Abstract

Recent research using word recognition paradigms such as lexical decision and speeded pronunciation has investigated how a range of variables affect the location and shape of response time distributions, using both parametric and non-parametric techniques. In this article, we explore the distributional effects of a word frequency manipulation on fixation durations in normal reading, making use of data from two recent eye movement experiments (Drieghe, Rayner, & Pollatsek, 2008; White, 2008). The ex-Gaussian distribution provided a good fit to the shape of individual subjects’ distributions in both experiments. The frequency manipulation affected both the shift and skew of the distributions, in both experiments, and this conclusion was supported by the non-parametric vincentizing technique. Finally, a new experiment demonstrated that White’s (2008) frequency manipulation also affects both shift and skew in RT distributions in the lexical decision task. These results argue against models of eye movement control in reading that propose that word frequency influences only a subset of fixations, and support models in which there is a tight connection between eye movement control and the progress of lexical processing.

It is well known that the time the eyes spend on a word in reading is a function of a range of linguistic factors (see Staub & Rayner, 2007; Rayner, 1998, 2009, for reviews). For example, a word’s printed frequency (Inhoff & Rayner, 1986; Rayner & Duffy, 1986) and its predictability in context (Ehrlich & Rayner, 1981; Rayner, Ashby, Pollatsek, & Reichle, 2004) each have substantial effects on measures such as the duration of the reader’s first eye fixation on the word (first fixation duration), and the summed duration of all fixations before the eyes leave the word (gaze duration); as frequency and predictability each decrease, the mean durations increase.

These empirical findings are among the benchmark phenomena that models of eye movement control in reading such as E-Z Reader (Pollatsek, Reichle, & Rayner, 2006; Reichle, Pollatsek, Fisher, & Rayner, 1998; Reichle, Rayner, & Pollatsek, 2003) and SWIFT (Engbert, Nuthmann, Richter, & Kliegl, 2005) attempt to account for. In E-Z Reader, for example, it is the progress of lexical processing that determines when a saccade program will be initiated. Specifically, the model proposes that a saccade is initiated when the word processing system has completed an initial stage of processing, referred to as L1 (originally termed a familiarity check), on the fixated word, and that word frequency and predictability additively influence how long this stage takes to complete (Rayner et al., 2004).

There remains, however, a family of theories of eye movement control in reading which, while not denying the existence of linguistic influences on eye fixations, propose that they are the exception rather than the rule. Yang and McConkie (2001, 2004; McConkie & Yang, 2003; Yang, 2006; see also Feng, 2006; O’Regan, 1990) have argued that the durations of most fixations are unaffected by ongoing cognitive processing of the text, at either the lexical level or at higher (e.g., syntactic) levels, but rather are a function of low-level perceptual processing and fixed oculomotor routines. Yang and McConkie used an experimental paradigm in which normal text was replaced during an eye movement with strings of nonsense letters or Xs; they examined how and which fixations durations were affected by the display change. On the basis of their results, they proposed that the distribution of fixation durations arises from a mixture of three qualitatively distinct types of fixations: very short fixations, the durations of which cannot be affected by cognitive processing; “normal” fixations, which are vulnerable to being affected by cognitive processing due to saccade cancellation; and long fixations, which reflect instances in which the saccade that would have terminated a normal fixation is cancelled due to higher-level processing difficulty, and a new saccade must then be programmed. Yang and McConkie proposed that cognitive or linguistic processing influences mean fixation duration by changing how frequently saccades that would have terminated “normal” fixations are canceled and replaced by later saccades. Thus, they suggested that a variable such as word frequency does not have a general, and graded, effect on the time that the eyes spend on a word; instead, a low frequency word simply increases the probability of an error signal that causes cancellation of the initial saccade plan. Yang and McConkie (2004) noted that “this implies a discrete basis for control of the durations of individual fixations, where, in most cases, either the normal saccade occurs or it is canceled and another saccade is generated later, rather than a fine-grained adjustment of fixation time based on the current language processing needs” (p. 419).

The goal of the present work was to assess these competing perspectives on how linguistic processing influences fixation time, by investigating distributions of fixation durations in normal reading, and specifically, the effect of word frequency on these distributions. A sizable literature using single word recognition paradigms such as lexical decision, speeded pronunciation (sometimes referred to as “naming”), and semantic categorization (Andrews & Heathcote, 2001; Balota & Speiler, 1999; Balota, Yap, Cortese, & Watson, in press; Plourde & Besner, 1997; Yap & Balota, 2007; Yap, Balota, Cortese, & Watson, 2006; Yap, Balota, Tse, & Besner, 2008) has demonstrated that individual subjects’ response time (RT) distributions in these tasks are single-peaked and right-skewed. Thus, these distributions can be well fit by the ex-Gaussian distribution (Ratcliff, 1979), which is the convolution of a normal distribution and an exponential distribution, with two parameters corresponding to the normal component (μ, the mean, and σ, the standard deviation), and a single exponential parameter (τ). Fitting of the ex-Gaussian distribution to individual subject data has allowed researchers to assess the proportion of an experimental effect on mean RT that is due to a change in the location of the normal component (i.e., an effect on μ), and the proportion that is due to a change in the degree of skew (i.e., an effect on τ). Several research groups (Andrews & Heathcote, 2001; Balota & Speiler, 1999; Plourde & Besner, 1997; Yap & Balota, 2007) have demonstrated that in fact a frequency manipulation has both kinds of effects: The distributions for low-frequency words are shifted to the right compared to distributions for high-frequency words, and are also increased in skew. The distributional shifting suggests that in single word paradigms, a word frequency manipulation affects the duration of some processing stage or component that is operative on all (or at least most) trials, while the change in skew indicates that a subset of RTs are slowed more dramatically.

It has previously been observed that distributions of fixation durations in normal reading are roughly normal, but with some degree of right skew, and that a frequency manipulation appears to shift the location of the distribution of fixation durations (Rayner, 1995; Rayner, Liversedge, White, & Vergilino-Perez, 2003; White, 2008), as would be predicted by E-Z Reader. However, these distributional observations are based on visual inspection of group distributions, from which inferences to individual subject distributions should be made only with caution (e.g., Ratcliff, 1979; it should be noted that Yang & McConkie’s conclusions are also based on analysis of group distribution functions). The lack of attempts in the literature to describe individual subjects’ distributions of fixation durations can be attributed to the fact that in most eye movement experiments the number of observations in each experimental condition, for each subject, falls far short of the number required to perform such analyses (Heathcote, Brown, & Mewhort, 2002; Speckman & Rouder, 2004); it is common to include as few as eight or ten trials per condition.

In the present work, we fit the ex-Gaussian distribution to individual subject data from two recently published eye movement experiments (Drieghe, Rayner, & Pollatsek, 2008; White, 2008) in which a relatively large number of observations were collected in high- and low-frequency conditions. We also analyzed the shapes of fixation time distributions non-parametrically, by examining the characteristic shapes of individual subject distributions in the form of vincentile plots (e.g., Andrews & Heathcote, 2001; Balota et al., in press; Yap & Balota, 2007). To anticipate the results, it appears that the shape of distributions of fixation durations is fit extremely well by the ex-Gaussian distribution, and that in both experiments, these distributions were both shifted to the right and increased in skew in the low-frequency condition compared to the high-frequency condition. To enable a direct comparison between the distributional patterns evident in fixation durations during sentence reading and in single word RT, we then carried out a new lexical decision experiment using the critical words employed by White (2008).

It should be noted that there are clear limitations on the inferences that can be drawn from ex-Gaussian fitting. First, it is not obvious that the ex-Gaussian provides a better fit to empirical RT data than do other parametric estimators of distribution shape such as the Wald or the gamma distributions (Van Zandt, 2000). Second, it should not be assumed that data which are well fit by the ex-Gaussian distribution are literally generated by two underlying processes occurring in succession, one with normally-distributed finishing times, and the other with exponentially-distributed finishing times. Relatedly, while there have been several interesting attempts to give concrete psychological interpretations to the μ and τ components of RT distributions (see Luce, 1986, for discussion), there is also reason to be skeptical of any straightforward mapping of these components to psychological processes (Matzke & Wagenmakers, 2008; Yap, Balota, Tse, & Besner, 2008).

Thus, our use of the ex-Gaussian distribution is motivated by three straightforward considerations. First, it is of interest to determine whether empirical distributions of fixation durations are well fit by the ex-Gaussian, as are distributions of RTs in single word paradigms. Second, partitioning the frequency effect on fixation durations into effects on distinct ex-Gaussian parameters enables direct comparison with the existing single-word literature, in which it is clear that a frequency manipulation affects both μ and τ. Finally, changes in the μ parameter across experimental conditions can indeed be interpreted, in a descriptive, relatively theory-neutral manner, as reflecting an effect that occurs on all, or at least most, experimental trials, an outcome that is not predicted by either the specific saccade-cancellation account of Yang and McConkie (2001, 2004), or more generally by any account that restricts the influence of the fixated word’s frequency to a subset of fixations.

This paper proceeds as follows. Study 1 consists of a distributional analysis of the eye movement data collected by Drieghe et al. (2008), in an experiment originally designed to investigate an unrelated issue, namely, so-called “parafoveal-on-foveal” effects (e.g. Kennedy & Pynte, 2005). In a 2 × 2 design, this experiment manipulated both the frequency of a critical noun (word n) and whether the next word (word n+1) was fully visible to the reader prior to direct fixation, or was replaced by a nonword until the eyes fixated word n+1 directly (a preview manipulation; Rayner, 1975). There were 25 observations per subject in each of the four conditions, but there was no hint of an interaction between the two manipulations on word n (and indeed, no significant interaction on word n+1), so it is possible to combine across the levels of the preview manipulation for the purpose of investigating the effects of frequency on distributions of fixation durations on word n. In Study 2, we assessed the reliability of the findings from Study 1 by conducting similar distributional analyses of data collected by White (2008), in a completely unrelated experiment with different materials and different subjects. In White’s (2008) experiment, each subject read 39 sentences containing a critical high-frequency word, and another 39 containing a low-frequency word. (They also read 39 sentences in a third experimental condition, discussed below.) Finally, in Study 3 we presented the critical words from White’s (2008) study in a separate lexical decision experiment, in order to assess the degree of correspondence between the distributional effects of frequency on eye movements and on single word RT, when the same words are employed in the two paradigms.

Study 1

Method

Complete methodological details are provided by Drieghe et al. (2008); a shorter summary will be provided here. The eye movements of twenty-eight members of the University of Massachusetts community were monitored by a Dual Purkinje Image tracker as these subjects read individual sentences displayed on a monitor. The subjects’ task was to read normally and to answer yes/no comprehension questions by means of a button press. One hundred sentences were presented in a random order to each subject, following 10 practice sentences. Each subject read 25 sentences in each of four conditions, exemplified by (1a–d) below, with the critical words in italics.

-

1.

The opera was very proud to present the young child performing on Tuesday. (HF noun, correct preview)

The opera was very proud to present the young child pxvforming on Tuesday. (HF noun, incorrect preview)

The opera was very proud to present the young tenor performing on Tuesday. (LF noun, correct preview)

The opera was very proud to present the young tenor pxvforming on Tuesday. (LF noun, incorrect preview)

In conditions (b) and (d), the incorrect preview was replaced by the correct word during an eye movement (Rayner, 1975), when the reader’s eyes crossed the space between the two critical words. Subjects are usually unaware of the presence of the nonword and the display change.

The mean frequency counts for the high-frequency and low-frequency nouns, based on the Francis and Ku era (1982) norms, were 163 per million and 8 per million, respectively. All critical nouns were five letters in length, and the sentences were normed to ensure that the critical nouns were not predictable from the preceding context.

Results and Discussion

The full pattern of results is reported in Drieghe et al. (2008). We focus on the first fixation duration measure, which is most central for the questions of interest. We also examine gaze duration, though we note that from the point of view of distributional analyses this is a “hybrid” measure, with most observations representing only one fixation, but some observations representing two fixations. (On the single fixation duration measure, which is the duration of eye fixations on those trials on which the reader made exactly one fixation on the critical word before moving on, all results were essentially identical to first fixation duration, both in terms of the mean, and in terms of the distributional analyses.) On the critical noun there were highly significant effects of frequency on both first fixation duration (285 ms vs. 260 ms; p < .001) and gaze duration (294 ms vs. 267 ms; p < .001). There were no effects on the noun of the preview manipulation of the next word (Fs < 1), and there were no interaction effects (Fs < 1). Readers only rarely made multiple first pass fixations on this word, doing so on 3.9% of trials in the high-frequency conditions, and on 4.7% of trials in the low-frequency conditions.

As noted above, the data were collapsed across the preview conditions for the purpose of distributional analysis in the low- and high-frequency conditions, allowing for a maximum of 50 observations for each of the two levels of word frequency. However, a substantial number of trials were excluded from analyses, either because the display change did not occur at precisely the right time (i.e., it was either initiated or completed during a fixation, rather than during the critical saccade), or because the reader did not make a first-pass fixation on the critical word. (Note that incorrect display change could be grounds for exclusion even in conditions (a) and (c), in which technically there was also a change, as the experimental software replaced the target word with itself.) As a result, there was an average of 29.7 usable observations per subject in the high-frequency condition (with a range from 14 to 43, out of a maximum possible of 50), and an average of 27.6 usable observations per subject in the low-frequency condition (with a range from 9 to 47). Because the number of observations frequently fell below the number that has been regarded as safely delivering reliable ex-Gaussian parameter estimates (i.e., approximately 40; Heathcote et al., 2002, Speckman and Rouder, 2004), we considered it especially important to confirm the pattern of results using a non-parametric method, as described below, and to confirm the pattern across multiple experiments.

The ex-Gaussian distribution was fit to the data from each subject, in each condition, using the QMPE software developed by Heathcote et al. (2002; Cousineau, Brown, & Heathcote, 2004).1 The fitting procedure divides the empirical distribution into quantiles (i.e., bins with an equal number of observations in each), then uses maximum likelihood estimation to determine the distributional parameters that come closest to producing the correct quantile boundaries, allowing all three parameters to vary freely. Heathcote et al. (2002; see also Rouder, Lu, Speckman, Sun, & Jiang, 2005) found that the best fits are delivered when the maximum number of possible quantiles is used, i.e., with each data point in a separate bin; this method was used in the present research. All distributions were successfully fit, as assessed by an algorithm internal to the QMPE software; below, we discuss the quality of fit. Once the best fitting parameters for each distribution are extracted, statistical analyses in which these parameter values function as dependent variables may be used to address the question of whether the experimental manipulations induce changes in μ, σ, τ, or some combination of these parameters.

The mean values of each of the ex-Gaussian parameters, in each condition, are shown in Table 1. Recall that the μ parameter represents the mean of the normal component, the σ parameter represents the standard deviation associated with the normal component, and τ represents the contribution of an exponentially-distributed variable, which is manifested in terms of the degree of rightward skew. On the first fixation measure, the 16 ms difference in the μ parameter was highly significant (t(27) = 4.40, p < .001), while the 8 ms difference in σ was marginal (t(27) = 1.89, p = .07), and the 10 ms difference in τ was also marginal (t(27) = 1.97, p = .06). On the gaze duration measure, the 8 ms difference in the μ parameter was not significant (t(27) = 1.38, p = .18), and neither was the 4 ms difference in σ (t(27) = .75, p = .46). However, the 20 ms difference in τ was significant (t(27) = 2.67, p < .02). Thus it appears, based on the mean ex-Gaussian parameters, that the frequency effect on first fixation duration was due primarily to distributional shifting in the low-frequency condition, though there is also a strong hint of increased skewing in this condition; the frequency effect on gaze duration was due primarily to an increase in skew in the low-frequency condition. Figure 1 illustrates density functions associated with the mean ex-Gaussian parameters for the high- and low-frequency conditions, on the first fixation duration and gaze duration measures. These are based on 20,000 random samples from each distribution, where each sample is generated by summing a sample from a Normal distribution with mean μ and standard deviation σ and a sample from an exponential distribution with rate parameter = 1/τ.

Table 1.

Study 1 mean reading time on first fixation and gaze duration measures, in ms, and mean ex-Gaussian parameters, by condition.

| mean | μ | σ | τ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First fixation duration | ||||

| High Frequency | 260 | 206 | 40 | 55 |

| Low Frequency | 285 | 222 | 48 | 65 |

| frequency effect | 25 | 16 | 8 | 10 |

| Gaze duration | ||||

| High Frequency | 267 | 211 | 41 | 59 |

| Low Frequency | 294 | 219 | 45 | 79 |

| frequency effect | 27 | 8 | 4 | 20 |

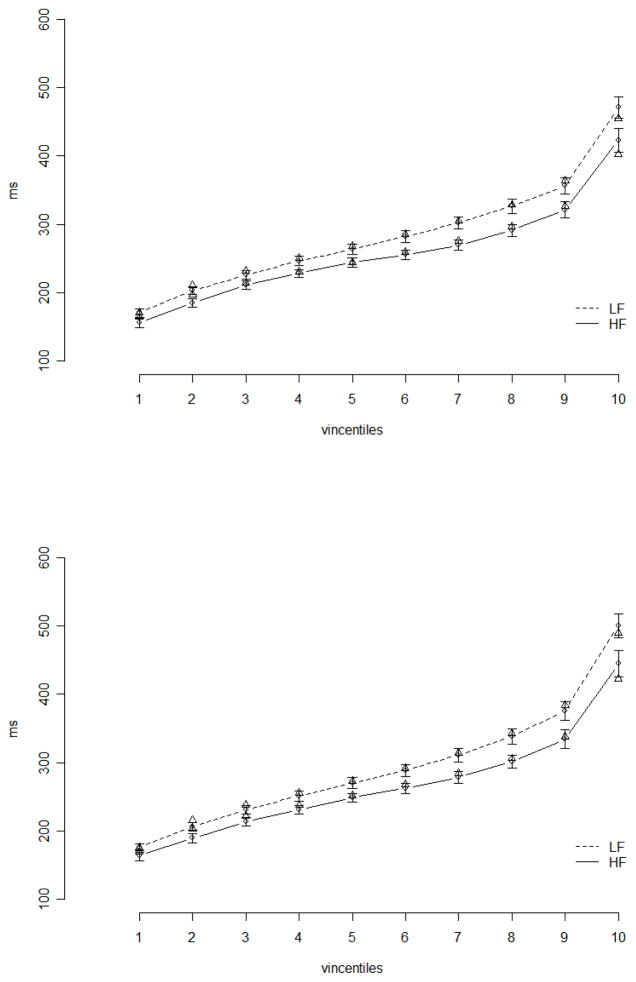

Figure 1.

Density functions generated from best-fitting ex-Gaussian parameters in Study 1, for high-frequency (HF) and low-frequency (LF) conditions; first fixation duration (upper panel), and gaze duration (lower panel).

As an additional, nonparametric means of assessing the distributional effects of the frequency manipulation, and as a means of assessing the fit of the extracted ex-Gaussian parameters to the typical distribution shape, we constructed vincentile plots (Ratcliff, 1979; Vincent, 1912) of the data in each condition, as is common in the single-word literature (see, e.g., Andrews & Heathcote, 2001; Balota et al., in press; Yap & Balota, 2007). These plots are constructed as follows. The individual observations for each subject, in each condition, are divided into the shortest 10% (vincentile 1), next shortest 10% (vincentile 2), etc.2 The mean of the observations in each vincentile is then computed. Finally, the mean of all individual subject values is computed, for each vincentile, and these values (and standard errors) are displayed as connected points on a plot with vincentile on the x-axis and fixation time in ms on the y-axis. Thus, the plots illustrate how fixation time changes across the typical individual subject distribution (as opposed to the group distribution, which may be very different in shape). The steepness of a curve’s slope, at the right side of the graph, indicates the degree of right skew present. If a difference between two condition means is due to a rightward shift, with no change in the degree of skew, then the curves corresponding to the two conditions will be parallel, with the curve representing the slower condition appearing above the curve representing the faster condition across the full range of vincentiles. If a difference between two condition means is due entirely to increased skew in one condition, then the vertical distance between the corresponding curves will be small or nonexistent for the vincentiles on the left side of the graph, but larger on the right (i.e., for the slowest part of the distributions). A difference that is due both to a change in the location of the distribution and to a change in skewness will be manifested in a vertical separation that is present along the full range of vincentiles, but which is larger on the right than on the left.

The first two panels of Figure 2 are vincentile plots for the first fixation and gaze duration data, respectively. On each plot, there is a separation between the high frequency and low frequency conditions all along the distribution, with slightly greater separation on the right side of the graph. Superimposed on the plots are triangles representing predicted vincentile values obtained from the simulated ex-Gaussian distributions shown in Figure 1. The proximity of these predicted values to the actual vincentile values indicates that the mean ex-Gaussian parameters do capture the typical distribution shapes; see Andrews and Heathcote (2001), and Yap et al. (2008) for discusion of this visual method for assessing ex-Gaussian fit. Note that if an empirical distribution is not actually well described as ex-Gaussian (e.g., it is a bimodal distribution with truly distinct peaks), this visual test will indeed fail, as the predicted vincentile values will tend to fall outside the range of the standard error bars around the observed values; see Andrews & Heathcote, 2001, Figure 1, for an example of a moderate misfit. The final panel of Figure 2 illustrates the size of the frequency effect across the range of vincentiles, i.e., the mean difference between the low-frequency and high-frequency value, for both first fixation and gaze duration, as well as the standard error of this difference.

Figure 2.

Top and middle panels: vincentiles for high-frequency (HF) and low-frequency (LF) conditions in Study 1, for first fixation duration (top panel) and gaze duration (middle panel). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Predicted vincentiles based on mean ex-Gaussian parameters are represented by triangles. Bottom panel: Mean difference between conditions at each vincentile, with standard errors.

In sum, the vincentile plot for the first fixation duration data confirms that the frequency effect appears across the distribution, and is somewhat larger at the right edge of the distribution. The plot for gaze duration suggests an essentially similar pattern, though the ex-Gaussian analysis did not find a significant shift effect in the gaze duration data. These plots also make clear that the mean ex-Gaussian parameters capture the typical distribution shape extremely well, despite the relatively small number of observations available from some subjects. The goal of Study 2 was to determine whether similar patterns would be observed in data from an unrelated study.

Study 2

White (2008) compared reading times on high frequency words to reading times on two sets of low frequency words. These two latter sets were matched on frequency, but were distinguished based on the token frequency of the individual letters, and multi-letter strings, within the word; this latter variable was referred to as orthographic familiarity. For one set, referred to as the infrequent, orthographically familiar words, orthographic familarity was comparable to the high frequency words, while for the other set, referred to as the infrequent, orthographically unfamiliar words, orthographic familiarity was substantially lower. White obtained a sizable word frequency effect in the comparison of the high and low frequency words that were matched on orthographic familiarity, with longer reading times on the infrequent, orthographically familiar words than on the frequent words, on several eye movement measures. A smaller orthographic familiarity effect was also evident, with longer reading times on the infrequent, orthographically unfamilar words than on the infrequent, orthographically familiar words. For present purposes, we focus entirely on the former comparison, and for brevity (both for Study 2 and Study 3) we refer to the orthographically familiar words simply as high frequency or low frequency.3

Method

Complete methodological details are provided in White (2008); a shorter summary will be provided here. Thirty students at the University of Durham, United Kingdom, had their eye movements monitored by a Dual Purkinje Image eye tracker as they read. Their task was to read normally and to answer yes/no comprehension questions. A list of 117 experimental sentences was presented in a fixed pseudorandomized order to each subject, following six practice sentences. In each of the experimental sentences, a critical word appeared; there were 39 sentences with each of three types of critical word. The critical word types were: frequent, orthographically familiar (e.g., door); infrequent, orthographically familiar (e.g., gong); and infrequent, orthographically unfamiliar (e.g., tusk). The words were grouped into triplets in which the critical words were matched on length and were presented with the same preceding sentence frame. The randomization procedure ensured that the matching initial sentence frames were distributed widely through the experiment. All sentences were normed to ensure that the critical word was not predictable (see White, 2008 for details).

Critical lexical characteristics of the two sets of words of present interest were as follows. Based on the CELEX database (Baayen, Piepenbrock, & Gulikers, 1995), the mean frequencies of the words, in counts per million, were 297 for the frequent, orthographically familiar words, and 1.7 for the infrequent, orthographically familiar words. As noted above, these two sets of words did not differ on the orthographic familiarity measure. They also did not differ in the number of orthographic neighbors. All words were 4 or 5 characters long (and as noted above, matched on length within each set), with a mean of 4.5 characters.

Results and Discussion

The frequency manipulation had significant effects on both first fixation duration (280 ms vs. 253 ms; p < .001) and gaze duration (309 ms vs. 265 ms; p < .001). As in Drieghe et al. (2008), the pattern for single fixation duration mirrored first fixation duration very closely. Readers made more than one fixation on the target word 6% of the time in the high-frequency condition, and 11% of the time in the low-frequency condition. The gaze duration measure shows a considerably larger frequency effect in the White (2008) data than in the Drieghe et al. (2008) data, probably due to the fact that multiple fixations on the target word were quite rare in the Drieghe et al. study.

Because there was no display-change manipulation in this experiment, trials were excluded from distributional analysis only on the basis of word skipping, blinks, or track loss on the critical words. There was an average of 28.9 usable observations per subject in the high-frequency condition (with a range from 15 to 39, out of a maximum possible of 39), and an average of 30 usable observations per subject in the low-frequency condition (with a range from 17 to 39). Ex-Gaussian analysis was carried out using the same method as for Study 1; again, all fits were successful based on the criteria applied by the QMPE software. The mean values of the recovered parameters are shown in Table 2. On the first fixation measure, the 13 ms difference in the μ parameter was significant (t(29) = 2.34, p < .05), as was the 15 ms difference in τ (t(29) = 2.28, p < .05). On the gaze duration measure, the 17 ms difference in the μ parameter was significant (t(29) = 2.96, p < .01), as was the 28 ms difference in τ (t(29) = 3.69, p < .001). The effects on the σ parameter did not approach significance for either measure (ts < 1). Figure 3 illustrates simulated density functions based on the mean ex-Gaussian parameters for first fixation duration and gaze duration (generated by simulating 20,000 observations from each distribution).

Table 2.

Study 2 mean reading time on first fixation and gaze duration measures, in ms, and mean ex-Gaussian parameters, by condition.

| mean | μ | σ | τ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First fixation duration | ||||

| High Frequency | 253 | 208 | 43 | 42 |

| Low Frequency | 280 | 221 | 47 | 57 |

| frequency effect | 27 | 13 | 4 | 15 |

| Gaze duration | ||||

| High Frequency | 265 | 204 | 41 | 57 |

| Low Frequency | 309 | 221 | 46 | 85 |

| frequency effect | 44 | 17 | 5 | 28 |

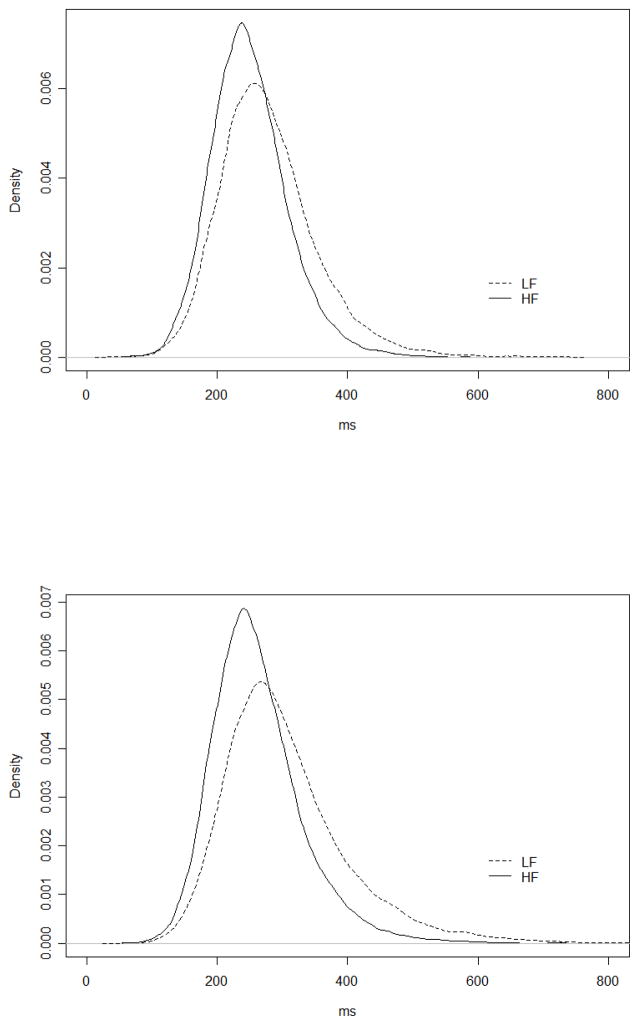

Figure 3.

Density functions generated from best-fitting ex-Gaussian parameters in Study 2, for high-frequency (HF) and low-frequency (LF) conditions; first fixation duration (upper panel), and gaze duration (lower panel).

The first two panels of Figure 4 are vincentile plots for the first fixation and gaze duration data, respectively. As in Study 1, there is separation between the high frequency and low frequency conditions all along the distribution, with greater separation on the right side of the graph. Again, it appears that the simulated distributions generated from the mean ex-Gaussian parameters produce vincentiles that are extremely close to the vincentiles in the observed data. The final panel of Figure 4 illustrates the size of the frequency effect across the range of vincentiles. Again, it is clear that the frequency effect is present along the full distribution, but is larger on the right; especially in the gaze duration data, it appears that there is a strong frequency effect on the right tail of the distribution. This strong skewing effect can be explained by the fact that in this experiment, the probability of a second fixation on the critical word was almost twice as high in the low-frequency condition as in the high-frequency condition, adding a substantial number of long gaze durations in the low-frequency condition.

Figure 4.

Top and middle panels: vincentiles for high-frequency (HF) and low-frequency (LF) conditions in Study 2, for first fixation duration (top panel) and gaze duration (middle panel). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Predicted vincentiles based on mean ex-Gaussian parameters are represented by triangles. Bottom panel: Mean difference between conditions at each vincentile, with standard errors.

Considering the analyses of both experiments, it is clear, first, that the typical shape of fixation duration distributions is fit extremely well by the ex-Gaussian distribution. This finding does not indicate that these distributions could not be generated by a mixture model, such as the model proposed by Yang and McConkie (2001, 2004) in which there are distinct sub-populations of fixations; indeed, it is very likely that a mixture model, with suitably chosen parameters, could be made to mimic this shape. However, there is clearly no direct support for a mixture model in the data. Yang and McConkie (2001, 2004) do report multi-modal distributions of fixation durations, but as noted above, these appeared in group distributions, and moreover, in experiments involving altered text rather than normal reading.

Second, it is clear that the effect of word frequency on the duration of readers’ first fixation on a word is due both to a shifting of the distribution of fixation durations to the right, and to an increase in the degree of skewing. These conclusions emerged from both the ex-Gaussian analysis, which revealed significant effects of frequency on μ and significant or marginal effects on τ in both experiments, and from the vincentizing procedure, which revealed a distributional shifting for low-frequency words, with the most pronounced frequency effect emerging in the highest vincentiles. The gaze duration conclusions are generally similar, though the effect of frequency on μ was significant in the White (2008) experiment, but not in the Drieghe et al. (2008) experiment.

The specific type of mixture model proposed by Yang and McConkie (2001, 2004) would appear to have difficulty accounting for the finding of a distributional shift, affecting even the leading edge of the distribution, based on a frequency manipulation. Yang and McConkie (2001) reported that altering normal text during a saccade by replacing the spaces between words with non-letter symbols, or even by replacing all words with nonwords or with strings of Xs, had no effect whatsoever on the duration of fixations shorter than about 175–200 ms, and argued on this basis that there is a population of relatively short fixations that is unaffected by cognitive or linguistic processing of the text. But the present data suggest that word frequency affects the duration of most of a reader’s encounters with an input word, and provide no evidence of a qualitative distinction between the effect on short fixations and the effect on longer fixations.

Still, it is clear that some fixation durations are affected more dramatically than others, as evidenced by the more pronounced effect on the right tail of the distribution, and this finding might be regarded as consistent with a somewhat modified saccade-cancellation account. Such an account would allow that frequency does affect the duration of “normal” fixations, but would also claim that saccade cancellation plays an important role, as processing difficulty on a low-frequency word sometimes does lead to cancellation of an initially-programmed saccade. But alternately, the especially large effect of frequency on the right tail of the distribution may simply reflect the distribution of finishing times of the underlying word recognition processes that must be completed before a saccade is programmed. In terms of the E-Z Reader model, for example, it might be proposed that the skewness of the distribution of L1 (or “familiarity check”) finishing times, which must be complete before a saccade program is initiated, is affected by a frequency manipulation.

To test this idea, we explored, in Study 3, whether the specific frequency manipulation employed by White (2008) would have similar distributional affects in a word recognition task in which saccadic programming plays no role, namely lexical decision. As noted above, previous single-word experiments have generally found both μ and τ effects of a frequency manipulation, and we expected the same pattern here.

Study 3

Method

Subjects

Thirty students at the University of Leicester participated in the experiment voluntarily or for course credit; none had participated in the experiment by White (2008). The subjects were native English speakers, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and were naive regarding the purpose of the experiment. One subject was excluded and replaced due to an exceptionally high error rate for the critical words (18%).

Materials

The same 117 stimulus words used in White (2008) were intermixed with 115 nonwords4. As there were no sentence frames presented in common for members of the three sets of words, the word type manipulation is best regarded as a within-subjects, but between-items, manipulation in this experiment. The lengths of the nonwords were matched to the lengths of the words. In order to encourage lexical decisions to be made on the basis of lexical access rather than orthographic familiarity, the nonwords were constructed so as to be orthographically similar to the words; 76 of the nonwords were matched on the orthographic familiarity measure to the orthographically familiar words, and 39 nonwords were matched on this measure to the orthographically unfamiliar words. Note that as a result of this control, many of the nonwords were similar to real words, for example creat or frowe. The items were presented in a random order to each subject.

Procedure

The experiment was run using E-Prime software (Schneider, Eschmann, & Zuccolotto, 2002) on a PC with a 17 inch LCD monitor with a refresh rate of 60 Hz. Subjects responded using a Psychology Software Tools Serial Response Box. The stimuli were presented in 18 pt Courier font in black on a white background. Subjects undertook the experiment individually in a quiet room and the viewing distance was approximately 60 cm. Having read the instructions, they completed one block of six practice trials, followed by five blocks of experimental trials, between which subjects could take a short break if they wished. On each trial, the target stimulus appeared in the center of the screen until the subjects pressed a response key. Subjects responded with the left hand key if they thought the target was a nonword, and with the right hand key if they thought the target was a word. The entire session lasted approximately 15 minutes.

Results and Discussion

We focus on the two conditions of present interest, i.e., the frequent, orthographically familiar words and the infrequent orthographically familiar words, referred to here simply as low or high frequency, as in Study 2. Table 3 provides the mean accuracy and correct RT for each of these word types, as well as for the orthographically unfamiliar words, and for the orthographically familiar and unfamiliar nonwords.

Table 3.

Study 3 proportion correct and mean RT (sd) for correct responses, and mean ex-Gaussian parameters correct responses in critical conditions.

| accuracy | mean (sd) | μ | σ | τ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Words | |||||

| Frequent, orthographically familiar | .997 | 620(194) | 495 | 42 | 124 |

| Infrequent, orthographically familiar | .929 | 754(280) | 537 | 41 | 220 |

| frequency effect | .068 | 134 | 41 | −1 | 96 |

| Infrequent, orthographically unfamiliar | .840 | 823(305) | |||

| Nonwords | |||||

| Orthographically familiar | .94 | 838(326) | |||

| Orthographically unfamiliar | .95 | 781(268) | |||

Accuracy was higher for the high frequency words than for the low frequency words (t1(29) = 9.36, p < .001, t2(76) = 3.97, p < .001). For the analysis of RT, errors were excluded, as were responses shorter than 250 ms or longer than 3000 ms (0.2% of trials). We did not exclude additional observations based on cutoffs for each subject, in order to maintain maximum comparability to the analyses of the White (2008) experiment, for which a single fixed criterion was used, as is common in the eye movement literature. (Fixations shorter than 80 ms or longer than 1200 ms were excluded; see White, 2008, for details.) Moreover, it is arguably the case that routines for excluding outliers should be especially conservative when the right tail of the distribution is of particular interest, and when the degree of skew is hypothesized to vary across conditions, as in the present case (see, e.g., Heathcote, Popiel, & Mewhort, 1991; Ratcliff, 1993). In addition, in order to maintain strict comparability to the eye movement analyses, we also conducted analyses in which error responses were not excluded, as there are no “errors” in the eye movement data. There were no notable differences between the patterns of results for these analyses and for the analyses in which errors were excluded (all statistical tests, for both mean RT and for the ex-Gaussian parameters, delivered the same verdict), so we report only the latter. Mean RT, shown in Table 3, was significantly shorter for the high frequency words than for the low frequency words (t1(29) = 10.79, p < .001; t2(76) = 7.83, p < .001).

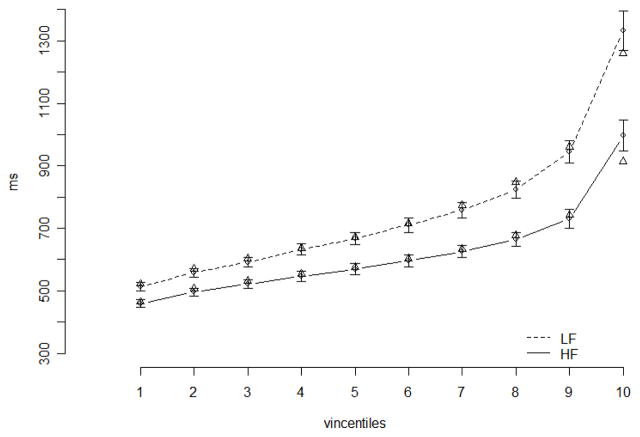

Ex-Gaussian parameters were estimated for the word stimuli using the same procedure used for Studies 1 and 2. The mean values of each of the three parameters, for the critical conditions, are shown in Table 3. There were significant differences between the conditions in the μ parameter (t(29) = 5.70, p < .001) and in the τ parameter (t(29) = 6.97, p < .001), but not in the σ parameter (t < 1). The absolute size of the effect on the τ parameter was more than twice the effect on the μ parameter. Figure 5 displays density functions based on sampling 20,000 times from simulated distributions generated from these parameters.

Figure 5.

Density functions generated from best-fitting ex-Gaussian parameters in Study 3, for high-frequency (HF) and low-frequency (LF) conditions.

Figure 6 displays vincentile plots for the critical conditions in Study 3. It is clear that there is separation between the two conditions all along the distributions, but that this separation is greatest on the right side of the graph. Again, the vincentiles generated from the mean ex-Gaussian parameters provide a remarkably good fit to the observed vincentiles. The one exception to this is at the slowest vincentile, where the ex-Gaussian appears to underestimate the actual values; there is also a very slight hint of such underestimation in Figures 2 and 4. Interestingly, Ratcliff (1979) reported a similar underestimation of the slowest RTs by the ex-Gaussian distribution in the first published study using this method.

Figure 6.

Vincentiles for high-frequency (HF) and low-frequency (LF) conditions in Study 3. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Predicted vincentiles based on mean ex-Gaussian parameters are represented by triangles.

One obvious difference between the results obtained by White (2008) and the present Study 3 is in the absolute magnitude of the frequency effect on the mean of the response measures; the frequency effects on first fixation duration and gaze duration were 27 ms and 44 ms respectively, while the effect on lexical decision RT was 134 ms. However, these differences are less striking in relative terms: The frequency effect on first fixation duration represented an increase of 10.7%, the effect on gaze duration represented an increase of 16.6%, and the effect on lexical decision RT represented an increase of 21.6%. Moreover, the one previous study that has directly compared frequency effects on eye movement measures and lexical decision RT with the same words (Schilling, Rayner, & Chumbley, 1998) obtained a very similar pattern, with effect sizes of 35 ms, 67 ms, and 149 ms on first fixation duration, gaze duration, and lexical decision RT. Thus, the difference in the size of the frequency effect between paradigms is consistent with previous work.

A second interesting finding, however, is that in lexical decision, a much larger proportion of the frequency effect on mean RT appears to be due to a change in the degree of skewing; the τ effect was more than twice as large as the μ effect in the lexical decision paradigm. Again, this finding is not entirely unexpected based on existing findings, as large frequency effects on τ have repeatedly been found in lexical decision (Andrews & Heathcote, 2001; Balota & Speiler, 1999) while the τ effect has been more variable, and sometimes quite small, in pronunciation and semantic categorization (Andrews & Heathcote, 2001; Balota & Speiler, 1999; Yap & Balota, 2007). Andrews and Heathcote (2001) discuss at length the theoretical interpretation of these differences; for present purposes, it is important to note that the effect of frequency on τ has generally been significant even in pronunciation and semantic categorization, which argues against the potential claim that this effect reflects task-specific processes rather than normal word recognition.

A second point relevant to the interpretation of the large τ effect in this lexical decision experiment is that many previous studies employing ex-Gaussian analysis have trimmed outliers much more liberally than we did, excluding all trials with RTs more than 2.5 SDs above each subject’s overall mean (e.g., Balota et al., in press; Yap & Balota, 2007; Yap, Balota, Cortese, & Watson, 2006). This trimming procedure eliminates 2–3% of trials in most experiments. More importantly, it is likely to eliminate trials differentially in different experimental conditions, assuming genuine differences between conditions in the degree of skew. Indeed, additional analyses of the present data found that adopting a 2.5 SD criterion resulted in an attenuated (but still significant) τ effect. Finally, yet another factor that may have increased the effect of the frequency manipulation on skew was the presence of relatively word-like nonwords, which may have made the decision process especially difficult for low frequency words. Nonword type in the lexical decision task has indeed been shown to differentially influence ex-Gaussian parameters (e.g., Yap et al., 2006).

With respect to the questions of interest in this article, the central finding from the present experiment is simply that in a word recognition task in which saccadic programming plays no role, there is still a frequency effect on τ; indeed, in this experiment the τ effect was very large. This finding has been repeatedly obtained in the literature, but here we replicated it using the same words employed by White (2008). Thus, there is no need to invoke occasional saccade cancellation as a mechanism for explaining the fact that distributions of fixation durations are more right-skewed for low-frequency words; this change in skew can arise due to the dynamics of word recognition itself.

Importantly, the lexical decision paradigm also provides a unique indication of whether the subjects recognized the words. It might be argued that the greater skew for low frequency words in Studies 1 and 2 might have reflected instances in which participants simply did not know the words that were read. But the presence of a strong effect of word frequency on skew in Study 3, when only correct responses were included (i.e., the subject responded “yes”), shows that the frequency of known words produces an effect on skew.

General Discussion

Our main findings can be summarized very simply. In both of the eye movement data sets analyzed here, the distributions of readers’ first fixation and gaze durations on a critical word were well fit by the ex-Gaussian distribution. In both data sets, the manipulation of word frequency affected mean fixation time both by shifting the distribution of fixation durations to the right, and by increasing the degree of skew. In other words, both short and long fixations were made longer when the fixated word was low in frequency, but long fixations were especially affected. A lexical decision experiment using the critical words employed by White (2008) found an essentially similar pattern in lexical decision RT, though here the effect on the degree of skew was especially strong.

These findings are entirely consistent with the assumption embodied in the E-Z Reader model (Pollatsek et al., 2006) that factors such as frequency and predictability influence the time the eyes spend on a word because these factors influence lexical processing itself, and it is the progress of lexical processing that causes the eye movement control system to initiate a saccade. (The SWIFT model, Engbert et al., 2005, makes the slightly different assumption that frequency and predictability determine, for each word, the amount by which a standard fixation duration is extended.) This view would predict that the durations of all, or at least most, fixations should be affected by factors such as frequency, and that effects on single-word RT and effects on eye fixation durations should be similar not only at the level of the mean, but also at the level of underlying distributional parameters. On the other hand, these findings are not easily reconciled with the claim that cognitive processing influences fixation durations only on those occasions when there is a processing problem, and an error signal overrides the usual saccade program (e.g. Yang & McConkie, 2001).

As a final exploration of the consistency of the present findings with E-Z Reader, we simulated distributions of L1 finishing times for high and low frequency words. As noted above, E-Z Reader proposes that the saccade that will terminate the first fixation on a word is programmed when the first stage of word processing (L1) is complete. L1 finishing times are sampled from a gamma distribution with standard deviation fixed at a value equal to .22 of its mean (Pollatsek et al., 2006), and its mean is derived from frequency (in counts per million) and predictability (based on cloze probability) according to the following equation: t(L1) = 122 4* ln(frequency) (10*predictability). We set predictability to zero, as was essentially the case in both the Drieghe et al. (2008) and White (2008) experiments. Figure 7 illustrates the predicted distributions for L1 finishing times for words with frequencies corresponding to the high- and low-frequency conditions in White (2008), i.e., 297 and 1.7 per million. (Note that first fixation durations, in the model, also reflect time associated with low-level perceptual processing, and time associated with saccadic programming. The latter contributes some additional skewing to the distribution of first fixation durations, but neither of these quantities is affected by word frequency.)

Figure 7.

E-Z Reader predictions for distributions of L1 finishing times in high-frequency (HF) and low-frequency (LF) conditions in the White (2008) experiment.

We then sampled from each distribution 1000 times; the resulting means were 99 ms in the high-frequency condition and 118 ms in the low-frequency condition. Finally, we obtained the best-fitting ex-Gaussian parameters. For the high-frequency condition, these were μ = 86, σ = 18, and τ = 13, and for the low-frequency condition, these were μ = 98, σ = 19, and τ = 20. In sum, a 19 ms frequency effect on the mean was partioned into a 12 ms effect on μ and a 7 ms effect on τ. If these values are compared directly with the analysis of the White (2008) data, where there was a 13 ms effect on μ and a 15 ms effect on τ, it appears that E-Z Reader may underestimate the proportion of the frequency effect that is due to a change in skew, though it should be recalled that in the analysis of the Drieghe et al. data, there was a 16 ms effect on μ and a 10 ms effect on τ. It is also important to note that the selection of the gamma distribution, and in particular the choice to fix this distribution’s standard deviation at .22 of its mean, have both been due to modeling convenience rather than to an underlying theoretical motivation. Exploratory modeling shows that if the standard deviation is set to a higher value (e.g., .30 of the mean), there is a stronger frequency effect on the degree of skew.

It should be noted that in E-Z Reader, the shift and skew of the distribution of L1 finishing times are mathematically yoked; it is not possible to influence one of these distributional properties without having at least some influence on the other. One question for future research is whether there are empirical dissociations that undermine this assumption; i.e., are there experimental manipulations that influence only the shift or skew of the distribution of first fixation durations. In sum, it is not clear whether E-Z Reader will ultimately require changes to specific parameter settings, or to its underlying architecture, to capture detailed distributional patterns.

In conclusion, the modeling exercises and new experiment presented here provide strong evidence that eye movement control is indeed tightly coupled to cognitive and linguistic processing of the text. This conclusion might be regarded as hardly needing further elaboration, as there are already some striking demonstrations of this fact, such as the finding by Rayner et al. (2003) that word frequency effects on fixation durations remain intact even when the fixated word disappears 60 ms into a fixation. However, the present work adds to this picture by showing that word frequency appears to affect the durations of most (if not essentially all) fixations, and by showing a correspondence, at a distributional level, between frequency effects on eye movements and in a single-word paradigm.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Cohen for helpful discussion, and Chuck Clifton and Caren Rotello for insightful comments on drafts of this paper. Portions of this research were supported by National Institute of Health Grant HD26765 and by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant 12/S19168. We thank Derek Besner, Albrecht Inhoff, and an anonymous reviewer for their comments on an earlier version of the paper.

Footnotes

It is customary in the ex-Gaussian literature to carry out distributional analyses only for subjects, not for items.

For the one subject who had only 9 observations in one condition, the vincentizing procedure resulted in a missing value for the first vincentile. In general, the vincentizing procedure first multiplied the total number of observations by .1, .2, etc., resulting, in most cases, in decimal values; these values were then rounded down, and the corresponding data point (with the data points ordered from fastest to slowest) was treated as the upper bound of the corresponding vincentile. For example, if there were 35 observations for a given subject in a given condition, vincentile 1 would consist of the the fastest three fixations; vincentile 2 would consist of the next four; vincentile 3 would consist of the next three, and so on.

In addition to its lack of direct relevance to the issue that is the focus of this article, the orthographic familiarity manipulation is admittedly not well understood: Letter frequency, bigram frequency, and trigram frequency all make contributions to this measure, and are highly correlated (White, 2008), and there are also unavoidable differences between the two classes of words in neighborhood size, and in spelling-sound consistency. As discussed below, we did include the orthographically unfamiliar words in the new lexical decision experiment (Study 3), primarily for consistency with the eye movement experiment.

Two additional stimuli were also included as nonwords but, due to an error in the development of materials, were actually very infrequent words.

References

- Andrews S, Heathcote A. Distinguishing common and task-specific processes in word identification: A matter of some moment? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2001;27:514–544. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.27.2.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baayen RH, Piepenbrock R, Gulikers L. The CELEX Lexical Database. Philadelphia: Linguistic Data Consortium, University of Pennsylvania; 1995. [CD-ROM] [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Spieler DH. Word frequency, repetition, and lexicality effects in word recognition tasks: Beyond measures of central tendency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128:32–55. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Yap MJ, Cortese MJ, Watson JM. Beyond mean response latency: Response time distributional analyses of semantic priming. Journal of Memory & Language (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau D, Brown S, Heathcote A. Fitting distributions using maximum likelihood: Methods and packages. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:742–756. doi: 10.3758/bf03206555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drieghe D, Rayner K, Pollatsek A. Mislocated fixations can account for parafoveal-on-foveal effects in eye movements during reading. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008;61:1239–1249. doi: 10.1080/17470210701467953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich SF, Rayner K. Contextual effects on word perception and eye movements during reading. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior. 1981;20:641–655. [Google Scholar]

- Engbert R, Nuthmann A, Richter E, Kliegl R. SWIFT: A dynamical model of saccade generation during reading. Psychological Review. 2005;112:777–813. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G. Eye movements as time-series random variables: A stochastic model of eye movement control in reading. Cognitive Systems Research. 2006;7:70–95. [Google Scholar]

- Francis WN, Ku era H. Frequency analysis of English usage: Lexicon and grammar. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Heathcote A, Brown S, Mewhort DJK. Quantile maximum likelihood estimation of response time distributions. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2002;9:394–401. doi: 10.3758/bf03196299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heathcote A, Popiel SJ, Mewhort DJK. Analysis of response time distributions: An example using the Stroop task. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:340–347. [Google Scholar]

- Inhoff AW, Rayner K. Parafoveal word processing during eye fixations in reading: Effects of word frequency. Perception & Psychophysics. 1986;40:431–439. doi: 10.3758/bf03208203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A, Pynte J. Parafoveal-on-foveal effects in normal reading. Vision Research. 2005;45:153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke D, Wagenmakers E-J. Psychological interpretation of ex-Gaussian and shifted Wald parameters: A diffusion model analysis. 2008 doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.5.798. Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConkie GW, Yang S-N. How cognition affects eye movements during reading. In: Hyona J, Radach R, Deubel H, editors. The mind’s eye: Cognitive and applied aspects of eye movement research. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2003. pp. 413–427. [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan JK. Eye movements and reading. In: Kowler E, editor. Eye movements and their role in visual and cognitive processes. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1990. pp. 395–453. [Google Scholar]

- Plourde CE, Besner D. On the locus of the word frequency effect in visual word recognition. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1997;51:181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pollatsek A, Reichle ED, Rayner K. E-Z Reader: Testing the interface between cognition and eye movement control in reading. Cognitive Psychology. 2006;52:1–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R. Group reaction time distributions and an analysis of distribution statistics. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:446–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R. Methods for dealing with reaction time outliers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:510–532. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. The perceptual span and peripheral cues in reading. Cognitive Psychology. 1975;7:65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. Eye movements and cognitive processes in reading, visual search, and scene perception. In: Findlay JM, Walker R, Kentridge RW, editors. Eye movement research: Mechanisms, processes and applications. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1995. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:372–422. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. Thirty-fifth Sir Frederick Bartlett Lecture: Eye movements and attention in reading, scene perception, and visual search. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2009 doi: 10.1080/17470210902816461. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K, Duffy S. Lexical complexity and fixation times in reading: Effects of word frequency, verb complexity, and lexical ambiguity. Memory & Cognition. 1986;14:191–201. doi: 10.3758/bf03197692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K, Ashby J, Pollatsek A, Reichle ED. The effects of frequency and predictability on eye fixations in reading: Implications for the E-Z Reader model. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2004;30:720–732. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.30.4.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K, Liversedge SP, White SJ, Vergilino-Perez D. Reading disappearing text: Cognitive control of eye movements. Psychological Science. 2003;14:385–389. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.24483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichle ED, Pollatsek A, Fisher DL, Rayner K. Toward a model of eye movement control in reading. Psychological Review. 1998;105:125–157. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichle ED, Rayner K, Pollatsek A. The E-Z Reader model of eye-movement control in reading: Comparisons to other models. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2003;26:445–526. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x03000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouder JN, Lu J, Speckman P, Sun D, Jiang Y. A hierarchical model for estimating response time distributions. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2005;12:195–223. doi: 10.3758/bf03257252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling HEH, Rayner K, Chumbley JI. Comparing naming, lexical decision, and eye fixation times: Word frequency effects and individual differences. Memory & Cognition. 1998;26:1270–1281. doi: 10.3758/bf03201199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Eschman A, Zuccolotto A. E-Prime User’s Guide. Pittsburgh: Psychology Software Tools, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Speckman PL, Rouder JN. A comment on Heathcote, Brown, and Mewhort’s QMLE method for response time distributions. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2004;11:574–576. doi: 10.3758/bf03196613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub A, Rayner K. Eye movements and on-line comprehension processes. In: Gaskell G, editor. The Oxford handbook of psycholinguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zandt T. How to fit a response time distribution. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2000;7:424–465. doi: 10.3758/bf03214357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent SB. The function of the viborissae in the behavior of the white rat. Behavioral Monographs. 1912;1(5) [Google Scholar]

- White SJ. Eye movement control during reading: Effects of word frequency and orthographic familiarity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2008;34:205–223. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.34.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SN. An oculomotor-based model of eye movements in reading: The competition/interaction model. Cognitive Systems Research. 2006;7:56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yang SN, McConkie GW. Eye movements during reading: A theory of saccade initiation time. Vision Research. 2001;41:3567–3585. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SN, McConkie GW. Saccade generation during reading: Are words necessary? European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2004;16:226–261. [Google Scholar]

- Yap MJ, Balota DA. Additive and interactive effects on response time distributions in visual word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 2007;33:274–295. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MJ, Balota DA, Cortese MJ, Watson JM. Single versus dual process models of lexical decision performance: Insights from RT distributional analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2006;32:1324–1344. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.32.6.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MJ, Balota DA, Tse C-S, Besner D. On the additive effects of stimulus quality and word frequency in lexical decision: Evidence for opposing interactive influences revealed by RT distributional analyses. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 2008;34:495–513. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]