Abstract

Hormonally active vitamin D3, 1,25-(OH)2D3, is believed to have a role in the prevention of cancer formation and in limiting the aggressiveness of cancers that do arise. Therefore, much interest is presently being focused on 1,25-(OH)2D3 and its analogues as potential treatments for various cancers including melanoma. This article discusses the evidence in favour of a role for 1,25-(OH)2D3 in protection against the progression of melanocytic lesions and also summarizes the mechanisms by which 1,25-(OH)2D3 may act to protect against melanoma development and progression.

Keywords: cancer, melanocytic, melanoma, nevi, vitamin D

Introduction

Melanoma arises in activated and genetically altered melanocytes following a complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors. Cutaneous melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer, causing 72% of skin cancer deaths (1). This high mortality rate has occurred as a result of the poor efficacy of established chemotherapeutic medications. While there have recently been a number of promising advances in melanoma treatment research (2), there remains a pressing need for the development of preventative and improved therapeutic treatments. One option being considered is the principal hormonally active form of vitamin D, 1,25-(OH)2D3, and its analogues.

1,25-(OH)2D3 has an important role in calcium homeostasis and is also believed to protect against cancer development (3–6). This anti-neoplastic activity results from the ability of 1,25-(OH)2D3 to regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and apoptosis. Vitamin D receptors (VDRs) are widely expressed (6,7), including in the skin where they occur in melanocytes (8) and most other cells. Therefore, the anti-neoplastic activity of 1,25-(OH)2D3 may affect a wide variety of cells including melanocytes. This article will focus on the evidence that vitamin D, and particularly 1,25-(OH)2D3, has a role in preventing the progression of melanocytic neoplasms and will examine mechanisms by which 1,25-(OH)2D3 may exert its effects.

Vitamin D synthesis

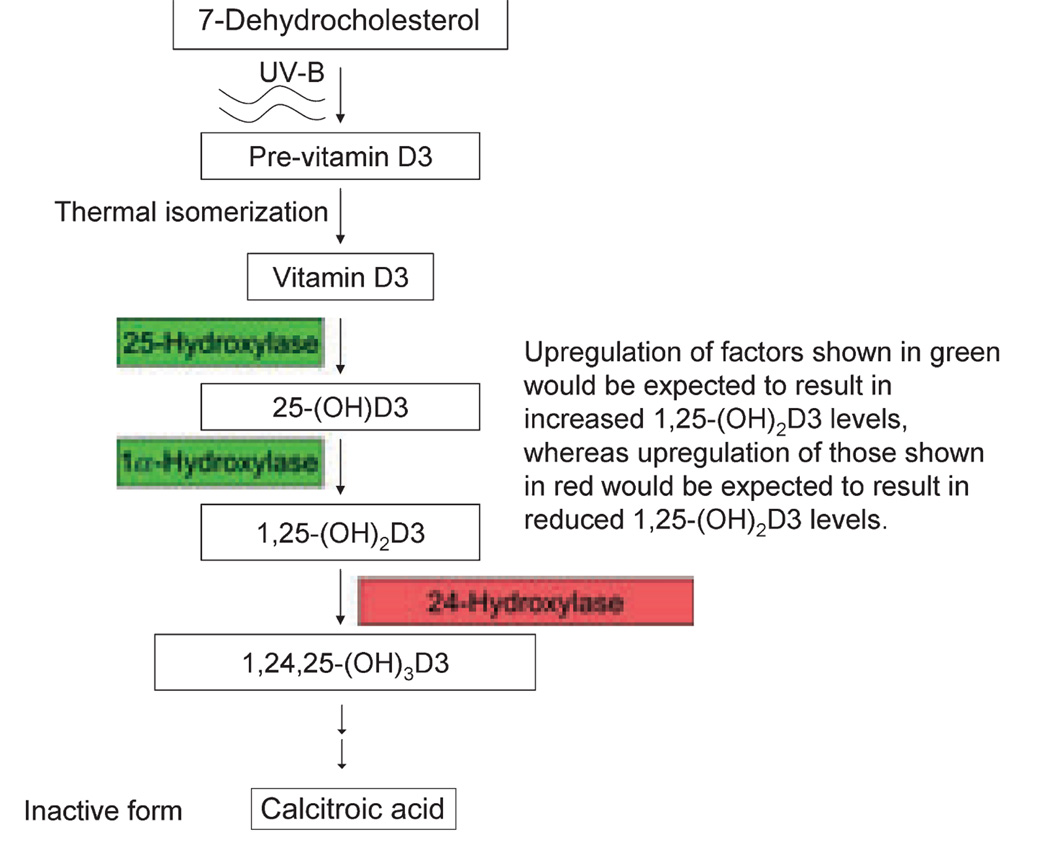

Between 90% and 100% of vitamin D is obtained through biosynthesis following exposure to ultraviolet-B radiation (UV-B) (9). Synthesis begins in keratinocytes through UV-B-mediated photolysis of 7-dehydrocholesterol, forming previtamin D3, with subsequent thermal isomerization to vitamin D3 (Fig. 1) (6,10). This is then converted to 25-(OH)D3 by the enzyme 25-hydroxylase (CYP27A1), with subsequent conversion to 1,25-(OH)2D3 by 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1). These later two reactions occur in the liver and kidneys, respectively. In addition, both enzymes are expressed in keratinocytes (11), and 1α-hydroxylase is expressed in many cells (12) including some melanomas (13).

Figure 1.

The pathway of 1,25-(OH)2D3 synthesis begins in the skin with UV-B-induced previtamin D3 production and ends with the production of the inactive end product calcitroic acid. The figure demonstrates how changes in synthetic (green) and degradative enzymes (red) might affect 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels.

Metabolism of 1,25-(OH)2D3 is mediated principally by the multi-catalytic enzyme 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1). 24-Hydroxylase induction occurs in response to 1,25-(OH)2D3, and its cellular expression therefore mirrors that of the VDR (14).

UV exposure as a risk factor for melanoma

Sun exposure is widely accepted as a risk factor for all forms of skin cancer including melanoma (15). However, epidemiological evidence suggests that melanoma differs from other skin cancers because its development relates more to timing and severity of UV exposure than to cumulative amounts (lentigo maligna being an exception) (16). Therefore, fair-skinned people who experience occasional and intense UV exposure resulting in severe sunburn, particularly as young children, are far more likely to develop melanoma than those who are chronically exposed or exposed at an older age (17,18). Studies in transgenic mice support this view and show that early severe UV exposure results in an increased risk of melanoma-like malignancies, whereas later exposure does not (19). Further support is provided by geographical studies showing a non-linear relationship between latitude (reflecting UV exposure) and melanoma (18). Furthermore, cumulative UV exposure (assessed by solar elastosis) correlates in some studies with later onset (20) and decreased severity of melanoma (21). However, this later study (21) has proved controversial (22–25). Other researchers have not identified any protective effect from cumulative UV exposure (assessed using patient history) (25). One group (24) has suggested that the apparent decreased melanoma severity associated with cumulative UV exposure may actually reflect differing pathways of melanoma formation, with less aggressive forms developing through UV-induced mutations and more aggressive familial forms developing through endogenous instability in susceptible individuals. Actually, familial and sporadic forms of melanoma are similarly aggressive and share common mutations at CDKN2a and CDK4 (26,27). However, genetic analyses do suggest that divergent pathways of melanoma development occur at different body sites (28,29). For example, melanomas arising in intermittently sun-exposed skin more commonly harbour mutations in BRAF and NRAS, while mutations in c-KIT are more common in chronically sun-exposed skin (29). These differences may account for some of the non-linearity seen in geographical studies. Nevertheless, the studies described (17,18,20,21) do suggest that chronic UV exposure may provide some protection against melanoma, with one likely causal factor being 1,25-(OH)2D3 production.

VDR gene polymorphism studies

Numerous VDR gene polymorphism epidemiological studies have been undertaken examining the relationship between 1,25-(OH)2D3 and melanoma risk. Because of inconsistencies in the findings from smaller studies, two large meta-analyses were recently performed (30,31). Individually, these meta-analyses identified RFLPs that were associated with either increased or reduced risk of melanoma. However, collectively the findings from these studies are contradictory and thus difficult to interpret. The variability in the results from these studies may relate to factors that include sample size and differences in the effect of VDR SNPs on VDR expression in different people; however, this remains to be determined.

The role of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in melanin synthesis

The importance of melanin pigment in protection against melanoma is highlighted by differences in lifetime melanoma risk in fair-skinned Americans (1 in 50) versus African Americans (1 in 1000) (32). Furthermore, when melanoma arises in African Americans, it mainly involves sites of reduced pigmentation such as mucosal surfaces and acral areas (32).

Melanocytes act as master regulators of the skin, sensing injury and maintaining homeostasis (33). One of their homeostatic mechanisms is the synthesis of melanin pigment. During sun exposure, the skin is bombarded with UV radiation that damages cells through genetic mutations. Mutagenic effects are caused principally by UV-B and to a lesser extent by UV-A (34). UV-induced epidermal stress in melanocytes and keratinocytes triggers the synthesis of proopiomelanocortin (POMC), which is subsequently converted to ACTH (35). ACTH, acting in concert with α-MSH (also derived from POMC), binds to the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) on melanocytes which causes an increase in intracytoplasmic cAMP (33). This results in upregulation of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) transcription. MITF then binds to the promoter of tyrosinase causing upregulation (36) and increased melanin synthesis.

Vitamin D is also believed to upregulate melanin synthesis (33,37), with evidence coming from both in vitro (38–42) and in vivo (43) studies. With the exception of a single study (39), in which high variability made interpretation difficult, all the in vitro studies described increases in tyrosinase activity in response to either vitamin D3 or 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment. An in vivo study (43) similarly showed increased tyrosinase activity following UV exposure in rats fed diets rich in vitamin D compared with vitamin D-deficient rats.

1,25-(OH)2D3 is believed to upregulate melanin synthesis through increased c-kit activity. In one study, the use of the 1,25-(OH)2D3 analogue, tacalcitol, caused an up-regulation of c-kit (44), and in others 1,25-(OH)2D3 caused increased Raf and mitogen-activated protein (MAP)-kinase activity (45,46). c-Kit acts through the Ras-Raf pathway to activate MAP-kinase, which has a minor role in upregulating MITF expression and a more important role in the phosphorylation of MITF causing an increase in its activity and its degradation (47,48).

The Ras-Raf pathway is a common site of mutation in melanoma and is thus considered to have a critical role in melanoma development. However, minor stimulation to this pathway from individual growth factors (stem-cell factor, fibroblast growth factor, etc.), acting independently, is not considered significant in melanoma formation (27). This is also likely to be true for the stimulation to this pathway from 1,25-(OH)2D3.

The role of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in protection against UV-induced melanocytic neoplasms

In addition to melanin synthesis, other important factors in skin protection from UV include endogenous DNA repair systems and possibly 1,25-(OH)2D3. UV exposure causes nevus formation through a poorly understood mechanism. Factors likely to be involved include proliferative responses induced in melanocytes by UV damage and UV-induced genetic mutations (49,50). Proliferation following UV exposure occurs because of the effects of α-MSH, endothelin1 and keratinocyte-derived basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (33,51–53). In addition, proliferation occurs owing to mutations in key regions of growth and cell death regulatory genes (27). More specifically, there is evidence that upregulation of the anti-apoptotic factor survivin (54) is important in nevus formation. Mutations in B-RAF (55) are also commonly identified in nevi; however, it is unclear whether these are causative or simply a late development (56). Nevertheless, the frequent identification of identical B-RAF mutations in nevi and melanomas (V600E) has led to the suggestion that these mutations may represent an important step along the pathway to melanoma development (57).

While generally benign behaving, melanocytic nevi are a recognized risk factor for melanoma when present in increased numbers. In addition, melanocytic nevi are often found associated with melanoma and may act as melanoma precursor lesions (53,58,59). 1,25-(OH)2D3 regulates survivin levels in breast (60) and colon cancer cells (61) and improves the barrier function of the skin following suberythemal doses of UV-B (62). Through these mechanisms as well as its anti-proliferative and anti-mutagenic (63,64) activities, 1,25-(OH)2D3 may have a role in reducing the incidence of melanocytic nevi and in decreasing their rate of progression to melanoma.

Dysplastic nevi are far more widely accepted as melanoma precursor lesions (65) than melanocytic nevi and are also associated with increased survivin levels (54). Through all of the same mechanisms described for melanocytic nevi, 1,25-(OH)2D3 may also help to protect against the development and progression of other melanocytic nevi, such as dysplastic nevi.

The role of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in protection against melanoma

1,25-(OH)2D3 may also have an important role in protection against melanoma (see Figure S1). VDRs act as both intranuclear and intracytoplasmic receptors. Within the nucleus, the VDR forms a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) and then binds to the promoter of target genes containing appropriate 1,25-(OH)2D3 responsive elements (VDREs), which modulates their expression (66).

The anti-proliferative effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 against melanoma and other neoplasms are believed to centre on its ability to inhibit proliferation through the G1/S checkpoint of the cell cycle. Tumor suppressor genes controlling progression through G1/S are among the most frequently inactivated genes in melanoma (27,67), and mutations in 9p21 (coding for the G1/S inhibitors p14 and p16) are believed to play an important role in early melanoma development from nevi (59). 1,25-(OH)2D3 inhibits proliferation through G1/S by upregulating the p21 and p27 cell cycle inhibitors and by inhibiting cyclin D1 [reviewed in (66)].

In addition, some of the anti-neoplastic effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 result from modulation of the activity of growth factors. For example, 1,25-(OH)2D3 downregulates the activity of growth factors including EGFR (68). Unregulated EGFR autocrine signalling is a feature associated with progression in melanoma (69). 1,25-(OH)2D3 upregulates the activity of growth factors including TGF-β (70). TGF-β signalling shares many of the characteristic anti-neoplastic features associated with 1,25-(OH)2D3 including inhibition of cell proliferation and promotion of cell differentiation and apoptosis.

1,25-(OH)2D3 also increases apoptosis in melanoma (71) through various mechanisms. One of these is through downregulation of the anti-apoptotic factor survivin (60), already discussed in regard to nevi development. Survivin is strongly expressed in malignant melanoma (72,73), and inhibitors of survivin cause melanoma regression (72,74,75). A second mechanism occurs through a vitamin D-induced increase in intra-cytoplasmic calcium leading to activation of Calpain (calcium-activated neutral protease) (76). The pro-apoptotic effects of Calpain are mediated through proteolysis and include cleavage of Bax. The Bax cleavage product is a potent inducer of apoptosis. A further pro-apoptotic mechanism suggested for 1,25-(OH)2D3 is decreased expression of the secretory form of clusterin (77). In its secretory form, the clusterin glycoprotein has anti-apoptotic activity, and this molecule is expressed in a minority of melanoma cases, particularly those of the primary desmoplastic variety (78). Further discussion of 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated anti-neoplastic pathways in melanoma can be found in Osborne and Hutchinson (66).

1,25-(OH)2D3 acting via c-Kit causes stimulation to the MAP-kinase pathway and ultimately increases MITF activity. Mutations stimulating this pathway occur commonly in melanoma, potentially raising concerns regarding the safety of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in melanoma prevention/treatment. As we stated earlier, we doubt that stimulation from 1,25-(OH)2D3 will prove physiologically significant. However, before highly potent 1,25-(OH)2D3 analogues gain widespread therapeutic use, the effect of this stimulation will certainly need to be evaluated.

In vitro (cell culture) studies

In vitro studies have been performed by several groups examining the effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on melanocyte proliferation (71,79,80). In studies using melanoma cell lines, Seifert et al. (80) showed that some cell lines do not express VDRs and are therefore resistant to 1,25-(OH)2D3. By contrast, the same group showed that in melanoma cell lines expressing the VDR, 1,25-(OH)2D3 had a dramatic ability to inhibit proliferation. Inhibition of proliferation was also seen in the studies of Colston et al. (79) and Danielsson et al. (71) both involving melanoma cell lines. Reichrath et al. (81) examined the effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on seven melanoma cell lines and found that only three were responsive. They therefore suggested that if these findings are more widely representative of melanoma behaviour in vivo, then it would suggest that 1,25-(OH)2D3 and its analogues may have limited efficacy in treating advanced stages of melanoma.

In vivo studies

The importance of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in the prevention of skin malignancy is perhaps best demonstrated by in vivo studies performed in VDR knockout mice (82,83). Zinser et al. (82) showed that mice lacking a VDR are prone to develop cutaneous malignancies following oral administration of carcinogens. The lesions mainly (80%) consisted of sebaceous, squamous or follicular papillomas, with less frequent development of melanotic foci (mice do not develop melanomas per se) and other lesions. The importance of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in limiting malignant disease progression is also highlighted by the in vivo studies of Chung et al. (84) which showed that prostate tumors transplanted into VDR-knockout mice grew larger than those growing in wild-type mice. The authors attributed this effect, at least in part, to the inhibitory effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on endothelial cell proliferation (84).

Effects of 25-(OH)D3 levels and melanoma

The data regarding the effect of 25-(OH)D3 levels on melanoma are supportive. Nurnberg et al. (85) showed that reduced 25-(OH)D3 levels correlate with increased stage of melanoma. Similarly, Newton-Bishop et al. (86) showed that higher 25-(OH)D3 levels are associated with both thinner tumors and better survival from melanoma. It is important to note that the flaw in these studies is that they examined 25-(OH)D3 levels at discrete time points, whereas 25-(OH)D3 levels constantly fluctuate owing to seasonal as well as lifestyle factors.

Effects of CYP24A1 over-expression

Changes in the levels of synthetic or degradative factors involved in 1,25-(OH)2D3 production would be expected to change 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels, and as a consequence anti-neoplastic activity (Fig. 1). However, very few studies have examined this question in regard to melanoma. One component of the pathway that has been studied is the degradative enzyme CYP24A1. CYP24A1 amplification has been described in breast and lung cancer (87,88). An upregulation in the entire long arm of chromosome 20 (containing CYP24A1) is known to occur in melanoma (89). However, upregulation of CYP24A1 is not believed to have a significant role in the pathogenesis of melanoma (89,90).

Clinical implications

Evidence in favour of a role for 1,25-(OH)2D3 in the prevention of melanoma is extensive and includes epidemiological, in vitro and in vivo studies. The clinical implications of this are potentially enormous as an estimated 1 billion people worldwide are deficient (6). Given that 90% of vitamin D is derived from sunlight (9), one way to increase levels would simply be to increase sunlight exposure, which could be made at suberythemal levels to minimize the risk of skin cancer (91). However, increasing sunlight exposure is controversial and others contend that oral dosing is preferable (92).

From a chemotherapeutic standpoint, 1,25-(OH)2D3 may prove most useful as an adjuvant treatment (93). 1,25-(OH)2D3 has the advantage over other potential melanoma treatments of being a natural product. However, hypercalcemic concerns limit its effectiveness and mean that intermittent dosing schedules are required (93). As an alternative, researchers are developing non-hypercalcemic forms of 1,25-(OH)2D3. Various non-hypercalcemic forms are currently in various stages of clinical trials, often in combination with other agents (94). Some have shown promise in the treatment of various forms of cancer (94,95). Novel metabolites of 1,25-(OH)2D3 are also being developed which show great potential (96–100). Of course, because not all melanomas express VDRs (80,81), a prerequisite for the use of 1,25-(OH)2D3 or its analogues in melanoma treatment will be a demonstration of the expression of VDRs in the melanoma being treated.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. This simplified scheme highlights mechanisms by which melanocytes can be protected against UV-induced cancerogenesis.

Acknowledgement

Supported by NIH/NIAMS grant# AR052190 to AS.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Weinstock MA. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1207–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shepherd C, Puzanov I, Sosman JA. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:146–152. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bikle D. J Nutr. 2004;134:3472S–3478S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3472S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bikle D, Oda Y, Xie Z. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann B, Querings K, Reichrath J. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13 Suppl. 4:11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2004.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holick M. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger U, Wilson P, McClelland RA, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:607–613. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-3-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel-Malek Z, Ross R, Trinkle L, et al. J Cell Physiol. 1988;136:273–280. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041360209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holick M. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:296–307. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehmann B. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:97–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann B, Tiebel O, Meurer M. Arch Dermatol Res. 1999;291:507–510. doi: 10.1007/s004030050445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zehnder D, Bland R, Williams MC, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:888–894. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankel T, Mason RS, Hersey P, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:627–631. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-3-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuster IE, Reddy GS, Schmid JA, et al. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2653–2668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bikle DD. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2357–2361. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elwood J, Gallagher RP, Hill GB, et al. Int J Cancer. 1985;35:427–433. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910350403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigel DS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:S129–S132. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noonan F, Recio JA, Takayama H, et al. Nature. 2001;413:271–272. doi: 10.1038/35095108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vollmer RT. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:260–264. doi: 10.1309/7MHX96XH3DTY32TQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berwick M, Armstrong BK, Ben-Porat L, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:195–199. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Autier P, Severi G, Boniol M, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1159. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji212. author reply 1159–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalish R. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1158. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji210. author reply 1159–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellavalle R, Johnson KR. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1158. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fears T, Tucker MA. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1789–1790. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornbuckle J, Culjak G, Jarvis E, et al. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:105–109. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200302000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray-Schopfer V, Wellbrock C, Marais R. Nature. 2007;445:851–857. doi: 10.1038/nature05661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curtin J, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtin J, Busam K, Pinkel D, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4340–4346. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mocellin S, Nitti D. Cancer. 2008;113:2398–2407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randerson-Moor J, Taylor JC, Elliott F, et al. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3271–3281. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabigting F, Nelson FP, Kauffman CL, et al. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, et al. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1155–1228. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Runger TM. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1999;15:212–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.1999.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zbytek B, Wortsman J, Slominski A. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2539–2547. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasumoto K, Yokoyama K, Takahashi K, et al. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:503–509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slominski A, Wortsman J. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:457–487. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hosoi J, Abe E, Suda T, et al. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1474–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mansur C, Gordon PR, Ray S, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:16–21. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12463282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watabe H, Soma Y, Kawa Y, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:583–589. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomita Y, Torinuki W, Tagami H. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;90:882–884. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12462151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oikawa A, Nakayasu M. FEBS Lett. 1974;42:32–35. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavlovitch J, Rizk M, Balsan S. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1982;25:295–302. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(82)90085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katayama I, Ashida M, Maeda A, et al. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:372–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes P, Brown G. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:590–617. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buitrago C, Pardo VG, de Boland AR, et al. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2199–2205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hemesath TJPE, Takemoto C, Badalian T, et al. Nature. 1998;391:298–301. doi: 10.1038/34681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu M, Hemesath TJ, Takemoto CM, et al. Genes Dev. 2000;14:301–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.An H, Yoo JY, Lee MK, et al. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2001;17:266–271. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2001.170604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brozyna A, Zbytek B, Granese J, et al. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2007;2:451–469. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swope V, Medrano EE, Smalara D, et al. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217:453–459. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Luca M, Siegrist W, Bondanza S, et al. J Cell Sci. 1993;105(Pt 4):1079–1084. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.4.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cardones A, Grichnik JM. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:441–444. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Florell S, Bowen AR, Hanks AN, et al. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00242.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patton E, Widlund HR, Kutok JL, et al. Curr Biol. 2005;15:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin J, Takata M, Murata H, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1423–1427. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pollock P, Harper UL, Hansen KS, et al. Nat Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carli P, Massi D, Santucci M, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:549–557. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bogdan I, Smolle J, Kerl H, et al. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:213–217. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000056226.78713.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li F, Ling X, Huang H, et al. Oncogene. 2005;24:1385–1395. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu G, Hu X, Chakrabarty S. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:631–639. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hong SP, Kim MJ, Jung MY, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2880–2887. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chatterjee M. Mutat Res. 2001;475:69–87. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Damian D, Kim YJ, Dixon KM, et al. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:e23–e30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedman R, Farber MJ, Warycha MA, et al. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osborne J, Hutchinson PE. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:197–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chudnovsky Y, Khavari PA, Adams AE. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:813–824. doi: 10.1172/JCI24808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cordero J, Cozzolino M, Lu Y, et al. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38965–38971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Worm M, Makki A, Dippel E, et al. Exp Dermatol. 1995;4:30–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1995.tb00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Verlinden L, Verstuyf A, Convents R, et al. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;142:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Danielsson C, Fehsel K, Polly P, et al. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:946–952. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grossman D, McNiff JM, Li F, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:1076–1081. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mamori S, Kahara F, Ohnishi K, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1497–1498. doi: 10.3109/00365520903330310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu T, Brouha B, Grossman D. Oncogene. 2004;23:39–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan H, Thomas J, Liu T, et al. Oncogene. 2006;25:6968–6974. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reichrath J, Rech M, Seifert M. J Pathol. 2003;201:335–336. doi: 10.1002/path.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shannan B, Seifert M, Leskov K, et al. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2707–2716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Busam K, Kucukgol D, Eastlake-Wade S, et al. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:619–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Colston K, Colston MJ, Feldman D. Endocrinology. 1981;108:1083–1086. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-3-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seifert M, Rech M, Meineke V, et al. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;80–90:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reichrath J, Rech M, Moeini M, et al. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:48–55. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.1.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zinser G, Sundberg JP, Welsh J. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:2103–2109. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.12.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zinser G, Suckow M, Welsh J. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chung I, Han G, Seshadri M, et al. Cancer Res. 2009;69:967–975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nurnberg B, Graber S, Gartner B, et al. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3669–3674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Newton-Bishop J, Beswick S, Randerson-Moor J, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5439–5444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Albertson D, Ylstra B, Segraves R, et al. Nat Genet. 2000;25:144–146. doi: 10.1038/75985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Parise R, Egorin MJ, Kanterewicz B, et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1819–1828. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Koynova D, Jordanova ES, Milev AD, et al. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:37–41. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3280141617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reichrath J, Rafi L, Rech M, et al. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;80–90:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Slominski A. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:154–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schulman J, Fisher DE. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:144–149. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283252fc5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Beer T, Myrthue A. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beer T, Myrthue A. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2647–2651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Blanke C, Beer TM, Todd K, et al. Invest New Drugs. 2009;27:374–378. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Slominski A, Semak I, Wortsman J, et al. FEBS J. 2006;273:2891–2901. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Slominski A, Zjawiony J, Wortsman J, et al. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:4178–4188. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Semak I, et al. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tuckey RC, Li W, Zjawiony JK, et al. FEBS J. 2008;275:2585–2596. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zmijewski MA, Li W, Zjawiony JK, et al. Steroids. 2009;74:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. This simplified scheme highlights mechanisms by which melanocytes can be protected against UV-induced cancerogenesis.