Abstract

We report the proteomes of four life cycle stages of the Apicomplexan parasite Eimeria tenella. A total of 1868 proteins were identified, with 630, 699, 845 and 1532 found in early oocysts (unsporulated), late oocysts (sporulated), sporozoites and second-generation merozoites, respectively. A MudPIT shotgun approach identified 812 sporozoite, 1528 merozoite and all of the oocyst proteins, whereas 2D gel proteomics identified 230 sporozoite and 98 merozoite proteins. Comparing the invasive stages, we find moving junction components RON2 in both, whilst AMA-1 and RON4 are found only in merozoites and AMA-2 and RON5 are only found in sporozoites, suggesting stage specific moving junction proteins. During early oocyst to sporozoite development, refractile body and most ‘glideosome’ proteins are found throughout, whilst microneme and most rhoptry proteins are only found after sporulation. Quantitative analysis indicates glycolysis and gluconeogenesis are the most abundant metabolic groups detected in all stages. The mannitol cycle ‘off shoot’ of glycolysis was not detected in merozoites but was well represented in the other stages. However, in merozoites we find more protein associated with oxidative phosphorylation, suggesting a metabolic shift mobilising greater energy production. We find a greater abundance of protein linked to transcription, protein synthesis and cell cycle in merozoites than in sporozoites, which may be residual protein from the preceding massive replication during schizogony.

Keywords: Coccidia, metabolism, invasion, Apicomplexa

1. Introduction

Eimeria species are parasitic protozoa belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa including species of great veterinary and medical significance such as Cryptosporidium, Neospora, Plasmodium, Theileria and Toxoplasma. Eimeria tenella is one of seven species that cause coccidiosis in chickens, a serious intestinal disease which results in economic losses of around $2.4 billion per annum worldwide [1]. Eimeria parasites have complex developmental life cycles with an exogenous phase in the environment during which oocysts excreted from the chicken undergo differentiation (sporulation) and become infective, and an endogenous phase in the intestine during which there are two or more (depending on the species) rounds of discrete, expansive asexual reproduction (schizogony) followed by sexual differentiation, fertilisation and shedding of unsporulated oocysts.

The unsporulated oocyst results from fertilisation of gametes and develops by the deposition of proteins (for example Gams 56, 82 and 230) from two distinct wall forming bodies into a multi-layered oocyst cell wall [2]. After shedding, unsporulated oocysts make contact with air and moisture and rapidly undergo meiosis (completed by ~ 9–12 hours of sporulation) and cell division to give rise to 8 haploid sporozoites (completed by ~24 hours of sporulation) [3]. When ingested by a chicken the sporozoites are liberated by mechanical abrasion of the oocyst wall in the chicken’s gizzard followed by enzymatic digestion of the sporocyst wall in the lumen of the upper intestine. Sporozoites migrate to their preferred sites of development (in the case of E. tenella, this is the caecum) where they invade villus enterocytes. Two species (Eimeria brunetti and Eimeria praecox) undergo their entire endogenous development within the villi but others, including E. tenella, develop within enterocytes of the crypts [4]; the mechanism by which sporozoites transfer from villi to crypts is not understood but may involve transportation within host intra-epithelial lymphocytes [5] or free migration of sporozoites between or across cells [6]. E. tenella undergoes two massive and distinct waves of schizogony in the crypts, which produce large numbers of first and second generation merozoites. A third round of schizogony, initiated by invasion of second generation merozoites and characterised by much smaller schizonts, is know to occur and may be obligatory [7], although it is possible that invasion of second generation merozoites may also initiate gametogony.

Sporozoites and merozoites of E. tenella share many features related to their invasive natures including proteins released from micronemes, which are important for host binding and invasion [8], rhoptry proteins secreted during invasion to form the parasitophorous vacuole within which the parasite resides [9], the use of actin based ‘glideosome’ to power host invasion [10] and the possession of GPI-linked variant surface antigens (SAGs), which may mediate binding to the host [11]. However sporozoites and merozoites also differ in some characteristics as follows: (1) The sporozoite stage is much longer-lived than any of the merozoite stages as it can remain dormant for many weeks within the oocyst until ingestion and excystation within the gut of a chicken. (2) After excystation, sporozoites migrate a considerable distance from the upper part of the small intestine along the gut lumen to invade enterocytes of the caecum [4] whereas merozoites invade locally and rapidly. (3) Sporozoites contain a unique pair of organelles termed the ‘refractile bodies’ that are hypothesised to be protein storage organelles [12] and which fragment and reduce in size in first-generation merozoites and are absent from second-generation merozoites. (4) Successive merozoite generations (but not sporozoites) are punctuated by intracellular schizont stages characterised by rapid and massive cell replication; producing up to 900, 350 and 16 daughter merozoites in the first, second and third generations respectively.

Eimeria genome sequencing is ongoing, thus previous global analysis of gene expression has largely been achieved by EST studies [13–15]. A previous proteomic analysis has identified a limited number of sporozoite proteins [16]. Here we describe the first large scale proteomic analysis of E. tenella unsporulated and sporulated oocysts, sporozoites and second-generation merozoites. We compare and contrast the distribution and abundance of proteins in the zoites and correlate these with possible shared or stage-specific invasive mechanisms. Furthermore proteins associated with organelles are followed from development of early oocyst to sporozoites.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Parasite production and purification

E. tenella (Houghton strain) oocysts were propagated, harvested from caeca and sporulated using standard protocols [17]. Early (unsporulated) oocysts were harvested after 9–12 hours, whilst as late oocysts were sporulated in vitro for 24–29 hours. Sporozoites were hatched from cleaned oocysts by in vitro excystation and purified over nylon wool and DE-52 cellulose columns [18]. Second-generation merozoites were recovered from the caecal mucosa of chickens 112 hours after inoculation with 5 × 105 sporulated oocysts [18].

2.2 2D- PAGE analysis (GEL LC-MS/MS)

Proteins from 108 purified sporozoites were resolved by 2D-PAGE and identified by mass spectrometry as previously described [19]. Briefly, proteins were solubilised in urea and resolved on either pH3-10 or pH4-7 gels. Protein spots were stained with colloidal Coomassie, excised, digested with trypsin and subjected to MS/MS analysis as described [19].

Proteins from 108 purified merozoites were solubilised in 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (w/v) CHAPS, 2% (v/v) IPG Buffer, 40 mM DTT and resolved on either pH 3–10 or pH 4–7 2D gels. Protein spots were silver stained and destained with 15mM potassium ferricyanide/50mM sodium thiosulphate for 5 min, reduced with 10mM DTT/100mM ammonium bicarbonate for 30 min and alkylated with 55mM iodoacetamide/100mM ammonium bicarbonate for 20 min. Spots were washed with 100mM ammonium bicarbonate and dehydrated with 100% (v/v) acetonitrile. Proteins were digested with 6ng/μl trypsin/50mM ammonium bicarbonate for 5 hours at 37°C and peptides were extracted in 1% (v/v) formic acid/2% (v/v) acetonitrile and secondly in 50% (v/v) acetonitrile. Tryptic peptides (5 μl) were desalted and concentrated on a C18 TRAP (180μm × 20mm, 5μm Symmetry, Waters), for 3 min at 10 μl/min, and resolved on a 1.7μm BEH 130 C18 column (100μm × 100mm, Waters) at 400 nl/min attached to Waters UPLC Acquity HPLC. Peptides were eluted at 400 nl/min with a linear gradient of 0–50% (v/v) acetonitrile/0.1% (v/v) formic acid over 30 min, followed by 85% (v/v) acetonitrile/0.1% (v/v) formic acid for 7 min. Ionised peptides were analysed by a Waters Quadrupole Time of Flight Premier Mass Spectrometer in data directed acquisition mode, tuned using 200 fmol/μl human glutamate fibrinopeptide B in (v/v) 0.1% formic acid/(v/v) 50% acetonitrile/water. Peaklists were created from raw spectral data with ProteinLynx Global server version 2.2.5 (Waters), using the following criteria: external calibration with lockmass of 785.8426 (M+H2+) of glutamate fibrinopeptide B, adaptive type background subtraction combining all scans and deisotoping with a threshold of 5%.

The resulting peak lists from both sporozoites and merozoites were submitted to MASCOT version 2.0 (Matrix Science, UK) and searched against a locally installed protein database composed of: E. tenella predicted proteins (Workflow-based Automatic Genome Annotation or WAGAs). Also included were predicted proteins from possible contaminants Gallus gallus (NCBI, 112806 Assembly) and Homo sapiens (NCBI, 030408 Assembly). Database search settings selected trypsin as the enzyme, allowed one missed cleavage, carbamidomethylated cysteine as fixed modification, oxidised methionine as potential variable modification, peptide tolerance of ± 200 ppm, MS/MS tolerance of ± 0.2 Da and +2 and +3 peptide charge states. The WAGA E. tenella predicted proteins were derived from the 020407 Genome Assembly (The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute) and gene models were predicted using gene prediction programs GlimmerHMM, SNAP, PHAT, TwinScan, GeneFinder and Apicomplexa gene models which were refined using 70,000 ESTs, 8775 peptides detected by MudPIT or gel LC-MS/MS, (Xikun Wu (IAH) and The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, unpublished data). Sporozoite proteins were analysed from a total of four gels (pH 3–10A, pH 3–10B, pH 4-7A and pH4-7B) and merozoite proteins were identified from two gels (pH 3–10 and pH 4–7).

2.3 Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT)

Sporozoite, merozoite, early and late oocyst proteins were each analysed by MudPIT as previously described [19]. Briefly, proteins were solubilised in 2M urea 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5 and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 30 min at 4°C to separate soluble from insoluble fractions. Both fractions were digested with endoproteinase Lys-C and trypsin [19]. Peptide mixtures were analyzed by MudPIT [20]. A quaternary Agilent 1100 series HPLC coupled directly to a Finnigan LTQ-ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo, San Jose, CA) equipped with a nano-LC electrospray ionization source [21] resolved peptide mixtures by strong cation exchange liquid chromatography upstream of reverse-phase liquid chromatography [22]. Fully-automated 12 step chromatography was carried out on each sample. Good quality spectra were filtered as previously described [23] and compared, using SEQUEST (version 27), to a database of predicted proteins from E. tenella (WAGA), chicken, human and a reverse sequence database was included to estimate the false positive rate. No enzyme specificity was considered for any search. All searches were parallelized and performed on a Beowulf computer cluster consisting of 100 1.2 GHz Athlon CPUs. Results were assembled and filtered using DTASelect (version 2.0) to estimate the false positive rate (<6%). Triplicate samples of each life cycle stage were analysed and combined to create a non-redundant catalogue.

The abundance of a protein detected by MudPIT is reflected in the number of peptides detected [24], spectrum count [25] and sum of cross correlation scores (Xcorr) [26]. The Xcorr score quantitates the relatedness of experimental tandem mass spectra to in silico generated tandem mass spectra from sequence databases. This calculation includes the number of fragment ions in the mass spectrum, their relative abundance, continuity of ion series and presence of immonium ions for certain amino acids in the spectrum; all of which are proportional to the concentration of the precursor ion. To assess the abundance of protein associated with a functional category we summed the a) peptide number, b) spectrum count or c) sum of Xcorr of each protein detected associated with the functional category. We normalised for the total a) peptides, b) spectrum or c) sum of Xcorr of all proteins detected in each stage and observed trends consistent in the three different measures of protein abundance.

2.4 ‘In silico’ analysis of identified proteins

Predicted Eimeria protein sequences with matching peptides (WAGAs_detected.fasta attached) were identified. Identifications were attributed by combining data from several sources in order of importance; 1) similarity to E. tenella published sequences deposited in NCBI (BLAST searches), 2) predicted domains (InterProScan [27]), 3) Plasmodium falciparum, Theileria anulata and Toxoplasma gondii orthologues (identified by Inparanoid [28]), 4) a significant BLAST score to Swiss-Prot or 5) NCBI redundant databases. In addition, characterised SAG family sequences were provided by Chandra Subramaniam and Fiona Tomley (unpublished data). E. tenella orthologues of described Apicomplexan rhoptry protein sequences were found by Inparanoid and BLAST. All identified proteins were assigned one functional classification using the MIPS Functional Catalogue Database (FunCatDB) [29] as modified for Plasmodium [30]. E. tenella proteins with orthologues in P. falciparum or S. cerevisiae with ascribed MIPS [29, 30] were assigned the same category. Proteins lacking orthologous MIPS annotation were manually assigned a category. Proteins with metabolic functions were further classified into pathways using a) InterPro domain to Gene Ontology mapping (http://www.geneontology.org/external2go/interpro2go), b) KAAS (KEGG Automatic Annotation Server at http://www.genome.jp/kegg/kaas/), which uses BLAST comparisons to the KEGG pathway database and c) additional manual curation.

Proteins associated with the secretory pathway were identified by the presence of either a signal peptide or transmembrane domain(s), assessed by Phobius [31]. Secretory proteins putatively imported to the apicoplast were identified with PATS [32], or modified by the addition of a GPI anchor were predicted by the big-PI predictor [33] or PredGPI (http://gpcr.biocomp.unibo.it/predgpi/pred.htm). Cytoplasmic proteins putatively imported to the nucleus or mitochondria were identified with NucPred [34] and PlasMit [35], respectively.

3. Results

3.1 Proteomic identification of proteins by MudPIT and GEL LC-MS/MS

A total of 1868 non-redundant proteins was detected from all of the stages that were analysed (Table S1).

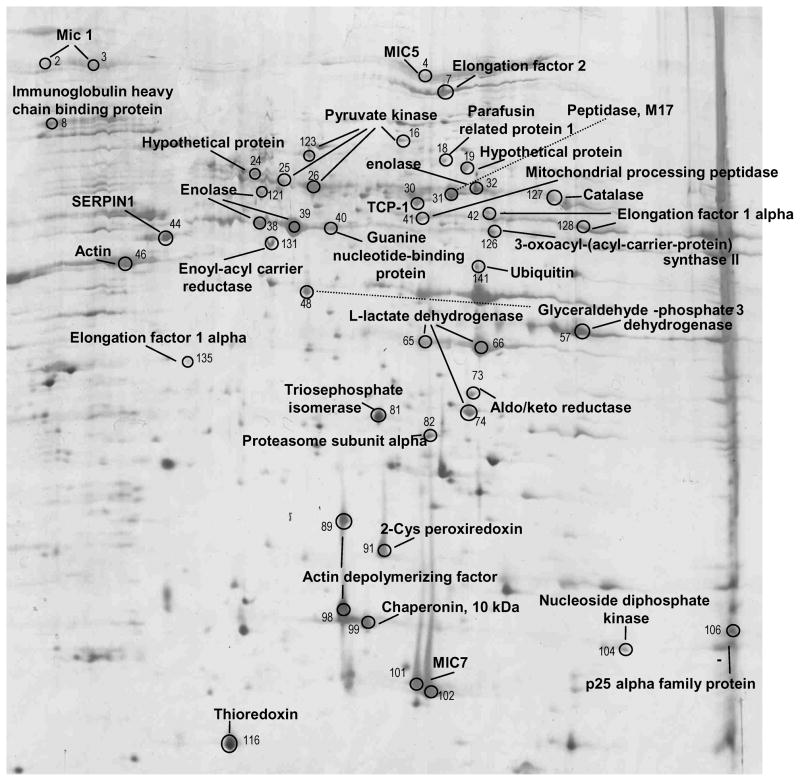

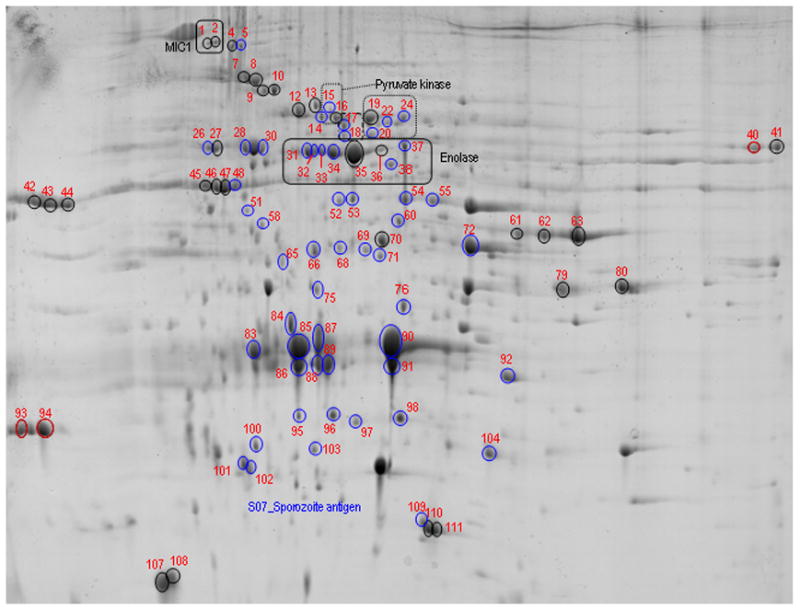

Merozoite lysates analysed by MudPIT or LC-MS/MS identified a non-redundant dataset of 1532 proteins. MudPIT detected 1528 of these proteins with a minimum of two peptides (Table S2) and LC-MS/MS, using a combination of broad (pH 3–10) and narrow (pH 4–7) range 2-DE gels (Figs. 1 and S1), resulted in 136 protein spots (Table S3) from which 1810 peptides were identified within a non-redundant dataset of 98 proteins. The majority of proteins identified by gel LC-MS/MS (91 proteins) were also identified by MudPIT (Table S1), generally by a significant number of peptides, suggesting that these are abundant molecules.

Figure 1. pH 3–10 NL proteome map of E. tenella merozoites.

Soluble proteins from 108 merozoites were resolved by IEF over a broad, nonlinear pH 3–10 range followed by molecular mass on a 12.5% w/v acrylamide gel under denaturing conditions. Protein spots are visualised using silver stain. All protein identifications are labelled on the gel, the spots are numbered and the list of protein identifications is given in Table S3.

Sporozoite lysates analysed by either MudPIT or LC-MS/MS identified a total of 845 non-redundant proteins. MudPIT analysis of sporozoite lysates identified 812 proteins, with two or more peptide matches (Table S4). Sporozoite proteins were also resolved on four 2-DE gels; pH 3-10A, pH 3-10B, pH 4-7A, pH 4-7B (Figs 2, S2-S4). Electrospray mass spectrometry identified 13,254 peptides from 371 spots, identifying 230 individual proteins (Tables S5-S8), including an additional 36 proteins not found by MudPIT.

Figure 2. Gel pH 3–10 NL (A) resolving E. tenella sporozoite proteins highlighting proteins identified from multiple spots.

Soluble proteins from 108 sporozoites were resolved by IEF over a broad, nonlinear pH 3–10 range followed by molecular mass on a 12.5% w/v acrylamide gel under denaturing conditions. Protein spots are visualised using Coomassie Colloidal stain. Representative proteins identified in multiple spots are labelled on the gel, SO7 antigen was identified in all spots ringed blue. The spots are numbered and the complete list of protein identifications are given in Table S5.

MudPIT detected 630 and 699 non-redundant proteins from early and late oocysts respectively (minimum two peptides) (Tables S9 & S10); these stages were not analysed by LC-MS/MS.

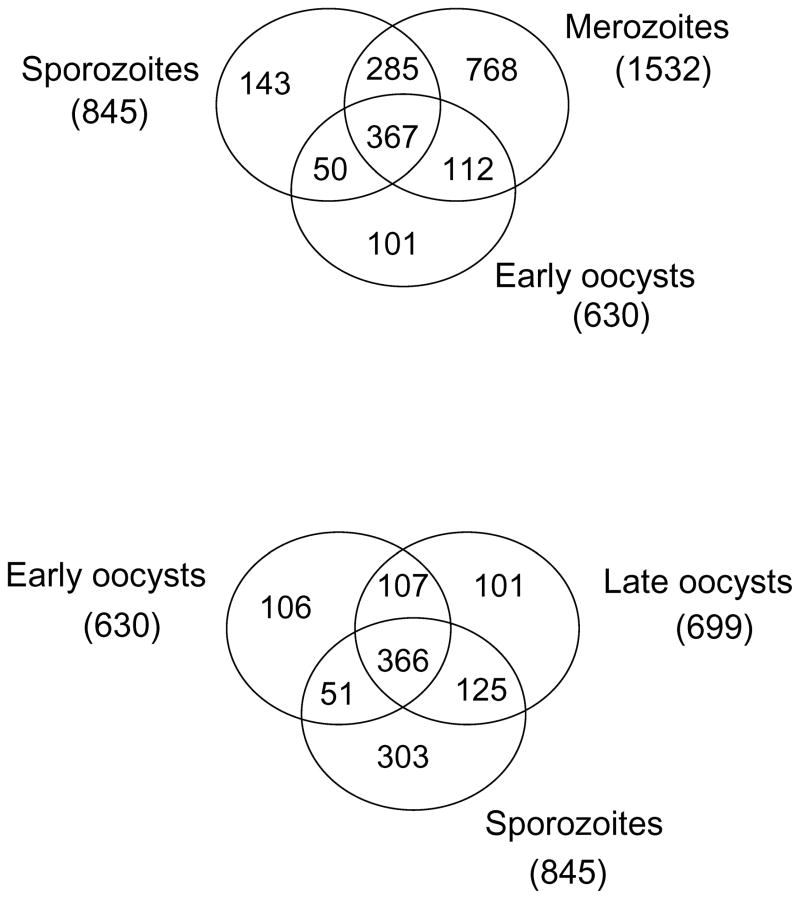

The E. tenella WAGA database contains a total of 6659 predicted proteins. Thus, we detect ~23%, 13%, 9% and 10% of all predicted proteins in the merozoite, sporozoite, early and late oocysts, respectively. The percentage of chicken proteins identified within each Eimeria life cycle preparation ranged between, 7.3% with sporozoites and 3.6% with early oocyst, indicating low contamination with host proteins. Figure 3 illustrates the degree of overlap between the datasets derived from each life cycle stage.

Figure 3. Protein numbers detected in the merozoite, sporozoite, early and late oocyst proteomes.

Venn diagram to show the numbers of proteins identified in merozoite, sporozoite, and early and late oocyst stages by either MudPIT or 2D LC-MS/MS. Proteins shared by the different life cycle stages are shown.

3.2 Proteins are found in multiple spots on 2D gels

Analysis of proteins by 2D gel and LC-MS/MS revealed that individual proteins are often found in multiple spots. Sporozoite proteins analysed from gels pH3-10A, pH3-10B, and pH4-7A show 81/144, 47/102 and 27/92 proteins respectively are found in more than one spot (Tables S5-S8). Merozoite proteins analysed from pH4-7A and pH3-10 show 28/76 and 10/38 proteins are also found in more than one spot (Table S3). Several proteins, if detected, are consistently found in multiple spots and a selection of these is shown in Table S11.

3.3 Detection of previously characterised proteins

We detected 47 SAG surface proteins in the merozoite whilst only four were found in the sporozoite. Microneme proteins MIC1-5 & MIC7-9 [36–39] were detected in both merozoites and sporozoites and the majority of microneme proteins (MIC1-5 & MIC7) were also identified in the fully sporulated oocyst but all were absent from the early oocyst. Microneme proteins AMA-1 was detected only in sporozoites and AMA-2 was only detected in merozoites. Rhoptry neck proteins RON2, RON3 and RON4 were found in the merozoite, whilst RON2 and RON5 were found in both the sporozoite and late oocyst. The rhoptry proteases, Tg subtilisin 2 orthologue was found in the merozoite and Tg toxopain orthologue was identified in all stages analysed. No rhoptry proteins were found in the early oocyst apart from toxopain. In contrast the oocyst wall proteins Gam56 and Gam 82 [2] were readily detected in both early and late oocysts but were not found in either of the zoite stages.

‘Glideosome’ proteins actin, myosin A, myosin A tail interacting protein (MTIP), aldolase, profilin, actin depolymerizing factor (ADF) were detected in both of the motile stages, the merozoite and sporozoite. All described ‘glideosome’ proteins, with the exception of myosin A and MTIP were also detected in the early oocyst.

Proteins previously described as residing in the refractile bodies or at the sporozoite apex, such as Eimepsin [40], S07 antigen [41], and pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase [42] were found in the sporozoite, early and late oocyst proteomes but were absent or expressed at low levels in the second-generation merozoites. Putative refractile body proteins lactate dehydrogenase, carbonyl reductase and haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase [12] were found in all stages analysed.

Cell cycle related proteins cyclin-dependent kinase [43] and MORN-domain containing proteins [44] (of which we detect three) were only detected in the merozoite stage.

The mannitol cycle is an ‘off shoot’ of the glycolytic pathway and component proteins; mannitol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase, mannitol-1-phosphatase and mannitol dehydrogenase are detected in the unsporulated, sporulated oocysts and sporozoites but were not found in merozoites.

3.4 Functional analysis and predicted localisations of proteins detected in each life cycle stage

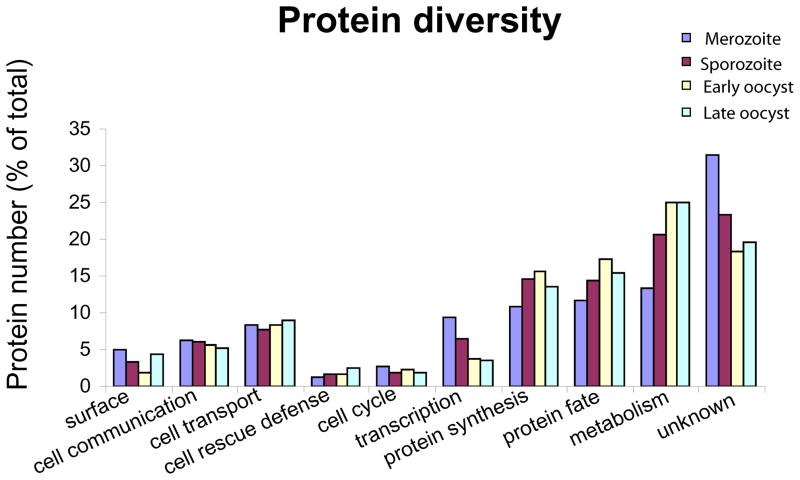

To investigate the functional composition of the proteomes described, we classified each protein detected into a MIPS functional category (Table S1). We reasoned that if a developmental stage performs a greater range of roles associated with a functional category, it might be expected to use a greater diversity of proteins. The range of proteins associated with each functional category is represented by the number of different proteins detected in the functional category normalised for total number of different proteins detected, for each life cycle stage (Fig. 4). The majority of proteins detected are of unknown function or are involved in metabolism. A considerable number of proteins are categorised as protein synthesis and protein fate, whilst those associated with the cell cycle are few in number. There appears to be no major differences between the life cycle stages in the range of proteins associated with the functional groups.

Figure 4. Numbers of proteins identified from the functional categories in the merozoite, sporozoite, early and late oocyst proteomes.

Homology to better characterised proteins allowed MIPs functional categorisation of the proteins detected by either MudPIT or 2D gel LC-MS/MS (Table S1). Protein diversity is represented as the number of proteins found in each category, expressed as a percentage of the total detected in each stage.

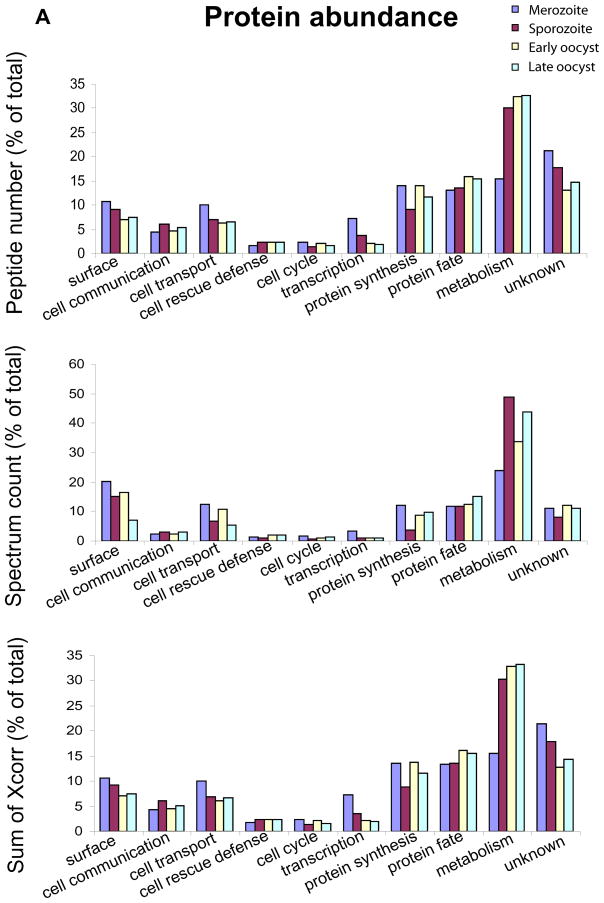

We reasoned that even if two parasite life cycle stages perform a similar range of functions (reflected in associated protein diversity), one stage may be performing a function to a greater degree and this may be reflected in the protein abundance associated with the functional categories. Thus, we estimated the relative amount of protein associated with each functional category in each life cycle stage as assessed by a) the sum of peptide number, b) the sum of spectrum count or c) sum of Xcorr (Fig. 5A, B and C). We find metabolism to be the largest category of protein abundance in all stages analysed, except the merozoite. Identification of a larger number of merozoite proteins has possibly allowed identification of a greater number of lower abundance proteins of unknown function. Compared to the sporozoite we detect in the merozoite, two-fold more protein associated with transcription, 1.5 fold more involved in protein synthesis and 1.7 fold more linked with cell cycle functions. Also compared to the sporozoite, we detect over 1.5 fold more protein associated with protein synthesis and cell cycle functions in the early oocyst.

Figure 5. Protein abundances associated with the functional categories in the merozoite, sporozoite, early and late oocyst proteomes.

The abundance of proteins detected by MudPIT associated with each functional category is represented by A) the total number of peptides detected B) the total spectrum count and C) the sum of the Xcorr scores. Each category is expressed as a percentage of the total detected in each stage.

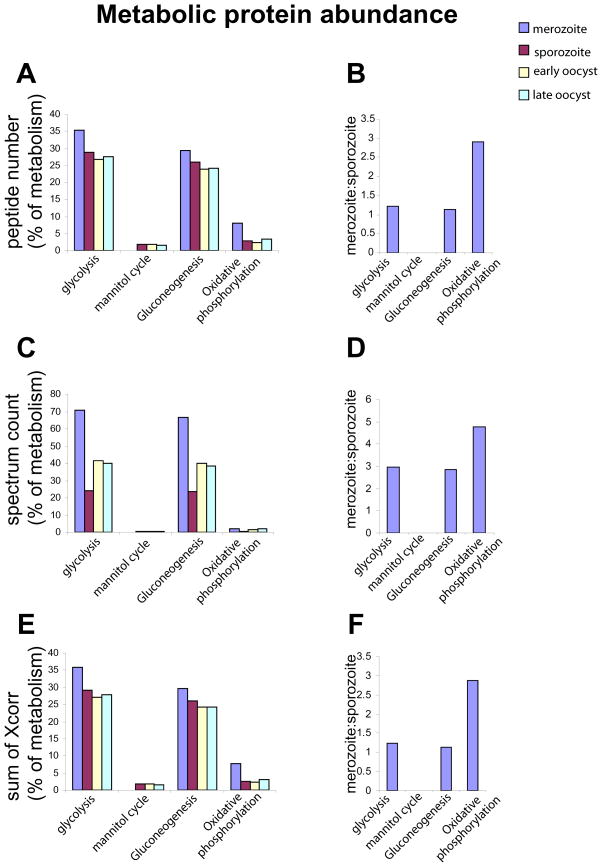

We analysed proteins associated with metabolism in more detail, categorising them further into the main metabolic pathways (Table S1). As mentioned in results 3.3 proteins associated with the mannitol cycle were found in all stages apart from merozoites. The range of proteins associated with the remaining main metabolic pathways appears similar in all the life cycle stages (Fig. S5). Analysis of the protein abundances’ found, indicates that the most abundant group of metabolic proteins are involved in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis in all life cycle stages (Fig. 6A, C & E). Despite the apparently small contribution of protein to oxidative phosphorylation, it is three times more abundant in merozoites than the sporozoite or the oocyst stages (Fig. 6B, D & F), despite using a similar repertoire of proteins (Fig. S5). Proteins associated with nucleotide metabolism were more abundant in merozoites than the other stages (2 fold more than sporozoites) (Table S12). In comparison, proteins of other metabolic pathways are equally abundant (Table S12).

Figure 6. Protein abundances involved in metabolic pathways in merozoites, sporozoites, early and late oocysts.

Metabolism associated proteins detected by MudPIT were further categorised into metabolic pathways and the relative protein investment in each pathway by each life cycle stage is shown. The total numbers of peptides (A & B), spectrum (C & D) and sum of Xcorr scores (E & F), are represented as a proportion of the total involved in metabolism in each life cycle stage in A, C and E, or as the ratio of merozoite:sporozoite protein proportions (B, D and F).

Approximately 25% of sporozoite proteins are identified as being part of the secretory pathway compared to 30% of merozoite proteins (Fig. S6). The merozoite is predicted to add a GPI anchor to 68 proteins compared to only 16 sporozoite proteins detected (mostly SAG proteins). As expected the majority of proteins in all stages are cytoplasmic, ranging between 59%-66% in merozoites and sporozoites, respectively. Only 13 proteins are predicted to target to the Apicoplast using the prediction program PATS (Table S1).

4. Discussion

Our description of the sporozoite proteome extends the previous description of 28 sporozoite proteins [16] and adds the first proteomes of second-generation merozoites and both unsporulated and sporulated oocysts. We detect 28% of all E. tenella predicted proteins in all stages analysed, with 23% of predicted proteins found in the merozoite. The published proteomes of P. falciparum merozoites [30] and Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites [45] describe detection of 15% and 29% of their respective predicted proteins. Thus comparatively our detection coverage of merozoite proteins is good. We find 13%, 9% and 10% of predicted proteins from sporozoites, early and late oocysts respectively, suggesting that the protein detection coverages although respectable, are unlikely to be exhaustive.

The 288 proteins found in both sporozoites and merozoites but not in the early oocysts (Fig. 3A) may have functions associated with invasive mechanisms shared by the zoites. Proteins found in both zoites include microneme proteins involved in host adhesion and ‘glideosome’ proteins which drive motility, an essential component process of invasion. During parasite invasion of the host cell an intimate contact, the moving junction, is formed and includes proteins secreted from the micronemes (AMA-1) or rhoptry neck (RON2, RON4 and RON5) in T. gondii [46, 47]. These proteins are thought to play a conserved function in P. falciparum [48] and are therefore likely to act similarly in E. tenella. Indeed RON2 and RON5 has been identified in enriched E. tenella sporozoite rhoptry fractions (Tomley unpublished data). Our detection of an isoform of AMA-1 and RON2 in both zoites suggests a similar moving junction is common to invasion of both. However, we find AMA-1 and RON4 in merozoites only and AMA-2 and RON5 in sporozoites only. The stage specific expression of AMA-1 and AMA-2 has been confirmed by transcription analysis (Tomley unpublished data). This suggests that moving junction proteins differ between merozoites and sporozoites. Both RON4 and RON5 locate to the cytoplasmic face of the host cell membrane of the moving junction [49], but as both zoites invade chicken gut enterocytes, it remains unclear why distinct proteins would be present in the moving junctions of the two invasive stages.

Additional, protein differences between the zoites include the large range of SAG surface proteins found in the merozoite whilst few are detected in the sporozoite. SAG proteins are hypothesised to assist with host cell binding and greater merozoite SAG diversity may increase the avidity of binding to the host receptors aiding rapid invasion of this short lived zoite.

Proteins shared across the development of early/late oocysts and then to sporozoites (Fig. 3B) highlight differences in protein development associated with specific organelles. Refractile body proteins, the majority of ‘glideosome’ proteins and the rhoptry protease toxopain are found in the early oocyst in addition to the sporulated oocyst and sporozoite. Indeed, SO7 antigen, ADF and profilin proteins have been previously reported in all four stages [40, 50, 51]. As the early oocyst has neither refractile bodies, nor a pellicle [52] to support ‘glideosome’ activity, nor rhoptries with proteins which require proteolytic processing, these proteins are likely to be found at alternative locations and may perform additional roles in the early oocyst. In contrast microneme proteins and the majority of rhoptry proteins are only found in the later two stages of oocyst to sporozoite development. Micronemes and rhoptries are first visible by electron microscopy after sporozoite formation in the late oocyst [52]. Indeed, detailed analysis of MICs 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 proteins showed they are initially found 22.5 hours after initiation of sporulation, concurrent with the formation of recognisable sporozoites [3]. This suggests microneme and most rhoptry proteins are not pre-synthesised but synthesis coincides with development of the apical complex during sporozoite formation.

Most metabolic proteins detected appear to be associated with gluconeogenesis or glycolysis in all life cycle stages (Fig. 6A, C, E). If protein abundance reflects the contribution to energy production, gluconeogenesis and glycolysis are likely to be the major contributors, similar to Toxoplasma tachyzoites [53]. The mannitol cycle appears well represented in oocyst stages and sporozoites but we do not identify these proteins in the merozoite. This is consistent with previous reports of substantial up-regulation of the mannitol cycle during sexual development [54]. Importantly, the drug Megasul inhibits mannitol-1-phosphate, blocking oocyst development and transmission of the parasite to subsequent hosts [55]. On the other hand, we detect more protein linked to oxidative phosphorylation in merozoites compared to the other life cycle stages. Every stage has proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. S5) and electron microscopy shows the mitochondria of all stages contain similar internal membrane structures to support oxidative phosphorylation. However, the dramatic difference in protein abundance observed suggests a metabolic shift to use oxygen to mobilise greater energy production in the merozoite. Indeed, sporozoite excystation is adapted to low oxygen conditions [56]. It has also been suggested that the parasite uses anaerobic glycolysis during schizogony but switches to aerobic metabolism immediately before merozoite release [57]. The glycolytic proteins pyruvate kinase and enolase relocate from the cytoplasm/nucleus to the parasite apex in both merozoites and sporozoites in contact with host cells [58]. Moreover both proteins are secreted under conditions identical to microneme release i.e. incubation with FCS at 41°C and secretion is inhibited by the kinase inhibitor staurosporine [58]. These data suggest a role for these proteins at the time of invasion. Furthermore, in Toxoplasma tachyzoites five metabolic proteins involved in glycolysis or lactic acid fermentation relocate during parasite invasion from the cytoplasm to the pellicle [53]. Thus, proteins involved in ATP production including those with oxidative phosphorylation roles may produce energy necessary for invasion and the merozoite may have a greater invasive energy requirement.

Transcription, protein synthesis and nucleotide metabolism all show greater protein abundances detected in the merozoite than the sporozoite (Fig. 5 and Table S12). Greater commitment to protein synthesis in the merozoite compared to the sporozoite is consistent with previous reports of large scale EST analysis. Analysis of 13,450 merozoite and 13,255 sporozoite ESTs revealed 9.5% of merozoite but only 0.2% of sporozoite ESTs were ribosomal proteins [59]. Whilst the amount of protein involved in the cell cycle is small, we detect more in merozoites than sporozoites. Consistent with the greater abundance of cell cycle proteins, we detect MORN-domain proteins only in the merozoite. It is possible that these increased protein abundances are residual protein related to the massive replication (~350 fold) recently undergone during schizogony. Consistent with replication during sporulation (8 fold), we detect a greater abundance of protein linked to cell cycle and protein synthesis in early oocysts than sporozoites (over 1.5 fold more for both categories).

The PATS algorithm predicts few proteins to target to the apicoplast in Eimeria. PATS uses P. falciparum sequences to model apicoplast targeting and the programs authors suggest ‘it may not work’ with the related Apicomplexan T. gondii (http://gecco.org.chemie.uni-frankfurt.de/pats/pats-index.php). Indeed PATS fails to predict the described E. tenella apicoplast protein enoyl reductase [60]. This suggests that the apicoplast targeting sequence in Plasmodium differs from Eimeria and PATS under-predicts Eimeria apicoplast targeted proteins.

Many proteins identified by 2D gel LC-MS/MS were found in multiple protein spots. For highly abundant proteins such as SO7, incomplete protein solubilisation and resolution on the 2D gel can lead to detection in multiple spots, however, in many cases differential protein resolution is likely to be the result of proteolytic processing and post-translational modifications. For example enolase is post translationally modified by either glycosylation or phosphorylation which regulates it’s location and function in vivo [61, 62]. Also, MIC1 belongs to the Thrombospondin-Related Anonymous Protein-like protein family [63] which undergo cleavage at sequential protein developmental points which are critical to invasion [64].

E. tenella gene architecture has proved extremely complex, exhibiting a large number of introns which are frequently alternatively spliced. Previous gene models were based on gene prediction programs which often disagreed. Our peptide data, together with EST data, was used to select detected gene models, such that the previous redundant database of 41,430 putative predicted proteins was condensed to the non-redundant WAGA database of 6,659 proteins (Wu and Tomley et al manuscript in preparation). Thus, this proteomic analysis has provided 8775 detected peptides with which to re-annotate Eimeria tenella gene models. In addition, we provide the first evidence that the 579 ‘hypothetical proteins’ detected are indeed expressed proteins and combined with evidence of expression patterns in the different life cycles stages, this work may inform the development of new intervention targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We extend our generous thanks to Derek Huntley for bioinformatic support and to Dominic Kurian and Lawrence Hunt for technical help with proteomic analysis of the merozoite samples. This work was supported by BBSRC Grant BBS/B/03858. John R Yates III is supported by NIH P41 RR011823 and Judith Helena Prieto is supported by NIH-NIAID grant number R21 AI072615-01.

Abbreviations

- WAGA

Workflow-based Automatic Genome Annotation

- MudPIT

Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology

- KAAS

KEGG Automatic Annotation Server

- MTIP

myosin A tail interacting protein

- Xcorr

cross correlation scores

- ADF

actin depolymerizing factor

- FunCatDB

The MIPS Functional Catalogue Database

References

- 1.Shirley MW, Smith AL, Tomley FM. The biology of avian Eimeria with an emphasis on their control by vaccination. Adv Parasitol. 2005;60:285–330. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)60005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson DJ, Belli SI, Smith NC, Wallach MG. The development of the macrogamete and oocyst wall in Eimeria maxima: immuno-light and electron microscopy. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan R, Shirley M, Tomley F. Mapping and expression of microneme genes in Eimeria tenella. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:1493–1499. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose ME, Lawn AM, Millard BJ. The effect of immunity on the early events in the life-cycle of Eimeria tenella in the caecal mucosa of the chicken. Parasitology. 1984;88:199–210. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000054470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawn AM, Rose ME. Mucosal transport of Eimeria tenella in the cecum of the chicken. J Parasitol. 1982;68:1117–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vervelde L, Jeurissen SH. The role of intra-epithelial and lamina propria leucocytes during infection with Eimeria tenella. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;371B:953–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald V, Rose ME. Eimeria tenella and E. necatrix: a third generation of schizogony is an obligatory part of the developmental cycle. J Parasitol. 1987;73:617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Periz J, Gill AC, Hunt L, Brown P, Tomley FM. The microneme proteins EtMIC4 and EtMIC5 of Eimeria tenella form a novel, ultra-high molecular mass protein complex that binds target host cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16891–16898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greif G, Entzeroth R. Eimeria tenella: localisation of rhoptry antigens during parasite-host cell interactions by a rhoptry-specific monoclonal antibody in PCKC culture. Appl Parasitol. 1996;37:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bumstead J, Tomley F. Induction of secretion and surface capping of microneme proteins in Eimeria tenella. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;110:311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tabares E, Ferguson D, Clark J, Soon PE, et al. Eimeria tenella sporozoites and merozoites differentially express glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored variant surface proteins. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;135:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Venevelles P, Chich JF, Faigle W, Lombard B, et al. Study of proteins associated with the Eimeria tenella refractile body by a proteomic approach. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1399–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klotz C, Marhofer RJ, Selzer PM, Lucius R, Pogonka T. Eimeria tenella: identification of secretory and surface proteins from expressed sequence tags. Exp Parasitol. 2005;111:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miska KB, Fetterer RH, Barfield RC. Analysis of transcripts expressed by Eimeria tenella oocysts using subtractive hybridization methods. J Parasitol. 2004;90:1245–1252. doi: 10.1645/GE-309R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Brunk BP, Kissinger JC, Pape D, et al. Gene discovery in the apicomplexa as revealed by EST sequencing and assembly of a comparative gene database. Genome Res. 2003;13:443–454. doi: 10.1101/gr.693203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Venevelles P, Chich JF, Faigle W, Loew D, et al. Towards a reference map of Eimeria tenella sporozoite proteins by two-dimensional electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1321–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long PL, Millard BJ, Joyner LP, Norton CC. A guide to laboratory techniques used in the study and diagnosis of avian coccidiosis. Folia Vet Lat. 1976;6:201–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirley M. In: Biotechnology- guidlines on techniques in coccidiosis research. Eckert JBR, Shirley MW, Coudert P, editors. Luxembourg: European Commission DGXII; 1995. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanderson SJ, Xia D, Prieto H, Yates J, et al. Determining the protein repertoire of Cryptosporidium parvum sporozoites. Proteomics. 2008;8:1398–1414. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Link AJ, Eng J, Schieltz DM, Carmack E, et al. Direct analysis of protein complexes using mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:676–682. doi: 10.1038/10890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatlin CL, Kleemann GR, Hays LG, Link AJ, Yates JR., 3rd Protein identification at the low femtomole level from silver-stained gels using a new fritless electrospray interface for liquid chromatography-microspray and nanospray mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1998;263:93–101. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bern M, Goldberg D, McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd Automatic quality assessment of peptide tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2004;20 (Suppl 1):i49–54. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao J, Opiteck GJ, Friedrichs MS, Dongre AR, Hefta SA. Changes in the protein expression of yeast as a function of carbon source. J Proteome Res. 2003;2:643–649. doi: 10.1021/pr034038x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Sadygov RG, Yates JR., 3rd A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4193–4201. doi: 10.1021/ac0498563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanduri B, Lawrence ML, Vanguri S, Burgess SC. Proteomic analysis using an unfinished bacterial genome: the effects of subminimum inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on Mannheimia haemolytica virulence factor expression. Proteomics. 2005;5:4852–4863. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W116–120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remm M, Storm CE, Sonnhammer EL. Automatic clustering of orthologs and in-paralogs from pairwise species comparisons. J Mol Biol. 2001;314:1041–1052. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.5197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruepp A, Zollner A, Maier D, Albermann K, et al. The FunCat, a functional annotation scheme for systematic classification of proteins from whole genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5539–5545. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Florens L, Washburn MP, Raine JD, Anthony RM, et al. A proteomic view of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. Nature. 2002;419:520–526. doi: 10.1038/nature01107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction--the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W429–432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuegge J, Ralph S, Schmuker M, McFadden GI, Schneider G. Deciphering apicoplast targeting signals-feature extraction from nuclear-encoded precursors of Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast proteins. Gene. 2001;280:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenhaber B, Bork P, Eisenhaber F. Post-translational GPI lipid anchor modification of proteins in kingdoms of life: analysis of protein sequence data from complete genomes. Protein Eng. 2001;14:17–25. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brameier M, Krings A, MacCallum RM. NucPred--predicting nuclear localization of proteins. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1159–1160. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bender A, van Dooren GG, Ralph SA, McFadden GI, Schneider G. Properties and prediction of mitochondrial transit peptides from Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;132:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labbe M, de Venevelles P, Girard-Misguich F, Bourdieu C, et al. Eimeria tenella microneme protein EtMIC3: identification, localisation and role in host cell infection. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;140:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomley FM, Billington KJ, Bumstead JM, Clark JD, Monaghan P. EtMIC4: a microneme protein from Eimeria tenella that contains tandem arrays of epidermal growth factor-like repeats and thrombospondin type-I repeats. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomley FM, Bumstead JM, Billington KJ, Dunn PP. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel acidic microneme protein (Etmic-2) from the apicomplexan protozoan parasite, Eimeria tenella. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;79:195–206. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawazoe U, Tomley FM, Frazier JA. Fractionation and antigenic characterization of organelles of Eimeria tenella sporozoites. Parasitology. 1992;1:1–9. doi: 10.1017/s003118200006073x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jean L, Grosclaude J, Labbe M, Tomley F, Pery P. Differential localisation of an Eimeria tenella aspartyl proteinase during the infection process. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:1099–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fetterer RH, Jenkins MC, Miska KB, Barfield RC. Characterization of the antigen SO7 during development of Eimeria tenella. J Parasitol. 2007;93:1107–1113. doi: 10.1645/GE-1171R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vermeulen AN, Kok JJ, van den Boogaart P, Dijkema R, Claessens JA. Eimeria refractile body proteins contain two potentially functional characteristics: transhydrogenase and carbohydrate transport. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;110:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinnaird JH, Bumstead JM, Mann DJ, Ryan R, et al. EtCRK2, a cyclin-dependent kinase gene expressed during the sexual and asexual phases of the Eimeria tenella life cycle. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferguson DJ, Sahoo N, Pinches RA, Bumstead JM, et al. MORN1 has a conserved role in asexual and sexual development across the apicomplexa. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:698–711. doi: 10.1128/EC.00021-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xia D, Sanderson SJ, Jones AR, Prieto JH, et al. The proteome of Toxoplasma gondii: integration with the genome provides novel insights into gene expression and annotation. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R116. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexander DL, Mital J, Ward GE, Bradley P, Boothroyd JC. Identification of the moving junction complex of Toxoplasma gondii: a collaboration between distinct secretory organelles. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Straub KW, Cheng SJ, Sohn CS, Bradley PJ. Novel components of the Apicomplexan moving junction reveal conserved and coccidia-restricted elements. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:590–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexander DL, Arastu-Kapur S, Dubremetz JF, Boothroyd JC. Plasmodium falciparum AMA1 binds a rhoptry neck protein homologous to TgRON4, a component of the moving junction in Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1169–1173. doi: 10.1128/EC.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Besteiro S, Michelin A, Poncet J, Dubremetz JF, Lebrun M. Export of a Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry neck protein complex at the host cell membrane to form the moving junction during invasion. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000309. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu JH, Qin ZH, Liao YS, Xie MQ, et al. Characterization and expression of an actin-depolymerizing factor from Eimeria tenella. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0961-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fetterer RH, Miska KB, Jenkins MC, Barfield RC. A conserved 19-kDa Eimeria tenella antigen is a profilin-like protein. J Parasitol. 2004;90:1321–1328. doi: 10.1645/GE-307R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferguson DJ, Birch-Andersen A, Hutchinson WM, Siim JC. Light and electron microscopy on the sporulation of the oocysts of Eimeria brunetti. II. Development into the sporocyst and formation of the sporozoite. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [B] 1978;86:13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pomel S, Luk FC, Beckers CJ. Host cell egress and invasion induce marked relocations of glycolytic enzymes in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000188. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allocco JJ, Profous-Juchelka H, Myers RW, Nare B, Schmatz DM. Biosynthesis and catabolism of mannitol is developmentally regulated in the protozoan parasite Eimeria tenella. J Parasitol. 1999;85:167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allocco JJ, Nare B, Myers RW, Feiglin M, et al. Nitrophenide (Megasul) blocks Eimeria tenella development by inhibiting the mannitol cycle enzyme mannitol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase. J Parasitol. 2001;87:1441–1448. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[1441:NMBETD]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukata T, Sasai K, Arakawa A, McDougald LR. Penetration of Eimeria tenella sporozoites under different oxygen concentrations in vitro. J Parasitol. 1992;78:537–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beyer TV. Coccidia of domestic animals. Some metabolic peculiarities of particular stages of the life cycle. J Parasitol. 1970;56:28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Labbe M, Peroval M, Bourdieu C, Girard-Misguich F, Pery P. Eimeria tenella enolase and pyruvate kinase: a likely role in glycolysis and in others functions. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1443–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schaap D, Arts G, van Poppel NF, Vermeulen AN. De novo ribosome biosynthesis is transcriptionally regulated in Eimeria tenella, dependent on its life cycle stage. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;139:239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferguson DJ, Campbell SA, Henriquez FL, Phan L, et al. Enzymes of type II fatty acid synthesis and apicoplast differentiation and division in Eimeria tenella. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:33–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pal-Bhowmick I, Vora HK, Jarori GK. Sub-cellular localization and post-translational modifications of the Plasmodium yoelii enolase suggest moonlighting functions. Malar J. 2007;6:45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gomes RA, Vicente Miranda H, Sousa Silva M, Graca G, et al. Protein glycation and methylglyoxal metabolism in yeast: finding peptide needles in protein haystacks. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008;8:174–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carruthers VB, Tomley FM. Microneme proteins in apicomplexans. Subcell Biochem. 2008;47:33–45. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78267-6_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sibley LD. Intracellular parasite invasion strategies. Science. 2004;304:248–253. doi: 10.1126/science.1094717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.