Abstract

Objective

Despite the increasing presentation of ADHD in adults, many practitioners remain reluctant to assess individuals for ADHD, in part related to the relative lack of data on the presenting symptoms of ADHD in adulthood. Comorbidity among adults with ADHD is also of great interest due to the high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, which can lead to a more persistent ADHD among adults.

Methods

We assessed 107 adult outpatients with ADHD of both sexes (51% female; mean ± SD of 37±10.4 years) using structured diagnostic interviews. Using DSM-IV symptoms, we determined DSM-IV subtypes.

Results

Inattentive symptoms were most frequently endorsed (>90%) in ADHD adults. Using current symptoms, 62% of adults had the combined subtype, 31% the inattentive only subtype, and 7% the hyperactive/impulsive only subtype. Adults with the combined subtype had relatively more psychiatric comorbidity compared to those with the predominately inattentive subtype. Females were similar to males in the presentation of ADHD.

Conclusion

Adults with ADHD have prominent inattentive symptoms of ADHD necessitating careful questioning of these symptoms when evaluating these individuals.

Keywords: ADHD, adults, presentation, subtypes, comorbidity, sex differences

Introduction

Adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are increasingly presenting for evaluation and treatment of their disorder reflective of the clinical awareness of the chronicity of the disorder 1-3, and identification of the disorder in adults with other psychiatric disorders 4-6. Despite this awareness, many practitioners remain reluctant to assess and subsequently treat individuals for ADHD7 in part because of the relative lack of data on the presenting symptoms of ADHD in adulthood.

Prospectively collected data suggest that prominent ADHD symptom persist in approximately one-half of childhood cases into young adulthood 8 and that 4-5% of adults may have ADHD 6. Longitudinal studies also show a developmental influence on ADHD symptoms 8-10. These data suggest a decay of ADHD symptoms over time with more persistence of the inattentive symptoms of ADHD relative to the hyperactive/impulsive symptoms 8-11. In support of this notion, using DSM-III-R criteria, we previously reported higher levels of inattentive compared to hyperactive/impulsive symptoms in a sample of adults with ADHD 12. However, those data were derived from DSM-III-R necessitating replication using DSM-IV criteria and subtypes to better understand the current symptomatic presentation of adults with ADHD.

The literature also suggests that children with psychiatric comorbidities such as conduct disorder may be at higher risk for the persistence of specific subtypes of ADHD 10, 13 highlighting the important influence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders on the presentation of ADHD in older age groups. Additionally, sex differences may also effect the presentation of ADHD over time. For example, studies of girls with ADHD suggest lower rates of conduct disorder relative to boys with ADHD 14, 15 that may translate into less hyperactivity and impulsivity in adulthood. However, the effect of sex on the symptom presentation of ADHD in adults remains understudied.

Given that the diagnosis of ADHD is established through clinical history 16-18, a better understanding of manifested symptoms in adults with ADHD has the potential to increase the diagnostic precision of clinicians. To better understand the symptom profile of adults with ADHD, we systematically assessed DSM-IV ADHD symptoms in a large group of ADHD adults. We secondarily evaluated the influence of psychiatric comorbidity, sex, and age on the presentation of ADHD in adults. Based on the literature 12, we hypothesized that inattentive symptoms would be more prominent relative to hyperactive/impulsive symptoms in a sample of adults with childhood-onset and persistent ADHD. We further hypothesized that psychiatric comorbidity would be more common with the combined subtype relative to the inattentive subtype of ADHD.

Methods

Subjects

Men and women between the ages of 18 and 55 were eligible to become probands for the study. Exclusion criteria were deafness, blindness, psychosis, inadequate command of the English language, or a full-scale IQ less than 80 as measured by the IQ estimated from the block design and vocabulary subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales–Revised. No ethnic or racial group was excluded. We recruited potential probands with ADHD through advertisements in the greater Boston area and referrals to adult ADHD clinics. The institutional review board at Massachusetts General Hospital approved the study and subjects provided signed informed consent.

Assessment Measures

Trained lay interviewers, blind to ascertainment status, interviewed all adults with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) 19 and modules from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic Version (KSADS-E) 20. When we asked questions about childhood disorders, the subjects were first queried about childhood symptoms, and if they were present, they were asked about continuation of these symptoms into adulthood and the emergence of others. Age at onset was defined as the first emergence of impairing symptoms. Before interviewing for the study, interviewers completed a 4-month training program that included mastery of the instruments, learning about DSM-IV criteria, watching training tapes, observing interviews performed by experienced raters, rating several subjects under the supervision of the project coordinator and completing practice interviews. Throughout the study, they were supervised by board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists or licensed psychologists. This supervision included weekly meetings and additional consultations, as needed. During the study, all interviews were audiotaped for random quality control assessments. Final diagnostic assignment was based on the structured psychiatric interview. Initial diagnoses were prepared by the study interviewers and were then reviewed by a diagnostic committee of board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists or licensed psychologists. The diagnostic committee was blind to each subject’s ascertainment group and diagnoses were made for two points in time: lifetime and current (past month). The interviewers had been instructed to take extensive notes about the symptoms for each disorder. These notes and the structured interview data were reviewed by the diagnostic committee so that the committee could make a best-estimate diagnosis, as described by Leckman et al. 21. Definite diagnoses were assigned to subjects who met all diagnostic criteria. Diagnoses were considered definite only if a consensus was achieved that criteria were met to a degree that would be considered clinically meaningful. By “clinically meaningful,” we mean that the data collected from the structured interview indicated that the diagnosis should be a clinical concern because of the nature of the symptoms, the associated impairment, and the coherence of the clinical picture.

We computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having experienced board-certified child and adult psychiatrists and licensed clinical psychologists diagnose subjects from audiotaped interviews. On the basis of 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was 0.98. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses were ADHD (0.88), conduct disorder (1.00), major depression (1.00), mania (0.95), separation anxiety (1.00), agoraphobia (1.00), panic (0.95), substance use disorder (1.00), and tics/Tourette’s disorder (0.89).

Statistical Analysis

We conducted analyses on probands who had a current diagnosis of ADHD. Categorical data were analyzed using Pearson’s X2 test (?) and when necessary, Fisher’s exact test. T-tests and one-way analysis of variance were used to analyze continuous variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum and the Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to analyze continuous variables that were not normally distributed. An alpha-level of 0.05 was used to assert statistical significance; all statistical tests were two-tailed. We calculated all statistics using STATA 10.0.

Results

In this sample, there were 107 ADHD adults of which 49% (N=52) were male and 51% (N = 55) were female. The mean age of the sample was 37±10.4 years. Men were significantly younger than women (Men: 34, Women: 39; t=2.8, p<0.01). The mean SES of the sample was 2.0 ± 0.9 (Table 1). There were no differences in SES between sexes or across the subtypes of ADHD. This was a highly comorbid group of adults: 8% had no psychiatric comorbidity, 10% had a lifetime history of one comorbid psychiatric disorder, 14% had two, 15% had three, and 53% had four or more psychiatric comorbidities. When asked about the level of overall impairment related directly to their ADHD symptoms in the past, 40% (N=43) of our ADHD sample endorsed severe impairment, 53% (N=57) moderate impairment, and 7% (N=7) mild impairment. Likewise, when asked about the level of impairment caused by their ADHD symptoms within the past month, 23% (N=24) endorsed severe impairment, 51% (N=54) moderate impairment, and 26% (N=28) mild impairment.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Adults with ADHD (N = 107)

| Mean | SD ± | |

|---|---|---|

| SES1 | 2 | .90 |

| Age | 37 | 10.4 |

| N | % | |

| Gender Males |

52 | 49 |

| Current Subtypes Inattentive Hyperactive Combined |

33 8 66 |

31 7 62 |

N = 98 (9 missing values)

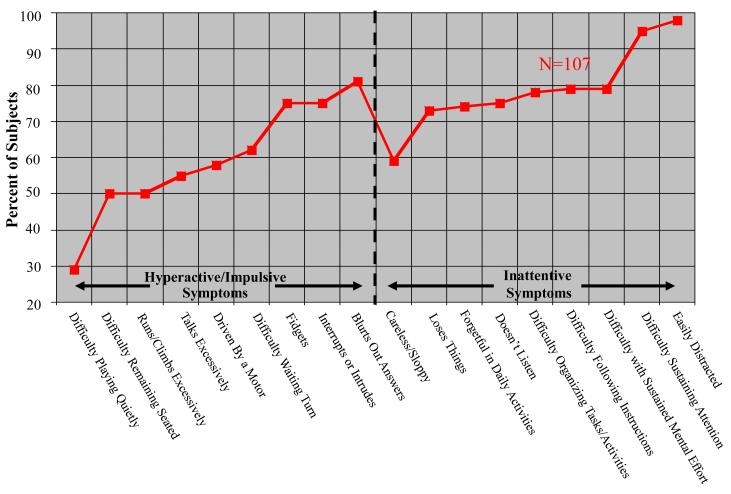

When examining specific DSM-IV ADHD symptoms, inattentive symptoms were more frequently endorsed overall than hyperactive symptoms. The most commonly reported inattentive symptoms were: “being easily distracted”, “difficulty sustaining attention,” and “difficulty with sustained mental effort.” The most commonly reported hyperactive symptoms were: “blurts out answers”, “interrupts or intrudes,” and “fidgets”. Sixty-two percent (N=66) of adults had the combined subtype, 31% (N=33) had the inattentive subtype, and 7% (N=8) had the hyperactive-impulsive subtype. There were no differences between males and females in the total number of endorsed inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms. However, when examining each symptom individually, females were significantly more likely to endorse the inattentive symptom of loses things (χ=7.5, p<0.01). When the sample was split into two groups at the median age of 38 years, there were no differences between age groups in the total number or type of endorsed inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms.

Adults with a combined type of ADHD had significantly higher rates of lifetime conduct disorder, bipolar disorder, and psychosis compared to those with the inattentive and the hyperactive-impulsive subtypes (Table 2). From the post hoc analysis, we determined that adults with the combined type had a significantly greater prevalence of conduct disorder and bipolar disorder when only compared to the inattentive subtype. In regards to academic functioning, there were no significant differences in the number of individuals who repeated a grade, took a special class, and had extra help across the ADHD subtypes.

Table 2.

| Combined Type N= 66 (62% of the sample) |

Inattentive Type Only N=33 (31% of the sample) |

Hyperactive Type Only N=8 (7 % of the sample) |

Overall Significance |

P-value Combined vs. Innatentive |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disorders | N (%) | N(%) | N(%) | df = 2 | |

| Disruptive Disorders | |||||

| Conduct Disorder | 24 (36)a | 4 (12) | 0 (0) | 0.006 | 0.01 |

| Antisocial Disorder | 15 (23) | 2 (6) | 1 (12) | 0.081 | 0.04 |

| Oppositional Disorder | 30 (45) | 9 (27) | 2 (25) | 0.177 | 0.08 |

| Mood Disorders | |||||

| Major Depression (Severe) | 28 (62) | 4 (29) | 3 (43) | 0.060 | 0.03 |

| Dysthymia | 18 (27) | 5 (15) | 0 (0) | 0.144 | 0.18 |

| Bipolar(combined I & II) | 15 (23)a | 2 (6)b | 3 (15) | 0.031 | 0.04 |

| Psychosis | 10 (15) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) | 0.017 | 0.01 |

| Anxiety Disorders | |||||

| Multiple (>2) Anxiety Disorders | 28 (42) | 9 (27) | 3 (38) | 0.393 | 0.14 |

| Panic Disorder | 18 (27) | 4 (12) | 1 (13) | 0.198 | 0.09 |

| Simple Phobia | 13 (20) | 7 (21) | 4 (50) | 0.182 | 0.86 |

| Social Phobia | 26 (39) | 9 (27) | 3 (38) | 0.476 | 0.23 |

| Separation Anxiety | 8 (12) | 2 (6) | 1 (13) | 0.590 | 0.29 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 19 (29) | 6 (18) | 2 (25) | 0.490 | 0.25 |

| Agoraphobia | 13 (20) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.269 | 0.18 |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 9 (14) | 3 (9) | 1 (13) | 0.896 | 0.38 |

| Avoidance Disorder | 3 (5) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | 0.59 |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder | 9 (14) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.701 | 0.38 |

| Substance Use Disorders | |||||

| Alcohol Abuse | 41 (62) | 16 (48) | 4 (50) | 0.370 | 0.20 |

| Alcohol Dependence | 21 (32) | 10 (30) | 3 (38) | 0.897 | 0.88 |

| Substance Abuse | 30 (46) | 13 (40) | 4 (50) | 0.782 | 0.57 |

| Substance Dependence | 20 (30) | 4 (12) | 3 (38) | 0.071 | 0.047 |

| Any Abuse or Dependence | 48 (73) | 23 (70) | 6 (75) | 0.941 | 0.75 |

| Eating Disorders | |||||

| Anorexia | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 0.149 | 0.44 |

| Bulimia | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (13) | 0.348 | 0.71 |

| Other | |||||

| Repeated Grade | 15 (23%) | 5 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0.277 | 0.38 |

| Special Class | 11 (17%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (25%) | 0.343 | 0.24 |

| Extra Help | 34 (52%) | 14 (42%) | 4 (50%) | 0.684 | 0.39 |

p<0.05 vs. Inattentive Subtype only by Pearson’s Chi Squared

p<0.05 vs. Hyperactive Subtype only by Pearson’s Chi Squared

We further examined our data to determine whether sex was related to psychiatric comorbidity. Men had significantly higher lifetime rates of comorbid conduct disorder and alcohol abuse (p’s<0.01), while women had significantly higher rates of comorbid dysthymia, panic disorder (p’s<0.05), agoraphobia, simple phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder (p’s<0.01).

Discussion

The results of the current study indicate that clinically referred adults with ADHD have prominent symptoms of inattention. Using DSM-IV criteria, 93% of ADHD adults had either the predominately inattentive or combined subtypes-indicative of prominent behavioral symptoms of inattention in adults. Psychiatric comorbidity was more commonly found in subjects with hyperactivity-impulsivity as part of their adult presentation.

Similar to our results, studies of the prevalence of DSM-IV subtypes in clinically referred ADHD children and adolescents in the DSM-IV field trials 22, show that the combined type is the most prevalent type of ADHD (66%) followed by the inattentive (33%), and the hyperactive-impulsive types (8%). Moreover, our results are similar to community-based studies in children reporting high rates of the inattentive subtype (5.4%) followed by the combined (3.6%) and hyperactive-impulsive (2.4%) types 23. In our sample, the overwhelming majority of ADHD adults endorsed prominent inattentive symptoms that were subsumed in either the inattentive or combined subtypes (93%). Our findings are consistent with aggregate studies in which the majority of children and adolescents had criteria for a subtype of ADHD with inattention 22. That inattentive symptoms predominate also support findings of impaired neuropsychological functioning, working memory, and executive functioning in ADHD adults 24.

The high rates of symptoms of inattention relative to hyperactivity/impulsivity are consistent with prospectively derived data in clinical and epidemiologically based samples of ADHD children, adolescents, and young adults in which decreases in the hyperactive and impulsive symptom clusters compared to the inattentive clusters were evident over time 8-10, 25-28.

We found that psychiatric comorbidity was more common in context to the combined and inattentive subtypes. It may be that psychiatric comorbidity is a marker of more severe ADHD as exemplified by more symptoms reflected in the combined subtype 29. Of interest, high rates of psychiatric comorbidity have been reported in adults with ADHD 6, 30, 31. Psychiatric comorbidity has also been shown to be associated with more persistent ADHD 13 and with prominent hyperactive/impulsive symptoms in adults with ADHD 32. More specifically, in the current study adults with a combined type of ADHD had significantly higher rates of lifetime conduct disorder, bipolar disorder, and psychosis compared to those with the inattentive subtype mirroring findings from a separate dataset showing more hyperactivity and impulsivity in adults with ADHD who had comorbid BPD relative to those without BPD ADHD 32.

Given this sample was largely derived from clinical referral, and because both clinically and epidemiologically derived samples of adults with ADHD have been shown to have high rates of co-occurring psychopathology 6, 30, 31, it is difficult to disentangle whether higher specific symptom clusters as well as higher symptom counts are associated with comorbidity, or if comorbidity skews symptom counts. Further analysis should be done on specific endorsed symptoms in longitudinal studies. These aggregate data suggest the need to carefully examine adults with more pronounced symptoms of ADHD for other psychiatric comorbidity. Moreover, psychiatric comorbidity with ADHD may predict a more persistent form of ADHD 32.

Interestingly, we found no sex differences in ADHD symptoms. In the sample with equal sex distribution, both sexes had high rates of attentional dysfunction relative to hyperactive/impulsivity. Moreover, similar to previous reports in adults 33, we found that males with ADHD had higher lifetime comorbidity with conduct disorder and alcohol abuse relative to females with ADHD. Conversely, females had higher rates of comorbid dysthymia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, simple phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder compared to males. These findings are consistent with data derived from longitudinal studies of girls growing up, which highlight more similarities than dissimilarities in the core ADHD and general and cognitive functioning between the sexes34. However, notable differences in specific comorbidities between the sexes remain.

The results of this study need to be tempered against their substantial limitations. The findings are based in part on observations from both a non-referred and clinically referred population and, therefore, may not generalize to all adults with ADHD. Also, because we only assessed adults who met 6 out of the 9 child-based ADHD diagnostic criteria, our sample represents a more severe group of ADHD adults and may not generalize to all adults with ADHD. The symptoms reported by these adults may not have been entirely accurate given the retrospective recall required of past symptoms. However, previous studies have documented the validity of using retrospective recall in the diagnosis of ADHD adults 16, 18, 35, 36.

Despite these limitations, findings from the current study support previous work with separate samples that the vast majority of adults with ADHD present prominent symptoms of inattention, independent of sex. Compared to adults with the inattentive subtype of ADHD, those with the combined subtype had higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity. Given the high prevalence of ADHD occurring in mental health and substance abuse domains, more emphasis on the inattentive aspects of ADHD need to be highlighted when making the diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Presenting DSM-IV Symptoms in Adults with ADHD

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Funding for this study was RO1 DA12945 (TW) and K24 DA016264 (TW)

Footnotes

Disclosures for authors attached.

References

- 1.Weiss G, Hechtman L, Milroy T, Perlman T. Psychiatric status of hyperactives as adults: A controlled prospective 15 year followup of 63 hyperactive children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1985;24:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilens T, Faraone SV, Biederman J. Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(5):619–623. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mick E, Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T. The course and outcome of ADHD. Primary Psychiatry. 2004;11(7):42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alpert J, Maddocks A, Nierenberg A, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in childhood among adults with major depression. Psychiatry Research. 1996;62:213–219. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schubiner H, Tzelepis A, Milberger S, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder among substance abusers. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(4):244–251. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–723. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, Hwang I, LaBrie R, et al. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2008 Sep;38(9):1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biederman J, Faraone S, Mick E. Age dependent decline of ADHD symptoms revisited: Impact of remission definition and symptom subtype. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:816–817. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achenbach TM, Howell CT, McConaughy SH, Stanger C. Six-year predictors of problems in a national sample of children and youth: I. Cross-informant syndromes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(3):336–347. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart EL, Lahey BB, Loeber R, Applegate B, Frick PJ. Developmental change in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in boys: A four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23(6):729–749. doi: 10.1007/BF01447474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gammon GD, Brown TE. Fluoxetine and methylphenidate in combination for treatment of attention deficit disorder and comorbid depressive disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 1993;3(1):1–10. doi: 10.1089/cap.1993.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millstein RB, Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ. Presenting ADHD symptoms and subtypes in clincially referred adults with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 1997;2(3):159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, et al. Predictors of persistence and remission of ADHD into adolescence: Results from a four-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(3):343–351. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199603000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinshaw SP. Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Background characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive, and social functioning, and parenting practices. J Consult Clin Psych. 2002;70(5):1086–1098. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E, et al. A family study of psychiatric comorbidity in girls and boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50:586–592. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adler L, Cohen J. Diagnosis and evaluation of adults with ADHD. In: Spencer T, editor. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Saunders Press; Philadelphia, P.A.: 2004. pp. 187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wender P. The Hyperactive Child, Adolescent, and Adult: Attention Deficit Disorder Through the Lifespan. Oxford University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein MA, Sandoval R, Szumowski E, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the Wender Utah rating scale: Reliability and factor structure for men and women. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1995;31:423–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, D.C.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ambrosini PJ. Historical development and present status of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):49–58. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson D, Belanger A, Weissman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: A methodological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lahey B, Applegate B, Barkley R, et al. DSM-IV field trials for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1163–1172. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolraich M, Hannah J, Pinnock T, Baumgaetel A, Brown J. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in a county-wide sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(3):319–324. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199603000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seidman L, Doyle A, Fried R, Valera E, Crum K, Matthews L. Neuropsychological functioning in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactiity disorder. In: Spencer T, editor. Adult ADHD, Psychiatric Clinics of North America: Elsevier Science. 2004. pp. 261–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy K, Barkley RA. Prevalence of DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD in adult licensed drivers: Implications for clinical diagnosis. Journal of Attention Disorders. 1996;1(3):147–161. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:565–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190067007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy F, Hay D, McStephen M, Wood C, Waldman I. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A category or a continuum? Genetic analysis of a large-scale twin study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(6):737–744. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faraone S, Biederman J, Mick E. The Age Dependent Decline Of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analysis Of Follow-Up Studies. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(2):159–165. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500471X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Friedman D. Validity of DSM-IV subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a family study perspective. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(3):300–307. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200003000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGough JJ, Smalley SL, McCracken JT, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings from multiplex families. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;162(9):1621–1627. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sobanski E, Bruggemann D, Alm B, et al. Subtype differences in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with regard to ADHD-symptoms, psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial adjustment. Eur Psychiatry. 2008 Mar;23(2):142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilens T, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Gunawardene S, Wong J, Monuteaux M. Can Adults with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder be Distinguished from those with Comorbid Bipolar Disorder: Findings from a Sample of Clinically Referred Adults. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer TJ, Wilens TE, Mick EA, Lapey K. Gender differences in a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Research. 1994;53:13–29. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, et al. Influence of gender on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children referred to a psychiatric clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(1):36–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah rating scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:885–890. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adler LA, Faraone SV, Spencer TJ, et al. The reliability and validity of self- and investigator ratings of ADHD in adults. J Atten Disord. 2008 May;11(6):711–719. doi: 10.1177/1087054707308503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.