Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced in the neuronal, renal and vascular systems not only influence cardiovascular physiology, but are also strongly implicated in pathological signaling leading to hypertension. Different sources of ROS have been identified, ranging from xanthine-xanthine oxidase and mitochondria to NADPH oxidase (Nox) enzymes. Out of seven Nox family members, Nox1, Nox2, Nox4 (and Nox5 in humans) influence the cardiovascular system. Their activation processes, cell and tissue distribution vary widely, adding complexity to understanding their functional roles. Whether these systems act collectively or independently in disease conditions is unclear, but recently, feed forward mechanisms have been established between ROS sources. Studies published in Hypertension over the last few years are the focus of this review and they provide a framework with which to consider the roles of Nox enzymes in neuronal, renal and vascular hypertensive mechanisms, as well as cardiac remodeling, and their relationships with other ROS-generating systems.

Neuronal ROS in hypertension

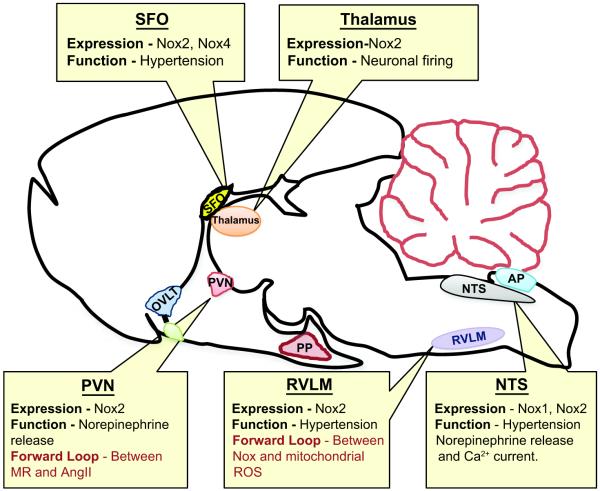

Redox signaling in the central nervous system (CNS) is well recognized in neuronal control of blood pressure (BP) as well as in response to Angiotensin II (AngII) and aldosterone, which are linked to ROS-dependent hypertension. Recently, new roles for ROS have been described in the hypothalamus and brain stem, nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), subfornical organ (SFO), rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), and area postrema (AP) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Neuronal NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS involved in central regulation of hypertension.

NADPH oxidase homologues, mainly Nox2 and Nox4, are found in different regions of the neuronal system and are reported to have a role in the neuropathogenesis of hypertension by enhancing the sympathetic nerve activity. Nox-induced ROS initiate a forward loop (1) in cross activation of different receptors and (2) between Nox and mitochondrial ROS. SFO, subfornical organ; OVLT, organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; PP, posterior pituitary; AP, area postrema; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; RVLM, rostral ventrolateral medulla.

Several studies suggest that Nox are a primary source of superoxide (O2.−) in AngII-induced neuronal activity. In primary neuronal cultures from the hypothalamus and brain stem, losartan, an angiotensin type1 receptor (AT1R) antagonist, gp91 ds-tat, a peptide inhibitor of Nox2, and Tempol, a superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic, attenuate AngII-induced ROS production and reduce neuronal firing rate.1 Hypothalamic Nox is also implicated in norepinephrine secretion2 and renal sympathetic nerve activity3 of phenol-induced renal injury and Dahl salt-sensitive (DHSS) hypertensive rat models. NADPH oxidase activity and expression of Nox2, as well as its subunits p22phox and p47phox, increase in these animals, and this, as well as BP, is reversed by treatment with Tempol, polyethylene glycolated SOD (PEG-SOD) or the nonspecific Nox inhibitor, diphenylene iodonium (DPI).2, 3

Systemic AngII infusion induces hypertension by increasing O2.− in the SFO, a primary brain sensor for blood-borne AngII. Lob et al4 reported that selective deletion of SOD3 in the SFO specifically increases AngII-induced vascular T-cell and leukocyte infiltration in addition to increasing sympathetic modulation of heart rate, BP, and vascular O2.−. These observations suggest that ROS in the CNS influence peripheral organs in hypertension. Such effects seem to be specific for individual Nox homologues. Peterson et al5 showed that Nox2 and Nox4 mediate AngII-mediated ROS production in the SFO, but although both are necessary for the vasopressor response to AngII, only Nox2 participates in the dipsogenic response.5

In rats subjected to coronary artery ligation, four-week intracerbroventricular (ICV) infusion of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonist RU28318 reduces AT1R, p47phox and Nox2 expression, as well as Nox-dependent ROS, in the PVN with a concomitant reduction in plasma norepinephrine levels.6 This study suggests that cross talk exists between MR and AngII ROS-dependent signaling in the PVN (Figure 1).6

ROS signaling to hypertension is also implicated in the NTS. Compared to Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats, stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) exhibit elevated activity of Rac1, a regulator of Nox1 and Nox2, in the NTS, and adenoviral-mediated inhibition of Rac1 or expression of CuZnSOD decreases BP, heart rate and urinary norepinephrine excretion.7 Additionally, in the dorsomedial NTS (dmNTS), AngII stimulates Nox activity and modulates Ca2+ current, a response that is blocked by gp91 ds-tat and apocynin, a Nox subunit assembly inhibitor.8 Moreover, in dmNTS neurons of mice lacking Nox2, AngII fails to elevate ROS or to potentiate L-type Ca2+ current.8

Short-term infusion of AngII elevates BP, heart rate, and renal sympathetic nerve activity in parallel with upregulated expression of Nox2, p22phox p47phox and p67phox in the RVLM9, a brain stem site that maintains sympathetic vasomotor tone. Additionally, in SHR and AngII-infused WKY rats, mitochondrial dysfunction in the RVLM and the subsequent production of mitochondrial-localized ROS play a critical role in cardiovascular pathology.10 Coenzyme Q10 treatment restores electron transport capacity and reduces BP and sympathetic neurogenic vasomotor tone. Interestingly, p22phox antisense, MnSOD and catalase prevent AngII-dependent ROS generation, suggesting the existence of a feed forward effect of Nox on mitochondrial function (Figure 1).10

Renal ROS in hypertension

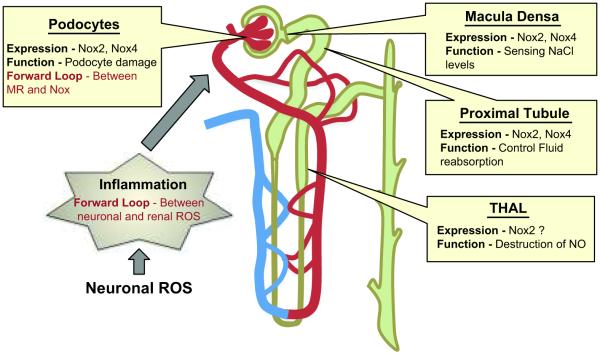

The kidney regulates blood pressure by controlling water and electrolyte balance and secreting hormones, including AngII. Several studies implicate ROS, and in particular Nox enzymes, in multiple kidney functions whose dysregulation can contribute to hypertension and in the end-organ damage that accompanies hypertension (Figure 2).11-14 For example, coinfusion of UK14,304, an α2-adrenoceptor agonist enhances intrarenal AngII infusion-induced renal vascular resistance, an effect abolished by Tempol, gp91ds-tat, and DPI15. In macula densa (MD) cells, which sense luminal NaCl and control afferent arteriolar tone in a ROS-dependent manner as part of the tubuloglomerular feedback process, Nox2 is responsible for salt-induced changes in O2.− generation and Nox4 regulates basal ROS.16 The precise mechanism of Nox2 activation is unclear; however, different possibilities include alterations in the intracellular pH and depolarization of the MD.17 In human renal proximal tubule cells, the dopamine-1 receptor agonist fenoldopam inhibits, whereas disruption of lipid rafts and AngII stimulates, Nox2 and Nox4.18 Moreover, impaired proximal tubule fluid reabsorption in SHR, is reversed by apocynin and p22phox downregulation,19 and an increase in Nox-dependent ROS abolishes the inhibitory effect of AngII on Na/K-ATPase (NKA), which may contribute to increased sodium reabsorption and hypertension in rats treated with the oxidant L-buthionine sulfoximine (BSO).20

Figure 2. Renal NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS involved in functional alterations of the kidney in hypertension.

NADPH oxidase homologues, mainly Nox2 and Nox4, are expressed in different regions of the renal system and regulate normal kidney function and end organ damage in hypertension. Similar to neuronal ROS, Nox-induced ROS initiate a forward loop in (1) cross activation of different receptors in podocytes and (2) cross-talk between organ systems like central ROS-induced renal inflammation. THAL, thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle.

In the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (THAL), nitric oxide (NO) - induced reduction of NaCl absorption can be counter-regulated by Nox-dependent, O2.−-mediated destruction of NO.21 Nox-dependent ROS production in THAL is observed in streptozotocin treated rats,22 SD rats treated with AngII,23 and salt treated DHSS rats.24 The importance of NO and O2.− interactions is further strengthened by the observation that co-infusion of L-arginine (to increase NO bioavailability) blunts AngII-induced hypertension and associated renal damage.25 Interestingly, cellular stretch26 and H+ efflux27 stimulate O2.− in the medullar THAL.

As noted, Nox is also linked to renal damage.12 In aldosterone-induced damage to podocytes, which constitute the final glomerular filtration barrier, increased Nox activity and upregulation of Nox2, p22phox and p47phox were reported.28 Moreover, upregulation of Nox2 and p22phox in glomeruli is associated with salt-induced podocyte damage in DHSS rats,29 and inhibition of Nox activity improves podocyte function. Transgenic TG(mRen2)27 (Ren2) rats treated with rosuvastatin, a 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitor that effectively reduces AngII-mediated Nox activity and Nox2, Nox4, Rac, and p22phox expression in podocytes, exhibit reduced periarteriolar fibrosis and podocyte footprocess effacement along with reduced systolic BP, albuminuria and renal Nox activity.30 AngII infusion also causes renal damage by inducing inflammation. In CCR2−/− mice, which lack the receptor for monocyte chemotactic protein-1, AngII-induced renal damage characterized by macrophage infiltration and albuminuria is significantly reduced independent of hypertension.31 Interestingly, in CCR2+/+ mice, AngII infusion increases Nox2 expression and 3-Nitrotyrosine staining, an effect that is significantly less in CCR2−/− mice, indicating a role for Nox-dependent ROS in renal inflammation and damage.31 Different approaches targeting Nox are beneficial in preventing renal damage. In DHSS rats, kallistatin, a serine protease inhibitor, effectively prevents high-salt induced Nox-dependent O2.− formation and renal damage by improving NO levels and eNOS expression.32 Similarly, kidney-specific expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) prevents AngII-dependent hypertension,33 which could be explained by a possible influence of HO-1 end products on Nox function.34

Cross talk between MR and Nox-dependent ROS also exists in renal hypertension. In SHR/cp rats, a model of metabolic syndrome, salt-induced renal damage and hypertension, Tempol treatment blocks MR expression, elevated proteinurea and renal abnormalities, suggesting a role for ROS in MR activation.35 Interestingly, Nox-dependent ROS production is also a consequence of MR activation in DHSS rats.29 MR inhibition prevents Nox subunit upregulation in both the kidney and left ventricle in uremia, indicating a role for Nox in MR signaling.36 These observations clearly suggest a feed-forward mechanism between MR and Nox-dependent ROS.

Vascular ROS in hypertension

Superoxide induces vascular dysfunction in hypertension by its well-described interaction with NO. New animal studies support this concept, showing that high salt intake along with BSO treatment causes vascular dysfunction by reducing NO levels and eNOS activity in rats.37 Similarly, AngII-induced ROS cause vascular contractions in WKY mesenteric arteries that are reversed by atorvastatin treatment, possibly via inhibition of Nox1-induced ROS.38 A link to human disease was established by Lavi et al,39 who showed that local oxidative stress reduces NO bioavailability in humans with coronary endothelial dysfunction.

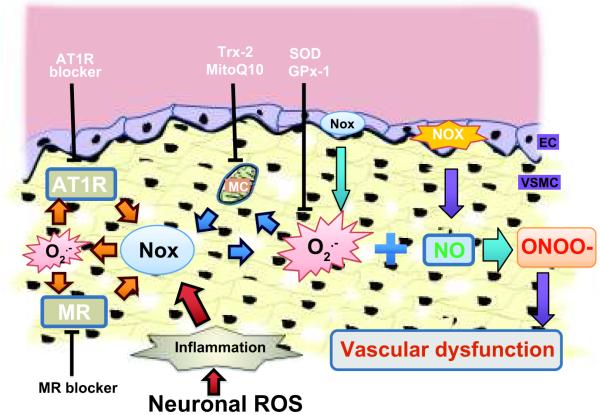

The importance of effective antioxidant systems in the vasculature to limit excessive O2.− and prevent hypertension is only beginning to be appreciated (Figure 3). In SOD3 knockout animals, AngII infusion increases O2.− and reduces endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in small mesenteric arterioles.40 Qin et al41 demonstrated that in mice bearing a mutation in the copper transporter Menkes ATPase (MNK), SOD3 activity is reduced because of impaired incorporation of copper, leading to impaired ACh-induced endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and further supporting a role for SOD3 in vascular protection. Moreover, deletion of glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx-1), an enzyme that metabolizes H2O2 to water, augments AngII-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation.42 Conversely, overexpression of human thioredoxin-2, a mitochondrial-specific antioxidant enzyme, attenuates AngII induction of O2.−, H2O2 and mitochondrial O2.−, and significantly reduces Nox2, p47phox and Rac expression.43

Figure 3. Vascular NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS and vascular function.

NADPH oxidases play an important role in normal vascular signaling and vascular dysfunction. Endothelial and vascular smooth muscle Nox-derived ROS inactivate NO and initiate a forward loop (1) in cross activation of different receptors (orange arrows), (2) between ROS sources (blue arrows), and (3) in cross-talk between organ systems like central ROS induced vascular inflammation (red arrows). AT1R, Angiotensin type 1 receptors; MR, mineralocorticoid receptors; Nox, NADPH oxidases; MC, mitochondria; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; ONOO-, peroxynitrite; EC, endothelial cells; VSMC, Vascular smooth muscle cells; Trx, thioredoxin 2; MitoQ10, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant; SOD3, superoxide dismutase-3; Gpx-1, glutathione peroxidase-1.

Much of the work linking ROS to hypertension was performed in animal models with elevated or altered AngII; however, recent studies have implicated MR-induced ROS as well (Figure 3). Savoia et al44 showed that the MR blocker, eplerenone, significantly reduces arterial wall stiffness, medial collagen/elastin ratio and circulating inflammatory mediators in hypertensive patients. Another MR blocker, spironolactone, protects Ren2 rats from vascular apoptosis and structural injury via Nox-dependent ROS inhibition.45 In contrast, in endothelial cells, aldosterone treatment increases ROS generation by translocating p47phox to the membrane from the cytosol.46 Eplerenone or knockdown of p47phox reverses the reduced NO levels and the reduction in eNOS Ser 1177 phosphorylation.46 Likewise, eplerenone pretreatment ameliorates aortic endothelial dysfunction observed one week following myocardial infarction in rats, in part due to normalization of NO bioavailability by reduction in p22phox expression and aortic ROS generation, and restoration of eNOS phosphorylation.47

An additional mechanism linking AngII to elevated ROS is Nox-mediated activation of mitochondrial ROS production (Figure 3). Similar to the CNS, AngII-induced Nox activation increases mitochondrial ROS production in aortic endothelial cells.48 Interestingly, the mitochondrial targeted antioxidant, MitoQ10, reduces systolic blood pressure and improves NO bioavailability in thoracic aorta of SHR.49 These studies suggest the existence of a feed forward loop between two important ROS sources within the same cells.

Recently, a role for T-cells in AngII-induced hypertension was proposed.50 AngII induces T-cell activity, proinflammatory cytokine production and infiltration in perivascular fat. AT1R expression in immune cells has been shown to be involved in AngII-induced hypertension.51 As noted, deletion of SOD3 in the CVO can increase T-cell activation, leading to increased AngII-induced vascular O2.− production and vascular inflammation due to T-cell and leukocyte infiltration, and suggesting that a feed-forward loop exists between organ systems.4

Cardiac ROS in hypertension

One of the deleterious effects of hypertension is hypertrophy or thickening of heart muscle. Similar to the CVS, renal and vascular systems, different ROS sources participate in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling,52 and different antioxidant systems play an important role in reducing hypertrophic conditions. For example, Gpx-1 prevents cardiac hypertrophy in AngII-dependent hypertension. Glutathione peroxidase-1 knockout mice exhibit accelerated cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction.53 Carbon monoxide, one of the end products of HO-1, inhibits AngII-induced left ventricular hypertrophy by reducing the expression of p47phox, p67phox and ROS generation.54 Interestingly, it was also reported that inhibition of mitochondrial ROS by MitoQ treatment reduces hypertrophy in stroke-prone SHR rats.49

Cross talk between AngII and MR is also observed in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. In transgenic mice with conditional, cardiomyocyte-restricted overexpression of the human MR, AngII infusion causes a greater increase in left ventricle mass/body weight than in wild type mice.55 These effects are associated with increased expression of hypertrophic markers (collagen and fibronectin) and Nox2.55 Similarly, in uremic rats, spironolactone attenuates left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac O2.− production, and Nox2, Nox4 and p47phox expression, which indicates a direct role of MR in cardiac hypertrophy.36 Thus, similar to other organs, there exists an interplay between the MR and AngII systems in cardiac hypertrophy.

Summary

One concept that emerges from the recent Hypertension papers reviewed here is the existence of ROS-induced feed forward loops in the cardiovascular system. This notion adds more complexity to cardiovascular ROS signaling, but at the same time helps to improve our understanding of the multiple roles of ROS in cardiovascular pathology. There appear to be three different loops: (1) cross-activation of different receptors; (2) activation of one ROS source by another; and (3) cross-talk between organ systems. More specifically, a feed forward loop exists between AngII and MR systems. Activation of one system, AngII for example, can lead to indirect activation of the other (e.g., MR), and vice versa. Thus, specific receptor blockers of AT1R or MR prevent the subsequent activation of the MR or AT1R, respectively. With respect to ROS-induced ROS generation, a feed forward loop occurs between Nox and mitochondria in both the neuronal and vascular systems. Last but not least, stimulation of ROS signals in one organ can trigger ROS generation in other organs, as when the central alteration of O2.− levels induces vascular inflammation.

Uncovering the role of Nox in hypertension is complicated by the fact that many Nox enzymes also play important roles in normal physiology. Dissecting these roles is limited by the lack of availability of good antibodies, sufficient genetic models for individual Nox homologues, and specific Nox inhibitors. Moreover, recent studies from Touyz’s group showed that in the presence of chronic upregulation of the renin-angiotensin system, deletion of either Nox1 or Nox2 does not prevent development of hypertension.12, 56 In the face of only modest beneficial effects of antioxidants on human hypertension, the data summarized here suggest that targeting specific Nox enzymes may be beneficial more to suppress end-organ damage than to regulate BP per se. None-the-less, these recent studies strongly support a role of ROS in the pathogenesis of hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL38206, HL092120 and HL095070.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Griendling holds a patent on “Novel Mitogenic Regulators” that includes Nox1.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sun C, Sellers KW, Sumners C, Raizada MK. NAD(P)H Oxidase Inhibition Attenuates Neuronal Chronotropic Actions of Angiotensin II. Circ Res. 2005;96:659–666. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161257.02571.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye S, Zhong H, Campese VM. Oxidative Stress Mediates the Stimulation of Sympathetic Nerve Activity in the Phenol Renal Injury Model of Hypertension. Hypertension. 2006;48:309–315. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000231307.69761.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujita M, Ando K, Nagae A, Fujita T. Sympathoexcitation by Oxidative Stress in the Brain Mediates Arterial Pressure Elevation in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;50:360–367. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.091009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lob HE, Marvar PJ, Guzik TJ, Sharma S, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Induction of Hypertension and Peripheral Inflammation by Reduction of Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase in the Central Nervous System. Hypertension. 2010;55:277–283. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.142646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson JR, Burmeister MA, Tian X, Zhou Y, Guruju MR, Stupinski JA, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Genetic Silencing of Nox2 and Nox4 Reveals Differential Roles of These NADPH Oxidase Homologues in the Vasopressor and Dipsogenic Effects of Brain Angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2009;54:1106–1114. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu Y, Wei SG, Zhang ZH, Gomez-Sanchez E, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Does aldosterone upregulate the brain renin-angiotensin system in rats with heart failure? Hypertension. 2008;51:727–733. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozoe M, Hirooka Y, Koga Y, Sagara Y, Kishi T, Engelhardt JF, Sunagawa K. Inhibition of Rac1-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species in Nucleus Tractus Solitarius Decreases Blood Pressure and Heart Rate in Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Hypertension. 2007;50:62–68. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, Anrather J, Glass MJ, Tarsitano MJ, Zhou P, Frys KA, Pickel VM, Iadecola C. Nox2, Ca2+, and Protein Kinase C Play a Role in Angiotensin II-Induced Free Radical Production in Nucleus Tractus Solitarius. Hypertension. 2006;48:482–489. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000236647.55200.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao L, Wang W, Li YL, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Sympathoexcitation by central ANG II: roles for AT1 receptor upregulation and NAD(P)H oxidase in RVLM. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2271–2279. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00949.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan SH, Wu KL, Chang AY, Tai MH, Chan JY. Oxidative impairment of mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes in rostral ventrolateral medulla contributes to neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;53:217–227. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou AP, Li N, Cowley AW., Jr. Production and actions of superoxide in the renal medulla. Hypertension. 2001;37:547–553. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yogi A, Mercure C, Touyz J, Callera GE, Montezano ACI, Aranha AB, Tostes RC, Reudelhuber T, Touyz RM. Renal Redox-Sensitive Signaling, but Not Blood Pressure, Is Attenuated by Nox1 Knockout in Angiotensin II-Dependent Chronic Hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51:500–506. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chabrashvili T, Tojo A, Onozato ML, Kitiyakara C, Quinn MT, Fujita T, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Expression and cellular localization of classic NADPH oxidase subunits in the spontaneously hypertensive rat kidney. Hypertension. 2002;39:269–274. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill P, Wilcox C. NADPH oxidases in the kidney. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2006;8:1597–1607. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson EK, Gillespie DG, Zhu C, Ren J, Zacharia LC, Mi Z. Alpha2-adrenoceptors enhance angiotensin II-induced renal vasoconstriction: role for NADPH oxidase and RhoA. Hypertension. 2008;51:719–726. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.096297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang R, Harding P, Garvin JL, Juncos R, Peterson E, Juncos LA, Liu R. Isoforms and functions of NAD(P)H oxidase at the macula densa. Hypertension. 2009;53:556–563. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlstrom M, Persson AEG. Important Role of NAD(P)H Oxidase 2 in the Regulation of the Tubuloglomerular Feedback. Hypertension. 2009;53:456–457. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.125575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han W, Li H, Villar VA, Pascua AM, Dajani MI, Wang X, Natarajan A, Quinn MT, Felder RA, Jose PA, Yu P. Lipid rafts keep NADPH oxidase in the inactive state in human renal proximal tubule cells. Hypertension. 2008;51:481–487. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panico C, Luo Z, Damiano S, Artigiano F, Gill P, Welch WJ. Renal Proximal Tubular Reabsorption Is Reduced In Adult Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats: Roles of Superoxide and Na+/H+ Exchanger 3. Hypertension. 2009;54:1291–1297. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banday AA, Lokhandwala MF. Loss of Biphasic Effect on Na/K-ATPase Activity by Angiotensin II Involves Defective Angiotensin Type 1 Receptor-Nitric Oxide Signaling. Hypertension. 2008;52:1099–1105. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.117911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori T, Cowley AW., Jr. Angiotensin II-NAD(P)H oxidase-stimulated superoxide modifies tubulovascular nitric oxide cross-talk in renal outer medulla. Hypertension. 2003;42:588–593. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000091821.39824.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J, Lane PH, Pollock JS, Carmines PK. Protein Kinase C-Dependent NAD(P)H Oxidase Activation Induced by Type 1 Diabetes in Renal Medullary Thick Ascending Limb. Hypertension. 2010;55:468–473. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori T, O’Connor PM, Abe M, Cowley AW., Jr. Enhanced Superoxide Production in Renal Outer Medulla of Dahl Salt-Sensitive Rats Reduces Nitric Oxide Tubular-Vascular Cross-Talk. Hypertension. 2007;49:1336–1341. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.085811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor NE, Glocka P, Liang M, Cowley AW., Jr. NADPH oxidase in the renal medulla causes oxidative stress and contributes to salt-sensitive hypertension in Dahl S rats. Hypertension. 2006;47:692–698. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000203161.02046.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajapakse NW, De Miguel C, Das S, Mattson DL. Exogenous L-Arginine Ameliorates Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension and Renal Damage in Rats. Hypertension. 2008;52:1084–1090. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garvin JL, Hong NJ. Cellular stretch increases superoxide production in the thick ascending limb. Hypertension. 2008;51:488–493. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.102228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connor PM, Lu L, Liang M, Cowley AW., Jr. A novel amiloride-sensitive h+ transport pathway mediates enhanced superoxide production in thick ascending limb of salt-sensitive rats, not na+/h+ exchange. Hypertension. 2009;54:248–254. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shibata S, Nagase M, Yoshida S, Kawachi H, Fujita T. Podocyte as the Target for Aldosterone: Roles of Oxidative Stress and Sgk1. Hypertension. 2007;49:355–364. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000255636.11931.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagase M, Shibata S, Yoshida S, Nagase T, Gotoda T, Fujita T. Podocyte injury underlies the glomerulopathy of Dahl salt-hypertensive rats and is reversed by aldosterone blocker. Hypertension. 2006;47:1084–1093. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000222003.28517.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whaley-Connell A, Habibi J, Nistala R, Cooper SA, Karuparthi PR, Hayden MR, Rehmer N, DeMarco VG, Andresen BT, Wei Y, Ferrario C, Sowers JR. Attenuation of NADPH oxidase activation and glomerular filtration barrier remodeling with statin treatment. Hypertension. 2008;51:474–480. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.102467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao T-D, Yang X-P, Liu Y-H, Shesely EG, Cavasin MA, Kuziel WA, Pagano PJ, Carretero OA. Role of Inflammation in the Development of Renal Damage and Dysfunction in Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;52:256–263. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.112706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen B, Hagiwara M, Yao YY, Chao L, Chao J. Salutary effect of kallistatin in salt-induced renal injury, inflammation, and fibrosis via antioxidative stress. Hypertension. 2008;51:1358–1365. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.108514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vera T, Kelsen S, Stec DE. Kidney-Specific Induction of Heme Oxygenase-1 Prevents Angiotensin II Hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;52:660–665. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Datla SR, Dusting GJ, Mori TA, Taylor CJ, Croft KD, Jiang F. Induction of Heme Oxygenase-1 In Vivo Suppresses NADPH Oxidase Derived Oxidative Stress. Hypertension. 2007;50:636–642. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagase M, Matsui H, Shibata S, Gotoda T, Fujita T. Salt-induced nephropathy in obese spontaneously hypertensive rats via paradoxical activation of the mineralocorticoid receptor: role of oxidative stress. Hypertension. 2007;50:877–883. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.091058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michea L, Villagran A, Urzua A, Kuntsmann S, Venegas P, Carrasco L, Gonzalez M, Marusic ET. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonism Attenuates Cardiac Hypertrophy and Prevents Oxidative Stress in Uremic Rats. Hypertension. 2008;52:295–300. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.109645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banday AA, Muhammad AB, Fazili FR, Lokhandwala M. Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress-Induced Increase in Salt Sensitivity and Development of Hypertension in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Hypertension. 2007;49:664–671. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000255233.56410.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briones AM, Rodriguez-Criado N, Hernanz R, Garcia-Redondo AB, Rodrigues-Diez RR, Alonso MJ, Egido J, Ruiz-Ortega M, Salaices M. Atorvastatin prevents angiotensin II-induced vascular remodeling and oxidative stress. Hypertension. 2009;54:142–149. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.133710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavi S, Yang EH, Prasad A, Mathew V, Barsness GW, Rihal CS, Lerman LO, Lerman A. The interaction between coronary endothelial dysfunction, local oxidative stress, and endogenous nitric oxide in humans. Hypertension. 2008;51:127–133. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gongora MC, Qin Z, Laude K, Kim HW, McCann L, Folz JR, Dikalov S, Fukai T, Harrison DG. Role of extracellular superoxide dismutase in hypertension. Hypertension. 2006;48:473–481. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000235682.47673.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin Z, Gongora MC, Ozumi K, Itoh S, Akram K, Ushio-Fukai M, Harrison DG, Fukai T. Role of Menkes ATPase in angiotensin II-induced hypertension: a key modulator for extracellular superoxide dismutase function. Hypertension. 2008;52:945–951. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chrissobolis S, Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Schrader LI, Dayal S, Lentz SR, Faraci FM. Glutathione peroxidase-1 plays a major role in protecting against angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2008;51:872–877. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Widder JD, Fraccarollo D, Galuppo P, Hansen JM, Jones DP, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Attenuation of angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction and hypertension by overexpression of Thioredoxin 2. Hypertension. 2009;54:338–344. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.127928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savoia C, Touyz RM, Amiri F, Schiffrin EL. Selective Mineralocorticoid Receptor Blocker Eplerenone Reduces Resistance Artery Stiffness in Hypertensive Patients. Hypertension. 2008;51:432–439. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei Y, Whaley-Connell AT, Habibi J, Rehmer J, Rehmer N, Patel K, Hayden M, DeMarco V, Ferrario CM, Ibdah JA, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonism Attenuates Vascular Apoptosis and Injury via Rescuing Protein Kinase B Activation. Hypertension. 2009;53:158–165. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.121954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagata D, Takahashi M, Sawai K, Tagami T, Usui T, Shimatsu A, Hirata Y, Naruse M. Molecular mechanism of the inhibitory effect of aldosterone on endothelial NO synthase activity. Hypertension. 2006;48:165–171. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000226054.53527.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sartorio CL, Fraccarollo D, Galuppo P, Leutke M, Ertl G, Stefanon I, Bauersachs J. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade improves vasomotor dysfunction and vascular oxidative stress early after myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2007;50:919–925. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doughan AK, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI. Molecular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction: linking mitochondrial oxidative damage and vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circ Res. 2008;102:488–496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graham D, Huynh NN, Hamilton CA, Beattie E, Smith RAJ, Cocheme HM, Murphy MP, Dominiczak AF. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant MitoQ10 Improves Endothelial Function and Attenuates Cardiac Hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2009;54:322–328. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guzik T, Hoch N, Brown K, McCann L, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison D. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204:2449. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crowley SD, Song Y-S, Sprung G, Griffiths R, Sparks M, Yan M, Burchette JL, Howell DN, Lin EE, Okeiyi B, Stegbauer J, Yang Y, Tharaux P-L, Ruiz P. A Role for Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptors on Bone Marrow-Derived Cells in the Pathogenesis of Angiotensin II-Dependent Hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:99–108. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takimoto E, Kass DA. Role of Oxidative Stress in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Remodeling. Hypertension. 2007;49:241–248. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000254415.31362.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ardanaz N, Yang X-P, Cifuentes ME, Haurani MJ, Jackson KW, Liao T-D, Carretero OA, Pagano PJ. Lack of Glutathione Peroxidase 1 Accelerates Cardiac-Specific Hypertrophy and Dysfunction in Angiotensin II Hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:116–123. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kobayashi A, Ishikawa K, Matsumoto H, Kimura S, Kamiyama Y, Maruyama Y. Synergetic Antioxidant and Vasodilatory Action of Carbon Monoxide in Angiotensin II Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2007;50:1040–1048. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hernandez Schulman I, Zhou M-S, Raij L. Cross-Talk Between Angiotensin II Receptor Types 1 and 2: Potential Role in Vascular Remodeling in Humans. Hypertension. 2007;49:270–271. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000253966.21795.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Touyz RM, Mercure C, He Y, Javeshghani D, Yao G, Callera GE, Yogi A, Lochard N, Reudelhuber TL. Angiotensin II-Dependent Chronic Hypertension and Cardiac Hypertrophy Are Unaffected by gp91phox-Containing NADPH Oxidase. Hypertension. 2005;45:530–537. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000158845.49943.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]