Abstract

We assessed determinants of condom use postulated by the IMB model among STD patients (N = 1,474). The model provided acceptable fit to the data (CFI = .99, RMSEA = .04). Information was unrelated to condom use but had a negative effect on behavioral skills. Motivation had a positive effect on behavioral skills and condom use. Behavioral skills had a positive effect on condom use. In multiple-groups analyses, stronger associations between motivation and condom use were found among participants reporting no prior STD treatment. Interventions among STD patients should include activities addressing condom use motivation and directly enhancing condom skills.

Keywords: STD, HIV, IMB, sexual risk behavior, condoms

INTRODUCTION

In comparison to community samples, patients at STD clinics report riskier health behaviors including elevated substance use that may exacerbate sexual risk (Cook, et al., 2006; Howards, Thomas, & Earp, 2002). Not only do STD clinic patients report riskier behaviors, they are more likely to acquire multiple STDs, inadvertently sustaining STDs in their communities (Leichliter, Ellen, & Gunn, 2007). Because STD clinic patients are more susceptible to HIV (Weinstock, Sweeney, Satten, & Gwinn, 1998), and because STDs increase the risk of transmitting HIV to a partner (CDC, 2007a), identifying determinants of condom use among STD patients can facilitate the prevention of HIV. Examining condom use, including factors known to be related to HIV-preventative behavior, can guide intervention development to reduce new infections.

The current study uses the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model (J. D. Fisher & Fisher, 1992) to understand condom use among STD clinic patients. The IMB model conceptualizes information, motivation, and behavioral skills as fundamental determinants of HIV-preventive behavior and specifies causal relations among the constructs. According to the model, informed and motivated individuals acquire the requisite behavioral skills to reduce risk behavior whereas uninformed and unmotivated people lack the skills needed for risk reduction. The model proposes that the association between information and motivation to behavior is mediated by behavioral skills but information and motivation may have a direct effect on behavior.

Research examining the IMB model's assumptions in a variety of populations (e.g., college students, gay men, substance abusing mentally ill adults) has generally supported the model's assertions that information and motivation are associated with the initiation and maintenance of behavioral skills, and having the requisite behavioral skills are, in turn, associated with increased prevention behavior (J. D. Fisher, Fisher, & Shuper, 2009). Furthermore, motivation to reduce HIV risk has a direct effect on preventative behavior. Associations between information and behavior and information and behavioral skills, however, have been inconsistent (J. D. Fisher, et al., 2009). These inconsistencies may be due to (a) methodological problems (e.g, , restricted sampling, inadequate measurement), or (b) the nature of the behavior (e.g., simple vs. complex behaviors such as abstinence vs. acquiring and negotiating condom use). Nonetheless, research has shown the model's constructs explain one-third to one-half of the variance in condom use (Bryan, Fisher, & Benziger, 2001; Bryan, Fisher, Fisher, & Murray, 2000). Moreover, the model has been supported as an effective intervention among multiple populations (e.g., HIV+ patients; J. D. Fisher, et al., 2009).

The purpose of the study is to examine determinants of condom use postulated by the IMB model among adult STD clinic patients. We used structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques to examine the associations between HIV-related information, motivation, and behavioral skills for condom use. We also examine differences between patients reporting prior STD treatment versus those without prior treatment. Consistent with previous research examining condom use among at-risk populations (Bryan, et al., 2001; Bryan, et al., 2000; Robertson, Stein, & Baird-Thomas, 2006), we expect motivation to have a direct effect on behavioral skills and both motivation and behavioral skills to have direct effects on condom use. Because the IMB model suggests that acquiring a STD may increase both personal and social motivation to reduce risk behavior (J. D. Fisher, et al., 2009), we expect to find difference regarding condom use motivation based on STD treatment history. Given the inconsistencies found for information, we made no predictions regarding the information-behavioral skills and information-behavior associations.

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

Patients were recruited for a randomized clinical trial (RCT) evaluating interventions to reduce sexual risk among STD patients (Carey, Senn, Vanable, Coury-Doniger, & Urban, 2008; Carey, Vanable, Senn, Coury-Doniger, & Urban, 2008). To be eligible for the RCT, patients needed to report (a) age 18 or older; (b) sexual risk behavior during the past 90 days (i.e., vaginal or anal sex without a condom, having more than one sexual partner, having a STD, or having a sex partner who had other partners, injected drugs, or was diagnosed with HIV or other STD); and (c) willingness to be tested for HIV. Patients were excluded if they were (a) infected with HIV (referred for more comprehensive services); (b) impaired (i.e., substance use, mental illness); (c) receiving inpatient substance abuse treatment; and (d) planning on moving within the next year. Eligible patients met with a research assistant (RA) and were given details about the study. Interested patients provided written consent (n = 1,559), completed an audio-computer assisted self-interview (ACASI) on a laptop computer, and were reimbursed $20 for their time.

Of the 1,559 patients who consented, 14 withdrew, 8 tested positive for HIV and were referred, and 54 were part of a pilot leaving 1,483 participants (46% female, 64% African-American, M age = 29 years). The protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions and, to protect participant privacy, a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained.

Measures

Baseline surveys assessed (a) demographic information (e.g., gender ethnicity, age), (b) sexual history, (c) IMB constructs (e.g., HIV knowledge, condom attitudes), and (d) additional measures (e.g., alcohol and drug use) as part of the larger RCT. All questions have been used in previous research (Carey, et al., 2000; Carey, et al., 2004; Carey, et al., 1997).

HIV/STD Information

Information was assessed using the Brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire (HIV-KQ-18) (Carey & Schroder, 2002) supplemented with 6 items adapted from the STD-Knowledge Questionnaire (STD-KQ) (Jaworski & Carey, 2007). Correct responses were coded as 1 and incorrect or uncertain responses were coded as 0. Consistent with recommendations for dealing with dichotomous variables (Floyd & Widaman, 1995), the intercorrelations of the items were examined and items showing high inter-correlations were combined to form four indicators: (a) non-sexual transmission information (6 items; e.g., “Can coughing and sneezing spread HIV?”, K-R 20 = 0.71), (b) sexual transmission information (7 items; e.g., “Can a woman get HIV if she has anal sex with a man?”, K-R 20 = 0.63), (c) information related to signs and symptoms of STDs (8 items; e.g., “Do people who have been infected with HIV quickly show serious signs of being infected?”, K-R 20 = 0.62), and (d) condom information (3 items; e.g., “Does a natural skin condom work better against HIV than a latex condom?, K-R 20 = 0.49).

Motivation

Motivation was measured using condom attitudes and condom use intentions. Condom attitudes were assessed using 5 items (e.g., “Sex with a condom can still be pleasurable.”) adapted from published scales (Brown, 1984; Sacco, Levine, Reed, & Thompson, 1991). Response choices were on a 6-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Items were averaged to create a condom attitudes score (α= .69) with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes toward condoms. Condom intentions were assessed using one item: “I would refuse to have sex if we didn’t use a condom.” Participants rated their intentions using a 4-point scale ranging from “definitely no” to “definitely yes.” Higher scores indicate greater intentions to use condoms.

Behavioral Skills

Behavioral skills were measured using 7 items (e.g., “I refused to have sex with my partner unless a condom was used”) from the Condom Influence Strategy Questionnaire (CISQ) (Noar, Morokoff, & Harlow, 2004b). Response choices were on a 5-point scale ranging from “never” to “almost always.” Items were averaged to create a total score (α= 0.89) with higher scores indicating the use of more skills. Previous research found community members who used a condom the last time they had sex reported higher CISQ scores (Noar, Morokoff, & Harlow, 2004a).

Behavior

Condom use (in past 3 months) was assessed by asking participants how often they had (a) vaginal sex with a condom, (b) vaginal sex without a condom, (c) anal sex with a condom, and (d) anal sex without a condom. Responses were used to determine the proportion of protected sexual events in past 3 months (number of times vaginal and anal sex occurred with a condom divided by the total number of vaginal and anal sexual events).

Data Management and Analysis

We removed 9 (<1%) participants due to excessive missing data (i.e., no responses given for all items used to measure a latent construct). All variables were examined for univariate and multivariate outliers by inspecting box plots and conducting the Mahalanobis distance statistic (d2). Univariate outliers were recoded to a value three standard deviations from the mean (Kline, 2005). No multivariate outliers were observed.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and SEM were conducted using AMOS 16 (Arbuckle, 2007). Because the data were normally distributed, we used maximum likelihood estimation (ML). We evaluated a CFA measurement model (MM) which included two hypothesized latent constructs (information, motivation) predicting its proposed indicators (information: non-sexual transmission, sexual transmission, signs and symptoms, condoms; motivation: condom attitudes, intentions) and two manifest constructs (condom skills, condom use); all constructs were correlated. Once an acceptable MM was established, we evaluated a structural model in which information and motivation predicted condom skills and all IMB constructs predicted proportion of condom use in the overall sample and by STD treatment subgroup.

Model fit was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and χ2/df ratio (Kline, 2005). The CFI compares the proportion of improvement in the model relative to a null model; values greater than .95 indicate a good fit. The RMSEA accounts for model complexity; values less than .05 indicating a good fit. Finally, we report the χ2, degrees of freedom, and the ratio. A good fitting model is assumed when χ2 is non-significant; however, χ2 is sensitive to sample size, therefore, χ2 is divided by the degrees of freedom with a ratio of 3 or less indicating acceptable fit (Kline, 2005).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Sample

The sample comprised was 1,474 patients (47% female, 64% African-American, M age = 29 years). Most participants had a high school education or less (62%), were unemployed (51%), and had an annual income of less than $15,000 (56%). In the past 3 months, participants reported an average of 2.81 (SD = 2.21, Mdn = 2.00) sexual partners, an average of 17.28 (SD = 21.21; Mdn = 9.00) episodes of unprotected sex (steady partners: M = 14.02, SD = 20.14, Mdn = 6.00; casual partners: M = 2.82, SD = 4.31, Mdn = 1.00), and 28% of participants reported drinking prior to their last sexual occasion. Most participants reported only having vaginal sex (71%), few reported only anal sex (0.5%), and some reported both vaginal and anal sex (29%). Participants reported being treated for an STD an average of 3.26 times (SD = 3.89; Mdn = 2.00) in their lifetime with 23% diagnosed with one or more incident STD (165, 130, and 90 cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis respectively) at baseline.

Participants were generally knowledgeable about STD prevention (51% to 94% correct responses to the 24 items). Most correctly responded to questions regarding non-sexual transmission (75%; M = 4.23, SD = 1.67), sexual transmission (78%; M = 5.61, SD = 1.36), condom use (62%; M = 4.49, SD = 1.43), and signs and symptoms of HIV (75%; M = 1.87, SD = 0.98). Participants reported positive attitudes regarding condom use (M = 4.46, SD = 0.93) and intended to use a condom (M = 3.17, SD = 0.97). Condom use behavioral skills, assessing communication and negotiation of condoms, were reported some of the time (M = 2.40, SD = 1.11). Finally, participants reported using condoms 34% of the time (SD = 0.33).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

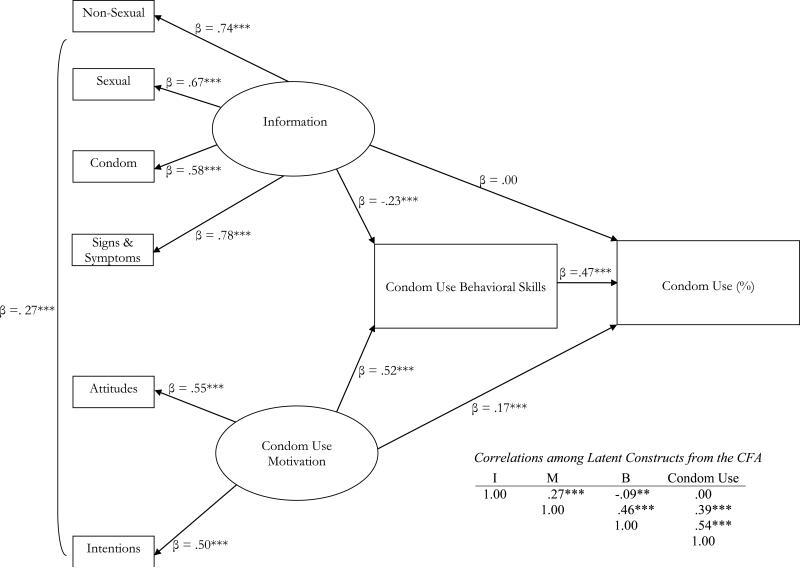

To establish whether the IMB items represented distinct latent constructs and assess the adequacy of the proposed MM, we conducted a CFA. All parameter estimates were significant (p <.001), with indices indicated a good fitting model (CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = .04; χ2 = 46.67, df = 16, χ2/df = 2.92). Correlations among the latent variables derived from the CFA are presented in Figure 1. All latent constructs were correlated except for information and condom use (r = <.01, p >.05). Given the overall fit of the data to the model, no additional paths or covariances were added.

Figure 1.

Structural equation modeling of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model constructs predicting condom use among STD clinic patients (N = 1,474). Path coefficients are standardized. ***p <.001. I = Information; M = Motivation; B = Behavioral Skills.

Full Structural Model

SEM analysis was performed using ML estimates. The model fit the data well (CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = .04; χ2 = 46.67, df = 16, χ2/df = 2.92; see Figure 1). As expected, behavioral skills (β = .47, p <.001) and motivation (β = .17, p <.001) had positive effects on condom use; motivation also had a positive effect on behavioral skills (β = .52, p <.001). Contrary to the IMB model, information was negatively related to behavioral skills (β = -.23, p <.001) and was not related to condom use (β = <.01, p >.05).1 In combination, these variables accounted for 32% of the variation in condom use.

Multiple-Group Analysis

Separate models were estimated among participants who reported receiving past STD treatment (n = 1124) and those who did not (n = 350).2 Models for participants reporting past STD treatment (CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = .03; χ2 [16] = 30.07, χ2/df = 1.88) and those with no history of STDs (CFI = 0.98; RMSEA = .05; χ2 [16] = 28.75, χ2/df = 1.80) fit the data well. Table 2 reports the path coefficients between the IMB constructs for those reporting past treatment for STDs and those who did not. Among both groups, behavioral skills and motivation predicted condom use; motivation also predicted behavioral skills. Consistent with the model of overall condom use, information was negatively related to behavioral skills and was unrelated to condom use. These models explained 29% and 47% of the variance respectively.

Table 2.

Multiple Group Analyses Comparing Participants Reporting Prior STD Treatment (n = 1124) Versus those with No Prior STD Treatment (n = 350)

| Model | Comparison Model | χ 2 | df | χ2/df | χ 2diff | Δ df | p | RMSEA | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Unconstrained multiple group model | -- | 58.85 | 32 | 1.84 | -- | -- | -- | .024 | .989 |

| 2. Constrained multiple group model | 1 | 81.44 | 44 | 1.85 | 22.59 | 12 | .031 | .024 | .985 |

| 3. Factor loadings constrained equal | 1 | 59.66 | 36 | 1.66 | 0.81 | 4 | .938 | .021 | .991 |

| 4. Factor loadings, I, M, and BS paths constrained equal. | 3 | 74.34 | 41 | 1.81 | 14.68 | 5 | .012 | .024 | .987 |

| 5. Factor loadings and I paths constrained equal | 3 | 60.95 | 38 | 1.60 | 1.29 | 2 | .525 | .020 | .991 |

| 6. Factor loadings, I and M paths constrained equal | 5 | 73.51 | 40 | 1.84 | 12.56 | 2 | .002 | .024 | .987 |

| 7. Factor loadings, I paths, and M-BS constrained equal | 5 | 64.02 | 39 | 1.64 | 3.07 | 1 | .078 | .021 | .990 |

| 8. Factor loadings, I paths, and M-B constrained equal | 5 | 72.84 | 39 | 1.87 | 11.89 | 1 | .001 | .024 | .987 |

| 9. Factor loadings, I, M-BS, and BS paths constrained equal | 7 | 65.84 | 40 | 1.65 | 1.82 | 1 | .177 | .021 | .990 |

Note. I = information; M = motivation; BS = behavioral skills; B = behavior; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index.

To further examine the differences between participants who had or had not been previously treated for a STD, we tested the model for multiple group invariance (Byrne, 2001; Kenny, 2008). Goodness-of-fit statistics and the χ2 difference test assessed the models (see Table 3). First, we tested the validity of the IMB model across groups (i.e., unconstrained multiple-group model). As shown in Table 3, the unconstrained multiple-groups model (Model 1) indicates that the data are well-fitting across groups. Next, we tested the invariance of the structural model (i.e., constrained multiple-groups model) where the factors, paths, variances, covariance, and errors covariances were constrained to be equal across the two groups. Comparisons between Model 1 and the constrained multiple-groups model (Model 2) indicate that as least one constraint is unequal across groups (χ2 difference = 22.59, Δdf = 12, p = .03).

To determine the source(s) of the noninvariance, invariance of the factor loadings (FL) and paths were examined in two models. Results comparing the invariance of the FL (Model 3) with Model 1 indicate that the FL were not invariant (χ2 difference = 0.81, Δdf = 4, p = .94). For the model examining the invariance of paths (Model 4), the paths were invariant across groups (χ2 difference = 14.68, Δdf = 5, p = .01). Thus, paths were examined individually in separate models. Across models (Models 5 through 9), a significant group difference was found for the motivation-behavior path. A t test was computed to test the differences between the unstandardized coefficients (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). A significant difference between the groups for the motivation-behavior path was found, t (1472) = 2.19, p = .03, indicating a stronger association between motivation and condom use among those who had not been previously treated for STDs compared to those who had. All other paths were invariant between groups.

DISCUSSION

The IMB model provides a framework to further understanding of the determinants of condom use in a STD clinic sample. Reducing sexual risk behavior among clients of an STD clinic is important because such clients are at substantial risk of contracting HIV and other STDs and sustaining STDs throughout their communities (CDC, 2007b; Leichliter, et al., 2007). Although empirical tests of the IMB model for condom use have been conducted with heroin addicts (Bryan, et al., 2000), Indian truck drivers (Bryan, et al., 2001), and incarcerated juvenile offenders (Robertson, et al., 2006), the current study is the first to examine the determinants of condom use with this framework among STD clinic patients who have had prior STD treatment compared to those who had not been previously treated for a STD. Overall, the IMB model fit the data well and accounted for 32% (29% among patients with prior STD treatment, 47% among patients with no prior STD treatment) of the variability in condom use. Results from the SEM supported some, but not all, of the associations between information, motivation, and behavioral skills to condom use.

Contrary to the IMB model, information was negatively associated with behavioral skills and showed no association with condom use. Prior research examining the IMB model has found inconsistencies in the associations between information and behavioral skills (Anderson, et al., 2006; Bryan, et al., 2001; W. A. Fisher, Williams, Fisher, & Malloy, 1999) and information and HIV-preventative behavior (J. D. Fisher, Fisher, Williams, & Malloy, 1994; S. C. Kalichman, Picciano, & Roffman, 2008; Mustanski, Donenberg, & Emerson, 2006; Robertson, et al., 2006). Fisher and Fisher (1992) suggest the inconsistent findings for the association between information and behavior may be attributed to (a) methodological and/or (b) conceptual problems. First, information is likely to have a direct association with behavior when both are measured at the same level of specificity (e.g., condom information and use). In the current study, we assessed information using two general measures of HIV and STD information. To test whether information specific to condom use had a direct effect on behavioral skills or behavior, we reanalyzed the model using the three condom information items as a sole indicator of information but found the paths between information and (a) behavioral skills and (b) behavior remained similar to the original model; these analyses indicate that the negative association between information and behavioral skills and the null association of knowledge to condom use is unlikely due to measurement. Second, inconsistencies regarding the information component of the IMB model may be more conceptually problematic. Many researchers have suggested that information is an important but unnecessary precursor to HIV-risk prevention behavior, especially when that behavior is complicated (J. D. Fisher & Fisher, 1992).

Methodological and conceptual problems, as well as sample characteristics, may explain inconsistencies between information and behavioral skills. First, studies examining the IMB model typically use a proxy measure of behavioral skills such as self-efficacy. Research has shown confidence regarding condom use may not be indicative of actual condom skills (Langer, Zimmerman, & Cabral, 1994). Individual-level information regarding HIV-prevention methods may predict an individual's perceived ability to enact risk reducing behavior but may not predict an individual's ability to enact condom use skills in a sexual situation. In this study, we found that information was negatively related to enacted condom skills (e.g., refusing to have unprotected sex). Perhaps STD patients – who may have participated in counseling and testing but not skills training – exhibit high levels of HIV knowledge but cannot enact risk reduction behavior. Second, post-hoc analyses examining participant characteristics associated with information indicated that younger patients were more likely to respond correctly to the four types of HIV-information (ps < .01). Age-related differences in condom skills have also been found among substance abusers in treatment (S. Kalichman, et al., 2002). Finally, condom use (and condom skills) involves communication and negotiation with a partner; HIV-prevention information on the part of one partner may have less impact on dyadic behavior. Examining the IMB model at the dyadic level may elucidate the role of information in condom skills and behavior (Harman & Amico, 2008).

Consistent with the IMB model, condom-related motivation had a direct effect on both behavioral skills and condom use, whereas behavioral skills had a direct effect on condom use. Results suggest that STD clinic patients who are highly motivated are likely to acquire the requisite skills to enact HIV-preventative behavior. Likewise, motivation to engage in condom use predicted condom use behavior irrespective of behavioral skills. Multiple-groups analyses showed stronger associations between motivation and condom use among participants who had not been treated for a STD compared with those who had. Previous research has shown that STD repeaters often fail to return for posttest counseling (Hightow, et al., 2003; Hightow, et al., 2004; S. C. Kalichman & Cain, 2008). Testing positive for STDs, and receiving subsequent treatment, may be ineffective for increasing motivation and reducing sexual risk behavior because patients eschew counseling aimed at increasing motivation and providing skills training.

These findings suggest that interventions among STD clinic patients should focus on activities addressing condom use motivation and behavioral skills. Consistent with recommendations set forth by Fisher and Fisher (1992), elicitation research should be conducted to identify STD clinic patients’ motivation and behavioral skills deficits associated with condom use, and interventions should be developed targeting those deficits (Johnson, Carey, Chaudoir, & Reid, 2006). Because “STD repeaters” show less motivation for condom use, interventions for patients with a history of STD treatment should focus more on enhancing motivation for risk reduction followed by more intensive skill-based interventions. In contrast, interventions among patients who have not had prior STD treatment might focus on increasing specific behavioral skills.

Limitations

Several factors are important in interpreting these findings. First, we tested a theoretical model using SEM with specified paths, implying directionality among the constructs using cross-sectional data. Thus, direction of the effects cannot be determined from these data; longitudinal data are needed to study the effects of condom use over time. Second, this sample of adult STD clinic patients may not be representative of all STD clinic patients. Nonetheless, examining determinants of condom use among at-risk clinic patients is important given the health threats and disparities evident in low-income urban communities. Finally, data were gathered from self-reports, which are imperfect indicators of behavior. We minimized this problem by using ACASI, which are known to reduce under-reporting of sensitive information (Des Jarlais, et al., 1999; Newman, et al., 2002; Schroder, Carey, & Vanable, 2003).

CONCLUSIONS

The IMB model was used to examine determinants of condom use among STD clinic patients. Motivation and behavioral skills were the most important predictors of condom use. Multiple-group analyses indicated motivation was a significant predictor of condom use among patients who had not been treated for STDs compared to those who had been treated. Results suggest that sexual risk reduction interventions among STD clinic patients should include activities that enhance condom use motivation and strengthen skills to increase condom use.

Table 1.

Comparison of Path Coefficients for Participants Reporting Prior STD Treatment (n = 1124) or No Prior STD Treatment (n = 350).

| Reported No Previous STD Treatment | Reported Previous STD Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Information - Behavioral Skills | -0.31 | 0.12 | -0.17** | -0.49 | 0.09 | -0.24*** |

| Motivation - Behavioral Skills | 1.49 | 0.31 | 0.61*** | 1.06 | 0.16 | 0.50*** |

| Information - Behavior | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | -0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Motivation - Behavior | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.42** | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.11* |

| Behavioral Skills - Behavior | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.34*** | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.48*** |

p <.05

p <.01

p<.001.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH068171) to Michael P. Carey. We thank the participants, clinic nurses and staff, and our research team (Mary-Leah Albano, LuAnne Cori, Nicoy Douglas, Joyce Jones, Tracy Montesano, and Tricia Santa-Ferrara).

Author biographies

Lori A. J. Scott-Sheldon, PhD, is Research Assistant Professor in the Center for Health and Behavior at Syracuse University.

Michael P. Carey, PhD, is Dean's Professor of the Sciences and Director of the Center for Health and Behavior at Syracuse University.

Peter A. Vanable, PhD, is Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology at Syracuse University.

Theresa E. Senn, PhD, is Research Assistant Professor in the Center for Health and Behavior at Syracuse University.

Patricia Coury-Doniger, FNPC, is Clinical Associate in the School of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Rochester.

Marguerite A. Urban, MD, is Associate Professor of Medicine in the School of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Footnotes

To test whether information specific to condom use had a direct effect on behavioral skills or behavior, we reanalyzed the model using the three condom-specific information items as a sole indicator of information. Paths between information and behavioral skills (β = -.05, p =.11) or behavior (β = .01, p >.05) remained similar in direction and magnitude to the original model (fit indices of the revised model: CFI = .99; RMSEA = .04; χ2 [2] = 6.60, χ2/df = 3.30). We further analyzed patient characteristics (age, gender) to examine differences between those who responded correctly to each of the four information indicators and those who had incorrect responses. In these analyses, we found information deficits among older rather than younger patients, ps <.01. No gender differences were found, ps ≥ .18.

Compared to those who had never been treated, patients who had received STD treatment were more likely to be female, African-American, and older, and had a high school diploma or less, were unemployed, and had an annual income of less than $15,000, ps <.001. Patients who had prior treatment were less likely to report drinking prior to their last sexual occasion compared with those who had never been treated for STDs (26% vs. 35%), χ2 (1) = 9.96, p =.002. No other differences in sexual risk characteristics (e.g., number of sexual partners) were found, ps >.05.

REFERENCES

- Anderson ES, Wagstaff DA, Heckman TG, Winett RA, Roffman RA, Solomon LJ, et al. Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model: testing direct and mediated treatment effects on condom use among women in low-income housing. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(1):70–79. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 16.0 (Version 16.0) SPSS; Chicago: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brown IS. Development of a scale to measure attitude toward the condom as a method of birth control. Journal of Sex Research. 1984;20(3):255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AD, Fisher JD, Benziger TJ. Determinants of HIV risk among Indian truck drivers. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(11):1413–1426. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AD, Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Murray DM. Understanding condom use among heroin addicts in methadone maintenance using the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(4):451–471. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Braaten LS, Maisto SA, Gleason JR, Forsyth AD, Durant LE, et al. Using information, motivational enhancement, and skills training to reduce the risk of HIV infection for low-income urban women: a second randomized clinical trial. Health Psychology. 2000;19(1):3–11. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Schroder KE, Vanable PA. Reducing HIV-risk behavior among adults receiving outpatient psychiatric treatment: results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):252–268. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Maisto SA, Kalichman SC, Forsyth AD, Wright EM, Johnson BT. Enhancing motivation to reduce the risk of HIV infection for economically disadvantaged urban women. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(4):531–541. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Schroder KE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14:172–182. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.172.23902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Vanable PA, Senn TE, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA. Evaluating a two-step approach to sexual risk reduction in a publicly-funded STI clinic: rationale, design, and baseline data from the Health Improvement Project-Rochester (HIP-R). Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2008;29:569–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC The role of STD prevention and treatment in HIV prevention. 2007a Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/hiv/STDFact-STD&HIV.htm.

- CDC Trends in reportable sexually transmitted diseases in the United States, 2006. 2007b Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/trends2006.htm.

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LA. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. LEA; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Comer DM, Wiesenfeld HC, Chang CC, Tarter R, Lave JR, et al. Alcohol and drug use and related disorders: An underrecognized health issue among adolescents and young adults attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(9):565–570. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000206422.40319.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Paone D, Milliken J, Turner CF, Miller H, Gribble J, et al. Audio-computer interviewing to measure risk behaviour for HIV among injecting drug users: a quasi-randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1657–1661. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Shuper PA. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of HIV preventive behavior. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2009. pp. 21–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Williams SS, Malloy TE. Empirical tests of an information-motivation-behavioral skills model of AIDS-preventive behavior with gay men and heterosexual university students. Health Psychol. 1994;13(3):238–250. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WA, Williams SS, Fisher JD, Malloy TE. Understanding AIDS risk behavior among sexually active urban adolescents: An empirical test of the information--motivation--behavioral skills model. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3(1):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(3):286–299. [Google Scholar]

- Harman JJ, Amico KR. The Relationship-Oriented Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model: A Multilevel Structural Equation Model among Dyads. AIDS Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow LB, Miller WC, Leone PA, Wohl D, Smurzynski M, Kaplan AH. Failure to return for HIV posttest counseling in an STD clinic population. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(3):282–290. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.4.282.23826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow LB, Miller WC, Leone PA, Wohl DA, Smurzynski M, Kaplan AH. Predictors of repeat testing and HIV seroconversion in a sexually transmitted disease clinic population. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(8):455–459. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000135984.27593.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howards PP, Thomas JC, Earp JA. Do clinic-based STD data reflect community patterns? Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13(11):775–780. doi: 10.1258/095646202320753745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski BC, Carey MP. Development and psychometric evaluation of a self-administered questionnaire to measure knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases. AIDS & Behavior. 2007;11:557–574. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9168-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(5):642–650. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S, Stein JA, Malow R, Averhart C, Devieux J, Jennings T, et al. Predicting protected sexual behaviour using the Information-Motivation-Behaviour skills model among adolescent substance abusers in court-ordered treatment. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7(3):327–338. doi: 10.1080/13548500220139368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Cain D. Repeat HIV testing and HIV transmission risk behaviors among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15(2):127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Picciano JF, Roffman RA. Motivation to reduce HIV risk behaviors in the context of the Information, Motivation and Behavioral Skills (IMB) model of HIV prevention. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(5):680–689. doi: 10.1177/1359105307082456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. [July 21, 2009];Multiple group models. 2008 November 20; 2008. from http://davidakenny.net/cm/mgroups.htm.

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Langer LM, Zimmerman RS, Cabral RJ. Perceived versus actual condom skills among clients at sexually transmitted disease clinics. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(5):683–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichliter JS, Ellen JM, Gunn RA. STD repeaters: Implications for the individual and STD transmission in a population. In: Aral SO, Douglas JM, Lipshutz JA, editors. Behavioral interventions for prevention and control of sexually transmitted diseases. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 354–373. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Donenberg G, Emerson E. I can use a condom, i just don't: the importance of motivation to prevent HIV in adolescent seeking psychiatric care. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(6):753–762. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JC, Des Jarlais DC, Turner CF, Gribble J, Cooley P, Paone D. The differential effects of face-to-face and computer interview modes. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):294–297. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ, Harlow LL. Condom influence strategies in a community sample of ethnically diverse men and women. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004a;34:1730–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ, Harlow LL. Condom negotiation in heterosexually active men and women: Development and validation of a condom influence strategy questionnaire. Psychology and Health. 2004b;17:557–574. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AA, Stein JA, Baird-Thomas C. Gender differences in the prediction of condom use among incarcerated juvenile offenders: testing the Information-Motivation-Behavior Skills (IMB) model. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco WP, Levine B, Reed DL, Thompson K. Attitudes about condom use as an AIDS-relevant behavior: Their factor structure and relation to condom use. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;3(2):265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(2):104–123. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock HS, Sweeney S, Satten GA, Gwinn M. HIV seroincidence and risk factors among patients repeatedly tested for HIV attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States, 1991 to 1996. STD Clinic HIV Seroincidence Study Group. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Hum Retrovirol. 1998;19:506–512. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199812150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]