Abstract

Polymorphisms in the IL28B gene region are important in predicting outcome following therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. We evaluated the role of IL28B in spontaneous and treatment-induced clearance following recent HCV infection. The Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C was a study of the natural history and treatment of recent HCV, as defined by positive anti-HCV antibody, preceded by either acute clinical HCV infection within the prior 12 months or seroconversion within the prior 24 months. Factors associated with spontaneous and treatment-induced HCV clearance, including variations in IL28B, were assessed. Among 163 participants, 132 were untreated (n=52) or had persistent infection (infection duration ≥26 weeks) at treatment initiation (n=80). Spontaneous clearance was observed in 23% (30 of 132). In Cox proportional hazards analysis (without IL28B), HCV seroconversion illness with jaundice was the only factor predicting spontaneous clearance (AHR 2.86, 95% CI, 1.24, 6.59, P=0.014). Among participants with IL28B genotyping (n=102/163 overall and 79/132 for spontaneous clearance population), rs8099917 TT homozygosity (vs GT/GG) was the only factor independently predicting time to spontaneous clearance (AHR 3.78, 95% CI, 1.04, 13.76, P=0.044). Participants with seroconversion illness with jaundice were more frequently rs8099917 TT homozygotes than other (GG/GT) genotypes (32% versus 5%, P=0.047). Among participants adherent to treatment and had IL28B genotyping (n=54), SVR was similar among TT homozygotes (18/29, 62%) and those with GG/GT genotype (16/25, 64%, P=0.884).

Conclusion

During recent HCV, genetic variations in IL28B region were associated with spontaneous but not treatment-induced clearance. Early therapeutic intervention could be recommended for individuals with unfavorable IL28B genotypes.

Keywords: host genetics, spontaneous clearance, sustained virological response, pegylated interferon, acute

Following hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, spontaneous viral clearance occurs in 25% of individuals, generally within the initial six months (1). Although treatment for acute HCV infection enhances viral clearance (2, 3), delayed commencement may impair response (4). Understanding factors that predict spontaneous and treatment-induced acute HCV clearance would improve clinical decision making around early therapeutic intervention.

Spontaneous HCV clearance is likely dependent on both host and pathogen-related factors. However, female gender is the only readily identifiable factor consistently associated with spontaneous clearance in prospective studies of acute HCV infection (1, 5, 6). It is also clear that a strong, broad host immune response to HCV is important for spontaneous clearance (7-10).

Genome-wide association studies have demonstrated that genetic variations in the region near the interleukin-28B (IL28B) gene, which encodes interferon-λ3 (IFN-λ3), are associated with chronic HCV treatment response (11-14). In one candidate gene study (15) and one genome-wide association study (14), it was demonstrated that genetic variations in the IL28B gene region are also associated with absence of HCV RNA in anti-HCV antibody positive individuals (presumed spontaneous HCV clearance). However, studies performed to date are limited to chronic infection, lack longitudinal data to enable an examination of the effects of genetic variations in the IL28B gene region on the time to spontaneous HCV clearance and are cross-sectional in nature.

We investigated the effect of genetic variations in the IL28B gene region on time to spontaneous HCV clearance and treatment-response following recent HCV infection in the Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C (ATAHC), a prospective trial of the natural history and treatment of recently acquired HCV infection.

Methods

Study design

ATAHC was a multicenter, prospective cohort study of the natural history and treatment of recent HCV infection, as previously described (3). Recruitment of HIV infected and HIV uninfected participants was from June 2004 through November 2007. Recent infection with either acute or early chronic HCV infection with the following eligibility criteria: First positive anti-HCV antibody within 6 months of enrolment; and either

Acute clinical hepatitis C infection, defined as symptomatic seroconversion illness or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal (>400 IU/mL) with exclusion of other causes of acute hepatitis, at most 12 months before the initial positive anti-HCV antibody; or

Asymptomatic hepatitis C infection with seroconversion, defined by a negative anti-HCV antibody in the two years prior to the initial positive anti-HCV antibody.

All participants with detectable HCV RNA during the screening period (maximum 12 weeks) were assessed for HCV treatment eligibility. Participants unwilling to undergo treatment assessment and those with undetectable HCV RNA at screening continued to be followed. From screening, participants were followed for up to 12 weeks to allow for spontaneous HCV clearance and if HCV RNA remained detectable were offered treatment. Participants were then seen at baseline and 12 weekly intervals for up to 144 weeks (individuals receiving HCV treatment were also seen at 4-weekly intervals up to week 12).

All study participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (primary study committee) as well as through local ethics committees at all study sites. The study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov registry (NCT00192569).

HCV treatment

Participants who began HCV treatment received pegylated interferon-α2a (PEG-IFN) 180 ug weekly for 24 weeks. Due to non-response at week 12 in the initial two participants with HCV/HIV coinfection, the study protocol was amended to provide PEG-IFN and ribavirin combination therapy for 24 weeks in this group. Ribavirin was prescribed at a dose of 1000-1200 mg for those with genotype 1 and 800 mg in those with genotype 2/3.

Detection and quantification of HCV RNA

HCV RNA assessment was performed at all scheduled study visits, initially with a qualitative HCV-RNA assay (TMA assay, Versant, Bayer, Australia, lower limit of detection 10 IU/ml) and if detectable repeated on a quantitative assay (Versant HCV RNA 3.0 Bayer, Australia lower limit of detection 615 IU/ml). HCV genotype (Versant LiPa2, Bayer, Australia) was performed on all participants with detectable HCV RNA at screening.

IL28B genotyping

Two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified in previous genome-wide association studies (rs8099917 and rs12980275) in the IL28A and B gene region were genotyped for all participants in whom DNA was available. These two SNPs were genotyped in the Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX genotyping platform. One other major SNP in the IL28A and B gene region, rs12979860, has been identified in previous genome-wide association studies. Sequencing of rs12979860 was performed by Sanger sequencing with the following primers: forward primer: 3’-CTGGGATTCCTGGACGTG-5’, reverse primer: 3’-GTTCCCATACACCCGTTCC-5’ and sequencing primer: 3’-TGGACGTGGATGGGTACTG-5’. The PCR conditions are as follows: one cycle of 96°C for 10 min; 5 cycles of 96°C for 30 sec, 64°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec; 30 cycles of 96°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec; one cycle of 72°C for 5 min and hold at 4°C.

Study definitions

The presentation of recent HCV infection was classified as either acute clinical or asymptomatic infection. Acute clinical infection included those with either a documented clinical history of symptomatic seroconversion illness and those without clinical symptoms but with a documented peak ALT above 400 IU/ml at or prior to the time of diagnosis. Participants with asymptomatic infection included participants with anti-HCV antibody seroconversion but no acute clinical symptoms or documented peak ALT above 400 IU/ml.

Study outcomes

In the present analysis, participants with spontaneous HCV clearance were identified (two undetectable HCV RNA tests (<10 IU/mL), ≥4 weeks apart) and compared to participants without clearance (untreated participants and treated participants with an estimated duration of infection of ≥26 weeks). The estimated date of viral clearance was defined as the midpoint between the first of two consecutive undetectable qualitative HCV RNA samples and either the last sample with detectable HCV RNA (16) or the estimated date of infection, in the event that the sample collected at screening was undetectable for HCV RNA. Participants with only one undetectable HCV RNA as their last measurement were not considered to have achieved spontaneous HCV clearance and were censored at last HCV RNA test.

Evaluation of HCV treatment response was based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses that included all participants who received at least one injection of PEG-IFN therapy. Additional analyses included all adherent individuals (received at least 80% of scheduled treatment). Primary endpoints for treatment were the proportion of participants with undetectable qualitative HCV RNA rates at weeks 4 (rapid virological response, RVR) and 48 (sustained virological response, SVR).

Statistical analyses

Spontaneous clearance rates were calculated using person-time of observation and confidence intervals (CI) for the rates were calculated using a Poisson distribution. Cox proportional hazards analyses were used to identify factors associated with spontaneous HCV clearance. Potential predictors were determined a priori and included sex, age, injecting drug use characteristics, methadone or buprenorphine treatment, estimated duration of HCV infection, HCV seroconversion illness (with jaundice), peak ALT level, HIV infection and HCV genotype. A backwards stepwise approach was utilised, considering factors that were significant at the 0.20 level in univariate analysis. All final multivariate models included only factors that remained significant at the 0.05 level.

We hypothesized that during recent HCV infection, IL28B genotype would be associated with spontaneous HCV clearance, but not treatment-induced clearance, given the higher SVR observed during PEG-IFN treatment for acute HCV infection when compared to chronic infection (17-20). The effects of the two SNPs (rs12980275 and rs8099917) near the IL28B gene on time to spontaneous HCV clearance were assessed by Kaplan Meier and Cox proportional hazards analyses. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were determined using a backwards stepwise approach, considering IL28B genotype and factors that were associated with spontaneous HCV clearance in the overall population. Logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate factors associated with acute symptomatic HCV infection with jaundice. Potential predictors included sex, age, mode of HCV acquisition, HIV infection, HCV genotype and IL28B genotype. The effects of the two SNPs on HCV treatment response were also evaluated. This included stratified analyses to assess the effect of the two SNPs while adjusting for HIV infection and HCV genotype. All analyses were performed using the statistical package Stata (version 10.1). Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and linkage disequilibrium were calculated by Haploview version 3 (21).

Results

A total of 163 participants were enrolled in the ATAHC study (Figure 1). The mean age was 34 years (SD, 9.9), the majority were male (72%), 91% were Caucasian and 31% were co-infected with HIV. Injection drug use was the predominant mode of acquisition (n=119, 73%), followed by male to male sexual contact (n=24, 15%).

Figure 1.

Overview of study population

Diagnosis of recent HCV infection was based on acute clinical hepatitis in 61% (99 of 163), that included symptomatic seroconversion illness in 41% (67 of 163, including 36 with jaundice) and ALT >400 IU/mL in 20% (32 of 163), respectively. Diagnosis of recent HCV infection was based on anti-HCV antibody seroconversion in the absence of an acute clinical presentation in 39% (64 of 163).

Among 163 participants, 132 were either untreated (n=52) or had chronic infection (persistent HCV viraemia and estimated duration of infection ≥26 weeks) at the time of treatment initiation (n=80) and formed the study population in which spontaneous clearance was assessed (Figure 1). Initially, factors associated with spontaneous viral clearance without incorporation of IL28B genotyping data were examined in this population. Spontaneous clearance was observed in 23% (30 of 132), and the estimated rate of clearance at 12 months was 27.1% (95% CI: 17.7, 39.7). In multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses, acute HCV seroconversion illness with jaundice was the only factor associated with time to spontaneous clearance (AHR 2.86, 95% CI, 1.24, 6.59, P=0.014, Table 1).

Table 1.

Cox proportional hazards analysis of factors associated with spontaneous HCV clearance during recent infection, excluding treated participants with an estimated duration of infection <26 weeks (n=132).

| Characteristic | Hazards Ratio | 95% | CI | P | Adjusted Hazards Ratio | 95% | CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs), mean/SD | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Age category/10 years | 0.87 | 0.59 | 1.28 | 0.470 | - | - | - | - |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | - | - | - | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| Female | 1.04 | 0.48 | 2.22 | 0.925 | 1.23 | 0.56 | 2.68 | 0.601 |

| Injecting drug use | ||||||||

| Not injected in last 6 months | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Injected in last 6 months | 0.81 | 0.30 | 2.22 | 0.689 | - | - | - | - |

| Never injected | 0.70 | 0.19 | 2.62 | 0.598 | - | - | - | - |

| Methadone or buprenorphine treatment | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 1.31 | 0.49 | 3.49 | 0.584 | - | - | - | - |

| Presentation of recent HCV | ||||||||

| Asymptomatic seroconversion | 1.00 | - | - | - | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| Acute clinical (no jaundice) | 0.90 | 0.30 | 2.71 | 0.845 | 0.90 | 0.30 | 2.71 | 0.846 |

| Acute clinical (with jaundice) | 2.75 | 1.21 | 6.24 | 0.016 | 2.86 | 1.24 | 6.59 | 0.014 |

| Estimated duration of infection (wks)* | ||||||||

| < 26 weeks | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ≥ 26 weeks | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.87 | 0.020 | - | - | - | - |

| Peak ALT prior to enrolment (IU/L) | ||||||||

| ≤ 400 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| > 400 | 1.79 | 0.85 | 3.78 | 0.127 | - | - | - | - |

| HIV infection | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 0.83 | 0.35 | 1.92 | 0.657 | - | - | - | - |

| HCV genotype | ||||||||

| Genotype 1,4 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Genotype 2/3 | 0.93 | 0.28 | 3.07 | 0.909 | - | - | - | - |

| Missing | 20.79 | 7.58 | 57.03 | 0.000 | - | - | - | - |

Data on IL28B polymorphisms at rs8099917, rs12980275 and rs12979860 was available for 102/163,100/163 and 76/163 participants, respectively. Given that rs8099917 and rs12980275 are in linkage disequilibrium with rs12979860 (11), analyses were subsequently performed using the SNPs rs8099917 and rs12980275 (Figure 1). Both of the SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium in this population (p=1.0). Participants with and without IL28B genotyping were similar, including age, gender, acute symptomatic illness, HCV genotype distribution and treated proportion (see supplementary Table). To evaluate the impact of genetic variation in the IL28B gene on time to spontaneous clearance, Kaplan Meier analyses were performed. Among participants with genotyping at rs8099917 (n=79/132), T homozygotes (vs GT/GG) had increased spontaneous clearance (P=0.021, Figure 2A). None of the rs8099917 G homozygotes (n=4) demonstrated spontaneous clearance. Among participants with genotyping at rs12980275 (n=75/132), spontaneous clearance was similar among those with AA genotype as compared to G carriers (P=0.78, Figure 2B). However, none of the G homozygotes at rs12980275 (n=7) demonstrated spontaneous clearance.

Figure 2.

A. Time to spontaneous HCV clearance among participants with GG/GT and TT genotypes at the SNP rs8099917 in the IL28B gene in the ATAHC study, excluding treated participants with an estimated duration of infection <26 weeks (n=79).

B. Time to spontaneous HCV clearance among participants with GG/GA and AA genotypes at the SNP rs12980275 in the IL28B gene in the ATAHC study, excluding treated participants with an estimated duration of infection <26 weeks (n=75).

Among participants with genotyping at rs8099917 (n=79/132), the proportions with spontaneous HCV clearance were 0% (0 of 4), 11% (3 of 28) and 32% (15 of 47) in those with the GG, GT and TT genotypes, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1). Among participants with genotyping at rs12980275 (n=75/132), the proportions with spontaneous HCV clearance were 0% (0 of 7), 26% (8 of 31) and 22% (8 of 37) in those with the GG, GA and AA genotypes, respectively.

In univariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, rs8099917 TT genotype was associated with time to spontaneous clearance (vs. GG/GT, AHR 4.32, 95% CI, 1.24, 15.01, P=0.021), while rs12980275 AA genotype was not associated (vs. GG/GA AHR 1.15, 95% CI, 0.43, 3.08, P=0.781). In multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis (Table 2), after adjusting for female sex (AHR 1.81, 95% CI, 0.67, 4.85, P=0.241) and acute HCV seroconversion illness with jaundice (AHR 1.72, 95% CI, 0.54, 5.51, P=0.361), rs8099917 TT genotype (vs. GG/GT) was the only factor predicting time to spontaneous clearance (AHR 3.78, 95% CI, 1.04, 13.76, P=0.044).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis of the association of rs8099917 genotypes with spontaneous HCV clearance, adjusted for sex and symptomatic infection, during recent infection, excluding treated participants with an estimated duration of infection <26 weeks.

| Covariate | AHR | 95% | CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| Female | 1.81 | 0.67 | 4.85 | 0.241 |

| Presentation of recent HCV | ||||

| Asymptomatic seroconversion | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| Acute clinical (no jaundice) | 0.85 | 0.25 | 2.84 | 0.788 |

| Acute clinical (with jaundice) | 1.72 | 0.54 | 5.51 | 0.361 |

| IL28B genotype | ||||

| rs8099917 | ||||

| GG/GT | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| TT | 3.78 | 1.04 | 13.76 | 0.044 |

Given rs8099917 genotype was the only independent factor associated with spontaneous clearance, we hypothesized that TT genotype would be associated with acute HCV seroconversion illness with jaundice. Acute HCV seroconversion illness (with jaundice) was greater among T homozygotes compared to those with the GG/GT genotype (32% versus 5%, P=0.047, Table 3). With this in mind, we evaluated factors associated with acute HCV seroconversion illness with jaundice. In univariate logistic regression analyses, acute HCV seroconversion illness with jaundice was not associated with sex, age, HIV status, HCV genotype or mode of HCV acquisition, but was associated with both rs8099917 genotype [TT vs. GG/GT, P=0.005, OR=8.60, 95% CI=1.88- 39.28) and rs12980275 genotype (AA vs. GG/GA, P=0.008, OR=4.46, 95% CI=1.49-13.39).

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants with the rs8099917 TT and GT/GG genotypes among those with available genotype testing.

| Characteristic | Overall (n=102) | GG/GT (n=39) | % | TT (n=63) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 74 | 29 | 74% | 45 | 71% |

| Female | 28 | 10 | 26% | 18 | 29% |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 92 | 34 | 87% | 58 | 92% |

| Other | 10 | 5 | 13% | 5 | 8% |

| Presentation of recent HCV | |||||

| Asymptomatic seroconversion | 55 | 27 | 69% | 28 | 44% |

| Acute clinical (no jaundice) | 23 | 9 | 23% | 14 | 22% |

| Acute clinical (with jaundice) | 22 | 2 | 5% | 20 | 32% |

| Peak ALT prior to enrolment (IU/L) | |||||

| ≤ 400 | 37 | 21 | 54% | 16 | 25% |

| > 400 | 60 | 15 | 38% | 45 | 71% |

Among participants treated for HCV (n=111), 54 were adherent to therapy and had available rs8099917 IL28B genotyping. Among those with week 4 HCV RNA testing (n=51), 35% (8 of 23) of those with the rs8099917 GG or GT genotype demonstrated RVR as compared to 57% (16 of 28) of those with the TT genotype (P=0.160). However, rs8099917 genotype had no impact on SVR (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 2). Further, genetic variations in rs8099917 did not have any impact on SVR when stratified by HIV infection/regimen or HCV genotype. SVR was 50% and 69% for HIV uninfected subjects with rs8099917 GG/GT (n=16) and TT (n=16) genotypes, respectively (P=0.280), and 89% and 54% for HIV infected subjects with rs8099917 GG/GT (n=9) and TT (n=13) genotypes, respectively (P=0.165). SVR was 57% and 61% for HCV genotype 1/4 subjects with rs8099917 GG/GT (n=14) and TT (n=23) genotypes, respectively (P=0.999), and 73% and 67% for HCV genotype 2/3 subjects with rs8099917 GG/GT (n=11) and TT (n=6) genotypes, respectively (P=0.999). Among adherent participants with genotyping at rs8099917 (n=54), the proportions with SVR were 100% (3 of 3), 59% (13 of 22) and 62% (18 of 29) in those with the GG, GT and TT genotypes, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2). Among adherent participants with genotyping at rs12980275 (n=57), the proportions with spontaneous HCV clearance were 100% (4 of 4), 48% (12 of 25) and 64% (18 of 28) in those with the GG, GA and AA genotypes, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Proportion with SVR among participants adherent to therapy with rs8099917 and rs12980275 genotyping.

The proportion of participants with the rs8099917 GG, GT and TT genotypes were 0%, 17% and 83% in those with spontaneous HCV clearance, 9%, 38% and 53% among adherent participants with treatment-induced clearance and 0%, 45% and 55% in those without treatment response. Carriage of the risk G allele was identified in 17% of participants with spontaneous clearance, 47% of those with treatment-induced clearance and 45% of those without treatment response.

DISCUSSION

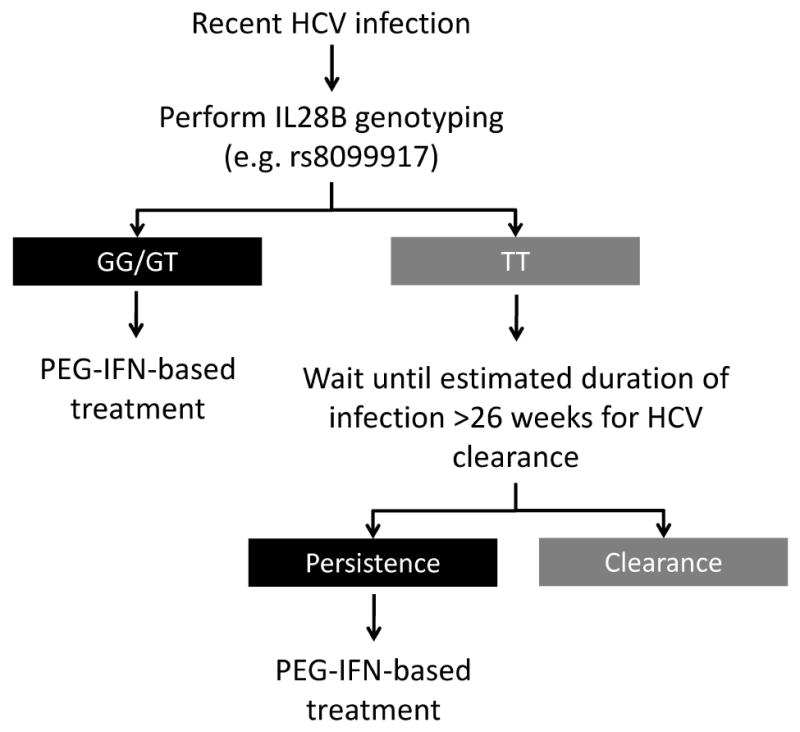

In our study of recent HCV infection, genetic variation in the IL28B gene was associated with both spontaneous HCV clearance and acute symptomatic HCV infection with jaundice. However, genetic variation in the IL28B gene did not impact response to treatment during recent HCV infection. This study of the impact of genetic variation in the IL28B gene on spontaneous and treatment-induced clearance in recent HCV infection provides both greater understanding of the impact of IL28B on HCV viral control and broadens the potential clinical utility of host genotyping. Individuals with unfavourable IL28B genotype (rs8099917 GG/GT) could be more strongly recommended for early therapeutic intervention for acute HCV infection, given their low likelihood of spontaneous clearance but non-compromised IFN-based therapeutic outcome (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proposed algorithm for incorporation of IL28B genetic testing into clinical management of acute HCV infection.

Genetic variation in the IL28B gene was associated with spontaneous clearance, after adjusting for gender and acute symptomatic HCV infection with jaundice. This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that IL28B genotype is associated with undetectable HCV RNA in anti-HCV antibody positive individuals with presumed spontaneous clearance (14, 15). In one candidate gene study, Thomas et al demonstrated that participants who were homozygous for the C allele at rs12979860 had greater odds of spontaneous HCV clearance (15). Further, data from a large genome-wide association study demonstrated that the rs8099917 SNP in the IL28B gene is the strongest common human genetic determinant for spontaneous clearance (14).

The mechanism and explanation behind the association of genetic variations in the IL28B gene and spontaneous clearance may be related to the host innate immune response. IL28B encodes IFN-λ-3, which is involved in viral control, including HCV (22). Both IFN-α and IFN-λ-3 bind to cell-surface receptors and activate the JAK-STAT cell-signaling cascade leading to the induction of interferon stimulating genes (ISGs), a mechanism by which IFNs suppress viral infections (22-24). In addition, data demonstrating that IL28B is associated with treatment response in the setting of chronic HCV infection (11-14) suggests that IFN-λ-3 is not simply an alternate means of inducing the JAK-STAT pathway. This is supported by data demonstrating that in vitro, IFN-α induces expression of IFN-λ genes (24), IFN-λ inhibits HCV replication through a signal transduction/ISG pathway distinct from that of IFN-α (22) and that either low-dose IFN-α or IFN-λ can enhance the anti-HCV activity of the other (22). Collectively, these data suggest that IFN-λ is involved in the early host innate immune response to HCV and may explain the observed effect on spontaneous clearance.

Genetic variation in the IL28B gene was not associated with response to treatment for recent HCV infection, irrespective of treatment regimen/HIV infection or HCV genotype. This is in contrast to chronic HCV, where human IL28B genotype is associated with response to PEG-IFN-alfa/ribavirin treatment (11-14). In Ge et al, the strongest association with treatment-induced clearance was the SNP rs12979860 (CC genotype), but there was suggestive evidence for an independent effect at rs8099917 (11). In Suppiah et al, individuals with the TT genotype (compared to GG/GT) at rs8099917 were two times more likely to achieve an SVR following HCV treatment (12). A further genome-wide association study demonstrating rs8099917 as the strongest common human genetic determinant for treatment-induced clearance (14). The absence of an observed effect of IL28B and response to treatment for early HCV infection is not surprising, given the higher SVR observed during PEG-IFN treatment for acute HCV infection when compared to chronic infection (17-20). Participants with an unfavorable IL28B genotype (GG/GT) who did not achieve an RVR were able to achieve continued HCV RNA decline during HCV therapy, allowing them to achieve a similar rate of SVR as those with the favorable IL28B genotype (TT).

Genetic variation in the IL28B gene (both SNPs rs8099917 and rs12980275) was also associated with jaundice. This is consistent with the observation that the inclusion of IL28B in adjusted models to evaluate time to HCV clearance abolished the effect of acute HCV seroconversion illness with jaundice. Further studies are required to understand the mechanism behind this association.

A major limitation of this study is the small sample size and heterogeneity among participants assessed for IL28B and treatment-induced clearance. Larger studies are required to further assess the impact of HIV status and HCV genotype, but it is worth noting that among HIV/HCV coinfected participants with the unfavourable rs8099917 IL28B GG/GT genotypes 8 of 9 achieved an SVR. A further limitation is lack of IL28B genotyping data on around one-third of participants, however, the populations with and without genotyping had similar demographic and clinical characteristics. Lastly, we did not have complete genotyping data on the SNP rs12979860, which has been identified in previous studies to be associated with spontaneous and treatment-induced HCV clearance.

The study findings have the potential to broaden the role of IL28B genetic testing in clinical practice. Individuals identified with acute or recent HCV infection who have rs8099917 TT genotype could have therapy deferred to allow for spontaneous clearance. In contrast, for individuals with rs809917 GG or GT genotypes, given the low likelihood of spontaneous clearance, non-compromised response to IFN-based therapy in recent HCV inferction, and lower likelihood of response to PEG-IFN and ribavirin therapy during chronic infection as compared to those with the TT genotype, we propose that treatment be initiated close to the time of clinical presentation. The feasibility of this approach is further justified given that among studies performed to date, a sizeable proportion of Caucasians (40%) carry unfavorable rs8099917 genotypes (GT or GG).

The discovery of the association of the impact of genetic variations in the IL28B gene has the potential to greatly enhance decision-making for chronic HCV. Our findings in the setting of recent HCV infection broaden the potential clinical utility of IL28B genetic testing.

Supplementary Material

Spontaneous HCV clearance among participants with genotyping at the SNPs rs8099917 (n=79) and rs12980275 (n=75) in the IL28B gene in the ATAHC study, excluding treated participants with an estimated duration of infection <26 weeks.

Sustained virological response among adherent participants with genotyping at the SNPs rs8099917 (n=54) and rs12980275 (n=57) in the IL28B gene in the ATAHC study.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant RO1 DA 15999-01. The National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales. Roche Pharmaceuticals supplied financial support for pegylated IFN–alfa-2a/ribavirin. GD, PH and AL were supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Research Fellowships. MH was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Award and a VicHealth Senior Research Fellowship. JGr was supported by Post Doctoral Fellowships from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Canadian Research Training Program in Hepatitis C. JK was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Research Fellowship.

Role of funding source The funding sources for the study (National Institutes of Health and Roche Pharmaceuticals) did not contribute to study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, and had no role in writing of the manuscript or decision to submit the paper for publication.

List of Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- IL28B

interleukin 28B

- IFN-λ3

interferon-λ3

- ATAHC

Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- PEG-IFN

pegylated interferon-α2a

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- ITT

intention-to-treat

- RVR

rapid virological response

- SVR

sustained virological response

- CI

confidence intervals

- AHR

adjusted hazards ratio

APPENDIX

ATAHC Study Group

Protocol Steering Committee members

John Kaldor (NCHECR), Gregory Dore (NCHECR), Gail Matthews (NCHECR), Pip Marks (NCHECR), Andrew Lloyd (UNSW), Margaret Hellard (Burnet Institute, VIC), Paul Haber (University of Sydney), Rose Ffrench (Burnet Institute, VIC), Peter White (UNSW), William Rawlinson (UNSW), Carolyn Day (University of Sydney), Ingrid van Beek (Kirketon Road Centre), Geoff McCaughan (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital), Annie Madden (Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League, ACT), Kate Dolan (UNSW), Geoff Farrell (Canberra Hospital, ACT), Nick Crofts (Nossal Institute, VIC), William Sievert (Monash Medical Centre, VIC), David Baker (407 Doctors).

NCHECR ATAHC Research Staff

John Kaldor, Gregory Dore, Gail Matthews, Pip Marks, Barbara Yeung, Jason Grebely, Brian Acraman, Kathy Petoumenos, Janaki Amin, Carolyn Day, Anna Doab, Therese Carroll.

Burnet Institute Research Staff

Margaret Hellard, Oanh Nguyen, Sally von Bibra.

Immunovirology Laboratory Research Staff

UNSW Pathology - Andrew Lloyd, Suzy Teutsch, Hui Li, Alieen Oon, Barbara Cameron.

SEALS – William Rawlinson, Brendan Jacka, Yong Pan.

Burnet Institute Laboratory, VIC – Rose Ffrench, Jacqueline Flynn, Kylie Goy.

Clinical Site Principal Investigators

Gregory Dore, St Vincent’s Hospital, NSW; Margaret Hellard, The Alfred Hospital, Infectious Disease Unit, VIC; David Shaw, Royal Adelaide Hospital, SA; Paul Haber, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital; Joe Sasadeusz, Royal Melbourne Hospital, VIC; Darrell Crawford, Princess Alexandra Hospital, QLD; Ingrid van Beek, Kirketon Road Centre; Nghi Phung, Nepean Hospital; Jacob George, Westmead Hospital; Mark Bloch, Holdsworth House GP Practice; David Baker, 407 Doctors; Brian Hughes, John Hunter Hospital; Lindsay Mollison, Fremantle Hospital; Stuart Roberts, The Alfred Hospital, Gastroenterology Unit, VIC; William Sievert, Monash Medical Centre, VIC; Paul Desmond, St Vincent’s Hospital, VIC.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Authors GJD, GVM, JMK designed the original ATAHC study and wrote the protocol. Authors GJD, GVM, JGr, KP, TA, JGe and VS designed the IL28B sub-study. Author JG drafted the primary statistical analysis plan, which was reviewed by KP, GJD, GVM, TA, and JGe. TA, VS, JGe, and DB coordinated IL28B genetic sequencing. The primary statistical analysis was conducted by KP and additional statistical analyses were conducted by JGr and GJD. All authors reviewed data analysis. Authors GJD and JGr wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures: GD, GM and JK have received research support from Roche Pharmaceuticals. GD is on the speaker’s bureau for Roche Pharmaceuticals. GD and GM are members of advisory board for Roche Pharmaceuticals. GD, PM and BY have received travel grants from Roche Pharmaceuticals. GD is a consultant/advisor for Schering Plough, Tibotec, and Abbott. JGr is a member of an advisory board for Schering-Plough. GM is a consultant/advisor for Schering Plough, Novartis and Astellar.

Contributor Information

Jason Grebely, Email: jgrebely@nchecr.unsw.edu.au.

Kathy Petoumenos, Email: kpetoumenos@nchecr.unsw.edu.au.

Margaret Hellard, Email: hellard@burnet.edu.au.

Gail Matthews, Email: gmatthews@nchecr.unsw.edu.au.

Vijayaprakash Suppiah, Email: vijay_suppiah@wmi.usyd.edu.au.

Tanya Applegate, Email: tapplegate@nchecr.unsw.edu.au.

Barbara Yeung, Email: byeung@nchecr.unsw.edu.au.

Phillipa Marks, Email: pmarks@nchecr.unsw.edu.au.

William Rawlinson, Email: w.rawlinson@unsw.edu.au.

Andrew R. Lloyd, Email: a.lloyd@unsw.edu.au.

David Booth, Email: david_booth@wmi.usyd.edu.au.

John M. Kaldor, Email: jkaldor@nchecr.unsw.edu.au.

Jacob George, Email: jacob.george@sydney.edu.au.

Gregory J. Dore, Email: gdore@nchecr.unsw.edu.au.

References

- 1.Micallef JM, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grebely J, Matthews GV, Petoumenos K, Dore GJ. Spontaneous clearance and the beneficial impact of treatment on clearance during recent hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dore GJ, Hellard M, Matthews GV, Grebely J, Haber PS, Petoumenos K, Yeung B, et al. Effective treatment of injecting drug users with recently acquired hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:123–135. e121–122. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamal SM, Fouly AE, Kamel RR, Hockenjos B, Al Tawil A, Khalifa KE, He Q, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b therapy in acute hepatitis C: impact of onset of therapy on sustained virologic response. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:632–638. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang CC, Krantz E, Klarquist J, Krows M, McBride L, Scott EP, Shaw-Stiffel T, et al. Acute hepatitis C in a contemporary US cohort: modes of acquisition and factors influencing viral clearance. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1474–1482. doi: 10.1086/522608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, Shiboski S, Lum P, Delwart E, Tobler L, et al. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution and reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1216–1226. doi: 10.1086/605947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diepolder HM. New insights into the immunopathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C. Antiviral Res. 2009;82:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.02.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Post J, Ratnarajah S, Lloyd AR. Immunological determinants of the outcomes from primary hepatitis C infection. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:733–756. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8270-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehermann B. Hepatitis C virus versus innate and adaptive immune responses: a tale of coevolution and coexistence. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1745–1754. doi: 10.1172/JCI39133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackard JT, Shata MT, Shire NJ, Sherman KE. Acute hepatitis C virus infection: a chronic problem. Hepatology. 2008;47:321–331. doi: 10.1002/hep.21902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, Heinzen EL, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, Bassendine M, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, Nakagawa M, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rauch A, Kutalik Z, Descombes P, Cai T, di Iulio J, Mueller T, Bochud M, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B Is Associated with Chronic Hepatitis C and Treatment Failure -A Genome-Wide Association Study. Gastroenterology. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, O’Huigin C, Kidd J, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amin J, Law MG, Micallef J, Jauncey M, Van Beek I, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. Potential biases in estimates of hepatitis C RNA clearance in newly acquired hepatitis C infection among a cohort of injecting drug users. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:144–150. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaeckel E, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, Santantonio T, Mayer J, Zankel M, Pastore G, et al. Treatment of acute hepatitis C with interferon alfa-2b. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1452–1457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiegand J, Buggisch P, Boecher W, Zeuzem S, Gelbmann CM, Berg T, Kauffmann W, et al. Early monotherapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2b for acute hepatitis C infection: the HEP-NET acute-HCV-II study. Hepatology. 2006;43:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamal SM, Ismail A, Graham CS, He Q, Rasenack JW, Peters T, Tawil AA, et al. Pegylated interferon alpha therapy in acute hepatitis C: relation to hepatitis C virus-specific T cell response kinetics. Hepatology. 2004;39:1721–1731. doi: 10.1002/hep.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamal SM, Moustafa KN, Chen J, Fehr J, Abdel Moneim A, Khalifa KE, El Gohary LA, et al. Duration of peginterferon therapy in acute hepatitis C: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2006;43:923–931. doi: 10.1002/hep.21197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcello T, Grakoui A, Barba-Spaeth G, Machlin ES, Kotenko SV, MacDonald MR, Rice CM. Interferons alpha and lambda inhibit hepatitis C virus replication with distinct signal transduction and gene regulation kinetics. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1887–1898. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:967–972. doi: 10.1038/nature04082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siren J, Pirhonen J, Julkunen I, Matikainen S. IFN-alpha regulates TLR-dependent gene expression of IFN-alpha, IFN-beta, IL-28, and IL-29. J Immunol. 2005;174:1932–1937. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Spontaneous HCV clearance among participants with genotyping at the SNPs rs8099917 (n=79) and rs12980275 (n=75) in the IL28B gene in the ATAHC study, excluding treated participants with an estimated duration of infection <26 weeks.

Sustained virological response among adherent participants with genotyping at the SNPs rs8099917 (n=54) and rs12980275 (n=57) in the IL28B gene in the ATAHC study.