Abstract

Background

Metastatic disease commonly affects the proximal femur and occasionally the acetabulum. Surgical options include the use of a protrusio cage with a THA. However, the complications and survivorship of these cages for this indication is unknown.

Questions/purposes

The purpose was to report the restoration of function, complications and implant survival.

Methods

The medical records of 29 patients undergoing insertion of a protrusio cage for metastatic pelvic disease were reviewed. Complications were recorded. The most common diagnosis was metastatic breast cancer. During the review process, all but 10 of the 29 patients died 1–73 months after surgery. The median length of survival was 12 months (range, 3 days–100 months) after the procedure; 11 patients were alive at last followup at a median of 16 months (range, 1–100 months).

Results

One patient had loss of fixation owing to disease progression. Five patients had dislocations, four of which were treated. There were three deep infections (two that led to dislocation, which proceeded to revision surgery). Ten patients of the 29 patients became household ambulators, 17 became community ambulators, two remained chair-bound, and one bed-bound.

Conclusions

The protrusio cage allowed most patients to return to walking with only one mechanical failure.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Metastatic bone disease commonly affects the proximal femur [2]. Hip arthroplasty has been advocated as an effective treatment for this [4, 6, 8, 12]. Metastases involving the acetabulum are less common and treatment has been more controversial [5]. Harrington [4] described using a protrusio ring, with or without augmentation, for Class II and III acetabular disease. Following this recommendation, he reported one further study reported on this procedure [5]. Harrington [4] reported, in his series of 58 patients, 40 were ambulant preoperatively and 18 were nonambulant. Postoperatively, 54 became ambulant while four remained nonambulant. Complications reported included a superficial wound infection in two, a nonfatal pulmonary embolus in one, one complete iatrogenic femoral nerve palsy, and one perioperative death due to massive intraoperative blood loss. The mean length of survival was 19 months. Loosening of the acetabular cup developed in five patients, all due to progression of disease. There were no reports of femoral loosening.

Protrusio cages have also been used for pelvic discontinuity secondary to failed total joint arthroplasty [3, 9–11]. Paprosky et al. [9] reported a 31% revision rate for loosening after inserting 16 cages. Complications not due to loosening occurred in a further 38%. These included an infection, which proceeded to resection arthroplasty, a dislocation, and four sciatic nerve injuries. Peters et al. [11] reported an overall complication rate of 30%. Of these, 24% were major (which included a revision rate of 13%) and 6% were minor complications.

This study is essentially a Phase 1 trial of a new implant intended for metastatic cancer involving the acetabulum. The implant eliminates the need for a second procedure to insert pins and/or threaded screws. It also eliminates the need to curette the tumor as the prosthesis can be placed so that it spans medial wall defects and provides fixation across pelvic discontinuity. It provides a stable base to cement a cup in any orientation.

The purpose of this report is to describe (1) the failure rate of this new device; (2) the complication rate; and (3) the survival of patients with metastatic disease involving the acetabulum treated with this device.

Patients and Methods

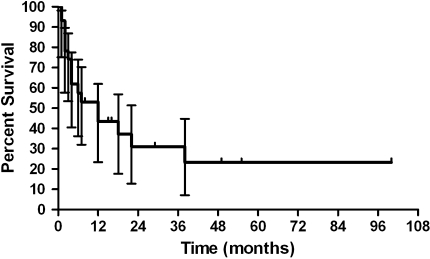

Twenty-nine patients (29 hips) who had DePuy protrusio cages (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc, Warsaw, IN) for metastatic disease of the acetabulum between 1999 and 2009 were reviewed (Fig. 1). There were 12 men and 17 women with a mean age of 67 years (range, 30–82 years). The indication for its use was metastatic disease involving the acetabulum resulting in either acute fracture of the acetabulum producing protrusio or impending fracture (Harrington Class II in13 patients and Class III in 16 [4, 7]) and they were an acceptable anesthetic risk and they had not had radiation treatment to the surgical site in the last six weeks; in two patients, the cage was inserted to revise a failed hip hemiarthroplasty or THA because of disease progression producing acetabular collapse. The surgical approach was posterolateral in 26, direct lateral (transtrochanteric) in two and Kocher-Langenbeck in one (in association with a type 2-3 resection). The median surgical time was 131 minutes (range 95–295 minutes). The most common underlying malignancy was breast cancer (Table 1). Twenty-two patients presented with metastatic disease affecting bone and viscera and seven with bone metastases only. Followup until death was undertaken by the author at serial intervals. During the review period, 18 of the 29 patients died. The median length of survival was 12 months (range, 3 days–100 months) after the procedure; 11 patients were alive at last followup at a median of 16 months (range, 1–100 months) (Fig. 2). No patient has been lost to review and all patient records were reviewed prospectively. All, with one exception, received radiation treatment to the affected hip, 15 before surgery and 13 after surgery. Eleven patients received chemotherapy before their surgical procedure.

Fig. 1A–B.

(A) The DePuy protrusio cage is shown in this photograph. (B) A plain radiograph demonstrating a cage in situ is shown.

Table 1.

Demographics and prostheses used

| Age(years) | Gender | Primary pathology | Side | Approach | Cage size | Acetabular prosthesis | Cup size | Femoral prosthesis | Had sized | Neck length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 71 | Male | Colon | Right | P | 58 | Eska 10˚ hood | 49 | Eska | 28 | 0 |

| 66 | Female | Myeloma | Right | P | 58 | Charnley LPW | 44 | Charnley | 22 | |

| 82 | Male | Bladder | Left | P | 56 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 55 | Female | Breast | Right | P | 52 | Charnley elite plus LPW | 40 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 74 | Male | Colon | Right | P | 52 | Eska 10˚ hood | 46 | Eska | 28 | 0 |

| 81 | Male | Renal | Right | TT | 56 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 49 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 75 | Female | Breast | Left | P | 52 | ZCA neutral | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 30 | Female | Breast | Right | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | −3.5 |

| 78 | Female | Merkel cell | Left | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 79 | Male | Prostate | Right | P | 52 | Charnley LPW | 43 | Charnley | 22 | |

| 54 | Female | Breast | Right | P | 52 | Eska 10˚ hood | 46 | Eska | 28 | −3.5 |

| 66 | Female | Breast | Right | P | 52 | Charnley LPW | 40 | Charnley | 22 | |

| 77 | Female | Renal | Left | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 56 | Female | Lung SCC | Right | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 55 | Male | NHL | Left | P | 56 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 49 | Versys | 32 | 0 |

| 76 | Female | Colon | Right | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 77 | Female | Breast | Left | P | 52 | Charnley LPW | 43 | Charnley | 22 | |

| 56 | Female | Uterine* | Left | K-L | 56 | Eska 10˚ hood | 47 | Eska | 28 | 0 |

| 58 | Male | Lung SCC* | Right | P | 56 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 51 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 75 | Male | Prostate | Left | P | 56 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | −3.5 |

| 82 | Female | Esophageal* | Left | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 58 | Male | Bladder | Right | TT | 60 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 53 | Male | Rectal | Left | P | 56 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 49 | Versys | 32 | 0 |

| 76 | Male | Myeloma | Left | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

| 61 | Female | Myeloma, failed hemiarthroplasty | Right | P | 48 | Eska 10˚ hood | 44 | Eska | 28 | −3.5 |

| 69 | Female | Melanoma | Left | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 45 | Versys | 22 | −2 |

| 67 | Female | NHL* | Left | P | 52 | Charnley LPW | 43 | Charnley | 22 | |

| 56 | Female | Lung, failed THA* | Right | P | 52 | ZCA 10˚ hood | 47 | Versys | 28 | 0 |

* Indicates those cases that dislocated; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; NHL = Non Hodgkin’s lymphoma; P = posterior approach; TT = transtrochanteric approach; K-L = Kocher-Langenbeck approach; LPW = long posterior wall.

Fig. 2.

A graph shows the survival of all patients, with 95% confidence intervals at time points after the procedure. Median life expectancy in this group is 12 months.

A variety of femoral stems and acetabular cups were used as implants changed during the years (Table 1). Initially the 15-inch Charnley monobloc femoral stem (Thackray, Leeds, UK) was used; this was replaced in 2003 by the Versys CRC 300-mm modular femoral stem (Zimmer, Inc, Warsaw, IN) and was replaced by the Eska 350-mm modular femoral stem (Eska, Lubeck, Germany) in 2009. All are cemented implants. The acetabular cups were the Charnley LPW for Charnley stems, the ZCA for Zimmer stems, and the Eska for Eska stems. The head size was 22 mm for Charnley stems, 28 mm for Zimmer stems (with two exceptions a 32-mm head), and 28 mm for Eska stems. All cups, with one exception, were hooded (Table 1).

The THAs were implanted through a posterolateral approach in 26 cases, a transtrochanteric in two, and a Kocher-Langenbeck approach in one. There was no additional fixation with Steinmann pins. It was noted the cage did not always fit the anatomy, particularly in women (ischial fixation was not possible in eight of 17 women compared to one of 12 men). The placement of the ischial limb of the prosthesis was relatively vertical to the ilium (the angle between the ilial limb and the ischial limb of the prosthesis is 125°). Commonly the female ischial tuberosity extends from the inferior aspect of the acetabulum at a sharper angle than the male, which meant the ischial limb of the prosthesis could only engage the ischial ramus if it was rotated; thus, the iliac limb did not fully engage the ilium over the acetabulum. In this situation, the cage was seated relative to the ilium and screw fixation was limited to the ilium only. The only cage to lose fixation had fixation to the ilium alone. Simplex® with tobramycin cement (Howmedica International, Limerick, Ireland) was used for all cases and the cement was applied by syringe into the cage and behind the cage’s medial wall. The liner was positioned in 40° to 55° of horizontal inclination.

Patients were allowed to stand with full weightbearing on the first postoperative day under the supervision of a physiotherapist. Mobilization was commenced from the first postoperative day, but sitting in a high chair was not allowed until the fourth postoperative day on the initial patients but this was reduced to the third postoperative day in 2008. Walking aids initially consisted of a walker and progression to a cane as comfort allowed. In some patients, the walking cane was also discarded. All patients received radiation treatment either before (14 patients) or after surgery.

Clinical reviews were conducted at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and yearly after surgery but this review program was modified in keeping with the patients’ condition. Patients were asked to self-report their level of pain compared to preoperatively. Plain radiographs were taken at the 6 week and yearly review or at any time symptoms indicated the need for repeat imaging. At each review patients were assessed for clinical and radiographic complications (including subsidence, loosening, screw breakage, plate fracture) that might not produce symptoms. Ambulatory status was recorded at each review. An attempt at functional evaluation was also initiated early in the project but was abandoned as patient function was too dependent on the underlying disease state and not the surgical procedure: presentations varied from an initial presentation of a chronic condition such as a plasmacytoma to end-stage terminal with disseminated disease. Thirteen patients presented either chair- or bed-bound due to an acute pathologic fracture.

Survival data were analyzed with a Kaplan-Meier survival curve using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Ten patients became household ambulators, 17 became community ambulators, two remained chair bound, and one bed bound (died 5 days after surgery due to a brain stem infarct 12 hours after surgery). One patient did not respond to local and systemic treatment and succumbed to disease 3 weeks after surgery after loss of fixation and avulsion of the cage (at two weeks postoperative) due to disease progression despite fixation with five screws into the ilium. In the remainder, ambulatory status deteriorated in direct proportion to systemic disease progression. Twenty one patients reported a decrease in hip pain at the six week review compared to preoperatively, three reported it unchanged, in three it was not recorded and two died prior to the six week review.

Complications developed in nine patients, all within the perioperative period. Surgical complications accounted for six of these (five major, one minor). The most common was dislocation, which occurred in five. Dislocation developed after deep infection in two, avulsion of the cage due to progressive bone loss in one, and generalized poor muscle tone due to cachexia in two patients who were in the last days of their lives. The dislocations were treated by an open reduction and revision of the liner in one, open reduction only in another, closed reduction in one, and no treatment for two because they were unfit for surgery due to impending death. There were three infections, all deep, one a recurrence of a preexisting infection. There was one revision procedure, which was to remove all metal work for persistent infection and recurrent dislocation. There was only one cage that lost fixation (see above).

During the review period, 18 of the 29 patients died. The median length of survival was 12 months (range, 3 days–100 months) after the procedure; 11 patients were alive at last followup at a median of 16 months (range, 1–100 months).

Discussion

THA for metastatic disease has been previously described and is well accepted as a treatment modality [1, 4, 5, 12–14]. Metastases involving the acetabulum are a problem for which treatment options and outcomes have rarely been reported [1, 4, 5, 8]. A new implant that provides a greater surface area for fixation is commercially available. It does not require the use of supplemental fixation with Steinmann pins. The purpose of this study was to determine (1) the failure rate; (2) the complication rate; and (3) the patient survivorship with this new device.

There were several limitations to this study. First, there were a relatively small number of patients. The indications for this device are uncommon; these patients were operated over a period of ten years, and it would be difficult to obtain a large series. Nonetheless, the series demonstrate the utility of the device. Second, we did not use a contemporary, validated outcome instrument to assess function. Most of these patients will not survive long periods and it is therefore most important to restore simple rather than high levels of functions.

The DePuy cage was inserted without supplemental Steinmann pins. Only one failed due to loss of fixation, which was secondary to local disease progression. Another failed due to intractable infection. The length of review has extended out to 100 months in one patient and fixation remains intact. The failure rate is therefore quite low.

Several authors have been published on the use of acetabular (protrusio and antiprotrusio) rings. Harrington [4] reported on the treatment of acetabular insufficiency secondary to metastatic disease in a series of 48 patients. A Harris-Oh protrusio acetabular shell in addition to mesh along the medial wall was used for 25 patients and this shell, with the addition of threaded Steinmann pins into the ilium, was used for another 19 patients. This acetabular shell had a small superior lip with which to buttress against the superior acetabulum. Three acetabular prostheses loosened due to disease progression. Papagelopoulos et al. [8] reported 53 THAs in patients with myeloma of which 13 had reconstruction of the acetabulum with a protrusio ring and methylmethacrylate with or without threaded Steinmann pins. They reported only two revisions (one for recurrent dislocation and one for infection) among the 53 patients with followup ranging from 7 days to 19.9 years.

Complications developed in nine patients of which five were dislocations. Schneiderbauer et al. [12] reported on the dislocation rate for 320 hemiarthroplasties for tumor-related conditions of the femoral neck. Of these, 195 were for metastatic bone cancer. They reported a dislocation rate of 10.9% but did not report on any other complications. Marco et al. [7] reported on 54 patients with metastatic disease of the acetabulum treated by total hip replacement and either acetabular augmentation with pins and cement and a flanged acetabular shell (51) or a flanged acetabular shell alone (3). They report only one case of subluxation and a complication rate of 22% including failure of fixation in 9%. The dislocation rate in the current study is quite high but is comparable to the dislocation rate for protrusio cages after nonneoplastic revision surgery, and, in addition, in this study, 50% of the dislocations were due to end-stage problems of muscle tone in the presence of cancer cachexia. A capture-style cup may be an appropriate addition to this procedure if this problem is anticipated.

The median length of survival was 12 months (range, 3 days–100 months) after the procedure with two deaths in the perioperative period. There were no intraoperative deaths. Harrington [4] reported there were two intraoperative deaths in his series and a mean length of survival of 19 months. Marco et al. [7] reported a median survival of three months in those with bone and visceral metastases and 12 months with bone metastases only. The survival rate of the patients in the current study is therefore consistent with that previously published and therefore this implant did not appear to have any adverse effect on patient survival.

These observations suggest this option is reasonable for acetabular disease and can provide stable fixation without the need for additional fixation. Consideration of expanding the range of cages with a cage with a sharper angle to the ischial wing should be considered.

Footnotes

The author certifies that he has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Allan DG, Bell RS, Davis A, Langer F. Complex acetabular reconstruction for metastatic tumor. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:301–306. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(05)80178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman R. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer. 1997;80(8 Suppl):1588–1594. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1588::AID-CNCR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill TJ, Sledge JB, Müller ME. The Bürch-Schneider anti-protrusio cage in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:946–953. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B6.8658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrington KD. The management of acetabular insufficiency secondary to metastatic malignant disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:653–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrington KD. Orthopedic surgical management of skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer. 1997;80(8 Suppl):1614–1627. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1614::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrenbruck T, Erickson EW, Damron TA, Heiner J. Adverse clinical events during cemented long-stem femoral arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;395:154–163. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200202000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marco R, Sheth DS, Boland PJ, Wunder JS, Siegel JA, Healey J. Functional and oncological outcome of acetabular reconstruction in the treatment of metastatic disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:642–651. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200005000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papagelopoulos PJ, Galanis EC, Greipp PR, Sim FH. Prosthetic hip replacement for pathologic or impending pathologic fractures in myeloma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;341:192–205. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199708000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paprosky W, Sporer S, O’Rourke MR. The treatment of pelvic discontinuity with acetabular cages. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:183–187. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000246530.52253.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perka C, Ludwig R. Reconstruction of segmental defects during revision procedures of the acetabulum with the Burch-Schneider anti-protrusio cage. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:568–574. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.23919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters CL, Miller M, Erickson J, Hall P, Samuelson K. Acetabular revision with a modular anti-protrusio acetabular component. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(7 Suppl 2):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneiderbauer MM, Sierra RJ, Schleck C, Harmsen WS, Scully SP. Dislocation rate after hip hemiarthroplasty in patients with tumor-related conditions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1810–1815. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker R. Pelvic reconstruction/total hip arthroplasty for metastatic acetabular insufficiency. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;294:170–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yazawa Y, Frassica FJ, Chao EY, Pritchard DJ, Sim FH, Shives TC. Metastatic bone disease: a study of the surgical treatment of 166 pathologic humeral and femoral fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;251:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]