Abstract

Paying taxes can be considered a contribution to the welfare of a society. But even though tax payments are redistributed to citizens in the form of public goods and services, taxpayers often do not perceive many benefits from paying taxes. Information campaigns about the use of taxes for financing public goods and services could increase taxpayers’ understanding of the importance of taxes, strengthen their perception of fiscal exchange and consequently also increase tax compliance. Two studies examined how fit between framing of information and taxpayers’ regulatory focus affects perceived fiscal exchange and tax compliance. Taxpayers should perceive the exchange between tax payments and provision of public goods and services as higher if information framing suits their regulatory focus. Study 1 supported this hypothesis for induced regulatory focus. Study 2 replicated the findings for chronic regulatory focus and further demonstrated that regulatory fit also affects tax compliance. The results provide further evidence for findings from previous studies concerning regulatory fit effects on tax attitudes and extend these findings to a context with low tax morale.

Keywords: Regulatory fit, Fiscal exchange, Tax compliance

Taxpayers often perceive that there is little return for the taxes they pay. In one study (Kirchler, 1997), respondents stated that the perceived utility from public goods and services is lower than the desired utility for all 12 areas of expenditure (education, public health, etc.) listed. Such perceived imbalance in fiscal exchange can contribute to reduced tax compliance (Kirchler, 2007).

In order to increase tax compliance, different measures can be adopted. If the evasion rate is high, a deterrence policy could be a suitable strategy to promote taxpaying. Yet, apart from trying to promote tax compliance by severe controls which center on increasing the extrinsic motivation to pay taxes, it may also be important to change people’s attitudes toward paying taxes and to increase their trust in the tax authorities, i.e., to promote the intrinsic motivation for taxpaying (e.g., Andreoni et al., 1998; Feld and Frey, 2006; Kirchler et al., 2008; Torgler, 2003a). One reason why the intrinsic motivation to pay taxes can be low is that taxpayers blame the government for tax rates which are perceived as too high and claim that their share in public goods and services is too small (Kirchler and Maciejovsky, 2002). If taxpayers, instead, perceive that their preferences are adequately represented and they are supplied with public goods and services, the willingness to pay taxes rises (Alm and Torgler, 2006). Indeed, the perception of fair fiscal exchange has been shown to be one of the most relevant determinants of tax compliance (e.g., Wenzel, 2002; Hofmann et al., 2008).

Perceived exchange fairness can refer to three levels. First, horizontal fairness is concerned with the distribution of benefits and costs within a taxpayer’s income group. Second, vertical fairness is concerned with the distribution of benefits and costs across different income groups. Lastly, exchange fairness relates to the ratio between a taxpayer’s contributions and the provision of public goods and services by the government (cf. Wenzel, 2002; Kirchler, 2007). In the present research, we focus on the third aspect, specifically on the use of taxes for financing such public goods and services that are of relevance for most taxpayers as for example social welfare, education, transportation, matters of public interest, public tasks, infrastructure, social security and public health (cf. Kirchler, 1997).

One possible way to strengthen the perception of a fair fiscal exchange and thereby to encourage the intrinsic motivation for taxpaying are information campaigns that inform citizens about taxes, governmental spending policy and the provision of public goods and services. There is some evidence that information campaigns can have a positive effect on tax compliance (e.g., Hasseldine and Hite, 2003; McGraw and Scholz, 1988; Roberts, 1994; Taylor and Wenzel, 2001; White et al., 1990). For example, Roberts (1994) showed that taxpayers’ attitudes about fairness and compliance were more positive after watching short announcements transmitted via TV.

It is known from persuasion and advertising research that persuasive messages are particularly effective if the content of a message suits the recipients’ regulatory focus (e.g., Cesario et al., 2004; Evans and Petty, 2003; Florack and Scarabis, 2006; Pham and Avnet, 2004; Spiegel et al., 2004). This means that whether a piece of information is perceived as more or less convincing can depend on the motivational orientation it addresses.

The aim of the present research is to provide further evidence for a greater effectiveness of information campaigns concerning tax issues if the content of the latter and the recipients’ regulatory orientation are compatible with each other.

1. Promotion goals vs. prevention goals and regulatory fit

Regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997, 1998) proposes that people can pursue two distinct goals during self-regulation: promotion goals and prevention goals. Individuals with a promotion goal orientation are concerned with approaching desired end-states and fulfilling self-regulatory needs as advancement and growth. Individuals with a prevention goal orientation, instead, are concerned with avoiding undesired end-states and fulfilling self-regulatory needs as protection and safety. Consequently, promotion-focused individuals are sensitive to the presence or absence of positive outcomes (or gains vs. non-gains) and prevention-focused individuals are sensitive to the presence or absence of negative outcomes (or losses vs. non-losses). Whereas striving for ideals (i.e., hopes, wishes and aspirations) by using eager strategies determines goal achievement under a promotion focus, accomplishing oughts (i.e., duties, obligations and responsibilities) by using vigilant strategies determines goal achievement under a prevention focus (Higgins, 1997, 1998; see also Higgins and Spiegel, 2004).

Regulatory focus can both vary across individuals and across situations. Whereas chronic regulatory focus establishes through socialization (e.g., Higgins, 1997) or culture (e.g., Lee et al., 2000), situational regulatory focus can be induced for example by activating a person’s ideals or oughts (e.g., Freitas et al., 2002; Liberman et al., 1999; Pham and Avnet, 2004).

Regulatory fit theory (Higgins, 2000, 2002) posits that motivational strength is enhanced when the manner in which people pursue a goal sustains their regulatory orientation. The same desired end-state, e.g., tax compliance, can be described as being congruent with either a promotion or a prevention goal, i.e., either by emphasizing an approach motivation: “People should pay taxes in order to obtain well-functioning public services.”, or by emphasizing an avoidance motivation: “People should pay taxes in order to avoid malfunctioning public services.” (cf. Higgins, 1997).

Several studies have provided evidence that commercial as well as non-commercial advertisements are particularly effective under regulatory fit, i.e., if the content of a persuasive message corresponds to the recipients’ goal orientation (e.g., Aaker and Lee, 2001; Cesario et al., 2004; Evans and Petty, 2003; Florack and Scarabis, 2006; Pham and Avnet, 2004; Spiegel et al., 2004). For example, Florack and Scarabis (2006) found that consumers preferred a product more strongly when the claim used in an advertisement for the product was compatible with their regulatory focus. Cesario et al. (2004) showed that people more strongly approved a new education policy when the framing of a message in favor of the policy corresponded to their regulatory focus (for a similar finding, see Camacho et al., 2003).

First evidence for a positive influence of regulatory fit in information campaigns concerning tax issues was provided by Holler et al. (2008). These authors made taxpayers read a text which informed them about which portion of the tax revenues was used by the government for financing different public goods and services. They showed that such an informative text influences the willingness to pay taxes more strongly, if the framing of the text is congruent with the individual regulatory goal orientation.

The present research aimed at replicating the findings by Holler et al. by using a different dependent measure. Holler et al. (2008) provided participants with the exact data concerning fiscal exchange, i.e., which amount of the tax revenues is redistributed to the taxpayers in the form of public goods and services, and then examined the effect of regulatory fit on tax compliance. In the present studies, instead, participants’ attention was drawn to the fact that specific public goods and services are financed by tax revenues and they were then asked to estimate the rate of fiscal exchange themselves. As we wanted to test the general effect of an information campaign, the text focused on public goods and services that have been shown to be relevant to most taxpayers (e.g., public health, education and infrastructure, cf. Kirchler, 1997). It was assumed that fiscal exchange would be estimated as higher if the goal-framing of an informative text suits the recipient’s predominant regulatory focus. The higher taxpayers perceive the fiscal exchange provided by the government the stronger also their willingness to pay tax should be.

The present research further aimed at extending the previous findings to a different context. The studies were conducted in Italy, a country where tax morale and compliance are clearly lower in comparison to Austria, where the study by Holler et al. was conducted. Indeed, it has been shown by several studies using both survey data (e.g., Alm and Torgler, 2006; Schneider, 2005) and experimental designs (e.g., Lewis et al., 2009) that tax evasion in Italy is higher than in other countries. For example, a comparison between 21 OECD countries by Schneider (2005) showed that Italy is among the three countries where tax evasion is most common, whereas Austria is among the three countries with the lowest tax evasion rate. The finding that information campaigns can enhance tax compliance when taxpayers’ willingness to comply is already quite pronounced is very plausible and clear. The question is whether such campaigns have an effect as well when the general willingness to pay tax is low. The usefulness of different framing of information when planning information campaigns can be considered as particularly high if the influence of regulatory fit is also shown for a context with low tax morale.

2. Study 1: regulatory fit and perceived exchange between tax payments and provision of public goods and services

This study examines how fit between induced regulatory focus and goal-framing influences perceived fiscal exchange. The Italian Ministry of Finances (Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze, 2005) on its homepage provides information about the tax revenues collected by the state, but it does not provide information about which amount is spent for public goods and services. Therefore, citizens have no clear information about the percentage of taxes spent for the provision of public goods and services, and it is of relevance to investigate what ratio people think is spent by the government for the sake of citizens. As mentioned above, perceived fiscal exchange between taxpayers and government is an important factor which is assumed to influence tax compliance, along with perceptions of fairness and trust in institutions (cf. Alm and Torgler, 2006; Braithwaite and Ahmed, 2005; Kirchler, 2007; Torgler, 2003a).

It is expected that regulatory fit affects perceived fiscal exchange. Regulatory focus was experimentally induced through a regulatory focus priming task (Freitas et al., 2002). We hypothesize that an induced promotion focus is related to higher perceived fiscal exchange if a text about the use of tax payments for public goods and services concentrates on positive outcomes, emphasizing advantages of financing public goods and services through taxes. For an induced prevention focus, it is assumed that perceived fiscal exchange is higher if the text concentrates on negative outcomes, emphasizing disadvantages of not being able to finance public goods and services because of low tax revenues.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

Eighty working students, 46 men and 34 women, participated in the study on a voluntary basis. Their mean age was 33.86 years (SD = 9.59). The sample consisted of 65 employees and 14 freelance professionals (1 missing). Data were collected at the Sapienza University of Rome during evening courses for working students at the Faculty of Political Sciences. Participants took about 15 min to fill out the questionnaire.

3.2. Design

The design was a 2 by 2 design with experimentally induced regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) as independent variables. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions: 37 participants were assigned to the promotion condition and 43 to the prevention condition. Forty participants read the positively framed text and 40 read the negatively framed text. All participants filled in a questionnaire on tax issues.

3.2.1. Material and procedure

The questionnaire consisted of an introduction, a regulatory focus priming, a positively or negatively framed text concerning the use of taxes to finance public goods and services and an item measuring perceived fiscal exchange. Further, it included a scale measuring tax morale and questions regarding socio-demographic information.

To make the priming task and the other tasks seem unrelated, participants were told that we were conducting two studies: a “study on personal memories” and a “study on economic issues”. To make this information believable, participants received the regulatory focus priming and the other parts of the questionnaire in two separate envelopes.

Regulatory focus priming

In order to induce either a promotion or prevention focus, a procedure used by Freitas et al. (2002) was applied. This procedure has been used in several studies to induce regulatory focus (e.g., Higgins et al., 1994; Idson et al., 2004; Liberman et al., 1999) and can therefore be considered a valid manipulation of regulatory focus. Participants were asked to write a short essay describing how their personal standards had changed over time comparing the present to when they were younger. The personal standards were described in the instruction either as ideals (priming promotion focus) or oughts (priming prevention focus). The instruction was as follows, with the phrases in italics being used in the ideal condition (i.e., primed promotion focus), the phrases in parentheses in the ought condition (i.e., primed prevention focus, cf. Freitas et al., 2002).

“Describe how your hopes and aspirations (duties and obligations) are different now from what they were when you were growing up. In other words, what accomplishments would you ideally like (think you ought) to meet at this point of your life? What accomplishments (responsibilities) did you ideally want to meet when you were a child?”

Information about the use of taxes

After having written the short essay, participants opened the second envelope and read the same small text on the necessity of paying taxes for the benefit of the society in general. The text did not contain information about the actual amount of the tax revenues used for public goods and services. It emphasized instead that tax revenues are an important financial contribution for the functioning and the support of different public goods and services. Then participants either read positively or negatively framed information about the state’s provision of public goods and services for the health system, education, public transport and traffic, public safety and civil protection, expenditures on arts and cultural activities, as well as social security. The text for positive goal-framing highlighted the benefits for everyone when the number of compliant taxpayers is high, whereas the text for negative goal-framing highlighted the deficiencies for everyone when the number of compliant taxpayers is low. In general, the text focused on different types of public goods and services provided by the state that should be relevant for most taxpayers (Kirchler, 1997, 2007).

Perceived fiscal exchange

Then, participants read the following item measuring perceived fiscal exchange: “According to you, which percentage of the tax revenues is used by the Italian state for the financing of public goods and services?” The response mode was open-ended and participants answered by indicating the percentage themselves. The higher this perceived percentage, the more positive is the view of respondents regarding the return on their taxes, and the more positive is their evaluation of fiscal exchange.

Tax morale

Finally, participants filled out a tax morale scale consisting of 16 items adapted from Braithwaite and Ahmed (2005). As described above, tax morale in Italy generally is low. Yet, it seemed important to include a measure of tax morale as control variable in order to be able to take into account a possible variability in tax morale on an individual level. The scale measures the extent to which people express commitment to the tax system and the belief that taxpaying is socially responsible (Braithwaite and Ahmed, 2005, e.g., “Citizenship carries with it a duty to pay tax”). Participants’ responses were recorded on a six-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Reliability was satisfactory (α = .83; M = 4.48; SD = .69).

Socio-demographic data

After collecting socio-demographic data on gender, employment status and age, participants were thanked and debriefed.

4. Results

Overall, participants’ estimates of perceived fiscal exchange were not very high1 (M = 34.33%) and demonstrated a great variability (SD = 20.07%). To test the hypothesis, a 2 by 2 ANOVA was computed with the regulatory focus priming (promotion vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) as independent variables and perceived fiscal exchange as dependent measure.

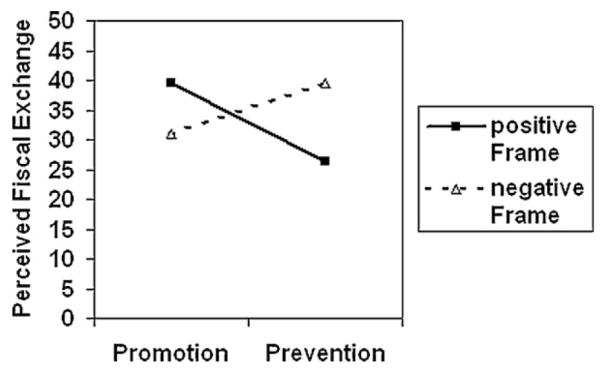

Consistent with our hypothesis, a significant regulatory focus by goal-framing interaction effect on perceived fiscal exchange was obtained (F (1,76) = 6.16; p = .02; η2 = .08, see Fig. 1), with main effects of regulatory focus and goal-framing non-significant (both Fs < 1.0).

Fig. 1.

Interaction effect of induced regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) on perceived fiscal exchange.

Perceived fiscal exchange was significantly higher under conditions of regulatory fit (M = 39.58, SD = 22.62) than under conditions of non-fit (M = 28.81, SD = 15.40; p = .02). People under induced promotion focus assumed fiscal exchange to be higher when the text emphasized the beneficial consequences of taxpaying for the citizens (M = 39.58, SD = 21.70) compared to when it emphasized the negative consequences of low tax revenues (M = 31.01, SD = 16.36). People under induced prevention focus, instead, estimated fiscal exchange to be higher when the text concentrated on the disadvantages for the citizens if taxes are not paid (M = 39.57, SD = 24.40), compared to when it concentrated on the advantages if taxes are paid (M = 26.24, SD = 14.23).

In a second analysis,2 gender, employment status, age and tax morale were included as covariates. Neither gender (F (1,69) = 0.32; p = .58; η2 < .01), nor age (F (1,69) = 0.20; p = .66; η2 < .01), nor employment status (F (1,69) = 0.62; p = .43; η2 < .01) showed significant effects. Tax morale, instead, was a significant covariate (F (1,69) = 5.44; p = .02; η2 = .07). A positive correlation between perceived fiscal exchange and tax morale (r = .26; p = .02) indicates that higher tax morale was related to higher perceived fiscal exchange. The effects of the experimental variables remained unchanged. The regulatory focus by goal-framing interaction effect on perceived fiscal exchange was significant (F (1,69) = 6.30; p = .01; η2 = .08), with main effects of regulatory focus and goal-framing non-significant (both Fs < 1.0).

5. Discussion

Results indicate that taxpayers assume fiscal exchange to be higher when information framing is compatible with their induced regulatory focus. Promotion-primed participants’ estimates of fiscal exchange provided by the government increased after reading a text about the use of tax revenues which emphasized the positive consequences of adequate tax payments. The same was true for prevention-primed participants when the text concentrated on the negative consequences of inadequate tax payments. In other words, participants estimated the percentage of tax payments returned to them in form of public goods and services as higher under regulatory fit.

Further, it was found that a higher perception of fiscal exchange was also related to a stronger intrinsic willingness to pay tax (tax morale). It was important for our hypothesis that in the analysis of covariance the regulatory focus by goal-framing interaction effect remained significant when tax morale was included in the analysis as covariate. Thus, it can be concluded that the influence of regulatory fit on perceived fiscal exchange occurs independently of tax morale, i.e., that it is valid for both people with high and low intrinsic motivation to pay tax.

Study 1 showed that regulatory fit influences the perception of fiscal exchange, but it did not address the question whether regulatory fit also enhances tax compliance (cf. Holler et al., 2008). Therefore, a second study was conducted which not only aimed at replicating the findings of the present study, but also assessed possible effects on tax compliance. As mentioned previously, it seems of relevance to replicate the findings by Holler et al. (2008) in a context were tax morale is generally low.

Whereas in Study 1 regulatory focus was induced by a priming procedure, Study 2 investigates effects of regulatory fit on perceived fiscal exchange and willingness to pay tax with regulatory focus as a personal disposition.

6. Study 2: regulatory fit, perceived fiscal exchange and tax compliance

In the second study, we examine the influence of chronic regulatory focus and goal-framing on perceived fiscal exchange and intended tax compliance. We assume that fit between framing of information and participants’ regulatory focus, in comparison to non-fit, does not only lead to higher perceived fiscal exchange as shown in Study 1, but also to higher tax compliance (cf. Holler et al., 2008). When reading a tax scenario, taxpayers with promotion focus should be more willing to pay their taxes honestly after reading information concentrating on the presence of functioning services when taxes are paid. Taxpayers with prevention focus, instead, should indicate being more honest after having read a text concentrating on the absence of functioning services when taxes are not paid.

7. Method

7.1.1. Participants

Eighty-three taxpayers (46 men, 37 women) participated in this study. Their mean age was 39.63 years (SD = 11.35). The sample consisted of 80 employees, 3 participants were freelance professionals. Data was collected in Rome, Italy, at the workplaces of the participants.

7.1.2. Design

A 2 by 2 between-subjects design with regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) as independent variables was set up to investigate effects on perceived fiscal exchange and tax compliance as dependent variables. Participants were randomly assigned to framing conditions: 42 participants read the positively framed text and 41 read the negatively framed text. All participants filled in a questionnaire on tax issues. Regulatory focus of participants was assessed by the Regulatory Focus Questionnaire (Higgins et al., 2001) which yielded data to split the sample into a group of 40 participants with predominant promotion focus and a group of 43 participants with predominant prevention focus.

7.1.3. Material and procedure

Participants filled out a questionnaire which consisted of a short introduction, the Regulatory Focus Questionnaire, the same information campaign about public income and spending as well as provision of public goods and services as in Study 1, an item measuring perceived fiscal exchange, a tax filing scenario, a scale assessing tax compliance, the same scale measuring tax morale as in Study 1 and the same questions on socio-demographic characteristics as in Study 1. It took about 15 min to fill out the questionnaire.

Regulatory focus

The Regulatory Focus Questionnaire (RFQ) by Higgins et al. (2001) was used to assess participants’ promotion and prevention orientation. This 11-item scale is composed of two subscales with six items measuring promotion focus (e.g., “I feel like I have made progress toward being successful in my life.”) and five items measuring prevention focus (e.g., “Not being careful enough has gotten me into trouble at times”). A factor analysis with a two-factor solution indicated that one promotion item loaded on both factors and had to be excluded. The final promotion score was computed as an average of five items (Cronbach Alpha = .47) and so was the prevention score (Cronbach Alpha = .51). There was no correlation between the two scores (r = −.01; p = .93). Participants were classified in terms of whether, compared to others, they were relatively more promotion-oriented or relatively more prevention-oriented based on a median split on the difference between their promotion score and their prevention score (for this procedure, see Higgins et al., 2001).

Information about the use of taxes

Next, participants read the same text as in Study 1 about how the state uses the tax revenues for the financing of public goods and services.

Perceived fiscal exchange

Then, participants read the same item measuring perceived fiscal exchange as in Study 1.

Tax compliance

In order to assess tax compliance, a scenario adopted from Holler et al. (2008) was used. Participants had to step into the shoes of an employed taxpayer who earned €4500 extra money in order to afford a new car. This extra money was subject to income tax. Participants had to decide whether to indicate the extra income on their tax file and pay taxes or not. They were given the exact figures of how much social insurance and income tax they would have to pay. It was also mentioned in the scenario that fines would be imposed on taxpayers convicted of cheating, yet, the risk of being caught was described as very low. Intended tax compliance was measured by asking how likely it was that they would indicate their extra income on their tax file and pay taxes honestly (answers were marked on a 10 cm long line with the poles labeled 0 = definitely sure not to indicate the extra income, and 100 = definitely sure to indicate the extra income. The graphic scale was used to reduce social desirability tendencies which are high in tax compliance measures).

Tax morale

Also in this study tax morale was assessed as control variable. Participants filled out the same tax morale scale as in Study 1 consisting of 16 items adapted from Braithwaite and Ahmed (2005). Reliability was satisfactory (α = .79; M = 4.67; SD = .57).

Socio-demographic data

Finally, after collecting socio-demographic data as gender, employment status and age, participants were thanked and debriefed.

8. Results

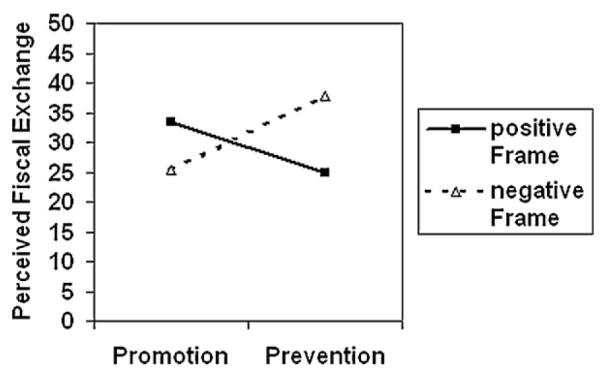

As in Study 1, participants’ estimates of perceived fiscal exchange were rather low (M = 30.84%) and demonstrated large variability (SD = 20.97%). A 2 by 2 multivariate ANOVA with chronic regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) as independent variables resulted – as predicted – in a significant interaction effect on perceived fiscal exchange (F (1,82) = 5.32; p = .02; η2 = .06) and on tax compliance (F (1,82) = 5.10; p = .03; η2 = .06). Main effects of regulatory focus and goal-framing were not significant (both Fs < 1.0).

As in Study 1, perceived fiscal exchange was significantly higher under conditions of regulatory fit (M = 35.66, SD = 24.28) than under conditions of non-fit (M = 25.13, SD = 15.55; p = .02). Participants with predominant promotion focus perceived fiscal exchange as higher when the text emphasized the beneficial consequences of taxpaying for the citizens (M = 33.41, SD = 23.50) compared to when it concentrated on the negative consequences of low tax revenues (M = 25.28, SD = 13.77). Participants with predominant prevention focus perceived fiscal exchange as higher when the framing of the text was negative (M = 37.82, SD = 25.34), compared to when it was positive (M = 24.99, SD = 15.58) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Interaction effect of chronic regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) on perceived fiscal exchange.

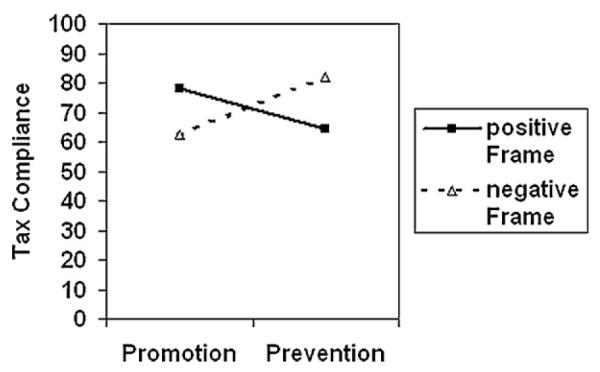

Analogously, tax compliance was significantly higher under conditions of regulatory fit (M = 80.07, SD = 29.37) than under conditions of non-fit (M = 63.35, SD = 37.25; p = .03). Participants with predominant promotion focus showed greater tax compliance when the text emphasized the beneficial consequences of taxpaying for the citizens (M = 77.91, SD = 28.72) compared to when it concentrated on the negative consequences of low tax revenues (M = 62.39, SD = 35.18). Participants with predominant prevention focus, instead, were more willing to declare the extra money when the framing of the text was negative (M = 82.13, SD = 30.48), compared to when it was positive (M = 64.21, SD = 39.91) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Interaction effect of chronic regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) and goal-framing (positive vs. negative) on tax compliance.

In a second analysis, gender, age and tax morale were included in the analysis as covariates. As in Study 1, tax morale was the only marginally significant covariate for perceived fiscal exchange as the dependent variable (F (1,75) = 3.73; p = .06; η2 = .05) and it was a significant covariate for tax compliance as the dependent variable (F (1,75) = 19.67; p < .01; η2 = .21). There was a marginally significant correlation between perceived fiscal exchange and tax morale (r = .21; p = .06), and a significant correlation between tax compliance and tax morale (r = .45; p < .01), indicating that, overall, higher tax morale was related to higher perceived fiscal exchange and to a greater willingness to pay taxes. For the experimental variables the same effects as in the previous analysis without covariates were obtained. The regulatory focus by goal-framing interaction effect on perceived fiscal exchange was significant (F (1,75) = 5.44; p = .02; η2 = .07), with non-significant main effects of regulatory focus and goal-framing (both Fs < 1.0). Also the regulatory focus by goal-framing interaction effect on tax compliance was significant (F (1,75) = 4.94; p = .03; η2 = .06), with non-significant main effects of regulatory focus and goal-framing (both Fs < 1.0).

9. Discussion

In the second study, the interaction effect of regulatory focus by framing on perceived fiscal exchange obtained in Study 1 was replicated for chronic regulatory focus. Further and in line with a previous study by Holler et al. (2008) it was shown that compatibility between regulatory focus and framing also affects tax compliance.

Taxpayers with a promotion focus estimate fiscal exchange as higher and are more willing to comply when they are provided with information that emphasizes the advantages if tax revenues received by the state are high enough. Taxpayers with a prevention focus, instead, perceive fiscal exchange as higher and are more compliant after reading a text referring to the disadvantages if tax revenues received by the state are too low.

The results also confirm the finding from Study 1 that the regulatory fit effect occurs independently of gender, age or tax morale. As in Study 1, in the analysis of covariance tax morale was found to be a significant covariate, but the interaction effect of regulatory focus and goal-framing remained significant. Therefore, it can be concluded that this effect occurred independently of tax morale.

10. Conclusions

In two studies, interaction effects between regulatory focus and goal-framing on perceived fiscal exchange and willingness to pay tax were found. According to the results, both information emphasizing positive consequences of tax compliance and information emphasizing negative consequences of tax evasion should be used in information campaigns aiming at promoting perceived fiscal exchange and tax compliance.

Our results are in line with those obtained by Holler et al. (2008) showing that regulatory fit not only affects tax compliance, but also influences perceived fiscal exchange. The two studies also suggest which kind of information could be used in campaigns trying to promote tax compliance. Whereas the informative text used by Holler et al. (2008) reported the exact figures of the fiscal exchange between taxpayers and government, the text used in the present studies only referred to the importance of the latter for financing different kinds of public services, and still the same pattern of results was found.

It is noteworthy that in the present studies perceived fiscal exchange and tax compliance were increased under regulatory fit even though the text contained only information about what kind of public goods and services are financed by tax revenues, but not about which sum of money is used for them. Thus, on the one hand, it seems that the mere information that the government provides public goods and services can influence the perception of fiscal exchange positively.

On the other hand, the low overall estimate of the percentage of tax payments redistributed as public goods and services – only between 30 and 35 per cent – in the present studies suggests that it seems actually to be very important to inform citizens not only about the kind of exchange they receive, but also about the exact figures.

The present studies further extend Holler et al.’s findings to a context which has been shown to differ in tax morale and compliance (e.g., Alm et al., 1995; Alm and Torgler, 2006; Gërxhani and Schram, 2006; Torgler, 2003b) with tax morale and compliance being lower in Italy compared to Austria. Cross-cultural studies on tax compliance normally try to discover differences in values, norms or attitudes that influence compliance. The present research and Holler et al.’s research, however, suggest a similarity between Austrian and Italian taxpayers. Congruency between the framing of an informative text and the recipients’ motivational orientation seems to affect taxpayers in both countries in the same way. Therefore, similar campaigns for promoting exchange fairness and tax compliance could be used for an international audience.

Further, running information campaigns concerning tax issues may be particularly important in a country where tax morale is low. By providing the exact figures about fiscal exchange the government could demonstrate transparency and thereby increase trust in tax authorities which is another important determinant of tax compliance. Generally, when tax compliance is low, it seems to be relevant not only to decrease tax evasion by using a deterrence policy, but also to promote a general acceptance of taxes in order to establish a new social norm.

In the present research we focused on fiscal exchange between the government and taxpayers concerning issues that are considered to be important by most taxpayers. We examined the effect of information campaigns that emphasize benefits for most taxpayers and focused on exchange fairness. But tax revenues are also used for financing specific groups that do not include all taxpayers or for issues that may be considered unpopular by some taxpayers (e.g., the financing of military and defense spending). Future research should address this topic and examine whether information campaigns can also help promoting tax compliance when issues as vertical fairness or the use of tax revenues for unpopular areas are concerned.

Footnotes

As mentioned above, the Italian Ministry of Finances (Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze, 2005) does not provide information about the exact percentage, but in other countries (e.g., Austria, s. Bundesministerum für Finanzen, 2005) about 50 percent of the tax revenues are redistributed to the citizens in form of public goods and services.

In order to control for the possible influence of further variables on the dependent variable, a commonly used method of analysis in psychological research is the analysis of covariance. It allows testing which effect the independent variables have after the effect of the covariate has been partialled out. The results indicate the effect for an assumed condition in which participants’ values on the covariate are equal across groups. If the covariate is significant and the previously found effect reduces to non-significance this means that the effect did not occur due to the independent variable(s), but due to the covariate.

References

- Aaker JL, Lee AY. “I” seek pleasures and “we” avoid pains: the role of self-regulatory goals in information processing and persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research. 2001;28:33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Alm J, Sanchez I, deJuan A. Economic and noneconomic factors in tax compliance. Kyklos. 1995;48(1):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Alm J, Torgler B. Culture differences and tax morale in the United States and Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2006;27:224–246. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni J, Erard B, Feinstein JS. Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature. 1998;36(2):818–860. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite V, Ahmed E. A threat to tax morale: the case of Australian higher education policy. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2005;26:523–540. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Finanzen Budget 2005. [accessed 25.11.08]. 2005. < http://www.bmf.gv.at/Budget/Budget2005/budget05_zahlen_hintergruende_zusammenhaenge.pdf>.

- Camacho CJ, Higgins ET, Luger L. Moral value transfer from regulatory fit: what feels right is right and what feels wrong is wrong. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:498–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J, Grant H, Higgins ET. Regulatory fit and persuasion: transfer from “feeling right”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:388–404. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans LM, Petty RE. Self-guide framing and persuasion: responsibly increasing message processing to ideal levels. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:313–324. doi: 10.1177/0146167202250090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feld LPP, Frey BS. Tax evasion in Switzerland: the roles of deterrence and tax morale. [accessed 25.11.08]. 2006. < http://ssrn.com/abstract = 900351>.

- Florack A, Scarabis M. How advertising claims affect brand preferences and category-brand associations: the role of regulatory fit. Psychology & Marketing. 2006;23:741–755. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas AL, Liberman N, Higgins ET. Regulatory fit and resisting temptation during goal pursuit. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2002;38:291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gërxhani K, Schram A. Tax evasion and income source: a comparative experimental study. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2006;27:402–422. [Google Scholar]

- Hasseldine JD, Hite PA. Framing, gender and tax compliance. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2003;24:517–533. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist. 1997;52:1280–1300. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.12.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention: regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. vol. 30. Academic Press; New York: 1998. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Making a good decision: value from fit. American Psychologist. 2000;55:1217–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. How self-regulation creates distinct values: the case of promotion and prevention decision making. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2002;12:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET, Roney C, Crowe E, Hymes C. Ideal versus ought predilections for approach and avoidance: distinct self-regulatory systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:276–286. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET, Friedman RS, Harlow RE, Idson LC, Ayduk ON, Taylor A. Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: promotion pride versus prevention pride. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;31:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET, Spiegel S. Promotion and prevention strategies for self-regulation: a motivated cognition perspective. In: Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, editors. Handbook of Self-regulation: Research, Theory and Applications. Guilford Press; New York: 2004. pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann E, Hoelzl E, Kirchler E. Preconditions of voluntary tax compliance: knowledge and evaluation of taxation, norms, fairness, and motivation to cooperate. Journal of Psychology. 2008;216(4):209–217. doi: 10.1027/0044-3409.216.4.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler M, Hoelzl E, Kirchler E, Leder S, Manetti L. Framing of information on the use of public finances, regulatory fit of recipients and tax compliance. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2008;29(4):597–611. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idson LC, Liberman N, Higgins ET. Imagining how you’d feel: the role of motivational experiences from regulatory fit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:926–937. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E. The Economic Psychology of Tax Behaviour. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E. The burden of new taxes: acceptance of taxes as a function of affectedness and egoistic versus altruistic orientation. Journal of Socio-Economics. 1997;26:421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E, Maciejovsky B. Steuermoral und Steuerhinterziehung. In: Frey D, von Rosenstiel L, editors. Enzyklopädie der Psychologie. Wirtschaftspsychologie; Hogrefe, Göttingen: 2002. et al. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler E, Hölzl E, Wahl I. Enforced versus voluntary tax compliance: the “slippery slope” framework. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2008;29(2):210–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lee AY, Aaker JL, Gardner WL. The pleasures and pains of distinct self-construals: the role of interdependence in regulatory focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:1122–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A, Carrera S, Cullis J, Jones P. Individual, cognitive and cultural differences in tax compliance: UK and Italy compared. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2009;30(3):431–445. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Idson LC, Camacho CJ, Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention choices between stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1135–1145. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw K, Scholz J. Norms, social commitment and citizens’ adaptation to new laws. In: Koppen PV, Hessing DJ, Van de Heuvel C, editors. Lawyers on Psychology and Psychologists on Law. Swets and Zeitlinger; Berwyn, PA: 1988. pp. 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze Entrate Tributarie (Gennaio–Dicembre 2005) [accessed 25.11.08]. 2005. < http://www.finanze.gov.it/export/download/comunicare/dicembre2005.pdf>.

- Pham MT, Avnet T. Ideals and oughts and the reliance on affect versus substance in persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research. 2004;30:503–518. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ML. An experimental approach to changing taxpayers’ attitudes towards fairness and compliance via television. Journal of the American Taxation Association. 1994;16(1):67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F. Shadow economies around the world: what do we really know? European Journal of Political Economy. 2005;21(3):598–642. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel S, Grant-Pillow H, Higgins ET. How regulatory fit enhances motivational strength during goal pursuit. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2004;34:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N, Wenzel M. The effects of different letter styles on reported rental income and rental deductions: an experimental approach. 2001. Centre for Tax System Integrity Working Papers, No. 11.

- Torgler B. To evade taxes or not to evade: that is the question. Journal of Socio-Economics. 2003a;32:283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler B. Tax morale in transition countries. Post-Communist Economies. 2003b;15(3):357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M. The impact of outcome orientation and justice concerns on tax compliance: the role of taxpayers’ identity. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87(4):629–645. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RR, Curratola AP, Samson WD. A behavioral study investigating the effect of increasing tax knowledge and fiscal policy awareness on individual perceptions of federal income tax fairness. Advances in Taxation. 1990;3:165–185. [Google Scholar]