Abstract

Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix is a rare neoplasm with poor prognosis. It may be misdiagnosed especially when amelanotic, in which case immunohistochemistry is useful in reaching the diagnosis. We present one such case of a 65-year-old postmenopausal female patient presenting with bleeding per vaginum. Speculum examination revealed an ulcero-proliferative growth involving the cervix. On histopathological examination it was originally suspected to be a poorly differentiated carcinoma or a non-epithelial malignant tumor, but was subsequently correctly diagnosed by immunohistochemical staining with the HMB-45 antibody and S-100 protein.

Keywords: Aamelanotic melanoma, HMB-45 antibody

INTRODUCTION

Malignant melanoma, which is a common neoplasm of the skin and mucous membranes, makes up 1% of all cancer cases. Approximately 3% to 7% of malignant melanomas in women develop within genital tract. The vast majority of these cases occur in vulva and vagina. Primary melanoma of the uterine cervix is extremely rare, accounting for only 3% to 9% of gynecological melanomas, and it is 5 times less common than primary melanoma of vagina and vulva.1 Till now about 50 cases of primary malignant melanoma of the cervix have been reported in the literature and among these 8 cases were of amelanotic type. The absence or rarity of melanin granules in amelanotic melanomas can lead to their misdiagnoses as carcinomas, sarcomas or lymphoma.2-9 In this context, ancillary immunohistochemistry is of value and the use of vimentin, S-100 and HMB-45 monoclonal antibody is reported to vastly improve the accuracy of diagnosing malignant melanomas.3-9 We present a rare case of primary amelanotic melanoma of the cervix, which was initially suspected to be a poorly differentiated malignant tumor with a wide differential diagnosis of carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma and amelanotic melanoma but was subsequently correctly diagnosed by immunohistochemistry.

CASE REPORT

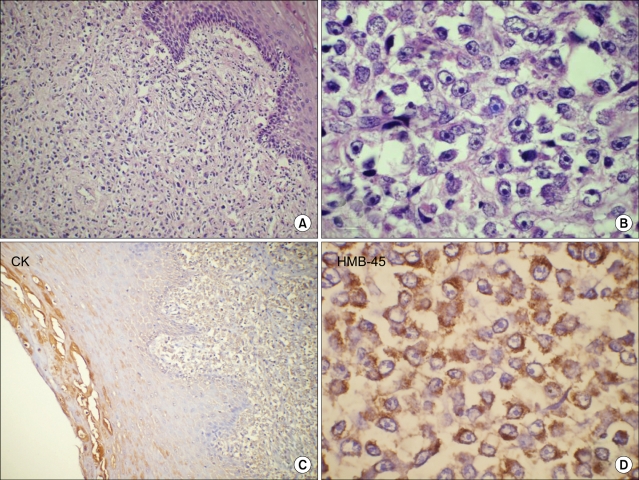

A 65-year-old postmenopausal female presented with bleeding per vagina of 4 months duration. There were no urinary or bowel symptoms. Past and family history was not contributory. On general examination patient had a cachetic built but without any systemic symptoms. Per speculum examination showed an ulcerated non-pigmented growth involving the posterior lip of the cervix. The parametrium was not involved and the growth was primarily restricted to the cervix. Vulva and vagina were normal. The clinical diagnosis was cervical carcinoma, stage I and biopsy from growth was taken. A biopsy was taken from cervical growth by the referring gynecologist which measured 2.0×2.5×0.5 cm. Histological examination of the biopsy specimen revealed diffuse infiltration of large pleomorphic and spindle shaped cells in the cervical stroma. The cervical epithelium overlying the tumor showed focal epitheliotropism by malignant cells (Fig. 1A). The tumor cells had large oval or pleomorphic vesicular nuclei with eosinophilic cytoplasm and conspicuous eosinophilic nucleoli. Many bizarre tumor cells were also noted (Fig. 1B). No intracellular or extracellular melanin pigment was seen. As the tissue sample sent was a biopsy and not a resected specimen and as the entire biopsy was composed of tumor tissue, the depth of stromal invasion and "Breslow's thickness" could not be commented. Based on the above mentioned histomorphological features it was initially considered as a poorly differentiated malignant tumor with a wide differential diagnosis of poorly differentiated carcinoma, sarcoma, high grade lymphoma and amelanotic melanoma. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the tumor cells were strongly positive for HMB-45 (Fig. 1D); they were also positive for S-100 protein and vimentin. They were negative for leucocyte common antigen, cytokeratin (Fig. 1C), epithelial membrane antigen and smooth muscle actin. Although the tumor cells were negative with Fontana-Masson silver staining for melanin pigment, majority of the cells reacted positively with HMB-45 and S-100 protein. These findings supported the diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma of the cervix. Patient was advised radical hysterectomy and vaginectomy but she refused any mode of treatment due to her family and personal circumstances.

Fig. 1.

Paraffin section of cervical growth (A), showing diffuse sheets of round to spindle shaped undifferentiated malignant cells with focal epitheliotropism (H&E, ×100). High power (B) showing few binucleate and multinucleate bizarre tumor cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (H&E, ×400). No pigment was seen within the tumor. Tumor cells were negative for cytokeratin (C, streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase CK, ×100) and show strong immunoreactivity for HMB-45 antigen (D, streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase HMB-45, ×400).

DISCUSSION

Amelanotic melanoma is a rare melanoma of the female genital tract. An occasional series or case reports have been documenting amelanotic melanoma originating exclusively in the vulva and uterine cervix.2-9 Ragnarsson-Olding reported that 27% of all vulvar melanomas are amelanotic type, however the incidence of cervical amelanotic melanoma is not yet known.9,10 The possibility of cervical melanoma was doubted for a long time because the organ was not believed to contain melanocytes, hence it is very important to rule out a melanoma elsewhere in the body before a diagnosis of primary cervical melanoma is made. Moreover, cervix is not a common site for metastatic malignancies, as it has a limited blood supply and the cervical fibrous stroma provides a poor site for growth of tumors. According to Morris and Taylor,11 the four criteria for the diagnosis of primary localization of melanoma are 1) presence of melanin in the normal cervical epithelium, 2) absence of melanoma elsewhere in the body, 3) demonstration of junctional change in the cervix, and 4) metastasis according to the pattern of cervical carcinoma. These criteria have been met in a few cases, however, a primary lesion may be missed, especially if the melanoma is amelanotic. Moreover, junctional change may not always be demonstrable, especially if the lesion becomes ulcerated and metastatic epitheliotropic cervical melanoma is also a known entity.

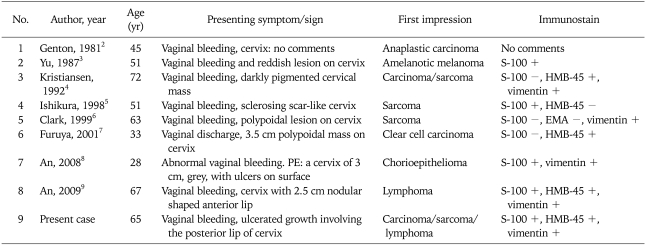

Accurate diagnosis is difficult, and the problem of misdiagnosis in amelanotic melanoma is serious. In the literature reviewed, seven out of eight cases of amelanotic melanoma were once misdiagnosed as anaplastic carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, sarcoma, chorioepithelioma or lymphoma (Table 1). In our case, the tumor was non-pigmented, and melanin granules were not demonstrated by either conventional histochemical staining or Masson-Fontana silver staining. Because of these findings we initially suspected it to be a poorly differentiated carcinoma or a non-epithelial malignant tumor such as sarcoma or lymphoma. Subsequently, immunohistochemical staining for several antigens was performed and immunohistochemical staining with vimentin, S-100 and HMB-45 was strongly positive; thus, this case was finally diagnosed as an amelanotic melanoma. An extensive search for a melanotic lesion in the skin, eye and other mucosal sites was negative. Due to absence of a primary site of melanoma and the focal epitheliotropism of melanoma cells, a final diagnosis of primary cervical amelanotic melanoma was made.

Table 1.

Amelanotic melanoma originating in cervix: literature review

Immunohistochemical stains are more specific than Masson-Fontana stain for amelanotic melanoma. Immunohistochemical stain for S-100 protein was initially used for diagnosing melanoma. Later, HMB-45 was found to be more specific for melanoma, as it stains a 10 kDa cytoplasmic glycoprotein thought to be part of the premelanosome complex and it can differentiate melanoma from benign cells containing containing melanin. A combination of S-100 protein (more sensitive) or HMB-45 (more specific) is the best combination for an accurate diagnosis, and is useful in distinguishing amelanotic melanoma from anaplastic carcinoma, high grade lymphoma and sarcoma.3-9 MART-1, and tyrosinase are other immunohistochemical markers which are positive in small percentage of HMB-45 negative melanomas.8,9 Since the present case showed strong positivity for vimentin, S-100 and HMB-45 additional immunohistochemistry was not required.

Treatment for amelanotic melanoma is the same as that for pigmented melanoma, however appropriate therapy is not standardized for this tumor.3-9 Moreover, delayed diagnosis and advanced stage can further increase the difficulty in management. For amelanotic melanoma in the cervix, most authors have recommended radical hysterectomy and if necessary, to obtain clean surgical margins of at least 2 cm.7-9 Regional lymphadenectomy has no defined role in the routine treatment. Single and multidrug chemotherapy has been used in these patients, but the regimes have not been standardized. Radiotherapy reduces the tumor bulk substantially, and has been used in patients with advanced disease as a palliative therapy. The prognosis is similar to melanoma elsewhere in the body. The disease can take a fulminant course with development of distant metastasis or may remain quiescent for a few years, manifesting elsewhere in the body later. However, the prognosis is usually poor, most patients die within 3 years of diagnosis.7-9

Biopsy for the malignant melanoma in cervix has high misdiagnosis rate. Special staining and immunohistochemistry should be resorted to, whenever needed, to reach the diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma as early as possible. This is essential since cervical melanoma is incurable even with the currently available therapies.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Mousavi AS, Fakor F, Nazari Z, Ghaemmaghami F, Hashemi FA, Jamali M. Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: case report and review of the literature. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2006;10:258–263. doi: 10.1097/01.lgt.0000229564.11741.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genton CY, Kunz J, Schreiner WE. Primary malignant melanoma of the vagina and cervix uteri: report of a case with ultrastructural study. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1981;393:245–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00431080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu HC, Ketabchi M. Detection of malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix from Papanicolaou smears: a case report. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kristiansen SB, Anderson R, Cohen DM. Primary malignant melanoma of the cervix and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;47:398–403. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90148-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishikura H, Kojo T, Ichimura H, Yoshiki T. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: a rare primary malignancy in the uterus mimicking a sarcoma. Histopathology. 1998;33:93–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.0415h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark KC, Butz WR, Hapke MR. Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: case report with world literature review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1999;18:265–273. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199907000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuya M, Shimizu M, Nishihara H, Ito T, Sakuragi N, Ishikura H, et al. Clear cell variant of malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:409–412. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An J, Wu L, Li B, Lu H, Li N, Ma S. Primary malignant amelanotic melanoma in the female genital tract: a report of six cases and a review of the literature. Chinese J Clin Oncol. 2008;5:383–386. [Google Scholar]

- 9.An J, Li B, Wu L, Lu H, Li N. Primary malignant amelanotic melanoma of the female genital tract: report of two cases and review of literature. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:267–270. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32831993de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ragnarsson-Olding BK. Primary malignant melanoma of the vulva: an aggressive tumor for modeling the genesis of non-UV light-associated melanomas. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:421–435. doi: 10.1080/02841860410031372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norris HJ, Taylor HB. Melanomas of the vagina. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;46:420–426. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/46.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]