Abstract

Objectives

Preimplantation factor (PIF) is a novel embryo-derived peptide which influences key processes in early pregnancy implantation, including immunity, adhesion, remodeling and apoptosis. Herein, we explore the effects of synthetic PIF (sPIF) on trophoblast invasion.

Methods

Invasion patterns of immortalized cultured HTR-8 trophoblast cells were analyzed through Matrigel extracellular matrix +/− sPIF (25–100nM) in a transwell assay. Effects were compared with epidermal growth factor (EGF) 10μg/mL, scrambled aminoacid sequence of PIF, or media alone as controls.

Results

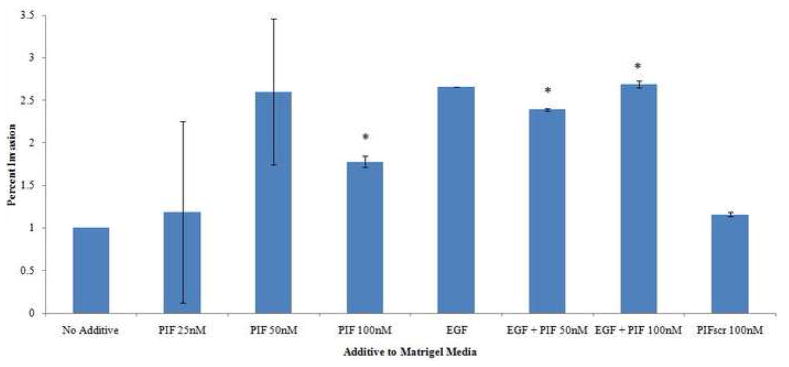

sPIF enhances trophoblast invasion at physiologic doses [at 50nM 260% (174–346% 95%CI, p=0.05); 100nM 178% (170–184%, p<0.02)], compared to scrambled amnioacid sequence PIF or control media. EGF added to sPIF does not further enhance trophoblast invasion [sPIF 50nM+EGF, 238% (237–239%, p<0.03); sPIF 100nM+EGF 269% (265–273%, p<0.04)].

Conclusion

PIF should be further investigated as it shows a potential preventative or therapeutic role for pregnancy complications associated with inadequate trophoblast invasion.

Keywords: First Trimester Trophoblast, Preimplantation factor, Trophoblast invasion

Introduction

Embryo implantation into maternal endometrium and placental formation with trophoblast invasion require a complex interplay of embryo-derived cell signaling for establishing maternal immune receptivity.1,2 This interplay was variously described over time by in vivo and in vitro models, and appears to involve initial polarization of the blastocyst, followed by cytokine signaling by IL-6, VEGF, and EGF among others.3–6 From the maternal side, immune acceptance and endometrial remodeling is characterized by recruitment of immune cells including natural killer cells, T regulatory cells, dendritic cells and macrophages, as well as uterine stromal cell decidualization.7 Implantation quality and depth of placental invasion has been positively correlated with overall pregnancy well being, and inversely correlated with adverse outcomes including intrauterine fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia and miscarriage.4 Ideally, a compound that could promote or ‘rescue’ placental invasion would represent a significant advance in reproductive technology.

We have identified a novel embryo-secreted peptide, preimplantation factor (PIF), (MVRIKPGSANKPSDD) secreted only by viable embryos, and absent in non-viable ones. PIF is detected early on and throughout pregnancy in the circulation of several species of pregnant mammals and is expressed in the placenta.8,9 Synthetic PIF (sPIF), structurally identical to native PIF, replicates PIF action, modulates peripheral immune cells and creates a favorable immune environment shortly after fertilization. We recently reported that sPIF displays essential multi-targeted effects promoting implantation.10 In human decidual cultures, sPIF regulates immunity, promotes embryo-decidual adhesion, and controls adaptive apoptotic processes.

In this study, we explore sPIF’s ability to promote trophoblast invasion, a critical step in successful mammalian reproduction. We hypothesized that sPIF would exert a positive autocrine effect on trophoblast invasion in addition to its previously demonstrated paracrine effect on the maternal decidua, further supporting placental development. We planned to compare the effect on trophoblast invasion to epidermal growth factor, another molecule which has been shown to promote implantation in the decidual and trophoblastic layers. 11,12

Materials and Methods

Peptide synthesis

Synthetic PIF (MVRIKPGSANKPSDD) and scrambled PIF (PIFscr) (GRVDPSNKSMPKDIA) were produced using solid-phase peptide synthesis (Peptide Synthesizer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) employing Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl) chemistry. Final purification was carried out by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), and peptide identities were verified by mass spectrometry (BioSynthesis, Lewisville, Tx).

Trophoblast in vitro transwell invasion assay

Immortalized first trimester extravillous cytotrophoblast HTR-8/SVneo cells (kindly provided by Dr. Charles Graham) were cultured on Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) coated wells as previously described.13,14 Trophoblast cells (2 ×105) were incubated for 24 hours with sPIF at 25–100nM. These concentrations of sPIF were chosen since we found that PIF is present at 50–150 ng/ml (30–100 nM) concentrations in the circulation of pregnant women, and sPIF is effective at modulating several decidual cell functions in the same concentration range.10 Epidermal growth factor (EGF) at a concentration of 10μg/mL, chosen due to its potent chemotactic effect at this dose in previous trials of EGF, was added to wells including sPIF at all concentrations as a positive control.11 Results were compared in parallel to exposure to PIFscr or to media alone (both used as negative controls). Cell culture inserts with porous membrane [8 um pore size, 6.5 mm diameter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA)] were coated with Matrigel extracellular matrix as per the manufacturer’s instructions for 1 hour. The porous inserts were cultured in a 24-well dish containing 600 μL of RPMI 1640 complete medium for 24 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. The inserts were removed, washed with phosphate buffered saline, and the non-invading cells as well as residual Matrigel were removed from the membranes by aspirating the media as well as using a cotton tip applicator. The membranes were treated with Colorimetric nuclear stain (Chemicon International, Billerica, MA) and washed several times. The membranes were excised from the transwells, and placed on a glass slide with the downside of the filter facing up. For quantification, the cells on the lower surface of the filter were counted under a microscope at 40× magnification. Trophoblast invasion was analyzed from three independent replicates. Results were quantified as percent invasion of number of trophoblast through Matrigel in an individual media milieu relative to invasion of trophoblast through Matrigel alone without media additive in the same experiment set. Statistical analysis was performed comparing the means of three experiments using multiple paired two-tailed t-tests and ANOVA, P<0.05 was considered as statically significant. As no human tissues were used during these experiments, IRB approval was not obtained for this project.

Results

sPIF promotes trophoblast migration

sPIF exerted a significant stimulatory effect on trophoblast invasion, in concentrations mimicking physiologic circulating maternal levels. The maximal effect, namely greater than two-fold increase, was noted at 50nM [260% (174–346% 95%CI, p=0.05)] while a higher dose at 100nM was slightly lower though with increased significance [178% (170–184%, p<0.02)]. (Table 1, Figure 1) Of note, there was no significant difference between migration noted at 50nM vs. 100nM when compared to eachother via ANOVA (p=0.178). At 25nM, the lowest concentration administered, and below the physiologic concentration range, sPIF’s effect was not significant. Testing of scrambled PIF (PIFscr) 100nM, used as a control, was not expected to have any biologic effect, and indeed did not affect trophoblast invasion.

Table 1.

Trophoblast Invasion, Relative to No Additive Value

Percent invasion of trophoblast cells through Matrigel extracellular matrix with associated media additive, relative to invasion without media additive. Confidence intervals and p-values provided. n=3 independent experiments

| Additive | Percent Invasion | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Additive | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| sPIF 25nM | 1.19 | 0.13 | 2.25 | 0.77 |

| sPIF 50nM | 2.6 | 1.74 | 3.46 | 0.05 |

| sPIF 100nM | 1.78 | 1.70 | 1.84 | (*) 0.02 |

| EGF 10μg | 2.66 | 0.00 | 11.32 | 0.46 |

| EGF 10μg + sPIF 50nM | 2.39 | 2.37 | 2.39 | (*) 0.03 |

| EGF 10μg + sPIF 100nM | 2.69 | 2.65 | 2.73 | (*) 0.04 |

| PIFscr 100nM | 1.16 | 1.14 | 1.18 | 0.28 |

Figure 1.

Percent invasion of trophoblast cells through Matrigel extracellular matrix with associated media additive. (Error bar not shown for EGF given width of confidence interval would skew visibility of other results).

EGF does not potentiate sPIF effect

To determine whether sPIF activity would be further enhanced by addition of a known promoter of trophoblast invasion and decidual receptivity, we added EGF in a previously reported fixed concentration to various sPIF doses tested on trophoblast invasion. We found that while sPIF’s effect was maximal at the 50nM dose, addition of EGF (10μg/mL) led to an insignificant decrease in trophoblast invasion as compared with sPIF alone [238% (237–239%, p<0.03 compared to media alone, p=0.470 compared to sPIF)]. At the higher concentration of sPIF100nM, added EGF led to an increase in trophoblast invasion, though again insignificant as compared to sPIF [269% (265–273%, p<0.04 compared to media alone, p=0.055 compared to sPIF)]. EGF alone had a positive albeit insignificant effect, similar in magnitude to the effect obtained using low dose sPIF [EGF 270% (0–1132%, p=0.46)]. (Table 1, Figure 1)

Comment

Placental development is dependent upon adequate invasion of the first trimester trophoblast into the maternal decidua in order to sufficiently remodel maternal spiral arteries.5 Conversely, incomplete invasion has been implicated in diverse adverse pregnancy outcomes, including fetal loss, fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia.4 We analyzed whether the embryo itself facilitates trophoblast invasion, and demonstrated that invasion of trophoblast cells is enhanced by exposure to sPIF. Our findings indicate that the embryo participates in controlling its own destiny, consistent with recent studies which demonstrate PIF’s immune modulatory role. The invasiveness of trophoblast described herein provides another novel feature of PIF’s action, which complements the trophic effect demonstrated in human decidual cells.10 In human decidual cells, PIF creates a favorable implantation milieu by modulating local immunity, promoting adhesion and controlling apoptosis. Together, these latter three elements are critical for implantation and form a compelling picture of PIF’s essential role. As PIF is secreted by the embryo, expressed in the placenta, and produced as early as the two-cell stage,8 it is rather plausible that PIF also influences placental development in the peri-implantation period.

In this in vitro study, sPIF effect was significant at physiologic concentrations. Additional studies are required to address extrapolation of these results to eventual application of PIF in vivo. The lack of effect with scrambled PIF further supports the possible biologic role of PIF in early pregnancy events.

Since EGF is a potent decidua-secreted growth factor, it was of interest to note that it too did not have a consistent effect on trophoblast invasion, when used at a physiologic concentration which is higher than the maximally effective sPIF dose (50nM) used. Additionally, EGF did not have a synergistic effect when added to this maximally effective sPIF dose. It is possible that PIF and EGF are competing for similar cell surface targets and/or intracellular pathways affecting trophoblast invasion. An additional consideration for these results may be that early cell passaging of the trophoblast cells affected the cell surface tyrosine kinase receptors for EGF on the trophoblast cell line, which would not have affected sPIF results as PIF is felt to exert its effect intracellularly.

Current understanding of interactions at the embryo-maternal interface incompletely explains the signaling which permits the maternal immune system to allow blastocyst implantation, trophoblast invasion and remodelling of maternal vessels.1,2 Multiple maternal immune cells are present, specific to the uterus (as differentiated by their unique cell surface markers), and are implicated in this process.3,7 Maternal macrophages and dendritic cells, through their antigen presenting, cytokine inducing and phagocytic properties,14 uterine natural killers cells through their apoptotic and likely vascular remodeling properties,3 and T regulatory cells through their cytokine modulation, all seem to play a likely role in decidual changes necessary for appropriate placental formation. The embryonic markers which trigger the activity of these cells are as yet incompletely identified. Preimplantation factor has previously been demonstrated to significantly affect immune response,10 and the presence of PIF at the site of the invading trophoblast may signal maternal acceptance of this invasion.

The autotrophic role of PIF on the embryo itself was recently demonstrated since addition of an anti-PIF-antibody into embryo culture media blocked significantly mouse blastocyst formation.15 Moreover, addition of sPIF led to increased survival of embryos cultured in in embryo toxic serum by directly binding to the blastocyst itself.16 Future examination of sPIF effect will include comparisons with other known stimulators of trophoblast invasion beyond EGF, to include Interleukin-6, Insulin-Like Growth Factor-2, urokinase-type plasminogen activator system, transforming growth factor-β, and hepatocyte growth factor.3,4 A pro-inflammatory milieu generated at the embryo-maternal interface includes the Interleukin-1 system (including IL-1β, and IL-18), as well as Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, Interleukin-11 and Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF). These molecules have been implicated in production of secondary mediators (chemokines, matrix metalloproteinases, and prostaglandins), expression of adhesion molecules and endometrial remodeling. The role of PIF in this milieu is not entirely clear and warrants further evaluation.

The limitations of this study include its in vitro design, which underestimates the complicated interaction of the multiple factors involved in this process in vivo. The use of an immortalized cell line also may not precisely represent the in vivo response of first trimester trophoblast cells, and may also have exhibited a passage effect on results. An additional weakness of the study is that the person assessing cell invasion was not blinded to the treatment of the well.

The strengths of the study are: 1) we used a well established in vitro system to investigate trophoblast invasion; 2) we employed synthetic PIF, whose structure is identical to native PIF, and in concentrations similar to maternal circulating levels; 3) we compared the effects of sPIF to EGF, a well recognized factor that promotes trophoblast invasion.

In conclusion, sPIF, at low concentrations that mimick levels present in the circulation of pregnant women, promotes trophoblast invasion. The interaction between PIF and other known regulators of trophoblast development, and key maternal immune cells such as dendritic cells, macrophages and uterine natural killer cells, warrants further investigation. The present findings, coupled with the known decidual cell effects of sPIF, strongly suggest that this peptide should be investigated to prevent or treat pregnancy complications involving defective placentation as a distinguishing feature.

Acknowledgments

Research conducted at Yale University, New Haven, CT, supported by BioIncept, LLC (MJP) and NIH grant 5R01HD056123-02 (SJH)

Footnotes

Poster presentation, Abstract 211 at the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine 30th Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, February 4, 2010

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Than NG, Paidas MJ, Mizutani S, Sharma S, Padbury J, Barnea ER. Embryo-placento-maternal interaction and biomarkers: From diagnosis to therapy--a workshop report. Placenta. 2007 Apr;28(Suppl A):S107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Rango U. Fetal tolerance in human pregnancy--a crucial balance between acceptance and limitation of trophoblast invasion. Immunol Lett. 2008 Jan 15;115(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salamonsen LA, Hannan NJ, Dimitriadis E. Cytokines and chemokines during human embryo implantation: Roles in implantation and early placentation. Semin Reprod Med. 2007 Nov;25(6):437–44. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lala PK, Chakraborty C. Factors regulating trophoblast migration and invasiveness: Possible derangements contributing to pre-eclampsia and fetal injury. Placenta. 2003 Jul;24(6):575–87. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(03)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orsi NM, Tribe RM. Cytokine networks and the regulation of uterine function in pregnancy and parturition. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008 Apr;20(4):462–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jovanovic M, Vicovac L. Interleukin-6 stimulates cell migration, invasion and integrin expression in HTR-8/SVneo cell line. Placenta. 2009 Apr;30(4):320–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garlanda C, Maina V, Martinez de la Torre Y, Nebuloni M, Locati M. Inflammatory reaction and implantation: The new entries PTX3 and D6. Placenta. 2008 Oct;29( Suppl B):129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roussev RG, Coulam CB, Barnea ER. Development and validation of an assay for measuring preimplantation factor (PIF) of embryonal origin. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 1996 Mar;35(3):281–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnea ER, Simon J, Levine SP, Coulam CB, Taliadouros GS, Leavis PC. Progress in characterization of pre-implantation factor in embryo cultures and in vivo. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 1999 Aug;42(2):95–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paidas MJ, Krikun G, Huang SJ, Jones R, Romano M, Annunziato J, Barnea ER. Genomic and Proteomic Investigation of Preimplantation Factor’s Impact on Human Decidual Cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.024. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaMarca HL, Dash PR, Vishnuthevan K, Harvey E, Sullivan DE, Morris CA, Whitley GSJ. Epidermal growth factor-stimulated extravillous cytotrophoblast motility is mediated by the activation of PI3-K, Akt and both p38 and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Human Reproduction. 2008 May;23(8):1733–1741. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staun-Ram E, Shalev E. Human trophoblast function during the implantation process. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2005 Oct;3:56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aldo PB, Krikun G, Visintin I, Lockwood C, Romero R, Mor G. A novel three-dimensional in vitro system to study trophoblast-endothelium cell interactions. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007 Aug;58(2):98–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang SJ, Chen CP, Schatz F, Rahman M, Abrahams VM, Lockwood CJ. Pre-eclampsia is associated with dendritic cell recruitment into the uterine decidua. J Pathol. 2008 Feb;214(3):328–36. doi: 10.1002/path.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamatkin CW, Roussev RG, Ramu S, Coulam CB, Barnea ER. Endogenous PIF is essential for embryo development: Anti-PIF mAb impairs embryonic development in vitro. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2009;61:419. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stamatkin CW, Roussev RG, Ramu S, Coulam CB, Barnea ER. Preimplantation factor (PIF) binds to specific embryo sites to act as a rescue factor for embryo demise due to embryo toxic serum. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2009;61:418. [Google Scholar]