Tonicity responsive binding protein (TonEBP) is a transcription factor that plays a key role in osmoprotection. Here, we demonstrate enhanced activity of prosurvival NF-κB—at the onset of hypertonic challenge that depends on p38 kinase—and Akt-dependent formation of p65-TonEBP complexes that bind to elements of NF-κB-responsive genes.

Abstract

Tonicity-responsive binding-protein (TonEBP or NFAT5) is a widely expressed transcription factor whose activity is regulated by extracellular tonicity. TonEBP plays a key role in osmoprotection by binding to osmotic response element/TonE elements of genes that counteract the deleterious effects of cell shrinkage. Here, we show that in addition to this “classical” stimulation, TonEBP protects cells against hypertonicity by enhancing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity. We show that hypertonicity enhances NF-κB stimulation by lipopolysaccharide but not tumor necrosis factor-α, and we demonstrate overlapping protein kinase B (Akt)-dependent signal transduction pathways elicited by hypertonicity and transforming growth factor-α. Activation of p38 kinase by hypertonicity and downstream activation of Akt play key roles in TonEBP activity, IκBα degradation, and p65 nuclear translocation. TonEBP affects neither of these latter events and is itself insensitive to NF-κB signaling. Rather, we reveal a tonicity-dependent interaction between TonEBP and p65 and show that NF-κB activity is considerably enhanced after binding of NF-κB-TonEBP complexes to κB elements of NF-κB–responsive genes. We demonstrate the key roles of TonEBP and Akt in renal collecting duct epithelial cells and in macrophages. These findings reveal a novel role for TonEBP and Akt in NF-κB activation on the onset of hypertonic challenge.

INTRODUCTION

The nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) transcription factor system is a crucial regulator of numerous physiological processes that exerts its effects by binding to κB sequence elements present in hundreds of genes involved in inflammation, immunity, cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. It ensues that inappropriate activation of NF-κB has been linked to most inflammatory diseases (Mattson and Meffert, 2006; Razani et al., 2008; Simmonds and Foxwell, 2008; Granic et al., 2009; Rangan et al., 2009; Vallabhapurapu and Karin, 2009). The exact role it plays depends on cell type, the nature of acting stimuli, and integrative coordination between NF-κB signaling and other signaling pathways. Although most research has focused on the critical role of NF-κB in innate and adaptive immunity, it is now firmly established that NF-κB plays a pivotal role in the physiology of tissues outside of the immune system.

Both cell surface receptor-mediated and nonreceptor-mediated pathways activate NF-κB. Toll-like/interleukin (IL)-1 receptors (TLR/IL-1Rs), nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors, and retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors recognize microbial patterns and activate NF-κB. Members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (TNFR) family bind TNF, CD40 ligand, lymphotoxin-β1, and B cell-activating factor belonging to the TNF family, leading to NF-κB activation. In addition, activation of antigen T- and B-cell receptors and other receptors, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) stimulate the NF-κB signaling pathway (Biswas and Iglehart, 2006; Vallabhapurapu and Karin, 2009). NF-κB inducers that act independently of a cell surface receptor include genotoxic stimuli such as phorbol esters, UV light, ionizing radiation, and oxidative stress. Receptor- and nonreceptor-mediated pathways typically converge on central components made up of inhibitor of κB (IκB) proteins, IκB kinases (IKKs), and NF-κB complexes. The major activation pathway by which most stimuli stimulate NF-κB activity is the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway (Hayden and Ghosh, 2004; Vallabhapurapu and Karin, 2009). In this pathway, an active IKK complex, comprising the catalytic subunits IKKα and IKKβ and the regulatory subunit IKKγ (NEMO), phosphorylates IκBα on Ser32 and Ser36, leading to its proteasomal degradation. This exposes a nuclear localization signal present in p65 (RelA), inducing nuclear translocation of the prototypical NF-κB p65/p50 complex. A regulatory feedback loop involving the induction of IκBα synthesis helps terminate p65/p50 activation. p65 activity is further regulated by numerous molecules, such as the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (PKAc), p38 kinase, and Akt (PKB) that interact with the NF-κB signaling pathway at various stages.

Extracellular osmolality induces a panoply of cellular changes, affecting various processes such as transporter/channel activity, transcriptional/translational activity, and intracellular signaling. Hypertonicity-induced cell shrinkage exerts harmful effects on cell function that if unchecked lead to apoptotic cell death. To avoid this, cell volume is immediately restored via a regulatory volume increase (RVI) mechanism. An adaptation process is subsequently triggered during which intracellular ionic strength is reduced. This involves increased signaling of various osmoprotective responses in which both mitogen-activated protein, kinases and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) play key roles (Nahm et al., 2002; Sheikh-Hamad and Gustin, 2004). Tonicity-responsive enhancer binding-protein (TonEBP or NFAT5), which belongs to the Rel/NFAT family of transcription factors, plays a critical role in RVI by controlling the expression of osmoprotective genes including heat-shock protein 70 and genes that mediate the intracellular accumulation of small organic osmolytes that reduce intracellular ionic strength without affecting protein function, such as aldose reductase (AR), sodium-chloride-betaine cotransporter (BGT1), and sodium-myo-inositol cotransporter (SMIT) (Burg et al., 2007; Kwon et al., 2009).

Numerous cell types throughout the body are exposed to aniosmotic environments. Environmental osmolality is greatest in the kidney where levels as high as 1200 mOsmol/kg can be reached at the tip of the inner medulla in humans. Hypertonicity was shown to increase NF-κB activity in both renal medullary interstitial cells and collecting duct principal cells (Hao et al., 2000; Hasler et al., 2008). In the latter study, we showed that increased NF-κB activity by hypertonicity relies on IKKβ, IκBα, and p65 activity. In the present study, we aimed at identifying additional intracellular components mediating NF-κB activation by hypertonicity in collecting duct principal cells and macrophages. We show that increased NF-κB activity by hypertonicity relies on an Akt-mediated increase of IκBα degradation, increased p65 nuclear translocation, an interaction between p65 and TonEBP, and binding of p65-TonEBP complexes to κB elements of NF-κB–responsive genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Transfection

mCCDcl1 and HepG2 cells were cultured as described previously (Gaeggeler et al., 2005; Vinciguerra et al., 2009) and mpkCCDcl4 cells (passages 28–34) were seeded on permeable filters (Transwell; Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA) as described previously (Hasler et al., 2005). For nuclear extract preparations and immunoprecipitation and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays requiring large quantities of protein, cells were grown on T-75 flasks (Corning Life Sciences). Cells were grown to confluence and then in serum- and hormone-free medium for 24 h before performing experiments. H36.12j cells are mouse hybrid precursor macrophages (Canono and Campbell, 1992) that adhere poorly to plastic supports. Cells (5 × 105/well) were added to 12 well plates and grown in suspension in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium containing 580 mg/l glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin G sodium (10,000 U/ml), and streptomycin sulfate (10,000 mg/ml) (Invitrogen). Cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 2 d and then exposed overnight to serum- and hormone-free medium before performing experiments. For all cells, iso-osmotic medium (300 mOsmol/kg) was made hypertonic (350–600 mOsmol/kg) by replacing a fraction of the medium (apical and basal for mCCDcl1 and mpkCCDcl4 cells grown on filters) with NaCl-enriched (1100 mOsmol/kg) medium. Medium osmolality was checked using an osmometer. Contrary to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), TNF-α and transforming growth factor (TGF)-α only increased NF-κB activity when applied to the basal medium of cells grown on filters. For this reason, NF-κB stimulation was limited to LPS and hypertonicity for experiments performed on mpkCCDcl4 cells grown on T-75 flasks.

Transfection was performed as described previously (Mordasini et al., 2005) by electroporating cells in the presence of either 1.2 nmol of Stealth RNAi small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Invitrogen; Table 1), 8 pmol of plasmid containing either eGFP, human TonEBP (Maouyo et al., 2002), constitutively active IKKβ (Mercurio et al., 1997), or super-repressor IκBα (Oyama et al., 1998) mutants, or 8 pmol of plasmid containing luciferase constructs. We have estimated previously that 70% of mpkCCDcl4 cells are efficiently transfected by electroporation (Hasler et al., 2006a). Transfected cells were grown in culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum for 24 h (6 h for cells transfected with RNA interference [RNAi]) and then in serum- and hormone-free medium for 24 h before performing experiments.

Table 1.

RNAi target sequence

| Targeted gene | RNAi sense primer |

|---|---|

| c-Jun | GAGAGCGGUGCCUACGGCUACAGUA |

| p38 kinase α | CCGACGACCACGTTCAGTTTCTCAT |

| MyD88 | CCAUUGCCAGCGAGCUAAUUGAGAA |

| TNFR1 | CCCAAGGAAAGUAUGUCCAUUCUAA |

| TNFR2 | CCUGGCCAAUAUGUGAAACAUUUCU |

| TonEBP | CCUAGUUCUCAAGAUCAGCAAGUAA |

| Scrambled TonEBP | CCUCUUACUAGAACUACGGAAGUAA |

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Analysis

Total mRNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin RNA II kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Machery Nagel, Düren, Germany). Reverse transcription and real-time PCR analysis were performed as described previously (Hasler et al., 2005). Primer sequences used for real-time PCR analysis are shown in Table 2. Mouse acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein (P0) was used as an internal standard, and data were analyzed as described previously (Hasler et al., 2006b). None of the stimuli, pharmacological compounds, or RNAi was found to significantly alter P0 expression, as exemplified in Supplemental Figure S1. Quantitative PCR was performed in triplicate.

Table 2.

Real-time PCR primer sequences

| Targeted gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| P0 | AATCTCCAGAGGCACCATTG | GTTCAGCATGTTCAGCAGTG |

| TNFα | GACCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCT | CCACTTGGTGGTTTGCTACGA |

| MCP-1 | GGCTCAGCCAGATGCAGTTAA | CCTACTCATTGGGATCATCTTGCT |

| IκBα | CGGAGGACGGAGACTCGTT | TTCACCTGACCAATGACTTCCA |

| p38 kinase α | CCTTGCCACTTTGGCTTCTC | AGCAGCCTCTCTCTGTCACTGA |

| c-Jun | GCAGAGAGGAAGCGCATGA | CCTTTTCCGGCACTTGGA |

| AR | AGTGCGCATTGCTGAGAACTT | GTAGCTGAGTAGAGTGGCCATGTC |

| BGT1 | CTGGGAGAGACGGGTTTTGGGTATTACATC | GGACCCCAGGTCGTGGAT |

| SMIT | CCGGGCGCTCTATGACCTGGG | CAAACAGAGAGGCACCAATCG |

| MyD88 | GCTCAACCCGTGTTCAATGA | GGTGGCTGGGAGGAAAGG |

| TNFR1 | TCCGCTTGCAAATGTCACA | GGCAACAGCACCGCAGTAC |

| TNFR2 | CTTGCGAAGCTGGCAGGTA | TGTCGACAGCTGCCAGAATG |

| ChIP | ||

| TNFα | CCCAACTCTCAAGCTGCTCT | CTTCTGAAAGCTGGGTGCAT |

| MCP-1 | ATCTGGAGCTCACATTCCA | TCCCTCTCACTTCACTCTGTCA |

| κBα | GCTTCTCAGTGGAGGACGAG | CTGGCTGAAACATGGCTGT |

| AR | CCAGTCGGTGCCCTCT | TTAGAGAAAAAGTACACCAGAATTTCC |

Western Blot Analysis

Preparation of cell lysates was performed as described previously (Hasler et al., 2005), and equal amounts of protein (10 μg) were separated by NuPage 4–12% BisTris gel (Invitrogen) electrophoresis. Bands were quantified using Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA). Experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results. Antibodies are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antibodies

| Host | Dilution | Manufacturer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary antibodies | |||

| p38 kinase | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA |

| Phospho-p38 kinase | Rabbit | 1:2500 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Phospho-ATF2 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Erk2 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA |

| Phospho-ERK1/2 | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Biotechnology |

| JNK1 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| JNK2 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Phospho-JNK1/2 | Mouse | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| c-Jun | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Phospho-c-jun | Mouse | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Akt | Rabbit | 1:2500 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Phospho-Akt (S473) | Rabbit | 1:2500 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| p50 | Mouse | 1:500 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| p65 | Mouse | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| IκBα | Rabbit | 1:2500 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| HDAC3 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Tubulinα | Mouse | 1:10000 | Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO |

| Na,K-ATPase α subunit | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Carranza et al. (1996) |

| PKAc | Rabbit | 1:2500 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| TonEBP | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Miyakawa et al. 1999 |

| Secondary antibodies | |||

| Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit | Goat | 1:20000 | BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA |

| HRP-conjugated anti-mouse | Goat | 1:20000 | BD Biosciences |

Luciferase Assay

Cells were transfected with either a TonE-driven luciferase plasmid p(kB)3 IFN-Luc containing three copies of TonE upstream of SV40 promoter and luciferase (Miyakawa et al., 1998) or a κB-driven luciferase plasmid containing three tandemly repeated κB motifs upstream of a minimal interferon (IFN)-β promoter (−55 to + 19) and luciferase (Fujita et al., 1993). Luciferase activity after 12 h of stimulation was measured using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The light produced was measured using a Lumat LB 9507 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany).

Immunoprecipitation

Cells grown on T-75 flasks were lysed in homogenizing buffer (HB: 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 40 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 30 mM NaF, 30 mM Na pyrophopshate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM AEBSF, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 0.5% saponin). Protein (500 μg–1 mg) was incubated overnight at 4°C with 10 μl of rabbit anti-TonEBP immunoglobulin (Ig)G, mouse anti-p65 IgG, or rabbit anti-Na,K-ATPase α subunit IgG. After 1 h of incubation with protein A-Sepharose beads, five washing steps were performed in HB. Precipitated proteins were separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and p65 or TonEBP was revealed by Western blotting.

Preparation of Nuclear and Cytosolic Extracts

Cells were scrapped off, spun at 1500 × g, and homogenized in lysis buffer A (10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM [4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonylfluoride], 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 4 μg/ml aprotinin) on ice for 10 min. The cell extract was then spun at 13,000 × g, and the supernatant, corresponding to cytosolic extract, was collected. The pellet was resuspended in the same lysis buffer and respun. The pellet was then resuspended in lysis buffer B (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 25% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 M EDTA, 1 mM [4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonylfluoride], 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 4 μg/ml aprotinin) on ice for 40 min and spun at 18,000 × g. The supernatant, corresponding to nuclear extract, was then collected. Cytosolic and nuclear extract (1 μg) was loaded on gels for Western blotting analysis.

ChIP

ChIP was performed as described previously (Hasler et al., 2008) by using antibodies against p65 and TonEBP (Table 3). Real-Time PCR of immunoprecipitated DNA fragments was performed as described above using primers shown in Table 2.

DNA Affinity Purification Analysis (DAPA)

Nuclear extracts obtained as described above were subjected to DAPA as described previously (Deng et al., 2003). DNA probes (15 nM) biotinylated on 5′ ends (Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland) and encoding κB sites of mouse TNF-α and MCP-1 promoters were mixed with 200 μg of nuclear extract, 50 μl of streptavidin-coated agarose beads, and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). The sequence of the primer against mouse TNF-α was 5′-AAGAACTCAAACAGGGGGCTTTCCCTCCTCAATATCAT and that against monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 was 5′-GGTCTGGGAACTTCCAATACTGCCTCAGAATGGGAATTTCCACGCTCT. The final volume was adjusted to 500 μl with nuclear lysis buffer B and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with end-over-end rotation. Beads were pelleted, washed four times with ice-cold phospate-buffered saline, and then resuspended in 50 μl of Laemmli sample buffer. Precipitated proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and identified by Western blot analysis using antibodies against TonEBP and p65 (Table 3).

Statistics

Results are given as the mean ± SE from n independent experiments. Each experiment was performed on cells from the same passage. All experiments were performed at least three times. Statistical differences were assessed using the student's t test (*p ≤ 0.05). No statistical differences between experimental points are depicted as NS.

RESULTS

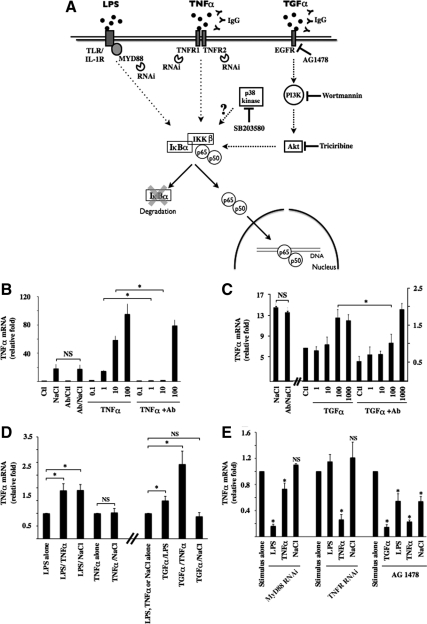

Hypertonicity Increases NF-κB Activity in a p38 Kinase-dependent Manner

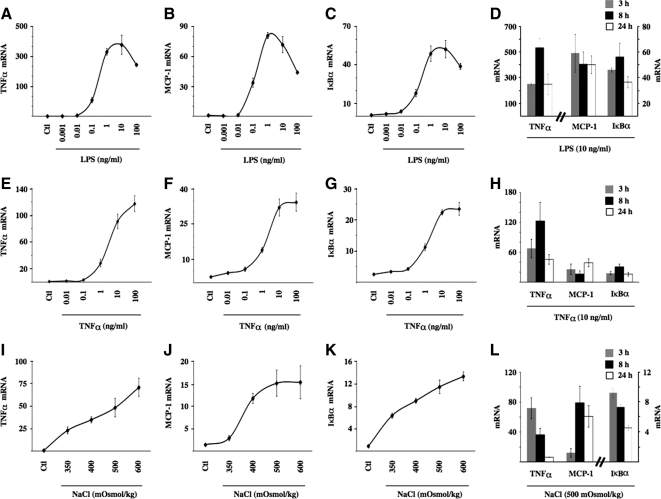

We demonstrated previously (Hasler et al., 2008) a transient increase of NF-κB activity occurring in mpkCCDcl4 cells exposed to NaCl- or sucrose-hypertonic medium but not urea-hyperosmotic medium (500 mOsmol/kg). In that study, NF-κB activity increased after 2 h of hypertonic challenge and returned toward baseline levels 24 h later. More recently, as revealed by increased levels of TNF-α mRNA expression, we reproduced the enhancer effect of hypertonicity in another cortical collecting duct cell line, mCCDcl1, and in nonrenal cell lines, such as hepatocytes and macrophages. In these cells, NF-κB activity increased 2- to 5-fold after 3 h of hypertonic challenge (500 mOsmol/kg). The most robust response, however, corresponding to a 40-fold increase of TNF-α mRNA expression, was achieved in mpkCCDcl4 cells. For this reason, we used this cell line to investigate intracellular events that mediate increased NF-κB activity on the onset of NaCl-hypertonic challenge. We sought to gain further insight on hypertonicity-inducible events affecting NF-κB signaling by comparing hypertonic effects with those elicited by TLR/IL-1R or TNFR activation. A comparison of mRNA expression levels between three NF-κB–dependent genes (TNF-α, MCP-1, and IκBα) revealed varying extents of NF-κB activation achieved by hypertonic, LPS, or TNF-α challenge (Figure 1). NF-κB activation was highest in cells challenged 3 h with 10 ng/ml LPS (Figure 1, A–C). These levels were at least twice as high as those achieved by 10 ng/ml TNF-α (Figure 1, E–G) and approximately 4 times as high as those induced by 500 mOsmol/kg hypertonic medium (Figure 1, I–K). Time-course experiments performed on all three NF-κB-dependent genes further revealed that the stimulatory effect of LPS and TNF-α was sustained for longer periods compared with that produced by hypertonicity (compare Figure 1, D and H, to L). In view of these results, unless explicitly stated, we used 10 ng/ml LPS, 10 ng/ml TNF-α, and 500 mOsmol/kg NaCl-hypertonic medium for 3 h for all experiments in this study.

Figure 1.

Hypertonicity increases NF-κB activity in mpkCCDcl4 cells. Real-time PCR analysis of TNF-α (A, E, and I), MCP-1 (B, F, and J), and IκBα (C, G, and K) transcripts in mpkCCDcl4 cells after 3 h of LPS (1 pg/ml–100 ng/ml), TNF-α (1 pg/ml–100 ng/ml), or NaCl-hypertonic challenge (350–600 mOsmol/kg). Data are normalized to acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 and is represented as fold induction over nonstimulated (Ctl) cells. Also shown are time course expression analysis of each transcript by LPS (10 ng/ml; D), TNF-α (10 ng/ml; H), and NaCl hypertonic challenge (500 mOsmol/kg; L).

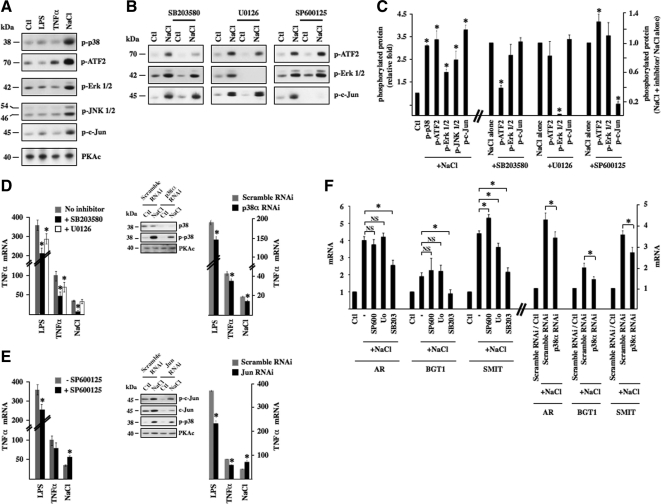

Activation of MAP kinase (MAPK) pathways is a hallmark of the hypertonic response. Phosphorylation of p38 kinase, p38 kinase substrate ATF2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), and JNK substrate c-Jun was especially high after 30 min of hypertonic but not LPS or TNF-α challenge (Figure 2, A and C), returning toward baseline levels after 3 h of challenge (data not shown). Total MAPK protein expression was not altered by any stimulus (data not shown). To investigate the influence of each of these MAPKs on hypertonicity-inducible NF-κB activation, we measured the effects of pharmacological inhibition of p38 kinase, ERK, and JNK. A comparison of ATF2 (used as an indicator for p38 kinase activity), ERK and c-Jun (used as an indicator for JNK activity) phosphorylation revealed that each inhibitor (10 μM SB203580 against p38 kinase, 10 μM U0126 against mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase [MEK], and 10 μM SP600125 against JNK) decreased its targeted protein activity but not the activities of the other two kinases, in response to 30 min of hypertonic challenge (Figure 2, B and C). Pharmacological inhibition of either p38 kinase, ERK, or JNK activity decreased NF-κB activity induced by 3 h of LPS or TNF-α challenge, as suggested by decreased TNF-α mRNA expression (Figure 2, D and E, left). Pharmacological inhibition of p38 kinase, but not ERK, activity, greatly reduced TNF-α transcript accumulation after 3 h of hypertonic challenge. RNAi against p38α kinase mimicked the attenuating effect of SB203580 on increased TNF-α mRNA expression by either LPS, TNF-α, or hypertonic challenge, although the inhibitory effect was smaller (Figure 2D, right). Altered MCP-1 and IκBα mRNA expression in response to pharmacological MAP kinase inhibition is shown in Supplemental Figure S3. Notably, although SB203580 blunted the hypertonicity-induced increase of MCP-1 mRNA expression, IκBα mRNA expression was unchanged. Unexpectedly, the stimulatory effect of hypertonicity was enhanced by JNK inhibition (Figure 2C). We further investigated this effect by RNAi knockdown against c-Jun. c-Jun protein expression increased in response to 3 h of hypertonic challenge, whereas RNAi efficiently decreased expression of both total and phosphorylated pools of c-Jun (Figure 2C). The effects of RNAi c-Jun knockdown on inducible TNF-α mRNA expression echoed those obtained by pharmacological JNK inhibition, i.e., a decrease of LPS and TNF-α inducibility and enhanced inducibility by hypertonicity. Increased TNF-α expression in response to c-Jun knockdown was moreover found to occur despite decreased p38 kinase phosphorylation (Figure 2C). These results suggest that NF-κB activation by hypertonicity is repressed by JNK but partly depends on p38 kinase activity. We focused our investigations on this latter dependence.

Figure 2.

NF-κB activation by hypertonicity in part depends on p38 kinase activity. (A) Protein lysates from cells challenged or not (Ctl) with either LPS, TNF-α, or hypertonic medium (NaCl) were analyzed by immunoblot for phosphorylated forms of p38 kinase, p38 substrate ATF2, ERK, JNK, and JNK substrate c-Jun. PKAc was used as a loading control. (B) Protein lysates from cells pretreated or not for 30 min with 10 μM SB203580 (a p38 kinase inhibitor), 10 μM U0126 (a MEK inhibitor), or 10 μM SP600125 (a JNK inhibitor) and then challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium were analyzed by immunoblot for phosphorylated forms of ATF2, ERK, and c-Jun. (C) Fold protein phosphorylation following hypertonic challenge over baseline levels (Ctl) is shown at left. Fold decrease of protein phosphorylation by pharmacological inhibitors in hypertonicity-challenged cells is shown at right. (D and E) Real-time PCR analysis of TNF-α transcript after LPS, TNF-α, or hypertonic challenge in the presence or absence of either SB203580 or U0126 (D, left) or SP600125 (E; left). (D and E) Right, effects of SB203580 and SP600125 on TNF-α transcript expression were echoed by RNAi against p38α (D) or c-Jun (E), respectively. Immunoblots depicting decreased expression levels of target protein by RNAi are also shown. PKAc was used as a loading control. (F) Left, real-time PCR analysis of AR, BGT1, and SMIT transcripts in cells treated or not with a pharmacological inhibitor and challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium. Data are represented as fold induction over nonstimulated cells in the absence of an inhibitor. Similar to SB203580, RNAi against p38α reduced the enhancer effect of hypertonicity on AR, BGT1, and SMIT transcript expression (right). The effects of pharmacological compounds and RNAi on basal mRNA expression levels for this and all other figures are shown in Supplemental Figure S2.

TonEBP Mediates Increased NF-κB Activity by Hypertonicity

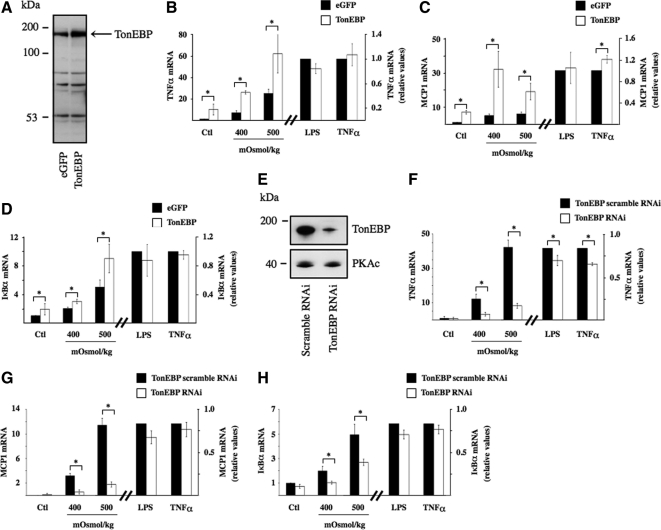

TonEBP is a major transcription factor whose activity is regulated by extracellular tonicity. Results of previous studies provide evidence that p38 kinase signaling contributes to TonEBP activity (Nadkarni et al., 1999; Ko et al., 2002; Irarrazabal et al., 2008; Kuper et al., 2009). In this study, with the exception of a small but significant decrease of SMIT mRNA expression by U0126, we found that inhibition of p38 kinase activity by SB203580, but not ERK or JNK activity by their respective pharmacological inhibitors, decreased TonEBP activity under hypertonic conditions, as revealed by reduced levels of AR, BGT1, and SMIT mRNA expression (Figure 2F, left). It should be noted that TonEBP activity was previously found to be enhanced by p38α but inhibited by p38δ (Zhou et al., 2008). Because the activities of both p38 isoforms are increased by hypertonicity (Zhou et al., 2008), it is possible that their opposing effects may negate any effect on TonEBP activity. SB203580 inhibits p38α but not p38δ activity (Gum et al., 1998). Regardless of whether decreased TonEBP activity shown in Figure 2D arises from decreased p38α activity or unmasked p38δ activity, these data suggest that p38 kinase helps modulate TonEBP activity. This is supported by the observation that increased AR, BGT1, and SMIT mRNA expression by hypertonicity was slightly but significantly reduced in cells transfected with RNAi against p38α kinase (Figure 2F, right). These observations led us to investigate a possible role for TonEBP in hypertonicity-induced NF-κB activation. We proceeded by comparing the effects of 3 h hypertonic challenge (400 and 500 mOsmol/kg) in cells transfected with cDNA encoding TonEBP that express high levels of TonEBP protein (Figure 3A) and cells transfected with RNAi against TonEBP that express low levels of TonEBP protein (Figure 3E). TonEBP activity in response to hypertonicity was enhanced in cells expressing high levels of TonEBP protein, as demonstrated by a 50% increase of TonEBP-dependent luciferase activity and a 50% and sevenfold increase of AR and BGT1 mRNA expression, respectively, compared with cells transfected with cDNA encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP; data not shown). We demonstrated previously strong down-regulation of TonEBP activity by TonEBP RNAi (Hasler et al., 2006a).

Figure 3.

TonEBP mediates NF-κB activation by hypertonicity. (A and E) Immunoblot of protein lysates from cells transfected with cDNA encoding eGFP or TonEBP (A) or transfected with scrambled RNAi or RNAi against TonEBP (E). The arrow in A depicts the band corresponding to TonEBP. In E, PKAc was used as a loading control. (B–D and F–H) real-time PCR analysis of TNF-α, MCP-1, and IκBα transcripts in cells transfected with cDNA encoding eGFP or TonEBP (B–D) or transfected with scrambled RNAi or RNAi against TonEBP (F–H) and challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium (400 or 500 mOsmol/kg), LPS, or TNF-α. Data are represented as fold induction over nonstimulated cells transfected with eGFP or scrambled RNAi.

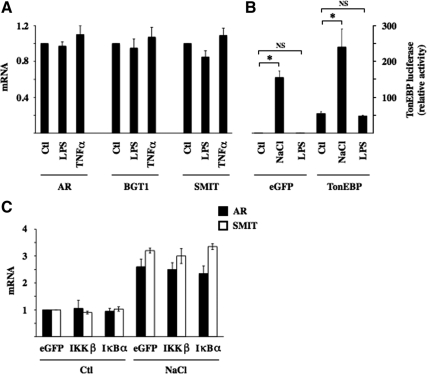

High levels of TonEBP expression enhanced NF-κB activation by hypertonicity, as demonstrated by increased TNF-α, MCP-1, and IκBα mRNA expression (Figure 3, B–D). Inversely, low levels of TonEBP expression reduced NF-κB activation by hypertonicity, as shown by decreased TNF-α, MCP-1, and IκBα mRNA expression (Figure 3, F–H). These results show that the stimulatory effect of hypertonicity on NF-κB activity depends at least in part on TonEBP activity. Conversely, NF-κB activation by LPS or TNF-α was only marginally affected by changes in TonEBP expression (Figure 3), indicating that the influence of TonEBP on NF-κB activity is predominately governed by increased TonEBP activity by hypertonic challenge. We next investigated whether “classical” NF-κB stimuli affect TonEBP activity. Neither LPS nor TNF-α affected TonEBP-dependent gene transcription (Figure 4A). LPS had no effect on TonEBP-induced luciferase activity, even in cells overexpressing TonEBP (Figure 4B). We demonstrated previously the enhancing and repressive effects of constitutively active IKKβ and super repressor IκBα mutants on NF-κB activity in transfected mpkCCDcl4 cells (Vinciguerra et al., 2005; Leroy et al., 2007; Hasler et al., 2008). We show here that TonEBP-dependent gene transcription is not affected by either mutant under either isotonic or hypertonic conditions (Figure 4C), providing additional evidence that TonEBP is not sensitive to stimuli that increase canonical NF-κB signaling. Together, these results show that TonEBP activity is not influenced by canonical NF-κB signaling and that although it plays a key role in mediating NF-κB activation by hypertonicity, its role in mediating LPS or TNF-α signaling is less obvious.

Figure 4.

IKKβ and IκBα do not influence TonEBP activity. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of AR, BGT1, and SMIT transcripts in cells challenged with LPS or TNF-α. Data are represented as fold expression over nonstimulated (Ctl) cells. (B) TonEBP-driven luciferase activity in response to hypertonic (NaCl) or LPS challenge. Cells were transfected with p(kB)3 IFN-Luc plasmid and cotransfected with cDNA encoding either eGFP or TonEBP. Data shown is represented as fold induction over nonstimulated cells transfected with cDNA encoding eGFP. (C) Real-time PCR analysis of AR and SMIT transcripts in cells transfected with cDNA encoding eGFP or constitutively active IKKβ or IκBα and challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium. Data shown is represented as fold induction over nonstimulated cells transfected with cDNA encoding eGFP.

Increased NF-κB Activity by Hypertonicity Relies on Akt Kinase Signaling

TonEBP has been shown previously to bind to a TonE element present in the TNF-α promoter (Lopez-Rodriguez et al., 2001; Esensten et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2008; Hao et al., 2009) and such elements might be present in the promoters of other NF-κB–sensitive genes, including MCP-1 and IκBα as well. However, we demonstrated previously that super repressor IκBα mutant and RNAi against p65 significantly reduce NF-κB activation by hypertonicity (Hasler et al., 2008). TonEBP activity is not affected by canonical NF-κB signaling (Figure 4), strongly suggesting that controlled gene transcription by TonEBP is mediated both by its interaction with TonE elements of NF-κB–sensitive genes, if present, and additionally by its interaction with elements of the NF-κB pathway. Our next aim was to identify hypertonicity-inducible elements that participate in IKKβ activation. We proceeded by comparing the effects of hypertonicity to those induced by LPS and TNF-α. A summary of the tools used for this study is shown in Figure 5A. Data suggesting that hypertonicity stimulates EGFR (Rosette and Karin, 1996) and that active EGFR stimulates both NF-κB (Sun and Carpenter, 1998; Sethi et al., 2007) and TonEBP (Kuper et al., 2009) led us to additionally compare the effects of hypertonicity to those induced by active EGFR. Numerous molecules bind to EGFR eliciting its activation. In particular, TGF-α was proposed to contribute to TonEBP activation by hypertonicity (Kuper et al., 2009). For this reason, we used TGF-α as an EGFR agonist. Using an antibody neutralization approach, we first show that NF-κB activation by hypertonicity does not arise from autocrine secretion of either TNF-α or TGF-α (Figure 5, B and C). Indeed, although antibodies against either TNF-α or TGF-α effectively quenched ligand ability to induce NF-κB activity in a dose-dependent manner, they did not affect NF-κB activation by hypertonicity. Of course, we cannot rule out the possibility that secretion of other molecules may initiate hypertonic signaling. We next investigated whether NF-κB activation by LPS, TNF-α, or TGF-α is affected by hypertonicity. Although TNF-α mRNA expression by LPS was enhanced by either TNF-α or hypertonic challenge, that elicited by TNF-α (100 ng/ml) was not affected by hypertonicity (Figure 5D). In addition, although TGF-α increased the effects of both TNF-α and LPS, it did not affect the hypertonic response (Figure 5D). Supplemental Figure S4A shows that changes in TNF-α mRNA expression were echoed by changes in MCP-1 and IκBα mRNA expression. We examined the effects of down-regulated TLR/IL-1R, TNFR, and EGFR activity on NF-κB activation by hypertonicity by using RNAi against MyD88, RNAi against TNFR1 and TNFR2, and the EGFR antagonist AG1478 (10 μM), respectively (Figure 5E). RNAi against MyD88 effectively reduced target mRNA expression (by 86 ± 1%) and reduced LPS-induced NF-κB activity to a much greater extent than that induced by TNF-α. RNAi against TNFR reduced target mRNA expression (by 90 ± 1 and 46 ± 4% for TNFR1 and TNFR2, respectively) and reduced TNF-α but not LPS signaling. Importantly, as indicated by changes in TNF-α mRNA expression, and also by similar changes in MCP-1 and IκBα mRNA expression (Supplemental Figure S4B), NF-κB activation by hypertonicity was not affected by down-regulated signaling of either TLR/IL-1R or TNFR. Decreased EGFR signaling by AG1478, in contrast, reduced not only the effects of TGF-α but also those elicited by LPS, TNF-α, and hypertonicity. Supplemental Figure S4 shows that although changes in MCP-1 mRNA expression echoed those observed for TNF-α mRNA, IκBα mRNA expression was insensitive to both TFGα stimulation and AG1478. Together, these results are indicative of common intracellular elements between hypertonicity and TGF-α and TNF-α, but not LPS, signaling pathways.

Figure 5.

NF-κB signaling by hypertonicity overlaps that elicited by TNF-α and TGF-α. (A) Schematic illustration of NF-κB activation by LPS, TNF-α, and TGF-α. Binding of each ligand to partner receptors initiates distinct transduction cascades that all ultimately lead to IKKβ activation. Under basal states, IκBα interacts with p65, retaining it in the cytoplasm. Once activated, IKKβ typically phosphorylates IκBα, leading to its degradation. This allows nuclear translocation of liberated p65-containing complexes, typically p65-p50 dimers. Tools used in this study to investigate the putative roles of target molecules in hypertonic NF-κB inducibility are shown. Also shown is p38 kinase whose role in NF-κB activation by hypertonicity was investigated. (B and C) Real-time PCR analysis of TNF-α transcript in cells challenged with hypertonic medium (NaCl, 500 mOsmol/kg), TNF-α (0.1–100 ng/ml), or TGF-α (1–1000 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of IgG against TNF-α (B) or TGF-α (C). Data are represented as fold induction over nonstimulated (Ctl) cells. (D) Real-time PCR analysis of TNF-α transcript in cells challenged with LPS, TNF-α, TGF-α (100 ng/ml), or hypertonic medium alone or simultaneously challenged with two stimuli. Data are represented as fold expression over cells challenged with LPS, TNF-α, or hypertonicity alone. (E) Real-time PCR analysis of TNF-α transcript in cells transfected with scrambled RNAi, RNAi against MyD88, or RNAi against TNFR1 and TNFR2 or cells treated with 10 μM of the EGFR antagonist AG1478. Cells were challenged with LPS, TNF-α, TGF-α, or hypertonic medium. Data are represented as fold expression over cells challenged with either stimulus alone.

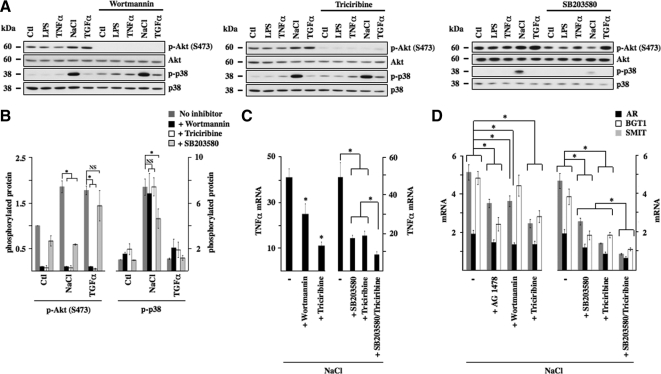

Akt is a major target of EGFR (Citri and Yarden, 2006). We examined a putative role for Akt in hypertonicity-induced NF-κB signaling by measuring the effects of pharmacological inhibition of PI3-kinase and its downstream target Akt (Figure 6). Increased Akt phosphorylation after 30 min of TGF-α or hypertonic stimulation, but not LPS or TNF-α stimulation, was efficiently reduced by 30-min preincubation in the presence of either wortmannin (100 nM), a PI3-kinase inhibitor, or triciribine (30 μM), an inhibitor of Akt (Figure 6, A and B). Interestingly, decreased Akt phosphorylation by either pharmacological agent did not influence p38 kinase phosphorylation by hypertonicity, whereas SB203580 abolished Akt phosphorylation by hypertonicity but not by TGF-α (Figure 6, A and B). Similar results were obtained using another p38 kinase inhibitor (SB202190; data not shown). These results indicate that p38 kinase at least partly mediates increased Akt kinase activity by hypertonicity. TGF-α challenge alone, which does not induce p38 kinase phosphorylation, failed to elicit TonEBP-dependent gene transcription (data not shown). Alternatively, despite normal levels of p38 kinase phosphorylation, AG1478, wortmannin, and triciribine all reduced TonEBP-dependent gene transcription in response to hypertonicity and TonEBP activity was most efficiently reduced by simultaneous inhibition of p38 kinase and Akt activity (Figure 6D). These results indicate that increased TonEBP activity by hypertonicity is mediated by both p38 kinase and Akt. Reflecting reduced TonEBP activity, inhibition of PI3-kinase and Akt activity reduced TNF-α mRNA expression by hypertonicity as well, with maximal reduction after simultaneous inhibition of both p38 kinase and Akt activity (Figure 6C). Supplemental Figure S5 shows that although changes in MCP-1 mRNA expression echoed those of TNF-α mRNA, neither wortmannin nor triciribine decreased hypertonicity-induced IκBα mRNA expression. Together, these results demonstrate that activation of TonEBP and NF-κB by hypertonicity depends on increased activity of both p38 kinase and Akt.

Figure 6.

p38 kinase and Akt mediate NF-κB activation by hypertonicity. (A) Immunoblot of protein lysates against Akt phosphorylated at Ser473, nonphosphorylated Akt, and phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated p38 kinase. Cells were treated or not with 100 nM wortmannin (a PI3-kinase antagonist), 30 μM triciribine (an Akt antagonist), or 10 μM SB203580 (a p38 kinase antagonist) and challenged or not (Ctl) with LPS, TNF-α, TGF-α, or hypertonic medium (NaCl). (B) Fold expression of phosphorylated Akt and phosphorylated p38 kinase by either hypertonicity or TGF-α in the presence or absence of a pharmacological inhibitor over that of nonstimulated (Ctl) cells. (C and D) Real-time PCR analysis of TNF-α transcript (C) or AR, BGT1 and SMIT transcripts (D) in cells challenged with hypertonic medium in the presence or absence of wortmannin, triciribine (C) or wortmannin, triciribine or AG1478 (10 μM) (D). The effects of SB203580 and triciribine, applied alone or together, on hypertonic stimulation of TNF-α expression and TonEBP activity is shown at right of each figure. Data are represented as fold decrease of hypertonicity-induced mRNA expression by pharmacological inhibitors.

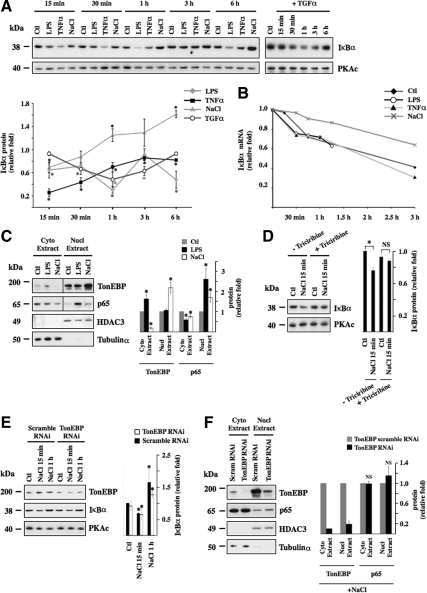

Hypertonicity Induces Akt-dependent, but TonEBP-independent, IκBα Degradation and p65 Nuclear Translocation and Induces Interactivity between p65 and TonEBP

Super-repressor IκBα effectively blunts increased NF-κB activity by hypertonicity (Hasler et al., 2008). This incited us to compare IκBα degradation by hypertonicity to that induced by LPS, TNF-α, or TGF-α (Figure 7A). Although all four stimuli elicited IκBα degradation, each stimulus produced a different time-dependent degradation signature. LPS-induced IκBα degradation greatly varied over time, whereas that induced by TGF-α gradually increased to reach maximal levels after 1 h of stimulation after which IκBα expression increased. TNF-α and hypertonicity produced similar degradation patterns, although IκBα degradation in response to TNF-α was greater than that after hypertonic challenge. Interestingly, hypertonicity was the only stimulus observed to increase IκBα expression, an event that was already induced after 1 h of stimulation. IκBα degradation at the onset of hypertonic challenge is most likely supplanted by the combined effects of novel IκBα protein synthesis and the stabilizing effect of hypertonicity, but not LPS or TNF-α, on IκBα mRNA (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Hypertonicity induces IκBα degradation and p65 nuclear translocation independently of TonEBP. (A) Immunoblot of protein lysates against IκBα or PKAc (used as a loading control) in cells challenged or not (Ctl) with LPS, TNF-α, hypertonic medium (NaCl), or TGF-α for various times. Time-dependent IκBα degradation by each stimulus is represented as fold IκBα expression in stimulated cells at each time point over nonstimulated cells. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of IκBα transcript in cells pretreated 15 min with actinomycin D (10 μM) and then challenged or not (Ctl) with LPS, TNF-α, or hypertonic medium for various times. Data are represented as fold IκBα transcript expression in stimulated cells over that of nonstimulated cells before addition of actinomycin D. (C) Immunoblot of cytoplasmic and nuclear protein lysates against TonEBP, p65, histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3, (used as a loading control for nuclear extracts), and Tubulinα (used as a loading control for cytosolic extracts) in cells challenged or not (Ctl) with LPS or hypertonic medium for 30 min. Fold TonEBP and p65 expression in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts over that of nonstimulated cells (Ctl) is shown at right. (D and E) Immunoblot of protein lysates against IκBα, PKAc (used as a loading control) (D) and TonEBP (E) in cells pretreated or not with Akt antagonist triciribine and then challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium for 15 min (D) or in cells transfected with scrambled RNAi or TonEBP RNAi and then challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium for 15 min or 1 h (E). IκBα protein expression is represented as fold expression over control cells. (F) Immunoblot of cytoplasmic and nuclear protein lysates against TonEBP, p65, HDAC3, and Tubulinα in cells transfected with scrambled RNAi or TonEBP RNAi and challenged with hypertonic medium for 30 min. Fold TonEBP and p65 expression in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts over that of cells transfected with TonEBP scrambled RNAi is shown at right.

In addition to inducing IκBα degradation, hypertonic challenge instigated redistribution of p65 from a cytoplasmic pool to a nuclear pool (Figure 7C). This contrasts with previous observations by immunofluorescence microscopy that found no effect of hypertonicity on p65 subcellular localization (Lopez-Rodriguez et al., 2001). Our immunofluorescence microscopy analysis of mpkCCDcl4 cells revealed that although LPS increased p65 nuclear translocation, the effect produced by hypertonicity was less obvious (data not shown). In view of these results, we believe that Western blotting of cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extracts is more appropriate in detecting small changes of p65 distribution between nuclear and cytosolic compartments. As expected from previous observations (Figure 4), hypertonicity increased TonEBP nuclear localization, whereas LPS had no effect. We investigated a putative role of TonEBP in the hypertonicity-induced increase of IκBα degradation/p65 nuclear import. Although pharmacological inhibition of Akt blunted IκBα degradation by hypertonicity (Figure 7D), RNAi against TonEBP did not affect the alterations of IκBα expression that follow hypertonic challenge (Figure 7E). Similarly, reduced TonEBP expression had no effect on p65 nuclear translocation after 30 min of hypertonic challenge (Figure 7F). Together, these data indicate that TonEBP does not influence either IκBα degradation or nuclear translocation of p65-containing NF-κB complexes on the onset of hypertonic challenge.

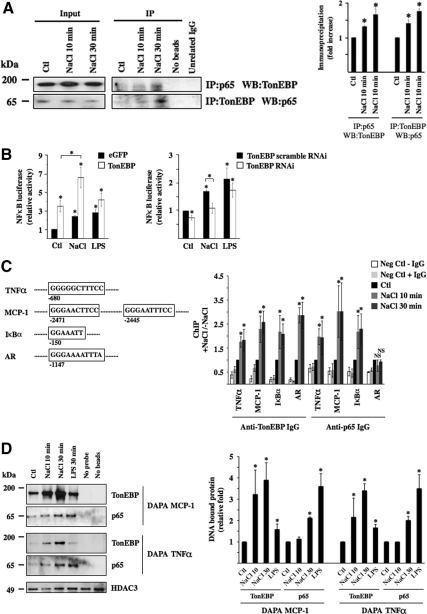

We next investigated whether TonEBP associates with p65. Antibodies against p65 and TonEBP were found to coimmunoprecipitate TonEBP and p65, respectively, under hypertonic conditions (Figure 8A). Although visible under isotonic conditions, the intensity of immunoprecipitated bands increased along with the duration of hypertonic challenge (10 vs. 30 min of challenge). Luciferase activity, driven by a promoter containing κB but not TonE motifs (Fujita et al., 1993) was increased after 12 h of either LPS or hypertonic challenge (Figure 8B). Importantly, TonEBP overexpression enhanced, and RNAi against TonEBP reduced, luciferase activity by hypertonicity to greater extents than that achieved by LPS. This indicates that increased NF-κB activity by hypertonicity is not only dependent on binding of TonEBP to TonE elements in target genes, if present, but also on an interaction between TonEBP and p65 protein, as shown in Figure 8A. ChIP and DAPA experiments show that such an interaction occurs at κB elements within minutes of stimulation (Figure 8, C and D). Indeed, ChIP experiments revealed that antibodies against either p65 or TonEBP were able to immunoprecipitate DNA fragments containing κB elements located in TNF-α, MCP-1, or IκBα promoters. Immunoprecipitation of these fragments increased in response to hypertonicity. In contrast, only the anti-TonEBP antibody immunoprecipitated DNA fragments containing a TonE sequence located in the AR promoter, suggesting that p65 does not complex with TonEBP bound to TonE elements. For DAPA experiments, we used biotinylated double-stranded DNA fragments containing κB binding sites located in TNF-α or MCP-1 promoters as bait to pull down protein complexes bound to the DNA. Consistent with results obtained from ChIP experiments, hypertonicity increased the abundance of TonEBP bound to either DNA fragment. Although the highest signal corresponding to precipitated p65 was obtained from cells challenged 30 min with LPS, that corresponding to precipitated TonEBP was obtained from cells challenged 30 min with hypertonic medium (Figure 8C). Collectively, data (Figure 8) show that 1) TonEBP interacts with p65, 2) this interaction increases with environmental tonicity within minutes of stimulation, 3) the presence of TonE sites is not mandatory for this interaction, and 4) p65-TonEBP complexes bind κB but not TonE elements.

Figure 8.

TonEBP associates with p65 on the onset of hypertonic challenge. (A) Immunoblot against p65 and TonEBP immunoprecipitated by anti-TonEBP or anti-p65 IgG, respectively, or unrelated IgG (Na,K-ATPase α subunit) in cells challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium (NaCl) for 10 or 30 min. Also shown is the absence of bands from lysates precipitated in the absence of either agarose beads or IgG. Similar amounts of p65 and TonEBP between experimental conditions were loaded onto gels before immunoprecipitation (Input, corresponding to 5% of immunoprecipitated protein). Fold immunoprecipitated TonEBP and p65 over that of nonstimulated cells (Ctl) is shown at right. (B) NF-κB–driven luciferase activity in response to hypertonic (NaCl) or LPS challenge. Cells were transfected with a NF-κB-Luc plasmid described in Materials and Methods and cotransfected with cDNA encoding either eGFP or TonEBP (left) or with scrambled RNAi or RNAi against TonEBP (right). Data shown is represented as fold induction over nonstimulated cells transfected either with cDNA encoding eGFP or scrambled RNAi. (C) ChIP analysis. The localization of κB sites of mouse TNF-α, MCP-1, and IκBα promoters as well as the TonE site of mouse AR promoter chosen for analysis is shown. Localization is relative to the AUG start codon. Cells were challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium for 10 or 30 min before DNA fragmentation and immunoprecipitation using anti-TonEBP or p65 antibodies. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR using primers flanking κB sites of TNF-α, MCP-1, or IκBα promoters or the TonE site of the AR promoter. Data are represented as fold induction over nonstimulated cells. Negative controls consisted of DNA fragments precipitated in the absence of antibody or with anti- Na,K-ATPase α subunit IgG. (D) DAPA experiments were performed on nuclear extracts of cells challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium for 10 or 30 min or with LPS for 30 min. Precipitated protein by DAPA probes encompassing κB sites of MCP-1 or TNF-α promoters depicted in C was analyzed by immunoblot using anti-TonEBP or anti-p65 IgG. Equal loading was verified by immunoblot against histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3). Negative controls consisted of protein precipitated in the absence of either a DAPA probe or beads. Precipitated TonEBP and p65 protein was quantified and is graphically represented as fold expression over control cells.

It is worth pointing out at this point observations depicted in Figure 8 that may shed some light on the kinetics of p65-TonEBP interactivity by hypertonicity. Both immunoprecipitation experiments (Figure 8A) and DAPA experiments using anti-p65 IgG (Figure 8D) revealed that p65 and TonEBP interaction increased over time. Alternatively, no time-dependent differences were observed in DAPA experiments by using anti-TonEBP IgG, although a nonsignificant increase was observed (Figure 8D). Together, these results suggest that at early time points, the subpopulation of p65 interacting with TonEBP at κB elements, as opposed to the entire p65 pool, is too small to be readily observed by DAPA experiments by using anti-p65 IgG. In contrast, the TonEBP pool interacting with p65 at κB elements after short periods of challenge is large enough to produce a signal readily visible by DAPA using anti-TonEBP IgG. After longer periods of challenge, as p65-TonEBP interactivity increases, a sufficient pool of p65 interacts with TonEBP at κB elements, allowing visualization of p65-TonEBP complexes by DAPA using either anti-p65 or anti-TonEBP IgG. Such time-dependent variations were not observed in ChIP experiments (Figure 8C). However, these subtle differences may very well be masked by experimental variability.

Hypertonicity Induces TonEBP- and Akt-dependent NF-κB Activation in Macrophages

Cytokine production by macrophages constitutes a major part of the inflammatory response. Numerous studies have focused on determining the effects of hypertonicity on cytokine production and these led to seemingly contradictory results (Kolsen-Petersen, 2004). Recent data suggest a major role for TonEBP in the control of extracellular volume homeostasis by macrophages (Machnik et al., 2009). The results of our present study encouraged us to perform a set of experiments on H36.12j cells, a hybrid macrophage cell line, to evaluate the roles of TonEBP and Akt on NF-κB activation by hypertoncity in macrophages. As revealed by increased expression of TNF-α mRNA, NF-κB activity increased after 3 h of LPS (10 ng/ml) or hypertonic (400 mOsmol/kg) challenge (Figure 9, A and C), although the stimulatory effect produced by either stimulus was smaller than that observed in mpkCCDcl4 cells. Similar to mpkCCDcl4 cells, LPS did not affect AR mRNA expression (Figure 9, A and C). RNAi against TonEBP greatly reduced TonEBP expression, decreased its activity, as revealed by reduced levels of AR mRNA expression, and blunted increased TNF-α mRNA expression after hypertonic challenge (Figure 9A). Reduced TonEBP expression in macrophages decreased, but did not abolish, TNF-α mRNA expression after LPS challenge (Figure 9A). Similar to mpkCCDcl4 cells, IκBα protein expression first decreased during the first hour of hypertonic challenge then increased after longer periods of stimulation (Figure 9B). Triciribine (30 μM) abolished hypertonicity-induced IκBα degradation, dramatically reduced AR mRNA stimulation by hypertonicity (Figure 9B) and significantly reduced TNF-α mRNA stimulation by either LPS or hypertonicity (Figure 9C). Together, these data show that hypertonicity induces NF-κB activity in H36.12j cells, an event that is dependent on both TonEBP and Akt, supporting the idea that our observations made in mpkCCDcl4 cells can be extrapolated to macrophages.

Figure 9.

NF-κB activation by hypertonicity in H36.12j cells depends on TonEBP and Akt activity. (A) Left. immunoblot of protein lysates from cells transfected with RNAi against TonEBP or scrambled RNAi. The arrow depicts the band corresponding to TonEBP. Right, real-time PCR analysis of AR and TNF-α transcripts in cells transfected with RNAi against TonEBP or scrambled RNAi and exposed to LPS or hypertonic medium (NaCl). Data are represented as fold induction over nonstimulated cells transfected with scrambled RNAi (Ctl). (B) Left, immunoblot of protein lysates against IκBα or PKAc (used as a loading control) in cells challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium for various periods. Time-dependent IκBα degradation is graphically represented as fold IκBα expression in stimulated cells at each time point over nonstimulated cells. (B) Right, immunoblot of protein lysates against IκBα or PKAc (used as a loading control) in cells pre-treated or not with Akt antagonist triciribine and challenged or not (Ctl) with hypertonic medium for 30 min. IκBα protein expression is graphically represented as fold expression over control cells. (C) Real-time PCR analysis of AR and TNF-α transcripts in cells treated or not with triciribine and challenged with either LPS or hypertonic medium for 3 h. Data are represented as fold induction over nonstimulated (Ctl) cells.

DISCUSSION

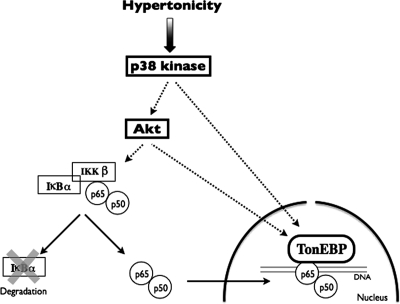

In this study, we show that increased NF-κB activity on the onset of hypertonic challenge depends on increased activities of p38 kinase, Akt, and TonEBP. As depicted in Figure 10, p38 kinase enhances TonEBP activity at least in part by stimulating Akt activity. Akt in turn increases NF-κB activity by enhancing both TonEBP activity and IκBα degradation. IκBα degradation leads to increased nuclear translocation of p65-containing NF-κB complexes. Although this event alone suffices to induce weak NF-κB activity, it notably increases the ability of hypertonicity-activated TonEBP to associate with p65, considerably enhancing NF-κB transcriptional activity.

Figure 10.

Proposed mechanism for NF-κB activation by hypertonicity. Hypertonicity activates NF-κB in a two-step process. In a first step, hypertonicity stimulates p38 kinase, which enhances the activities of both Akt and TonEBP. Increased Akt activity in turn not only contributes to enhancing TonEBP activity but also induces IκBα to dissociate from cytosolic p65. This process depends on IKKβ activity. Unconjugated IκBα is degraded allowing free p65, associated with other NF-κB binding partners such as p50, to translocate across the nuclear membrane. In a second step, TonEBP associates with p65-containing complexes bound to DNA, enhancing NF-κB transcriptional activity. NF-κB activation by hypertonicity is transient and decreases as IκBα protein expression increases in response to increased IκBα transcriptional activity.

Hypertonicity imparts massive changes on cell physiology, many of which are part of a collective effort that allows cells to adapt and survive in hypertonic environments. A critical component of this prosurvival response is the ability of the challenged cell to rapidly accumulate organic osmolytes. This allows cytoplasmic ionic strength to return to its original level, thereby preventing continual macromolecular damage. Although a fundamental interspecies event, the signaling mechanisms and nature of accumulated osmolytes vary between species. In mammalian cells, the importance of TonEBP in osmolyte accumulation is well appreciated. The effect of hypertonicity on NF-κB activity, in contrast, is less obvious. Altered NF-κB activity in response to hypertonicity has been documented in various cell types, including skin fibroblasts, monocytic cells, gastric epithelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells (Andrieu et al., 1995; Shapiro and Dinarello, 1997; Kim et al., 1999; Hattori et al., 2000; Pingle et al., 2003). In the kidney, similar to our observations made in renal principal cells (this study; Hasler et al., 2008), hypertonicity was shown to increase NF-κB activity in renal medullary interstitial cells (Hao et al., 2000). Increased NF-κB activity may represent a protective measure against hypertoncity-induced apoptosis. In this setting, our results show that TonEBP plays a dual role in protecting cells against hypertonicity by controlling classical transcriptional stimulation of TonEBP-inducible genes and by up-regulating NF-κB transcriptional activity.

In contrast to effector mechanisms mediating organic osmolyte accumulation, the signaling cascades mediating osmosensitive gene expression in mammalian cells are vague. It is becoming increasingly clear that the hypertonic response is a complex process involving the integration of multiple signals and signal transduction pathways. Our study shows that hypertonic activation of p38 kinase and downstream activation of Akt play central roles in both TonEBP activity and p65 nuclear translocation. Our data further show that this leads to increased interaction between TonEBP and NF-κB, which in turn probably enhances the osmoprotective response. What are the mechanistic implications of such an interaction? A genome-wide RNAi screen performed on Caenorhabditis elegans demonstrated that loss of function of genes encoding proteins that normally maintain levels of properly folded and functioning proteins, including those involved in protein synthesis, folding, and degradation, triggers an osmoprotective response (Lamitina et al., 2006). This offers the intriguing possibility that protein damage may function as a signal to activate osmoprotective gene expression. In this respect, an antiapoptotic response mediated by TonEBP-NF-κB interactivity would give cells time to accumulate organic osmolyes, increase protein structural stability, and decrease protein misfolding, thus allowing them to adapt to their hypertonic environment.

Osmotic stress was recently shown to partly mimic transcriptional responses to infection in C. elegans (Rohlfing et al., 2010). Notably, GATA factors elt-2 and elt-3, implicated previously in infection-induced transcriptional responses, also were found to mediate osmosensitive gene expression. Similar to GATA factors, TonEBP plays an important role in both osmoprotection and immunity by protecting osmotically challenged lymphoid tissue and stimulating cytokine transcription in T cells (Lopez-Rodriguez et al., 2001; Go et al., 2004). Because known homologues of rel-type transcription factors are not expressed in C. elegans, this functional link may have preceded TonEBP evolution. The interaction between TonEBP and NF-κB signaling shown in our study further highlights functional interactivity between osmoprotective mechanisms and immunity.

Increased NF-κB Activity by Hypertonicity: Role of TonEBP

Several observations made in the present study provide sound evidence that p65-TonEBP interactivity at κB elements constitutes a major mechanism by which hypertonicity induces NF-κB activity. 1) Changes observed for TNF-α mRNA expression were echoed not only by similar changes in MCP-1 and IκBα mRNA expression (Figure 3) but also luciferase activity, the latter of which is driven by a promoter that contains κB but not TonE elements (Figure 8B). 2) We have shown previously that increased TNF-α mRNA expression by hypertonicity is enhanced by constitutively active IKKβ and reduced by both super-repressor IκBα and RNAi against p65 (Hasler et al., 2008). This same study showed that NF-κB–driven luciferase activity by hypertonicity is abolished by super-repressor IκBα. Because NF-κB mutants have no effect on TonEBP activity (Figure 4), these results probably reflect changes in TonEBP-p65 interactivity. 3) An interaction between TonEBP and p65 is directly shown by immunoprecipitation, ChIP, and DAPA experiments (Figure 8), the latter two experiments of which also show binding of TonEBP-p65–containing complexes to κB elements.

Hypertonicity transiently increased p38 kinase, ERK, JNK, and Akt phosphorylation levels, but only p38 kinase and Akt were found to control TonEBP activity. The exact role of p38 kinase in regulating TonEBP activity in mammalian cells is subject to some debate. Although data of some studies indicate that p38 kinase plays no role (Kwon et al., 1995; Kultz et al., 1997), other pieces of evidence suggest that p38 kinase helps activate TonEBP by targeting the TonEBP transactivation domain, although it is not clear whether this involves direct phosphorylation of TonEBP by p38 kinase itself (Ko et al., 2002; Kuper et al., 2009). Other signaling pathways in addition to p38 kinase regulate TonEBP activity (Burg et al., 2007; Kwon et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2010). Of special interest to this study, PI3-kinase was shown previously to enhance TonEBP activity under hypertonic conditions (Irarrazabal et al., 2004). This event was found to occur independently of p38 kinase but did depend on ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein kinase activation (Irarrazabal et al., 2006), possibly by affecting TonEBP phosphorylation and its ensuing transactivation. EGFR signaling was recently found to stimulate TonEBP transcriptional activity during osmotic stress, although the authors did not investigate a role played by Akt (Kuper et al., 2009). Results of the present study (Figure 6) strongly suggest a role for Akt in controlling TonEBP activity. They also indicate that TonEBP activity is regulated by p38 kinase, not only via downstream phosphorylation of Akt but also via an Akt-independent mechanism.

TonEBP activity varies according to environmental tonicity. Although partly active under isotonic conditions, a rise or fall of environmental tonicity enhances and reduces, respectively, its activity (Kwon et al., 2009). Our data show that although TonEBP controls NF-κB activation by hypertonicity, it only plays a marginal role in NF-κB activation by LPS or TNF-α (Figures 3 and 8). Nuclear translocation of NF-κB complexes is increased in response to LPS, TNF-α, and hypertonic challenge. TonEBP activity, in contrast, is increased only by hypertonicity, not by LPS or TNF-α. These results strongly indicate that changes of NF-κB activity that follow changes of environmental tonicity directly reflect TonEBP activity levels. Our data further indicate that TonEBP does not affect IκBα degradation (Figure 7) and that both increased TonEBP activity and p65 nuclear translocation contribute to enhancing NF-κB activity on the onset of hypertonic challenge. As stated, in addition to binding to TonE elements of NF-κB-sensitive genes, when present, TonEBP exerts its effects via NF-κB transactivation by binding to a p65-containing complex at κB elements (Figure 8).

The physiological importance of modulated NF-κB transactivation has been demonstrated by the roles of various molecules that regulate NF-κB transcriptional activity, such as NF-κB coactivator CBP/p300, glycogen synthase kinase-3β, and T2K (Zhong et al., 1997; Bonnard et al., 2000; Hoeflich et al., 2000). Several studies have shown that activator protein (AP)-1 alters NF-κB activity by physically interacting with it (Stein et al., 1993; Thomas et al., 1997; Li et al., 2000; Xiao et al., 2004). c-Fos and c-Jun physically interact with p65 through its Rel homology domain (Stein et al., 1993). Although conflicting reports have been made on the subject, Irarrazabal et al. (2008) provide evidence that AP-1 enhances TonEBP-dependent gene transcription by physically associating with it at its DNA binding site. Results of that study indicate that c-Fos and c-Jun physically associate with a region located near amino acid 547 of TonEBP, i.e., near the Rel homology domain. Data depicted in Figure 2C tentatively suggest competitive binding between p65 and AP-1 for Rel homology domains. It is tempting to speculate that hypertonic challenge facilitates either direct or indirect binding between DNA-bound p65 and TonEBP via dissociation of AP-1 from both p65 and TonEBP.

Increased NF-κB Activity by Hypertonicity: Role of Akt

Our previous results (Hasler et al., 2008) as well as those of the present study collectively show that the stimulatory effect of hypertonicity on NF-κB activity is mediated not only by TonEBP but by TonEBP-independent IκBα degradation. Hypertonic activation of Akt was found to play a key role in this process. Hence, under hypertonic conditions Akt mediates both TonEBP activity and IκBα degradation.

Previous data have shown that HRG-β1-activation of p38 kinase enhances NF-κB activity by modulating IκBα phosphorylation and p65 nuclear translocation (Tsai et al., 2003). MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) has moreover been shown to repress NF-κB–dependent transcription (King et al., 2009). Our data link p38 kinase to downstream Akt activation under hypertonic conditions. Akt signaling has been extensively studied and is associated with many human malignancies, reflecting the involvement of Akt in numerous processes, including cell proliferation and apoptosis (Nicholson and Anderson, 2002). Whereas it is well established that Akt is integrated into the activation process of NF-κB, the exact mechanism by which this is achieved varies between studies. Akt-mediated phosphorylation of Cot/Tp12 (a member of the MAP3K family) after T-cell receptor stimulation has been shown to trigger IKK activity (Kane et al., 2002). In another study, IKK activation by platelet-derived growth factor in fibroblasts was found to depend on transient, PI3-kinase–dependent, association among Akt, IKKα, and IKKβ (Romashkova and Makarov, 1999). Similarly, Akt was found to be necessary for IKK activation by TNF-α in embryonic kidney 293 cells, an event that depends on intact PI3-kinase activity and that is partly mediated by an association between Akt and IKKα (Ozes et al., 1999). In addition to activating the classical pathway, Akt may directly phosphorylate p65, although contrasting results have been reported (Madrid et al., 2000; Kane et al., 2002).

We have shown previously that RNAi against p65 reduce the enhancing effect of hypertonicity on NF-κB activity (Hasler et al., 2008). We show here (Figures 1 and 7, A, C, and D) that the effect of hypertonicity relies on elements of the canonical NF-κB pathway. Our data further show that hypertonicity-induced NF-κB activation relies on increased Akt activity (Figures 5, D and E, 6C, and 7D). It is worthwhile pointing out that although Akt phosphorylation by TGF-α was similar to that induced by hypertonicity the extent of IκBα degradation by TGF-α was greater than that achieved by hypertonicity. Also, Akt pharmacological inhibition alone decreased TNF-α mRNA expression twofold under isotonic conditions (data not shown). Nonetheless, the effect of hypertonicity on NF-κB transcriptional activity was ∼10-fold greater than that of TGF-α further, indicating that the effects of hypertonicity on NF-κB activity do not rely on increased Akt activity alone.

Unexpectedly, we found that IκBα mRNA expression was unaffected by TGF-α challenge and that its stimulation by hypertonicity was not reduced by inhibition of either p38 kinase, TGFR, PI3-kinase, or Akt (Supplemental Figures S3–S5), clearly indicating that unlike TNF-α and MCP-1 mRNA, hypertonicity stimulates IκBα mRNA expression independently of both p38 kinase and Akt. In contrast, a role for TonEBP in regulating IκBα expression by hypertonicity is confirmed in Figures 3 and 8. Possibly, this discrepancy may reflect differences between regulatory components bound to TNF-α and MCP-1 promoters and those bound to the IκBα promoter.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Michelangelo Foti and Manlio Vinciguerra (Department of Cellular Physiology and Metabolism, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland) for having prepared HepG2 cells. This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grant 3100A0_122559/1 and grants from the Fondation Novartis pour la Recherche en Sciences Médico-Biologique and Fondation Schmidheiny (to U. H.) and National Institutes of Health grant DK-42479 to (H.M.K.).

Abbreviations used:

- AR

aldose reductase

- BGT1

sodium-chloride-betaine cotransporter

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DAPA

DNA affinity purification analysis

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- SMIT

sodium-myo-inositol cotransporter

- TonEBP

tonicity-responsive binding-protein.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0133) on August 4, 2010.

REFERENCES

- Andrieu N., Salvayre R., Jaffrezou J. P., Levade T. Low temperatures and hypertonicity do not block cytokine-induced stimulation of the sphingomyelin pathway but inhibit nuclear factor-kappa B activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:24518–24524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D. K., Iglehart J. D. Linkage between EGFR family receptors and nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) signaling in breast cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;209:645–652. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnard M., et al. Deficiency of T2K leads to apoptotic liver degeneration and impaired NF-kappaB-dependent gene transcription. EMBO J. 2000;19:4976–4985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.18.4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg M., Ferraris J., Dmitrieva N. Cellular response to hypertonic stress. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:1441–1474. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00056.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canono B. P., Campbell P. A. Production of mouse inflammatory macrophage hybridomas. J. Tissue Cult. Methods. 1992;14:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Citri A., Yarden Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:505–516. doi: 10.1038/nrm1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W. G., Zhu Y., Montero A., Wu K. K. Quantitative analysis of binding of transcription factor complex to biotinylated DNA probe by a streptavidin-agarose pulldown assay. Anal. Biochem. 2003;323:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esensten J. H., Tsytsykova A. V., Lopez-Rodriguez C., Ligeiro F. A., Rao A., Goldfeld A. E. NFAT5 binds to the TNF promoter distinctly from NFATp, c, 3 and 4, and activates TNF transcription during hypertonic stress alone. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3845–3854. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T., Nolan G. P., Liou H. C., Scott M. L., Baltimore D. The candidate proto-oncogene bcl-3 encodes a transcriptional coactivator that activates through NF-kappa B p50 homodimers. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1354–1363. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaeggeler H. P., Gonzalez-Rodriguez E., Jaeger N. F., Loffing-Cueni D., Norregaard R., Loffing J., Horisberger J. D., Rossier B. C. Mineralocorticoid versus glucocorticoid receptor occupancy mediating aldosterone-stimulated sodium transport in a novel renal cell line. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005;16:878–891. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go W. Y., Liu X., Roti M. A., Liu F., Ho S. N. NFAT5/TonEBP mutant mice define osmotic stress as a critical feature of the lymphoid microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10673–10678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403139101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I., Dolga A. M., Nijholt I. M., van Dijk G., Eisel U. L. Inflammation and NF-kappaB in Alzheimer's disease and diabetes. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:809–821. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gum R. J., McLaughlin M. M., Kumar S., Wang Z., Bower M. J., Lee J. C., Adams J. L., Livi G. P., Goldsmith E. J., Young P. R. Acquisition of sensitivity of stress-activated protein kinases to the p38 inhibitor, SB 203580, by alteration of one or more amino acids within the ATP binding pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15605–15610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao C. M., Yull F., Blackwell T., Komhoff M., Davis L. S., Breyer M. D. Dehydration activates an NF-kappaB-driven, COX2-dependent survival mechanism in renal medullary interstitial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:973–982. doi: 10.1172/JCI9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S., Zhao H., Darzynkiewicz Z., Battula S., Ferreri N. R. Expression and function of NFAT5 in medullary thick ascending limb (mTAL) cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1494–F1503. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90436.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler U., Jeon U. S., Kim J. A., Mordasini D., Kwon H. M., Feraille E., Martin P. Y. Tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein is an essential regulator of aquaporin-2 expression in renal collecting duct principal cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006a;17:1521–1531. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler U., Leroy V., Jeon U. S., Bouley R., Dimitrov M., Kim J. A., Brown D., Kwon H. M., Martin P. Y., Feraille E. NF-kappa B modulates aquaporin-2 transcription in renal collecting duct principal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:28095–28105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708350200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler U., Nielsen S., Feraille E., Martin P. Y. Posttranscriptional control of aquaporin-2 abundance by vasopressin in renal collecting duct principal cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2006b;290:F177–F187. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00056.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler U., Vinciguerra M., Vandewalle A., Martin P.-Y., Feraille E. Dual effects of hypertonicity on aquaporin-2 expression in cultured renal collecting duct principal cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005;16:1571–1582. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004110930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y., Hattori S., Sato N., Kasai K. High-glucose-induced nuclear factor kappaB activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000;46:188–197. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeflich K. P., Luo J., Rubie E. A., Tsao M. S., Jin O., Woodgett J. R. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cell survival and NF-kappaB activation. Nature. 2000;406:86–90. doi: 10.1038/35017574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irarrazabal C. E., Burg M. B., Ward S. G., Ferraris J. D. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediates activation of ATM by high NaCl and by ionizing radiation: role in osmoprotective transcriptional regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8882–8887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602911103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irarrazabal C. E., Liu J. C., Burg M. B., Ferraris J. D. ATM, a DNA damage-inducible kinase, contributes to activation by high NaCl of the transcription factor TonEBP/OREBP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8809–8814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403062101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irarrazabal C. E., Williams C. K., Ely M. A., Birrer M. J., Garcia-Perez A., Burg M. B., Ferraris J. D. Activator protein-1 contributes to high NaCl-induced increase in tonicity-responsive enhancer/osmotic response element-binding protein transactivating activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:2554–2563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane L. P., Mollenauer M. N., Xu Z., Turck C. W., Weiss A. Akt-dependent phosphorylation specifically regulates Cot induction of NF-kappa B-dependent transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:5962–5974. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5962-5974.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Seo J. Y., Kim K. H. Effects of mannitol and dimethylthiourea on Helicobacter pylori-induced IL-8 production in gastric epithelial cells. Pharmacology. 1999;59:201–211. doi: 10.1159/000028321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King E. M., Holden N. S., Gong W., Rider C. F., Newton R. Inhibition of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription by MKP-1, transcriptional repression by glucocorticoids occurring via p38 MAPK. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:26803–26815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.028381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko B. C., Lam A. K., Kapus A., Fan L., Chung S. K., Chung S. S. Fyn and p38 signaling are both required for maximal hypertonic activation of the osmotic response element-binding protein/tonicity-responsive enhancer-binding protein (OREBP/TonEBP) J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:46085–46092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolsen-Petersen J. A. Immune effect of hypertonic saline: fact or fiction? Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2004;48:667–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kultz D., Garcia-Perez A., Ferraris J. D., Burg M. B. Distinct regulation of osmoprotective genes in yeast and mammals. Aldose reductase osmotic response element is induced independent of p38 and stress-activated protein kinase/Jun N-terminal kinase in rabbit kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13165–13170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper C., Steinert D., Fraek M. L., Beck F. X., Neuhofer W. EGF receptor signaling is involved in expression of osmoprotective TonEBP target gene aldose reductase under hypertonic conditions. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1100–F1108. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90402.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H. M., Itoh T., Rim J. S., Handler J. S. The MAP kinase cascade is not essential for transcriptional stimulation of osmolyte transporter genes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;213:975–979. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M. S., Lim S. W., Kwon H. M. Hypertonic stress in the kidney: a necessary evil. Physiology. 2009;24:186–191. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00005.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamitina T., Huang C. G., Strange K. Genome-wide RNAi screening identifies protein damage as a regulator of osmoprotective gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12173–12178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602987103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Kim M., Im Y. S., Choi W., Byeon S. H., Lee H. K. NFAT5 induction and its role in hyperosmolar stressed human limbal epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49:1827–1835. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]