Abstract

The role of pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide (PBAN) in the regulation of pheromone biosynthesis of several female moth species is well elucidated, but its role in the males has been a mystery for over two decades since its discovery from both male and female central nervous systems. In previous studies we have identified the presence of the gene transcript for the PBAN-G-protein coupled receptor (PBAN-R) in Helicoverpa armigera male hair-pencil-aedaegus complexes (male complexes), a tissue structurally homologous to the female pheromone gland. Moreover, we showed that this transcript is up-regulated during pupal-adult development, analogous to its regulation in the female pheromone-glands, thereby indicating a likely functional gene. Here we argue in favor of PBAN’s role in regulating the free fatty-acid components (myristic, palmitic, stearic, and oleic acids) and alcohol components (hexadecanol, cis-11 hexadecanol, and octadecanol) in male complexes. We demonstrate the diel periodicity in levels of male components, with peak titers occurring during the 7th–9th h in the scotophase, coincident with female pheromone production. In addition, we show significant stimulation of component levels by synthetic HezPBAN. Furthermore, we confirm PBAN’s function in this tissue through knockdown of the PBAN-R gene using RNAi-mediated gene-silencing. Injections of PBAN-R dsRNA into the male hemocoel significantly inhibited levels of the various male components by 58%–74%. In conclusion, through gain and loss of function we revealed the functionality of the PBAN-R and the key components that are up-regulated by PBAN.

Keywords: aedaegus, hair-pencils, Helicoverpa armigera, male-produced components

Reproductive behavior involves the integration of physiological and behavioral events that synchronize male and female encounters. Receptivity in female moths is broadcasted by the release of a blend of volatile sex-pheromones during specific times of the photoperiod when they assume typical calling behaviors. In most moths this species-specific blend of pheromones is derived from downstream products of fatty-acid biosynthesis in the pheromone gland, situated between the ultimate and penultimate terminal segments of the abdomen (1, 2). Regulation of biosynthesis of these female-produced sex-pheromones is due to a photoperiodic cue initiated by the release of the neuropeptide pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide (PBAN) to the hemolymph. PBAN is recognized by its G-protein coupled transmembrane receptor (PBAN-R) (3, 4) in the female pheromone gland and stimulates the fatty-acid biosynthetic pathway (5) resulting in the stimulation of the female sex-pheromone components.

Perception of pheromones from receptive females by conspecific males initiates a typical upwind anemotaxis and orientation to the pheromone source (6). On reaching the females, males of several moth species display scent-releasing organs in the form of hair-pencils, coremata, or androconial scales (7). Hair-pencils of Lepidoptera are found in the abdominal tips which are structurally homologous to the female pheromone gland. In Lepidoptera, studies have identified hair-pencil secretions produced by several species (8–12) often with structural similarities to the conspecific female sex-pheromone components (9, 12, 13). In Helicoverpa armigera 10 components, produced in male complexes have been identified: tetradecanol, tetradecenyl acetate, myristic acid, cis-11 hexadecanol, hexadecanol, palmitic acid, hexadecenyl acetate, octadecanol, octadecenyl acetate, and stearic acid (12). The behavioral role of male secretions is not well understood, but most often these odors have been considered important in courtship behavior for close-range recognition and acceptance by the female. In general, moth male-produced pheromones are considered to have many functions, such as aphrodisiacs to stimulate female receptivity during courtship (11, 14); inducing calling behavior (15); as an arrestant of females to enable copulation (16, 17); or as a male-to-male competition inhibitor (12, 18–20). Close-range male chemical cues have also been proposed as a trait used by females to assess male quality (21).

PBAN’s function in the male has been unresolved since its discovery over two decades ago (22, 23), however PBAN-like activity is widespread among Lepidoptera as well as other invertebrate species which have peptides with the common FXPRLamide C-terminal motif (24, 25) and not all insects regulate pheromone biosynthesis using this peptide (26). PBAN-like peptides, found in other insects, have been shown to have other functions (27–32) indicating the ubiquitous and pleiotropic nature of this peptide family. Therefore, it could also be conceptualized that PBAN in male moth species will have a different function. However, in view of our recent discovery of the presence of the PBAN-R gene transcript in male complexes (4) it is tempting to reexamine the possible functional role of PBAN in the regulation of fatty-acid-derived components in this tissue. The discovery was surprising since in proteomic studies, using a binding assay, we were unable to detect the PBAN-R protein as detected in female pheromone glands (33) and thus, it may represent a nonfunctional gene. On the other hand, differential expression studies showed a temporal up-regulation of the PBAN-R gene transcript in male complexes of the two moth species, H. armigera and Bombyx mori, analogous to the up-regulation of the PBAN-R gene transcript in female pheromone glands of both species (34). Gene expression levels in the male tissue are relatively high, perhaps indicating a functional gene and the latter study, showing age-dependent transcriptional regulation of the gene, strengthens the possibility that the PBAN-R gene transcript in male complexes might represent an active functional gene. Considering the above line of reasoning, in the present study, we examine the possible role of the neuropeptide PBAN in the stimulation of putative pheromone components that are produced in male complexes by using physiological studies complemented by RNAi gene-silencing technology.

Results

Diel-Periodicity of Male Components from Male Complexes.

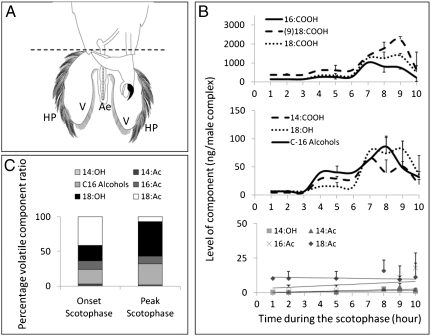

The endogenous diel rhythm of component titers from 3 d-old males was tested by extracting male complexes (Fig. 1A) at various time intervals during the scotophase. As depicted in Fig. 1B, relatively low levels of compounds were detected at the onset and early scotophase with a gradual increase to peak levels during the seventh and ninth hours, followed by a steep decline during the tenth hour. Marked photoperiodically-dependent endogenous elevations in the levels of fatty-acid components (myristic, palmitic, stearic, and oleic acids) and alcohol components (tetradecanol, hexadecanol plus cis-11 hexadecanol and octadecanol) were observed (Fig. 1B). Relatively lower levels of the acetate components were detected throughout the scotophase and no significant elevations in their levels were observed (Fig. 1B). The ratios of the volatile components during the peak hours of the scotophase (7th–9th hours) reveal that the C-16 alcohols and octadecanol are the major components that undergo an up-regulation during the scotophase when compared to their ratios at the onset of scotophase (0–2 hours, Fig. 1C). It is interesting to note that although the absolute values of octadecenyl acetate do not undergo a significant change during the photoperiod, the relative ratio of this acetate in the blend decreases significantly at the peak scotophase hours (Fig. 1C). Taken together, the results indicate a distinct diel periodicity in the levels of fatty acids and fatty-acid-derived alcohols.

Fig. 1.

Levels of components from 3 d-old male complexes during the scotophase. (A) Illustration of male complexes showing valves (V) with hair-pencils (HP) on either side of the aedaegus (Ae). Dotted line represents dissection cut line. (B) Points represent the means ± s.e.m. of 4-11 replicates. Statistically significant differences (one-way ANOVA) were found at p < 0.005 in levels of palmitic acid [16∶COOH], stearic acid [18∶COOH], myristic acid [14∶COOH], octadecanol [18∶OH], tetradecanol [14∶OH], and at p < 0.05 in levels of oleic acid [(9)18∶COOH] and hexadecanol plus cis-11 hexadecanol [C-16 Alcohols]. No significant differences were found in the acetate components: tetradecenyl acetate [14: Ac], hexadecenyl acetate [16∶Ac], and octadecenyl acetate [18∶Ac]. (C) Percentage of volatile components at onset of scotophase compared to peak scotophase.

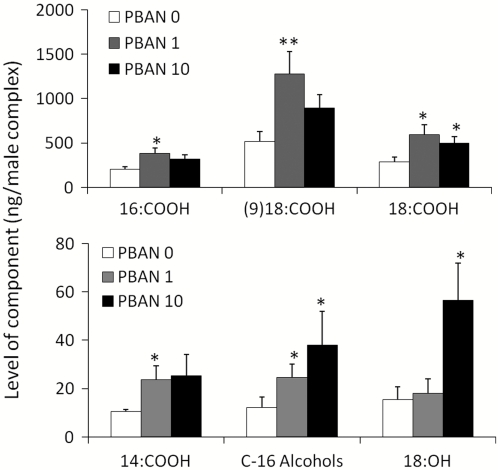

Stimulation by PBAN.

In order to test the specific effect of PBAN on male component biosynthesis, decapitated 3 d-old males were treated with PBAN at 1 pmol/male (0.1 pmol/μL) and 10 pmol/male (1 pmol/μL) and thereafter the male complexes were extracted and quantified by gas chromatograph (GC) using the internal standard method. Significant elevations in levels of several components were observed: myristic; palmitic; oleic; and stearic acids as well as the major volatile components, C-16 alcohols and octadecanol (Fig. 2). A significant stimulation for myristic, palmitic, and oleic acids was only observed at low PBAN concentrations, exhibiting a reduction in stimulation at higher PBAN concentrations. This phenomenon is similar to the response of female pheromone glands to high PBAN doses and may be attributed to steric hindrance during ligand-receptor interactions (35). The other male components (Fig. 1B) were not significantly influenced by PBAN. For an accurate quantification of free fatty acids in the samples, extracts were derivatized to the trimethylsilyl fatty acid and quantified using GC/MS and the internal standard method. For all the tested acids the percentage stimulation observed in response to 1 pmol PBAN/male (myristic 106 ± 40.4; palmitic 109 ± 40.3; oleic 211 ± 48.4; and stearic acids 128 ± 57.4) was not significantly different from the nonderivatized fatty acids (myristic 123 ± 63.9; palmitic 90 ± 63.9; oleic 148 ± 63.9; and stearic acids 109 ± 63.9), thereby confirming the validity of fatty-acid analyses performed on nonderivatized samples. The results thus verify the involvement of PBAN in stimulating the fatty-acid biosynthetic pathway and provide a strong indication that PBAN may indeed participate in an endogenous regulation of the biosynthesis of fatty-acid-derived components in the male complexes, comparable to its stimulation of the fatty-acid biosynthetic pathway in the female pheromone gland. In addition, stimulation of the volatile alcohol components emphasizes their probable functional importance in the component blend.

Fig. 2.

Effect of HezPBAN on levels of components from male complexes of 3 d-old decapitated males. Bars represent the means ± s.e.m. of 4-11 replicates. Statistically significant differences (Student t-test) are indicated with ** for p < 0.005 and * for p < 0.05. 16∶COOH = palmitic acid, (9)18∶COOH = oleic acid, 18∶COOH = stearic acid, 14∶COOH = myristic acid, C-16 Alcohols = hexadecanol plus cis-11 hexadecanol, 18∶OH = octadecanol.

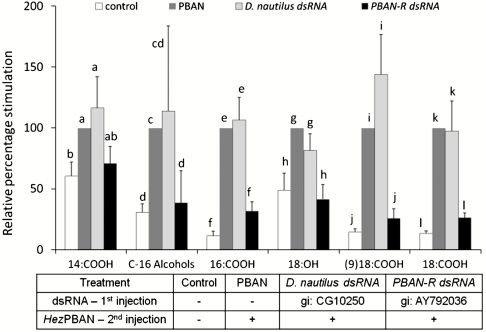

Silencing of the PBAN-R.

To substantiate PBAN’s functional role in the biosynthesis of male-produced components we used RNAi technology to knockdown the PBAN-R gene. The response to PBAN injections of males treated with PBAN-R dsRNA (10 μg/male) was compared to males injected with either RNAase-free water or the nontarget gene, Drosophila nautilus dsRNA. The treatments were also compared to control, RNAase-free water injected males, in the absence of PBAN (see table in Fig. 3). Injection of D. nautilus dsRNA or RNAase-free water did not influence the PBAN-stimulated biosynthesis of male-produced components (Fig. 3). However, major reductions due to PBAN-R dsRNA knockdown, upon injection of HezPBAN were observed in several of the components with calculated percentages of inhibition for oleic acid (74.2%), stearic acid (73.6%), palmitic acid (68.4%), and octadecanol (58.5%) (Fig. 3). These reductions reached similar levels to those observed in control, normal males that were not challenged with PBAN (Fig. 3). Clearly, knockdown of its receptor eliminated the response of male complexes to PBAN stimulation. Although levels of C-16 alcohols and myristic acid are dependent on the photoperiod and are significantly stimulated by PBAN (Figs. 1, 2), in PBAN-R dsRNA knockdown males the reductions obtained were not statistically significant when compared to the nontarget gene (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The effect of silencing the PBAN-R by injection of dsRNA in vivo on male component levels. Males that were 1 d-old were injected with RNAase-free water, D. nautilus dsRNA, or PBAN-R dsRNA. After 24 h the males were decapitated and kept in moist containers for a further 24 h for endogenous PBAN depletion and they were injected a second time with either water (as a control) or Hez-PBAN for component production analysis. The different treatments are indicated in the table below the figure. All the results are expressed as percentage stimulation relative to component levels obtained in nonRNA interference-treated males following injection of HezPBAN (10 pmol/male). The control bars represent the relative percentage levels of components from nonRNA interference-treated males in the absence of PBAN. Bars represent means ± s.e.m. of 7-8 replicates. Different letters denote a statistically significant difference for each component (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.0001). 14∶COOH = myristic acid, C-16 Alcohols = hexadecanol plus cis-11 hexadecanol, 16∶COOH = palmitic acid, 18∶OH = octadecanol, (9)18∶COOH = oleic acid, 18∶COOH = stearic acid.

Discussion

The results examining male components produced in the male complexes clearly reveal a photoperiodic cue initiating a stimulation of production of free fatty-acid and alcohol components. This diel periodicity is in contrast to reports claiming that a circadian rhythm of male component synthesis does not exist (12). However, the latter report does not provide substantial evidence of a precise quantification at various times of the photoperiod and merely claims that at any time it is possible to extract the compounds. In truth, unlike female sex-pheromone components the male components are present at all times tested. However, in this study we show that their relative levels change drastically during the scotophase and reach maximum levels at a time window in which reproductive behavior is at its peak. Since PBAN is known as a circadian signal for the production and stimulation of female sex-pheromone components we hypothesized that it may have a similar role for male fatty-acid-derived components. Indeed, our biological assays and gene-silencing experiments reveal that PBAN plays an essential role in the stimulation of male-produced components in male complexes and explain the presence and functional significance of the PBAN-R in this tissue.

We confirm the presence of the 10 components previously identified in H. armigera males (12) with the additional presence of oleic acid. Out of these 10 components, all the free fatty acids, the C-16-Alcohols, and octadecanol responded to PBAN stimulation. Our studies divulged the importance of the alcohol components in male complexes by demonstrating both a precise diel periodicity and a significant specific response to PBAN. Alcohol components have been implicated in male-male inhibition and female receptivity. Sensitivity of olfactory receptor neurons in females to hexadecanol and sensitivity to octadecanol in both males and females was demonstrated (36), thus indicating their behavioral relevance. An increase in female abdominal extension, indicating sexual excitement and readiness to mate (19) in response to the hexadecanol and octadecanol components of male complexes was observed in Heliothis virescens (17). High levels of cis-11 hexadecanol in traps containing a female sex-pheromone blend significantly reduced captures of H. armigera and H. virescens males (19, 37) and inhibited male orientation behavior in a wind tunnel (20, 38) thus implicating its role in inhibiting male-male competition. Our observations highlight octadecanol as a major component in male complexes where increased levels at the peak scotophase are concomitant with a decrease in the relative ratio of octadecyl acetate. This increase in octadecanol levels might indicate the acetate's possible role as precursor to the alcohol component produced through the action of an acetate esterase, as was demonstrated in H. virescens (9).

In addition, the free fatty acids may represent the precursors for the alcohol and acetate components or, in themselves, also elicit behavioral responses. Free fatty acids in the lipid layer of the insect's cuticle play an important role in preventing water loss but are also mostly regarded as precursors to pheromone components (39). However, growing evidence has accumulated indicating that some free fatty acids can act as major players in chemical communication systems. Free fatty acids have been known to act as contact pheromones in a number of insect species. Palmitic and stearic acids, for example, were reported to participate in the chemical camouflage of a moth in honeybee colonies (40). In a study on the Hemipteran Triatoma infestans, stearic acid showed a significant assembling effect and was thus implicated as an aggregation pheromone (41). Free fatty acids have also been shown to act as oviposition attractants (oleic and linoleic acids) (42) or as repellents/deterrents (palmitic, oleic, linoleic, and linolenic acids) (43, 44). Furthermore, stearic and palmitic acids act as sex pheromones in the tick Dermacentor variabilis (45). In addition, oleic acid has been implicated as the fatty acid responsible for a necrophoric effect in some ant species (46, 47) and free fatty acids are central in predator avoidance, conspecific attraction, and food recognition in the Collembola, Protaphorura armata (48). Moreover, palmitic acid, present in male complexes of the moth, Adoxophyes orana acts as a male-male inhibitory pheromone component (49). An additional role for free fatty acids was shown in H. armigera where calling behavior and mating rate were reduced significantly when females were exposed to oleic acid and several other free fatty acids (50).

Conclusive evidence for the functionality of PBAN in the biosynthesis of male components was obtained by PBAN-R gene-silencing demonstrating a loss of function where component levels were drastically reduced in PBAN-R dsRNA knockdown males. We suggest that those components that are responsive to PBAN and photoperiod, and are significantly affected by loss of function of the PBAN-R are most probably the key components in chemical communication between females and males during copulation.

Our results thus indicate the feasibility that PBAN, the photoperiodic cue in both males and in females would be utilized at the same time to increase the attractiveness of the female and allow for a synchronized and successful mating encounter by up-regulating components in male complexes. We revealed the functionality of the PBAN-R gene transcript and the key components that are up-regulated by PBAN through gain and loss of function. Our study clearly demonstrated the power of RNAi technology for reexamining unanswered questions from two decades ago. It remains to be demonstrated that those PBAN up-regulated male-produced compounds are indeed responsible for a successful mating encounter by either arresting females for copulation, increasing their receptivity, or deterring conspecific males from competing. We expect that our findings will impact on a more complete understanding of synchronized mating behavior and the molecular mechanisms involved therein in other Lepidoptera species.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Synthetic HezPBAN was custom synthesized by Peptide 2. Standard fatty acids, pheromone components, N,O-bis (trimethylsilyl) trifluroacetamide (BSTFA), and trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For male complex extractions, n-hexane was purchased from Carlo Erba Reagent. For dsRNA synthesis a Megascript RNAi kit was used, purchased from Ambion.

Insect Culture.

Helicoverpa armigera were raised on an artificial diet as previously reported (34).

Male Complex Component Extractions, Derivatization, and Gas Chromatographic Analysis.

Male complexes were dissected and extracted in hexane for 30 min at room temperature from 3 d-old adult males (1 male equivalent/100 μL) containing 100 nanograms undecyl acetate as internal standard. The extract was passed through a glass-wool filter in a Pasteur pipette and evaporated to 5 μL. The extracts were analyzed on a Shimadzu (GC 17A Model) GC using splitless mode on a EC-5 (Econo-Cap 30m, 0.25 mm ID, Alltech) column using the following conditions: The initial temperature of 120 °C was held for 2 min then increased to a final temperature of 280 °C at 5 °C/ min maintained for 30 min. The flame-ionization detector temperature was held at 300 °C and the column inlet temperature at 280 °C. Helium gas was used as the carrier gas at a column flow rate of 1.3 mL/ min with velocity at 33 cm/ sec. Components in male complex extracts were identified according to the retention times of standard components: Undecyl acetate (internal standard) at 11.15 min; tetradecenol (14∶OH) at 15.48 min; myristic acid (tetradecanoic acid, 14∶COOH) at 17.34 min; tetradecyl acetate (14∶Ac) at 18.42 min; cis-11 hexadecanol at 20.19 min; hexadecanol at 20.34 min; palmitic acid (hexadecanoic acid, 16∶COOH) at 21.71 min; hexadecyl acetate (16∶Ac) at 22.77 min; octadecanol (18:OH) at 24.63 min; oleic acid (cis-9 octadecenoic acid, (9)18∶COOH) at 25.32 min; stearic acid (octadecanoic acid, 18∶COOH) at 25.73 min; and octadecyl acetate (18∶Ac) at 26.78 min. All components in male complexes were analyzed according to the internal standard method (51). Derivatization of the acid components in male complexes was performed using a BSTFA + TMCS kit (99∶1) as silylation reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol using pooled extracts of 10 male equivalents and their chemical identities were validated using GC/MS. Hexadecanol and cis-11 hexadecanol are reported to be present at a ratio of 95∶5 (12). Our elution profiles show that these two components are separated by only 0.15 min, therefore for accuracy, during GC analysis the calculations were made as the sum of the two components (hereby referred to as C-16 alcohols) using the internal standard method of calculation.

Pheromonotropic Assay In vivo.

Males (2 d-old) were decapitated during the photophase and kept in moist containers for 24 h for a complete depletion of their endogenous PBAN. After 24 h they were either injected with 10 μL double distilled water or with 10 μL dissolved Hez-PBAN (0.1 pmol/μL or 1 pmol/μL) into the hemocoel between the sixth and seventh abdominal segments. After 2 h of incubation the male complexes were dissected and extracted as mentioned above.

dsRNA Synthesis and Silencing Experiments.

The method used to synthesize dsRNA is similar to that described by Meister and Tuschl (52) with slight modifications. The PBAN-R primers corresponding to 880 base pairs of the ORF that was previously identified in male complexes (4), were used to amplify exons of the HeaPBAN-R gene (AY792036) from total cDNA which was prepared from female pheromone glands using the same RT-PCR thermocycling reaction program as described previously (4). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out using the specific PBAN-R primers (4) conjugated with 27 bases of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACCAC-3′. One μg of the PCR products and the control template (supplied in the kit) of the nontarget Drosophila nautilis protein coding gene (CG10250) (encoding a transcription factor that is involved in muscle development in Drosophila embryos and referred herein as D. nautilus dsRNA), were used as templates for dsRNA in vitro synthesis using the Megascript RNAi kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After synthesis, the dsRNA was quantified using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc.) and the products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis to confirm annealing. The annealed dsRNA was kept at -20 °C and before injection it was thawed on ice and 10 μL (1 μg/μL) was injected into the hemocoel between the sixth and seventh abdominal segments of 1 d-old males during the photophase. Males who were 1 d-old were initially injected with RNAase-free water (Qiagen Inc.), D. nautilus dsRNA, or PBAN-R dsRNA. After 24 h the males were decapitated and kept in moist containers for a further 24 h for endogenous PBAN depletion. Subsequently, the response to PBAN was tested by a second injection into the hemocoel of either double distilled water (as a control) or Hez-PBAN and male complex extracts were analyzed as described above (see table in Fig. 3.).

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statview 4.01 package on a Macintosh computer using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student’s t-test.

Acknowledgments.

We thank Avihu Azrielli for technical assistance. We also thank Daniela Fefer for validation of compounds on GC/MS and Lea Katzir for illustration of the male complex. This research represents a part of the Ph. D. Dissertation by R.B. The research was supported by a research grant award IS-4163-08C from the United States-Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund. This is contribution No. 585/10 from the Agricultural Research Organization, Volcani Center, Bet Dagan, Israel.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Rafaeli A. Neuroendocrine control of pheromone biosynthesis in moths. Int Rev Cytol. 2002;213:49–92. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(02)13012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rafaeli A. Pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide (PBAN): regulatory role and mode of action. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;162:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi M-Y, Fuerst E-J, Rafaeli A, Jurenka RA. Identification of PBAN-GPCR, a G-protein-coupled-receptor for pheromone biosynthesis-activating neuropeptide from pheromone glands of Helicoverpa zea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9721–9726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1632485100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafaeli A, et al. Spatial distribution and differential expression of the receptor for pheromone-biosynthesis-activating neuropeptide (PBAN-R) at the protein and gene levels in tissues of adult Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsfadia O, et al. Pheromone biosynthetic pathways: PBAN-regulated rate-limiting steps and differential expression of desaturase genes in moth species. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:552–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker TC, Willis MA, Haynes KF, Phelan PL. A pulsed cloud of sex pheromone elicits upwind flight in male moths. Physiol Entomol. 1985;10:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birch MC, Poppy GM, Baker TC. Scents and eversible scent structures of male moths. Ann Rev Entomol. 1990;35:25–58. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phelan PL, Silk PJ, Northcott CJ, Tan SH, Baker TC. Chemical identification and behavioral characterization of male wing pheromone of Ephestia elutella (Pyralidae) J Chem Ecol. 1986;12:135–146. doi: 10.1007/BF01045597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teal PEA, Tumlinson JH. Isolation, identification, and biosynthesis of compounds produced by male hairpencil glands of Heliothis virescens (F.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) J Chem Ecol. 1989;15:413–427. doi: 10.1007/BF02027801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heath RR, Landolt PJ, Dueben BD, Murphy RE, Schneider RE. Identification of male cabbage looper sex pheromone attractive to females. J Chem Ecol. 1992;18:441–453. doi: 10.1007/BF00994243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thibout E, Ferary S, Auger J. Nature and role of sexual pheromones emitted by males of Ascrolepiopsis assectella (Lep.) J Chem Ecol. 1994;20:1571–1581. doi: 10.1007/BF02059881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Xu S, Tang X, Zhao Z, Du J. Male orientation inhibitor of cotton bollworm: identification of compounds produced by male hairpencil glands. Entomologia Sinica. 1996;3:172–182. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lassance J-M, Lofstedt C. Concerted evolution of male and female display traits in the European corn borer. BioMed Central Biology. 2009;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-10. 10.1186/1741-7007-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birch MC. In: Pheromones. Birch MC, editor. North Holland: Amsterdam; 1974. pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szentesi A, Toth M, Dodrovolsky A. Evidence and preliminary investigation on a male aphrodisiac and a female sex pheromone in Mamestra brassicae (L.) Acta Phytopathl Hun. 1975;10:425–429. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teal PEA, McLaughlin JR, Tumlinson JH. Analysis of the reproductive behavior of Heliothis virescens (F.) under laboratory conditions. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1981;74:324–330. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillier NK, Vickers NJ. The role of Heliothine hairpencil compounds in female Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) behavior and mate acceptance. Chem Senses. 2004;29:499–511. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirai K, Shorey HH, Gaston LK. Competition among courting male moths: male-to-male inhibitory pheromone. Science. 1978;202:844–845. doi: 10.1126/science.202.4368.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teal PEA, Tumlinson JH, Mclaughlin FR, Heath RR, Rush RA. (Z)-11-hexadecanol: a behavioral modifying chemical present in the pheromone gland of female Heliothis zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Can Entomol. 1984;116:777–779. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang YP, Xu SF, Tang XH, Zhao ZW, Du JW. Male orientation inhibitor of cotton bollworm: inhibitory effects of alcohols in wind-tunnel and in the field. Entomologia Sinica. 1997;4:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisner T, Meinwald J. The chemistry of sexual selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:50–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raina AK, Klun JA. Brain factor control of sex pheromone production in the female corn earworm moth. Science. 1984;225:531–533. doi: 10.1126/science.225.4661.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingan TG, Blackburn MB, Raina AK. The distribution of pheromone-biosynthesis-activating neuropeptide (PBAN) immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the corn earworm moth, Helicoverpa zea. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;270:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gäde G, Hoffmann KH, Spring JH. Hormonal regulation in insects: Facts, gaps, and future directions. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:963–1032. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torfs P, et al. Pyrokinin neuropeptides in crusacean. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:149–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jurenka JA. Insect pheromone biosynthesis. Topics Curr Chem. 2004;239:97–132. doi: 10.1007/b95450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holman GM, Cook BJ, Nachman RJ. Isolation, primary structure, and synthesis of a blocked myotropic neuropeptide isolated from the cockroach, Leucophaea maderae. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1986;85C:219–224. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(86)90077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto S, et al. Functional diversity of a neurohormone produced by the suboesophageal ganglion: molecular identity of melanization and reddish coloration hormone and pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide. J Insect Physiol. 1990;36:427–432. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imai K, et al. Isolation and structure of diapause hormone of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. P Jpn Acad. 1991;67B:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zdarek J, Nachman RJ, Hayes TK. Insect neuropeptides of the pyrokinin/PBAN family accelerate pupariation in the fleshfly (Sarcophaga bullata) larvae. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;814:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb46145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu J, et al. The diapause hormone-pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide gene of Helicoverpa armigera encodes multiple peptides that break, rather than induce, diapause. J Insect Physiol. 2004;50:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe K, et al. FXPRL-amide peptides induce ecdysteroidogenesis through a G-protein coupled receptor expressed in the prothoracic gland of Bombyx mori. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;273:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rafaeli A, Zakarova T, Lapsker Z, Jurenka RA. The identification of an age- and female-specific putative PBAN membrane-receptor protein in pheromone glands of Helicoverpa armigera: Possible up regulation by juvenile hormone. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:371–380. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bober R, Azrielli A, Rafaeli A. Developmental regulation of the pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide-receptor (PBAN-R): re-evaluating the role of juvenile hormone. Insect Mol Biol. 2010;19:77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bober R, Rafaeli A. In: Short views on insect molecular biology. Krishnan M, Chandrasekar K, editors. South India: International Book Mission, Academic Publisher; 2009. pp. 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hiller NK, Kelineidam C, Vickers NJ. Physiology and glomerular projections of olfactory receptor neurons on the antenna of female Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) responsive to behaviorally relevant odors. J Comp Physiol A. 2006;192:199–219. doi: 10.1007/s00359-005-0061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kehat M, Gothielf S, Dunkelblum E, Greenberg S. Field evaluation of female sex pheromone components of the cotton bollworm, Heliothis armigera. Entomol Exp Appl. 1980;27:188–193. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kehat M, Dunkelblum E. Behavioral responses of male Heliothis armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) moths in a flight tunnel to combinations of components identified from female sex pheromone glands. J Insect Behav. 1990;3:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tillman JA, Seybold SJ, Jurenka RA, Blomquist GJ. Insect pheromones—an overview of biosynthesis and endocrine regulation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;29:481–514. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moritz RFA, Kirchner WH, Crewe RM. Chemical camouflage of the death’s head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos L.) in honeybee colonies. Naturwissenschaften. 1991;78:179–182. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Figueiras ANL, Girotti JR, Mijailovsky SJ, Juarez MP. Epicuticular lipids induce aggregation in Chagas disease vectors. BioMed Central Parasites and Vector. 2009;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-2-8. 10.1186/1756-3305-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phelan PL, Roelofs CJ, Youngman RR, Baker TC. Characterization of chemicals mediating ovipositional host-plant finding by Amyelois transitella females. J Chem Ecol. 1991;17:599–613. doi: 10.1007/BF00982129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gabel B, Thiery D. Oviposition response of Lobesia botrana females to long-chain free fatty acids and esters from its eggs. J Chem Ecol. 1996;22:161–171. doi: 10.1007/BF02040207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li G, Ishikawa Y. Oviposition deterrents from the egg masses of the adzuki bean borer,Ostrinia scapulali and Asian corn borer O furnacalis. Entomol Expt Appl. 2005;115:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allan SA, Philips JS, Sonenshine DE. Species recognition elicited by differences in composition of the genital sex pheromone in Dermacentor variabilis and D. andersoni (Acari: Ixodidae) J Med Entomol. 1989;26:539–546. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/26.6.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haskins CP, Haskins EF. Notes on necrophoric behavior in the archaic ant Myrmecia vindex. Psyche. 1974;81:258–267. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blum MS. In: Chemicals controlling insect behavior. Beroza M, editor. New York: Academic Press; 1970. pp. 61–94. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nilsson E, Bengtsson G. Endogenous free fatty acids repel and attract Collembola. J Chem Ecol. 2004;30:1431–1443. doi: 10.1023/b:joec.0000037749.75695.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Den Otter CJ, Bruins AP, Hendriks H, Bijpost SCA. Palmitic acid as a component of the male-to-male inhibitory pheromone of the summerfruit tortricid moth, Adoxophyes orana. Entomol Exp Appl. 1989;52:291–294. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dong WX, Han BY, Du JW. Inhibiting the sexual behavior of female cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera. J Insect Behav. 2005;18:453–463. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rafaeli A, Soroker V. Influence of diel rhythm and brain hormone on pheromone production in two Lepidopteran species. J Chem Ecol. 1989;15:447–455. doi: 10.1007/BF01014691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meister G, Tuschl T. Mechanisms of gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nature. 2004;431:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature02873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]