Abstract

Background

The mood disorders are prevalent and problematic. We review randomized controlled psychotherapy trials to find those that are empirically supported with respect to acute symptom reduction and the prevention of subsequent relapse and recurrence.

Methods

We searched the PsycINFO and PubMed databases and the reference sections of chapters and journal articles to identify appropriate articles.

Results

One hundred twenty-five studies were found evaluating treatment efficacy for the various mood disorders. With respect to the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), and behavior therapy (BT) are efficacious and specific and brief dynamic therapy (BDT) and emotion-focused therapy (EFT) are possibly efficacious. CBT is efficacious and specific, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) efficacious, and BDT and EFT possibly efficacious in the prevention of relapse/recurrence following treatment termination and IPT and CBT are each possibly efficacious in the prevention of relapse/recurrence if continued or maintained. IPT is possibly efficacious in the treatment of dysthymic disorder. With respect to bipolar disorder, CBT and family-focused therapy (FFT) are efficacious and interpersonal social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) possibly efficacious as adjuncts to medication in the treatment of depression. Psycho-education (PE) is efficacious in the prevention of mania/hypomania (and possibly depression) and FFT is efficacious and IPSRT and CBT possibly efficacious in preventing bipolar episodes.

Conclusions

The newer psychological interventions are as efficacious as and more enduring than medications in the treatment of MDD and may enhance the efficacy of medications in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Keywords: Randomized controlled trials, major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, qualitative review

INTRODUCTION

The mood disorders are characterized by episodes of depression or mania and are among the most prevalent of the psychiatric disorders.[1] Major depressive disorder (MDD) and the less severe but more chronic dysthymic disorder (DD) involve depression only, whereas bipolar disorder (BD) requires episodes of mania or hypomania.[2] The mood disorders account for the vast majority of suicides and are a leading cause of disability.[3]

Both psychotherapy and medications are widely used in the treatment of the mood disorders.[4] Historically, the primary focus of treatment development was on symptom reduction, but there has been a growing recognition of the need to develop strategies that prevent subsequent relapse and recurrence.[5] Medication treatment has long been considered the standard of treatment for more severe depression and bipolar disorder and has gained market share relative to psychotherapy in recent years with the advent of less problematic medications.[6] Nonetheless, not everyone responds to medications and there is no evidence that drugs do anything to reduce risk for subsequent symptom return once their use is discontinued. Some patients respond to psychotherapy who are refractory to medications and it has long been claimed that psychotherapy has enduring effects that can reduce subsequent risk in ways that medications cannot.

In this article, we review studies of psychological therapies for the mood disorders in adults to determine which ones are empirically supported using the criteria defined by Chambless and Hollon.[7] According to these criteria, a therapy is considered efficacious and specific if there is evidence from at least two settings that it is superior to a pill or psychological placebo or another bona fide treatment. If there is evidence from two or more settings that the therapy is superior to no treatment it is considered efficacious. If there is support from one or more studies from just a single setting, the therapy is considered possibly efficacious pending replication. We further differentiate between the effects of treatment on the reduction of acute symptoms versus the prevention of subsequent relapse or recurrence and pay particular attention to comparisons to medications. Earlier reviews have applied these criteria and we update those reviews.[8,9]

This approach is similar to the one taken by the FDA in determining when a medication can be marketed in the United States. It puts a premium on well-formed studies in fully clinical populations that speak to the efficacy and specificity of a given intervention and requires direct comparisons to draw inferences regarding the relative efficacy of different interventions. As a consequence, it sometimes leads to different conclusions than are drawn from meta-analyses that tend to include all studies in a literature (regardless of quality) and that estimate differential effect sizes in the absence of direct comparisons between conditions. Meta-analytic reviews often find comparable effect sizes between different psychotherapies even when only some of those interventions would meet FDA criteria for efficacy and specificity.[10] In such instances, we are reluctant to declare a treatment efficacious (much less specific) if we cannot find a single well-formed study that supports that conclusion. To do so would be tantamount to accepting the null hypothesis and interpreting the absence of differences between treatments as evidence of comparable efficacy (or specificity). We highlight this distinction when it occurs in the following review.

Despite our preference for the FDA approach, we do think that meta-analyses have considerable value in highlighting the relative impact of different control conditions and other related factors. For example, Cuijpers and colleagues reported that comparisons between all psychotherapies aggregated versus no treatment controls generated an effect size of d = .88 across the depression literature.[11] This can be translated into a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 2.15 and means that one additional patient gets better for just over every two patients treated relative to what would have happened in the absence of treatment. Such comparisons are sufficient to establish efficacy. Non-specific controls (including especially pill-placebos) more than halved the effect size (d = .35), which translates into a considerably larger NNT of 5.15. This means that over twice as many patients would need to be treated to produce one additional positive outcome relative to comparison conditions that mobilize nonspecific factors associated with going into treatment. This is still quite respectable; by way of contrast, antihypertensive medications produce an NNT of 15. Such comparisons are necessary to establish specificity. In brief, it is easier to show that something works than it is to establish that it works for specific reasons that go beyond the mere provision of treatment. Curiously, comparisons to “treatment-as-usual” were associated with an intermediate effect size of d = .52 with a corresponding NNT of 3.50. This likely reflects the fact that what passes as “treatment-as-usual” can be quite heterogeneous across studies (and even across patients within studies), ranging from minimal contact to rather extensive care. It is important to note that all such indices are relative in nature and can only be interpreted in terms of the comparison or control conditions against which they were generated.

METHOD

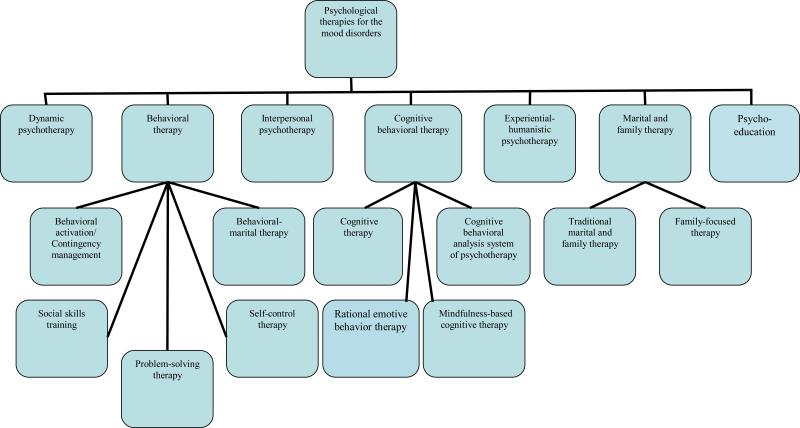

The method of this review is very similar to those of two other reviews we carried out to determine which psychological therapies are empirically supported for adults with social phobia[12] or acute stress and posttraumatic stress disorders.[13] We carried out a literature search of the PsycINFO and PubMed databases and the reference sections of chapters and journal articles to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychological therapies for the mood disorders through the end of 2009. Trials were included only if adult patients with a diagnosed mood disorder were randomly allocated to different treatments including one or more psychosocial interventions. The method of the intervention had to be clearly described and the articles written in English. Therapeutic approaches evaluated in the trials were classified as dynamic, interpersonal, cognitive-behavioral, behavioral, experiential-humanistic, marital/family, or psycho-educational (see Figure 1). Chambless & Hollon's (1998) criteria were used to draw conclusions about the efficacy of each.[7]

Figure 1.

Classification of psychological therapies for the mood disorders

RESULTS

Major Depressive Disorder

As shown in Table 1, 101 RCTs were identified with respect to MDD. These trials evaluated the efficacy of dynamic psychotherapy (N=17), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (N=19), cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) (N=64), behavior therapy (BT) (N=22), experiential-humanistic psychotherapy (N=6), and marital/family therapy (N=2).

Table 1.

Major Depressive Disorder (Adult and Geriatric)

| Study | Treatment/s | Number of Sessions | Control Condition/s | Age of subjects | Sample size | Diagnosis | Setting | Therapists' qualification | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic: | |||||||||

| Covi et al 1974[15] | Dynamic psychotherapy vs brief supportive contacts crossed with medication vs placebo | 16 90-minute group sessions over 17 weeks | Pill-placebo plus brief supportive contacts | Adults aged 20-50 | 207 assigned of whom 146 completed | Depressed outpatients with elevated symptoms | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Experienced psychiatrists | Dynamic psychotherapy less efficacious than medications and no better than pill-placebo and did nothing to enhance the efficacy of medications |

| McLean & Hakstian 1979[14] | Dynamic psychotherapy vs contingency management (BT) vs medication | 10 weekly 60-minute sessions | Relaxation therapy (RT) | Adult aged 20-60 | 196 assigned of whom 154 completed | Feighner criteria definite depressive syndrome | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Psychiatrists and psychologists with greater or lesser experience | Dynamic psychotherapy less efficacious than other conditions with BT most efficacious of all |

| Gallagher & Thompson 1982[29] | Dynamic psychotherapy vs cognitive therapy (CT) vs behavior therapy (BT) | 16 sessions 12 weeks (1 year naturalistic follow-up) | None | Elderly aged 55 plus | 30 assigned (attrition not reported) | RDC MDD | Geriatric clinic at university medical center | Pre- and post-doctoral psychologists | No differences in terms of acute response although better maintenance of gains for CT or BT than for dynamic psychotherapy |

| Kornblith et al 1983[18] | Dynamic psychotherapy vs three different versions of self-control therapy (SCT) | 12 weekly group sessions | None | Adult women aged 18-60 | 49 assigned of whom 39 completed | RDC MDD | Outpatient research clinic in academic psychology department | Graduate students in psychology (SCT) and MSW candidate (dynamic) | No differences between the groups |

| Hersen et al 1984[17] | Dynamic psychotherapy vs social skills training crossed with medication vs placebo | 12 weekly sessions (plus 6-8 subsequent visits over 6 months) | None | Adult women aged 21-60 | 120 assigned of whom 82 completed | Feighner criteria primary depression (DSM-III MDD) | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Experienced psychologists (psychotherapy conditions) and medical clinic personal (medications) | No differences with respect to acute response |

| Steuer et al 1984[33] | Dynamic psychotherapy vs cognitive behavior therapy (CT) | 46 two-hour group sessions over 9 months | None | Elderly aged 55 plus | 35 assigned of whom 20 completed | DSM-III MDD | Geriatric clinic at VA medical center | Pre/post-doctoral psychologists and masters level social workers | CT better than dynamic psychotherapy with respect to acute response |

| Covi et al 1987[16] | Dynamic psychotherapy vs cognitive therapy (CT) with and without medications | 16 group sessions over 14 weeks then 4 weeks of individual sessions | None | Adults aged 18-70 | 90 assigned of whom 70 completed | RDC MDD | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Psychiatrist and psychologist | Dynamic psychotherapy less efficacious than CT with or without medications |

| Thompson et al 1987[30] | Dynamic psychotherapy vs cognitive therapy (CT) vs behavior therapy (BT) | 16-20 sessions in 12 weeks | 6-week delayed treatment control | Elderly aged 60 plus | 109 assigned of whom 91 completed | RDC MDD | Geriatric clinic at VA medical center | Doctoral level clinical psychologists | Active treatments did not differ and better than delayed treatment when pooled |

| Gallagher-Thompson et al 1990[31] | No differences in follow-up | ||||||||

| Gallagher-Thompson & Steffen, 1994[32] | Brief psychodynamic psychotherapy vs cognitive therapy (CT) | 16-20 sessions over 12 weeks | None | Adult caregivers of frail elderly | 66 assigned of whom 52 completed | RDC Major, Minor, or Intermittent Depression | Geriatric clinic at VA medical center | Doctoral level clinical psychologists and masters level social workers | Short-term caregivers did better in dynamic and long-term caregivers better in CT |

| Shapiro et al 1994[19] | Dynamic interpersonal psychotherapy vs cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) | 8 or 16 sessions | None | Adults mean age 40 (± 10) | 150 assigned of whom 117 completed | DSM-III MDD | Research clinic | Clinical psychologists | No differences on most measures (CBT better on one) but longer treatment better for more severe |

| Barkham et al 1996[20] | 36 additional patients added | ||||||||

| De Jonghe et al 2001[24] | Dynamic psychotherapy plus medication vs medication alone | 16 sessions (weekly for 8 weeks then biweekly thereafter) | None | Adults aged 18-60 | 167 assigned of whom 129 completed | DSM-III-R MDD | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Experienced psychotherapists (discipline unspecified) and psychiatric residents | Combined treatment reduced attrition and thereby increased overall rates of recovery over ADM alone |

| Kool et al 2003[25] | |||||||||

| Combined treatment better than medications alone for patients with personality disorders | |||||||||

| Burnand et al 2002[22] | Dynamic psychotherapy plus medication vs supportive care plus medication | 10 week treatment program (session frequency not stated) | None | Adults aged 20-65 | 95 assigned of whom 74 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Community mental health center | Experienced research nurses under psychoanalytic supervision | No differences on symptom measures but dynamic psychotherapy reduced rates of MDD and promoted work adjustment better than supportive care |

| Cooper et al 2003[21] | Dynamic therapy vs cognitive behavior therapy vs non-directive counseling | Weekly sessions from week 8 to18 postpartum | Routine primary care | Adult women aged 17-42 | 193 assigned of whom 171 completed | DSM-III-R MDD post-partum women | Patient homes | Specialists in the research treatment and non-specialists | Active treatments all superior to control at 4.5 months but not at 9 months post-partum and only dynamic reduced rates of diagnosed depression relative to routine care |

| Maina et al 2007[27] | Brief dynamic therapy plus antidepressant medications (BDT/ADM) | 15 to 30 sessions over 6 months of active treatment followed by 6 months of medication continuation | Brief supportive psychotherapy plus antidepressant medications (BSP/ADM_ | Adults aged 18-65 | 148 assigned of whom*** completed | DSM-IV MDD single episode and presence of focal problem or precipitant life event | Research clinic at university medical center | Psychiatrists who had completed personal training in psychodynamic psychotherapy | Adding BDT to ADM no better than adding BSP at end of treatment but BDT showed continued improvement across 6-month continuation phase |

| Maina et al 2009[28] | Prior BDT reduced rates of recurrence across 48 month treatment-free follow-up | ||||||||

| Dekker et al., 2008[26] | Short-term psychodynamic supportive psychotherapy (SPSP) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 8 weekly sessions | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 141 assigned of whom 103 completed treatment | DSM-IV MDD | Community mental health center | Trained psychiatrists and psychotherapists not otherwise specified | Medication superior to SPSP but differences diminishing from weeks 4 through 8 |

| Salminen et al., 2008[23] | Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP) vs medication | 16 weekly session | None | Adults aged 20-60 | 51 assigned of whom 40 completed | DSM-IV MDD (mild and moderate) | General practice setting | Experienced psychiatrists and psychologists with two years training in STDP | No differences between groups on any outcomes |

| Interpersonal: | |||||||||

| Klerman et al 1974 (relapse)[36] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs medication vs combined treatment | 32-36 weekly sessions in 8 months | Pill-placebo vs no pill (alone and combined with IPT) | Adult women with a median age in the late 30's and range unspecified | 150 assigned of whom 139 completed | DSM-II neurotic depression (with bipolar) | Outpatient research clinics at university medical centers | Masters' level social workers | IPT as efficacious as medications in preventing relapse if provided without pill-placebo |

| Weissman et al 1974 (social adjustment)[37] | IPT had delayed effect on enhance social adjustment | ||||||||

| Weissman et al 1979 (acute)[38] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs medications vs combined treatment | 16 sessions 16 weeks | Treatment-on-demand nonspecific control | Adults aged 18-65 | 96 assigned of whom 81 completed | RDC MDD (primary) | Outpatient research clinics at university medical centers | Psychiatrists | IPT as efficacious as medications and combined better still with all superior to nonspecific control (acute) |

| DiMascio et al 1979 (acute)[39] | |||||||||

| Weissman et al 1981 (social adjustment / relapse prevention)[40] | 1 year naturalistic follow-up | IPT again had delayed effect on social adjustment but not relapse | |||||||

| Elkin et al 1989, 1995(acute)[41,42] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs cognitive therapy (CT) vs medication | 16-20 sessions over 16 weeks | Pill-placebo | Adults with a mean age of 35 ± 8.5 years | 250 assigned of whom 155 completed | RDC MDD (primary) | Outpatient research clinics at university medical centers | Psychiatrists and doctoral level clinical psychologists | IPT or medications better than CT or pill-placebo among more severe patients with no differences among less severe patients (acute) |

| Watkins et al., 1993[43] | |||||||||

| Drugs faster than IPT or CT | |||||||||

| Shea et al., 1992 (relapse prevention)[99] | Prior CBT vs prior IPT vs prior medications | 18 month naturalistic follow-up | Medication withdrawal | No differences with respect to relapse prevention | |||||

| Frank et al 1990[59] | Maintenance phase interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs maintenance medication vs combined treatment | 36 monthly sessions (after up to 36 weeks treatment with IPT plus drugs) | Pill-placebo control (alone and combined with IPT) | Adults aged 21-65 | 128 assigned of whom 106 completed | RDC MDD with history of recurrence and currently in recovery | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Social workers, psychologists, or nurse clinicians with masters or doctorates | IPT more efficacious than pill-placebo control but less efficacious than and did little to enhance the efficacy of maintenance medication in prevention of recurrence |

| Schulberg et al 1996[52] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs medication | 16 weekly sessions (and 4 monthly sessions) | Treatment as usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-64 | 276 assigned of whom 150 completed | DSM-III-R MDD | Primary care setting | Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists | IPT as efficacious as medications and both superior to TAU |

| Markowitz et al 1998[49] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs medications | 16 sessions 17 weeks | Supportive therapy | Adults (HIV) aged 24-59 | 101 assigned of whom 69 completed | HIV+ with depression (about half met for DSM III-R MDD) | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Psychiatrists and social workers (IPT) and clinical psychologists (CBT) | IPT or medications both produced better acute response than either CBT or supportive psychotherapy |

| Reynolds, Frank et al 1999[61] | Maintenance phase interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs maintenance medication vs combined treatment | 36 monthly sessions (after up to 36 weeks of combined treatment) | Pill-placebo control (alone and combined with IPT) | Elderly aged 60 or older | 107 assigned of whom 96 completed | RDC MDD with history of recurrence and currently in recovery | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Masters level social workers and masters and doctoral level psychologists | IPT more efficacious than pill-placebo control and comparable to and enhanced the efficacy of maintenance medications in prevention of recurrence |

| Reynolds, Miller et al 1999[57] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs medication vs combined treatment | 16 sessions over 16 weeks | Pill-placebo control (alone and combined with IPT) | Elderly aged 50 or older | 80 assigned of whom 73 completed | RDC MDD in recently bereaved | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Psychiatrists | IPT no better than placebo and did nothing to enhance the efficacy of medications |

| O'Hara et al., 2000[44] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) | 12 weekly 60-minute sessions | Wait list control | Adult women aged 18 and above | 120 assigned of whom 99 completed | DSM-IV MDD in postpartum females | Private practice settings | Doctoral level clinical or counseling psychologists | IPT reduced depressive symptoms and improved social adjustment |

| Judd et al 2001[53] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) plus medication | 12 sessions | Treatment as usual (TAU) plus ADM | Adults aged 18-65 | 32 assigned of whom 28 completed | DSM-IV MDD | General practice | General practitioners | Depression improved in both treatments but no differences between conditions |

| Bolton et al., 2003[50] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) | 16 weekly 90-minute group sessions | No treatment | Adults | 341 assigned of whom 224 completed | DSM-IV MDD (and sub-thresh) | Rural Ugandan villages | Indigenous nonprofessionals trained in IPT | Group IPT superior to no treatment control |

| Bass et al., 2006[51] | Differences favoring IPT sustained over 6 month follow-up | ||||||||

| Spinelli & Endicott 2003[45] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) modified for antepartum depression | 16 weekly sessions | Didactic parent education | Adult women aged 18-45 | 50 assigned of whom 38 completed | DSM-IV MDD in pregnant women | Outpatient research clinic | Experienced therapists | IPT produced greater rate of improvement than did didactic parenting control (60% vs 15%) |

| Reynolds et al 2006[62] | Maintenance phase interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs clinical management crossed with maintenance medications (ADM) vs pill-placebo | Monthly maintenance sessions for two years | Pill-placebo control (alone and combined with IPT) | Geriatric aged 70 and above | 116 assigned of whom 90 completed maintenance phase | DSM-IV MDD and response to combined treatment | Outpatient research clinic | Experienced IPT therapists (nurses, social workers, and psychologists) | ADM better than placebo with or without IPT but no effect for IPT with or without medications |

| Carreira et al 2009[63] | IPT protects against recurrence in cognitively impaired unmedicated patients | ||||||||

| Van Schaik et al 2006[58] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) | 10 sessions over 5 months | Treatment as usual (TAU) | Geriatric aged 55 and older | 143 assigned of whom 120 completed | PRIME-MD depression | General practice settings (x12) | Psychologists and psychiatric nurses | IPT associated with fewer patients who still met criteria for depression than TAU but no differences in more stringent rates of remission |

| Luty et al 2007 (acute)[46] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) | 8-19 sessions over 16-20 weeks | None | Adults aged 18 and above | 177 assigned of whom 159 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Outpatient research clinic | Experienced therapists with MD or PhD | CBT better than IPT at level of nonsignificant trend in full sample and superior for more severe or Axis II patients |

| Joyce et al 2007 (personality)[47] | |||||||||

| Schramm et al 2007[54] | Interpersonal psychotherapy plus antidepressant medication (Comb) vs antidepressant medication alone | 15 individual and 8 group sessions over 5 weeks | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 130 assigned of whom 105 completed | DSM-IV MDD (included bipolar II) | Inpatient psychiatric hospital | Psychiatrists and psychologists who completed 3-year training program in IPT | Combined treatment superior to medications alone |

| Schramm et al 2008[55] | Indications of enduring effect for prior IPT | ||||||||

| Marshall et al 2008[48] | Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) vs cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs antidepressant medications | 16 weekly sessions | None | Adults (age unspecified) | 159 assigned of whom 102 completed | DSM-IV MDD | University affiliated research clinic | Doctoral level psychologists and pre-doctoral psychology graduate students | IPT less efficacious than medication with CT not differing from either |

| Swartz et al 2008[56] | Interpersonal psychotherapy for mothers of children with psychiatric illnesses (IPT-MOMS) | Engagement interview followed by 8 sessions of IPT | Treatment as usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-65 | 65 assigned of whom 47 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Pediatric mental health clinic | Masters or doctoral level therapists with degrees in social work, nursing, psychology, or psychiatry | IPT-MOMS more efficacious than TAU in terms of depressive symptoms and global functioning in moms and depression in offspring |

| Cognitive: | |||||||||

| Rush et al 1977 (acute)[66] | Cognitive therapy (CT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 20 sessions 12 weeks | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 41 assigned of whom 32 completed | Feighner definite depression (DSM-II neurotic) | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Psychiatrists, psychiatric residents and pre- and post-doctoral psychologists | CBT better than ADM (acute) |

| Kovacs et al 1981 (relapse)[93] | Prior CBT | 12 month naturalistic follow-up | Medication withdrawal | Prior CBT better than prior ADM at preventing relapse | |||||

| Blackburn et al 1981 (acute)[67] | Cognitive therapy (CT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) vs combined | 15-20 sessions in 12-20 weeks | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 88 assigned of whom 64 completed | RDC primary major depression | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center and general practice clinic | Doctoral level clinical psychologists | CBT (with or without ADM) better than ADM alone in community sample with combined better than either monotherapy in psychiatric setting (acute) |

| Blackburn et al 1986 (relapse / recurrence)[94] | Prior CBT with boosters through month six | 24 month naturalistic follow-up | Medication withdrawal after month six | Prior CBT (with or without ADM) better than prior ADM preventing recurrence | |||||

| Murphy et al 1984 (acute)[68] | Cognitive therapy (CT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) vs combined | 20 sessions in 12 weeks | Placebo (only in combination with CBT) | Adults aged 18-60 | 95 assigned of whom 70 completed | Feighner definite depression RDC MDD primary | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Psychiatrists, psychiatric residents and pre- and post-doctoral psychologists | No differences between conditions (acute) |

| Simons et al 1986 (relapse)[95] | Prior CBT | 12 month naturalistic follow-up | Medication withdrawal | Prior CBT better than prior ADM at preventing relapse | |||||

| Teasdale et al 1984[87] | Cognitive therapy (CT) added to treatment as usual | 20 sessions over 12 weeks | Treatment-as-usual including medications (TAU) | Adults aged 18-60 | 44 assigned of whom 34 completed | RDC MDD | General practice | Doctoral level clinical psychologists trained in CT at Center for Cognitive Therapy | Adding CT enhanced the effects of TAU |

| Miller et al., 1989[84] | Cognitive therapy plus antidepressant medications (CT/ADM) vs behavior therapy plus antidepressant medications (BT/ADM) vs antidepressant medications (ADM) | Daily sessions during inpatient stay and then 20 weekly outpatient sessions | None | Adults with a mean age in the mid-to-late 30's | 46 assigned of whom 32 completed | DIS MDD | Inpatient medical setting | Experienced clinical psychologists (CT and BT) and research psychiatrists (ADM) | CT and BT both enhanced the efficacy of ADM alone although differences did not emerge until after discharge from inpatient setting |

| Bower et al 1990[85] | Cognitive therapy plus antidepressant medications (CT/ADM) vs behavior therapy plus antidepressant medications (BT/ADM) vs antidepressant medications (ADM) | 12 session in 30 days | None | Adults aged 18-60 | 30 assigned of whom 30 completed | DSM-III MDD | Inpatient medical setting | Single experienced clinical psychologist (study author) | CT and BT each enhanced efficacy of ADM |

| Selmi et al 1990[129] | Computer-administered cognitive behavioral therapy (CaCBT) vs therapist-administered CBT | 6 weekly sessions | Wait list | Adults with mean age in late 20's | 36 assigned of whom 36 completed | RDC major, minor, or intermittent depression | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Graduate students in clinical psychology | Computer-assisted CBT as efficacious as therapist-administered CBT and both superior to wait list |

| Hollon et al 1992 (acute)[70] | Cognitive therapy (CT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) vs combined | 20 sessions in 12 weeks | None (acute) | Adults aged 18-65 | 107 assigned of whom 64 completed | RDC primary major depressive disorder | Outpatient research clinic at medical center and community | Doctoral level psychologist and ICSW level social workers | No differences between conditions (acute) |

| Evans et al 1992 (relapse)[96] | Prior CBT vs continue ADM | 24 month naturalistic follow-up | Medication withdrawal | mental health clinic | Prior CBT as efficacious as continued ADM and better than ADM withdrawal at preventing relapse | ||||

| Scott & Freeman 1992[89] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) vs social work counseling (SWC) | 16 weekly sessions | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-65 | 121 assigned of whom 105 completed | DSM-III MDD | General practice clinics | Clinical psychologists (CBT) and social workers (SWC) | Few differences among the conditions but those that were evident tended to favor social work counseling |

| Fava et al., 1994[100] | WBT added to ADM vs ADM alone in recovered patients with history of recurrence | 10 sessions in 20 weeks to 24 month naturalistic follow-up | Medication withdrawal during 24 month naturalistic follow-up | Adults with mean age in mid-40's | 43 assigned of whom 40 completed | DSM-III-R MDD in full remission | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Single research psychiatrist | Prior exposure to CBT reduced residual symptoms relative to clinical management following medication withdrawal |

| Murphy et al 1995[68] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs relaxation training (RT) vs antidepressant medications (ADM) | 20 sessions over 16 weeks | None | Adults aged 18-60 | 37 assigned of whom 24 completed | Feighner criteria for MDD | Outpatient research clinic with patients recruited via advertisement | Graduate students in psychology, doctoral level psychologist and clinical social worker | CBT and RT both superior to ADM and did not differ from one another (it is not clear why ADM did so poorly in this study) |

| Blackburn & Moore 1997[83] | Cognitive therapy followed by cognitive therapy (CT/CT) vs antidepressant medication followed by antidepressant medications (ADM/ADM) vs antidepressant medications followed by cognitive therapy (ADM/CT) | 16 weekly sessions (acute)/27 monthly sessions over next 2 years (maintenance) | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 75 assigned of whom 67 completed | RDC MDD primary | Outpatient research clinic (UMC) with referrals from general practice | Experienced clinical psychologists | No differences between treatments during acute or maintenance treatment |

| Scott et al., 1997[86] | Cognitive behavior therapy plus treatment-as-usual (CBT/TAU) | 6 weekly 30-minute sessions | Treatment- as-usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-65 | 48 assigned of whom 34 completed | DSM-III-R MDD | Primary care | Professional discipline not specified | Combined treatment with CBT better than TAU alone |

| Fava et al., 1998[101] | WBT added to ADM vs ADM alone in recovered patients with history of recurrence | 10 sessions in 20 weeks to 24 month naturalistic follow-up | Medication withdrawal during 24 month naturalistic follow-up | Adults with mean age in late 40's | 40 assigned of whom 40 completed | RDC major depressive disorder in full remission | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Single research psychiatrist | Prior exposure to WBT prevented recurrence following medication withdrawal |

| Bright et al 1999[80] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs mutual support group therapy (MSG) | Weekly 90-minute sessions over 10 weeks | None | Adults aged 18-60 | 98 assigned of whom 68 completed | DSM-III-R MDD or dysthymia or depression NOS | Outpatient psychology department clinic | Professional therapists and para-professional therapists | No differences between the treatment conditions with some indications of advantage for professional therapists within CBT conditions |

| Jarrett et al 1999[75] | Cognitive therapy (CT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 20 sessions over 10 weeks | Pill-placebo | Adults with mean age in late 30's | 108 assigned of whom 71 completed | DSM-III-R MDD (atypical subtype) | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Psychiatrist and doctoral level psychologists | CBT or ADM both superior to pill-placebo (acute) |

| Paykel et al 1999[102] | Cognitive therapy added to ongoing antidepressant medication (CT plus ADM) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) for residual depression | 16 sessions in 20 weeks (with 2 extra booster sessions) followed by 48 week follow-up phase during which ADM continued | None | Adults aged 21-65 | 158 patients of whom 127 completed | DSM-III-R MDD in partial remission with residual symptoms | Outpatient research clinic at two university medical centers | Professional discipline not specified but all experienced | Adding CBT enhanced the efficacy of ADM in terms of enhancing full remission and preventing subsequent relapse and recurrence |

| Paykel et al 2005[103] | Six year follow-up found that enduring effects persisted through the first three years of follow-up | ||||||||

| Keller et al 2000 (acute)[116] | Cognitive behavioral analytic system for psychotherapy (CBASP) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) vs combination (CBASP/ADM) | 16 sessions in 12 weeks (acute phase) | None | Adults aged 18-75 | 681 assigned of whom 519 completed | DSM-IV chronic major depressive disorder or current MDD superimposed on dysthymia | Outpatient research clinics at university medical centers | Psychiatrists, doctoral level psychologists, and MSW level social workers | Combined treatment better than either single modality which did not differ (acute) |

| Klein et al 2004 (recurrence)[118] | CBASP | 13 monthly sessions over 52 weeks of maintenance | Assessment only control | Adults mean age 45.1 ± 11.4 years | 82 assigned of whom 61 completed | Acute and crossover CBASP responders | Maintenance CBASP reduced rate of recurrence relative to assessment only | ||

| Teasdale et al 2000[109] | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) superimposed on treatment-as-usual (TAU) | 8 weekly two hour sessions followed by 52 week naturalistic follow-up | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-65 | 145 assigned of whom 132 completed | DSM-III-R MDD with history of recurrence in full remission or recovery | Outpatient research clinics | Doctoral level clinical psychologists | MBCT plus TAU better than TAU at preventing relapse and recurrence in recovered patients with 3 or more prior episodes |

| Jarrett et al 2001[119] | Continuation cognitive therapy (C-CT) (following 20 sessions of acute phase CT) | 10 sessions in 8 months (followed by 16 months of naturalistic follow-up) | Assessment only control (following 20 sessions of acute phase CT) | Adults aged 18-65 | 84 assigned of whom 76 completed | DSM-IV MDD recurrent in remission | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Professional discipline not specified but all experienced | C-CT better than assessment only control in reducing risk for relapse and recurrence in remitted patients |

| Thompson et al (2001)[124] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) vs combined treatment (CBT/ADM) | 16-20 sessions over 12-16 weeks | None | Geriatric aged 60 and over | 102 assigned of whom 71 completed | RDC MDD as ascertained by SADS | Outpatient research clinic at VA hospital and university medical center | Clinical psychologists with at least 1-year experience treating geriatric patients | Combined treatment generally better than ADM alone (especially with more severely depressed patients) with CBT alone intermediate and closer to combined |

| Perlis et al 2002 (sequential)[107] | Cognitive therapy added to ongoing antidepressant medication (CT/ADM) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 12 weekly sessions followed by 7 biweekly sessions | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 132 assigned of whom 85 | DSM-III-R MDD in remission | Outpatient research clinic | Doctoral level clinical psychologists | Adding CBT to ADM no better than increasing ADM dose in reducing relapse or residual symptoms |

| Miranda et al 2003[90] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 8 weekly sessions followed by 8 more if needed | Community referral (CR) | Adults mean age 29.3 ± 7.9 years | 267 | DSM-IV MDD in mostly low-income minority women | County clinics, research offices and patient homes | Experienced psychotherapists | Both CBT and ADM reduced depression more than CR |

| Miranda et al 2005[91] | 12- month follow-up | Both continued CBT and ADM superior to CR | |||||||

| Ma & Teasdale 2004[110] | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) superimposed on treatment-as-usual (TAU) | 8 weekly two hour sessions followed by 52 week naturalistic follow-up | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-65 | 75 assigned of whom 69 completed | DSM-III-R MDD with history of recurrence in full remission or recovery | Outpatient research clinic | Experienced cognitive therapists | MBCT plus TAU better than TAU alone at preventing relapse and recurrence in recovered patients with 3 or more prior episodes |

| Bockting et al 2005[104] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) superimposed on treatment-as-usual (TAU) | 8 two-hour weekly sessions | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Adults with mean age in mid 40's | 187 assigned of whom 165 completed | DSM-IV MDD with at least 2 prior episodes | Recruited from psychiatric centers via advertisements | Psychologists (including first author) | CBT plus TAU better than TAU alone at preventing relapse and recurrence with larger effects for patients with more prior episodes |

| Cuijpers et al 2005[92] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) | Mean of 10 sessions (SD 11) | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-65 | 425 assigned of whom 288 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Outpatient mental health centers | Experienced therapists | No differences among less severe but CBT superior to TAU among more severe |

| DeRubeis et al 2005 (acute)[76] | Cognitive therapy (CT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 24 sessions 16 weeks | Pill-placebo | Adults aged 18-65 | 240 assigned of whom 204 completed | DSM-IV MDD (severe) | Outpatient research clinics at university medical centers | Doctoral level psychologists and psychiatric nurse | CT or ADM superior to pill-placebo control |

| Hollon et al 2005 (relapse)[97] | Prior CT vs continuation ADM | Medication withdrawal onto pill-placebo | Prior CT as efficacious as continued ADM and better than placebo withdrawal at preventing relapse | ||||||

| Wright et al 2005[130] | Computer-assisted cognitive therapy (CaCT) vs cognitive therapy alone (CT) | 9 sessions in 8 weeks | Wait list (WL) | Adults aged 18-65 | 45 assigned of whom 40 completed | DSM-IV MDD | University-affiliated psychiatric center | Master's and doctoral-level clinicians | CaCT comparable to live CT and both better than WL in reducing depression with gains maintained across 6-month follow-up |

| Smit et al 2006[102] | Cognitive behavior therapy plus depression recurrence prevention (CBT/DRP) vs DRP alone | 10-12 weekly sessions CBT then 3 sessions DRP | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-70 | 267 assigned of whom 240 completed | DSM-IV MDD (using CIDI) | Primary care (55 different practices) | Cognitive therapists (educational level and experience unspecified) | No differences between the conditions |

| Strauman et al (2006)[128] | Cognitive therapy (CT) vs self-system therapy (SST) | 20 sessions weekly for first 6 weeks and at least biweekly thereafter | None | Adults age unspecified | 45 assigned of whom 39 completed | DSM-IV MDD or dysthymia (except for six patients) | University-based research clinic | Doctoral-level clinical psychologists and predoctoral interns | No overall differences between the conditions but SST better than CT for patients who lacked promotion goals |

| Rohan et al (2007)[127] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs light therapy (LT) vs combined CBT plus LT (CBT/LT) | 12 90-minute sessions twice weekly over six weeks | Wait list | Adults aged 18 and older | 61 assigned of whom 54 completed | DSM-IV MDD recurrent with seasonal pattern | University-based research clinic | Doctoral level psychologist with graduate student co-therapists | All three active treatments comparable and each superior to wait list control |

| Thase et al 2007[126] | Cognitive therapy alone (CT) or in combination with medication (COMB) vs medication switch or augmentation | 16 sessions over 12 weeks | None | Adults aged 18-75 | 304 assigned | DSM-IV MDD with nonresponse to medication treatment | Community mental health and university-based clinics and primary care settings | Doctoral level psychologists, psychiatrists, masters-level social workers and psychiatric nurses | CT did not differ from medication switch but medication augmentation faster than CT augmentation |

| Bagby et al 2008[82] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 16-20 weekly sessions | None | Adults aged 18-70 | 275 assigned of whom 174 completed | DSM-IV MDD | University-affiliated outpatient clinic | Master's and doctoral-level clinicians | No differences on continuous measures but ADM beat CT on response rates and with neurotic patients |

| Conradi et al 2008[105] | Cognitive behavior therapy plus psychoeducation (CBT/PE) vs psychoeducation (PE) | 10-12 CBT sessions followed by 3 PE sessions | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Adults aged 18-70 | 208 assigned with attrition not reported | DSM-IV MDD (using CIDI) | Primary care clinics | No information provided | CBT plus PE but not PE alone superior to TAU among patients with four or more prior episodes |

| David et al 2008[71] | REBT vs CT vs ADM (continued at reduced dose during follow-up) | 20 sessions over 14 weeks with 6 month follow-up | None | Adults with mean age in mid-30's | 170 assigned of whom 151 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Outpatient research clinic in university medical center | Doctoral-level psychologists and psychiatrists | No differences were evident between the conditions at end of treatment; REBT held up better than ADM at 6 months |

| Sava et al 2009[72] | REBT and CT both more cost-effective than ADM | ||||||||

| Faramarzi et al 2008[78] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) vs antidepressant medications (ADM) | 10 weekly two-hour group sessions | Assessment only control | Adult women with fertility problems | 124 assigned of whom 89 completed | DSM-III-R MDD | Outpatient research clinic in university medical center | Experienced clinical therapists | CBT superior to ADM which was in turn superior to assessment only control |

| Kuyken et al 2008[111] | MBCT plus medication taper vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 8 weekly sessions with four boosters over 52 week naturalistic follow-up | None | Adults aged 18 and above | 123 assigned of whom 104 completed treatment and 96 completed follow-up | DSM-IV MDD in remission with history of 3 or more prior episodes | Primary care | Doctoral level psychologists and occupational therapists | MBCT more effective than ADM in reducing residual symptoms and improving quality of life; 75% of MBCT patients able to discontinue ADM |

| Laidlaw et al 2008[125] | Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) | 8 sessions (on average) | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Geriatric aged 60 and over | 44 assigned of whom 40 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Primary care | Masters level clinical psychologists and one graduate psychologist | CBT superior to TAU with respect to categorical diagnoses (and some continuous measures after controlling for patient characteristics) |

| Manber et al 2008[121] | Cognitive behavior therapy plus antidepressant medication (CBT/ADM) vs sleep hygiene plus ADM | 5 weekly sessions followed by 2 biweekly sessions | None | Adults aged 18-75 | 30 assigned of whom 28 completed | DSM-IV MDD plus insomnia | Outpatient research clinic in university medical center | Two licensed clinical psychologists | CBT plus ADM superior to ADM plus sleep hygiene control in terms of rates of remission from both depression and insomnia |

| Dozois et al 2009[123] | Cognitive therapy plus antidepressant medication (CT/ADM) vs antidepressant medication alone (ADM) | 15 weekly sessions | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 48 assigned of whom 42 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Outpatient tertiary care clinic | Two licensed master's level therapists | Adding CT did little to enhance the effects of ADM but did improve cognitive structure |

| Freedland et al 2009[122] | Cognitive behavior therapy plus usual care (CBT/UC) vs supportive stress management plus usual care (SSM/UC) | 12-16 weekly sessions | Usual care (with approximately half of all participants receiving antidepressant medications) | Adults aged 21 and older | 123 assigned of whom 113 completed | DSM-IV MDD (66%) or minor depressive episode (34%) undergoing coronary bypass surgery in the last year | Outpatient research clinic in university medical center | Experienced doctoral level clinical or counseling psychologists or clinical social workers | CBT and SSM both superior to usual care with CBT having greater and more durable effects than SSM |

| Kocsis et al 2009 (acute)[120] | Cognitive behavioral analytic system for psychotherapy plus antidepressant medication ((CBASP/ADM) vs brief supportive psychotherapy plus antidepressant medication (BSP/ADM) | 16 sessions in 12 weeks | Flexible algorithm-driven individualized antidepressant medication (ADM) | Adults aged 18-75 | 491 assigned of whom 423 completed | DSM-IV chronic major depressive disorder or current MDD superimposed on dysthymia who did not respond to12 weeks of medication treatment | Outpatient research clinics at university medical centers | Psychiatrists, doctoral level psychologists, and MSW level social workers | Augmenting flexible algorithm medication treatment with CBASP (or BSP) no more efficacious than ADM alone |

| Serfaty et al 2009[88] | Cognitive behavioral therapy plus treatment as usual (CBT/TAU) vs talking control plus treatment as usual (TC/TAU) | Up to 12 individual sessions over 4 months | Treatment-as-usual (including medications for about half) (TAU) | Geriatric aged 65 and above | 204 assigned of whom 177 completed | DSM-IV MDD (88%) or minor depression (12%) | Primary care | Experienced cognitive behavioral therapists (degree not specified) | CBT superior to TC when each added to TAU |

| Wilkinson et al 2009[108] | Cognitive behavioral therapy plus antidepressant medication (CBT/ADM) | Up to 8 90-minute group sessions | Antidepressant medication (ADM) | Geriatric aged 60 and above | 45 assigned of whom 36 completed | ICD MDD within last year and remitted for at least 2 months on ADM | General practice and psychiatric clinics | Doctoral level psychologist with experience in CBT | CBT reduced rates of recurrence but differences not significant in small sample |

| Behavioral: | |||||||||

| Nezu 1986[132] | Problem-solving therapy (PST) vs nonspecific therapy | 8 weekly 120-minute group sessions | Wait-list | Adult | 32 assigned of whom 26 completed | RDC MDD | Outpatient research clinic in university mental health center | Pre-doctoral graduate students in psychology | PST superior to either nonspecific or wait-list control |

| Nezu & Perri 1989[133] | Problem-solving therapy (PST) vs abbreviated PST | 10 weekly 90-minute group sessions | Wait-list | Adults aged 18-65 | 43 assigned of whom 39 completed | RDC MDD | Outpatient research clinic in university mental health center | Pre-doctoral graduate students in psychology | PST superior to either abbreviated PST or wait-list control |

| O'Leary & Beach 1990[138] | Behavioral marital therapy (BMT) vs cognitive therapy (CT) | 16 weekly sessions | Wait list | Adults aged 28-59 | 45 assigned of whom 45 completed | DSM-III MDD or dysthymia | Research clinic (recruited volunteers) | Pre- and post-doctoral clinical psychologists | BMT comparable to CT in reducing depression and both better than wait list; BMT better than CT or wait list on reducing marital distress |

| Beach & O'Leary 1992[139] | |||||||||

| Jacobson et al 1991[140] | Behavioral marital therapy (BMT) vs cognitive therapy (CT) vs combined treatment (BMT+CT) | 20 sessions over 12 weeks | None | Adults with mean age in high 30's | 72 assigned of whom 60 completed | DSM-III MDD | Research clinic (referrals and recruited volunteers) | Pre- and post-doctoral clinical psychologists and social worker | CT better than BMT for depression, whereas BMT better than CT for marital distress |

| Jacobson et al 1993[141] | |||||||||

| No differences between the groups across 12 months | |||||||||

| Arean et al 1993[134] | Problem-solving therapy (PST) vs reminiscence therapy (RT) | 12 weekly group sessions | Wait-list | Geriatric aged 55 and above | 75 assigned of whom 59 completed | RDC MDD | Outpatient research clinic in university medical center | Graduate students in clinical psychology | PST superior to RT and each superior to wait list |

| Mynors-Wallis et al 1995[135] | Problem-solving therapy (PST) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 6 30-minute sessions over 12 weeks (1st 60-minutes) | Pill-placebo (PLA) | Adults aged 18-65 | 91 assigned of whom 82 completed | Diagnostic method not specified | Primary care clinic | Psychiatrist and general practitioners (including authors) | PST or ADM superior to PLA |

| Van den Hout et al 1995[131] | Self-control therapy plus treatment-as-usual (SCT/TAU) | 12 weekly 90-minute group sessions | Treatment-as-usual (TAU) | Adults aged 20-59 | 49 assigned (number completed not reported) | DSM-III-R MDD or dysthymia | Psychiatric day-treatment center | Professional discipline not specified | Adding SCT enhanced response to TAU alone |

| Emanuels-Zuurveen & Emelkamp 1996[142] | Behavioral marital therapy (BMT) vs cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) | 16 weekly sessions | None | Adults with mean age in the high 30's | 36 assigned of whom 27 completed | DSM-III-R MDD | Outpatient research clinic in academic psychology department | Graduate students in clinical psychology | No differences between the conditions on depression with BMT having a greater impact on relationship variables |

| Jacobson et al 1996[144] | Behavioral component of cognitive therapy (bCT) vs partial cognitive therapy (pCT) vs full cognitive therapy (CT) | 20 sessions in 12 weeks | None | Adult with mean age in late 30's | 150 assigned of whom 137 completed | DSM-III-R MDD | Outpatient university clinic | Doctoral level clinical psychologists | No differences between different components in terms of reduction of acute distress |

| Gortner et al 1999[145] | |||||||||

| Prior CT vs prior pCT vs prior bCT | No differences with respect to prevention of subsequent relapse | ||||||||

| Dowrick et al 2000[137] | Problem-solving therapy (PST) vs depression prevention course (DPC) | 6 sessions (PST) and 8 sessions (DPC) | Assessment only control | Adults aged 18-65 | 425 assigned of whom 317 completed | DSM-IV MDD or Adj Disorder | Community settings | Health care professionals | Both PST and DPC superior to assessment only control |

| Mynors-Wallis et al 2000[136] | Problem-solving therapy (PST) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) vs combined treatment (PST/ADM) | 6 30-minute sessions over 12 weeks (1st 60-minutes) | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 151 assigned of whom 116 completed | RDC MDD | Primary care clinic | General practice physicians and research practice nurses | Combined treatment no more efficacious than PST or ADM (professional discipline of therapists made no difference) |

| Hopko et al., 2003[147] | Behavior activation (BA) vs nonspecific supportive psychotherapy (nSP) | 3 20-minute session per week for two weeks | None | Adults with a mean age of 30 | 25 assigned of whom 25 completed | Major Depression (unstructured psychiatric interviews) | Inpatient psychiatric hospital | Master-level clinicians | BA superior to nSP |

| Dimidjian et al 2006 (acute)[81] | Behavioral activation (BA) vs cognitive therapy (CT) vs antidepressant medication (ADM) | 20 sessions in 16 weeks | Pill-placebo (PLA) | Adults aged 18-60 | 241 of whom 172 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Doctoral level clinical psychologists and social worker (BA or CT) and research psychiatrists (ADM) | BA equals ADM and each better than CT or pill-placebo in reducing acute distress among more severe with no differences among less severe |

| Dobson et al 2008 (relapse)[98] | Prior BT or CT vs ADM continuation | Medication withdrawal onto pill-placebo | |||||||

| Prior BA equals prior CT or continued ADM with prior CT better than withdrawal onto pill-placebo in preventing relapse | |||||||||

| Bodenmann et al 2008[143] | Coping-oriented couples therapy (COCT) vs CBT vs IPT | 10 two-hour biweekly sessions (COCT) vs 20 weekly sessions | None | Adults aged 18 to 60 | 60 assigned of whom 57 completed | DSM-IV MDD (75%) and Dysthymia (25%) | Multisite trial with private practitioners in five Swiss cities | Experienced therapists | No differences between the groups with respect to depression or marital distress although COCT did produce greater change in partner's expressed emotion |

| Experiential-Humanistic: | |||||||||

| Beutler et al 1991[148] | Focused expressive psychotherapy (FEP) vs cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) | 20 weekly group sessions | Supportive self-directive control | Adults aged 22 to 76 | 63 of whom 42 completed | DSM-III MDD | Outpatient research clinic at university medical center | Experienced doctoral level psychologists | Modest main effects favored CBT but resistant patients did best in supportive self-directed control |

| Greenberg & Watson, 1998[149] | Process experiential therapy (PET) components added to client centered therapy (CCT) | 16-20 weekly sessions | None | Adults with a mean age of 40 | 34 of whom 33 completed | DSM-III-R MDD | Outpatient clinic in academic department | Psychiatrist, doctoral psychologists, and graduate students in psychology | No differences between the conditions on measures of depression but PET superior to CCT on measures of interpersonal problems and self-esteem |

| Watson et al 2003[150] | Process experiential therapy (PET) vs cognitive therapy (CT) | 16 sessions over 16 weeks | None | Adults with a mean age in the high 30's | 93 assigned of whom 66 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Outpatient clinic in academic department | Graduate students in counseling psychology and doctoral level psychologists | No differences between the conditions on measures of depression but PET superior to CT on self-reports of interpersonal problems |

| Castonguay et al 2004[153] | Integrative CT (with humanistic and interpersonal strategies) | 16 sessions over 12-15 weeks | Wait list | Adults aged 18-55 | 28 assigned of whom 22 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Outpatient research clinic in psychology department | Graduate students in psychology | ICT superior to wait list control |

| Goldman et al 2006[151] | Emotion-focused therapy (EFT) vs client-centered therapy (CCT) | 16-20 sessions over 16 weeks | None | Adults with mean age in late 30's | 83 assigned of whom 72 completed | DSM-III-R MDD | Outpatient clinic in academic department | EFT superior to CCT | |

| Ellison et al 2009[152] | Responders to EFT less likely to relapse over subsequent 18 months than CCT responders | ||||||||

| Constantino et al 2008[154] | Integrative CT (with humanistic and interpersonal strategies) vs CT alone | 16 sessions over 13-16 weeks | None | Adults aged 18-65 | 22 assigned of whom 19 completed | DSM-IV MDD | Outpatient research clinic in university medical center | Graduate students in psychology | ICT superior to CT |

| Marital and Family: | |||||||||

| Freidman 1975[155] | Dynamic marital therapy vs antidepressant medication (ADM) vs combined treatment | 12 weekly sessions | Pill-placebo | Adults aged 21-67 | 196 assigned of whom 168 completed | Primary diagnosis of depression | Outpatient research clinic | Professional discipline unspecified | ADM better at reducing depression and dynamic marital therapy better at reducing marital distress; combined treatment retained specific benefits of each |

| Clarkin et al 1990[156] | Family therapy plus milieu therapy with antidepressant medication | 6 family sessions in 36 days | Milieu therapy with antidepressant medication | Adults with mean age in mid-30's | 56 assigned of whom 50 completed | DSM-III MDD (n=30) or BD (n=26) | Inpatient research setting at university medical center | Social workers | Female bipolar patients benefited from addition of family therapy but not unipolar patients |

Dynamic Psychotherapy

The dynamic psychotherapies represent the oldest treatments for depression. Early findings were generally unimpressive, although the approach was often included as a comparator by investigators with other allegiances. For example, McLean and Hakstian found brief dynamic therapy less efficacious than their preferred behavioral intervention or medications[14] and Covi and colleagues found dynamic group psychotherapy no better than placebo and less efficacious than medications in one study[15] and less efficacious than CBT (with or without medications) in another.[16] No differences were found relative to social-skills training[17] or self-control therapy[18] in a pair of studies implemented by behaviorally-oriented researchers and few differences were found between psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy and CBT in a pair of studies by investigators with little expertise with CBT.[19,20]

Recent studies by investigators with expertise in dynamic psychotherapy have been somewhat more supportive but still less than wholly compelling. A study by Cooper and colleagues in England found that psychodynamic psychotherapy did not differ from CBT or non-directive counseling and that each produced greater change on measures of depression than did routine primary care in the treatment of postpartum depression.[21] A study by Burnand and colleagues in Switzerland found that adding dynamic psychotherapy to medication reduced the proportion of patients who met criteria for MDD following treatment and led to better work adjustment, although there were no differences on measures of depressive symptoms.[22] A study by Salminen and colleagues in Finland on patients with mild-to-moderate MDD in a general practice setting found no differences between short-term dynamic psychotherapy versus fluoxetine antidepressant medication, but the sample was too small to draw firm conclusions.[23] De Jonghe and colleagues in the Netherlands found that adding short-term dynamic psychotherapy increased the proportion of patients responding to medications by virtue of reducing rates of attrition[24] and that patients with personality disorders may have been more likely to respond to combined treatment than to medications alone.[25] A subsequent study by this same group found that antidepressant medications worked more rapidly than short-term dynamic psychotherapy and were superior after eight weeks of treatment.[26] Maina and colleagues in Italy found that brief dynamic therapy was no more efficacious than brief supportive psychotherapy when added to medications at the end of treatment, but that patients continued to improve over a subsequent six-month continuation phase[27] and that patients previously treated with dynamic psychotherapy were less likely to experience a recurrence over a subsequent 48-month treatment-free follow-up.[28]

One of these studies found clear evidence of efficacy relative to routine care[21] and adding psychodynamic psychotherapy enhanced the efficacy of medication on at least some measures in a second,[22] and for at least some patients in a third.[24,25] This is better than it had done in those earlier trials. Perhaps most interesting were the indications that patients treated with brief dynamic psychotherapy plus medications continued to improve after the end of active treatment[27] and were less likely to recur than patients previously treated with supportive psychotherapy plus medications.[28] At the same time, none of these studies found dynamic psychotherapy superior to a nonspecific control or alternative treatment; results were more promising than early trials but hardly impressive.

Dynamic psychotherapy has rarely been tested in the treatment of geriatric depression, but the samples studied have been so small and the quality of the alternative interventions suspect; it is not clear that anything but null findings would have been expected. Gallagher and Thompson found few differences between brief dynamic therapy and either CBT or BT,[29] findings replicated in a second study in which all three active treatments pooled were superior to a wait list control.[30] Treatment gains produced by either CBT or BT were better maintained than those produced by dynamic therapy in the first study but not in the second.[31] A third study by this group found that short-term caregivers did better in brief psychodynamic psychotherapy than they did in CBT, whereas long-term caregivers showed the opposite pattern.[32] Conversely, Steuer and colleagues found CBT superior to dynamic psychotherapy delivered in a groups.[33] There is simply little in this literature to warrant a designation of efficacious or specific.

On the whole, although there is still not compelling evidence speaking to the efficacy of dynamic psychotherapy, it would be premature to conclude that it is not efficacious solely on the basis of early trials by advocates of other approaches. More recent studies by investigators who have an investment in and expertise with the approach do offer some limited support and meta-analyses that aggregate across studies regardless of quality find it no less efficacious than alternative types of psychotherapies.10,11 Although none of the studies in the literature provide strong support for the approach relative to either medications or alternative psychotherapies, one study does suggest an advantage over routine primary care[21] and two others suggest that it can enhance the efficacy of medications on at least some measures[22] and for at least some patients.[24,25] Yet another recent study suggests that its effect may build over time[27] and protect against subsequent recurrence.[28] It seems fair to say that dynamic psychotherapy is possibly efficacious with respect to acute response and the prevention of subsequent relapse/recurrence.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) springs from dynamic roots, but draws on attachment theory and theoretical revisions that focus on interpersonal relationships.[34] It is more structured than dynamic psychotherapy (but less so than cognitive or behavioral approaches) and focuses on current interpersonal difficulties rather than childhood recollections or the therapeutic relationship.[35]

IPT has fared well in a series of controlled trials in fully clinical populations. Klerman and colleagues found that patients treated to remission with the combination of IPT and medications were no more likely to relapse if continued on IPT alone than if continued on medications[36] and patients treated with IPT showed a greater (if somewhat delayed) improvement in interpersonal functioning than did patients treated with medications alone.[37] In a subsequent study, Weissman and colleagues found that outpatients treated with IPT did as well as patients treated with medications and better than patients provided with treatment-on-demand in terms of symptom reduction and that patients treated with combined treatment did better still.[38] Drugs produced more rapid change,[39] but IPT again had a delayed effect on interpersonal functioning.[40] This study speaks to the efficacy of IPT in the reduction of acute symptoms.

IPT also fared well in the placebo-controlled NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Project (TDCRP), one of the largest and most influential studies of its time.[41] Among more severely depressed patients, both IPT and drugs outperformed pill-placebo, whereas CBT did not; no differences were evident among less severely depressed patients or in the sample as a whole.[42] Once again, drugs produced faster change than IPT, which showed more change later in treatment.[43] IPT also reduced depressive symptoms and improved social adjustment in women suffering from postpartum depression over wait list in one study[44] and was superior to didactic parent education in a sample of pregnant women with MDD in another.[45] This last study and the TDCRP suggest that IPT is efficacious and specific in the treatment of MDD.

Subsequent studies have not been as supportive. A study conducted in New Zealand found that IPT was less efficacious than CT for patients with more severe depression[46] or perhaps personality disorders.[47] Similarly, a recent Canadian trial found IPT less efficacious than medications.[48] Internal analyses indicated that IPT did particularly poorly with patients high on self-criticism. Although efficacious and specific according to Chambless and Hollon's (1998) criteria,[7] findings with respect to IPT are no longer as consistent as they once were when only advocates conducted trials on the approach.

Studies in special populations also are worthy of note. IPT was as efficacious as drugs (imipramine) plus supportive therapy and more efficacious than either CT or supportive psychotherapy alone in the treatment of depression in a sample of HIV-positive patients; this study would speak to both efficacy and specificity except that only about half the sample met criteria for MDD.[49] Bolton and colleagues found that indigenous nonprofessionals in rural Uganda could be trained to provide group IPT to fellow villagers that reduced rates of depression and improved functioning[50] and that these differences were sustained across a six month follow-up.[51] IPT was as efficacious as medications (if somewhat slower acting) and more efficacious than treatment-as-usual in one study in a primary care setting,[52] although training physicians to provide IPT-based education did little to enhance response to medication in a small general practice sample in another.[53] Adding IPT enhanced response to medication in an inpatient sample,[54] including patients with chronic depression,[55] and there were indications that these differences extended beyond the end of treatment. Finally, a version of the approach adapted for depressed mothers of offspring with psychiatric disorders (IPT-MOMS) was more efficacious than treatment-as-usual in reducing depression in both the mothers and their offspring.[56] On the other hand, Reynolds and colleagues found that IPT did not differ from pill-placebo and was less efficacious than medication in reducing acute distress in a “young” geriatric sample (aged 50 and above) with a history of recent bereavement[57] and no better than usual care with respect to rates of remission or measures of symptom change in another study on a geriatric primary care sample aged 55 and over, although it did reduce the proportion of patients who continued to meet criteria for depression at posttreatment.[58]

Frank and colleagues found monthly maintenance IPT superior to withdrawal onto pill-placebo in a sample of recurrent patients treated to recovery with combined treatment, but maintenance medication (imipramine) was more efficacious still and combined treatment did nothing to improve on medications alone.[59] Maintenance IPT was most efficacious when the sessions maintained a high level of interpersonal focus suggesting the importance of quality of implementation.[60] When this design was replicated in that same setting in a “young” geriatric sample (mainly 60 to 75 years of age), both maintenance IPT and maintenance medications were superior to pill-placebo, with combined treatment best of all.[61] These studies suggest that maintenance IPT is possibly efficacious for the prevention of recurrence, although a subsequent replication found maintenance IPT no more efficacious than pill-placebo and less efficacious than maintenance medication in the treatment of depression in an older geriatric sample aged 70 and above.[62] IPT was protective of cognitively impaired unmedicated elders.[63]

Although negative findings do exist,[46-48] IPT appears to be efficacious and specific in the reduction of acute distress[42,45] and may forestall both relapse and recurrence so long as it is continued or maintained, although perhaps not so well as medications.[36,59,61] In some studies, combined treatment improved on drugs alone,[38,54] although that was not always the case. There also were indications that IPT has a delayed effect on interpersonal skills and relationship quality that builds over time.[37,40] This represents a specific benefit of IPT and may enhance its value as an adjunct to medications. It also appears to be efficacious in the treatment of perinatal depression.[44,45] This is important since pregnant and lactating women may have special reasons to prefer not to be on medication. Recent trials by investigators outside of the core IPT group have not been as uniformly supportive as earlier trials by advocates for the intervention, but the efficacy of the approach appears to be well established when implemented by well-trained therapists.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

The cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT), of which cognitive therapy (CT) is the most widely practiced variant, assume that negative beliefs and maladaptive information processing contribute to the onset and maintenance of depression. These interventions seek to produce change by teaching patients to evaluate the accuracy of their beliefs (or the relation between their thoughts and feelings in the newer meditation-based approaches), often by using their own behaviors to test their beliefs. CBT has been tested extensively and typically found to be superior to minimal treatment controls and at least as efficacious as other empirically supported interventions.[64] Nonetheless, questions remain as to how it compares to drugs in the treatment of severe depression.[65]

Early studies suggested that CT might be superior to drugs, but often implemented medications in a less than adequate fashion.[66,67] The same appeared to be the case in a later trial that found both CT and relaxation training (included as a nonspecific control) superior to tricyclic ADM in a very small sample with an uncharacteristically poor response to medication.[68] These studies could be taken as support for the specific efficacy of CT since even inadequately implemented medication conditions should have controlled for nonspecific factors, but we are not prepared to go so far. Subsequent studies suggested that CT and drugs are comparable in efficacy when each is adequately implemented[69,70] and an even more recent study suggests that the same may be true for rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT),[71] with either type of psychotherapy more cost-effective.[72] As previously described, CT was less efficacious than either IPT or medications and no more efficacious than pill-placebo in the treatment of severe depression in the TDCRP, the largest and best controlled study of its time,[41,42] but response to treatment varied across sites and CT did as well as medication in the site with more experienced cognitive therapists.[73] DeRubeis and colleagues reanalyzed individual response data on severely depressed patients from the studies just cited and found no differences between CT and drugs across the pooled samples.[74] However, we are reluctant to base a claim of efficacy solely on equivalence to an established standard.[7]

A more recent trial by Jarrett and colleagues found CT as efficacious as medications and superior to pill-placebo in patients with atypical depression[75] and a subsequent study by DeRubeis and colleagues essentially replicated these findings among patients with more severe depressions.[76] These trials are important because they demonstrate that CT can do as well as medications in fully clinical samples that respond to medications.[77] The fact that CT was superior to pill-placebo in each speaks to both efficacy and specificity. An even more recent trial from Iran found CBT superior to medications and both superior to a no treatment control in a sample of depressed women with fertility problems.[78]

However, the efficacy of CT may be moderated both by patient characteristics and therapist experience. In the study by DeRubeis and colleagues,[76] patients with Axis II disorders did better on medications than they did in CT, whereas patients free from such disorders showed the opposite pattern.[79] Moreover, CT was less efficacious than medications at the site with less experienced cognitive therapists[76] (see also the study by Bright and colleagues).[80] This is reminiscent of earlier findings from the TDCRP and consistent with the poor showing by somewhat less experienced cognitive therapists with more severe and complicated patients in a placebo-controlled comparison to medication or behavioral activation described in a subsequent section.[81] Similarly, Bagby and colleagues found that patients with higher neuroticism scores did better on medications than they did in CBT in a study that otherwise found no main effect for treatment.[82] On the other hand, a recent trial from New Zealand found that CT was more efficacious than IPT among patients with more severe depression[46] or Axis II disorders.[47] Although the therapists in that trial were all experienced, it is not clear just how expert they were with either treatment. These findings suggest that CT's efficacy with more severe and complicated patients may vary across studies and depend in part on therapist experience.

Another recent study found CT as efficacious as drugs in recurrent patients[83] and adding CT typically enhanced the efficacy of medication treatment in inpatient samples.[84,85] Studies in primary care settings have found that adding CT typically enhances the efficacy of usual care[86,87] and did so in one study over and above the benefits provided by a contact control,[88] although that has not always been the case.[89] CT was as efficacious as medications and superior to community referral in a sample of mostly low-income minority women with MDD[90] and its effects extended across a one-year follow-up.[91] CBT was superior to treatment-as-usual (TAU) among severely depressed outpatients.[92] In general, these findings are consistent with the notion that CBT is efficacious (if not necessarily specific) in the treatment of MDD.

Patients treated to remission with CT are less likely to relapse following treatment termination than patients treated to remission with drugs alone;[93-95] the magnitude of this effect is at least as great as keeping patients on continuation medication[96] and superior to placebo withdrawal.[97,98] Only the TDCRP failed to find an enduring effect for prior CT.[99] Moreover, these effects may extend to the prevention of recurrence, although comparisons to placebo controls typically do not extend beyond the period of risk for relapse.[97,98] These studies indicate that CT has an enduring effect that is both efficacious and specific in the prevention of relapse and efficacious with respect to recurrence.

Studies also have shown that CBT can be added following initial medication treatment to prevent subsequent symptom return and that this enduring effect can last for up to several years.[100-103] Providing group CBT to remitted patients reduced risk for subsequent relapse or recurrence among patients with more prior episodes[104] and a similar moderated effect was found for acute CBT followed by brief psychoeducation (but not psychoeducation alone) for patients with four or more prior episodes.[105] An earlier trial by this latter group found no differences between a depression recurrence prevention program with or without CBT relative to usual care in a general practice sample.[106] The only studies that failed to find an enduring effect for CBT provided following remission compared it to continuation medication.[107,108]