (amino terminally tagged or untagged) versions of AMPKα in a null background rescues the previously identified neuronal phenotype (Mirouse et al., 2007; Figure 1C), whereas AMPKαΔC versions do not (Figure 1C). Further, although both N-terminally GFP- or mCherry-tagged AMPKα rescue lethal null mutations to full viability at expected Mendelian ratios (data not shown), neither untagged nor tagged AMPKαΔC rescue any mutant alleles to viability (scoring more than 1000 potential rescue events). These experiments indicate a crucial function for the carboxy-terminal 22 amino acids of Drosophila AMPKα in neuronal maintenance and viability.

Figure 1.

AMPKα contains a highly conserved carboxy-terminal tail required for function in vivo. (A) Schematic of AMPKα homology with blocks highlighting regions with >50% conservation among bilateria (rat AMPKα2 as template; calculated by ProPhylER). Amino acid numbers denote the ranges. AID, autoinihibitory domain; 398–472, previously mapped site for β and γ subunit binding. (B) The carboxy-terminal tail sequence alignment of AMPKα orthologues with conserved residues highlighted in blue and invariant residues in red (AMPKα2 for species with multiple AMPKα subunits). (C) Peripheral neurons visualized by Gal4 109(2)80-driven expression of UAS-actin::GFP in wild-type (WT) Drosophila 2nd instar larvae, AMPKα loss of function (AMPKα3) larvae, AMPKα3 expressing a WT AMPKα transgene (80>UAS-AMPKα), or AMPKα3 expressing a C-terminally truncated AMPKα transgene (80>UAS-AMPKα ΔC). Dendritic swellings are highlighted with arrows. Bar, 10 μm.

The Carboxy-Terminal 22 Amino Acids of AMPKα Are Required for Normal Localization In Vivo

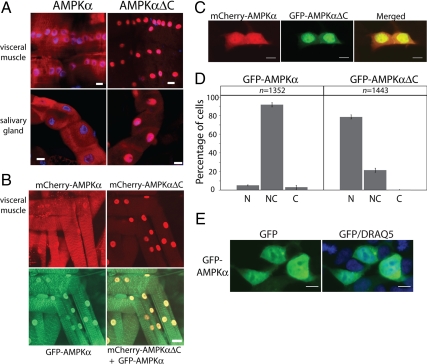

To explore why a 22-amino acid carboxy-terminal deletion of AMPKα fails to rescue AMPKα null mutants, we examined the localization of the truncated protein both by antibody immunohistochemistry and visualization of fluorescently tagged fusion protein. Expression of untagged AMPKα in transgenic animals and subsequent detection of AMPKα by immunohistochemistry revealed very clear subcellular localization differences between full-length and truncated protein (AMPKαΔC; Figure 2A). AMPKαΔC localizes predominantly in the nucleus, whereas full-length protein is both cytoplasmic and nuclear, using either immunohistochemistry of untagged protein (Figure 2A) or live animal images with fluorescently tagged proteins (Figure 2B). The observation that AMPKαΔC is highly enriched in the nucleus was observed in diverse tissues including neurons, muscle, fat bodies, and salivary glands (Figure 2 and data not shown). Differential subcellular localization of AMPKα with and without the carboxy-terminus is most clearly demonstrated using a live transgenic animal simultaneously expressing both full-length and AMPKαΔC in the same cells (Figure 2B). This observation was not restricted to Drosophila in vivo, as a conceptually similar result was observed in transiently transfected mammalian cells (HEK293) in vitro (Figure 2, C and E). Counting of transfected mammalian cells for subcellular localization demonstrated a clear difference between full-length AMPKα and AMPKαΔC (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

AMPKα lacking the carboxy-terminus localizes predominantly to nuclei in vivo and in vitro. (A) Indirect immunofluorescence of AMPKα (red) staining with anti-dAMPKα antibody on transgenic Drosophila 3rd instar larvae expressing either full-length wild-type AMPKα or the carboxy-truncated AMPKα (AMPKαΔC). All transgenic proteins are expressed using the Gal4-UAS system, driven by Ubiquitin-Gal4 (A and B). Nuclei were stained with ToPro-3 (blue). (B) Live animal images of larvae expressing amino-terminal mCherry-tagged wild-type (mCherry-AMPKα) or truncated (mCherry-AMPKαΔC) AMPKα, GFP-tagged wild-type α (GFP-AMPKα) alone or in combination with mCherry-tagged truncated α (mCherry-AMPKαΔC+GFP-AMPKα). Bar, 10 μm. (C) Coexpression of amino-terminal fluorescently tagged full-length AMPKα2 (mCherry-AMPKα, red) and truncated (GFP-AMPKαΔC, green) in the same cotransfected mammalian cells (HEK293). (D) Scoring of transfected cells for subcellular localization of GFP-tagged full-length (GFP-AMPKα) or truncated (GFP-AMPKαΔC) AMPKα as primarily nuclear (N), both nuclear and cytoplasmic (NC), or primarily cytoplasmic (C). Proper scoring for each group was confirmed by quantification of nuclear and cytoplasmic fluorescence for >50 cells in each group; N-C fluorescence ratios were >2.0, 0.7–2.0, and <0.7, for N, NC, and C, respectively. (E) Wild-type GFP-AMPKα control cells demonstrating roughly equal fluorescence in cytoplasm and nucleus. Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Bar, 10 μm.

The AMPKα Carboxy-Tail Functions as a LMB-sensitive NES

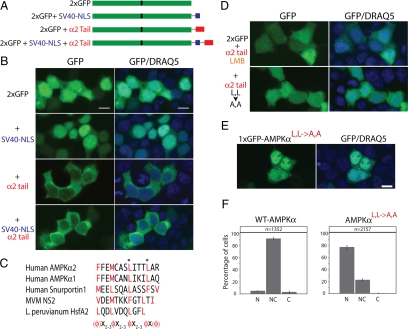

To elucidate whether the carboxy-terminus might act as a NES in AMPKα localization, we used a previously described mammalian cell assay to test for sequences that alter the subcellular localization of proteins (Frederick et al., 2008). We fused the AMPKα carboxy-tail in frame at the C-terminus of two tandem GFP molecules (Figure 3A). Two consecutive fused GFPs (2xGFP, ∼54 kDa) localize diffusely within the nucleus and the cytoplasm, as previously reported by Frederick et al. (2008) (see Figure 3B). Adding the 23-amino acid carboxy tail of rat AMPKα2 (2xGFP-α2 tail) leads to localization predominantly in the cytoplasm (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The carboxy-terminal tail of AMPKα functions as an NES. (A) Schematic representation of the four constructs containing two tandem GFP molecules (2xGFP) with or without the carboxy-terminal 23 amino acids of AMPKα2 (red) and/or the SV40 NLS (blue) used in B. (B) HEK293 cells transfected with constructs containing 2xGFP alone, 2xGFP with the SV40-NLS, 2xGFP with the AMPKα2 tail, or 2xGFP with both the SV40 NLS and the α2 tail. Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5 (blue). (C) Alignment of the AMPKα2/AMPKα1 tail with confirmed CRM1-dependent NESs. The CRM1-NES consensus sequence is shown, consisting of either four or five bulky hydrophobic amino acids (ϕ, red) with variable spacing between them. Key leucine residues (often enriched in CRM1 NES sequences), L546 and L550, that were mutated for D are highlighted with asterisks (*). (D) Cells expressing either 2xGFP fused to the wild-type α2 tail and treated with the CRM1-specific inhibitor leptomycin B (LMB), or 2xGFP with L546A and L550A (L,L→A,A) mutations in the α2 tail, to block CRM1-mediated nuclear export (compare to α2 tail in B). (E) Cells transfected with a GFP-tagged full-length AMPKα2L,L→A,A mutant. (F) Scoring of cells for subcellular localization of GFP-AMPKα with the L,L→A,A mutations to nucleus (N), nucleus and cytoplasm (NC) or cytoplasm (C; as in Figure 2D). Bar, 10 μm.

Because a previous study demonstrated that endogenous (untagged) AMPKα protein in HeLa cells enriches in the nucleus upon treatment with LMB (Kodiha et al., 2007), a specific inhibitor of CRM1-mediated nuclear export (Kutay and Guttinger, 2005), we tested whether LMB specifically inhibits this AMPKα tail-dependent nuclear export. Indeed, LMB treatment does result in altered localization of the 2xGFP-α2 tail from predominantly cytoplasmic (Figure 3B) to both nucleus and cytoplasm (Figure 3D). This effect of LMB can also be illustrated using time-lapse experiments, showing accumulation of proteins containing the carboxy tail of AMPKα2 in the nucleus within 10 min of LMB addition (Supplementary Figure 1).

Because CRM1 NESs are often leucine-rich (Kutay and Guttinger, 2005), we specifically mutated two conserved leucines in the carboxy tail (2xGFP-α2L,L→A,A; Figure 3D), which altered localization to both nuclei and cytoplasm similar to treatment of 2xGFP-α2 tail with LMB. Identical results were obtained using the carboxy tail of AMPKα1 (data not shown), which also contains the same conserved bulky hydrophobic residues (including leucines) at the same positions and suggests that any difference between AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 localization is not due to their tail sequences. Using a larger GFP-tagged construct containing full-length AMPKα with the dual leucine mutations (GFP-AMPKαL,L→A,A) resulted in even more pronounced accumulation in the nucleus (Figure 3, E and F), perhaps because of diminished nondirectional diffusion through the nuclear pore or the presence of nuclear import signals elsewhere on AMPK.

Addition of the carboxy-terminal tail of AMPKα2–2xGFP was even sufficient to overcome nuclear targeting via the SV40 NLS (SV40-NLS α2 tail, Figure 3B). This effect was not due to inactivation of the SV40 NLS, because treatment with LMB induced accumulation of the NLS-containing protein in the nucleus (Supplementary Figure 1). As the tail appears to act as a CRM1-dependent NES, we compared the AMPKα tail sequence to known CRM1-dependent NESs (Figure 3C). Although the precise positioning of key residues for CRM1-dependent NESs vary, they are generally highly enriched for bulky hydrophobic amino acids (ϕ = leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, valine, and methionine) at specified spacings (ϕ-x-2/3-ϕ-x-2/3-ϕ-x-ϕ; Kutay and Guttinger, 2005), generally consistent with an α helix. AMPKα carboxy tails are also enriched for bulky hydrophobic amino acids (Figure 1B), only one residue away from being a canonical NES (Figure 3C). (Yeast SNF1 does indeed match the consensus NES.) However, other proteins with defined NESs, including the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling heat-stress protein, HsfA2, also vary from the canonical consensus containing either four or five bulky hydrophobic residues at more flexible spacings (Heerklotz et al., 2001). According to these more flexible criteria, AMPKα proteins in animals may also match the CRM1 consensus sequence.

AMPKα carboxy-termini contain other conserved residues, including a conserved cysteine and threonine (Figure 1B), suggesting that these residues may be modified in vivo to alter either AMPK activity or localization. In Drosophila, mutating the carboxy tail Cys573 to serine rescued both the neuronal phenotype and lethality of AMPKα null mutants (data not shown), indicating that this cysteine is not essential. Further, in mammalian cells, mutating Thr536 to either a phosphomimetic (aspartate) residue or to an alanine failed to affect the localization of the 2xGFP-α2 tail protein compared with the wild-type tail (data not shown). Therefore we focused our further investigation on the conserved bulky hydrophobic amino acids in the carboxy-terminus as functionally important for the AMPK NES.

AMPKα Cytoplasmic Localization Can Be Restored Using Other Defined NESs

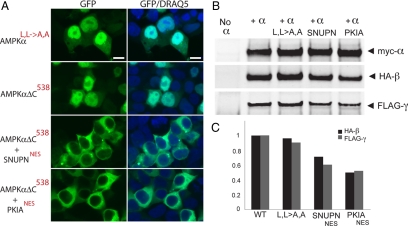

Having identified sequences required for NES function at the carboxy-terminus of AMPKα, we wondered whether other well-documented NESs would function in lieu of the AMPKα carboxy-tail sequence. First, we further refined the putative AMPKα NES to within the carboxy-terminal 14 amino acids based on sequence alignment with other previously characterized CRM1-dependent NESs (Figure 3C) and confirmed the functional consequences of truncating only the final 14 amino acids (AMPKαΔC538), because this shorter truncation also localizes to the nucleus (Figure 4A). We then chose two well-characterized NESs to replace the putative AMPKα NES; there is a crystal structure of snurportin-1 (SNUPN) bound to CRM1 (Dong et al., 2009), whereas PKIA contains a distinct but also well-characterized NES (Fornerod et al., 1997). Both NESs served to restore the AMPKαΔC538 fusion protein to the cytoplasm (Figure 4A). The transplanted NESs did not act by disrupting nuclear import, as both constructs showed increased nuclear localization in the presence of LMB (data not shown). Additionally, the SNUPN-NES and PKIA-NES AMPKα chimeric constructs retain significant affinity for β and γ by coimmunoprecipitation (Figure 4B), despite having no sequence identity with the AMPKα tail, indicating that these localization changes are not due to disruption of the AMPK heterotrimer.

Figure 4.

Previously identified NESs can substitute for the carboxy-terminus of AMPKα to restore cytoplasmic localization. (A) HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with GFP-tagged AMPKα2 constructs containing the L546A and L550A mutations (AMPKαL,L→A,A), a 14-amino acid C-terminal deletion (AMPKαΔC538), or with the 14 C-terminal residues of AMPKα2 replaced with the CRM1-dependent NESs from human snurportin-1 (SNUPN, MEELSQALASSFSV, 14 amino acids) or cyclic-AMP–dependent protein kinase inhibitor α (PKIA, SNELALKLAGLDI, 13 amino acids). Bar, 10 μm. (B) AMPKα, β, and γ subunits were coimmunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibody from HEK cell lysates either expressing HA-tagged AMPKβ1 and FLAG-tagged AMPKγ1 alone (first lane), or coexpressed with myc-tagged wild-type AMPKα, L546A/L550A (L,L→A,A) AMPKα, or SNUPN and PKIA AMPKα-NES chimeras. (C) The relative association of β and γ subunits with myc-tagged wild-type, L,L→A,A mutant, or NES chimera AMPKα variants normalized to AMPKα wild-type levels (WT), calculated from the protein band intensities in B.

As further confirmation that AMPK α/β/γ binding is not responsible for these α-tail–mediated changes in localization, we found that the construct which most strongly abolishes AMPKα cytoplasmic localization (AMPKαL,L→A,A), contains the fewest amino acid changes, and retains essentially wild-type binding to the β and γ subunits (Figure 4B).

The Carboxy-Terminal AMPKα Tail Is Not Required for Binding β/γ Subunits

Although the carboxy tail of AMPKα appears to act as a NES, previous immunoprecipitation experiments with transfected cells mapped the β-binding site to amino acids 313–473 of AMPKα (Iseli et al., 2005), indicating that the carboxy tail of AMPKα is not required for association with the β/γ subunits. The AMPK heterotrimer crystal structures also indicate that the γ subunit has minimal contact with the carboxy tail of AMPKα/SNF1 (Amodeo et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2007). Using coimmunoprecipitation experiments, we also confirmed that the carboxy tail is not required for AMPKα/β/γ association in transfected cells, as β and γ both still associate with AMPKαΔC (Supplementary Figure 2). However, the tail may increase complex association, affinity and/or stability (Iseli et al., 2005 and Supplementary Figure 2).

AMPKα Nuclear Entry Is Dependent on Ran

As the AMPK trimer complex is too large to passively diffuse into the nucleus, we sought to clarify the mechanism of its active transport. Although many proteins are imported into the nucleus through Ran-dependent binding to members of the importin (Imp) family (Strom and Weis, 2001; for review Weis, 2003), proteins may also be translocated through Ran-independent pathways, such as through direct binding to the nuclear pore complex (Matsubayashi et al., 2001).

Several signaling proteins, including ERK2 and MEK1, have a conserved sequence motif (TPT or SPS), in which phosphorylation of these residues will induce translocation into the nucleus in a Ran-independent manner (Chuderland et al., 2008). Although the AMPKα isoforms contain similar sequences (TPS in α1 and TPT in α2), mutation of these residues to alanine or phosphomimetic glutamic acid residues failed to affect the localization of the truncated form of AMPKα (data not shown).

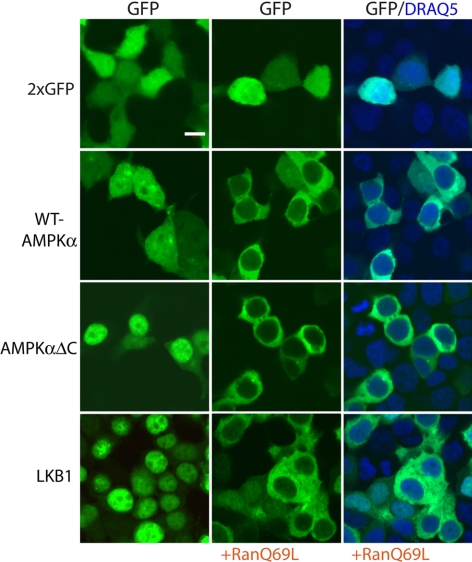

To further distinguish between the possible import pathways responsible for AMPK translocation, we examined the effect of a Ran mutant (RanQ69L) that halts Ran-dependent nuclear import and export by blocking its GTP hydrolysis (Bischoff et al., 1994). Transiently transfecting cells with this Ran mutant along with GFP-tagged AMPKα, we see that AMPKα is restricted to the cytoplasm (2nd row, Figure 5), as is its upstream activator LKB1 (Dorfman and Macara, 2008; 4th row, Figure 5). Even the carboxy-terminal AMPKα truncation (AMPKαΔC), which is normally strongly nuclear, localizes similarly to full-length AMPKα in the presence of RanQ69L (3rd row, Figure 5), indicating that AMPKα is normally basally imported via a Ran-GDP–dependent pathway.

Figure 5.

AMPKα, like LKB1, requires Ran-GTP hydrolysis for nuclear import. HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with constructs expressing two fused GFP molecules (2xGFP), GFP-tagged full-length AMPKα2, truncated AMPKα2 (AMPKαΔC) or LKB1, with or without the GTP-hydrolysis defective Ran mutant RanQ69L. Nuclei are stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Bar, 10 μm.

Conventional NLSs are typically enriched for a single cluster of basic amino acids (K/R; e.g., SV40 NLS) or are separated in a bipartite manner by a linker region of 10–12 residues (Leung et al., 2003). AMPKα2 but not AMPKα1 has been proposed to contain a K-K/R-x-K/R NLS within the kinase domain that is activated by leptin in C2C12 cells (Suzuki et al., 2007), allowing differential localization between AMPKα1 and AMPKα2. Although it is not known whether HEK cells respond to leptin, we did not observe any difference in localization between AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 with or without mutations in this putative kinase domain NLS (data not shown), indicating that this leptin-stimulated nuclear translocation does not function in HEK cells. Along with our findings using RanQ69L and the nuclear localization of the truncated AMPKα in several cell types in Drosophila, these results ultimately suggest that AMPK contains another Ran-dependent NLS, either elsewhere in α, or in the β or γ subunits that is basally active.

We also found that the phosphorylation state of the truncated AMPKα does not affect its nuclear translocation, as HEK cells transfected with C-terminally truncated AMPKα constructs containing T172D and T172A mutations in the activation loop localized similarly to truncated AMPKα (data not shown).

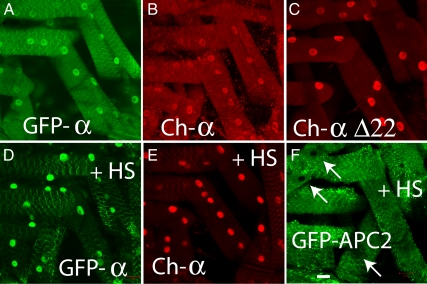

Heat Shock Increases Nuclear AMPKα In Vivo

Numerous in vitro studies have suggested changing cellular environments and conditions may change AMPKα localization, including alkaline pH, heat shock and oxidative stress, and leptin stimulation (Hong and Carlson, 2007; Kodiha et al., 2007; Suzuki et al., 2007). We wondered whether these stressors that affect AMPKα localization in vitro, might also affect AMPKα localization in vivo. Indeed, using live transgenic animal (larvae) imaging, we found that heat-shock induced nuclear enrichment of AMPKα in vivo (Figure 6). Although both GFP- and mCherry-tagged AMPKα increased nuclear enrichment upon heat shock (Figure 6, D and E), other GFP-tagged proteins, including APC2, which contains both NES (Rosin-Arbesfeld et al., 2000) and NLS (Zhang et al., 2000) sequences, did not localize to the nucleus under heat shock (Figure 6F). AMPKα without the carboxy-terminal NES did not appear to change localization significantly (data not shown) because it already appears nuclear (Figure 6C). Other stressors, including inducing oxidative stress by feeding larvae paraquat and food starvation, did not alter AMPKα localization as they had in vitro (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Heat-shocked transgenic larvae demonstrate increased nuclear localization of AMPKα in vivo. Live animal images of 3rd instar Drosophila larvae expressing GFP-tagged (A and D) or mCherry-tagged wild-type AMPKα (B and E), mCherry-tagged truncated AMPKαΔC (C), or GFP-tagged APC2 (containing both NLS and NES sequences). Animals in D–F were subjected to heat shock at 37°C for 1 h, followed by a 15-min recovery at 25°C. All transgenic proteins are expressed using the Gal4-UAS system, driven by Ubiquitin-Gal4. Bar, 20 μm.

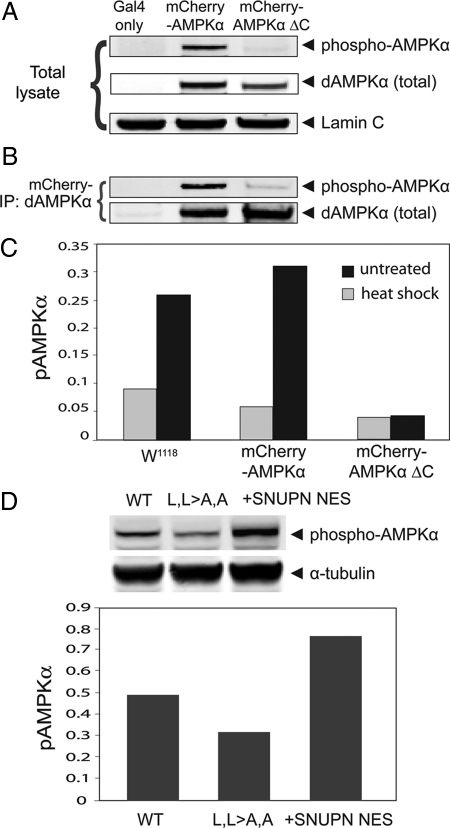

The Truncated Nuclear AMPKα Isoform Shows Reduced Phosphorylation In Vivo

Although there are clear differences in AMPKα localization dependent on the carboxy-terminal putative NES, we wondered what downstream consequences might be elicited. For example, LKB1, an upstream activator of AMPKα, requires cytoplasmic localization for activation (Baas et al., 2003; Boudeau et al., 2003a). To determine whether or not the differentially localized AMPKα, with or without the putative NES, might also affect the phosphorylation of the invariant Thr172 (Thr184 in Drosophila) that is required for AMPK activity (Lizcano et al., 2004), we measured the phosphorylation levels of Thr184 in transgenic Drosophila animals expressing either wild-type or truncated AMPKαΔC by Western blot. Quantification of phospho-AMPKα (pAMPKα) in either total lysates (Figure 7A) or immunoprecipitated AMPKα, normalized to total AMPKα levels (Figure 7B), indicates that only ∼20% of the truncated nuclear-enriched protein is phosphorylated relative to wild-type full-length protein.

Figure 7.

Phosphorylation of the activation loop threonine (T184) AMPKα is reduced in a nuclear enriched form in Drosophila in vivo and increased in the cytoplasmic form in human cells in vitro. (A) Western blot of total lysates from transgenic Drosophila flies expressing Gal4 alone, mCherry-tagged full-length AMPKα, or mCherry-tagged truncated AMPKα (AMPKαΔC) probed for phospho-AMPKα, total AMPKα, and Lamin C (loading control). (B) Western blot of proteins immunoprecipitated with anti-AMPKα antibody from fly lysates from the above fly lines, probed for phospho- and total AMPKα. Both AMPKα protein constructs are overexpressed using the Gal4-UAS system, driven by Ubiquitin-Gal4. (C) Heat-shock stress (■) on live larvae induces increased activation loop threonine phosphorylation (pAMPKα) of wild-type (mCherry-AMPKα) and endogenous (W1118) AMPKα but not AMPKα missing the NES (AMPKαΔC). Standardized to Lamin C as a loading control. (D) Cytoplasmic AMPKα isoforms, wild-type (WT), and WT substituted with the snurportin (SNUPN) NES, demonstrate increased activation loop threonine phosphorylation compared with the nuclear (L,L>A,A) isoform. Standardized to tubulin as a loading control.

We wondered whether the physiological stress of heat shock that causes AMPKα translocation into the nucleus (Figure 6) would have any consequences for AMPK function based on the well-known requirement that a conserved threonine in the AMPKα activation loop must be phosphorylated for AMPK activity (Lizcano et al., 2004). Indeed, although both endogenous untagged and wild-type mCherry-tagged AMPKα displayed dramatic increases in phospho-AMPKα upon heat shock, the version missing the NES showed no change in phospho-AMPKα (Figure 7C). Importantly, decreased phosphorylation of predominantly nuclear localized AMPKα appears to be highly conserved as cytoplasmic localization of AMPKα isoforms in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells show increased phospho-AMPKα compared with the nuclear-enriched AMPKα isoform (Figure 7D). The importance of phospho-AMPKα regulation as an indicator of AMPK activity is demonstrated by the tight regulation between introduced transgenic/exogenous phospho-AMPKα and resulting in decreased endogenous phospho-AMPKα levels (Supplementary Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

For enzymes in particular, subcellular protein localization plays a key role in the proper functioning of cells by enabling interaction with required substrates and preventing unwanted side reactions. Regulation of subcellular localization, studied for numerous nucleocytoplasmic-shuttling, signal-transducing proteins (Xu and Massague, 2004), adds an additional layer of complexity, enabling changes in access to substrates as well as upstream activators and inhibitors depending on the needs of the cell.

As an example, the upstream AMPK activator LKB1, under different stimuli, can localize to either the nucleus or cytoplasm, greatly affecting its own activity. Some LKB1 mutations that cause human Peutz-Jeghers syndrome constitutively sequester LKB1 to the nucleus and despite being outside the kinase domain, are phenotypically indistinguishable from mutations that abolish enzymatic activity (Nezu et al., 1999; Boudeau et al., 2003b; Xie et al., 2009). Although the mechanism of LKB1 localization is complex, it involves other proteins, including the STRADs (STE-related adapter) that form a complex with LKB1, promoting nuclear export and inhibiting nuclear import (Boudeau et al., 2003a; Dorfman and Macara, 2008). Although LKB1 is an upstream activator of AMPKα (Lizcano et al., 2004) and both proteins are kinases, LKB1 can function without other subunits bound, whereas AMPK is generally thought of as an obligate trimer (Hardie, 2007).

Previous studies have elucidated both nuclear and cytoplasmic targets of AMPK. In the cytoplasm, AMPK most notably phosphorylates and inhibits ACC, a rate-limiting enzyme required for fatty acid synthesis (Carling et al., 1989). Conversely, there are several known nuclear targets of AMPK (Leff, 2003; Bronner et al., 2004; Jager et al., 2007; Narkar et al., 2008), including PGC1α and PPARα/γ/δ, which regulate transcription in the nucleus. Furthermore, AMPK accumulation in or dispersion from the nucleus can be regulated by exercise, cellular stress, and circadian rhythms. In one study, exercise increased induced nuclear translocation of AMPKα2 in skeletal muscle (McGee et al., 2003), where AMPK is known to activate PGC1α and subsequent gene transcription (Jager et al., 2007). Another more recent study has demonstrated that AMPKα1 in the nucleus fluctuates in a circadian manner, regulating the circadian clock by inducing degradation of cryptochrome 1 (Lamia et al., 2009). Clearly, mechanisms that regulate AMPK subcellular localization are widely utilized to modulate its access to downstream substrates.

The nuclear pore complex (NPC) plays a key role as a molecular sieve to help compartmentalize proteins between nucleus and cytoplasm. Indeed, many nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins contain signals to direct them in and/or out through the NPC (Yasuhara et al., 2009). An AMPK trimer would far exceed the generally accepted nuclear pore diffusional cutoff size of 40 kDa (Gorlich and Kutay, 1999) and would thus also need such NPC shuttling signals. Despite distinct AMPK targets in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, the mechanisms for regulating its localization remain unclear, particularly in organisms that have only single α/β/γ subunits (e.g., Drosophila), where localization models based on different genetically encoded isoforms are not applicable.

One previous model for nuclear AMPK localization proposes that AMPKα2, but not AMPKα1, contains an NLS in the kinase domain that becomes functional only upon addition of leptin (Suzuki et al., 2007). Because not all organisms encode leptin and we did not observe any localization differences for AMPKα2 when mutating key residues in the proposed leptin-stimulated NLS in transfected HEK293 cells (data not shown), regulation of AMPK localization is likely cell type-dependent. This can also be seen in the differential localization between AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 isoforms in insulinoma cells (Salt et al., 1998), in contrast to HEK cells, where α1 and α2 localize similarly (data not shown). These effects are also seen with the β subunit, because only AMPKβ1 enriches in the nucleus upon mutation of two phosphorylation sites in HEK cells (Warden et al., 2001), whereas AMPK complexes containing β2 preferentially localize in the nucleus in C2C12 cells under leptin treatment (Suzuki et al., 2007). Distinct SNF1 β subunits are also thought to promote differential subcellular localization in yeast (Vincent et al., 2001). Altogether, these results suggest that cells differentially regulate AMPK localization, and thus activity, through multiple pathways, depending on their unique metabolic requirements and hormonal responses.

The findings herein identify amino acids at the carboxy-terminus of AMPKα that modulate its nuclear export (Figures 1 and 3) that are nearly universal, with these sequences found across phyla (Figures 1 and 3), closely matching the consensus sequence for the leucine-rich CRM1-dependent NESs (la Cour et al., 2004). Further, we identify a stress treatment in vivo, heat shock, which causes nuclear translocation of AMPKα, which requires the NES for increased phopho-AMPKα under this stressor. Because phosphorylation of the activation loop is required for AMPK activity, this mechanism might be expected to be beneficial for surviving physiological stress.

As C-terminally truncated AMPKα localizes to the nucleus in vitro in HEK cells and in vivo in Drosophila under unstressed conditions, this suggests that AMPKα is basally imported to the nucleus and that regulation of AMPK localization in response to stress would predominantly be affected through modulation of the export pathway. Adding further complexity, localization of the AMPK complex and partitioning of specific subunits may also be both cell type– and context-dependent. For instance, in multicellular organisms certain tissues (e.g., fat) provide energy to other tissues/organs (e.g., muscle) at their own expense. In these cases, AMPK activation likely leads to different physiological outcomes between cell types, such as increased lipid mobilization in fat cells versus increased lipid uptake in muscle cells. In these situations, differential localization of AMPK in distinct cell types could be used to generate these different cellular responses.

A further avenue of inquiry in regulation of AMPK localization is in the possible effects of posttranslational modification of AMPK subunits on the accessibility of the carboxy-tail of AMPKα. As the AMPKα carboxy-tail folds into a pocket formed by the α and β subunits after a long flexible loop (Amodeo et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2007), altering the strength of these interactions could change its accessibility to CRM1, thus activating or inhibiting nuclear export. Although there are conserved residues that could be posttranslationally modified in the AMPKα carboxy-tail adjacent to the putative NES, we have so far been unable to identify residues flanking the NES that change the subcellular localization of AMPKα in vitro or are required for genetic rescue in vivo, as described earlier. One tantalizing possibility is that the potential phosphoserine mutations in β1 increase nuclear localization of AMPK by enhancing β interactions with the AMPKα tail, thus blocking nuclear export.

Whatever mechanisms determine AMPK localization, they must take into account two general observations: 1) AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 are largely genetically and functionally redundant in the mouse and 2) many organisms encode only a single isoform for individual AMPK subunits. In many mouse strains AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 are genetically redundant as single α1 knockouts or α2 knockouts are viable, yet double knockouts are lethal (B. Viollet, personal communication), suggesting that different AMPKα isoforms are functionally redundant for activities required for life in vivo. Therefore the elucidation of mechanisms that regulate AMPKα subcellular localization beyond isoform distinctions, such as the ones identified in this study, is vitally important to the understanding AMPK regulation in vivo.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Andrew Wilde for generously providing the RanQ69L plasmid. We thank Dr. Tom Maynard for providing the pmCherry plasmids and Dr. Reuben Shaw for AMPK β/γ plasmids. We thank Drs. Dave Roberts and Mark Peifer for providing the UAS-GFP::APC2 transgenic flies. N.K. thanks Dr. Jrgang Cheng for invaluable technical advice. The LC28.26 antibody developed by Paul A. Fisher, and the 9E 10 antibody developed by J. Michael Bishop, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health MH073155 to J.E.B.

Abbreviations used:

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- dAMPK

Drosophila AMPK

- LMB

leptomycin B

- NES

nuclear export sequence

- NLS

nuclear localization sequence

- NPC

nuclear pore complex

- PKIA

protein kinase A inhibitor

- Snf1

sucrose nonfermenting 1

- SNUPN

snurportin 1.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0347) on August 4, 2010.

REFERENCES

- Amodeo G. A., Rudolph M. J., Tong L. Crystal structure of the heterotrimer core of Saccharomyces cerevisiae AMPK homologue SNF1. Nature. 2007;449:492–495. doi: 10.1038/nature06127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas A. F., Boudeau J., Sapkota G. P., Smit L., Medema R., Morrice N. A., Alessi D. R., Clevers H. C. Activation of the tumour suppressor kinase LKB1 by the STE20-like pseudokinase STRAD. EMBO J. 2003;22:3062–3072. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff F. R., Klebe C., Kretschmer J., Wittinghofer A., Ponstingl H. RanGAP1 induces GTPase activity of nuclear Ras-related Ran. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2587–2591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudeau J., Baas A. F., Deak M., Morrice N. A., Kieloch A., Schutkowski M., Prescott A. R., Clevers H. C., Alessi D. R. MO25alpha/beta interact with STRADalpha/beta enhancing their ability to bind, activate and localize LKB1 in the cytoplasm. EMBO J. 2003a;22:5102–5114. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudeau J., Sapkota G., Alessi D. R. LKB1, a protein kinase regulating cell proliferation and polarity. FEBS Lett. 2003b;546:159–165. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00642-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenman J. E., Temple B. R. Opinion: alternative views of AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2007;47:321–331. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner M., Hertz R., Bar-Tana J. Kinase-independent transcriptional co-activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha by AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem. J. 2004;384:295–305. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carling D., Clarke P. R., Zammit V. A., Hardie D. G. Purification and characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase. Copurification of acetyl-CoA carboxylase kinase and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase kinase activities. Eur J. Biochem. 1989;186:129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carling D., Zammit V. A., Hardie D. G. A common bicyclic protein kinase cascade inactivates the regulatory enzymes of fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 1987;223:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuderland D., Konson A., Seger R. Identification and characterization of a general nuclear translocation signal in signaling proteins. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:850–861. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. P., Carling D., Hardie D. G. Tissue distribution of the AMP-activated protein kinase, and lack of activation by cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase, studied using a specific and sensitive peptide assay. Eur. J. Biochem. 1989;186:123–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. P., Hawley S. A., Woods A., Carling D., Haystead T. A., Hardie D. G. Purification of the AMP-activated protein kinase on ATP-gamma-sepharose and analysis of its subunit structure. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;223:351–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Biswas A., Suel K. E., Jackson L. K., Martinez R., Gu H., Chook Y. M. Structural basis for leucine-rich nuclear export signal recognition by CRM1. Nature. 2009;458:1136–1141. doi: 10.1038/nature07975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman J., Macara I. G. STRADα regulates LKB1 localization by blocking access to importin-α, and by association with Crm1 and exportin-7. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:1614–1626. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornerod M., Ohno M., Yoshida M., Mattaj I. W. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell. 1997;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick E. D., Ramos S. B., Blackshear P. J. A unique C-terminal repeat domain maintains the cytosolic localization of the placenta-specific tristetraprolin family member ZFP36L3. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:14792–14800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801234200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F. B., Brenman J. E., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. Genes regulating dendritic outgrowth, branching, and routing in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2549–2561. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G., Fernandez C. S., Stapleton D., Auster A. S., Widmer J., Dyck J. R., Kemp B. E., Witters L. A. Non-catalytic beta- and gamma-subunit isoforms of the 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:8675–8681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlich D., Kutay U. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1999;15:607–660. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie D. G. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:774–785. doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie D. G., Carling D., Carlson M. The AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinase subfamily: metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:821–855. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerklotz D., Doring P., Bonzelius F., Winkelhaus S., Nover L. The balance of nuclear import and export determines the intracellular distribution and function of tomato heat stress transcription factor HsfA2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:1759–1768. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1759-1768.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B. R. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of APC regulates beta-catenin subcellular localization and turnover. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:653–660. doi: 10.1038/35023605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. P., Carlson M. Regulation of snf1 protein kinase in response to environmental stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:16838–16845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseli T. J., Walter M., van Denderen B. J., Katsis F., Witters L. A., Kemp B. E., Michell B. J., Stapleton D. AMP-activated protein kinase beta subunit tethers alpha and gamma subunits via its C-terminal sequence (186–270) J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13395–13400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager S., Handschin C., St-Pierre J., Spiegelman B. M. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12017–12022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodiha M., Rassi J. G., Brown C. M., Stochaj U. Localization of AMP kinase is regulated by stress, cell density, and signaling through the MEK→ERK1/2 pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1427–C1436. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00176.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutay U., Guttinger S. Leucine-rich nuclear-export signals: born to be weak. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- la Cour T., Kiemer L., Molgaard A., Gupta R., Skriver K., Brunak S. Analysis and prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2004;17:527–536. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamia K. A., et al. AMPK regulates the circadian clock by cryptochrome phosphorylation and degradation. Science. 2009;326:437–440. doi: 10.1126/science.1172156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff T. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates gene expression by direct phosphorylation of nuclear proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:224–227. doi: 10.1042/bst0310224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung S. W., Harreman M. T., Hodel M. R., Hodel A. E., Corbett A. H. Dissection of the karyopherin alpha nuclear localization signal (NLS)-binding groove: functional requirements for NLS binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:41947–41953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizcano J. M., et al. LKB1 is a master kinase that activates 13 kinases of the AMPK subfamily, including MARK/PAR-1. EMBO J. 2004;23:833–843. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y., Fukuda M., Nishida E. Evidence for existence of a nuclear pore complex-mediated, cytosol-independent pathway of nuclear translocation of ERK MAP kinase in permeabilized cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:41755–41760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee S. L., Howlett K. F., Starkie R. L., Cameron-Smith D., Kemp B. E., Hargreaves M. Exercise increases nuclear AMPK alpha2 in human skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2003;52:926–928. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina P. M., Swick L. L., Andersen R., Blalock Z., Brenman J. E. A novel forward genetic screen for identifying mutations affecting larval neuronal dendrite development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2006;172:2325–2335. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.051276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirouse V., Swick L. L., Kazgan N., St Johnston D., Brenman J. E. LKB1 and AMPK maintain epithelial cell polarity under energetic stress. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:387–392. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Narkar V. A., et al. AMPK and PPARdelta agonists are exercise mimetics. Cell. 2008;134:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezu J., Oku A., Shimane M. Loss of cytoplasmic retention ability of mutant LKB1 found in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;261:750–755. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin-Arbesfeld R., Townsley F., Bienz M. The APC tumour suppressor has a nuclear export function. Nature. 2000;406:1009–1012. doi: 10.1038/35023016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt I., Celler J. W., Hawley S. A., Prescott A., Woods A., Carling D., Hardie D. G. AMP-activated protein kinase: greater AMP dependence, and preferential nuclear localization, of complexes containing the alpha2 isoform. Biochem. J. 1998;334(Pt 1):177–187. doi: 10.1042/bj3340177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton D., Gao G., Michell B. J., Widmer J., Mitchelhill K., Teh T., House C. M., Witters L. A., Kemp B. E. Mammalian 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase non-catalytic subunits are homologs of proteins that interact with yeast Snf1 protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:29343–29346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom A. C., Weis K. Importin-beta-like nuclear transport receptors. Genome Biol. 2001;2:REVIEWS3008. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-6-reviews3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A., Okamoto S., Lee S., Saito K., Shiuchi T., Minokoshi Y. Leptin stimulates fatty acid oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene expression in mouse C2C12 myoblasts by changing the subcellular localization of the alpha2 form of AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:4317–4327. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02222-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent O., Townley R., Kuchin S., Carlson M. Subcellular localization of the Snf1 kinase is regulated by specific beta subunits and a novel glucose signaling mechanism. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1104–1114. doi: 10.1101/gad.879301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden S. M., Richardson C., O'Donnell J., Jr, Stapleton D., Kemp B. E., Witters L. A. Post-translational modifications of the beta-1 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase affect enzyme activity and cellular localization. Biochem. J. 2001;354:275–283. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis K. Regulating access to the genome: nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell. 2003;112:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B., et al. Structural basis for AMP binding to mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2007;449:496–500. doi: 10.1038/nature06161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z., Dong Y., Zhang J., Scholz R., Neumann D., Zou M. H. Identification of the serine 307 of LKB1 as a novel phosphorylation site essential for its nucleocytoplasmic transport and endothelial cell angiogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:3582–3596. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01417-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Massague J. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of signal transducers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:209–219. doi: 10.1038/nrm1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara N., Oka M., Yoneda Y. The role of the nuclear transport system in cell differentiation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009;20:590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., White R. L., Neufeld K. L. Phosphorylation near nuclear localization signal regulates nuclear import of adenomatous polyposis coli protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:12577–12582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230435597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.