Abstract

This article examines the association between neighborhood characteristics at the census tract–level, couples’ perceived neighborhood social cohesion and informal social control, and male-to-female (MFPV) and female-to-male (FMPV) partner violence in the United States. Data come from a second wave of interviews (2000) with a national sample of couples 18 years of age and older who were first interviewed in 1995. The path analysis shows that poverty is associated with perceived social cohesion and perceived social control as hypothesized. However, there is no significant mediation effect for social control or social cohesion on any type of violence. In the path analysis, Black ethnicity is associated with social cohesion, which is associated with MFPV. Intimate partner violence (IPV), as a form of domestic violence, may not be as concentrated in high-poverty neighborhoods as criminal violence. IPV may be more determined by personal and dyadic characteristics than criminal violence.

Keywords: ethnicity, intimate partner violence (IPV), neighborhood characteristics, social cohesion, social control

Introduction

This article examines the association between neighborhood poverty and other socioeconomic indicators (unemployment, working class composition, and percentage high school graduation) at the census tract level, perceived social cohesion, perceived social control, and male-to-female (MFPV) and female-to-male (FMPV) partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. IPV is a major public health problem in the United States. Results from a 1985 national survey indicated that the 12-month rate of MFPV and FMPV were 11.6% and 12.4%, respectively (Straus & Gelles, 1990). Cross-sectional analyses of the 1995 baseline survey conducted as part of the study reported in this article showed that the rates of MFPV and FMPV among U.S. couples were 13.6% and 18.2%, respectively (Schafer, Caetano, & Clark, 1998).

Ethnicity is one of the many factors associated with involvement in IPV. Some of the available evidence indicates that rates of IPV are higher among Blacks and Hispanics than Whites. For instance, analysis of the 1975 National Family Violence Survey showed that Blacks reported annual rates of severe husband-to-wife violence twice that of other ethnic minorities, and 400% greater than the rate for Whites (Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980). Similarly, Cazenave and Straus (1990) in their analysis of the 1985 National Family Violence Resurvey found that Blacks had an annual incidence rate of severe husband-to-wife violence approximately 3.7 times higher than for Whites (11% vs. 3%). Straus and Smith (1990) found that among Hispanics, the annual rate of severe husband-to-wife violence was 7.3%, 2 times higher than the rate for Whites. Previous analysis of the data in this article showed 12-month rates of MFPV of 11% for Whites, 23% for Blacks, and 17% for Hispanics. Rates of FMPV were 15% among Whites, 30% among Blacks, and 21% among Hispanics. Longitudinal analyses showed that minority status is associated with a higher probability of recurrence (Blacks and Hispanics) and incidence (Hispanics) of IPV than White ethnicity (Caetano, Field, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2005).

Most epidemiological studies examining predictors of IPV have focused on individual-level risk factors. However, theories explaining IPV attribute violence to individual-level factors generating interpersonal conflict in the family (Sabol, Coulton, & Korbin, 2004) as well as to supra individual forces such as Garbarino’s (1977) ecological theory and Gelles’s (1985) socialstructural theory. The first theory sees child abuse as arising from tensions between family and the community. The second theory sees IPV as a response to “socially structured stress,” that is, stress associated with factors such as low income and unemployment. Some of the factors studied as predictors of IPV are personality characteristics, childhood history of abuse, history of violence between parents or guardians, substance abuse, income level, employment, and education. Impulsive personality characteristics or conduct disorders have also been associated with an increased risk of perpetration of IPV (Farrington & Loeber, 2000; Moffitt & Caspi, 1998). These factors do not act in isolation, and past research suggests that differences in rates of IPV between Whites and Hispanics have been explained by the combined effects of sociodemographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, drinking, and family history of violence (Caetano, Schafer, & Cunradi, 2001; Kantor, 1990, 1993).

Alcohol is another individual-level factor that also plays an important role in IPV. An overview of studies concerning IPV estimated that men are drinking at the time of the event in about 45% of cases (range across all studies is 6%-57%) and women are drinking in about 20% of such events (ranging from 10%-27%; Roizen, 1993). Another review concluded that the association between alcohol and violence is not trivial, with the largest associations being observed between chronic alcohol use and IPV (Lipsey, Wilson, Cohen, & Derzon, 1997). There is also evidence that alcohol is associated with more severe injuries and with greater chronicity of violence (Brecklin & Ullman,2002; Quigley & Leonard, 1999, 2000). Previous cross-sectional analysis of the 1995 baseline survey in the research reported here shows that from 27% to 41% of the men and from 4% to 24% of the women, depending on ethnicity, were drinking at the time of the violent incident (Caetano, Cunradi, Clark, & Schafer, 2000). Alcohol-related problems among women in the community have been identified as a significant predictor of MFPV among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics; alcohol-related problems among men predicted IPV only among Blacks (Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 2000). Alcohol-related dependence indicators (e.g., withdrawal symptoms and alcohol tolerance), as compared to alcohol-related social problems (e.g., loss of job and legal problems), seem to be particularly strong predictors of IPV among Blacks, independent of who in the couple reports the problems (Caetano, Nelson, & Cunradi, 2001).

Neighborhood-level indicators of socioeconomic disadvantage, usually with census tracts as the unit of analysis, have been consistently associated with a variety of health problems such as having a low birth weight infant (O’Campo, Xue, Wang, & Caughy, 1997), alcohol-related problems among Black men (Jones-Webb, Snowden, Herd, Short, & Hannan, 1997), depression (Yen & Kaplan, 1999), prevalence of coronary heart disease and coronary risk factors (Diez-Roux et al., 1997), and all-cause mortality (Anderson, Sorlie, Backlund, Johnson, & Kaplan, 1996; Haan, Kaplan, & Camacho, 1987). Occasionally, neighborhood characteristics have been associated with positive health outcomes. High-density Mexican American neighborhoods seem to have a protective effect against strokes, cancer, and hip fracture that outweigh the bad effects associated with poverty in these same neighborhoods (Eschbach, Ostir, Patel, Markides, & Goodwin, 2004).

With regard to IPV, results of neighborhood-level research are somewhat inconsistent (Sabol et al., 2004). Median rates of police reports of IPV were 9 times higher in concentrated poverty tracts than in nonpoverty tracts in Duval County, Florida (Miles-Doan & Kelly, 1997). Similarly, women residing in census tracts in the lowest quartile of per capita income in Baltimore, Maryland, were 4 times more likely to self-report IPV than women residing in census tracts in the highest quartile of per capita income (O’Campo et al., 1995). An association of similar magnitude was found for women residing in census tracts characterized by high versus low unemployment rates. In a national study of couples, Black couples living in impoverished neighborhoods were at higher risk for MFPV and FMPV than Black couples in less socially disadvantaged ones; White couples in impoverished neighborhoods were at a higher risk for self-reported FMPV only (Cunradi et al., 2000). Rennison and Welchans (2000), using the National Crime Victimization Survey, also found differences in self-reported IPV rates between poor inner city areas and suburban neighborhoods. Sabol et al. (2004), using findings from Lynch and Weirsema (2001), suggest that IPV and other forms of domestic violence may not be concentrated in high-poverty neighborhoods as criminal violence. In this article, neighborhood-level characteristics are represented with U.S. Census data (tract level) on education, income, employment, and working-class composition.

An excellent example of the association between neighborhood characteristics and criminal violence is the work of Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls (1997). These authors reported a positive association between delinquency and collective efficacy. This is a concept representing the ability that residents of particular neighborhoods have to act in a socially cohesive way and implement informal social controls that lead to the maintenance of public order and thus minimize crime. Perceived social cohesion and perceived informal social control are two closely related constructs that are seen as dimensions of collective efficacy (Sampson et al., 1997). The available evidence indicates that neighborhoods high in collective efficacy have lower rates of perceived violence and lower rates of violent victimization and homicide (Sampson et al., 1997). Collective efficacy appears to act as a mediator between criminal violence and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, minimizing problems such as delinquency (Sampson, 2000), children’s mental health problems (Xue, Leventhal, Brooks-Gunn, & Earls, 2005), and delaying sexual activity onset among Black youth (Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004).

In this article, we apply Sampson et al.’s (1997) concept of social control and social cohesion in combination with neighborhood characteristics obtained from U.S. Census 2000 data at the tract level to further understanding of predictors of IPV. Social control and social cohesion are scales that measure respondents’ perception of neighborhood characteristics. Other factors also considered include traditional predictors of IPV: age, ethnicity, annual household income level, alcohol consumption, and binge drinking, all individual-level variables. Neighborhood characteristics obtained at the census tract level include the proportion of the population (25 years and older) with a high school diploma, the proportion of the population in working-class occupations, the proportion unemployed, and the proportion below the federal poverty guideline.

The basic theoretical framework guiding this analysis is provided by Sampson et al.’s (1997) associations between social cohesion and social control. Gelles’s (1985) social-structural theory is also considered. Although Sampson et al.’s original research does not include IPV, it seems feasible to propose that in neighborhoods characterized by poverty, low social cohesion and low social control, and stresses associated with these, plus individual-level conditions, will affect family relationships and lead to IPV. In other words, neighborhoods characterized by social disorganization may also lack norms and social controls that limit aggressive behavior and conflict resolution through aggression. These neighborhoods would have not only high rates of crime but potentially high rates of IPV as well. The crime-related violence that is present in the community and the lack of social controls would affect intimate relationships characterized by high levels of stress and create conditions conducive to the development of IPV. These relationships are best represented by a mediational model, similar to that reported by Sampson et al., in which social cohesion and social control mediate the effect of poverty on IPV. Direct paths between predictor variables such as ethnicity and IPV may also exist. There are important theoretical and practical reasons for testing these associations between neighborhood-level variables and IPV. Theoretically, it is important to assess the extent to which characteristics of the social environment influence personal behavior, especially violence. Understanding the special nature of the base for specific behaviors will help us further understand human behavior in general. This is also of practical importance because it may provide the base for the development of new and perhaps more effective prevention intervention to minimize IPV in communities. For instance, community interventions aimed at increasing community-based activities, or reactivating or developing community-based organizations, may lead to increased sense of social cohesion and social control, changing individuals’ perceptions of their neighborhood and reducing violence levels.

Method

Sample

Participants in this study constitute a multistage random probability sample representative of married and cohabiting couples in the 48 contiguous United States. These participants were interviewed as part of a second wave of data collection in a longitudinal study of IPV, with the first interview conducted in 1995. The sample analyzed herein is the second wave of interviews because the first wave did not collect information on perceived social cohesion and perceived informal social control. At the time of the first interview, all couples 18 years of age and older living in randomly selected households were eligible to participate. This process identified 1,925 couples, of which 1,635 couples completed the interview for a response rate of 85%. Included in the sample were oversamples of Black and Hispanic couples. In 2000, the 1,635 couples previously interviewed were contacted again to participate in the 5-year follow-up. At follow-up, both members of 15 couples were either dead or incapacitated, leaving 1,620 couples (1,635 – 15) to be reinterviewed. Interviews were successfully completed with 1,392 couples, or 72% of the 1925 couples from the original 1995 eligible sample (or 85% of the couples actually interviewed in 1995). Among these couples, 1,136 were considered intact (still either married or living together with the same partner) and are the focus of the analysis. The final analyses include Black (n = 232), Hispanic (n = 387), and White (n = 406) intact couples with homogeneous ethnicity.

Nonresponse Analysis

Because the sample under analysis was interviewed twice, in 1995 and 2000, there are 1995 data on 2000 nonrespondents. This made it possible to conduct an analysis of nonrespondents’ characteristics in 2000. Results from this analysis indicated that men who were under age 30, or unemployed, and women who were in the 40 to 49 age group, or who did not report being victimized by violence during their childhood, were more likely than others to be lost to follow-up. Ethnicity, education, income, marital status, alcohol consumption, drinking problems, history of observation of violence between parents, MFPV, and FMPV were investigated and not found to be related to nonresponse. Details of the nonresponse analysis are described elsewhere (Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2003).

Data Collection

All participants signed a written informed consent before being interviewed. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in respondents’ homes with standardized questionnaires in their preferred language (English or Spanish). Members of the couple were always interviewed independently. Interviews in which this independence appeared to be compromised were discarded (n = 20).

Measurements

Intimate Partner Violence

Both in 1995 and 2000, participants were asked about the occurrence of 11 violent behaviors that they may have perpetrated against their partners, or that their partners may have perpetrated against them, during the past year. The violence items were adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scale, Form R (Straus, 1990) and included the following: threw something; pushed, grabbed, or shoved; slapped; kicked, bit, or hit; hit or tried to hit with something; beat up; choked; burned or scalded; forced sex; threatened with a knife or gun; used a knife or gun. Due to survey time constraints, no frequency data were collected. MFPV was considered present when the male partner indicated perpetration of violence or the female partner indicated victimization by her partner. The reverse is true for FMPV. IPV variables were treated as continuous variables in the model (0 = none, 1 = any one type of act of violence, 2 = two or more types of acts).

Neighborhood-Level Variables

Census-based socioeconomic variables

Data obtained from the 2000 Census (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000) were linked to each couple’s geocoded record to describe census tract–level socioeconomic characteristics. Following Krieger’s (1992) census-based methodology, we defined education as the percentage of the population aged 25 years and older with a high school diploma; unemployment as the percentage of the population aged 16 years and older who were in the labor force but reported being unemployed; working-class composition as the percentage of the population aged 16 years and older who were classified as being in working-class occupations (e.g., construction laborers, machine operators, farming/fishing, rail/water other transportation, office administrative) as specified by the U.S. Department of Commerce; and poverty as the percentage of the tract’s population below the poverty line (US$12,700 annual income for a family of four; U.S. Census Bureau, 2007).

Perceived social cohesion

This measure replicated Sampson et al.’s (1997). Participants were asked about their level of agreement measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) with the following five statements about their neighborhood: people are willing to help their neighbors; this is a close-knit neighborhood; people can be trusted; people generally don’t get along; people do not share the same values. Internal consistency reliability for the scale is .83.

Perceived informal social control

This measure also replicated Sampson et al.’s (1997). Participants were asked about how likely it would be for people in their neighborhood to intervene, with likelihood measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale (very likely to very unlikely), if they were faced with the following situations: children were skipping school; children were spray painting graffiti on a local building; children were showing disrespect for an adult; if there was a fight and someone was being beaten or threatened; a fire station was being closed down by the city. Internal consistency reliability for the scale is .83.

Because both partners reported on the same neighborhood, we used the average of the two partners’ reports as measures of perceived social cohesion and social control. The correlation coefficient (weighted) between the partners’ reports for social cohesion is .43 and for social control is .39.

Average Alcohol Consumption per Week

The respondent’s frequency of drinking over the 12-month period prior to the survey was coded into 11 categories ranging from never to three or more times a day. Quantity of consumption was assessed by asking for the proportion of drinking occasions on which the respondent drank 5 or 6, 3 or 4, and 1 or 2 glasses each of wine, beer, and liquor was combined and used to estimate the average number of drinks of alcohol consumed weekly. A drink was defined as 1.5-ounces of spirits, a 4-ounce glass of wine or a 12-ounce can of beer, each of which contains approximately 12 grams of absolute alcohol. See Dawson and Room (2000) and Room (2000) for a discussion of the history of these survey measures.

Binge Drinking (Five or More Drinks on Occasion)

The information on drinking wine, beer, and liquor was also coded to identify the frequency of drinking occasions in which respondents drank five or more drinks in the past 12 months. Respondents were grouped into four categories: no occasions/ abstainers; less than once a month; 1-3 times a month; 4 or more times a month.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Ethnic identification

Respondents who identified themselves as “black of Hispanic origin (Latino, Mexican, Central or South American, or any other Hispanic origin)” and “white of Hispanic origin (Latino, Mexican, Central or South American, or any other Hispanic origin)” were classified as Hispanic. Respondents who selected the category “black, not of Hispanic origin” were classified as Black. Respondents who selected “white, not of Hispanic origin” were classified as White. The labels being used in this variable are a mixture of race (e.g., Black and White) and ethnicity (e.g., Hispanic), but the variable is understood as representing ethnicity as a social construct. The variable representing ethnicity was entered in the model as two dummy variables (Black vs. White; Hispanic vs. White), with White being the reference group. Thus, the path model identifies only Black and Hispanic ethnicity.

Age

The age of respondents was measured continuously in years as the age of the male and the age of the female in the couple.

Income

This is the total annual household income reported by the primary respondent selected for interview in the household. This selection followed random procedures, and once a respondent was selected and interviewed, the spouse or partner of that respondent was interviewed as well. In cases where the income information was missing for the primary respondent, then income was based on the information provided by the spouse or partner. The correlation between income information for those couples where both provided that information was .92. The categories used for total 1999 pretax household income were (a) US$4,000 or less, (b) US$4,001 to US$6,000, (c) US$6,001 to US$8,000, (d) US$8,001 to US$10,000, (e) US$10,001 to US$15,000, (f) US$15,001 to US$20,000, (g) US$20,001 to US$30,000, (h) US$30,001 to US$40,000, (i) US$40,001 to US$60,000, (j) US$60,001 to US$80,000, (k) US$80,001 to US$100,000, and (l) more than US$100,000. Household income was then used as a continuous variable, with income expressed in thousands of dollars.

Data Analysis

The correlational analyses reported in Table 1 were conducted using SPSS Software (version 16.0), using weights to correct for probability of selection into the sample and nonresponse rates, and further revised by poststratification to adjust the sample to known population distributions on certain demographic variables (ethnicity of the household informant, metropolitan status, and region of the country).

Table 1.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients Between Variables in Path Model §

| Male | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 1. Age | - | |||||||||||||

| 2. Alcohol volume | −.152** | - | ||||||||||||

| 3. Drinks 5+ at least once/yr | −.243** | .692** | - | |||||||||||

| 4. Black | −.011 | −.008 | −.084** | - | ||||||||||

| 5. Hispanic | −.203** | −.011 | .185** | −.422** | - | |||||||||

| 6. Income mid-point | −.094** | .156** | −.012 | −.003 | −.346** | - | ||||||||

| 7. Social cohesion | .120** | −.014 | −.078* | −.059 | −.131** | .205** | - | |||||||

| 8. Social control | −.020 | .085** | .016 | .041 | −.177** | .249** | .433** | - | ||||||

| 9. % H.S. grad | .066* | −.090** | −.114** | .014 | −.504** | .481** | .189** | .261** | - | |||||

| 10. % Unemployed | −.072* | −.104** | .017 | .138** | .370** | −.412** | −.166** | −.237** | −.726** | - | ||||

| 11.% Working class | −.095** | −.051** | −.135** | .000 | .281** | −.400** | −.150** | −.161** | −.739** | .433** | - | |||

| 12. % Below poverty level | −.036 | −.101** | .034 | .157** | .340** | −.417** | −.214** | −.298** | −.789** | .825** | .486** | - | ||

| 13. FMPV | −.266** | .140** | .146** | .088** | .059 | −.067* | −.084* | −.027 | −.064* | .056 | .065* | .086** | - | |

| 14. MFPV | −.232** | .150** | .183** | .092** | .082* | −.078* | −.144** | −.053 | −.119** | .116** | .087** | .148** | .735** | - |

| Female | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 1. Age | - | |||||||||||||

| 2. Alcohol volume | −.049 | - | ||||||||||||

| 3. Drinks 4+ at least once/yr | −.133** | .514** | - | |||||||||||

| 4. Black | −.017 | .033 | −.030 | - | ||||||||||

| 5. Hispanic | −.207** | −.195** | .025 | −.422** | - | |||||||||

| 6. Income mid-point | −.069* | .304** | .103** | −.003 | −.346** | - | ||||||||

| 7. Social cohesion | .135** | −.019 | .001 | −.059 | −.131** | .205** | - | |||||||

| 8. Social control | .012 | .073* | .041 | .041 | −.177** | .249** | .433** | - | ||||||

| 9. % H.S. grad | .083** | .235** | .042 | .014 | −.504** | .481** | .189** | .261** | - | |||||

| 10. % Unemployed | −.115** | −.155** | −.023 | .138** | .370** | −.412** | −.166** | −.237** | −.726** | - | ||||

| 11.% Working class | −.098** | −.169** | −.166** | .000 | .281** | −.400** | −.150** | −.161** | −.739 | .433** | - | |||

| 12. % Below poverty level | −.074* | −.179** | −.047 | .157** | .340** | −.417** | −.214** | −.298** | −.789** | .825** | .486** | - | ||

| 13. FMPV | −.262** | .062 | .052 | .088** | .059 | −.067* | −.084* | −.027 | −.064* | .056 | .065* | .086** | - | |

| 14. MFPV | −.222** | .045 | .016 | .092** | .082* | −.078* | −.144** | −.053 | −.119** | .116** | .087** | .148** | .735** | - |

Weighted

significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Note: Variables 1,2,3 are individual level

The analysis of the relationships between ethnicity, IPV, social cohesion, and social control used correlation and path analysis. Models were specified and estimated with the Mplus program, Version 5.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). This software is advantageous for several reasons: first, it allows for analyses in which exogenous variables may be either categorical (ethnicity) or continuous (age, income, alcohol volume, and binge drinking) and endogenous variables may be dichotomous (male-to-female partner violence, female-to-male partner violence) or continuous (social cohesion, social control). In addition, it allows analyses accounting for complex sampling and two-level analysis of the couple-level and census tract data. All endogenous variables were regressed on background variables (age, income, and education) and alcohol use variables (volume and binge drinking). In other words, the effect of neighborhood variables on MFPV and FMPV is examined while controlling for the effect of the individual-level variables described above. These variables are controlled because evidence indicates that they are independent predictors of IPV (Caetano, McGrath, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Field, 2005; Caetano, Nelson, et al., 2001; Cunradi, Caetano, & Schafer, 2002). Model development included the use of modification indices and evaluation of model fit. The fit of models was determined by examining consistency across multiple descriptive fit indexes. Hu and Bentler and others (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Loehlin, 2004; Muthén & Muthén, 1998) have suggested that the following goodness-of-model-fit statistics and the associated values support a good fit: Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > .95), comparative fit index (CFI >.95), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .06). Similarly, a good fit is supported for the weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) index for values ≤ 1.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). The data were also weighted to address differences in initial selection probabilities prior to parameter and model estimation, with the total weighted N equal to the actual number of respondents (to avoid biasing significance tests of coefficients by weights > 1). As stated in the results section, the model ultimately chosen is a saturated model.

Results

Correlations representing the bivariate associations between all variables in the path model (Figure 1) are presented in Table 1. The only correlations that vary between males and females are those involving age, alcohol volume, and binge drinking. This is because these are correlations between variables whose values vary across members of the couple. Correlations between age and MFPV and FMPV are statistically significant for both men and women, and of moderate magnitude. Individuals in younger age groups are more likely to report involvement in IPV than those in older age groups. Correlations between MFPV and FMPV and the drinking variables are of moderate magnitude for men and statistically significant. Among women, these correlations are of small magnitude, varying from .016 to .062, and not significant. Regarding income, correlations with MFPV and FMPV are not only negative and statistically significant but also of small magnitude, both below .10. Correlations between Black ethnicity and MFPV and FMPV are statistically significant but low in magnitude (below .10). The same happens for Hispanic ethnicity although in this case only the correlation with MFPV is significant.

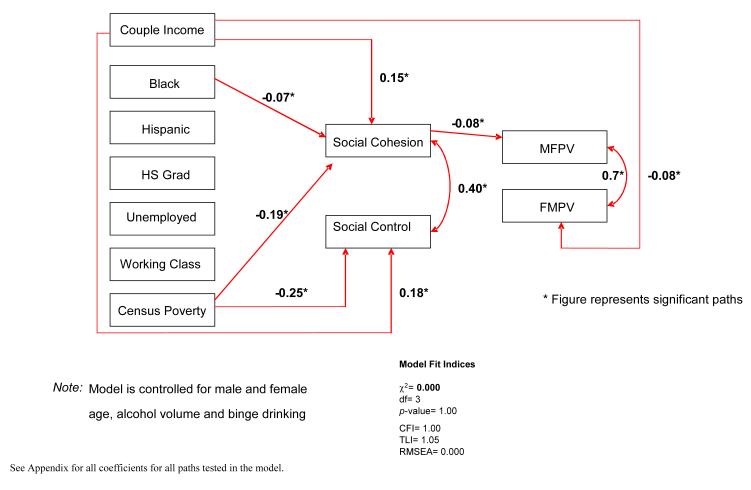

Figure 1.

Model representing the relationship between ethnicity,census variables and partner violence* (N=919)

The correlations between social cohesion and MFPV and FMPV are negative and small in magnitude but significant. The correlations for social control are not significant. With regard to census variables, the correlations with MFPV and FMPV vary in magnitude between .056 and .148. These correlations are all statistically significant, with the exception of that between unemployment and FMPV. These correlations are also slightly higher in magnitude for MFPV than for FMPV, and they are negative between education and the outcome variables. That is, the lower the proportion of high school graduates in the neighborhood, the higher the prevalence of violence between partners. Also, the higher the proportion unemployed, the proportion working class, or the proportion below the poverty level, the higher the prevalence of IPV.

The path models including correlations between error terms were considered. These correlations were .40, between social cohesion and social control, and .70, between MFPV and FMPV. The conceptual distinction between MFPV and FMPV is important although it is well known that they are highly correlated, and it is highly plausible that this correlation is a result both of common antecedents and of the dynamics of interaction within couples. For similar reasons, it is expected that the components of these variables not explained by our model should also be correlated. Similarly, social cohesion and social control are conceptually distinct neighborhood properties although ones with many common antecedents.

The model in Figure 1 shows a statistically significant path (negative) between Black ethnicity and social cohesion and between social cohesion and MFPV. However, the overall path from Black ethnicity to MFPV through social cohesion is not significant (p = .257), which indicates lack of evidence for mediation by social cohesion. Other significant paths indicate inverse relationships between poverty and social cohesion and social control.

In addition, there were also significant paths between income and social cohesion (b = 0.15), income and social control (b = 0.18), and income and FMPV (b = −0.08). Male age was associated with MFPV (b = −0.22) and with FMPV (b = −0.19). Finally, female volume of alcohol consumption was related to social cohesion (b = −0.10). Significant residual correlations exist between social control and social cohesion, and FMPV and MFPV. We have provided path coefficients for all paths tested in the final model (see Appendix). The model is equivalent to the nonrecursive model with all possible coefficients and is therefore just-identified (saturated). Hence, the chi-square for goodness of fit is equal to zero and the fit indices indicate perfect fit of the model to the observed correlations (c2 = 0.00, df = 3; p = 1.00; CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.05, RMSEA = 0.00; Kline, 2005).

Discussion

Although neighborhood poverty was significantly correlated with IPV, neither the direct path nor the total indirect path via perceived social cohesion and perceived social control was significant. The results do not confirm the hypothesis that perceived social cohesion and perceived social control mediate the effect of poverty on IPV. Poverty is related to perceived social cohesion and perceived social control as hypothesized. Thus, as Sabol et al. (2004) suggested, IPV, as a form of domestic violence, may not be as concentrated in high poverty neighborhoods as criminal violence is. IPV, as shown by previous research (Caetano, Schafer, et al., 2001; Cunradi et al., 2000), would be more determined by personal and dyadic characteristics than criminal violence.

One of the personal characteristics associated with both FMPV and MFPV in Table 1 is Black ethnicity. However, once the effect of sociodemographic and neighborhood variables is controlled for in the path model, the association between Black ethnicity and FMPV and MFPV seen in Table 1 becomes nonsignificant. This is different from previous analyses of this data set conducted with the 1995 baseline survey. Those analyses reported a direct association of Black ethnicity with FMPV only (Cunradi et al., 2000). It is possible that this result is different because the present analysis employs the 2000 follow-up to the 1995 baseline survey. Longitudinal analysis showed that FMPV in 1995 predicted couple separation in 2000 (Ramisetty-Mikler & Caetano, 2005). Thus, the 2000 data set analyzed here, comprising only intact couples, has perforce fewer FMPV cases than MFPV. It is also possible that the association between Black ethnicity and FMPV is not significant in the present analysis because of the specific set of variables whose effect is being controlled for in the path model. This set of variables is different from those in the analysis by Cunradi et al. (2000).

The finding that social control has a small and nonsignificant effect on IPV (low zero-order correlations −.027 for FMPV and −.053 for MFPV as well as nonsignificant path coefficients), in contrast to social cohesion, is intriguing. Effects of social control on IPV have not been explored so far. The measure of perceived social control, as described in the Method section, is constituted by five different items assessing problematic situations, none of which is related to IPV. Altogether, these items probably more accurately represent social control that influences behavior occurring outside the home, in public places. This may be the reason why this measure has no relationship with MFPV or FMPV in this sample.

Also, the measures of social control and social cohesion are based on respondents’ self-report and as such may not accurately represent the levels of control and cohesion that actually characterize the neighborhood. Debate about the usefulness of these measures has led to the development of more complex, multidimensional measures of neighborhood characteristics (e.g., Mujahid, Diez Roux, Morenoff, & Raghunathan, 2007), some of which are not based exclusively on self-reports but use observable indicators of neighborhood disorganization (Caughy, O’Campo, & Patterson, 2001; Furr-Holden et al., 2008; Pikora et al., 2002). In these latter cases, trained observers walk through neighborhood streets and count factors such as number of broken windows, abandoned houses, vacant lots, homeless individuals, number of adults and children on the street, and other factors.

Couples’ income has moderate and positive associations with social cohesion and social control and a small negative association with FMPV. So, compared to couples with higher income, couples with lower income reported perceptions of their neighborhoods as less cohesive and low in social control. This is basically the same relationship that the census-based indicator of poverty has with cohesion and control. The path analysis shows that income remains independently associated with FMPV, once the effect of other variables is controlled for in the analysis. The association of income and MFPV seen in Table 1 is no longer significant when the effect of the other variables in the path model is controlled for. The association between income and IPV has been reported before in the literature (Caetano, Schafer, et al., 2001; Cunradi et al., 2002). Gelles and Straus (1979) suggest that societal inequalities along socioeconomic position create stress and may lead to an increased likelihood of violence. In addition, individuals from lower socioeconomic strata may have more exposure to known predictors of IPV such as childhood physical abuse, substance abuse and dependence, depression, and poorer coping mechanisms (Cunradi et al., 2002).

Altogether, the findings reported herein indicate little evidence that perceived neighborhood characteristics such as social cohesion and social control are associated with MFPV and FMPV. IPV tends to occur inside homes, hidden from the public eye. Even when neighbors know about the occurrence of IPV, the tendency is not to interfere with such matters that are often seen as private. IPV is different from delinquency and crime, which may affect communities at a more macro level, and thus are associated with community characteristics such as social cohesion and social control.

Finally, the set of neighborhood-level indicators included in the analysis is limited to educational level, unemployment level, working class composition, and poverty. Other census-based indicators exist (e.g., proportion of residents who are ethnic minorities, proportion of homes which are owner occupied) that could perhaps provide a more accurate representation of neighborhood characteristics and be associated with IPV. Our choice of mainly socioeconomic indicators was based on previous research linking social and economic inequalities to IPV (Gelles & Straus, 1979). Also, census-based data at the tract level may not map well onto local residents’ perceptions of what constitutes a residential neighborhood. Although census tracts by definition have relatively homogeneous demographic characteristics, they can be larger than a “neighborhood”, with populations that vary from 2,500 to 8,000 residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2005).

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. Couples were selected at random from the household population in the continental United States. Information on IPV was collected from both partners, thus enhancing the probability of identification of spousal violence (Stets & Straus, 1990; Szinovacz & Egley, 1995). Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish, allowing for the selection of respondents who were not English speakers. The design also had limitations. The data under analysis are cross-sectional in nature, and do not allow for considerations of time order as well as for the control of past behavior on present behavior. Data were collected for the 12 months prior to the survey. Another limitation of the study is that 15% of the eligible couples at baseline refused to participate. In 2000, the proportion of originally eligible couples not interviewed was 28%. Selection biases may be present if in 1995 or 2000 nonparticipating couples were more likely to have experienced IPV. This may bias results given that couples who separated because of IPV are not included.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Work on this paper was supported by a grant (R37-AA10908) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to the University of Texas School of Public Health.

Footnotes

Note The final, definitive version of the article is available at http://online.sagepub.com/.

References

- Anderson RT, Sorlie P, Backlund E, Johnson N, Kaplan GA. Mortality effects of community socioeconomic status. Epidemiology. 1996;8(1):42–47. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecklin LR, Ullman SE. The roles of victim and offender alcohol use in sexual assaults: Results from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(1):57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography. 2004;41:697–720. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Clark CL, Schafer J. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the US. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11(2):123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field CA, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. The five-year course of intimate partner violence among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:1039–1057. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, McGrath C, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Field CA. Drinking, alcohol problems and the five-year recurrence and incidence of male to female and female to male partner violence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(1):98–106. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150015.84381.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Nelson S, Cunradi CB. Intimate partner violence, dependence symptoms and social consequences from drinking among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. American Journal on Addictions. 2001;10(Suppl. 1):60–69. doi: 10.1080/10550490150504146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. Characteristics of nonrespondents in a US national longitudinal survey on drinking and intimate partner violence. Addiction. 2003;98:791–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Cunradi CB. Alcohol-related intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Research & Health. 2001;25(1):58–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MO, O’Campo PJ, Patterson J. A brief observational measure for urban neighborhoods. Health & Place. 2001;7:225–236. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(01)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazenave NA, Straus MA. Race, class, network embeddedness, and family violence: a search for potent support systems. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. Transaction Publishers; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. pp. 321–339. [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark CL, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: A multilevel analysis. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Socioeconomic predictors of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17:377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Room R. Towards agreement on ways to measure and report drinking patterns and alcohol-related problems in adult general population surveys: The Skarpo conference overview. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12(1-2):1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Roux AV, Javier NF, Muntaner C, Tyroler HA, Comstock GW, Shahar E, et al. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146:48–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschbach K, Ostir GV, Patel KV, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Neighborhood context and mortality among older Mexican Americans: Is there a barrio advantage? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1807–1812. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Loeber R. Epidemiology of juvenile violence. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;9:733–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden CD, Smart MJ, Pokorni JL, Ialongo NS, Leaf PJ, Holder HD, et al. The NIfETy method for environmental assessment of neighborhood level indicators of violence, alcohol, and other drug exposure. Prevention Science. 2008;9:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J. Human ecology of child maltreatment—A conceptual model for research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1977;39:721–735. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ. Family violence. Annual Review of Sociology. 1985;11:347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ, Straus MA. Determinants of violence in the family: Towards a theoretical integration. In: Burr W, Hill R, Nye F, Reiss I, editors. Contemporary theories about the family. Free Press; New York: 1979. pp. 549–581. [Google Scholar]

- Haan M, Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Poverty and health: Prospective evidence from the Alameda County Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;125:989–998. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, Snowden L, Herd D, Short B, Hannan P. Alcohol-related problems among Black, Hispanic, and White men: The contribution of neighborhood poverty. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:539–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK. Ethnicity, drinking, and family violence. Paper presented at the American Society of Criminology Meetings, Meetings; Baltimore, MD. Nov, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: Refining the brushstrokes in portraits of alcohol and wife assaults. 1993 (Research monograph No. 24, NIH Publication No. 93-3496)

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: Validation and application of a census-based methodology. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:703–710. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB, Cohen MA, Derzon JH. Is there a causal relationship between alcohol use and violence? A synthesis of evidence. In: Galanter M, editor. Alcohol and violence: Epidemiology, neurobiology, psychology, family issues. Vol. 13, Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Plenum Press; New York: 1997. pp. 245–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent variable models: An introduction to factor, path, and structural equation analysis. 4th ed Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP, Weirsema B. 2000 Proceedings of the section on government statistics and section on social statistics. American Statistical Association; Alexandria, VA: Mar, 2001. The role of individual, household, and areal characteristics in domestic violence. [Google Scholar]

- Miles-Doan R, Kelly S. Geographic concentration of violence between intimate partners. Public Health Reports. 1997;112(2):135–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Annotation: Implications of violence between intimate partners for child psychologists and psychiatrists. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39(2):137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD, Raghunathan T. Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: From psychometrics to ecometrics. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165:858–867. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus users guide. Author; Los Angeles: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus. Version 5.0 Author; Los Angeles: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Campo P, Gielen AC, Faden RR, Xue X, Kass N, Wang MC. Violence by male partners against women during the childbearing year: A contextual analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:1092–1097. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Campo P, Xue X, Wang MC, Caughy MO. Neighborhood risk factors for low birthweight in Baltimore: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1113–1118. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikora TJ, Bull FC, Jamrozik K, Knuiman M, Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. Developing a reliable audit instrument to measure the physical environment for physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Husband alcohol expectancies, drinking, and marital-conflict styles as predictors of severe marital violence among newlywed couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13(1):49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Alcohol and the continuation of early marital aggression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1003–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence as predictors of separation among U.S. couples: A longitudinal model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:205–212. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennison CM, Welchans S. U.S. Department of Justice; Washington, DC: Intimate partner violence. 2000 (Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report No. NCJ 178247)

- Roizen J. Issues in the epidemiology of alcohol and violence. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1993. (Research Monograph No. 24, NIH Publication No. 93-3496) [Google Scholar]

- Room R. Measuring drinking patterns: The experience of the last half century. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabol WJ, Coulton CJ, Korbin JE. Building community capacity for violence prevention. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:322–340. doi: 10.1177/0886260503261155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. A neighborhood-level perspective on social change and the social control of adolescent delinquency. In: L C, R S, editors. Negotiating adolescence in times of social change. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Caetano R, Clark CL. Rates of intimate partner violence in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1702–1704. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE, Straus MA. Gender differences in reporting marital violence and its medical and psychological consequences. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. pp. 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles R. How violent are American families? Estimates from the National Family Violence Resurvey and other studies. In: Straus M, Gelles R, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ, Steinmetz SK. Behind closed doors: Violencein the American family. Doubleday/Anchor; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Smith C. Violence in Hispanic families in the United States: Incidence rates and structural interpretations. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. Transaction Books; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. pp. 341–367. [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz ME, Egley LC. Comparing one-partner and couple data on sensitive marital behaviors: The case of marital violence. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:995–1010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics, and Statistics; Washington, DC: Summary tape file 3. 2000

- U.S. Census Bureau [Retrieved November 17, 2009];Geographic Areas Reference Manual, Chapter 10: Census tracts and block numbering areas. 2005 September 16; from http://www.census.gov/geo/www/garm.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau [Retrieved January 28, 2008];Poverty thresholds 2006. 2007 August 28; from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/threshld/thresh06.html.

- Xue YG, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J, Earls FJ. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:554–563. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen IH, Kaplan GA. Poverty area residence and changes in depression and perceived health status: Evidence form the Alameda County Study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;28(1):90–94. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.